没戏了!两位亿万富翁联手扼杀施乐与富士的合并交易

|

卡尔·伊坎是一位典型的独行侠。这位企业收购界的黑暗王子并不会像其竞争对手激进投资者一样,集结一批外部律师、投行家和公关公司,然后再发起进攻,而是依靠一支不到12人的内部金融分析师和律师团队,这支智囊团位于曼哈顿通用汽车大厦47楼,与这位82岁的老板一道不辞辛劳地工作着。但这仅仅是他的支持团队。至于合作伙伴,呵呵,有这个必要吗? 伊坎的公司Icahn Enterprises在今年的《财富》美国500强榜单上名列第136位,在财力方面基本上无需任何支持。他以现金和证券的形式握持着300多亿美元的战争基金。在策略方面,他也无需同行的任何谏言。令伊坎引以为自豪的是,他向董事会发送的那些臭名昭著的攻击信件都由他亲自执笔,而且会在信中大肆地对那些鸵鸟般“不敢面对现实”的董事或那些为了“蝇头小利”而同意出售公司的董事进行冷嘲热讽。 |

Carl Icahn typically works alone. The dark prince of corporate raiders shuns the usual clutch of outside attorneys, investment bankers, and PR firms that rival activists assemble for their assaults. Instead, Icahn relies on an in-house team of fewer than a dozen financial analysts and lawyers, a brain trust that toils alongside their controversial, 82-year-old boss on the 47th floor of Manhattan’s General Motors Building. But that’s just his support staff. As for partners, well, what’s the point? Icahn, whose Icahn Enterprises ranks No. 136 on this year’s Fortune 500, hardly needs any financial backing. He commands a war chest in cash and securities of more than $30 billion. Neither does he crave any counsel from peers on strategy. Icahn prides himself on personally composing the notorious attack letters he sends to boards of directors, piling on outraged barbs to skewer “ostrich” directors “with their heads in the sand” or those who’ve agreed to sell their companies “for a bowl of porridge.” |

|

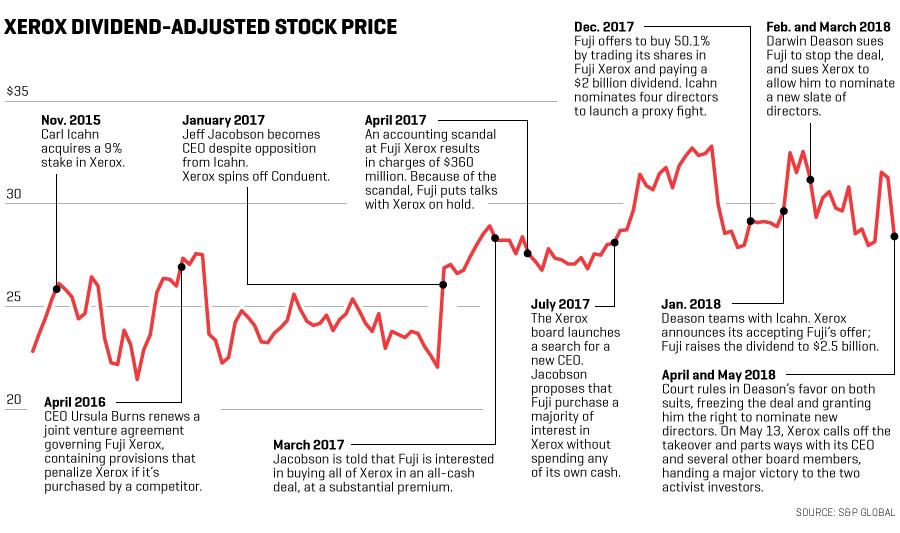

2015年底,当施乐成为伊坎的目标时,他无疑是打算再次启用孤军作战的战术。这家辉煌一时的企业对于伊坎来说是一个完美的候选目标。施乐由两个毫不相关的业务组成,而且它们的业绩均不尽如人意,一项业务是其传统的办公产品;另一项则是一个名为业务流程外包(BPO)的庞大部门,为公司和政府提供后台账单支付和数据处理服务。伊坎认为,他可以通过劝说施乐剥离其BPO业务来收拾这个残局。施乐目前是一个没人想买的烂摊子,但它可以分拆成两家专业公司,而这两个公司都可能会成为拥有高溢价的收购对象。如果拆分后仍没有买家立即抛出橄榄枝,伊坎认为他可以通过更换管理层来改善业绩,并通过抬升两家公司的股价来改善盈利。 伊坎向《财富》杂志透露:“施乐是我所见过的经营最差的公司之一。公司的两大业务均存在管理不善的问题。稍微有点头脑的人都会将其拆分,并聘请新管理层。施乐在利用自身强大的品牌方面毫无建树,有多少家公司的品牌还能够作为人们所熟知的动词(xerox的动词意思为“用静电复印法复印”——译注)来用?” 伊坎在2017年初实现了其目标,当时,施乐剥离了其BPO业务,后者成立了一家名为Conduent的新公司。事实证明,这笔交易的一半到目前为止已经大获成功:Conduent呈现出了一片欣欣向荣的景象,其稳健的股票业绩为伊坎带来了超过1亿美元的回报。 |

It was certainly Icahn’s intention to go it alone again when, in late 2015, he identified Xerox as a target. The once-great company was an ideal candidate for Icahn. It consisted of two divergent businesses, both of which were performing poorly—its traditional office products franchise, and a large division that provided back-office bill-paying and data processing services to companies and governments, a field called business process outsourcing (BPO). Icahn reckoned that he could clean up by prodding Xerox to spin off its BPO arm. Instead of a muddled mass no one wanted to buy, Xerox would split into two pure-play companies—either of which could be a takeover target at a fat premium. If buyers didn’t show up right away, Icahn figured he could improve performance by installing new management and profit by driving up each company’s stock price. “Xerox was one of the worst-run companies I ever saw,” Icahn tells Fortune. “Both sides of the business were being mismanaged. It was a no-brainer to split it up and bring in new management. Xerox was doing nothing with a great brand—how many companies have a name that doubles as a famous verb?” Icahn got his way when, at the beginning of 2017, Xerox spun off the BPO business as a new company called Conduent. And so far that half of the deal has proved a winner: Conduent has flourished, and its solid stock performance has generated a return of more than $100 million for Icahn. |

