《财富》揭秘:美国政府囤积了多少比特币

|

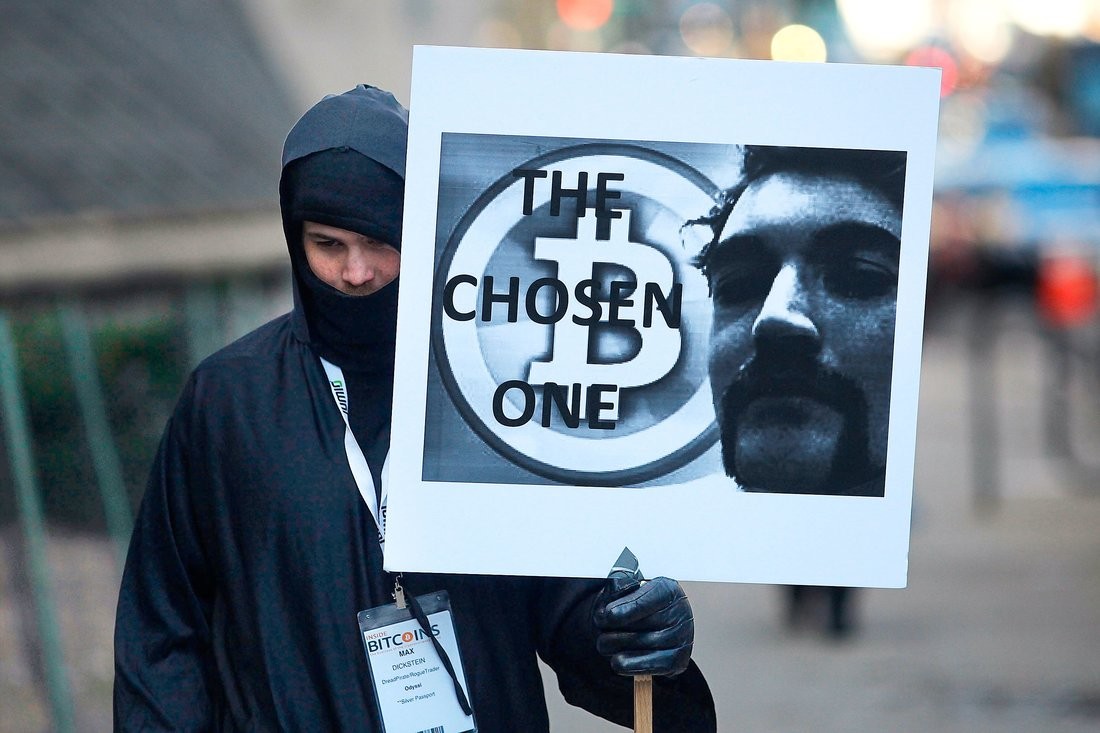

去年7月,25岁的亚历山大·卡兹在泰国一家监狱自缢身亡,身后留下了堪比顶级毒贩的财物:别墅、兰博基尼、保时捷、列支敦士登和瑞士的银行账户。官方表示,卡兹是全球最大的毒品和武器黑市网站阿尔法湾(AlphaBay)的运营者。他还留下了另一样东西:装有价值数百万美元的比特币及其他虚拟货币的电子“钱包”。 美国司法部在一次全球突击行动中缴获了卡兹的虚拟财产,它们现在归该部所有,司法部计划将其出售。比特币的价格自缴获时到现在,已经猛涨了原来的5倍有余,司法部将获益丰厚。不过如果想要知道比特币的持有者是谁,或它何时被交易,必须具备强大的网络侦查技能,以及大量的空闲时间。 数字货币的收缴和销售,在五年前还鲜为人知,而今正快速成为普通事物。比特币长期以来深受网络罪犯喜爱,现在也越来越多地出现在刑事搜捕案件当中,它使得美国成为了加密货币市场的主要参与者。我们无法得知确切的数字,不过根据书面证据和对现任及前任辩护律师和检察官的采访,可以推算出美国执法部门至少保管着价值10亿美元的数字货币,并且实际金额很可能要远高于此。 数字货币一旦进入政府手中,便蒙上了神秘的面纱。比特币的匿名性让它广受自由论者喜爱,不过加上这些自由论者所痛恨的不透明的财产没收法律,公众几乎不可能追踪数字货币流向。联邦机构为加密货币的繁荣发挥着日趋重要的作用,他们为守护手中的数字黄金做出了令人讶异的举动,乃至犯下错误或者犯罪。 美国法警局(U.S. Marshals Service)是美国历史最为悠久的执法部门,枪手怀特·厄普和“狂野比尔”希科克都曾是它的成员。最近,电视和电影作品让许多美国人了解到它如何运送囚犯及追踪危险逃犯,不过很少有人知道,法警局还出售比特币。 根据拥有几十年历史的一条法律规定,法警局这个隶属于美国司法部的机构,有一项主要职责是处理其它联邦执法机构缴获的物品,这也是为什么访问法警局网站可以看到被联邦调查局和其他机构收缴的船只、汽车、飞机、手表等非法财物,这些物品全都参加公开拍卖。20世纪80年代,国会的一项决议让联邦官员能更容易地出售毒品犯罪相关财物,此后没收财物程序(见边栏)变得更为普遍,也更具争议性。 那时,没有人知道将来这些财产当中还会包括在电脑上挖矿获得的金钱。这种认知在前几年对丝绸之路(Silk Road)的大规模调查中就已产生改变。丝绸之路是一家类似eBay的全球性非法毒品销售网站。一位来自德克萨斯州的年轻人恐怖海盗罗伯茨(真名:罗斯·乌布利希),利用三项当时的新技术建造了丝绸之路网站。它们分别是廉价的云数据存储;允许用户隐秘游览网络世界黑暗深处的洋葱浏览器;以及允许用户不通过银行,以安全、半匿名方式相互支付的比特币。 |

When Alexandre Cazes hanged himself in a Thai jail cell in July, the 25-year-old left behind the trappings of a big-league drug dealer: villas, Lamborghinis, a Porsche, bank accounts in Liechtenstein and Switzerland. But Cazes, who authorities allege operated AlphaBay, the world’s largest black-market website for drugs and weapons, also left something else: Internet “wallets” holding millions of dollars’ worth of Bitcoin and other virtual currencies. Cazes’s digital loot is now property of the U.S. Justice Department, which seized it during a global sting operation. The agency plans to sell it, and given that Bitcoin’s value has soared more than fivefold since then, it could reap a huge windfall. But if you want to find out who’s holding those coins, or when they’re being sold, you’ll need extensive cybersleuthing skills—and a lot of free time. These digital seizures and sales, unheard-of five years ago, are fast becoming routine. Bitcoin’s enduring popularity among online wrongdoers, and its growing presence in criminal busts, has turned Uncle Sam into a major player in cryptocurrency markets. While exact figures are impossible to pin down, documentary evidence and interviews with current and former defense attorneys and prosecutors suggest that at least $1 billion worth of digital coins, and possibly much more, has spent time in the custody of U.S. law enforcement. But once in government hands, this digital hoard disappears behind a cloak of secrecy. The anonymity