面对柴油门事件,大众在欧美的待遇为何如此悬殊|深度报道

本文由《财富》与非盈利调查新闻机构ProPublica共同撰写。

|

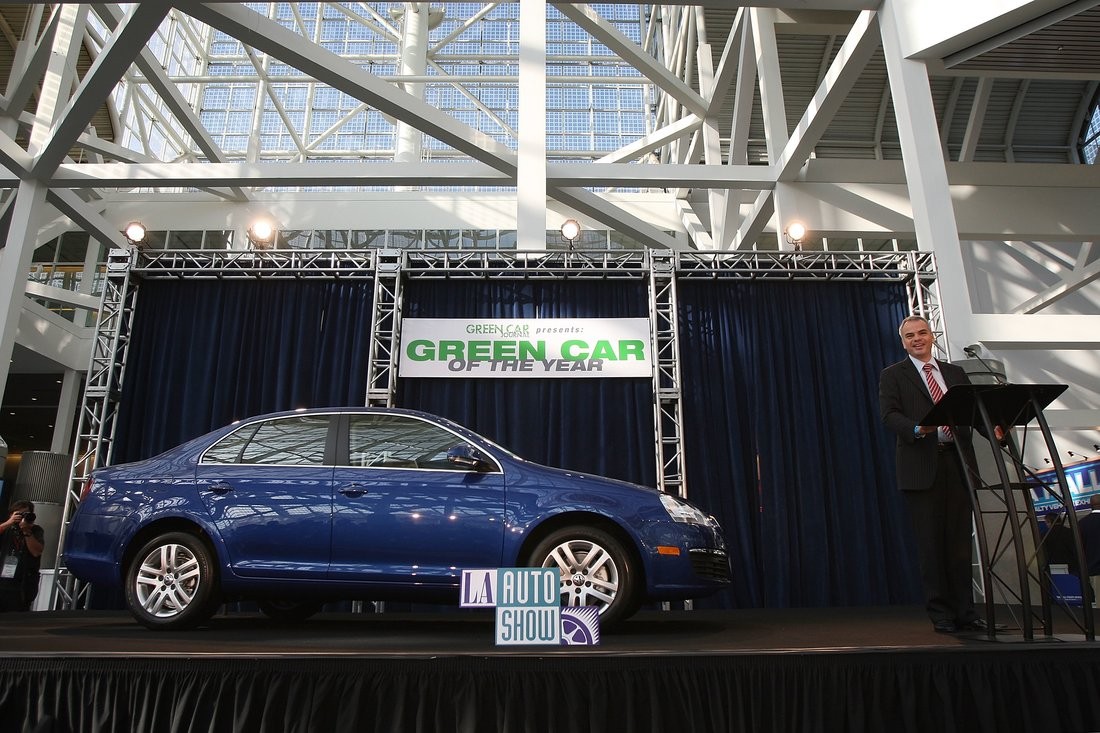

12月6日,带着手铐和脚链的前大众工程师奥利弗·施密特被带到了底特律联邦法院。他穿着一件血红色的套头衫,与往常一样剃着光头,他深陷的双眼似乎在问,我为什么会落到这个地步?就在坐在第二排的施密特妻子强忍着不让眼泪流下来时,美国地方法官肖恩·科克斯宣布判处施密特7年监禁,如果放在施密特的祖国德国,这将是有史以来最为严厉的白领犯罪判罚之一。 施密特因其在大众“柴油门”丑闻而受到惩罚,该丑闻是历史上最明目张胆的企业欺诈之一。然而他的宣判并没有什么净化作用,在科克斯法官看来尤为如此,他有时对做出这一判决感到很痛苦。他对施密特怀有歉意地说道,有时候,他的工作要求他监禁那些“犯有重大决策错误的好人”。 所有人都知道,施密特只是一个从犯,而他的判决只是帮某人顶罪而已。科克斯法官此言针对的是德国的某些人,他们超出了美国检察官的审查权限,因为德国通常不会将其公民引渡至欧盟境外的地方受审。最为重要的是,底特律法院也因马丁·文德恩这位幕后人的缺席而感到困扰。这位大众首席执行官的任职期限贯穿欺诈事件的始末。虽然他的名字在法庭上仅提到过两次,但他的阴云却始终笼罩着整个听证会。 丑闻的大概内容大家都很清楚。在近10年的时间中,从2006年-2015年9月,大众确定了其一系列车型的美国销售策略,旨在让公司超越对手丰田,成为全球排名第一的汽车制造商,结果却成了一场骗局。这些车被冠以“清洁柴油”车型的美名。公司大众、奥迪和保时捷品牌在美国共销售了约58万辆这类轿车、SUV和跨界车。借助铺天盖地的宣传攻势,包括超级碗广告,大众营造了一个环保主义梦想:自家的车辆既有高性能,也具备出色的油耗和排放指标,它是如此之环保,完全可以与丰田普锐斯这类混合动力车相媲美。 但这只不过是由软件构筑的泡影罢了。根据设置,大众柴油车的尾气控制设备会在车辆脱离监管方测试台时自动关闭,此时,排气管会向大气中排放两种超过法定浓度的两种氮氧化合物(统称NOx),可引发雾霾、呼吸道疾病和夭折。 最初,大众坚决认为造假行为源于公司的一群素质低劣的工程师。但一段时间之后,公司不动声色地放弃了这一主张,转而专注于保护一小部分高管。这一犯罪行为最初的情形可能是:少数工程师害怕向焦虑的高管承认,自己已经无法在实现公司目标的同时满足法律的要求。 在过去两年中,美国和德国检方一直都在追踪那些知晓这一密谋的人士,而且已经查出了40多名涉案人员,这些人员至少来自于4个城市,分属于三个大众品牌以及汽车技术供应商罗伯特博世。一些司法部门的官员正试图推行一项可能具有轰动效应的新举措,即起诉大众前任首席执行官。然而,这类举措基本上没有什么实质性的意义,因为美国与德国之间没有达成引渡协议,但它会释放这样一个信号:这一欺诈行为的性质十分恶劣,而且源自于大众的高层。 同时,它也会凸显两个不同地区在惩罚方面的巨大反差。美国当局对大众在美销售的58万辆造假柴油车做出的罚款、处罚和赔偿共计达到了250亿美元。在欧洲,虽然大众销售了800万辆问题柴油车,但却没有收到任何国家的政府所开出的罚单。 毫无疑问,奥利弗·施密特是有罪的。他承认参与了事实真相的掩盖。然而,他与幕后主谋还有很大的差距。施密特声称,自己直到2015年6月才知晓软件作弊一事,然而3个月后,这一长达十年的阴谋便画上了句号。不过,他承认自己曾在2013年“怀疑”过此事。 48岁的施密特多年来一直是大众与美国环保当局的主要联系人。他最近才升迁公司的中层管理人员(年薪约17万美金),也就是在这个时候参与了真相的掩盖。他的一切都说明他将成为一位与车打交道的商人。他出生于大众占主导地位的下萨克森州,大众60万名员工当中有11万在那里工作。施密特于1997年退伍之后便直接加入了大众。其律师向法官转交了50封私人信件,这些信件都将其描述为一位忠诚、关爱他人的儿子、兄弟、丈夫、叔叔和朋友。科克斯法官表示,“我从来没有看到过这么多的证明信。”据信中描述,他在业余时间喜欢收集以前的轨道赛车套装,并重新组装经典的大众甲壳虫。在施密特2010年结婚时,他和妻子(妻子是一名汽车工程师)在朋友迈阿密的大众经销店展示厅中举行了婚礼。施密特是一位异常忠诚的人,一生都献给了大众。 科克斯法官在听证会上解释说,施密特的判决旨在进一步加强“一般性威慑力”。换句话说来说,其目的在于给其他的企业高管提个醒:听从非法的命令不能作为开脱的理由。显然,这一判决也体现了法官的无奈。 施密特承认自己有罪,科克斯法官对他说,“这一判决是为了震慑高管和董事会”。科克斯指的是文德恩,后者不仅在2007年便开始担任首席执行官(直到2015年才因丑闻辞职),同时还是公司管理委员会的主席。施密特律师和检察官认可的众多证据显示,施密特和另一名员工曾在2015年7月27日向文德恩和其他高管做过汇报。 文德恩是一位臭名昭著的微观管理者。他因携带测微计而出名,这样,他便可以按照百分之一毫米的精确度来测量大众的零部件和公差。同时,他在执行纪律方面达到了专横无理的地步。当时,他也是德国薪资最高的首席执行官,去年的收入达到了1860万美元,是施密特的100倍。 施密特和一名同事被叫到文德恩眼前,以帮助解决这一危机。美国监管当局已采取激进的举措,禁止销售大众2016年柴油车车型。由于这一举措对于公司的美国战略有着至关重要的影响,这位首席执行官希望施密特解释到底都发生了什么事情。施密特回答道,加州空气资源委员会和美国环保局发现了一个严重的异常情况:大众的清洁柴油车在实验室中符合NOx的排放标准,但一旦到了公路上,车辆尾气中NOx的浓度最高可超出法律上限40倍。出于对大众一年多以来回避问题和妨碍调查的不满,监管当局决定禁止销售大众2016年柴油车型,直到大众找到解决之道。 2015年7月与文德恩的会议对法律诉讼所称的不当行为进行了详细的分析。施密特的判决备忘录写道,“一名未遭到指控的同谋提供了有关作弊装置的一些技术信息。”(“作弊装置”一词指的是让大众柴油车在排放测试中作弊的软件。)施密特曾警告与会人员,“如果监管当局发现了这一作弊行为,可能会给公司带来严重的后果”。在FBI探员向施密特发起诉讼的书面陈述中写道,施密特在其演示中的一页幻灯片中提到了这一令人不安的可能后果——“指控?” 