|

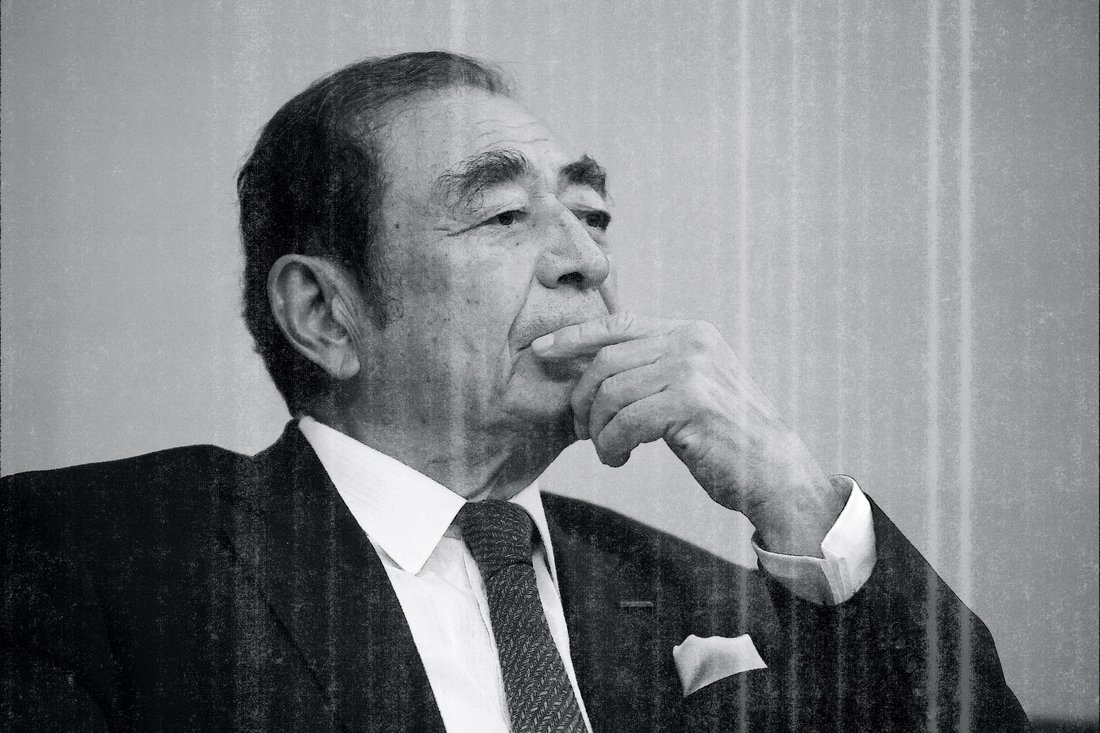

伊坎目前持有施乐9.2%的股份,是公司最大的单个股东。然而事实表明,伊坎靠施乐生财的征途已经成为了其50年职业生涯以来最为复杂的交易之一。事实上,这项交易是如此之艰难,伊坎打破了以往的惯例,与另一名合作伙伴开展合作。这名合作伙伴便是78岁高龄但依然充满活力的达尔文·迪森。达尔文于2010年以64亿美元出售了施乐的外包业务(构成了Conduent公司的主体),而且依然是施乐的第三大股东。除了在年龄和财富方面相仿之外,这对男士可谓是一个最古怪的组合。尽管毕业于普林斯顿大学,身高1.93的伊坎一直保留着其浓重的皇后区口音,而且作为经过华尔街历练的人士,他是一个典型的交易狂人。块头不大的迪森有着斗牛犬般的韧劲和长相,成长于阿肯色州农场的他是一个业务创建型人士。这对组合的年龄总和超过了160岁,共计持有施乐15.2%的股份,着实令人生畏。 伊坎和迪森共同发力,阻碍了一个在他们看来非常不划算的交易:日本富士计划以61亿美元收购施乐。5月13日,他们取得了这场斗争的重大胜利,当时,施乐董事会宣布将撤销此前同意的与富士公司的合并。在阻碍这一收购交易的过程中,他们的手腕似乎比对手更加高明,而这个对手便是富士首席执行官兼董事长古森重隆,后者就权力和能力而言与他们不相上下。在伊坎和迪森组队之前,78岁的古森似乎想把廉价收购这家美国知名企业作为其职业生涯的收官之作。古森在东京大学曾是美式橄榄球队的球员,称自己为“商业武士”,他是日本首相安倍晋三的密友之一,也是安倍最钟爱的高尔夫球友之一。 施乐董事会退出合并的决定只不过是近些年来华尔街众多最疯狂、最难以预料的对决所上演的最新剧情反转之一。富士称将对这一决定予以抗议。这场争斗的一些细节信息,也就是法庭记录和主要参与方的证词中广泛披露的信息,最为直接地暴露了施乐历史上所存在的企业治理失败问题。这一点的证实。在这场为期两年的闹剧中,董事会和前首席执行官产生了重大分歧,而就在这位首席执行官即将被炒鱿鱼的前几天,他送上了一份对日本巨头富士极为有利且难以抗拒的交易大礼,并似乎借此保住了自己的工作。然而最终,他只能眼睁睁看着这份协议在伊坎和迪森的施压之下化为泡影。 伊坎说:“施乐交易幕后所发生的事情异常疯狂,完全可以与电视剧《亿万》(Billions)的剧情媲美。在最终结果出来之前,我以为输定了。” 似乎具有讽刺意味的是,被时间遗忘的美国知名企业施乐在这场本世纪以来最具争议的收购战中成为了被争夺的主体对象。然而,在巨大的1800亿美元全球打印和文件市场中,施乐依然是一名重量级参与者。即便在剥离了Conduent之后,施乐庞大的规模足以让其跻身今年《财富》美国500强榜单第291位的位置,其销售额达到了103亿美元。同时,由于其品牌依然颇具号召力,而且公司也有能力进军快速发展的工业打印市场,施乐仍有可能东山再起。 根据被伊坎和迪森扼杀的这场交易,施乐将向现存的富士施乐公司(由施乐与富士组建的合资公司)出售其大部分权益。富士施乐专业从事在亚洲生产和销售施乐产品,并负责生产施乐在世界其他地区销售的大部分复印机。施乐股东将持有新富士施乐公司49.9%的权益,而富士将持有50.1%的控股权。富士无需利用任何自有现金来支付此次交易,只不过是贡献了它在现有合资企业富士施乐的大部分股权罢了。施乐股东将收到25亿美元一次性的股利,但并非由富士支付,而是由新富士施乐通过背负等额债务来支付。 伊坎和迪森的想法是正确的,这一复杂的交易将让富士完全控制施乐,而且只需支付的少量的溢价或零溢价。这对于富士股东来说是个好消息,但对于施乐股东来说却不尽然。大多数收购会带来至少20%-30%的“控股权溢价”。将控股权拱手让给富士意味着施乐股东将无法左右管理层的决策。在伊坎看来,这是一个无法令人接受的结果。伊坎说:“对于富士来说,它并不仅仅是私下交易那么简单,而是让施乐这家了不起的公司用100%的所有权来换取永久性的少数权益。无论富士在今后做出什么样的决策,持有49.9%权益的施乐也只能干瞪眼。” |

But Icahn’s crusade to cash in on Xerox, where he’s the largest individual shareholder with 9.2% of the stock, has proved to be one of the most complicated of his half-century career. It’s been so challenging, in fact, that Icahn has made an exception to his usual rule and teamed up with a partner: Darwin Deason, a feisty 78-year-old who sold the outsourcing business that now constitutes most of Conduent to Xerox in 2010 for $6.4 billion and remains Xerox’s third largest shareholder. Except in age and wealth, the two men are the oddest of pairings. The 6-foot-4 Icahn, who’s never lost his thick Queens accent despite a Princeton education, is a creature of Wall Street, and the quintessential deal junkie. The compact Deason—who in both tenacity and appearance resembles a bulldog—is a business builder who grew up on a farm in Arkansas. With a combined age of 160 and combined Xerox holdings of 15.2%, they make a formidable duo. Icahn and Deason joined forces to block what each regarded as a terrible deal: the planned $6.1 billion acquisition of Xerox by Japan’s Fujifilm. And on May 13, they won a significant victory in their battle when the Xerox board announced that it was pulling out of the agreed-upon merger with Fuji. In blocking the purchase, they appear to have outmaneuvered a foe whose power and savvy rivals theirs—Shigetaka Komori, Fujifilm’s CEO and chairman. Until Icahn and Deason teamed up, it appeared that Komori, 78, would cap his career by capturing an American icon on the cheap. Komori, who played American-style football at the University of Tokyo, is a self-described business “warrior” who’s one of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s closest friends and favorite golfing companions. The Xerox board’s decision to back out of the merger—a move that Fujifilm says it will contest—is just the latest twist in one of the wildest, most unpredictable Wall Street showdowns in years. And the anatomy of the conflict, extensively revealed in court records as well as testimony at trial by the main participants, exposes one of the most naked accounts of governance gone awry in corporate history. This two-year melodrama features a bitterly divided board and a former CEO who, days before he was scheduled to be fired, appeared to have saved his job by delivering a deal so favorable to Fuji that the Japanese giant could hardly say no—only to see the agreement fall apart under pressure from Icahn and Deason. “The stuff that went on behind the scenes at Xerox is so crazy you’d be amazed to see it on [the TV series] Billions,” says Icahn. “If it hadn’t actually happened, I wouldn’t have thought it was possible.” It might seem ironic that Xerox, an American icon that time forgot, stands at the center of one of the most contentious takeover battles of the current millennium. But Xerox remains a big player in a giant industry—the $180 billion worldwide printing and documents field. Even after spinning off Conduent, Xerox is still big enough to rank No. 291 on this year’s Fortune 500 list with $10.3 billion in sales. And its still-powerful brand and potential to expand into the fast-growing business of industrial printing give Xerox viable turnaround prospects. The deal for the company nixed by Icahn and Deason amounted to the sale of the majority ownership in Xerox to an existing joint venture with FujiFilm called Fuji Xerox—a business that exclusively makes and sells Xerox products in Asia, and manufactures most of the office copiers that Xerox sells in the rest of the world. Xerox shareholders would have held 49.9% of the new Fuji Xerox, and Fuji would have held the controlling 50.1% stake. Fuji would have put none of its own cash into the deal. Rather, it would have merely contributed its majority share in the existing joint venture. Xerox shareholders would have received a $2.5 billion one-time dividend—not paid by Fuji, but financed by adding the equivalent amount of debt to the new Fuji Xerox. Icahn and Deason charged, correctly, that this complex transaction would have enabled Fuji to take full control of Xerox while paying little or no premium. Great for Fuji—not so great for Xerox shareholders. Most takeovers include a “control premium” of at least 20% to 30%. And ceding control to Fuji meant that Xerox’s owners would have no sway over management decisions—an unacceptable outcome for Icahn. “It was not just a sweetheart deal for Fuji,” says Icahn. “You’d be trading full ownership of this great company to be in the minority forever. No matter what Fuji did with the business, your 49.9% is going to be completely powerless.” |

