收购这家超市后,亚马逊正在努力成为零售业霸主

|

2017年6月16日早上9点,全食超市(Whole Foods)的员工纷纷挤入位于奥斯汀的公司总部大楼主层。就在一小时前,亚马逊(Amazon)宣布收购这一高端纯天然食品供应商,全食员工和公众对此都是瞠目结舌。在两家公司商谈收购的七周时间里,亚马逊积极阻止任何小道消息的泄露,而全食公司的大多数员工对即将达成的交易则浑然不知。 现在全食的员工将第一次见到他们的新主人。全食超市CEO约翰·麦基向大伙介绍了亚马逊的杰夫·威尔克,他是电商巨头亚马逊的全球消费者业务CEO,如今他已把目光对准了食品消费客户群。 “我想先说一说,全食超市如何改变了我的生活。我早上起来吃早餐,看着太阳升起在这美丽的城市——我的餐盘里有藜麦、蓝莓和其他一些蔬菜······” 这时候,素食主义的麦基(他不吃精加工食品,旅行都带着电饭锅)笑语轻盈地纠正了威尔克,“这些不全是蔬菜。”威尔克回答:“没事儿,我们正在学习。” 那一刻清晰地折射出为什么威尔克和他的团队如此需要全食超市。一句口误只是偶然,但却反映了亚马逊一直以来的一个困扰——在许多领域富有经验,但在食品行业不行。十年来,亚马逊公司——这个年销售额达到1780亿美元,且看似拥有无限资源的公司——从未在鲜食领域有过接近10亿美元的销售额。 食品领域表现乏力并不全是这个零售巨头自身的原因。生鲜食品业的生意难做是出了名的——不用说还有各种成本和物流的挑战。纽约大学斯特恩商学院的市场营销学教授斯科特·加洛维将这一问题总结为:一颗生菜的利润不到1美元,如不冷藏,保质期不超过一天,零售商要将新鲜的生菜交到顾客手里,还要赢取利润,如何做得到? 这笔137亿美元的收购给亚马逊打了兴奋剂,有望重塑价值8000亿美元的美国生鲜食品业,这是电子商务最后的、也是份额极重的待开垦领域。大约20%的零售业支出用于购买食物,但这一支出中只有2%是通过网购的。线上生鲜食品店Peapod首席市场官嘉丽·比恩考斯基认为,“生鲜食品业是电商的荒野西部,这块蛋糕巨大,还在增长。” 生鲜食品的递送困难——因为它会变质——而这恰恰是亚马逊非得要进入这个行业的原因。奶酪会发霉,肉会发臭,牛奶会变酸,所以不同于手纸或者洗洁精,消费者不能在橱柜或冰箱里长时间贮存这些鲜食。因此,每个家庭大概一周至少得去一趟超市采购新鲜食品,而没有任何其他商品会让人们消费如此之多,如此之频繁。对于亚马逊来说,进入鲜食行业是让人们的日常生活和消费习惯离不开亚马逊的关键环节。在全食超市的前联合CEO沃尔特·罗伯看来,“卖食品是卖其他一切的基础,是真正意义上的日常生活,没有任何其他品类可与之相提并论。”由此看来,亚马逊的这笔收购可不只是进入食品行业这么简单。 在零售业,亚马逊或许是最会挑事,也最富创新的公司,不过用食品作杠杆来带动销售并不是新鲜事。沃尔玛(Walmart)转型成美国最大的生鲜食品商后,也成了美国最大的零售商。在1998财年,沃尔玛全美销售额有14%来自生鲜食品。今年,随着公司年销售额达到5000亿美元,这一比例也跃升到56%。Wedbush分析师迈克尔·帕切特解释说:“是沃尔玛开了先河。”曾负责沃尔玛美国生鲜食品业务长达8年的杰克·辛克莱尔说得更明白:“人们一旦进店购买生鲜食品,他们就会东走西看,顺带买一些别的东西。亚马逊做的事情实质上跟沃尔玛一样。”而摩根大通(JPMorgan)预测,到2021年亚马逊在美国的零售额将和沃尔玛相当。 亚马逊拒绝让公司任何高管就本话题接受采访,对公众也很少谈到对于全食超市、或者更广义上的食品业的长期策略。但这一行业对于亚马逊的未来有多重要是有蛛丝马迹可寻的,比如亚马逊CEO杰夫·贝佐斯的核心圈成员之一斯蒂夫·凯塞尔——他也是Kindle团队的关键人物——现在不仅负责全食超市,还兼顾亚马逊鲜食递送业务,即承诺两小时送达的AmazonFresh和Prime Now。 观察家们认为,亚马逊收购全食超市和这一事件的前前后后——该收购的金额超过此前亚马逊收购其他公司的总额——见证了贝佐斯的远大抱负。回顾十年前,贝佐斯曾明确表示,生鲜食品业对于他的远景规划至关重要。当时他说,要成为2000亿美元的公司,亚马逊必须学会卖食品。 消费者在互联网上每花1美元就有40美分是给亚马逊的——这是一个惊人的数字,但贝佐斯似乎并不满足,因为大约85%的零售仍发生在实体店里。这位CEO掌控了我们的数字生活还嫌不够,他正试图无缝衔接线上与线下。或许将来,我们的每笔支出都会与亚马逊有关。 罗伯告诉我说:“这是里程碑式的时刻,很明显这是商业的重大变革。” |