检察官本杰明·辛格在判决时对科克斯法官说,施密特和其同事以准确无误的语言向参会人员解释了大众一直在作弊以及公司如何作弊。(检察官和施密特的律师大卫·杜莫切尔拒绝接受采访。) 如果人们相信检察官和施密特在说真话,也就是文德恩在会面时确实得知了大众作弊的信息,那么这位首席执行官所采取的后续行动看起来有欲盖弥彰的嫌疑。文德恩并未下令通知当局有关大众作弊的事情,或发起调查以弄清事实真相。 反而,他交给了施密特一个任务:劝说美国监管方允许销售大众2016年柴油车型。 施密特的判决备忘录写道,文德恩“授命施密特先生与他在美国期间结识的加州空气资源委员会高级别官员进行非正式会面。”FBI探员在其书面陈述中写道,“大众高管并没有建议向美国监管方披露作弊装置,而是授权继续隐瞒真相。”。 施密特的备忘录称,在出发前往美国之前,施密特就“与加州空气资源委员会会面期间打算使用的说辞征求了意见并获得批准”。备忘录中写道,这一说辞至少得到了文德恩以下四名高管的批准,而且“施密特先生得到指示,不得向美国方面透露作弊装置的信息或存在任何有意的作弊行为。” 2015年8月,施密特从德国飞到密歇根,并用谎言连续蒙骗了两名加州空气资源委员会官员。他通过邮件向德国老板和其他10名“高级别人员”汇报了“进展详情”,并表示“他一直都在使用——按照施密特自己的话来说——大众所选择的谎言和骗术。”,检察官辛格说道。 最终,另一名已无法容忍这种欺骗行径的大众工程师抛弃了这些说辞,并于8月19日的一次会面中向加州空气资源委员会交代了事实真相。大众的一名总监于9月3日正式向监管方承认使用了作弊装置,随后,美国环保局和加州空气资源委员会迫使大众于2015年9月18日向公众披露了真相。 文德恩于5日后离任,称自己对“过去几天”所发生的事情感到“震惊”,并表示他“本人对这些不当行为一无所知。”公司监事委员会同一日宣布其没有过错,并称文德恩“对于操纵排放数据一事毫不知情。”在2017年1月的德国国会听证会上,文德恩坚决表示,自己在丑闻公之于众之前从未听说过“作弊装置”一词。他在当天的四个场合中曾拒绝回答议员的问题,理由是德国检方正在对其进行刑事调查。 到目前为止,施密特在底特律的判决是这位前首席执行官与美国刑事司法距离最近的一次接触。在这一阴谋曝光27个月之后,文德恩仍未在美国或德国受到任何罪名指控。(他的美国律师拒绝就此文置评) 他以后会吗?是否会有比施密特位置更高的高管来承担这一重罪? 这些问题的答案仍不甚明朗。据两名知情人士透露,虽然美国检方希望起诉文德恩,但并未收到司法部高官的批准。 这看起来似乎是迈出了巨大的一步。然而事实在于,在美国对文德恩或其他大众高管的起诉正在逐渐失去其实际意义,原因很简单,检方无法接触到本案的大多数关键人物。文德恩自丑闻爆发之后就再未踏入美国一步,而且在施密特获得重刑之后,他也不大可能在近期前往美国。 在美国受到指控的8名工程师中,只有施密特和詹姆士·梁(这名非总监级人员在去年8月被判处40个月的监禁),而实际上在美国,只有一名人员——奥迪引擎开发总监扎切欧·帕米欧——恰好是一名可以引渡的意大利籍人士。 这意味着司法焦点将转移至德国。在那里,的确有三组检方正在酝酿开展合适的行动。 代表下萨克森州(母公司VW AG和其大众品牌乘用车部门总部所在地)的布伦瑞克当局表示,他们正在就与柴油门相关的造假案件调查39名人士,其中一名涉嫌阻碍司法调查,三明涉嫌金融市场操控(在这一案件中意味着未能及时向股东披露这一即将爆发的危机)。在慕尼黑,巴伐利亚检方正在调查大众奥迪部门(总部位于英戈尔施塔特)13名人士,他们涉嫌欺诈和虚假广告。在斯图加特,三名高管因涉嫌市场操控而正在接受调查。 两次市场操纵调查主要针对文德恩和三名大众现任资深高管。例如,布伦瑞克检方正在调查监管理事会董事长汉斯·珀奇(在丑闻爆发之前担任首席财务官)以及现任大众品牌经理赫伯特·戴斯,而斯图加特当局在调查珀奇和现任首席执行官马希尔斯·穆勒。(大众拒绝就本文公开置评,而是提供了一份书面声明,并声称其高管完全遵守披露法。) 然而,调查的进展异常缓慢。目前仅有两名德国人被逮捕。一位是帕米欧,另一位是沃尔夫冈·哈茨,曾先后担任奥迪、大众和保时捷的高级主管。德国检方并未确认已扣留个人的身份以及指控罪名,但该办公室称,慕尼黑检方的关注点在于欺诈和虚假广告。 在德国,刑事诉讼并不多见,定罪或长期监禁就更少见了。该国的法律设置了很多巨大的障碍。首先,公司不存在刑事责任。没有法律禁止犯罪预谋,没有相关的清洁空气刑法,也没有针对欺骗监管方或调查人员的法律。(柏林自由大学法学教授卡斯滕·孟森称,后者实际上受到德国沉默权强有力的保护。)检方奖励和将犯罪者转化为公诉方证人的手段要弱于其同僚美国检方,而且即便刑法的部分内容有这方面的规定——可逮捕欺骗其他人的个人,但也不适用于本案中所出现的企业密谋。 这两个国家的公司和其客户所面临的结果是迥然不同的。在美国,司法体系很快给出了结果。在严厉的企业刑事制裁、灵活严苛的刑法和精简的消费者集体诉讼程序面前,大众很快低下了头。在9个月内(法律界的超高速),大众同意就涉案的2.0排量轿车向消费者以及联邦和州相关部门支付约150亿美元的民事赔偿和补偿,而且随着该案件的涉及范围扩大至3.0排量的车辆,再加上刑事罚款和处罚,总金额已蹿升至250多亿美元。大众已经回购和修理了大部分涉案车辆,而且客户也因此获得了每辆车数千美元的赔偿,用于弥补其各类损失,包括欺骗和转售价值的降低。面对阴谋、欺诈、制造虚假声明和妨碍司法的联邦刑事诉讼,大众于4月承认有罪。 大众委托Jones Day律师事务所开展了一项调查,涉及700多个采访,并搜集了1亿多份文件,大众为美国检方提供了随意获取这一调查结果的权限。(大众称,这一调查仍在开展当中。)大众还帮助恢复了供法庭使用的数千页的文件,这些文件在阴谋泄漏前夕被众多大众雇员所删除。作为交换,美国检方对大众的配合表示首肯,免去了20%的刑事罚金,但即便在减少之后,这一数字依然高达28亿美元。 在加拿大,公司也支付了赔偿,包括针对1月份刚刚抵达的3.0升车辆所支付的2.9亿美元。在韩国,大众也付出了惨痛的代价,公司不仅支付了天额罚金,其当地的大众和奥迪官员也遭到了刑事诉讼,其中一名被判处18个月监禁,如今正在服刑。 然而在德国和欧洲,事情却完全不一样。大众没有向任何客户支付赔偿。在公司的决策之地以及决策者所在地德国,大众没有受到任何刑事或行政罚款或处罚。 |

