这500家公司占到美国经济总量的三分之二,美国人应该害怕

|

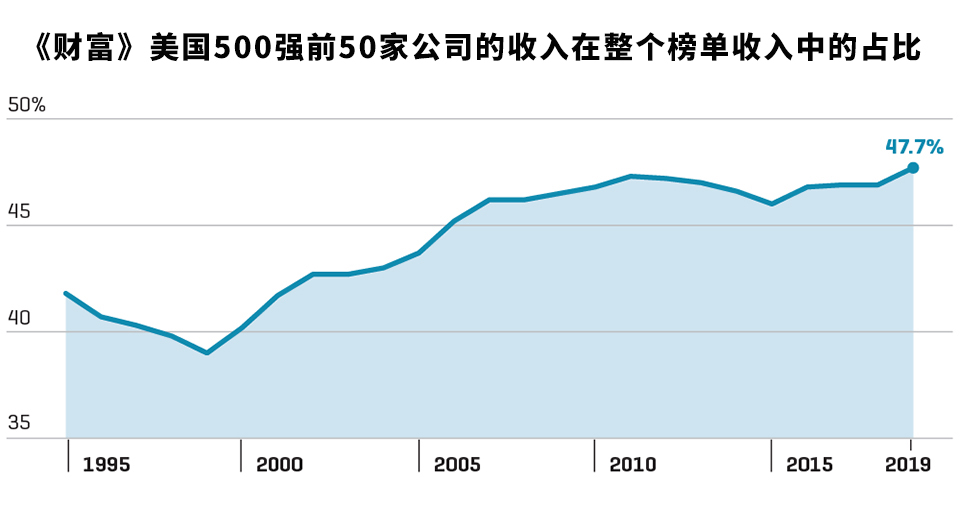

大家都知道,在美国这几十年的经济增长中,极少数最富有的人不成比例地享受了大量的经济增长成果。这种现象在美国企业界中也同样存在。越来越多的收益被相对少数的大企业所攫取,它们就是所谓的“企业巨头”。 只需看看《财富》美国500强榜单,你就知道这个问题的严重性了。去年,美国最大的500家公司的收入达到创纪录的13.7万亿美元,相当于美国经济总量的三分之二以上。而在这13.7万亿美元中,又有47.7%属于榜单上的前50家公司。这个比例在去年是46.9%,15年前是43.7%,1995年是41%。 考虑到当前的经济业态越来越取决于巨头间的角力,说不定到明年,这个比例就会提高到50%。比如连锁药业巨头CVS Health(今年排名《财富》美国500强第8位)去年年底吞并了安泰(美国最大的保险公司之一,去年在《财富》美国500强上排名第49位),更加成了医疗保健市场上横扫一切的存在。 美国电信巨头AT&T(第9名)则以313亿美元吃掉了娱乐业的时代华纳(《权力的游戏》的发行方HBO、特纳广播公司、华纳兄弟公司等都是时代华纳的旗下产业)。去年,时代华纳在《财富》美国500强上的排名是第98名。而排名第31位的马拉松石油公司则收购了排名第100位的炼油公司Andeavor。 在一个鼓励创新和商业头脑的经济中,这种现象是否正常?抑或是还有更加值得担忧的趋势等着我们? 就行业集中化现象,也就是行业被少数大企业垄断的现象,经济学家们给出了各种原因,不过他们普遍同意各行各业的集中化程度在加强——就算你不是经济学家,也不难注意到这一点:你原来可能在来德爱(Rite Aid)的药店买药,现在却只能去沃尔格林(Walgreen)了。你现在出门也买不到美国航空或大陆航空的机票了。但是你的所有东西——包括全食超市的食品,基本上都是在亚马逊网购的。 波士顿大学的经济学家詹姆斯·贝森是研究行业集中化问题的专家。他表示:“毫无疑问,行业集中化现象在全国范围内都在增强。”贝森表示,信息技术在这个过程中扮演了重要角色。有些公司投入重资打造了专有软件(当然,这样做的通常也是那些业内最大的公司),它们显然已经成了当前经济的赢家,效率、销量和人力规模都实现了增长。 |

It’s well understood in the United States that in recent decades, the spoils of the nation’s economic growth have gone disproportionately to the wealthiest few. But a similar phenomenon exists among U.S. corporations. More and more of their collective revenues are concentrated in a relatively small number of large firms: the corporate giants. Look no further than the Fortune 500 in this issue. Last year, America’s 500 largest corporations tallied a record $13.7 trillion in revenues, a figure equivalent to more than two-thirds of the U.S. economy. Of those trillions and trillions of sales, 47.7% of them belonged to the list’s top 50 firms, up from 46.9% last year, 43.7% 15 years ago, and 41% in 1995. It’s quite possible that next year they’ll account for a solid half, given recent developments in this land of giants: CVS Health, the drugstore chain–cum–pharmacy benefits manager (No. 8 this year), late last year gobbled up Aetna, which as one of America’s largest insurers ranked No. 49 on the Fortune 500 in 2018. AT&T (No. 9), meanwhile, swallowed up Time Warner, a $31.3 billion morsel from the entertainment industry (HBO, Turner Broadcasting, Warner Bros.) that ranked No. 98 last year. And Marathon Petroleum (No. 31) scooped up Andeavor, a Fortune 100 oil refinery. Is this the natural evolution of an economy in which innovation and business acumen are duly rewarded? Or are there more worrisome forces afoot? Economists cite varying reasons for increasing industry concentration—the extent to which industries are dominated by a few large firms—but agree it’s on the rise. (One need not be an economist to notice: Your Rite Aid is now a Walgreens; you can no longer fly US Air or Continental; you buy almost everything—including your Whole Foods groceries—from Amazon.) “It’s unmistakable that concentration has been growing at a national level,” says James Bessen, an economist at Boston University whose research has looked at why the top tier of companies is pulling ahead of the pack. Bessen points to the role of information technology. Firms that have invested most heavily in proprietary software (incidentally, often the biggest firms) have emerged as clear winners in the current economy, experiencing productivity, sales, and labor force gains, he says. |