|

这两名义愤填膺的亿万富翁以自己的方式扼杀了这场交易。伊坎采用了他惯用的攻击方案——股权代理战。迪森则为伊坎提名的四名新董事提供了鼎力支持,同时也拿出了其所擅长的招数——打官司。他通过自己在King & Spalding律所的律师于2月和3月发起了两场声势浩大的诉讼。第一个诉讼称,由于施乐隐瞒了反兼并条款,因此公司有义务满足迪森延长董事提名截止日期的要求,这样,他便可以替换整个董事会。第二个诉讼则将施乐和富士都告上了法庭,指控施乐董事会和首席执行官因协商有利于其自身利益的交易,并让施乐股东继续执行不利交易,公然违反了其信托义务。该诉讼还指控富士密谋筹划交换条件,也就是施乐首席执行官为富士提供廉价收购施乐的机会,而富士则让其执掌新富士施乐。 伊坎并未参与迪森的诉讼。他向《财富》透露:“起诉董事会并不符合我的行事作风。一旦我们入主董事会之后,我们会努力与其他董事进行合作。”然而,正是因为其战友迪森在纽约法庭上的发力才让事情的内幕大白于天下。法庭记录披露了一批令人震惊的频繁往来邮件、文本、证词以及来自于施乐高管、董事和金融顾问以及富士高层经理的内部报告。 法院决定合并两项诉讼并同时裁决。在4月底于曼哈顿开展的为期两天的庭审当中,施乐时任首席执行官杰夫·雅各布森、董事长罗伯特·齐根(一位持不同意见的董事)和公司的投行高管均在发誓后提供了广泛的证词。本文记者参与了这一庭审,并查看了700多份由法官开封的证据。《财富》还广泛采访了伊坎和迪森的代理人。施乐和富士均以诉讼为由,拒绝对其高管或董事进行采访,但证词、口供和邮件却为我们提供了一扇窥探各方动机和想法的难得窗口。 在庭审结束之际,法官巴利·奥斯特雷格(此前亦是一名知名的并购诉讼律师,在私人执业领域有着40多年的经验)提供了一份言辞犀利的意见,最终让迪森在这两场诉讼中大获全胜。他还强烈抨击了雅各布森、齐根和施乐董事在这一过程中所扮演的角色,称雅各布森与富士进行协商存在重大的利益冲突,因为这一私下交易的条件便是保留其职务。最终,奥斯特雷格写道,雅各布森违背了其信托义务,齐根亦是如此。 在法律文件中,施乐和富士给出了一个理直气壮的理由,这一点在雅各布森和齐根的证词中也有所体现。他们的律师认为,在雅各布森、齐根和董事会所开展的这项交易中,富士是唯一一个合理的买家,而且其他买家对此次交易均不感兴趣。富士认为,公司并未向雅各布森许诺首席执行官一职(这一观点遭到了董事的反驳),而且他只是这一职务的首要人选,因为“这位才华横溢的高管完全有条件实现新公司的协同效应,从而造福富士和施乐的股东”。施乐的律师认为,齐根完全有权力派遣首席执行官去进行交易谈判,而且齐根在证词中提到,他曾建议董事会撤销其解聘雅各布森的决定,因为雅各布森的业绩在2017年底突然出现了改观。雅各布森在自己的证词中指出,这种让他将自身或富士的利益置于公司股东利益之前的建议,是违背良心的,也是不合情理的。 这一有利于迪森的一边倒式判决引发了一场持续了两周的清算闹剧:施乐一开始宣布与伊坎和迪森达成和解,然后又撤销了这一决定,转而与富士进行协商,结果不欢而散。随后在5月13日,施乐董事会再次改变了其之前做出的决定,并与伊坎和迪森达成协议,并宣布终止并购,同时炒了雅各布森的鱿鱼。齐根与其他四名董事也离开了董事会,取而代之的是由伊坎和迪森挑选的高管。新任首席执行官是数据处理领域的专家约翰·维森丁,因帮助企业东山再起而闻名。 如今,施乐称公司将公布所有意向收购方的要约信息。与此同时,富士仍在力争重启最初达成的收购交易,并在施乐退出后发布了一份带有挑衅意味的声明:“我们认为,施乐无权终止这一协议,而且我们正在审视可用的一切方法,包括通过诉讼来索赔损失。”这两家公司为何走到了今天这个地步?我们不妨先了解一下它们之间的历史渊源。 2015年底伊坎将施乐当成目标时,施乐业绩已连续数十年衰退。1906年施乐在纽约州罗切斯特创立,刚开始做照相纸,上世纪40年代末推出了全世界首个高速复印机,随着其硬件成为大公司、律师事务所和政府机关文件室里的主力机器,公司业绩也节节上升。但上世纪80年代开始,个人电脑逐渐普及,纸质文件打印和复印需求大为减少。关键专利到期后,施乐面临着日本竞争对手理光和佳能的激烈竞争,还有美国的惠普。 为了应对不断衰退的核心业务,施乐(现在总部位于康涅狄格州诺瓦克)向其他领域拓展,包括金融服务,最近的动作是2010年收购迪森创立的外包服务公司Affiliated Computer Services。但新业务跟原本制造出售打印机复印机的业务相差太远,后来施乐退出了大部分,期间进行了一轮又一轮重组。值得注意的是,施乐旗下的打印专营服务,即向大公司提供全套硬件、耗材和维修服务,虽然不断缩减,但利润丰厚,再加上不断削减成本,所以其现金流水平一直保持健康。因此现在的施乐不过是座逐渐融化的冰山,谈不上灾难。 施乐与富士从1962年就开始合作,当时施乐跟富士合作在富士大本营日本制造并销售施乐的办公设备。之后39年里,施乐跟富士平等合作,两家各持有50%股份。2000年情况发生变化。施乐销售部门重组失败,收入受到重创,深陷债务之中。由于施乐濒临破产,首席执行官保罗·阿莱尔急忙出售资产筹集资金。施乐首先将独家拥有的中国经营权出售给富士施乐,作价5.5亿美元。2001年初,施乐出售富士施乐的25%股份换得13亿美元,由此富士持有合资公司75%股份,掌握控股权。现在合资公司在亚洲和环太平洋市场350亿美元规模的市场里出售产品,施乐却仅握有四分之一股权。施乐实力逐渐减弱,富士却不断变强。在古森领导下,富士没有像柯达一样没落,而是成功由胶片制造商转向不断增长的领域,例如医疗设备和化妆品。股权转让后,虽然富士施乐主要依靠施乐的专利和工程技术,富士却能随着亚洲不断发展享受更多收益。 不过施乐蒙受的打击还不只是销售和利润比例下降。2001年的交易包括一项新协议 ,叫合资企业协议或简称JEC,规定了合作双方的治理权,还对出售施乐规定了严重的处罚条款。合资企业协议和另一项协议——技术协议或简称TA将施乐牢牢掌控住。每一次签订技术协议生效五年,目前这份由前首席执行官乌苏拉·伯恩斯于2016年签订,2021年3月失效。根据两份协议规定,如果施乐业务遭出售,将失去治理权,技术协议失效前无法在亚洲地区重新使用品牌名称,且技术协议失效后还要两年才可回收品牌。 |