On Dec. 6, former Volkswagen engineer Oliver Schmidt was led into a federal courtroom in Detroit in handcuffs and leg irons. He was wearing a blood-red jumpsuit, his head shaved, as it always is, and his deep-set eyes seemed to ask, how did I get here? As Schmidt’s wife tried to suppress tears in a second-row pew, U.S. District Judge Sean Cox sentenced him to what, had it been imposed in Schmidt’s native Germany, would rank among the harshest white-collar sentences ever meted out: seven years in prison. Schmidt was being punished for his role in VW’s “Dieselgate” scandal, one of the most audacious corporate frauds in history. Yet his sentence brought no catharsis, least of all to Judge Cox, who at times seemed pained while imposing it. Sometimes, he told Schmidt apologetically, his job requires him to imprison “good people just making very, very bad decisions.” Schmidt was a henchman, everyone understood, and his sentence, a stand-in. Judge Cox was addressing a set of people in Germany who are beyond the reach of U.S. prosecutors because Germany does not ordinarily extradite its nationals beyond European Union frontiers. Above all, the Detroit courtroom was haunted by the shadow of an individual who was absent: Martin Winterkorn, who was VW’s CEO during almost all of the fraud. His name was uttered only twice, yet his aura loomed over the entire hearing. The outlines of the scandal are well known. For nearly a decade, from 2006 to September 2015, Volkswagen anchored its U.S. sales strategy — aimed at vaulting the company past Toyota to become the world’s number one carmaker — on a breed of cars that turned out to be a hoax. They were touted as “Clean Diesel” vehicles. About 580,000 such sedans, SUVs, and crossovers were sold in the U.S. under the company’s VW, Audi, and Porsche marques. With great fanfare, including Super Bowl commercials, the company flacked an environmentalist’s dream: high performance cars that managed to achieve excellent fuel economy and emissions so squeaky clean as to rival those of electric hybrids like the Toyota Prius. It was all a software-conjured mirage. The exhaust control equipment in the VW diesels was programmed to shut off as soon as the cars rolled off the regulators’ test beds, at which point the tail pipes spewed illegal levels of two types of nitrogen oxides (referred to collectively as NOx) into the atmosphere, causing smog, respiratory disease, and premature death. At first, Volkswagen insisted the fraud was pulled off by a group of rogue engineers. But over time the company has quietly backed away from that claim, increasingly focusing on protecting a small cadre of top officials. The crime may well have started among a relatively small number of engineers afraid to admit to feared top executives that they couldn’t reconcile the company’s goals and the law’s demands. Over the past two years, prosecutors in the United States and Germany have been tracing who was aware of the scheme and have identified more than 40 people involved, spread out across at least four cities and working for three VW brands as well as automotive technology supplier Robert Bosch. In a new, potentially explosive move, some Justice Department officials are pushing to indict Volkswagen’s former CEO. Such a step would be largely symbolic — the U.S. has no extradition treaty with Germany — but it would send a message that the misconduct was egregious and directed from the top. And it would highlight a stark contrast in punishment. U.S. authorities have extracted $25 billion in fines, penalties and restitution from VW for the 580,000 tainted diesels it sold in the U.S. In Europe, where the company sold 8 million tainted diesels, VW has not paid a single Euro in government penalties. There’s no doubt that Oliver Schmidt was guilty. He admitted that he’d been part of a cover-up. Yet he was far from the mastermind. Schmidt claimed not to have learned of the cheating till June 2015, just three months before the decade-long conspiracy ended, though he admitted that he “suspected” it in 2013. Schmidt, 48, was an engineer who for several years was VW’s main point of contact with U.S. environmental regulators. He had only recently been promoted to a midlevel officer (making about $170,000 a year) when he got involved in the cover-up. Everything about him exuded a car-oriented company man. Born in Lower Saxony, the VW-dominated state where about 110,000 of the company’s 600,000 employees work, Schmidt came to the company in 1997, straight out of military service. About 50 personal letters submitted through his attorney — “I don’t think I’ve ever seen as many,” Judge Cox observed — extolled him as a loyal and loving son, brother, husband, uncle, and friend. In his spare time, the letters recounted, Schmidt enjoyed collecting old slot-car racing sets and restoring classic VW Beetles. When Schmidt got married, in 2010, he and his wife (herself an automotive engineer) held the ceremony in the showroom of a friend’s Volkswagen dealership in Miami. Schmidt was an all-too-loyal, VW lifer. His punishment was designed to further “general deterrence,” Judge Cox explained at the hearing. In other words, the point was to send a message to other corporate officials that following illegal orders is no defense. It doubtless reflected frustration as well. Schmidt had committed his crime, Judge Cox told him, “to impress … senior management and the board.” He was talking about Winterkorn, who was not only CEO from 2007 till the scandal brought him down in 2015, but also chairman of the company’s management board. Schmidt and a second employee had made presentations to Winterkorn and other senior officials at a meeting on July 27, 2015, according to versions of the facts endorsed by both Schmidt’s counsel and the prosecutors. Winterkorn was a notorious micromanager — he was known for carrying a micrometer with him, so he could personally measure VW parts and tolerances down to the hundredth of a millimeter — and an imperious martinet. He was also then the highest paid CEO in Germany, having made $18.6 million the previous year, more than 100 times Schmidt’s pay. Schmidt and a colleague had been summoned before Winterkorn to help solve a crisis. U.S. regulators had taken the drastic action of refusing to permit the sale of VW’s model year 2016 diesels — so crucial to its U.S. strategy — and the CEO wanted Schmidt to explain what was going on. As Schmidt would lay out, regulators with the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had discovered a serious anomaly: VW Clean Diesels complied with NOx-emissions standards when tested in the lab, but then discharged up to 40 times the legal limit when driven on a road. Dissatisfied with more than a year of evasions and stonewalling, the regulators had decided to bar VW’s 2016 diesels from the U.S. until they got better answers. The July 2015 meeting with Winterkorn delved into detail about the company’s misbehavior, legal filings allege. “An unindicted co-conspirator presented certain technical aspects of the defeat device,” according to Schmidt’s sentencing memo. (“Defeat device” is the phrase used to describe the software that enabled VW diesels to fool emissions tests.) Schmidt warned attendees of “the potential severe consequences to VW if regulators discovered the cheating.” A slide in his presentation raised a disturbing prospect — “Indictment?” — according to the FBI agent’s affidavit that initiated the charges against Schmidt. Schmidt and his colleague explained to the group “in unmistakable terms that Volkswagen had been cheating, how they were cheating,” prosecutor Benjamin Singer told Judge Cox at the sentencing. (The prosecutors and Schmidt’s attorney, David DuMouchel, declined to be interviewed.) If one believes the prosecutors and Schmidt — that Winterkorn was unmistakably informed of the cheating at the meeting — the CEO’s response to that information looked suspiciously like a cover-up. Winterkorn did not direct his subordinates to notify authorities about the cheating or launch an investigation to determine exactly what had happened. Instead, he sent Schmidt on a mission to persuade U.S. regulators to allow the sale of 2016 VWs. Winterkorn “directed Mr. Schmidt to seek an informal meeting with a senior-ranking CARB official he knew from his time in the U.S.,” according to Schmidt’s sentencing memo. “Rather than advocate for disclosure of the defeat device to U.S. regulators,” the FBI agent alleged in his affidavit, “VW executive management authorized its continued concealment.” Before leaving on his mission, Schmidt “sought and obtained approval for the ‘storyline’ he intended to convey during his meeting with CARB,” Schmidt’s memo asserted. The script was approved by at least four senior VW officials below Winterkorn, according to the memo, which added, “Mr. Schmidt was instructed not to disclose the defeat device or any intentional cheating.” In August 2015, Schmidt flew from Germany to Michigan, where he successively lied to two CARB officials. He emailed “detailed updates” to his boss in Germany and ten other “senior people,” conveying that “he was following the script of deception and deceit that VW, with Schmidt’s input, had chosen,” prosecutor Singer stated. Finally, a different VW engineer, unable to stomach the deceit any longer, went off-script and confessed to CARB during a meeting on August 19. A VW supervisor formally conceded use of the defeat device to regulators on September 3, and the EPA and CARB made VW’s confession public on Sept. 18, 2015. Winterkorn stepped down five days later, asserting that he was “stunned” by the events of “the past few days,” adding that he was “not aware of any wrongdoing on my part.” The company’s supervisory board exonerated him the same day, stating that he “had no knowledge of the manipulation of emissions data.” In testimony before the German Parliament in January 2017, Winterkorn insisted he had never even heard the phrase “defeat device” until the scandal erupted publicly. On four occasions that day he declined to answer legislators’ questions, citing ongoing criminal inquiries by German prosecutors. So far, the Schmidt sentencing in Detroit is the ex-CEO’s closest brush with American criminal justice. Twenty-seven months after the conspiracy was exposed, Winterkorn has not been charged with any offense in either the United States or Germany. (His U.S. counsel declined comment for this article.) Will he ever be? Will anyone higher up the ladder than Oliver Schmidt ever answer for this remarkable crime? The answers to those questions remain very unclear. U.S. prosecutors want to indict Winterkorn, but have not yet received approval from the brass at the Department of Justice, according to two sources familiar with the process. That would seem like a huge step. Yet in truth, a U.S. indictment of Winterkorn or other top VW figures is increasingly becoming moot simply because the prosecutors can’t gain access to most of the key figures in the case. Winterkorn hasn’t set foot in the U.S. since the scandal broke and, after Schmidt’s crushing sentence, is not likely to do so anytime soon. Among the eight VW engineers charged in the U.S., only Schmidt and James Liang, a non-supervisor sentenced to 40 months this past August, are actually in the U.S., and only one other — an Audi engine development supervisor, Zaccheo Giovanni Pamio, who happens to be an Italian national — is extraditable. That means the judicial focus is shifting to Germany. There, three sets of prosecutors are certainly going through the proper motions. The authorities in Braunschweig — acting for the state of Lower Saxony, where both the parent company, VW AG, and its VW brand passenger car unit are based — say they are investigating 39 individuals for fraud in connection with Dieselgate, one for obstruction of justice, and three for financial market manipulation (which in this instance would mean the failure to promptly disclose the gestating crisis to shareholders). In Munich, Bavarian prosecutors are looking at 13 individuals at VW’s Audi unit, based in Ingolstadt, for fraud and false advertising. And in Stuttgart, three executives are under scrutiny for market manipulation. The two market manipulation inquiries focus on Winterkorn and three very senior current VW officials. The Braunschweig prosecutors, for instance, are looking at supervisory board chairman Hans Dieter Pötsch (who was CFO when the scandal broke) and current VW brand manager Herbert Diess, while the Stuttgart authorities are scrutinizing Pötsch and current CEO Matthias Müller. (VW declined to comment on the record for this article other than to provide a written statement in which it asserted that its executives fully complied with disclosure laws.) Yet progress is strikingly slow. There have been only two German arrests so far. One was of Pamio; the other was of Wolfgang Hatz, a senior supervisor at, successively, Audi, VW, and Porsche. German prosecutors do not confirm the identities of detained individuals or what they’re charged with, but the Munich probe is focusing on fraud and false advertising, the office says. We may not see many criminal prosecutions in Germany, let alone convictions or lengthy sentences. The country’s law presents many serious hurdles. There’s no criminal liability for corporations, for starters. There’s no statute barring a criminal conspiracy, no relevant criminal clean air law, and no law against lying to regulators or investigators. (The latter is actually protected by the robust German right to silence, according to Carsten Momsen, a law professor at Berlin’s Free University.) Prosecutors’ tools to reward and turn perpetrators into state witnesses are weaker than those wielded by their American counterparts. And some of the criminal laws that do exist — written to catch individuals who swindle other individuals — may be ill-suited to capturing the corporate machinations that happened in this case. The result is breathtakingly different outcomes for both the company and its customers in the two countries. In the U.S., the system has delivered swift consequences. Facing harsh corporate criminal sanctions, flexible and draconian criminal laws, and streamlined consumer class-action procedures, Volkswagen quickly capitulated. Within nine months — breakneck speed in the legal realm — it agreed to pay roughly $15 billion in civil compensation and restitution to consumers and federal and state authorities for the 2.0-liter cars involved, and the sum has since crept up to more than $25 billion, as deals were reached for the 3.0-liter cars, and for criminal fines and penalties. Volkswagen has bought back or fixed most of the offending vehicles, and customers have received thousands of dollars per car in compensation for a variety of losses, including the deception itself and diminished resale value. The company pleaded guilty in April to federal criminal charges of conspiracy, fraud, making false statements and obstruction of justice. VW gave U.S. prosecutors liberal access to the fruits of an investigation it commissioned by the Jones Day law firm, which conducted more than 700 interviews and collected more than 100 million documents. (The inquiry is ongoing, according to VW.) VW also helped recover forensically thousands of pages of documents that had been deleted by scores of VW employees in the final days of the conspiracy. In return, U.S. prosecutors gave the company credit for cooperation, slicing 20% from its criminal fine, which came to $2.8 billion even after the reduction. In Canada, too, the company has paid compensation, including a $290 million deal for 3.0-liter cars just reached in January. And in South Korea, Volkswagen also paid dearly, receiving record fines and seeing eight local VW and Audi officials charged criminally, with one now serving an 18-month prison term. Yet in Germany and Europe, it’s been a totally different story. There, VW has not offered compensation to any customer. In Germany, where the key decisions were made and all the decision makers reside, no criminal or administrative fines or penalties have yet been imposed. |