that makes Bitcoin a darling of libertarians—along with opaque property-seizure laws hated by those same libertarians—makes it virtually impossible for the public to follow the digital money. And as federal agencies have been drawn into an ever-growing role in the cryptocurrency boom, their efforts to guard their digital gold have led to surprises, stumbles, and sometimes sin. The U.S. Marshals Service is the oldest law-enforcement agency in the country, counting gunslingers like Wyatt Earp and Wild Bill Hickok among its alumni. More recently, TV and movies have familiarized many Americans with its role transporting prisoners and tracking dangerous fugitives. Far fewer people know the marshals sell Bitcoin. A decades-old law gives the Marshals Service, which is part of the Department of Justice, primary responsibility for disposing of items seized by other federal law-enforcement agencies. That’s why you can visit the marshals’ website and ogle boats, cars, planes, wristwatches, and other ill-gotten gains snatched by the FBI and other agencies, all available at public auction. The seizure process, known as forfeiture (see sidebar), became more commonplace and controversial in the 1980s after Congress made it easier for federal officials to sell assets tied to drug crimes. At the time, no one knew these assets would someday include money mined on computers. That changed earlier this decade during an epic investigation into Silk Road—a global eBay for illegal drugs. A young Texan known as Dread Pirate Roberts (real name: Ross Ulbricht) built Silk Road on three then-new technologies: cheap cloud data storage; the Tor browser, which let people roam dark parts of the Internet undetected; and Bitcoin, which let them pay each other in a secure, semi-anonymous manner, without involving banks. |

|

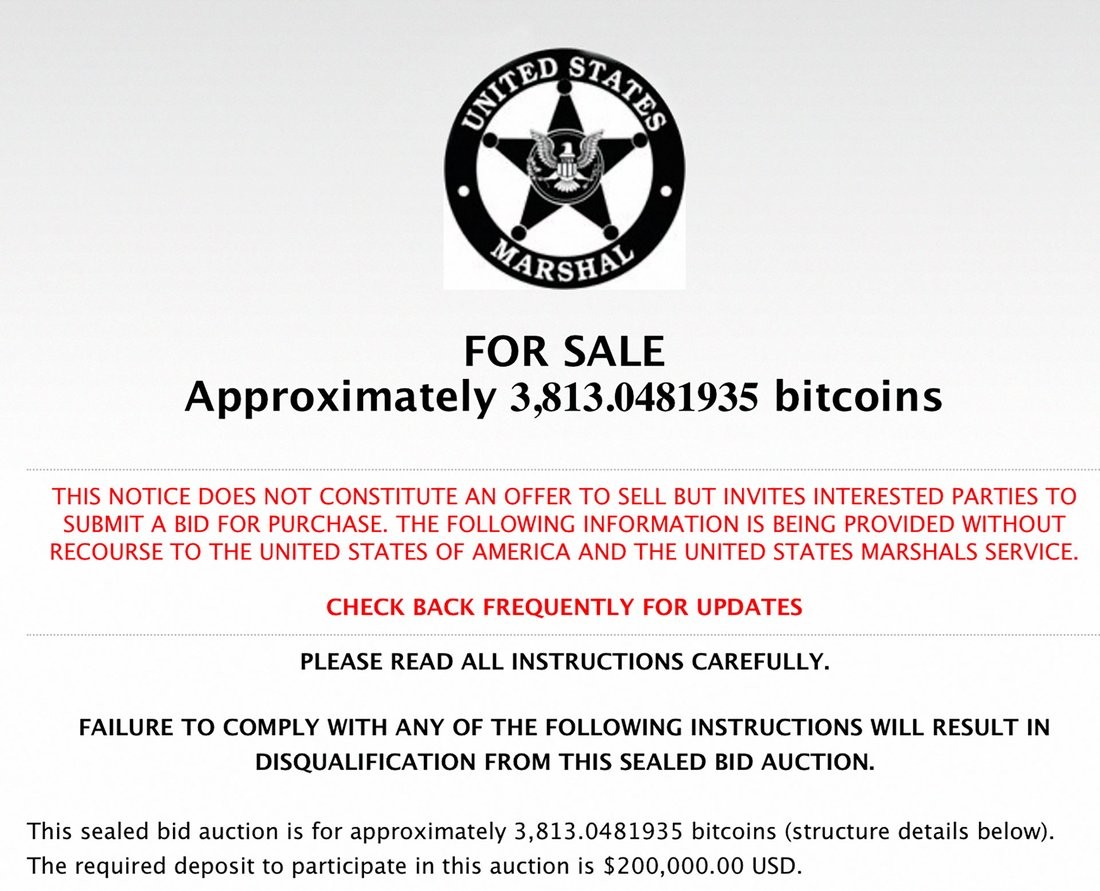

2013年联邦政府查封丝绸之路网站时,罪犯们已经精通比特币,但执法部门未及时跟上。参与该案的一位检察官说:“对此没有任何专业知识,它实在是太新了。”恐怖海盗跟当时(及现在的多数罪犯)大部分精明的比特币用户一样,并不依赖于Coinbase这样的中介来持有数字货币。乌布利希利用私人密钥——一长串几乎不可能破解的字符——来控制他的电子钱包。执法部门想要获取设有私人密钥的比特币,唯一的方式就是嫌犯泄露密钥信息。不甘放弃的特工们想出了在嫌犯货币未受保护时进行缴获的方法。为得到乌布利希的比特币,他们在旧金山图书馆逮捕他时,当他的面夺走他开着机且未上锁的笔记本电脑。(卡兹一案中,特工们开车迅速进入他在泰国的住处时,他正在使用阿尔法湾的管理员账号登陆。)到抓捕恐怖海盗时,法警局的效率已大幅提升。他们控制着至少两个自己的电子钱包,用于存储丝绸之路的货币,接收其他部门缴获的比特币。曾长期担任纽约南区联邦检察官办公室资产没收部主任,目前为威凯律师事务所(WilmerHale)合伙人的莎朗·科恩·莱文说:“这是一项前沿技术,我们从未这样做过。”缴获数字货币之后,法警局回归常规程序,将它与可卡因走私贩的快艇以同样方式处置:拍卖。这是一项挑战巨大的任务,因为缴获的货币数值巨大,大约有17.5万枚,占当时所有流通比特币的2%。根据熟悉案件的检察官所言,法警局采取了交错拍卖的方式,以防比特币价值暴跌。2014年6月至2015年11月期间举行的四次拍卖中,法警局以每枚均价379美元售出了丝绸之路比特币。比特币价在此后一路飙升。今年1月的另一场拍卖中,法警局售出3,813枚比特币,净赚4,500万美元,每枚比特币的价值高达约1,1800美元。按照这样的价格,法警局出售囤积的丝绸之路数字货币本可赚取21亿美元,足以支付法警局的年度预算,但在2014和2015年,它只净赚了6600万美元。与此同时,身价亿万的风险投资家蒂姆·德雷珀以每枚约600美元的价格买下了3万枚丝绸之路网站的比特币,这或许是他这十年来最佳的投资。德雷珀对《财富》杂志说,拍卖过程“十分顺利”,而且他一枚也没卖出。他补充道:“为什么我要用过去交换未来呢?” |