At 9 a.m. on June 16, 2017, Whole Foods employees packed into the main level of the company’s Austin headquarters. Only an hour earlier Amazon had announced that it was acquiring the high-end natural grocer, and the corporate staffers were as shocked as the rest of the public. Amazon had been militant about leaks during the seven weeks that the two companies had been in negotiations, and the vast majority of those working inside the building had been unaware that the deal was afoot. Now they were meeting their new overlords for the first time. Whole Foods CEO John Mackey introduced Jeff Wilke of Amazon, who had flown in for the gathering. Wilke, the e-commerce giant’s CEO of Worldwide Consumer, decided to play to his foodie audience. “I wanted to tell you just a little bit about how Whole Foods changed my life as a start,” he said. “As I was sitting this morning, eating breakfast, watching the sun rise over this beautiful city—by the way, quinoa, blueberry, and some other vegetables…” That’s when Mackey, a vegan who avoids refined foods and travels with a rice cooker, lightheartedly corrected him. “Those aren’t vegetables,” he said. “That’s okay. We’re learning.” In that moment, it was clear why Wilke and his team needed Whole Foods. His comment may have been just a slip of the tongue, but it reflected a persistent issue for the company: Amazon has expertise in many areas, but food is not one of them. For a decade, Amazon—a company with $178 billion in revenue and seemingly limitless resources—had not come close to breaking the billion--dollar sales mark in its fresh food operation. The lack of progress is not entirely the retail giant’s fault. Grocery is a notoriously difficult business—and that’s before you start layering on the costs and challenges of delivery. Scott Galloway, a ¬professor of marketing at New York University’s Stern School of Business, boils the problem down to this: A head of lettuce has a ¬margin of less than a dollar and can survive outside the fridge for no more than a day. How can a retailer deliver it at peak ¬quality—and make a profit? But with the $13.7 billion acquisition, Amazon had bought itself a real shot at remaking the $800 billion U.S. grocery sector—the last frontier of e-commerce and a massive one at that. Some 20% of retail spending goes toward food, but only 2% of those sales take place on the Internet. “Grocery is the Wild West for online,” says Carrie Bienkowski, the chief marketing officer of online grocer Peapod. “The size of the prize is huge, and it’s growing.” The very thing that makes grocery delivery hard—that food goes bad—is the reason it’s so desirable to a company like Amazon. Because cheese grows mold and meat goes rancid and milk sours, consumers can’t hoard it in their cupboards or refrigerators indefinitely as they might toilet paper or laundry detergent. As a result, the average family hits the supermarket at minimum once a week; there’s nothing else you purchase or consume so much or so often. For Amazon, getting in on that frequency is critical to further ingraining itself in our routines and behaviors. “Food is the platform for selling you everything else,” says Walter Robb, the former co-CEO of Whole Foods. “It’s an everyday way into your life. There’s nothing else that happens quite that way.” Amazon’s quest is therefore about much more than just food. Amazon is perhaps the most disruptive and innovative company in retail, but using food as a lever for growth is nothing new. Walmart became the biggest retailer in the U.S. by turning itself into the nation’s largest grocer. In its fiscal 1998, 14% of Walmart’s U.S. sales came from grocery. This year, as the company hit $500 billion in revenue, that figure jumped to 56%. “Walmart pioneered this,” explains Wedbush analyst Michael Pachter. “Once you get them in the store for groceries, they walk up and down the aisle for everything else.” Says Jack Sinclair, who led Walmart’s U.S. grocery business for eight years, “The principle of what Amazon is doing is almost exactly the same.” Indeed, JPMorgan estimates that Amazon will match Walmart in U.S. sales by 2021. Amazon declined to make any of its executives available to be interviewed for this story and has said little publicly about its long-term strategy for Whole Foods—or food more broadly, for that matter. But as a sign of how critical the sector is to ¬Amazon’s future, Steve Kessel, part of CEO Jeff Bezos’s inner circle and a key figure on the Kindle team, has been brought in to run not only Whole Foods but also Amazon’s grocery delivery business, ¬AmazonFresh, and Prime Now, its two-hour delivery offering. For Amazon watchers, the company’s purchase of Whole Foods and its physical footprint—for more money than it had spent on all of its previous acquisitions combined—is a reflection of Bezos’s broader ambitions. Going as far back as a decade, Bezos has been explicit that grocery is essential to his long-term vision. In order to become a $200 billion company, he has said, Amazon must learn how to sell food. More than 40¢ of every dollar consumers spend on the Internet already goes to Amazon—an astonishing sum. And yet it appears Bezos is not satisfied leaving behind the roughly 85% of retail that still happens in brick-and-mortar stores. For the CEO, owning our digital lives is not enough. By attempting to seamlessly link both realms, Amazon has the potential to be part of every single purchase we make. “This is a monumental reference point,” says Robb. “This is clearly a revolution in the world of commerce.” |