|

大众的“配合”给美国检方留下了极其深刻的印象,但却只限于美国境内。例如,大众并未向德国检方递交Jones Day的资料。公司去年4月称,发布Jones Day调查结果总结报告将违背其一再做出的承诺。大众称,面向公众发布的声明中附带了认罪答辩,而且已经揭示调查的重大发现,但任何进一步的声明将破坏正在进行的调查或与其答辩协议相冲突。然而,这份只有30页、字间距为两倍行距的认罪协商文件并未提及任何人的姓名(检方文件一般都会提及),可谓是异常谨慎。例如,该文件仅用一句话描述了2015年7月27日的会见,而该会见在施密特起诉案中至关重要。(文件说,召开了一场会议,但是没有描述讨论的内容或高管是否出席。) 即便德国执法机关采取了强有力的举措,该案到目前为止一直都面临着重重阻碍。去年3月,慕尼黑当局搜查了Jone Day的德国办事处,并收缴了公司有关大众调查的资料。但联邦宪法法庭在Jones Day的要求下临时阻碍了其查阅文件,同时慕尼黑当局则忙于解决律师客户特权和受调查雇员隐私权等问题。莫森教授指出,德国法院的判例法在这些问题上出现了重大分歧。 “作弊装置”在美国和欧洲的定义是相同的。不管怎么样,大众认为这一软件在北美之外是合法的。德国联邦汽车交通局(又称KBA)——因其对柴油监管政策的不严谨而臭名昭著——于2015年拒绝承认大众的上述理论。 大众还坚持认为,非美国客户并未受到侵害。鉴于美国之外地区宽松的NOx浓度限制,大众认为,大多数轿车可以通过简单的软件调整来彻底解决这一问题。然而,令很多工程师难以想象的是,大众何以在不降低燃油经济性和破坏排放控制装备寿命的前提下,仅靠软件来解决NOx排放问题,而这些问题正是导致大众进行作弊的诱因。德国联邦汽车交通局和其他德国监管方已批准对软件进行调整,但并未发布能够说明汽车召回效果的任何测试结果。国际清洁运输理事会的尤安•伯纳德认为,“大众无法在不替换硬件的前提下解决NOx排放问题。”西弗吉尼亚大学曾于2014年委托该理事会开展调查,首次曝光了大众使用作弊装置的事件。 海外原告律师正在就柴油门事件在欧洲起诉大众。但是,与刑事部门一样,他们面临着一系列障碍。依据欧盟规定,购买了涉案车辆的800万欧盟客户在理论上可以在大众总部所在地下萨克森州起诉大众。但德国没有消费者集体诉讼一说。此外,原告所拥有的发现权非常有限,律师也拿不到胜诉酬金,而且发起诉讼的原告还得承担风险:如果败诉,他们不仅得支付自身的法律费用,还得承担被告的一部分费用。 诚然,大众并非是无罪。它也可能会收到来自于德国检方或联邦金融监管局(类似于美国证券交易委员会)开出的数亿欧元罚单。 两组原告——大众股东和大众柴油车车主——正试图克服这些障碍,发起民事诉讼。其中更有威慑力的莫过于德国股东,他们称大众未能披露这一正在发酵的丑闻。原告律师将使用“模型”诉讼机制,这是一种仅适用于股东诉讼案件的类集体诉讼,计划于9月在布伦施威格地区高等法院开庭。但这一流程预计将耗费数年的时间,而且最终获得的赔偿金额可能只能占到索赔额度的一小部分(索赔额95亿欧元,约合112亿美元),这取决于法庭如何对大众危机披露时间是否过晚进行定性。与此同时,一种创新的“团体诉讼”已于去年11月在布伦施威格展开,它代表了德国消费者团体——15347名大众柴油车车主移交了其索赔主张,由美国律所Hausfeld柏林办事处发起。 说到公平,考虑到欧洲和美国之间政治、社会和监管环境的巨大差异,大众可能更容易为自己在海外的不配合行为找到说辞。自丑闻爆发之后,进一步的测试显示,柴油排放造假是欧洲普遍存在的问题。2016年12月,欧盟委员会开始调查德国监管当局和其他6个欧盟成员国是否放松了对柴油排放的监管力度。虽然与其他大多数案例相比,大众的作弊方式更加露骨,但其柴油车在美国之外地区的NOx排放量并不比其对手高。此外,宝马、菲亚特克莱斯勒、戴姆勒(奔驰制造商)、PSA(标志和雪铁龙制造商)以及雷诺尼桑在过去一年中均因潜在的柴油车排放不达标问题而遭到了德国或法国当局的调查。 很明显,虽然大众的所作所为非常过分,但即便是在美国,大众也并非是个例。5月,美国司法部起诉菲亚特克莱斯勒在10.4万辆2014-16年的Jeep Grand Cherokees车型以及1500辆道奇Ram皮卡(美国最畅销的柴油皮卡)上安装了作弊装置。(菲亚特克莱斯勒拒绝承认存在这一不当行为,并正在进行和解谈判。) 在欧洲,尤其是德国,工业、劳工甚至环保政策都更加支持柴油车的生产。监管力度并不大,违规的惩罚也很轻,而且为了让本国汽车制造商能够与邻国竞争,国家监管方也不愿为其设立障碍,因为他们认为邻国监管方在这一方面也是睁一只眼闭一只眼。 然而,柴油门250亿美元的罚金改变了欧洲的政治格局。丑闻让人们开始关注一个蓄积已久的健康问题,而且这个问题的罪魁祸首实际上并不止大众一家企业,而是整个柴油车行业以及滋养和保护这一产业的政治文化。例如,欧洲政府报告显示,每年有7.2万名欧洲居民因NOx排放而丧生。 2月份,莱比锡行政法院将对名为德国环保行动倡议组织所提起的诉讼做出审判,最终可能会导致德国70个城市出现柴油车禁令。柴油车销量如预料那样出现了大幅下滑。12月,大众首席执行官马希尔斯·穆勒在接受一家报纸采访时指出,欧洲废除长期执行的柴油行业主要税收补贴的时候到了。此语一出,一片哗然。 欧洲和美国之间监管、环保和文化差异正在缩小。但是,正是由于·施密特跌入了深渊。这么看来,施密特为此付出惨痛代价的事实存在一定的不公正性。然而,如果所有的后果都由他一人来承担,那么事情将变得更加不公平。 在丑闻爆发之后,柴油门事件的大致情形很快浮出水面。自那之后,刑事、民事和媒体调查所搜集和提交(或泄露)的证据一点一点地积累起来,更加清晰地揭露了大众阴谋广泛的覆盖面。当人们在掌握了这些信息之后再审视公司的过往行为时会发现,公司的高层必然已经知晓此事,而且其背后也不断折射出首席执行官文德恩的影子。 2006年,大众发起了一项策略,试图通过营销更加清洁的柴油车,重振当时停滞不前的美国销售业绩。这一策略所面临的挑战在于,柴油引擎的NOx排放量比汽油引擎大,而且美国NOx法规要比欧洲严格的多,仅为欧洲排放标准的六分之一。大多数减少NOx排放量的方法都会降低燃油经济性,或需要频繁的保养。(从环保上来看,欧洲专注于降低温室气体,包括二氧化碳。柴油因其卓越的燃油经济性,能够非常好地降低碳排放。但柴油车还会产生能够引起雾霾的NOx。正是因为洛杉矶历史上的雾霾问题,加州空气资源委员会和美国环保署的监管人员长期以来一直对NOx所带来的健康危害比欧洲方面更为敏感。) 大众的美国策略出自首席执行官毕睿德之手,而且在文德恩2007年1月接替了他的位置之后得以延续。2008年初,文德恩宣布了一个10年期计划,要求在2018年之前让公司的美国销量翻三番,从而让其超过通用和丰田,成为世界领先的汽车制造商。这一计划在2015年中期之前获得了成功,其关键点便是清洁柴油车。 |

VW’s “cooperation,” which so impressed American prosecutors, hasn’t extended beyond U.S. borders. Volkswagen has not shared the Jones Day materials with German prosecutors, for instance. And last April, the company revealed that it would be breaking its repeated promise to issue a report summarizing the results of the Jones Day inquiry. VW said the public statement of facts that accompanied its guilty plea revealed the inquiry’s key findings, and that any further announcement would risk undermining ongoing investigations or conflicting with its plea agreement. But the plea bargain document is just 30 double-spaced pages, identifies nobody by name, and, as prosecutorial documents often do, plays its cards close to the vest. It includes only one sentence, for instance, about the July 27, 2015, meeting that was so central to the Schmidt prosecution. (It states that a meeting took place, but gives no hint of what was discussed or that senior executives were present.) Even when German law enforcement has taken aggressive action, it has been stymied so far. Last March Munich authorities raided Jones Day’s German offices and seized materials from the firm’s VW investigation. But the Federal Constitutional Court has temporarily blocked their examination, at Jones Day’s request, while it sorts out issues of attorney-client privilege and the privacy rights of interviewed employees. German court precedents are deeply divided on these questions, according to professor Momsen. The definitions of “defeat device” in the U.S. and E.U. are nearly identical. Nevertheless, VW contends the software was lawful outside North America. Germany’s Federal Motor Transport Authority, or KBA — notoriously lax in its diesel oversight policies — rejected this theory in December 2015. The company has also insisted non-American customers suffered no injury. Because of more lenient NOx limits abroad, it maintains, most of those cars could be fully addressed with simple software fixes. Yet many engineers can’t fathom how software alone could possibly repair a NOx problem without correspondingly reducing fuel economy and undermining the durability of the emissions control equipment — the very problems that led VW to cheat in the first place. The KBA and other national regulators have approved these fixes, but haven’t released any test results shedding light on what the recalls achieved. “VW could not do miracles regarding NOx emissions without replacing the hardware,” argues Yoann Bernard of the International Council on Clean Transportation, which commissioned the 2014 study by West Virginia University that first revealed VW’s use of a defeat device. Plaintiffs lawyers abroad are suing VW over the affected diesels there. But, like the criminal authorities, they are hampered by a slew of handicaps. Under E.U. rules, all 8 million E.U. customers who bought Dieselgate cars could theoretically sue in Lower Saxony, where VW AG is based. But in Germany there are no consumer class actions. In addition, plaintiffs have very limited discovery rights; lawyers are prohibited from accepting contingency fees; and plaintiffs who sue run the risk that if they lose, they will have to pay not just their own legal fees, but a portion of their adversary’s, as well. To be sure, VW isn’t yet in the clear. It may yet be hit with penalties worth hundreds of millions of euros, imposed by German state prosecutors or by the BaFin, the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (something like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission). And two groups of plaintiffs — VW shareholders, and owners of VW diesels — are attempting to overcome the obstacles to civil litigation. The bigger threat comes from German shareholders, who allege that VW failed to disclose the budding scandal. Plaintiffs lawyers are using a “model” litigation mechanism, a class action analog available only for shareholder suits, which is scheduled to begin in September in the Higher Regional Court of Braunschweig. But that procedure is expected to take years and the amount recovered may be a fraction of the huge sums sought (€9.5 billion, or $11.2 billion), depending on how early or late the court concludes VW should have disclosed the crisis. At the same time, an innovative “group action” was filed in Braunschweig in November on behalf of a German consumer group — to whom 15,347 VW diesel owners had assigned their claims — by the Berlin office of the American law firm, Hausfeld. In fairness, Volkswagen’s obstructive stance abroad may be more defensible when one considers the vast divide between the political, social, and regulatory milieus in Europe and the U.S. Since the scandal broke, further testing has made clear that cheating on diesel emissions was endemic across Europe. In December 2016 the European Commission began investigating whether regulatory authorities in Germany and six other E.U. nations have been lax in their oversight of diesel emissions. Though VW’s cheating was, in most instances, more brazen in methodology, its diesels’ NOx emissions outside the U.S. appear to have been no worse than their competitors’. Moreover, BMW, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, Daimler (maker of Mercedes), PSA (maker of Peugeots and Citroëns), and Renault-Nissan have all come under scrutiny over the past year by either German or French authorities for possible diesel emissions irregularities. (The manufacturers deny wrongdoing.) Even in the U.S., it’s become clear, VW’s conduct — though still the most egregious — was not unique. In May the Justice Department sued Fiat Chrysler for having allegedly placed a species of defeat device on 104,000 model year 2014-16 Jeep Grand Cherokees and Dodge Ram 1500 pickups, the most popular diesel pickup sold in America. (FCA, which denies wrongdoing, is in settlement negotiations.) European and, especially, German industrial, labor, and even environmental policy favored the production of diesel cars. Regulatory oversight was slight, penalties for violations were trifling, and national regulators were disinclined to handicap their home country’s carmakers vis-à-vis those of neighboring countries, whose regulators were presumed to be winking at the same gamesmanship. Dieselgate’s $25 billion consequences in the U.S. have transformed the political landscape in Europe, however. The scandal has drawn attention to a long simmering public health issue that, it turns out, was not caused by Volkswagen alone, but rather by the diesel car industry and the political culture that nurtured and protected it. For example, a European government report has found that 72,000 EU residents die prematurely each year because of NOx emissions. In February the Administrative Law Court in Leipzig will decide a case brought by an advocacy group called Environmental Action Germany that could eventually result in diesel car bans in as many as 70 German cities. Diesel auto sales are dropping precipitously in anticipation, and in December VW CEO Matthias Müller shocked the automotive world by suggesting in a newspaper interview that the time had come for Europe to abandon key tax subsidies that have long supported the diesel industry. The regulatory, environmental, and cultural gap between the E.U. and the U.S. is closing. But it was that chasm that spawned Dieselgate, and that chasm that Oliver Schmidt toppled into. So there is some injustice in the fact that Schmidt will pay so dearly. Yet there will be even greater injustice if he is the only one to do so. The key contours of the Dieselgate affair emerged soon after the scandal broke. Since then the slowly accumulating evidence amassed and presented (or leaked) from criminal, civil, and media investigations have only made the breadth of VW’s conspiracy clearer. Examining the chronology of the company’s behavior in light of that information leaves little doubt that knowledge of the wrongdoing reached high up the ranks, repeatedly coming within a whisker of CEO Winterkorn himself. In 2006, Volkswagen initiated a strategy to revive its then-moribund U.S. sales by marketing a clean diesel car. The challenge was that diesels produce more NOx than gasoline engines, and American NOx regulations were far more stringent than Europe’s — permitting only about one-sixth of what Europe then allowed. Most ways of cleaning NOx reduced fuel economy, harmed performance, took up space, increased cost, or required frequent servicing. (Environmentally, Europe had focused on reducing greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide. Diesels, due to their excellent fuel economy, were great at reducing carbon emissions. But diesels also produced NOx, which causes smog. Because of the history of smog problems in Los Angeles, regulators from CARB and the EPA had long been more sensitive to the health dangers posed by NOx than their European counterparts.) VW’s U.S. strategy was born under then-CEO Bernd Pischetsrieder, and continued when Winterkorn replaced him in January 2007. In early 2008, Winterkorn announced a 10-year plan which called for tripling the company’s U.S. sales by 2018, enabling it to surpass General Motors and Toyota to become the world’s leading automaker. Clean Diesel was the linchpin of the plan, which, by mid-2015, had succeeded. |