By 2013, as the feds closed in on Silk Road, criminals had become savvy about Bitcoin, but law enforcement lagged behind. “There was no expertise. It was too new,” says a prosecutor involved in the case. Like most sophisticated Bitcoin users at the time (and most criminals today) the Dread Pirate didn’t rely on a broker such as Coinbase to hold his digital funds. Instead, Ulbricht controlled an online wallet using a private key—a long, complex set of characters that’s basically impossible to guess. In private-key cases, the only way law enforcement can quickly obtain the Bitcoin is if the suspect reveals the key.Enterprising agents figured out ways to snag suspects’ currency when it wasn’t protected. To get Ulbricht’s Bitcoin, they snatched his open, unlocked laptop from under his nose while arresting him in a San Francisco library. (As for Cazes, he was logged in to an AlphaBay administrator’s account when agents rammed a car through the gate of his Thailand estate.) By the time they busted the Dread Pirate, the marshals had got up to speed: They controlled at least two digital wallets of their own, to hold the Silk Road currency and receive Bitcoins seized by other agencies. “This was cutting-edge stuff,” says Sharon Cohen Levin, a longtime chief of the asset-forfeiture unit in the U.S. Attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York, and now a partner at WilmerHale. “We’d never done something like this.” Once they did, however, the marshals fell back on standard procedure, preparing to handle the Bitcoin the same way they would a coke smuggler’s speedboat: by auctioning it off. That posed challenges because of the sheer size of the seizure—about 175,000 Bitcoins, or 2% of all the Bitcoin in circulation at the time. According to a prosecutor familiar with the case, the marshals opted for a staggered series of auctions to avoid crashing Bitcoin’s price.In four auctions between June 2014 and November 2015, the marshals sold the Silk Road Bitcoins for an average price of $379. Bitcoin went on to enjoy a huge run-up; as a point of comparison, in an unrelated auction this January, the marshals sold off 3,813 Bitcoins and netted $45 million—or about $11,800 per coin.Sold at those prices, the Silk Road stash could have reaped $2.1 billion, enough to cover the Marshals Service’s annual budget; in 2014 and 2015, it netted just $66 million. Billionaire venture capitalist Tim Draper, meanwhile, made what might be the investment of the decade when he snapped up 30,000 of the Silk Road coins for about $600 each.Draper, who described the auction process to Fortune as “smooth,” says he hasn’t sold a single one, adding, “Why would I trade the future for the past?” |