The two angry billionaires fought the deal in their own ways. Icahn deployed his preferred plan of attack, the proxy battle. Deason pledged to back Icahn’s slate of four new directors, but also went his own way by fighting in the courts. He brought two sweeping lawsuits through his attorneys at King & Spalding, unveiled in February and March. The first claimed that because Xerox had concealed a poison pill provision, the company was obligated to grant Deason’s demand to extend the nominating deadline so that he could replace the entire board. The second, brought against both Xerox and Fuji, charged that Xerox’s board and CEO blatantly violated their fiduciary duties by negotiating a deal that promoted their own interests, while sticking Xerox shareholders with a bad deal, and accused Fuji of conspiring in a quid pro quo—the CEO delivers a bargain price, and Fuji puts him in charge of the new Fuji Xerox. Icahn didn’t join Deason’s suits. “I find suing boards distasteful,” he tells Fortune. “Once we’re inside the boardroom, we try to work collaboratively with other directors.” But it was his partner’s assault in the New York courts that laid bare the inside story. The court records exposed a trove of frequently shocking emails, texts, depositions, and internal reports from executives, directors, and financial advisers at Xerox, and top managers at Fuji. At a trial in Manhattan over two days in late April—the two lawsuits were consolidated and decided together—Xerox’s then-CEO Jeff Jacobson, its chairman Robert Keegan, a dissident director, and its investment banker all gave extensive testimony under oath. This reporter attended the trial and reviewed the more than 700 exhibits, all unsealed by the judge. Fortune also talked extensively with Icahn and representatives for Deason. Xerox and Fuji both declined to make any of their executives or directors available for interviews, citing the litigation. But the testimony, depositions, and emails provide a rare window into the motives and thinking of all the players. At the conclusion of the trial, Judge Barry Ostrager—himself an esteemed former M&A litigator with more than 40 years in private practice—issued a scalding opinion that granted Deason big wins on both of his suits. He also delivered a stinging condemnation of the role of Jacobson, Keegan, and Xerox’s directors, stating that Jacobson was “massively conflicted” in his negotiations with Fuji because delivering a sweetheart deal promised to save his job. As a result, Ostrager wrote, Jacobson was “in breach of his fiduciary duties,” as was Keegan. In their legal filings, Xerox and Fuji present a righteous scenario that echoed in the testimony from Jacobson and Keegan. Their attorneys argue that Jacobson, Keegan, and the board pursued a deal with the only logical buyer, when no other acquirers were interested. Fuji argues that Jacobson wasn’t promised the CEO job—a view contradicted by directors—but was simply its top choice as “a talented executive well-suited to achieving the synergies that will benefit shareholders of Fuji and Xerox alike.” Keegan was fully justified in assigning the CEO to negotiate a deal without the full board’s approval, argued Xerox’s attorneys, and Keegan testified that he encouraged the board to reverse its decision to fire Jacobson because his performance suddenly improved in late 2017. In his testimony, Jacobson called the suggestion that he put his or Fujifilm’s interests before those of his shareholders “reprehensible and unconscionable.” The overwhelmingly pro-Deason decisions kicked off a tumultuous two-week period of reckoning: Xerox first announced a settlement with Icahn and Deason, then withdrew from it and engaged in talks with Fujifilm that turned acrimonious. Then, on May 13, Xerox’s board reversed itself again—coming to terms with Icahn and Deason and announcing that the merger was terminated and Jacobson was out as CEO. Keegan and four other directors also departed, to be replaced with execs chosen by Icahn and Deason. The new CEO is John Visentin, a well-regarded turnaround expert in data processing. Xerox now says it will field offers from all interested bidders. Meanwhile, Fuji is still battling to revive the original deal and released a defiant statement after Xerox pulled out: “We do not believe that Xerox has the legal right to terminate our agreement, and we are reviewing all of our available options, including bringing a legal action to seek damages.” To understand how the two companies reached such an impasse, it helps to review the history between them. By the time Icahn zeroed in on Xerox in late 2015, the company had been shrinking for decades. Started as a photographic-paper maker in Rochester, N.Y., in 1906, the company introduced the world’s first high-speed copiers in the late 1940s, and thrived as its hardware formed the essential engine room for document production inside big companies, law firms, and government agencies. But starting in the 1980s, mass adoption of the personal computer sharply curtailed the need for paper printing and copying. As its key patents expired, Xerox faced stiff competition from Japanese rivals Ricoh and Canon, as well as Hewlett-¬Packard in the U.S. To counteract flagging sales in its core franchise, Xerox (now based in Norwalk, Conn.) diversified into such fields as financial services, and most recently, the 2010 purchase of Affiliated Computer Services, the outsourcing outfit founded by Deason. Those businesses fit poorly with making and selling printers and copiers, and Xerox exited most of them—while at the same time engaging in round after round of restructuring. Remarkably, Xerox’s highly lucrative, if shrinking, managed print services franchise—in which it furnishes a full package of hardware, supplies, and maintenance to big companies—combined with constant cost-cutting have kept free cash flow at healthy levels. Hence, Xerox is today a gradually melting iceberg, but far from a catastrophe. Xerox’s partnership with Fujifilm dates to 1962, when Xerox and Fuji formed an alliance to manufacture and sell Xerox office products in Fuji’s home market of Japan. For 39 years, Xerox and Fuji were equal partners, each holding 50% of the shares. Then came a pivotal moment in the year 2000. A botched restructuring of its sales force hammered Xerox’s revenues, and it was drowning in debt. As Xerox stood on the brink of bankruptcy, CEO Paul Allaire rushed to raise cash by selling assets. First, Xerox sold its China franchise, which it owned independently, to Fuji Xerox for $550 million. Then in early 2001, it pocketed $1.3 billion in exchange for 25% of Fuji Xerox—giving Fuji a 75%, controlling stake in the joint venture. As a result, Xerox now owns just one-fourth of the vehicle with exclusive rights to make and sell its products in the $35 billion Asia and the Pacific Rim markets. And as Xerox weakened, Fuji got stronger. Under Komori, it avoided Kodak’s fate by successfully diversifying from photographic film into such growth fields as medical equipment and cosmetics. The sales assured that Fuji would benefit disproportionately from growth in Asia, even though Fuji Xerox relied heavily on Xerox’s patents and engineering. The damage to Xerox, however, extended far beyond its diminished share of sales and profits. The 2001 transaction included a new agreement called the Joint Enterprise Contract or JEC, that outlined the governance rights of the two partners, and established severe penalties that would be triggered by a sale of Xerox. It’s the combination of the JEC, and a second pact—the Technology Agreement or TA—that puts Xerox in a real bind. Each TA runs for five years; the current one, approved by former CEO Ursula Burns in 2016, expires in March 2021. Under the two agreements, if Xerox is sold, it not only loses its governance rights, it can’t regain its brand name in Asia until the TA expires, and doesn’t get it back exclusively for another two years. |