|

文德恩由大众监事会主席费迪南德·皮耶希一手提拔。(德国公司有两个董事会:一个由高级管理人员组成的管理委员会,另一个是非执行董事组成的监事会。)皮耶希从1993年到2002年担任首席执行官,被认为是公司有史以来最有影响力的人物。他一方面是天才工程师,也是非常有预见性的领袖,但他也有无情的一面; 皮耶希曾高调指出,如果高管未能及时拿出优异的业绩,自己就会毫不留情地解雇他们。 大众的文化向来傲慢,只是考虑到其在国家经济中的重要地位,外界也就不那么在意罢了;大众高管与德国政治家关系密切; 还有不寻常的准公用事业地位(下萨克森州政府掌握着大众20%有投票权的股票)。皮耶希曾卷入过重大丑闻,包括20世纪90年代的企业间谍事件(后来与通用汽车达成了1亿美元的和解协议),以及2004年曝出的长达近十年的劳工丑闻(期间公司一直在贿赂劳工代表和政客)。去年6月,美国前副总检察长拉里·汤普森因大众美国“认罪答辩”的规定而担任大众的外部监督人。12月,他对德国的一家报纸表示,大众的“企业文化腐败”,且缺乏“公开和诚实的态度”。 皮耶希器重文德恩的原因在于,文德恩是拥有博士学位的工程师,曾担任质量监控主管,以完美主义和微管理出名。几年之后,令《福布斯》杂志对2011年文德恩访问田纳西州查塔努加大众工厂(该工厂负责制造部分柴油机)的事件进行了报道,而且令杂志感到百思不得其解的是,文德恩“不下七次”前往工厂,亲自督导2012年款帕萨特在美国的发售事宜。“他会亲自驾驶早期原型车,”文章接着称,“而且会仔细检查产品质量,用口袋里随身携带的千分尺测量车身板之间的小缝隙。一位美国高管回忆说,哪怕是微小油漆缺陷也逃不过这位原质检主管的眼睛。‘他能发现所有毛病。’” 在毕睿德和文德恩领导下,两组工程师对制造适合美国市场的柴油车这一难题进行了攻坚。至少在大众看来,这是一个异常艰巨的任务,因为美国的环保法规极其严格。大众高级主管沃尔夫冈·哈茨(在德国被捕之后)2007年在一份录像中曾抱怨加利福尼亚州的规定,这段话后来被多次提到,而且看起来有点像某种预言。“加州空气资源委员会一点也不现实,”他说,“虽然我们可以做很多工作,也有这样的愿意,但我们无法完成不可能完成的任务。” 鉴此,位于不同城市的两组大众工程师接手了这一任务。一组为大众和奥迪品牌设计2.0升发动机。第二组来自于奥迪,致力于为两个品牌的SUV和豪华车系列设计3.0升发动机。 两组工程师很快找到了相同的解决方案:作弊装置。目前还不清楚两组工程师是否均独立研发了这一装置;目前美国检方尚未指控存在同谋行为。早在1999年奥迪就开发过作弊软件,并安装在2004年到2006年间在欧洲推出的V6 SUV车型上。 当早期作弊软件据称已安装在欧洲市场的奥迪车上时,文德恩很快便要采取行动。当时他担任奥迪公司首席执行官,而据说是文德恩心腹的哈茨当时是奥迪发动机开发负责人。2007年文德恩成为大众汽车首席执行官后,提拔贺哈茨执掌大众汽车发动机的开发业务。 美国检方称,2006年到2015年期间,先后执掌大众发动机开发业务的四名负责人都知道作弊软件的存在,最早2006年就已经知道,而且大众负责废气控制的负责人也全都知道。五人中有三人因串谋诈骗和虚假陈述在美国被起诉。但三人都身在德国,美国检方无权引渡。(这五个人在底特律的刑事诉讼中均没有提交法律文书,其中两人的律师拒绝发表评论,而ProPublica也联系不上其他人)。五人在德国均未被起诉。 据美国检方透露,“奥迪高管层”早在2008年就已知道欺诈软件的存在。检方称,2008年1月,奥迪高管层就曾派代表萨切奥·帕米奥和其他奥迪高级经理向集团负责人汇报,警告说使用作弊软件可能是非法行为,在美国可能会带来“非常严重的问题”。2008年7月,奥迪环保认证团队在信中对帕米奥说,这款软件“风险极高”。然而作弊软件安装一直在继续。(去年7月,帕米奥以串谋、电信诈骗和虚假陈述的罪名遭底特律联邦法院起诉,当月他被慕尼黑警方逮捕,律师拒绝置评。) 2011年,作弊行为蔓延到另一个城市里第三个大众品牌,而高管似乎也有更多机会得知作弊情况。当时大众刚刚收购保时捷,位于斯图加特的保时捷工程师希望改装奥迪3.0升柴油发动机,用于美国市场的保时捷的SUV品牌卡宴。根据纽约州总检察长办公室提出的民事诉讼,奥迪工程师于当年9月向保时捷工程师介绍了作弊软件的工作原理,随后保时捷便采用了欺诈技术。此时,文德恩已将哈茨调往保时捷担任研发主管。他曾担任保时捷管理委员会成员,与大众现任首席执行官穆勒共事。 |

Winterkorn was the protégé of the chairman of VW’s supervisory board, Ferdinand Piëch. (German companies have two boards: a management board, composed of top executives, and a non-executive supervisory board.) Piëch, who had been CEO himself from 1993 to 2002, was considered the most influential figure in the company’s history. A gifted engineer and prophetic leader, he was also ruthless; Piëch boasted about his willingness to fire executives if they didn’t deliver quickly. VW had an arrogant culture, shielded by the vital role the company plays in its nation’s economy; its officials’ cozy relationship with German politicians; and its unusual quasi-public status (the state of Lower Saxony controls 20% of its voting stock). Piëch had survived major scandals, including a corporate espionage debacle in the 1990s, which led to a $100 million settlement with General Motors, and a nearly decade-long labor scandal that surfaced in 2004, in which the company made illegal payments to labor representatives and politicians. The company had a “corrupt corporate culture,” lacking in “openness and honesty,” former deputy U.S. attorney general Larry Thompson, who became VW’s outside monitor in June under the terms of its U.S. guilty plea, told a German newspaper in December. In Winterkorn, Piëch selected a Ph.D. engineer and former quality assurance chief with a reputation for perfectionism and micromanagement. Just a few years later Forbeswould comment with wonder at how, in 2011, he visited the VW factory in Chattanooga, Tenn. — where some diesels were manufactured — “no less than seven times” to oversee the U.S. launch of the 2012 Passat. “He drove early prototypes,” the article continued, “and pored over initial quality, using a micrometer he carries in his pocket to measure the tiniest of gaps between body panels. Even minor paint flaws didn’t escape the former quality manager, one American executive recalled. ‘He finds everything.’ ” Under Pischetsrieder and then Winterkorn, two sets of engineers attacked the riddle of how to build a diesel passenger car for the U.S. market. It was a tall order, given how draconian U.S. environmental regulations were, at least in the company’s view. A high-level VW supervisor, Wolfgang Hatz (since arrested in Germany), was captured on video in 2007, complaining about California’s rules in a widely repeated remark that would come to be seen as prophetic. “The CARB is not realistic,” he said. “We can do quite a bit, and we will do a quite a bit. But impossible we cannot do.” And so the two sets of VW engineers, located in different cities, embarked on their missions. One group would design the 2.0 liter engines for both VW and Audi cars. A second set, from Audi, would design the 3.0 liter engines for SUVs and luxury vehicles for both brands. Both groups quickly homed in on the same solution: a defeat device. It is unclear whether they acted independently; to date U.S. prosecutors have not alleged coordination. Each group was aware of, and adapted, a variant of the cheating software that Audi had developed as far back as 1999, and had in its diesel V6 SUVs in Europe from 2004 to 2006. At the time that the earlier cheating software was allegedly being implemented on Audis in Europe, Winterkorn was already just a couple steps from the action. He was CEO of Audi, while Hatz — reportedly a Winterkorn confidant — was Audi’s head of engine development. When Winterkorn became CEO of VW AG in 2007, he promoted Hatz to head engine development for VW AG. A succession of four top supervisors for engine development for the VW Brand, serving from 2006 to 2015, all knew about the cheating software, as did, from as early as 2006, the head of exhaust control measures for all of VW AG, according to U.S. prosecutors. Three of these five individuals have been indicted in the U.S., for conspiracy to commit wire fraud and making false statements. But all are in Germany, beyond the prosecutors’ extradition powers. (None have filed papers in the Detroit criminal proceedings. Lawyers for two of them declined comment, and the others could not be reached by ProPublica.) None of the five have been charged in Germany. News of the fraudulent software reached “senior Audi managers” as early as 2008, according to U.S. prosecutors. In January 2008, they assert, members of that team sent a presentation to the head of the group, Zaccheo Pamio, and other senior Audi managers, warning that the software solution was possibly illegal and “highly problematic in the U.S.” In July 2008, a member of Audi’s environmental certification team wrote Pamio that the software was “indefensible.” The plan went forward, nonetheless. (Last July, Pamio was charged in federal court in Detroit with conspiracy, wire fraud, and making false statements. That same month he was arrested by Munich authorities. His lawyers declined comment.) In 2011, the cheating spread to a third VW brand in another city, seemingly creating still more opportunities for word to leak up to executives. VW had just acquired Porsche, and Porsche engineers in Stuttgart sought to adapt Audi’s 3.0-liter diesel engine for use in a Porsche Cayenne SUV for the U.S. market. That September Audi engineers explained to Porsche engineers how the cheat software worked, according to a civil complaint filed by the New York State Attorney General’s Office, and Porsche adopted the fraudulent technology. By this time Winterkorn had moved Hatz to Porsche as head of research and development. He served on Porsche’s management board, where he worked alongside VW’s current CEO, Müller. |