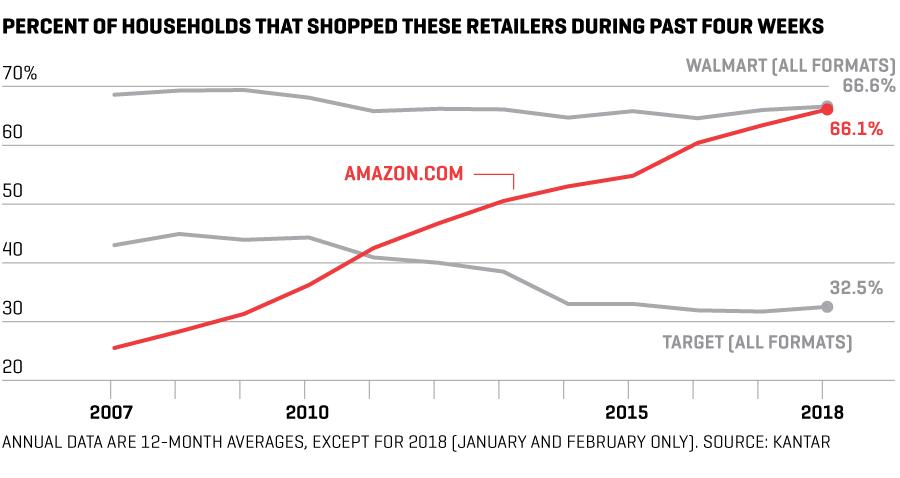

年度数据是12个月均值,除了2018年(仅1月和2月数据)。数据来源:凯度(Kantar)

|

最初亚马逊卖的是书,而书跟食品完全不同。书不会腐坏,便于运输和处置。《五十度灰》(Fifty Shades of Grey)是亚马逊网站史上最多书评的畅销书之一,而对读者来说,是到当地书店还是去巴诺书店(Barnes & Noble),或者去亚马逊网站Amazon.com买这本书,都没有什么区别。瑞信(Credit Suisse)分析师斯蒂芬·朱将书称之为“性质单一,便于处置”的产品,而在这个领域亚马逊已经胜出。如果某商品可以用纸箱运输,而购买者又不大关心商品来源,那它就是最适合亚马逊售卖的商品。 2000年中旬,亚马逊开始销售那些不易损坏的食品,比如罐装食品、饼干和曲奇,在这方面亚马逊完全胜任。曾在亚马逊工作了15年的伊恩·克拉克森说:“递送一箱Cheerios保健麦圈和一本书没多大区别,亚马逊不需要大动筋骨改造或者新建基础设施。” 生鲜食品则性质各异,处置起来困难得多。比如香蕉很容易碰坏,没有两只香蕉是一模一样的,在供应链的流程里,香蕉也在起着变化,从青涩不熟到成熟醇美,再到熟透成糊。 2007年,亚马逊还是决意尝试生鲜食品配送。客户有这个需求,而亚马逊很希望用高频率的生鲜食品订单来撬动高利润的非食品销售。亚马逊在西雅图率先发起了AmazonFresh项目,客户只需网上下单,鲜食就会递送到家。 然而亚马逊的网站并不适合人们购买食物。多数的电商交易是购买2到4件商品,买家一般定向搜索购买。而在生鲜食品店,购物者一般会左看右看,一个订单平均下来可能有50件商品。AmazonFresh的第一位全职员工克拉克森分析说:“我到今天还是这么认为——亚马逊的业务就是单件购物,客户买了需要的东西就干别的事去了。人们不会在亚马逊上买这买那来把冰箱塞满的。”在生鲜食品店,购物者这周和下周购买的商品中,有85%是一样的,所以知道购物者近期买了什么就能判断他将来会买什么。买书就是另一回事了,买一本《五十度灰》就足够了。 为了适应消费者对食品的不同购买方式,亚马逊尝试为AmazonFresh设计了一个独立网站。建这个独立网站还有另一个原因:鲜食的保质期短,亚马逊必须一个城市接另一个城市地铺开它的服务,而这并不是亚马逊的常规策略。亚马逊不能够把鲜食产品铺货到全国的网络,然后向全美推出网购服务。“传统的亚马逊品类产品就是这么干的,也赢得了市场。那么多人涌到网上购买,这个不适合生鲜食品类。”克拉克森说。 |