|

这对潜在买家来说意味着什么?如果无法撤销合资企业协议和技术协议,收购施乐的竞争对手或私募股权公司对富士施乐经营毫无话语权,且2023年以前都不可在亚洲完全独立制造和销售施乐的产品。 两份协议组成了一份对施乐影响严重的所谓毒丸计划,想出售给富士之外的第三方极其困难。神奇的是,相关条款从未公布于世,直到1月31日施乐和富士宣布合并人们才知道。伊坎和迪森听说之后勃然大怒。 伊坎刚开始买入施乐股票时就想更换管理层。“我希望Conduent和施乐都能有全新称职的管理层,”伊坎表示。“我直接告诉伯恩斯,两家公司她一家也管不好。”(伯恩斯拒绝为本文发表评论。)2016年中,伊坎与施乐董事会达成协议,以顺利从外部提名首席执行官。他签署了一份“冻结”协议,承诺代理战期间不会影响施乐董事会,还签署了保密文件,承诺保密前提下获知内部信息。为了争取这些让步,施乐同意任命伊坎的副手约翰逊·克里斯托多洛担任董事会观察员,2016年中开始担任正式成员。但6月伯恩斯宣布二号人物杰夫·雅各布森接替自己担任首席执行官。伊坎非常不希望出现这种局面。“雅各布森是伯恩斯的助手,”伊坎说。“他是严重拖累施乐发展的管理层一员。” 不过起初看起来,雅各布森2017年1月1日接手伯恩斯之后有可能按照伊坎希望的方向推动交易。以下情况在法庭记录里有详细记录。3月初雅各布森第一次前往东京的富士总部时,古森和总裁助野健儿表示有意以全现金方式收购施乐100%股份,且表示接受超过施乐30美元现价30%的溢价。3月16日,雅各布森与董事会商量后写信给富士,表示施乐愿意接受支付“合理溢价”的全现金交易,而且施乐在单独制定很有前景的计划,可以“推动增速超过同行”,所以并不着急交易。 为什么富士获得富士施乐绝大部分收益,之前也从未承诺全盘收购施乐,突然要提出100%收购?原因可能是富士担心富士拆分后只剩下纸面管理,可能有其他收购者趁虚而入。合资公司可以提供保护,但仍可能被绕过。 关于交易的讨论很快受到争议干扰。2017年4月20日,富士公开披露富士施乐内部一起重大的财务丑闻,而且宣称该事件会导致富士和施乐蒙受巨大损失(不过当时没有宣布具体金额)。富士掌控着富士施乐管理层,83年历史上第一次延迟发布季报。由于该次丑闻,富士通知施乐,要专心处理富士施乐内部问题,所以收购一事无法继续。 施乐董事会也面临危机,即领导层出现问题。董事们对新任首席执行官失去信心。丑闻爆发当天的董事电话会上,有几位董事指责雅各布森之前的表现。很快接替伯恩斯担任总裁的齐根在提交法庭的书面说明中表示,董事们指责雅各布森“学习速度太慢”、“喜欢抱怨”、“过于自负”,而且“不愿意倾听”。齐根还记下当时一个预言般的问题,“我们真需要他来完成‘果汁’计划么?”“果汁”是富士施乐股权交易的代号。 |

What would this mean for a potential buyer? If the JEC and TA went unchallenged, a rival or private equity firm that buys Xerox would have no say in running Fuji Xerox and would be unable to independently and exclusively make and sell Xerox products in Asia until early 2023. Together, the two agreements add up to a crippling so-called poison pill for Xerox—making a sale to a partner other than Fuji extremely difficult. Incredibly, the existence of the provisions was never disclosed publicly until Xerox and Fujifilm announced that they were merging on Jan. 31. By that time, Icahn and Deason were already fuming. Icahn had been trying to install new leadership since he first got into Xerox’s stock. “I wanted new, competent management at both Conduent and Xerox,” says Icahn. “I told Burns I didn’t believe she should run either one.” (Burns declined to comment for this story.) In mid-2016, Icahn reached an agreement with the Xerox board that he reckoned would smooth the way to naming an outside CEO. He signed both a “standstill” pact, under which he pledged not to challenge the Xerox board in a proxy fight, and a nondisclosure document that entitled him to inside information that he was obligated to keep secret. In exchange for those concessions, Xerox agreed to name an Icahn lieutenant, Jonathan Christodoro, first as an observer to the board, then as a full member starting in mid-2016. But in June, Burns announced that her No. 2, Jeff Jacobson, would succeed her as CEO. He was exactly what Icahn didn’t want. “Jacobson was an acolyte of Burns,” says Icahn. “He was part of the team that badly hurt Xerox.” At first, however, it appeared that Jacobson, who took over for Burns on Jan. 1, 2017, might deliver the kind of deal that Icahn wanted. The following account is extensively documented in the court records. During Jacobson’s first visit to Fuji’s Tokyo headquarters in early March, Komori and president Kenji Sukeno expressed interest in purchasing 100% of Xerox in an all-cash transaction, and noted that they understood that a typical premium would amount to 30% over Xerox’s current price of $30. On March 16, Jacobson, after consulting with the board, wrote a letter to Fuji confirming that Xerox wanted only an all-cash transaction at an “appropriate premium,” and had no need to do a deal since it was pursuing a highly promising standalone plan that would “drive growth well above our peers.” Why did Fuji suddenly suggest a 100% deal when it already got most of the benefits from Fuji Xerox, and had never before proposed buying all of Xerox? The answer is probably that Fuji was concerned that, with Xerox now a pure-play in document management post-split, other suitors might pounce. The joint venture agreements provided protection, but it was also possible that they could be circumvented. But the deal talks were soon derailed by controversy. On April 20, 2017, Fujifilm publicly disclosed a gigantic accounting scandal at Fuji Xerox that, it revealed, would saddle Fuji and Xerox with big losses (although it didn’t disclose an amount at the time). Fuji, who controlled management of Fuji Xerox, delayed filing its quarterly statements for the first time in its 83-year history. Because of the scandal, Fuji informed Xerox that it needed to concentrate on fixing Fuji Xerox and couldn’t proceed with an acquisition. Meanwhile, Xerox’s board was facing another crisis—of leadership. The directors were already losing confidence in the company’s new CEO. At a board meeting the day the scandal broke, held on the phone, a number of directors skewered Jacobson’s early performance. In his handwritten notes from the meeting that were later submitted to the court, Keegan, soon to replace Burns as chairman, recorded complaints that Jacobson was “too slow on the learning curve,” “a whiner,” “overconfident,” and exhibited “poor listening skills.” Keegan also jotted down a prophetic question, “Do we need him to complete ‘Juice’?” referring to the code name for a Fuji-Xerox transaction. |