|

与此同时在狼堡,2.0升柴油机排气系统存在的问题也让公司的高层(文德恩的亲信们)了解到了作弊软件的存在。工程师梁发现NOx处理设备硬件故障率异常之高。他认为出现问题的原因是设备使用太频繁,不仅在实验室测试期间会启动,有时也会在车辆行进过程中启动。他建议改进作弊软件,以确保仅在测试时启动排气处理功能。 据美国检方称,2012年7月,梁和其他工程师约见了汉斯-雅各布·诺伊塞尔和贝恩德·高德维。当时诺伊塞尔是大众汽车发动机开发负责人。高德维是握有实权的产品安全委员会成员,直接向大众汽车质量管理负责人弗兰克·图赫汇报。大众内部杂志报道称,图赫每周都与文德恩会面。高德维是文德恩的亲信,有时被称为大众的“消防员”——专门负责解决难题。 梁提出的解决方案获得了批准,2013年年中出品的新一代大众柴油机上安装了更先进的作弊软件。此外,2014年召回旧款车型就是为了改装作弊软件。然而大众告诉消费者和监管人员,召回是为了调整仪表板的警示灯,并解决某些环保问题。(诺伊塞尔和高德维在美国被指控存在串谋、诈骗和虚假陈述,但在德国没有被起诉,诺伊塞尔的律师拒绝发表评论,也无法与高德维取得联系。) 按美国检方的说法,2013年年底,奥迪高层获悉了在3.0升发动机上安装作弊软件的事情,这为叫停作弊软件的行为提供了另一个机会。考虑到环境认证部门管理者提出的担忧,一位奥迪工程师让员工准备了演示文件,向“当时的奥迪高管和品牌管理委员会成员”详细描述了作弊软件的工作原理。发送演示文件的工程师建议所有收件人在下载后应立刻删除邮件和附件。 同月,奥利弗·施密特看到了另一份关于奥迪欺诈软件的演示。 “最好把封面上的人名删掉,”事后施密特在电子邮件中说,“如果此类文件落在当局手中,大众可能会遇到大麻烦。” 2014年3月,有关大众内部存在犯罪行为的重大线索开始在汽车行业圈子里流传,很快便传到了高德维和图赫的耳中,随后文德恩也得知了这一消息。在一次行业会议上,西弗吉尼亚大学的研究人员提交了一份将于5月出版的研究报告。他们调查了三款在美国市场随机选择的柴油车排放情况。宝马X5表现不错,但大众捷达和大众帕萨特表现可疑,它们在实验室中通过了测试,然而其实际驾驶时的NOx排放值可高达法定标准的35倍。 |

Meanwhile, in Wolfsburg, problems with the 2.0-liter diesel exhaust systems were forcing knowledge of the cheat software further up the corporate hierarchy to people who knew Winterkorn personally and well. Engineer Liang had learned of unusually high numbers of hardware failures involving the NOx treatment equipment. The problem, as he diagnosed it, stemmed from the fact that the equipment was being used too much — not just during lab testing, but sometimes on the road. He proposed refining the cheat software to ensure that full exhaust treatment would be triggered solely during testing. In July 2012 he and other engineers met with Hans-Jakob Neusser and Bernd Gottweis, according to U.S. prosecutors. Neusser was then head of engine development at the VW brand. Gottweis was a member of the powerful Products Safety Committee, answering to the head of quality management at VW AG, Frank Tuch. Tuch met weekly with Winterkorn, according to an account in VW’s in-house magazine. Gottweis was a close confidant of Winterkorn and was sometimes referred to as “the fireman” at VW — someone who put out fires. Liang’s solution was approved, and his more finely tailored defeat device was installed on the next generation of VW diesels, which arrived in mid-2013. In addition, a recall was carried out in 2014 to retrofit older models with the tweaked software. Customers and regulators were told that the recall was to fix a dashboard warning light and address certain environmental issues. (Neusser and Gottweis have been charged in the U.S. with conspiracy to commit wire fraud and making false statements in the U.S; neither has been charged in Germany. Neusser’s attorney declined comment, and Gottweis could not be reached.) In late 2013, the fact that cheat software was being used in 3.0 liter engines reached the top echelons of Audi, according to U.S. prosecutors, presenting still another opportunity for someone to blow the whistle. An Audi engineer, prompted by the concerns of a manager in the environmental certification department, had his people prepare a presentation to a “then-senior executive and member of Audi’s brand management board,” describing in detail how the software worked. The engineer who sent the presentation advised every recipient to delete the email and attachment after downloading it. That same month, Oliver Schmidt saw a different presentation about Audi’s fraudulent software. “It would be good if you deleted us from the cover page,” Schmidt emailed afterwards. “If such a paper somehow falls into the hands of the authorities, VW can get into considerable difficulties.” In March 2014, the biggest clue about the criminal conduct festering within VW began filtering out into the automotive community, soon reaching Gottweis, Tuch, and, through them, Winterkorn. At an industry conference, researchers at West Virginia University presented a study, which would be published in May. They had studied the emissions of three randomly selected diesel cars available in the U.S. A BMW X5 had done fine, but a VW Jetta and VW Passat had each performed suspiciously, passing the test in the lab, but emitting up to 35 times the lawful NOx limit during real-world driving. |