Books, where it all started for Amazon, are the anti-food. They never spoil and are simple to ship and handle. Fifty Shades of Grey, one of the site’s bestselling and most reviewed books of all time, is the same whether you buy it at your local independent store, at Barnes & Noble, or on Amazon.com. Books are what Credit Suisse analyst Stephen Ju calls “homogeneous, easy-to-handle” products, and Amazon has excelled at selling things that fit this criteria. If it can be shipped in a box and the purchaser cares little about whom she’s buying it from, it’s the perfect product for Amazon to sell. Nonperishable groceries like canned goods, crackers, and cookies, which the company launched in the mid-2000s, were an obvious fit. “A box of Cheerios and a book aren’t that different,” says Ian Clarkson, who spent 15 years at Amazon. “You don’t have to fundamentally rewrite or build an entirely new infrastructure.” Fresh goods, however, are about as heterogeneous and challenging to handle as it gets. Bananas bruise easily, no two are the same, and they are constantly evolving within the supply chain, going from green to ripe to mush. In 2007, Amazon decided to try fresh delivery anyway. Customers were asking for it, and Amazon was intrigued by how it might be able to leverage the frequency of grocery ordering to sell higher--margin nonfood products. The company launched AmazonFresh with a pilot in ¬Seattle in which users would place an order online, and the food would be delivered to their doorstep. Amazon’s website, however, was not well suited for how people shop for food. Most e-commerce transactions comprise two to four items, which buyers find through targeted search. But shoppers tend to browse grocery, and an order can average 50 goods. “Amazon’s business, I’d argue even today, is around a unit of one,” explains Clarkson, who was AmazonFresh’s first full-time employee. “You buy it and move on. People don’t shop to fill their fridge that way.” And in grocery, where about 85% of the items people purchase are the same week to week, what customers bought recently is highly relevant to what they’ll buy again. That’s not the case for books. One copy of Fifty Shades is enough. To cater to this different way of shopping, Amazon tried designing a separate website for AmazonFresh. The stand-alone site was necessary for another reason as well: Fresh food’s short shelf life required Amazon to roll out the service city-by-city—then an unusual launch strategy for the company. Amazon couldn’t just put products into a national fulfillment network and then turn on the web experience for the entire U.S. “That’s how traditional Amazon categories get an advantage,” says Clarkson. “You have so many people coming to the site. That doesn’t work for grocery.” |

|

在西雅图运营了6年后,AmazonFresh扩展到了加州,但它在全美的业务覆盖从未超过20个州。运营的效果喜忧参半,晨星(Morningstar)分析师R.J.霍托威说,“喜忧参半算是往好里说了。递送费用太贵,交货时间也不合适,消费者搞不明白他们下了单的食品来自哪里。”11月,亚马逊宣布在部分区域停止这项业务,但同时辩解这一举动与收购全食超市无关。 或许关键在于,AmazonFresh的规模始终不够大,使得服务上不了台阶。贝恩咨询(Bain’s Americas)零售板块负责人亚伦·切里斯分析说:“好草莓和坏草莓的主要区别不在于采购来源,而在于谁能卖得更快。AmazonFresh并没有做到这一点。” 亚马逊热衷于创建新生意,而不是收购已有的生意。但在尝试自营生鲜食品业务10年后,该考虑收购了。从开始探寻收购的可能性,到两年后收购全食超市,用切里斯的话说,“两年里亚马逊走进美国每一家生鲜食品店,试图让它们成为亚马逊的鲜食供货商。” 2017年4月,亚马逊接到全食超市的一位咨询师打来的电话,他说他看到一份报道,讲亚马逊试图收购鲜食供应链,那么见面谈一谈,有兴趣吗? 首次会面时,全食超市正在经历着动荡不安。天然和有机食品这一品类本质上是由全食建立的,但当时的市场竞争非常激烈,“全食支票”(Whole Paycheck)的声誉也摇摇欲坠。面对销售增速的放缓和萎靡的股价,全食只能做个局中人了。几周前,激进投资人Jana Partners公司透露了其在全食8.8%的股权。除了亚马逊,还有四家私募公司,甚至据报艾伯森超市(Albertsons)也对这笔交易感兴趣。 这一牵手为两家公司都解决了许多问题。对全食超市来说,亚马逊帮它从短期季度销售压力和做好长期业务的无限苦恼的循环中解脱出来。对亚马逊来说,收购全食迅即扩大了它的规模,并满足了它一直缺少的鲜食板块业务需求。物流角度看,两家公司有固定的成本,通过增量业务可以获取利润。有了全食超市稳定的业务量,亚马逊就可以构建生鲜食品业的基础设施。 除了规模增长,亚马逊也获得了更多可信度。消费者在亚马逊网站上购买的产品大多是品牌商品——索尼电视、热轮模型车、S’well牌保温杯,而生鲜食品大多没有品牌,或者有也不为人知,除了少数的几样(比如博特农庄胡萝卜和克莱门氏小柑橘)。相比之下,人们信任哪家零售商,就会去它那儿购买西兰花和西红柿。鲜食领域的这种客户信任度,亚马逊是没有的,全食弥补了这一缺点,它还给亚马逊网站的购物者讲述了种种关于食物起源的动人故事。Yummy.com(基于洛杉矶的线上线下生鲜食品店)的联合创始人和CEO巴纳比·蒙哥马利说:“在线购买食品生鲜,是个新概念。我不知道这个概念哪里来的,没见到过,也不太明白。这是件难事。”或许有线下实体店,可以让线上购买生鲜更易于让人接受。 |