|

此时迪森正在加勒比海上,乘着203英尺长意大利造的游艇观察局势,他有点担心了。迪森并不清楚毒丸条款,但已经开始怀疑富士使用什么手段控制施乐。迪森的胆识不输伊坎。高中毕业第二天,迪森就留离开长大的农场,去塔尔萨的海湾石油公司邮件收发处谋得一份工作。他经常跟做数据处理的人们交流。后来他搬到德州,开始帮银行处理ATM交易。1988年他创立Affiliated Computer Services,其中一个大客户是快易通电子收费系统E-ZPass。他介绍自己做事方式时说,“如果跑步机的时速是每小时100英里,而你只能跑80,就会被甩出去。关键是自我约束。” 5月底,迪森私下写信给施乐提醒道,根据协议中隐含的条款,“公司控制权如果发生变更,施乐可能遭受巨大损失。”施乐回应迪森称,迪森签署保密协议后才愿意公布协议。迪森表示拒绝,之后没怎么联系过施乐,直到1月《华尔街日报》报道称富士的交易可能失败。 雅各布森在法庭上表示,直到5月中旬他都不知道董事会对他不满。但他很快就知道自己跟伊坎的立场。因为伊坎邀请雅各布森去曼哈顿现代艺术博物馆旁边的顶层豪宅吃饭,两人坦诚聊了聊。根据《财富》对伊坎和雅各布森的采访以及法庭证词,伊坎告诉雅各布森他希望出售施乐,如果雅各布森不愿意,伊坎就会想办法换掉他。雅各布森对受到威胁很不满。“我告诉他,就算你赶走我,顶多就是我回家陪伴美丽的老婆和家人,”雅各布森的证词称。(雅各布森拒绝为本文接受采访。)伊坎对雅各布森的增长“长期计划”表示非常失望,该方案打算未来五年每股盈余仅提升8%。“我告诉他,‘我们很懂财务数字,’”伊坎说,“这种计划对股东来说毫无价值。” 伊坎告诉齐根,他很不看好雅各布森,还有下一步策略。据齐根证词,他很快就认为董事会面前只有一条路。施乐“得尽快卖掉”。 雅各布森接手工作,努力跟富士重启谈判。为了给对方施加压力,他还提到来自伊坎的威胁,尤其是伊坎可能以财务丑闻为借口撤出合资公司。6月底,雅各布森给齐根发邮件称,“我用伊坎说事确实是因为需要点紧迫感,他们(富士)也能理解。” 同样在6月,富士对富士施乐的财务丑闻发布了独立的调查报告,称损失共3.6亿美元,其中施乐一方承受9000万美元。报告中还指责富士施乐的“隐瞒文化”,抨击富士疏于监管。6月12日的业绩通报会上,古森为财务丑闻一事鞠躬致歉。 7月有两个关键时刻。首先是7月10日雅各布森和富士两位高管在施乐一方银行Centerview Partners曼哈顿办事处会面。富士阵营抛出了重磅炸弹,称不可能收购施乐100%股份,因为施乐太贵。该说法有点令人费解,因为当时施乐股价比富士3月表示要100%收购时还低3%。但施乐并没有坚持长期以来的立场,即100%股份以及全现金交易,而是主动提出令人惊讶的建议:Centerview建议富士收购刚好超过50%施乐股份,而且不需要现金。 以前Centerview也用同样的策略促成H.J.亨氏-卡夫合并,当时亨氏股东掌握新公司卡夫亨氏51%股份。目前并不清楚是Centerview还是雅各布森提出该方案;雅各布森宣称是Centerview提出该想法。但雅各布森接受了。同一天,他给齐根和董事安·里斯发信息称“这次算是孤注一掷。门已经打开,我们可能还有一线机会。”但他也彻底放弃了全现金买断股份的方案。 由于伊坎签署了保密协议,也能收到克里斯托多洛的报告,所以很快知晓了49.9%少数股权的方案,他很生气。伊坎的想法是,要么富士支付“真金白银”,要么用伊坎的话说,“我们要逐渐从富士施乐撤出业务,最后结束合资公司,在亚洲夺回施乐品牌,”显然富士不希望这样。 虽然伊坎一再要求,但直到10月中旬谈判才重新开始。在雅各布森推动下,富士终于聘请摩根士丹利当财务顾问。虽然谈判期间施乐唯一出现的是雅各布森,但10月底董事会做出关键决定:由约翰·维森丁接替雅各布森的职位,维森丁曾在IBM工作多年,之前成功带领文档外包商Novitex走出困境,也是伊坎强烈支持的人选。12月11日维森丁正式开始工作,也是伊坎提出争夺代理权的截止日期。 董事会还一致决定雅各布森应该停止与富士谈判。两位董事证词显示,董事会决定应由维森丁负责谈判。11月10日,刚从脚部手术恢复的齐根在韦斯切斯特县机场与维森丁负责会面,还提醒说董事会打算找人替他的位子。双方均表示,齐根告诉雅各布森尚未最终决定。 然而克里斯托多洛和董事谢丽尔·克朗加德坚称董事会已明确表示要换人。 但雅各布森手里还有一张王牌。按照计划,11月14日富士高层要在纽约讨论交易事宜,而雅各布森预计在11月21日与古森会面。雅各布森告诉富士计划主管河村隆(音译)会面要取消,河村的回复是如果无法如期会面,首席执行官古森会“非常失望”,双方“交易可能无法顺利进行”。雅各布森如此转告了齐根。 事情发生出人意料的转折:齐根推翻了董事会的一致决定,允许雅各布森继续与富士谈判。“我做了个战场决策,” 齐根在证词中称。齐根的备忘显示,他坚信不管雅各布森有多少弱点,但对促成合并至关重要。齐根只告诉了Centerview的银行家和一位董事安·里斯,允许即将被解雇的雅各布森继续负责这笔交易。 雅各布森一方面得到总裁支持,另一方面也得到富士的支持和鼓励。 川村发给首席执行官雅各布森的信息显得关系相当亲密,吹嘘双方结成联盟对抗伊坎。“我们应该组成团队,对抗共同的敌人。”11月12日川村发给雅各布森的信息称。“朋友,我们在同一阵线。”雅各布森回复道。雅各布森会见古森的前一天,川村向雅各布森发送的信息里强烈暗示,古森希望帮雅各布森保住工作。他表示古森“会认真倾听你的现状,看看我们能做什么。”随后雅各布森发信息给Centerview的赫斯,“河村说如果没我在,交易就做不成。”11月21日与古森会面时,雅各布森提议富士公司提供20亿美元的一次性股息,加在交易条款中,但数量并不算大。 留下雅各布森后,齐根严重激怒了最大的个人股东。伊坎不断找齐根,让他任命维森丁为首席执行官,而且伊坎表示,齐根总说很快就调整。“齐根只是口头说啊说,”伊坎表示。“他一直说维森丁很快就能接任,但并没有动作。与此同时,雅各布森却在幕后搞小动作。真希望他经营公司的本事能有背后捣鬼一半强。否则他早就帮我赚很多钱了。” 11月30日,富士向施乐提出正式要约,按照之前7月的约定,施乐持有富士施乐49.9%股份,此外提供雅各布森提议的20亿美元股息。12月4日,齐根在董事会宣布了交易条款,此时除了齐根和里斯,其他董事基本上都不知道雅各布森在跟富士接触。其中几位表示非常震惊,三周前董事会就一致同意禁止雅各布森与富士商谈,他居然还能参与谈判交易。 由于已签署保密协议,伊坎可以了解董事会审议情况,很快便知道雅各布森与富士谈判的拟议条款。“当时我火冒三丈,”伊坎说。“齐根一直说,‘相信我。’结果我看到交易条款,对他说,‘你就弄出这些来?疯了么?’他就是骗我!我们都知道雅各布森连施乐都管不好,怎么可能管好两倍规模的公司?” 克里斯托多洛表示抗议,12月8日从董事会辞职。他离开后伊坎也不必再遵守冻结协议,伊坎有权任命四位董事,12月11日周一伊坎就行使了权利。法律文件显示,雅各布森、齐根和富士高管都希望相关条款令伊坎满意,但都清楚知道伊坎可能发起代理权战争。 Centerview向董事会介绍时宣称,与富士交易是施乐摆脱伊坎的绝好机会。因为提出交易的董事会几乎从未在股东投票中输过。根据计划,选举董事和对交易投票将在年度股东大会上连续进行。Centerview表示,股东只有反对交易时才会支持伊坎一方,但可能性很小。所以伊坎很有可能在投票之前卖出股份,要么就等着在年度股东大会上输掉。 1月,随着交易日期临近,雅各布森在新富士施乐公司的首席执行官一职也似乎日渐稳固。1月16日,川村发信息给雅各布森称,“我明确请古森告诉齐根,他希望杰夫担任首席执行官。”事实上,古森并未提出该要求。古森只提到联系首席执行官,其中要有一名由富士指定。齐根反对后,古森便放弃了。雅各布森坚称自己当首席执行官不是达成协议的条件。但根据董事会成员克朗加德的证词,Centerview和外部顾问公司Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison都告诉董事会,一定要让雅各布森当首席执行官。4月27日,Centerview的大卫·赫斯在证人席上被问到“Centerview有没有建议董事会由雅各布森担任首席执行官,才能继续推进交易,”他简单回答道,“是的。” 1月31日,施乐和富士宣布合并。经过齐根在最后一刻的游说,古森同意稍微增加股息,加到25亿美元。一开始施乐股价略有上升,但投资者研究交易细节后股价急转直下。作为信息披露一部分,施乐首次公布了完整的合资公司协议,也包括毒丸计划。迪森大怒,立刻开始准备诉讼。 另一项披露的信息也影响了最终合并。为了赶着完成交易,施乐和富士决定不等富士施乐提交审计后的财务报表,最终报表会统计出财务丑闻导致的准确亏损数据。施乐表示,交易条款规定如果亏损远超未经审计报表中的统计,施乐有权取消合并。4月24日,富士施乐终于宣布审计后的数据,亏损由之前预计的3.6美元左右确定为4.7亿美元,增加了31%。施乐承担的损失由之前的9000万美元增加到1.18亿美元。最终施乐也确实以财务纠纷为由取消交易。 合并最终取消之前,还发生了些小插曲。5月13日施乐发给富士的终止协议里披露了一个情况。施乐称由于发生财务丑闻,其有权取消交易,因为富士施乐没有按时提交经审计数据,也因为最终数据与最初估计差得太多。 但文件也第一次显示,雅各布森做了很多努力争取更好的条件并挽救交易,虽然施乐公开宣称达成的协议对股东很有利。3月和4月,雅各布森两次前往东京跟古森谈判时,都在争取更好的价格。审判开始两天前的4月24日,齐根通过视频电话会向古森提出请求。奥斯特雷格法官宣布有利迪森的判决第二天,齐根在写给古森的信中进一步恳求。5月9日和10日,施乐的银行家和律师们与富士一方的代理达成协议。施乐要求:富士增加12.5亿美元股息,不能通过富士施乐举更多债,要从富士自己的现金流中提供。如果实现,股东每股可多获得5美元股息,增幅约17%。 古森并没有买账。他告诉齐根5月21日那周之前没法谈任何新条款。双方分歧越来越大,5月10日富士发布新闻稿称,虽然施乐一直在争取更多股息才愿意继续交易,但并未收到施乐新提议。施乐在终止通知中称,“富士的声明显然是错的。根本站不住脚,由此可见富士缺乏诚意。” 富士发怒的同时,伊坎和迪森却在法庭上和董事会里庆祝胜利。维森丁终于就任首席执行官,他们希望施乐的业绩会止跌回升。合并告吹后,他们希望能真正开始剥离业务。如果富士想通过毒丸计划阻止交易,伊坎和迪森也可能以财务丑闻为理由在法庭上提出质疑。 与此同时,两位合作伙伴还有个私人赌局要结算。《财富》得知伊坎和迪森赌了5万美元现金,赌注是迪森会输掉诉讼,没法推迟提名董事的期限,德州佬迪森愉快地下了注。“我赌博一般很少输。估计因为这点人们都说千万别跟卡尔·伊坎对赌,”伊坎笑着说。“但这次如果我输了,反而很高兴。”现在他跟迪森的赌注是,全力合作能否通过施乐大赚一笔。(财富中文网) 本文原刊于2018年6月1日出版的《财富》杂志。 译者:冯丰 审稿:夏林 |