|

在沃尔夫斯堡,由诺伊塞尔和高德维等人领导的大众工程师成立了一个特设委员会,专门应对这一研究报告。检方称,特设委员会的目的是针对监管机构可能提出的问题设计回避和误导性的回应。 2014年5月23日,高德维围绕西弗吉尼亚大学研究,写了一篇在当前看来实属无耻的报告。当天图赫将其与其他定期的周末阅读材料一起交给了文德恩。(2015年10月大众决定暂停图赫的职务,图赫于2016年2月辞职。我们无法联系上他,并让其发表评论。) 2016年,德国媒体《图片报》刊登了这份备忘录,批评文德恩的人士将其看作是确凿的证据。“公司不能向监管部门详细解释NOx的排放量为何急剧增加,” 高德维写道,“否则监管部门可能会展开调查”,以检查大众是否使用了“作弊装置”,随后他又解释了作弊装置的为何物。他指出,有个团队正在对软件进行调整,这个新软件能够“降低实际驾驶期间的排放量”,“但排放量依然不符合标准。” 大众宣称,高德维报告中的内容无法让首席执行官得出这是一个重大违规事件的结论,而它有可能只是经常出现的产品缺陷。 “这份备忘录只不过提到,美国监管机构有可能会调查是否使用了作弊装置。” 2016年8月大众律师在驳回美国股东诉讼的动议中写道, “备忘录并没有说明或暗示汽车实际已经安装了作弊装置,也没有说美国监管部门发现作弊装置之后的后果,也没有解释如果监管部门发现后可能会出现多大的财务风险。” 律师在美国民事诉讼中提交的法律文书中称,文德恩承认收到过这份报告,“但是不记得周末有没有看过。”他还承认,2014年5月便已知道西弗吉尼亚大学的研究,此时距离排放门事件曝光还有15个月。但该文件称,“他相信,公司的一个工作组正在努力解决这一问题。” 其中一个工作组确实在努力。一年多时间里,包括梁在内的大众工程师想尽办法向加州空气资源委员会和美国环保署的监管人员撒谎。他们甚至向监管机构承诺,公司将通过修复软件来解决问题,同时还于2014年底发起了另一次召回。 2014年11月,文德恩收到了一份关于召回的单页备忘录,其中提到软件修复估计需要花费2000万欧元。对于2014年的净营业利润达127亿欧元的大众来说,这点钱简直可以忽略不计。文德恩在德国议会作证时表示,有关人员在备忘录中向他保证,这一问题已经得到解决。 但2015年初加州空气资源委员会发现,召回车辆实际驾驶时的NOx排放依然超标。 当时,在密歇根州奥本山市大众环境办公室工作了三年的奥利弗·施密特已经升职。2015年2月他回到狼堡,成为了诺伊塞尔的三位副手之一。当时他担任大众品牌开发总监,手下有10,000名员工。 7月,加州空气资源委员会向大众工程师表示将拒绝认证2016年的柴油汽车,直到大众能给出合理的解释。因此2015年7月27日,施密特和一位同事向文德恩和其他高管回报了这一情况,与会者包括当时负责大众轿车部门的高管赫伯特·迪斯,以及大众管理委员会的一名成员。 “文德恩承认,”他的律师在美国法律文件中写道,“2015年7月27日,也就是关于损坏和产品问题的例行会议之后,文德恩、迪斯和其他大众汽车公司人员参加了一个非正式会议,专门讨论了2016年款柴油车的销售许可问题。”然而,律师格雷戈里·约瑟夫继续说道,“文德恩拒绝承认2015年9月之前就知道柴油车排放问题的起因或严重性。” 迄今为止,大众对7月27日会议的态度一直模棱两可,也拒绝为本文发表关于该会议的评论。 “个别员工在有关损坏和产品问题的例行会议之外讨论过柴油问题,” 2016年3月大众发布的新闻稿中称。这份新闻稿也是大众对这一问题的最后一次、最彻底的公开讨论。 “目前尚不清楚参与者当时是否明白软件调整违反了美国的环境法规。文德恩已经要求公司对此问题进行进一步澄清。“(2月下旬大众可能会在向德国证券诉讼中提交的文件中详细介绍公司对此次会议的看法,不过这些文件并不对外公开。) 大众对美国监管机构撒谎一直持续到8月19日,最终一位工程师向加州空气资源委员会承认了作弊行为。当月晚些时候,在事情进展情况传到狼堡后,一位内部高级律师通知员工,公司将于9月1日将采取“诉讼保全措施”,在此之后员工不得销毁相关文件。约有40名大众工程师认为这份通知是命令他们立刻删除文件。有人通知了博世的工程师,后来博世工程师也销毁了文件资料。 大众高层明显感觉到麻烦来了。8月,他们让美国凯易律师事务所调查了使用作弊装置可能需承担的监管责任。律师事务所的回复令人欣慰:2014年,违反《清洁空气法案》最高罚款金额仅为1亿美元,涉及110万辆汽车,而当时大众已知的可能涉案车辆还不到这个数字的一半。 但两起事件几乎没什么可比性。在之前的案件中,现代起亚被指夸大了每加仑燃油经济性,较实际夸大了1到6英里,但现代起亚拒绝承认,因为起亚使用了最理想情况下获得的测试数据,而不是大量测试后的平均值。涉案车辆的排放量并无超标情况,不需要召回,也没有对监管机构撒谎。 凯易律师事务所在备忘录中称,律师并不知道十年来大众一直在向监管机构撒谎。律师还曾敦促大众去核实自己向监管机构递交的声明是否“完整无误”。由于缺乏信息,备忘录得出的结论是“目前尚未发现任何事实证明存在(犯罪)问题。” (对于询问备忘录的电话和电子邮件,凯易律师事务所没有回复。原告律师迈克尔·梅尔克森代表柴油车主提起诉讼时也将备忘录纳入了诉讼文件当中。这时,备忘录已经公开。柴油车主后来放弃了联邦集体诉讼)。 2015年9月3日,大众一名主管在下属口头承认后,以书面形式向加州空气资源委员会正式承认使用作弊装置。大众承认,文德恩在第二天便已得知此事。尽管德国法律要求立即披露重大的市场信息,但大众股东并没有获知此事。9月18日,当加州空气资源委员会和美国环保署公布这一举世震惊的消息时,股东们才知道大众已承认在美国销售的近500,000辆2.0升汽车上安装了非法作弊装置。美国司法部次日宣布启动刑事调查。三天后,大众宣布全球约有1100万辆汽车安装了美国监管机构发现的双模式软件。大众股票市值在一周的时间内蒸发了约325亿欧元(按现在的汇率计算约为385亿美元)。随后的几个月里,大众市值缩水规模升至约556亿欧元(约合660亿美元)。 大众认为,公司在2015年9月美国监管机构宣布发布“违规通知”前没有义务透露任何信息。“大众认为,公司已根据资本市场法规履行了披露义务”,大众在发给ProPublica的书面声明中称。“违规通知发送之前,管理委员会根据美国外部法律顾问和众多判例认为,大众仍有可能就这一问题的解决办法与美国监管机构达成共识。” 随着排放门调查的缓慢进行,2017年夏天,业界出人意料地爆出了一个更大的阴谋。德国《明镜周刊》报道称,1999年以来,德国五大汽车制造商——奥迪、宝马、戴姆勒(梅赛德斯-奔驰制造商)、保时捷和大众一直互相勾结,这一行为可能违反了竞争法。(拥有其中三个品牌的大众和戴姆勒已经向欧盟竞争主管部门承认,可能进行过一些不当的讨论;宝马则坚持认为自己一直都在合法经营。) 各方举行过1000多场会议,涉及60个工作组,涵盖汽车生产的各个方面,也包括排放控制。据该杂志报道,排放小组早在2007年就开始谋划用于控制某些柴油机NOx排放的排气设备规格。这项新丑闻可能会连累大众高管,使其接受更多的调查,但也有可能减轻他们的痛苦,因为这意味着业界都是一丘之貉。 2018年初,有损德国汽车制造商形象的消息接二连三地传来。纪录片制作人亚历克斯·吉布尼和《纽约时报》称,大众等制造商资助的研究机构在2014年曾用猴子测试柴油废气。据称测试车辆是当前所谓的大众清洁柴油车和老款福特柴油卡车,分别在实验室的滚筒上进行了测试,以便对比测试效果。该消息传出后,大众首席执行官穆勒写信给员工,称这些测试“不道德,令人反感且非常可耻”,并为“参与者的判断失误”道歉。穆勒表示正在调查并“一定会给出解释”。猴子测试事件曝光后,大众股价出现下跌。但相对一直回升的股价来说只是个小波动而已:现在的股价刚刚超过了排放门曝光时的水平。 詹姆斯·梁和奥利弗·施密特,可能最终还有帕米奥,有可能成为柴油门事件美国仅有的三位责任承担人。虽然2006年欺诈事件刚开始时梁还在狼堡工作,但他于2008年被调往加利福尼亚州洛杉矶西部的大众奥克斯纳德测试中心,协助启动清洁柴油计划。2015年10月,当联邦调查局到访其在纽伯里公园附近富人区的住处时,他仍在测试中心工作。 政府称,梁十分合作。梁今年63岁,在大众已工作34年,性格温和,家中有妻子和三个孩子。他没当过主管,但由于自始至终参与了欺诈,科克斯法官判处了40个月的监禁,比检方要求的刑期更长。 施密特没必要去美国,他的举动相当鲁莽。2015年11月,他在没有寻求律师意见的情况下就联系了FBI特工,协助进行调查。联邦调查局让他从狼堡飞到伦敦,并进行了会面。美国检方也飞去伦敦与他见面。但特工和检察官后来认定,施密特在五小时的会面中谎话连篇,为自己和上司开脱责任,妨碍了进一步的调查。 施密特显然以为,自己跟美国政府的关系还不错。2016年12月,施密特让其在美国的律师通知联邦调查局,夫妻二人当月晚些时候会去佛罗里达州度假。(他在佛罗里达州有一些租赁物业,还希望在那里过退休生活。)2017年1月7日,就在二人返德途中,八名警察在迈阿密国际机场的男厕里逮捕了施密特。他戴着手铐走出了男厕,随后被带离机场,而他妻子则坐在一堆行李中抽泣不已。 如果施密特留在德国,他或其他主管不一定会受到德国检方的起诉,更不可能获刑七年。研究企业犯罪的德国法学教授(奥格斯堡大学的迈克尔·库比希尔和柏林自由大学的莫森)表示,其中一个可能的指控可能是虚假广告,但较为狭义,并不一定适用,因为它主要针对不公平竞争,且最长刑罚为两年。(莫森与一家为大众员工提供法律服务的律所有关联,但他表示自己并没有参与本案。) 在德国,相关欺诈法一般是用于惩罚骗取他人钱财的人。 “欺诈行为要求个人消费者举证自己的财务确实出现损失,” 库比希尔在一封电子邮件中写道, “即便存在这一可能性,但要证明操纵柴油车排放的确会导致财务损失并不容易。” “你得弄清楚,”莫森在接受采访时说道,“如果用美元或欧元计算,损失是多少?”算起来很难,因为这些汽车适合在道路上行驶而且很安全。我们无法得知的是,法官是否会考虑,由于汽车排放污染超过了消费者的认知程度,法律会认可由此而造成的财务损失。大众曾围绕其欧洲民事责任向ProPublica发布了声明,并在其中指出,“客户满意度是我们最优先考虑的事情,我们为欧洲客户改装的部件不会影响性能、燃油经济性或其他关键指标,这一点已经得到了监管机构的证实。” 确实,根据媒体统计以及对三位欧洲案件原告律师的采访,德国已有数十起消费者诉讼,大部分案件似乎都以大众获胜告终。即使法官裁定大众非法使用欺诈软件,很多人仍认为消费者没有遭受到任何应予以补偿的损失。 剩下的有约束力的刑法就是禁止市场操纵的法规。大众高管在向市场披露公司所出现的危机时似乎显得特别迟钝,但其中也存在障碍。例如,高管可以引述凯易律师事务所的报告,该报告预测可能存在1亿美元的轻罚,而且他们也可以称这一金额并没达到“重大”水平,所以没必要向公众披露。 或许,德国检方最终能克服种种困难,给大众定一些罪名。奥利弗·施密特也许会在这一方面提供帮助。在判决宣布前,施密特给科克斯法官写了一封信,信中称,自己“在狱中的很多不眠之夜里”一直在仔细研究政府列举的大众造假证据。施密特写道,“我发现,虽然我的上级曾对我说他们在我发现造假问题之前并没有参与这一事件,但他们其实在很多,很多年前便已知晓这一问题。我真的感觉被自己的公司给耍了。”(财富中文网) 补充报道由杰西·艾辛格撰写 译者:冯丰 审校:夏林 |