After six years in Seattle, AmazonFresh expanded to California but never grew its U.S. service beyond 20 states. The results have been mixed, and “that’s putting it kindly,” says Morningstar analyst R.J. Hottovy. The service was too expensive, the delivery windows were inconvenient, and people didn’t really understand where their food was being sourced from, he says. In November, Amazon said that it was cutting service in several zip codes, a move it contended was unrelated to the Whole Foods deal. And perhaps most critically, AmazonFresh hasn’t been able to reach the scale it needs to get the service to work. The big difference between good and bad strawberries isn’t where they’re sourced from, explains Aaron Cheris, who leads Bain’s Americas retail practice; it’s who’s able to sell them faster. He says, “AmazonFresh was never able to achieve that by itself.” Amazon is partial to building businesses rather buying them. But after a decade of trying to grow its grocery operation on its own, it was time for the latter. The company started exploring the possibility of an acquisition, and spent the two years leading up to the Whole Foods deal “walking around to every grocer in the U.S. asking them to be its fresh supplier,” says Bain’s Cheris. Then, in April 2017, Amazon got a call from a consultant working on behalf of Whole Foods. The grocer had seen a report that Amazon may have been interested in buying the chain in the past. Would there be any appeal in setting up a meeting? That first rendezvous came during a tumultuous period for Whole Foods. Competition was fierce in natural and organics, the very category it had essentially created, and the grocer was struggling to shake its “Whole Paycheck” reputation. Facing slowing sales growth and a flagging share price, Whole Foods was now clearly in play. Just weeks earlier, activist investor Jana Partners disclosed an 8.8% stake in the company. In addition to Amazon, four private equity firms and reportedly supermarket chain Albertsons were among those who had expressed interest in a potential deal. The tie-up solved a lot of problems for both parties. For Whole Foods, Amazon offered freedom from the relentless cycle of short-term quarterly pressures as it tried to fix the business. For Amazon, Whole Foods gave the company instant scale and the built-in demand it had lacked in fresh food. In a logistics operation, companies have a set of fixed costs and become more profitable by layering on incremental business. Thanks to Whole Foods, Amazon now had guaranteed and predictable volume for its grocery infrastructure. Along with scale, Amazon was buying credibility. Most of the products consumers buy on Amazon are branded—a Sony TV, a Hot Wheels car, a S’well water bottle. But with the exception of a few products, such as Bolthouse Farms carrots or Cuties clementines, fresh goods don’t have brands, or at least not ones that the consumer knows. Instead, we decide where to buy our broccoli and tomatoes based on our trust in the retailer. That authority was something Amazon just didn’t have in fresh. Whole Foods supplied it—as well as providing Amazon shoppers with a more appealing story about where their food originated. “The idea of ordering groceries online is conceptual,” says Barnaby Montgomery, cofounder and CEO of Yummy.com, a Los Angeles–based online grocer with brick-and-mortar stores. “I don’t know where it comes from. I don’t see it. I don’t get it. It’s a barrier.” Having a physical place to shop turns “the conceptual offer into something more tangible.” |

|

一个尚未解决的问题是亚马逊将如何利用全食超市的483家实体店,来克服业界都觉得棘手的“最后一公里”难题——从仓储中心到消费者手中,是物流环节最后也是最昂贵的一步。有些人认为,亚马逊可以把实体店作为小型分销中心,雇人从货架上按订单取下产品,然后派送。但Marketplace Pulse(电商智能公司)的CEO和创始人尤奥扎斯·卡滋尤克纳斯表示,“这么做,理论上可行,但实践起来就难得多。仓库式的仓储跟零售仓储是完全两回事。”生鲜食品店一般会最大化利用空间,让购物者有足够空间走动,购买更多商品。而在仓库,各类商品紧密堆放,占据更大空间也更高效。对生鲜食品来说,仓库式仓储也更合适,因为过手太多影响质量。艾睿铂咨询(AlixPartners)的马修·哈默里认为,“生鲜食品每当被触碰一次,质量就下降一档。” 亚马逊目前正在多方尝试。当我用AmazonFresh在纽约下单,食品从新泽西的仓库发出,由承包商用卡车运输。同样食品用承诺两小时送达的Prime Now下单,食品从曼哈顿市中心的分销部发出,由亚马逊Flex司机(类似Uber模式,公司支付驾驶员每小时18到25美元)送达。在其他10个区域,Prime Now直接从全食超市取货。在小城市这个模式或许是敲门砖,等到达一定规模亚马逊就可以建立专门的仓库。生鲜食品业咨询师尼尔·斯特恩说,“要上规模才行。从实体店取货派送,尽管挺蹩脚的,但可以建立规模和客户群。” 未来的解决之道或许是一种混合方式:大的实体店专辟空间用于网上订单食品配送,或者实体店里包装食物选购流程自动化,但客户仍可自行选择生鲜食品。 亚马逊消费品和AmazonFresh的前任副总裁、现任某风投公司CEO的汤姆-弗菲说:“亚马逊必将疯狂实验。如果现在一切都清晰了,那倒会让我大吃一惊。” 其他行业有被亚马逊化的风险 被亚马逊搞得天翻地覆的不只是生鲜食品业。下列5个行业也得小心了。 服装业 摩根士丹利(Morgan Stanley)预测,今年亚马逊将超越沃尔玛,成为全美最大的服装销售商。亚马逊已创立几个自有服装品牌,并提供了服装订购服务。 银行业 亚马逊可以为千禧一代提供支票账户,很可能它会和一家银行合作以规避监管问题;贝恩咨询预测在未来五年,亚马逊将拥有7000万个消费者账户。 家具业 沙发和咖啡桌之类的产品,在亚马逊上的销售增长迅速。虚拟现实技术的进步,可帮助消费者评估其客厅摆家具的布局,这将促进家具网购 门票服务 Ticketmaster等提供门票服务的公司不受消费者青睐,于是该领域就给亚马逊留下了机会。到今年3月,亚马逊一直在英国提供门票销售业务,据报道亚马逊已与Ticketmaster接洽合作事宜。 快递业 亚马逊准备以其卓越的物流能力,与UPS,联邦快递以及美国邮政署竞争。华尔街日报(The Wall Street Journal)报道,亚马逊正在洛杉矶试水快递服务,称之为亚马逊快递(Shipping With Amazon)。 运营超市的平均利润率只有1%,生鲜食品业的状况怎么说都是惨淡的。为什么亚马逊会成为威胁,因为这套数学算法不适用于它。投资者们已经认可贝佐斯对短期利润的忽视。Peapod联合创始人托马斯·帕金森在去年的一个食品行业会议上说,“我们第一次碰到这样的竞争对手,亚马逊就是其中一个,他们不关心赚钱的事,这对我们是个挑战。”食品企业家格雷格·施泰尔腾波尔则认为,“亚马逊们所带来的破坏性,不在于他们有解决方案,而是他们不按这套游戏规则出牌。” 食品配送,是对传统业务模式的一种怪异的回归。20世纪初,超市兴起取代了百货店。那时候去百货店,柜台后的柜员会帮顾客从货架上抽取产品,而新型的超市模式,则要求顾客推着购物车自行取货,以换取较低的商品价格。现如今,食品配送业务的发展,不但回归到让别人帮你从货架取货那种老模式,还更进一步送货上门——高盛(Goldman Sachs)预测零售商为这项服务需支出每单22.68美元。大多数消费者都不愿为配送付钱。福雷斯特调研公司(Forrester)的分析师布伦丹·维切尔指出,“人们有一种信仰,就是不愿意为快递付费。” 尽管如此,生鲜食品业的主管们还是意识到了市场的走势。一份高盛的预测认为,到2027年生鲜食品业20%的销售将在网上进行。这一市场份额就是亚马逊的着眼点——但连锁超市也不能丢了这块市场。要下的赌注高地惊人。沃尔玛在2月公布其电商销售业务增长放缓后,它的股价创下了三十年内单日最大跌幅。沃尔玛利用其实体店,让顾客线上下单,到店取货,而在上市公司财报会议上,沃尔玛说会“加速”食品配送业务。(沃尔玛一位发言人指出,第四季度电商业务增长下滑基本是规划好的,因为公司已完成全年指标。) |