|

法警局当然无法预料到这点。前任检察官、目前在高盖茨律师事务所(K&L Gates)工作的克利福德·司特德说,联邦特工出售资产时,不太可能算准市场时机。讲及自己曾参与的没收证券案件,司特德说:“我们发现政府无意预测股市行情。” 丝绸之路比特币的低价拍卖使得联邦政府受到加密货币爱好者的嘲讽,而在预算吃紧的背景下,高价出售货币的压力骤增。去年11月中旬,比特币的价格达到近2万美元,美国司法官员迅速找到犹他州的联邦法庭,请求允许拍卖他们从仿冒药品销售商手中缴获的513枚比特币。法官批准了该请求,但法警局直到1月末才进行拍卖,此时比特币已跌至最高价的一半左右。 地方当局也面临类似的棘手问题。曼哈顿区检察官办公室网络部门负责人布伦达·费舍尔说:“我们这儿发生了一起传统绑架和抢劫案件。罪犯把受害人引诱到他以为是优步车的车内,用枪指着他,要他拿出价值180万美元的[数字货币]以太币,最终迫使他给出私人密钥。”地区检察官办公室成功追回资金,却遇到一个难题:劫匪将以太币转换成了比特币,比特币的价值在盗窃案后大幅上涨,由此引发新的法律问题:谁该得到这部分盈余呢? 由司法部运营的网站Forfeiture.gov乍看之下对监督部门而言可谓是天赐佳物。最近的某个星期一,主页的一份文件详细列举了由多个部门没收而来、价值至少200万美元的数字货币。从中可以看到,缉毒局从新罕布什尔州的一名毒贩手中没收140枚比特币,从波士顿的一名毒贩手里没收25枚比特币;海关和边境保护局则在盐湖城缴获99枚比特币和99单位的比特币现金(另一种货币)。 但这种信息透明转瞬即逝。从物品被没收直到它出现在报告里,中间往往有较长的滞后,而且报告不会在线存档。每天,新报告一出现,旧报告便消失。纸质副本确实存在,不过不管任何时候,无论在网上或是书面材料上,都无法查到联邦政府保管加密货币的记录。 曾为客户提供没收财物相关建议的美亚博律师事务所(Mayer Brown)律师亚历克斯·拉卡托斯说:“美国有一点很奇怪,就是它缺少中央登记。”。他补充道:“不管是联邦调查局还是地方当局采取的行动,我们都不知道被没收的财产有多少。”当被问及是否有没收财产的公共登记处时,法警局发言人明确回答说没有。而且,法律并未规定政府有义务创建这样的登记处。司特德和其他执法部门人员基本都支持这种不透明性,他们辩解道,提高透明度,可能会向罪犯泄露特工的工作方法,或正在进行的调查。 从理论上来说,联邦政府手中的任何比特币都是可以追踪的,因为加密货币的交易永久记录在公共区块链分类帐上。虽然司法部文件有时会公开识别“安全的政府钱包”,但许多刑事案件并没有,这使得比特币的去向不明。即便在钱包可以识别的情况下,它的内容在外行人眼中似乎只是无穷无尽的字符串——它们实际上代表着匿名的个人货币、交易和用户。可以肯定的是,包括Elliptic和Chainalytic等取证公司在内的行业正在不断兴起,帮助客户将钱包与所有者联系起来,它们的客户当中许多是执法机构。不过,公共信息披露不属于这些公司的业务范围。 这种状况导致人们几乎无法确定政府到底拥有多少加密货币,加之有权缴获比特币的机构众多(其中还有特勤局、酒精、烟草和火器管理局、邮局),政府本身也难以确定所没收加密货币的规模。其实,只要区块链技术部署到位,很容易就能知道货币数额,这点令支持提高透明度的人尤为恼怒。没收的批评者认为,比特币黑洞是以数字化方式展示了被滥用长达数十年的系统。反对者认为,州和地方机构拥有强大的没收权力,会带来负面作用,甚至可能导致警察抢劫平民。司特德说:“我在执法部门工作了23年,我相信,但凡警察没收现金,总有人从中贪污,我不认为这在比特币身上会有任何不同。” 从这个角度看,公共记录与实际的差距之大足以令人担忧。从法庭记录和没收通知中尝试追踪比特币时,《财富》杂志发现,有几笔比特币的缴获被记录在案,其销售却没有任何记录。例如,2014年的法庭文件显示,美国联邦税务局从德克萨斯州的一位大麻毒贩手中缴获222枚比特币,但没有任何关于销售的文字记录。同样,特勤局2014年从一对在“JumboMonkeyBiscuit”网站经营非法毒品和货币兑换的夫妇手中缴获50.44枚比特币,也没有拍卖记录。(其他一些案例中的货币估值也相当古怪——例如,2月初盐湖城缴获99枚比特币的没收通知中,显示其价值为0美元,而实际上它当时价值约有80万美元)。这些货币中的一部分可能被正在进行的案件占用,或还在没收机构手中。由于法警局拒绝就内部程序发表评论,也就无从得知他们是否有正当理由来解释这些比特币的去处。 到目前为止,没有证据表明政府官员利用没收程序漏洞来盗取比特币,前检察官(包括司特德)则强调,腐败是例外,而非全部。尽管如此,没收和出售的长时间间隔无疑增加了辩护律师和公民自由论者的怀疑。所有消息来源都认为,不透明的监督加上数字货币容易转移的特点,很容易就会让执法者误入歧途,联邦调查局的第一次大型比特币抓捕行动证实了这点。 贾罗德·库普曼是美国税务局刑事调查科的网络犯罪主管。税务局打击犯罪部门有大约2,000名特工——持有徽章和枪支的会计师——属于不断壮大的加密货币专家队伍的一部分。库普曼说:“他们是百里挑一的精英。” 这支团队最著名的一次抓捕行动也成为最饱受诟病的一次,原因在于发生了监守自盗。对丝绸之路进行调查期间,美国缉毒局的卡尔·福斯和特勤局的肖恩·布里奇斯疯狂犯罪,就连阿尔·卡彭也会自愧不如。恐怖海盗罗伯茨被捕之前,他们从主犯和他的网站上偷取比特币,并向他勒索财物。这对狡猾的家伙甚至冒充杀手,伪造杀死告密者的场景,企图对乌布利希进行再次欺诈。税务局侦探成功诱捕福斯和布里奇斯,两人都在2015年承认与此案件有关的指控。两位特工的欺诈发生在乌布利希的资产被没收之前,从严格意义上来讲,他们没有影响到没收程序。即便如此,从这起案件中可以看出,在数字货币符合没收相关法律时,也可能会滋生不法行为。 法警局是最适合提供没收财产详细账目的机构,但它的运行本身就不够透明。