In Wolfsburg, VW engineers, led by Neusser, Gottweis, and others formed an ad hoc committee to address the study. Their goal, according to prosecutors, was to concoct evasive and misleading responses to regulators’ anticipated questions. On May 23, 2014, Gottweis wrote a now infamous report about the West Virginia study, which Tuch forwarded to Winterkorn the same day, as part of his regular weekend package of reading materials. (VW suspended Tuch in October 2015, and he resigned in February 2016. He could not be reached for comment.) The memo, revealed by Bild Am Sonntag in 2016, has been regarded as a smoking gun by Winterkorn’s critics. “A thorough explanation for the dramatic increase in NOx emissions cannot be given to the authorities,” Gottweis wrote. “It can be assumed that authorities will then investigate” to see if VW used a “defeat device,” he continued, explaining what a defeat device was. A team is working on software changes that can “reduce the real driving emissions,” he noted, “but this will not bring about compliance with the limits either.” For its part, Volkswagen asserts that nothing in the Gottweis report should have caused its CEO to suspect that anything more than a routine product defect was afoot. “This memo merely raised the prospect that U.S. regulators would investigate whether a defeat device was in use,” the company’s lawyers wrote in its motion to dismiss U.S. shareholder litigation in August 2016; “it did not state or imply that a defeat device had actually been installed, or what it meant if a defeat device were found by U.S. authorities, much less the potential magnitude of any associated financial risks resulting from such a finding.” Winterkorn admits receiving the report, according to papers his attorney filed in U.S. civil litigation, “but does not recall whether he read [it] that weekend.” He also admits being aware of the West Virginia University study by May 2014 — 15 months before the conspiracy ended — but says, according to the same filing, that “he believed a task force of Volkswagen employees were working to address the situation.” One was. At its behest, VW engineers, including Liang, lied to CARB and EPA regulators for more than a year. They even promised regulators that they’d address the problem with a software fix, carried out through yet another recall in late 2014. In November, Winterkorn was advised of this recall in a one-page memo that estimates the fix would cost just €20 million to effectuate — a negligible sum for a company whose 2014 net operating profit would come to €12.7 billion. Winterkorn, in his testimony before the German Parliament, said the memo reassured him that the problem had been addressed. But by early 2015 CARB had discovered that the recalled vehicles still exceeded NOx limits during real-world driving. By that time, Oliver Schmidt, who’d been at VW’s environmental office in Auburn Hills, Michigan for three years, had been promoted. In February 2015 he had returned to Wolfsburg to become one of three deputies to Neusser, who, by then, had become chief of development for the VW Brand, overseeing 10,000 employees. In July, CARB told VW engineers that it would refuse to certify the company’s 2016 diesels until it got better answers. That precipitated the July 27, 2015, meeting at which Schmidt and a colleague made their presentations to Winterkorn and other top executives, including Herbert Diess, then and now the highest executive in charge of its VW brand passenger car unit, and a member of VW’s management board. “Winterkorn admits,” his attorney wrote in a U.S. legal filing, “that on July 27, 2015, after a regular meeting about damage and product issues, he, Diess, and other VW AG personnel participated in an informal meeting during which there was a discussion regarding approval for the sale of model year 2016 diesel vehicles.” However, the attorney, Gregory Joseph, continues, “Winterkorn denies that he knew the cause or significance of the issues related to diesel emissions before September 2015.” To date, the company has been vague and noncommittal about the July 27 meeting, and it declined to comment on it for this article. “Individual employees discussed the diesel issue on the periphery of a regular meeting about damage and product issues,” the company said in a March 2016 press release, its last and fullest public discussion of matter. “It is not clear whether the participants understood already at this point in time that the change in the software violated U.S. environmental regulations. Mr. Winterkorn asked for further clarification of the issue.” (The company is expected to describe its perspective on the meeting more fully in late February in a filing in German securities litigation, though such filings are not public.) The lying to US regulators continued until August 19, when an engineer confessed to CARB regulators. Later that month, after word of this development reached Wolfsburg, a high-level in-house attorney notified employees that a “litigation hold” would be issued on September 1, after which they not be permitted to destroy pertinent documents. About 40 Volkswagen engineers took this as a directive to start deleting immediately. Some notified Bosch engineers, who did the same. Top VW officials clearly sensed trouble. By August they had asked the American law firm Kirkland & Ellis to look into possible regulatory liability for use of a defeat device. VW received the reassuring news that the largest fine that had ever been meted out for a Clean Air Act violation had been just $100 million, in 2014, for an incident involving 1.1 million cars — more than twice as many vehicles as were then known to be implicated in VW’s Clean Diesel problems. Yet the incident being used as a benchmark was hardly similar. In that instance, Hyundai-Kia, which never admitted wrongdoing, had overstated fuel economy by 1 to 6 miles per gallon because it used figures obtained in the most favorable tests it had run, rather than by averaging results from a large number of tests. But the cars’ emissions were never illegal, no recalls were required, and no lying to regulators had been alleged. The text of the Kirkland memo suggests that the lawyers hadn’t been informed that the company had been lying to regulators for a decade. The lawyers urged VW to find out if statements made to regulators had been “complete and not misleading.” Given the lack of information, the memo concluded that “we are currently unaware of any facts that suggest any such [criminal] issues in the present situation.” (Kirkland & Ellis did not return calls and emails seeking comment on the memo, which became public when plaintiffs lawyer Michael Melkerson filed it in a lawsuit on behalf of diesel owners who opted out of the Federal class action.) On Sept. 3, 2015, a VW supervisor confessed to CARB in writing the use of a defeat device, formalizing his subordinate’s earlier oral admission. Winterkorn was notified the next day, VW has acknowledged. Still, despite German laws requiring that material market information be disclosed immediately, VW shareholders were given no inkling that anything was amiss. They learned only when CARB and EPA stunned the world on September 18 with the news that the company had admitted using an illegal defeat device on close to 500,000 2.0 liter cars sold in the U.S. The Justice Department announced a criminal investigation the next day. Three days after that VW revealed that some 11 million cars worldwide were equipped with the dual-mode software that the U.S. regulators had discovered. Over that week, the company’s shares lost about €32.5 billion in value ($38.5 billion at today’s rates). In the ensuing months, the total decline ballooned to about €55.6 billion ($66 billion). Volkswagen argues that it had no obligation to disclose anything until U.S. regulators announced they were issuing a “notice of violation” in September 2015. “Volkswagen believes that it duly fulfilled its disclosure obligation under capital markets laws,” the company asserted in a written statement for ProPublica. “Right up until the publication of the notice of violation, the board of management believed, based on the advice of its U.S. external legal counsel and numerous precedents, that Volkswagen could resolve the issue consensually with U.S. regulators.” As the Dieselgate investigation slowly churned, allegations of a much vaster conspiracy unexpectedly emerged this summer. Der Spiegel reported then that since 1999 all five German carmakers — Audi, BMW, Daimler (which makes Mercedes-Benz cars), Porsche, and Volkswagen — had been colluding in ways that may have violated competition laws. (VW, which owns three of the brands, and Daimler have admitted to EC competition authorities that some discussions might have been improper; BMW maintains they were lawful.) The participants held more than 1,000 meetings relating to 60 working groups on different aspects of automotive production, including emissions control. As early as 2007, according to the magazine, the emissions group began colluding on specifications for exhaust equipment that was used to control NOx emissions in some of the diesel engines. This new scandal could hurt VW executives by bringing even more scrutiny to their actions — or help them by suggesting every car company was doing the same thing. In early 2018 came yet more news that sullied German automakers, as documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney and the New York Times reported that research organizations funded by those manufacturers — including VW — had, in 2014, gassed monkeys with diesel exhaust fumes from a modern-day, allegedly Clean Diesel VW and an old Ford diesel pickup truck, each running on rollers in a lab, in order to show their relative effects. When the news broke in January, VW CEO Müller wrote to employees, calling the tests “unethical, repulsive and deeply shameful” and apologizing for “the poor judgment of individuals who were involved.” The CEO said the company is investigating and “we will be coming to all the necessary conclusions.” VW’s stock price fell when the reports of the monkey tests emerged. But that was a minor bump in a resurgence of the company’s shares: They’re now priced just above where they were when Dieselgate was revealed. That James Liang and Oliver Schmidt — and perhaps eventually Pamio — would end up being the only ones to take the fall for Dieselgate in the United States is happenstance. Though Liang was working in Wolfsburg when the conspiracy began in 2006, he was transferred in 2008 to VW’s Oxnard, Calif., test center, west of Los Angeles, to help with the Clean Diesel launch. He was still working there in October 2015 when the FBI knocked on his door in the nearby affluent community of Newberry Park. Liang began cooperating immediately, according to the government. A slight, mild-mannered man with a wife and three children, Liang, now 63, had worked for VW for 34 years. He was never a supervisor. Still, because of his long involvement in the scheme — from start to finish — Judge Cox sentenced him last August to 40 months in prison, a lengthier term than prosecutors had requested. Schmidt’s presence in the United States was unnecessary, even reckless. Acting without counsel, he contacted FBI agents in November 2015, offering aid with their investigation. The FBI flew him from Wolfsburg to London to meet with him there. U.S. prosecutors flew there, too, to participate. But the agents and prosecutors later determined that Schmidt lied extensively at the five-hour debriefing, falsely exonerating himself and his superiors, and setting back their probe. Evidently imagining that he was still on good terms with the government, in December 2016 Schmidt had his U.S. lawyer notify the FBI that he and his wife would be travelling to Florida later that month for their annual Christmas vacation. (He owned some rental properties in Florida, and had hoped to retire there.) On January 7, 2017, as they headed home to Germany, eight officers converged on Schmidt in a men’s room at the Miami International Airport. They brought him out in shackles and then led him away. His wife was left alone, crying amid a pile of luggage. Had Schmidt remained in Germany, it’s unclear whether he or other supervisors could have been charged under German law, and it’s inconceivable that the result would’ve been a seven-year sentence. One possible charge could have been false advertising, but that is narrow, not necessarily apt — it is aimed primarily at unfair competition — and carries a two-year maximum term, according to two German law professors who have studied corporate crimes: Michael Kubiciel, of the University of Augsburg, and Momsen of Berlin’s Free University. (Momsen is associated with a law firm that represents a VW employee in the inquiry, but says he is not personally working on that case.) The relevant German fraud statute, in turn, is generally designed to capture individuals who swindle others out of money. “Fraud requires proof of a concrete financial loss on the part of an individual consumer,” writes Kubiciel in an email. “Proving that a manipulation of the diesel engine caused concrete financial damage is not easy, if possible.” “You need to be able to figure out,” says Momsen in an interview, “what is the damage in dollars or euros?” That’s challenging, he continues, because the cars were roadworthy and safe. It’s not clear whether German judges will consider the fact that a vehicle was polluting more than the consumer realized to constitute the sort of financial damage the law recognizes. As VW put it in its statement to ProPublica concerning its civil liability in Europe, “Customer satisfaction is our highest priority and the modification we have provided our customers in Europe entails no change to performance, fuel economy or other key vehicle attributes, as confirmed by our regulator.” Indeed, scores of consumer lawsuits have been tried in Germany and Volkswagen appears to be winning most of them, according to newspaper accounts and interviews with three European plaintiffs lawyers. Even when judges have ruled that VW used an illegal defeat device, many have still concluded that consumers suffered no compensable injury. The main remaining criminal statute in play is the one barring market manipulation. VW executives might appear to have been astoundingly tardy in notifying the market of the building crisis at their company. Yet there are hurdles here, too. Executives can point, for instance, to the Kirkland & Ellis report — predicting modest sanctions in the vicinity of $100 million — and argue that that didn’t sound like a “material” loss that needed to be disclosed. Perhaps, despite the many daunting obstacles, German prosecutors will yet manage to obtain some convictions. It sounds as if Oliver Schmidt will be rooting for them. In a letter to Judge Cox before his sentencing, he described how he had pored over the government’s VW evidence “during my many sleepless nights in my prison cell.” As Schmidt put it, “I’ve learned that my superiors that claimed to me to have not been involved earlier than me at VW knew about this for many, many years. I must say that I feel misused by my own company.” This article is a collaboration between Fortune and ProPublica, a nonprofit investigative news organization. Additional reporting by Jesse Eisinger |