One question that remains unanswered is how Amazon will use Whole Foods’ 483 physical stores to help solve what’s known in the industry as the “last mile” problem—the final and most expensive step of the delivery process that takes a product from a central hub to its final destination. There’s some speculation that Amazon could use the stores as mini distribution centers, hiring people to pick product off the shelf to fulfill online orders that would then be sent out for delivery. “It makes sense in theory, but it’s a much harder problem than it appears,” says Juozas Kaziukenas, CEO and founder of e-commerce intelligence firm Marketplace Pulse. “The way you stock for the warehouse and retail are two different things.” Grocery stores are maximized to make customers wander through and buy more stuff. Warehouses, where random products are stacked next to each other to make the most of the space, are much more efficient. They’re also better for fresh goods because increased handling hurts quality. “Every time you touch a fresh product it degrades it,” says Matthew Hamory of consultancy AlixPartners. Right now, Amazon seems to be trying it all. When I placed an order via AmazonFresh in New York City, the food came from a New Jersey warehouse and was delivered off a truck by a contractor. When I did the same with Prime Now, which offers delivery in two hours, the goods came from a distribution facility in Midtown Manhattan and were dropped off by an Amazon Flex driver—an Uber-type model in which the company pays drivers $18 to $25 an hour. In 10 other markets, Amazon is offering Prime Now delivery directly from Whole Foods stores. That model could be a good stepping-stone in smaller cities until the company reaches enough volume to build out a dedicated warehouse. “You have to scale your way up there,” says grocery consultant Neil Stern. “Picking from a store, while crappy, is a way to establish volume and a customer base.” The future may be a hybrid approach: bigger stores that have a space carved out for putting together online deliveries. Or a store where the selection of packaged goods is automated but customers can pick out their own fresh goods. “They’re going to experiment like crazy,” says Tom Furphy, formerly a VP of consumables and AmazonFresh and now CEO of a venture capital firm. “I would be completely surprised if they have it all figured out by now.” OTHER INDUSTRIES AT RISK OF GETTING AMAZONED Grocery isn’t the only business Amazon is turning upside down. Here are five sectors that have had better watch their backs Apparel Morgan Stanley estimates that Amazon will surpass Walmart to become the biggest seller of apparel in the U.S. this year. The company has launched several private labels and a clothing subscription service. Banking Amazon could offer checking accounts aimed at millennials. It’s likely that it would partner with a bank to avoid regulatory issues; Bain estimates it could have more than 70 million consumer relationships over the next five years. Furniture Products like sofas and coffee tables are one of the fastest-growing categories at Amazon. Advancements in virtual reality that help shoppers visualize the layout of their living rooms will help push purchases online. Event Tickets With the likes of Ticketmaster getting little consumer love, this is an area ripe for disruption. Until March Amazon ran a ticketing business in the U.K., and it has reportedly had conversations with Ticketmaster about a partnership. Delivery Amazon is planning on using its logistics prowess to compete with UPS, FedEx, and USPS. The Wall Street Journal has reported that the company is testing a delivery service in Los Angeles called Shipping With Amazon. With the average supermarket operating on a 1% profit margin, the economics of the grocery industry are fragile at best. What makes Amazon such a threat is that the same math just does not apply. Investors have accepted that Bezos is uninterested in short-term profitability. “They are one of our first competitors who doesn’t really care about making money,” Peapod cofounder Thomas Parkinson said at a food conference last year, “so that’s a challenge for us.” Food entrepreneur Greg Steltenpohl puts it this way: “They’re not disruptive because they have all the answers, but because they don’t have to play by the same rules.” Food delivery is a strange reversion to an old way of doing business. The supermarket was invented in the early 20th century to replace the full-service store of the past, where a clerk behind the counter would pull products off the shelves for the customer. The new supermarket model required shoppers to push the carts and do the heavy lifting themselves in exchange for lower prices. Today, a growing segment not only wants some version of that old-timey archetype in which someone else collects the items for them, they also want them delivered to their homes—services that Goldman Sachs estimates cost a retailer $22.68 per order. That’s just not something most consumers are willing to cough up. “There’s a cultlike avoidance of paying for delivery,” explains analyst Brendan Witcher of research firm Forrester. Despite the cost, grocery executives realize that’s where the market is heading. One Goldman estimate puts 20% of the industry online by 2027. That’s market share Amazon has in its sights—and that supermarket chains cannot afford to lose. The stakes are incredibly high. When Walmart reported in February that its e-commerce sales growth had slowed, the stock took its biggest one-day dive in three decades. Walmart has been leveraging its physical locations with click-and-collect, in which customers order online and pick up their groceries at the store, but during the earnings call the company said it would “accelerate” grocery delivery. (A Walmart spokesman said the lower fourth-quarter e commerce rate was largely planned, as the company met its full-year guidance.) |