去年9月,参议院司法委员会工作人员完成漫长的调查之后,委员会主席、参议员查克·格拉斯利(来自爱荷华州)对法警局提出猛烈抨击,指责他们滥用没收的资金,购买诸如“高档花岗岩台面和价格高昂的定制艺术品”等额外福利和奢侈品,其中大部分都地安在了休斯顿新建的资产没收学院,这真是再合适不过了。上述并不算是特大盗窃案件,可它也无法平息没收批评人士或比特币拥护者的怒火。他们中许多人之所以接受比特币,就是因为对政府的诚信缺乏信心。 据库普曼估算,他的税务局团队已经帮助缴获了价值数千万乃至数亿美元的虚拟货币。这仅仅是来自一个机构的数据,美国还有十几个机构拥有没收权。按照库普曼的猜算,我们可以估计美国政府在数字货币市场上的影响力。随着加密货币日趋普遍,这一影响势必将不断扩大。 寻找非法货币的过程仍将挑战重重。前网络犯罪检察官、现怡安集团顾问尤徳·韦勒表示,多年来,坏人们一直在“转向其他没有留下同样数字痕迹的货币。”许多人放弃比特币,转而使用门罗币和零币等,它们同样能够提供安全支付选择,但几乎无法追踪。取证公司Elliptic首席执行官詹姆斯·史密斯表示,越来越多的网络黑市都在发展一项名为Tumbler的技术,它能将交易记录打乱,加进付款服务当中。这等于是一场无穷无尽的虚拟猫和老鼠游戏。如果执法人员自身犯罪,他们偷窃的货币能更容易地隐藏起来。 与此同时,数字货币市场仍在繁荣发展。forfeiture.gov近期发布报告称,缉毒局在新泽西州缴获了6枚比特币,检察官办公室在科罗拉多州一位名叫安东·派克的人身上没收了27枚比特币(价值约33万美元)。据报道,在今年2月初一场针对全球信用卡欺诈集团的突击行动中,美国又净赚超过10万枚比特币。从理论上来说,山姆大叔总有一天会把这些比特币全部拍卖。(财富中文网) 本文的另一个版本刊登于2018年3月份的《财富》,标题为“山姆大叔的比特币小金库”。 译者:严匡正 |

The marshals couldn’t have anticipated this, of course. And federal agents shouldn’t be expected to time the market when they sell assets, says Clifford Histed, a former prosecutor who now practices at K&L Gates. In cases Histed worked in which securities were seized, he says, “we realized the government doesn’t want to be in the business of guessing the stock market.” Still, the Silk Road fire sale exposed the feds to ridicule from cryptocurrency devotees—and in an era of strained budgets, the pressure to sell high is great. In mid--December, as prices neared $20,000, U.S. attorneys rushed to federal court in Utah for permission to sell 513 Bitcoins they’d seized from a seller of counterfeit pharmaceuticals. The judge agreed, but the marshals didn’t make the sale until late January, by which point the price of Bitcoin had fallen nearly 50% off its high. Local authorities are dealing with comparable headaches. “We had a good, old-fashioned kidnapping and robbery where they put the guy into what he thought was an Uber and then held him at gunpoint for $1.8 million worth of [digital currency] Ethereum,” forcing him to give them his private key, says Brenda Fischer, who leads the cyber unit of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office. The DA’s office recovered the funds but is now coping with a conundrum: The robber converted the Ethereum to Bitcoin, whose price rose significantly after the theft—raising novel legal questions over who should get the surplus windfall. Forfeiture.gov, a website run by the Justice Department, might seem at first like a godsend for watchdogs. On a recent Monday, a document on the home page detailed at least $2 million worth of digital coin forfeitures involving multiple agencies. You could learn that the Drug Enforcement Administration took 140 Bitcoins from a drug dealer in New Hampshire and 25 more from one in Boston, and that Customs and