|

耶鲁大学的经济学教授菲奥娜·斯科特·莫顿曾经在美国司法部的反垄断部门工作过。莫顿指出,数据本身就有一种“天生的聚集效应”。掌握了大量数据的公司,可以较低的成本实现规模经济,并进一步受益于它的反馈和网络效应,从而实现良性循环。换句话说,你拥有的数据越多,你的产品对客户就越好、越有吸引力。

虽然科技和数据重新塑造了经济的形态,但在这个过程中,包括莫顿在内的很多专家都认为,美国的反垄断执法几乎已经形同虚设——曾几何时,美国反垄断部门还是阻挡过很多大企业的合并的,为促进经济创新立下过汗马功劳。“现在我们已经倒退了起码40年,同时,行业集中化趋势却在迅速发展。”

宾夕法尼亚大学的法学教授、反垄断专家赫伯特·霍文坎普指出,在行业集中化愈演愈烈的同时,各种保护大企业垄断地位的反竞争行为也越来越常见。比如一些公司强迫员工签订非竞争性合同,使各级员工甚至连普通员工也很难换工作,从而有效地压低了工资。霍文坎普还指出,大型科技公司往往在潜在竞争对手刚一出现时就收购它们。比如亚马逊在2010年收购了Diapers.com的母公司Quidsi。“这些初创公司在成为一个强有力的竞争对手前,就被他们收购了。”

那么,我们应该担心这些问题吗?经济学家们警告道,一个头重脚轻的经济,会让社会付出巨大成本。大量经济资源集中在相对少数人手中,会导致产出下降、价格上涨、消费者的选择减少、创新受到抑制。另外,少数人的经济实力往往会转化为政治力量,让既得利益者能够进一步巩固自己的地位。

各行各业的集中化现象,也引起了不少人的关注,并且引发了一系列的反垄断运动。人们的注意力主要集中在大型科技公司身上。从伊丽莎白·沃伦到Facebook的联合创始人克里斯·休斯,几乎所有人今年都在呼吁Facebook分拆业务。另外CVS收购安泰案也并未尘埃落定。今年4月,也就是美国政府批准这笔收购案的几个月之后,一名联邦法官表示,他想听听反对合并的各方的意见。他表示:“这件事对很多人都将产生极大的后果。”(财富中文网) 本文的另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2019年6月刊,标题为《巨人之地》。译者:朴成奎 |

Fiona Scott Morton, an economics professor at Yale who once worked in the Department of Justice’s antitrust division, homes in on the role of data, which she says “has a natural concentrating” effect. Data-rich companies can achieve economies of scale cheaply and further benefit from feedback and network effects—the more data you have, the better and more attractive to customers your product becomes, she explains.

As technology and data have reshaped the economy, she and others argue that antitrust enforcement—which may have blocked mergers of big players and helped spur innovation in the past—has all but disappeared. “We’ve been walking backwards at least 40 years, at the same time that there’s been this springing forward.”

Meanwhile, anticompetitive practices protecting the position of the largest firms have proliferated, adds Herbert Hovenkamp, a law professor and antitrust expert at the University of Pennsylvania. He points to the conduct of large firms that force employees into noncompete agreements, which effectively suppress wages by making it difficult for even rank-and-file workers to change jobs. He also singles out the tendency of Big Tech to buy up potential competitors as soon they come along: like Amazon snapping up Quidsi, the parent of Diapers.com, in 2010. “These startups are acquired before they can ever emerge as vibrant competitors themselves.”

Should we be concerned about all this? Economists warn there are significant costs to a top-heavy economy, in which the lion’s share of financial resources are concentrated into the coffers of a relative few: lower output, higher prices, reduced choice, and stifled innovation. Plus, that economic might often translates into political power that can enable the leaders to entrench themselves even further.

That the biggest corporate giants keep getting bigger has drawn notice, inspiring a burgeoning anti-monopoly movement. Much of the attention is focused on Big Tech; everyone from Elizabeth Warren to Facebook cofounder Chris Hughes has called for the breakup of Facebook this year. But the book might not be closed on CVS either: In April, months after the government approved its merger with Aetna, a federal judge ruled that he wanted to hear from parties that opposed it. “This is a matter of great consequence to a lot of people,” he said.

A version of this article appears in the June 2019 issue of Fortune with the headline “In the Land of Giants.” |