|

在这场生鲜食品业的商战中,沃尔玛的终极武器是门店多,而亚马逊的拳头是Prime。4月,亚马逊宣布其付费会员已超过1000万,而且它将提高会员年费。晨星的霍托威认为,新增会员数趋于平缓,亚马逊现在注重的是让现有会员增加支出,而不是新增会员。 收购全食超市就是明证。1010data的数据显示,在收购当时,81%的全食超市客户同时也是亚马逊客户。将全食超市纳入麾下,与其说是获取了新客户群,不如说是利用全食让亚马逊客户进一步依赖其生态系统——将全食著名的365品牌放到网上,在全食超市售卖亚马逊音箱(Echo)等产品,在全食超市设立亚马逊储物柜,便于客户取货。这种共生互利已初见成效,收购完成后,到访带有亚马逊储物柜的全食超市的顾客数增加了11%。 贝佐斯说,他的目标是要让Prime变得不可或缺,以至于不成为Prime会员就是“不负责任”。亚马逊不能没有Prime,据预测,Prime会员每年在亚马逊平均消费1500美元,比非会员每年消费额的两倍还多。艾睿铂咨询的哈默里解释:“一旦你成为Prime会员,就不需要去其他地方购物。”据知情人透露,亚马逊的目标是成为所有搜索的起点。曾任谷歌(Google)CEO的埃里克-施密特说,“很多人以为我们的对手是必应(Bing)或雅虎(Yahoo),但实际上,我们最大的对手是亚马逊。” 控制了搜索就意味着掌握了数据。亚马逊掌握了你寻找的每一个产品,你选择的每一个品类,你放入购物车又删掉的每一件商品——这就是所谓“点击流量”。现在亚马逊又推出了现实版的点击流量——Amazon Go无人便利店。这家位于西雅图的无人店使用高架摄像头和货架内的重量传感器来追踪购物行为,消费者拿完商品直接走人,甚至不需要结帐。 亚马逊对全食超市也有类似的安排吗?或许安排在低价的365门店,但专家们怀疑这种“拿了就走”的模式是否标志着行业前沿。全食超市的一项重要资产是高品位——客户的感官、视觉感受和购物体验俱佳。这是一个重要的卖点,在这个时代,平庸寡淡的零售店已经倒闭或正在倒闭。 在贝佐斯一直期望创建的包罗万象且流畅无比的零售体验中,门店是其中一环,而亚马逊的虚拟助手Alexa以及Echo音箱则是另一环。维切尔认为,“未来购买生鲜食品就是动动嘴——送些食品来,加点大蒜,不要西红柿。亚马逊正在一步步地实现这一切。”加拿大皇家资本市场(RBC Capital Markets)预测,到了2020年,有1280万户家庭会使用Alexa, 他们在亚马逊上的消费会增长10%。 “一朝成为Prime会员,无虑其他” 艾睿铂咨询马修·哈默里 亚马逊还有一记绝杀,纽约大学的加洛韦称之为“零点击环境”,在这一环境下的重复购买行为——大部分零售是重复购物——不是结束在门阶,而是结束在你的橱柜或者冰箱。部分地区的Prime会员使用包含监控探头、智能锁和一个手机app的亚马逊钥匙系统(Amazon Key),就能让包裹递送进家门。亚马逊在4月收购了智能门铃公司Ring,让加洛韦的预言更近成真。他说:“很难想象有了这些的亚马逊会干出什么。” 无论你认为这听起来有点乌托邦或者是反乌托邦,那只是因为视角不同。但亚马逊也有不小的风险,因为人们最终会觉得这家公司知道太多关于我们的信息,或者操控了太多我们的生活,亚马逊带来的所有便利结果反而让人们不舒服。不信问问马克·扎克伯格吧,他刚刚因为Facebook的隐私泄露和安全问题去国会山作证了。 食品业务可能成为亚马逊的转折点之一。过去几年里,随着人工智能和机器学习的兴起,科技世界大步前进,而食品行业却反其道而行之,走向农业的非产业化。在加州大学伯克利分校领导食品风险实验室项目的威廉·罗森茨威格认为:“追求健康和可持续的食品行业与亚马逊模式是不协调的。我担心亚马逊的文化里没有食品的基因。便捷、低价和快速——这些不是食品行业的价值观和核心竞争力。” 在便捷性与更多关注客户之间亚马逊该如何取舍?这个问题恐怕Alexa也还没有答案。(财富中文网) 译者:Hank |

Walmart’s ultimate weapon in the grocery wars is its massive store footprint; Amazon’s is Prime. In April, Amazon announced that the membership service had exceeded a whopping 100 million paid subscribers and that it would increase its annual fee. Morningstar’s Hottovy thinks that the market for new members may be plateauing, and that Amazon is now focused on increasing what current Prime users spend rather than recruiting new ones. The Whole Foods deal was a case in point. According to 1010data, at the time of the acquisition, 81% of Whole Foods customers were already Amazon shoppers. So rather than capturing a new base, adding Whole Foods to the portfolio served as a tool to further ingrain Amazon customers within its ecosystem—offering Whole Foods’ popular 365 private label online, selling products like the Amazon Echo in its stores, and setting up Amazon lockers within Whole Foods for customers to pick up packages. Already, the symbiosis is at work. Since the deal closed, quick visits to Whole Foods were up 11% in stores with Amazon lockers. Bezos says his aim is to make Prime so essential that it’s “irresponsible” not to join. And its value to the company is unmissable: By some estimates, Prime members spend an average $1,500 a year on Amazon, more than twice as much as non-Prime users. “Once you’re a Prime customer, you don’t go anywhere else to look,” explains AlixPartners’ Hamory. The goal, say insiders, is for Amazon to be the place where you start all of your searches. “Many people think our main competition is Bing or Yahoo,” Google’s onetime CEO Eric Schmidt has said. “But, really, our biggest search competitor is Amazon.” Capturing search means capturing data. Amazon knows every product you look for, every category you choose, everything you put in your cart then abandon—what’s known as the “clickstream.” Now the company is trying to capture the real-life version of the clickstream with Amazon Go. The Seattle store uses overhead cameras and weight sensors in shelves to track shoppers so closely that they can simply leave the store when done shopping—no need to check out. Might Amazon have something similar planned for Whole Foods stores? Perhaps in its lower-priced 365 locations, but experts are skeptical that the “just walk out” experience is coming to flagship outposts. One of Whole Foods’ assets is that it is high-touch—sensory, visual, and experiential. That’s a major selling point in an era where boring, mediocre retail is dead or dying. The stores play one part in the all-encompassing, frictionless retail experience that Bezos has long aspired to create; Alexa, Amazon’s virtual assistant, and its Echo speaker devices play another. “The future of grocery shopping is most likely the ability to say, send me groceries, add garlic, remove tomatoes,” says Witcher. “Amazon has put the pieces in place to actually make it happen.” RBC Capital Markets predicts that by 2020, 128 million households will be using Alexa, driving a 10% increase in their Amazon spending. “Once you’re a Prime customer, you don’t go anywhere else.” Mathew Hamory of consultancy AlixPartners Another aspect of Amazon’s end-game is what NYU’s Galloway calls a “zero-click environment” in which recurring purchases—the majority of retail—end up not just on your doorstep but in your closet or fridge. Prime members in some locations can already get packages delivered inside their homes with Amazon Key, which includes a security camera, smart lock, and app. Amazon’s April acquisition of smart doorbell company Ring makes Galloway’s vision even more likely. “It’s staggering to think about what they could do with that,” he says. Whether this sounds utopian or dystopian is a matter of perspective. But there is no small risk to Amazon that people eventually begin to feel like the company knows too much or controls too much of their lives, that they become uncomfortable with the consequences of all of this convenience. Just ask Mark Zuckerberg, who recently testified on Capitol Hill over Facebook’s privacy and security issues. Food could be part of that tipping point for Amazon. For the past few years, as the tech world has been making strides with artificial intelligence and machine learning, foodies have been moving in the opposite direction, pushing to deindustrialize the agricultural system. “Healthy and sustainable food is incoherent with the Amazon model,” says William Rosenzweig, who leads the Food Venture Lab program at UC–Berkeley. “I worry that the culture of Amazon doesn’t contain that gene set. Convenience, price, and speed—those are not the right values or core competencies of food.” Can Amazon learn to walk that delicate line between convenience and care? That’s something that not even Alexa can answer yet. |