Monitoring the situation from his sumptuous 203-foot, Italian-built yacht in the Caribbean, Deason was getting worried. He didn’t know about the poison pill provisions, but he was suspicious that Fuji had some kind of a string on Xerox. Deason is every bit Icahn’s match in grit. The day after his high school graduation, he left the farm where he was raised for a job in the mailroom at Gulf Oil in Tulsa. There he hung out with the data processing folks. Moving to Texas, he pioneered the processing of ATM transactions for banks. In 1988 he founded Affiliated Computer Services—a major customer was E-ZPass. He describes the way he ran things thusly: “You’re on a treadmill going 100 mph, so if you’re just going 80, you get thrown off. It’s self-policing.” In late May, Deason wrote a private letter to Xerox expressing alarm that conditions hidden in the agreements threaten “a potentially major loss in value for Xerox in any change in control of the company.” In response to Deason’s request, Xerox stated that it would only release the agreements if Deason would sign his own NDA. Deason refused, and had little contact with Xerox until January when reports of a possible Fuji deal broke in the Wall Street Journal. Jacobson claimed in his testimony at trial that, until mid-May, he had no idea the board was dissatisfied with his performance. But he soon learned where he stood with Icahn. The activist invited Jacobson to his penthouse apartment adjacent to Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art for dinner and some frank talk. According to both Fortune’s interviews with Icahn and Jacobson’s notes and testimony, Icahn told Jacobson that he wanted Xerox sold—and if Jacobson couldn’t sell it, Icahn would push to have him replaced. Jacobson took umbrage with the threat. “I told him the worst thing you can do to me is that I go back to my beautiful wife and beautiful family,” Jacobson testified. (Jacobson declined to be interviewed for this story.) Icahn also expressed extreme disappointment in Jacobson’s “Long Range Plan” for growth, which was targeted at raising EPS by a mere 8% over five years. “I told him, ‘We understand numbers,’ ” says Icahn. “This plan produces no value for shareholders.” Icahn shared his dim view of Jacobson and his strategy with Keegan. And soon after Keegan decided, according to his testimony, that only one path remained for the board. Xerox “needed to sell post haste.” Jacobson grabbed the baton, and pushed hard with Fuji to restart talks. To ratchet up the pressure, he invoked the looming threat of Icahn—especially the idea that Icahn might try to end the joint venture, using the accounting scandal as an out. In late June, Jacobson emailed Keegan, “I did play the Icahn card as a reason we need a sense of urgency and they [Fuji] appreciate this.” Also in June, Fuji released an independent report on the Fuji Xerox accounting scandal that put the total losses at $360 million, including a $90 million hit to Xerox. The report also assailed a “culture of concealment” at Fuji Xerox, and slammed Fuji for lax oversight. At an earnings briefing on June 12, Komori bowed and apologized for the scandal. Two watershed moments came in July. The first was a meeting on July 10 at the Manhattan offices of Centerview Partners, Xerox’s bankers, between Jacobson and two leading executives from Fuji. The Fuji camp dropped what should have been a bombshell, stating that a deal for 100% of Xerox was now impossible because Xerox was too expensive—a puzzling assertion, since its stock price was 3% lower than when Fuji expressed interest in a 100% acquisition in March. But instead of maintaining its long-held position that only a 100%, all-cash transaction would work, the Xerox camp voluntarily advanced an extraordinary proposal: Centerview suggested that Fuji purchase just over 50% of Xerox in a deal that, the bankers said, would require no cash outlay. Centerview had used a similar formula in H.J. Heinz–Kraft Foods merger under which Heinz shareholders owned 51% of the new company, Kraft Heinz. It’s not clear if the idea came from Centerview or Jacobson; Jacobson claims that Centerview introduced the concept. But Jacobson embraced it. The same day, he texted Keegan and director Ann Reese that “I threw a Hail Mary pass. The door is open and we may have a chance.” But he had effectively taken the all-cash buyout proposal off the table. Because he’d signed an NDA, and could get reports from Christodoro, Icahn soon learned about the 49.9% minority proposal, and he was anything but happy. Icahn’s position was that either Fuji paid what he called “real money,” or as Icahn puts it, “We’d gradually take business away from Fuji Xerox and eventually terminate the joint venture and take back the Xerox name in Asia,” a prospect Fuji obviously dreaded. Despite Icahn’s constant demands, it wasn’t until mid-October that talks resumed in earnest. At Jacobson’s prodding, Fuji finally hired a financial adviser, Morgan Stanley. Although Jacobson had been Xerox’s sole face in the negotiations, the board made a pivotal decision in late October: It would replace Jacobson with John Visentin, an IBM veteran who’d revitalized document outsourcer Novitex, and whom Icahn strongly endorsed. Vistentin, in fact, was to start work on Dec. 11, the deadline for Icahn to file for a proxy fight. The board also unanimously decided that Jacobson should halt all negotiations with Fuji. According to testimony from two directors, the board determined that talks should be conducted by Visentin when he took charge. On Nov. 10, Keegan, who’d just recovered from foot surgery, met with Jacobson at Westchester County Airport and told him that the board was seriously considering replacing him. According to both parties, Keegan told Jacobson that no final decision had been made. Christodoro and director Cheryl Krongard, however, insist that the board had indeed spoken. But Jacobson had an ace to play. Top executives from Fuji were scheduled for a meeting to discuss a deal on Nov. 14 in New York, and Jacobson was slated to meet with Komori in Japan on Nov. 21. When Jacobson informed Takashi Kawamura, Fujifilm’s chief of planning, that the meetings had to be canceled, Kawamura texted back that CEO Komori ”would be very disappointed” if the meetings didn’t go forward, and that the two sides “may lose the momentum of the deal.” Jacobson relayed the news to Keegan. Then came another shocking twist: Keegan reversed the unanimous decision of the board and allowed Jacobson to keep talking to Fuji. “I made a battlefield decision,” said Keegan in his testimony. Keegan’s notes show that he clearly believed that, whatever his weaknesses, Jacobson was critical to clinching the merger. Keegan told only the bankers from Centerview and one director, Ann Reese, that he’d allowed the soon-to-be-fired Jacobson to remain point man on the deal. Given a reprieve by his chairman, Jacobson was getting support and encouragement from Fujifilm. Kawamura sent chummy messages to the CEO touting their alliance against Icahn. “We should be the one team to fight against our mutual enemy,” Kawamura texted to Jacobson on Nov. 12. “We are aligned my friend,” replied Jacobson. The day before Jacobson’s meeting Komuri, Kawamura sent Jacobson a text strongly implying that Komori wanted to help protect Jacobson’s job—writing that Komori “would focus on hearing current situation surrounding you and what we can do.” Jacobson then