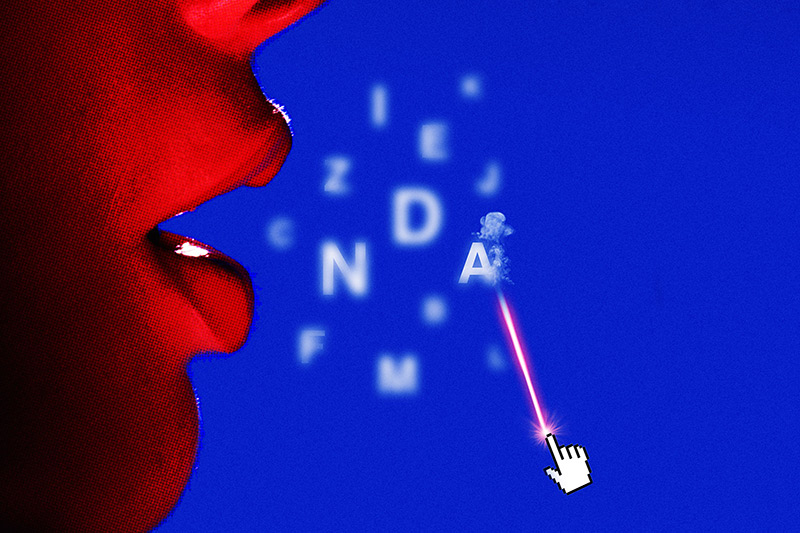

科技公司爱签保密协议,这可不是好事

|

在接受硅谷公司的入职邀请后,可能会被要求签一份保密协议。这些被学者们戏称为“沉默合同”的文件以前只要求高管签署,而今它在科技界却像羊毛背心一样随处可见。

在谷歌、苹果公司和亚马逊等企业,所有低级别员工和承包商估计都要签保密协议,供应商和访客也不能例外。这种合同通常不会具体说明违约赔偿金额,但有一点说的很清楚,那就是话太多的人可能会遭到起诉,不管他讲的是别人的工资还是管理者的奇怪行为。

在科技行业最近出现的一系列争议性事件中,保密协议都处于核心位置,这让人们开始质疑其数量的激增和覆盖范围。虽然企业方面坚持说有必要签署这样的协议,但批评人士指出,在它们的威吓下,人们都不敢提及科技行业的阴暗面。

当性骚扰指控在Uber等公司掀起波澜时,一些科技从业者表示保密协议让受害者无法直言不讳。当血液检测初创公司Theranos的员工越发怀疑高层在骗人时,他们却不敢公开发出警告。

今年2月,科技新闻网站The Verge刊登的一篇文章讲述了时薪15美元的管理员们尽力为Facebook清理色情内容、暴力威胁和骚扰后感觉很受伤的故事,但所有当事人都不同意使用自己的真实姓名,原因也是保密协议。

情况并非一直如此。据从事保密协议研究的圣地亚哥大学法学教授奥利·洛贝尔介绍,这种协议在20世纪70年代流行起来,科技公司把它作为保护商业秘密的手段,而且这仍然是他们口中的主要目的。但从那以后,保密协议开始变成了控制员工和压制批评的全能大棒。

洛贝尔说,近几年公司甚至开始用保密协议来防止员工公开自己的薪酬,这是控制工资的妙招。这样的封口令可能还会阻碍女性和少数族裔曝光自己在酬劳方面受到的不公平待遇,而且直到最近,许多科技公司仍然在淡化这个问题。

她指出:“公司试图向员工发出的信号是所有东西都碰不得,都是公司专有的。”

这样的局面可能不会在短时间内发生改变。虽然法律专家建议法官将许多覆盖范围宽广的保密协议认定为不可执行,而且美国联邦法律保护员工谈论工作环境的权力,但这个问题几乎没有在法庭上受到过考验。原因显而易见。

韦德纳大学的法学教授艾伦·加菲尔德长期以来一直在批评保密协议,他说:“这些协议有恐吓别人的作用。也许你有很好的公共政策诉求,但谁想冒险让那些厉害的律师威胁说要起诉自己呢?”

当然,保密协议并非不可撼动。加菲尔德提到了最近的“一些大坝决口”事件。比如去年,Uber在压力之下不再要求涉及性骚扰事件的员工接受私下仲裁或另行签署保密协议。批评人士一直将这些做法和这家科技公司滥用保密协议联系在一起。

不过,这样的事只是少数。对Facebook、谷歌、苹果和亚马逊等公司来说,它们尽量扩大保密协议覆盖面的动力异常充足。这些公司均拒绝或尚未就本文发表评论。就算这样的协议在法律上站不住脚,闹到法庭上的可能性也非常小,而且即使让人签了最夸张的保密协议,也不会受到惩罚。同时,虽然即将入职的员工可以在谈薪水时要求降低保密协议的约束力,但只有最勇敢(或最愚蠢)的人才会这样做。

由此产生的结果就是,到目前为止,或许必须得由政界头面人物发起对保密协议使用情况的核查。按照这样的思路,美国各州的总检察长已经开始锁定限制跳槽员工的不正当竞业禁止协议,而且理论上,如果公司将保密协议用在保护真正商业机密以外的地方,立法者就可以对其施以惩罚。

加菲尔德和洛贝尔都指出,旨在提高透明度并让人畅所欲言的法律还包括举报人保护法和所谓的反对针对公众参与的策略性诉讼法案(通常会让可笑的诽谤诉讼目标收到律师费)。但这样的改革需要时间,也就是说科技公司仍然会要求所有入职人员签署保密协议。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2019年5月刊,标题为《别告诉任何人》。 译者:Charlie 审校:夏林 |

Accept a Job at any Silicon Valley company, and chances are someone will ask you to sign a nondisclosure agreement. These documents, dubbed “contracts of silence” by academics, were once only required of senior managers, but today they are as common in the tech world as fleece vests.

At companies like Google, Apple, and Amazon, every low-level employee or contractor is expected to sign an NDA, and so are vendors and visitors. The contracts typically don’t specify a dollar figure for violating the terms, but they do make one thing clear: Anyone who talks too much—about anything from their salaries to their manager’s weird behavior—may be sued.

NDAs have played a central role in a number of recent tech industry controversies, raising new questions about their proliferation and scope. While businesses insist the agreements are necessary, critics say they scare people from talking about the darker sides of the industry.

When sexual harassment allegations roiled companies, including Uber, some tech workers blamed the agreements for preventing victims from speaking out. When employees at blood-testing startup Theranos grew suspicious about potential fraud by executives, they feared sounding the alarm publicly.

In February, tech-news site the Verge published an article about how Facebook moderators earning $15 a hour felt traumatized after trying to cleanse the service of porn, violent threats, and harassment. None would agree to reveal their real names, citing their NDAs.

It wasn’t always this way. According to Orly Lobel, a University of San Diego law professor who studies the agreements, NDAs became common in the 1970s as a way for tech firms to protect trade secrets, and that remains their main stated objective. Since then, however, they’ve morphed into an all-purpose cudgel to control employees and suppress criticism.

In recent years, Lobel says, companies have even started using them to prevent employees from publicly disclosing their salaries—a subtle attempt to cap wages. The muzzle could also thwart women and minorities from exposing unequal pay, a problem that many tech companies have, until recently, downplayed.

“The companies are trying to signal to employees that everything is off-limits and is proprietary,” says Lobel.

This situation is unlikely to change anytime soon. While legal experts suggest judges would declare many broad NDAs unenforceable, and federal laws protect employees’ right to discuss working conditions, the issue has barely been tested in court. The reason is obvious enough.

“These agreements have the effect of terrorizing people,” says Widener University law professor Alan Garfield, a longtime critic of NDAs. “Maybe you do have a good public policy claim, but who wants to risk having high-powered lawyers threatening to sue you?”

NDAs are not impregnable, of course. Garfield points to recent “breaches of the dam.” Under pressure last year, for example, Uber stopped requiring employees to enter private arbitration or sign separate NDAs in cases involving alleged sexual harassment, practices critics had linked to tech’s overuse of NDAs.

However, such examples are outliers. As for companies like Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon, all of which declined to comment for this story or did not respond, they have every incentive to impose NDAs as widely as possible. Even if the contracts are on shaky legal ground, the possibility of a court challenge is remote, and there is no punishment for asking people to sign even the most outlandish NDAs. And while prospective employees could demand less restrictive NDAs as part of their salary negotiations, only the most brave (or foolish) would do so.

The upshot is that, for now, any checks on the use of NDAs may have to come from political leaders. In the same way that state attorneys general have begun to target the misuse of noncompete agreements that limit employees when switching jobs, lawmakers theoretically could punish companies that use NDAs for anything other than protecting bona fide trade secrets.

Both Garfield and Lobel also point to whistleblower laws and so-called anti-SLAPP statutes (which typically let targets of frivolous libel lawsuits collect attorney fees) as other examples of legislation aimed at promoting transparency and free speech. Such reforms take time, however, meaning tech companies will continue to require NDAs of all comers.

A version of this article appears in the May 2019 issue of Fortune with the headline “Don’t Tell Anyone.” |