Border Protection seized 99 Bitcoins and 99 units of Bitcoin Cash (a separate currency) in Salt Lake City. But the transparency is fleeting. There are often long lag times between the date of a seizure and its appearance in a report. And reports aren’t archived online: Each day, when a new one appears, the old one goes away. Paper copies exist—but nowhere, online or on paper, is there a tally of the cryptocurrency in federal custody at any given time. “This country is weirdly lacking in central registries,” says Alex Lakatos, an attorney with Mayer Brown who has advised clients on forfeiture. Whether it’s the feds or local authorities doing the seizing, he adds, “we don’t know how much property has been seized.”Asked if there is any public registry of forfeited property, a spokesperson for the marshals replies with a flat no. And there is no law obliging the government to create one. Histed and others in law enforcement generally defend this opacity; more transparency, they argue, could tip off criminals about agents’ methods or ongoing investigations. In theory, any Bitcoin in federal hands can be traced, because cryptocurrency transactions are inscribed forever on a public blockchain ledger. But while Justice Department documents sometimes publicly identify “secure government wallets,” many criminal cases do not, making it unclear where the Bitcoin went. Even in cases in which the wallet is identifiable, its contents appear to a layperson as endless strings of alphabet-soup characters—anonymized representations of individual coins, transactions, and users. To be sure, a cottage industry of forensics firms, including Elliptic and Chainalysis, has sprung up to help clients—many of them law-enforcement agencies—connect wallets to their owners. But public disclosure is not part of their mission. This state of affairs makes it extremely difficult to figure out how much cryptocurrency the government owns—and it’s not clear, given the range of agencies grabbing Bitcoin (which also includes the Secret Service; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms; and the Post Office) that the government itself knows. For advocates of transparency, it’s particularly galling given that blockchain technology, if deployed well, could easily make this clear. And to critics of forfeiture, the Bitcoin black hole is a digital manifestation of a system that has been abused for decades. Foes say that sweeping forfeiture powers at the state and local level create perverse incentives that can lead, in effect, to cops robbing civilians. “I’ve spent 23 years in law enforcement and, unfortunately, I believe as long as police have been seizing cash, some have been skimming it,” says Histed. “I don’t think Bitcoin will prove any different.” Seen in that light, discrepancies and gaps in the public record take on troubling overtones. In tracing a sample of Bitcoins from court records and forfeiture notices, Fortune turned up several instances of coins whose seizure was documented but whose sale was not. Court filings from 2014, for instance, show the IRS seized 222 Bitcoins from a marijuana dealer in Texas, but there is no documentation of its sale.Likewise, there is no auction record for 50.44 Bitcoins seized by the Secret Service in 2014 from a couple who ran an illegal drug and money-changing site under the name “JumboMonkeyBiscuit.” (Other cases reflect odd valuations—for instance, the forfeiture notice for the 99 Bitcoins seized in Salt Lake—worth around $800,000 in early February—lists the value of the currency as $0). Some of these coins could still be tied up in active cases or in the hands of the agencies that seized them. But since the Marshals Service doesn’t comment on its internal processes, there’s no way to know whether there’s a valid reason why they’re in limbo. There is no evidence to date of government agents misusing the forfeiture process to steal Bitcoin, and former prosecutors, including Histed, stress that corruption is the exception, not the rule. Nonetheless, the long gaps between seizure and sale only amplify the suspicions of defense lawyers and civil libertarians. And sources across the spectrum agree that the combination of opaque oversight and easy-to-move digital currencies creates a powerful temptation to go astray. Indeed, the first major federal Bitcoin bust proved as much. Jarod Koopman is the director of Cyber Crime in the Criminal Investigation division of the IRS. The tax agency’s crime-fighting wing has about 2,000 agents—accountants with a badge and a gun—and counts a growing number of cryptocurrency experts in its ranks. “They’re the cream of the crop,” Koopman says. But one of the team’s best-known busts is also its most disturbing, because it involved an inside job. During the Silk Road investigation, two agents—Carl Force of the DEA and Shaun Bridges of the Secret Service—went on a crime spree that would make Al Capone blush. Before Dread Pirate Roberts was arrested, they stole Bitcoin from the kingpin and his website and tried to extort payment from him. The crooked pair even posed as hitmen, staging a fake execution of an informer as part of another scheme to defraud Ulbricht. The IRS sleuths eventually snared Force and Bridges; both pleaded guilty in 2015 to charges related to the case. The agents carried out their scam before Ulbricht’s assets were seized, so they didn’t technically game the forfeiture process. Still, the case points up the potential for murky doings when digital currency meets forfeiture law. The Marshals Service, which is in the best position to provide a detailed accounting of seized property, is operating under something of a cloud itself. In September, after a lengthy investigation by staffers at the Senate Judiciary Committee, chairman Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) blasted the service for using forfeiture funds to pay for perks and luxury items such as “high-end granite countertops and expensive custom artwork,” much of it installed, appropriately enough, at a new Asset Forfeiture Academy in Houston. It wasn’t exactly a superheist, but it does nothing to assuage forfeiture critics or Bitcoin adherents, many of whom embrace the currency precisely because they lack faith in the integrity of governments. Koopman estimates that his IRS squad has helped seize tens or hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of virtual currency. That’s just one agency: Given that nearly a dozen others have forfeiture power, Koopman’s guess offers a sense of how far the government’s reach could extend into the digital coin market. And that reach will only grow as cryptocurrency becomes more commonplace. Finding illicit currency won’t get any less challenging. For years, bad actors have been “moving to other currencies that didn’t leave the same digital bread crumbs,” says Jud Welle, a former cybercrime prosecutor who is now a consultant with Aon. Many have abandoned Bitcoin for coins like Monero and ZCash, which offer the same sort of secure payment options but are all but impossible to trace. And more online black markets now bake so-called tumblers, which scramble transaction records, right into their checkout services, says James Smith, the CEO of forensic firm Elliptic. It adds up to a potentially endless digital cat-and-mouse game. And if law-enforcement agents ever do go rogue, the currency they steal will be that much easier to hide. The digital money, meanwhile, keeps rolling in. Another recent forfeiture.gov list showed a DEA seizure of six Bitcoins in New Jersey, along with 27 Bitcoins (worth approximately $330,000) taken from one Anton Peck by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Colorado. And an early February sting against a global credit card fraud ring reportedly netted the U.S. 100,000 more Bitcoins. In theory, Uncle Sam will be putting all of it up for auction—someday. A version of this article appears in the March 2018 issue of Fortune with the headline “Uncle Sam’s Secret Bitcoin Landfall.” |