texted Centerview’s Hess, “Kawamura told me that there is no deal without me.” At his meeting with Komori on Nov. 21, Jacobson proposed that Fuji offer a one-time dividend of $2 billion as part of the deal, hardly a big number. By keeping Jacobson, Keegan was severely antagonizing his biggest individual shareholder. Icahn was constantly calling Keegan to deliver on installing Visentin as CEO, and according to Icahn, Keegan kept saying the change was imminent. “Keegan talked and talked,” says Icahn. “He kept saying that Visentin was about to take over, but he was just stalling. Meanwhile, Jacobson is conniving behind the scenes. I wish he were half as good at running the company as he was at conniving. I’d have made a lot of money.” On Nov. 30, Fuji sent Xerox its formal offer, echoing the structure proposed in July, giving Xerox 49.9% of Fuji Xerox, and in addition, the $2 billion dividend Jacobson had suggested. Keegan presented the offer at a board meeting on Dec. 4. Most—if not all—of the directors besides Keegan and Reese were unaware that Jacobson had been meeting with Fujifilm. Several expressed shock that Jacobson had negotiated a transaction when the board had unanimously barred him from even talking to Fuji three weeks before. Because of his NDA, Icahn was cleared to track board deliberations and he quickly learned of the proposed terms of the deal Jacobson had negotiated with Fujifilm. “That’s when I blew up,” says Icahn. “Keegan keeps saying, ‘Trust me.’ Then I see the deal and say, ‘You came up with this? Are you crazy?’ He tried to flimflam me! We all agreed Jacobson couldn’t run Xerox. How’s he going to run a company twice that size?” Christodoro resigned from the board in protest on Friday, Dec. 8. His departure freed Icahn from his standstill agreement, and allowed Icahn to name a slate of four directors, which he did on Monday, Dec. 11. According to court documents, Jacobson, Keegan, and executives at Fuji were hoping that the terms would satisfy Icahn, but were also keenly aware he might bolt and launch a proxy battle. In its presentations to the board, Centerview argued that the transaction presented an excellent opportunity for Xerox to rid itself of Icahn. That’s because transactions recommended by a board almost never lose a shareholder vote. The plan was to hold both the election for directors and the vote on the deal back-to-back at the annual meeting. Shareholders would only support the Icahn slate if they opposed the deal, and according to Centerview, that was highly unlikely. Hence, the best bet was that Icahn would sell his shares before the vote, or face defeat at the annual meeting. As the proposed transaction careened forward in January, Jacobson appeared to cement his hold on the CEO post of the new Fuji Xerox. On Jan. 16, Kawamura texted Jacobson, “I clearly told Komori to tell Keegan that he wants Jeff to be CEO.” In reality, that’s not quite what Komori requested. Komori had suggested co-CEOs, one to be named by Fuji. But when Keegan demurred, Komori dropped the request. Jacobson maintains that his becoming CEO was not a condition of the deal. But in her testimony, board member Krongard stated that both Centerview and outside counsel Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison told the board that making Jacobson CEO was indeed a requirement. On the witness stand on April 27, Centerview’s David Hess, when he was asked “whether it’s correct Centerview advised the board about whether Mr. Jacobson had to be CEO of the combined company for the deal to proceed,” answered simply, “Yes.” Xerox and Fujifilm announced the merger on Jan. 31. After last-minute lobbying by Keegan, Komori had agreed to raise the dividend modestly, to $2.5 billion. Xerox’s stock traded up modestly at first, then drifted back down as investors drilled into the details. As part of the deal disclosures, Xerox for the first time published the full joint venture agreements—the poison pill. Deason went ballistic and began preparing his lawsuits. Another disclosure, too, would come back to undermine the merger. In the mad rush to complete the deal, Xerox and Fuji decided not to wait until Fuji Xerox submitted audited financial statements that put a final number on its losses from the accounting scandal. According to Xerox, the transaction’s terms stipulated that if the losses far exceeded those in the unaudited statements, Xerox could cancel the merger. On April 24, Fuji Xerox finally unveiled the audited numbers—and they showed that the losses had jumped from a preliminary estimate of $360 million to a definitive $470 million, a difference of 31%. Xerox’s loss ballooned from $90 million to $118 million. And indeed, Xerox ultimately cited the accounting imbroglio as the basis for nixing the deal. There was a final bit of drama before the merger agreement fell apart. The narrative is disclosed in the Notice of Termination that Xerox sent to Fuji on May 13. Xerox states that the accounting debacle gave it the right to cancel the deal, because Fuji Xerox both missed the deadline for submitting the audited numbers, and because those numbers diverged sharply from the original estimates. But the filing also reveals, for the first time, efforts by Jacobson to salvage the deal by getting better terms—even though Xerox was arguing publicly that the existing deal was a winner for shareholders. Jacobson lobbied for a better price during two meetings with Komori in Tokyo during March and April. And Keegan appealed to Komori by videoconference on April 24, two days before the trial began. The day after Judge Ostrager issued his decisions in favor of Deason, Keegan made further entreaties in a letter to his Komori. And on May 9 and 10, Xerox’s bankers and lawyers made their case to their counterparts from Fuji. Xerox’s request: that Fuji add $1.25 billion to the dividend, not by piling more debt on Fuji Xerox, but from Fuji’s own cash horde. That increase would have handed shareholders an extra $5 a share, or around 17%. Komori wouldn’t bite. He told Keegan he wouldn’t be available to discuss any new terms until the week of May 21. The rift grew deeper when Fuji issued a press release on May 10, stating that it had received no new proposal from Xerox, even though Xerox had been championing the extra dividend as the deal’s salvation. As Xerox states in the Notice of Termination, “That statement was clearly false. It does establish, however, Fuji’s lack of good faith.” While Fuji fumes, Icahn and Deason are celebrating their victories in court and on the board. With Visentin in place as CEO, they’re hopeful that Xerox’s results will start to improve. And with the merger off, they hope to see a true auction process for the company. If Fujifilm tries to enforce the poison pill to block a deal, it’s likely that Icahn and Deason would use the accounting scandal to challenge the move in court. Meanwhile, the two partners have a bet to settle. Fortune has learned that Icahn and Deason wagered $50,000—in cash—that Deason would lose his lawsuit to push back the deadline for nominating directors, and the Texan gladly took the bet. “I generally don’t lose a lot of bets. I guess that’s why people say never bet against Carl Icahn,” says Icahn, chuckling. “But I’m happy to lose this one.” Now he and Deason are wagering that together they can finally win big with Xerox. This article originally appeared in the June 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |