全球劳动者对经济增长的贡献在不断下降,自动化主因?

|

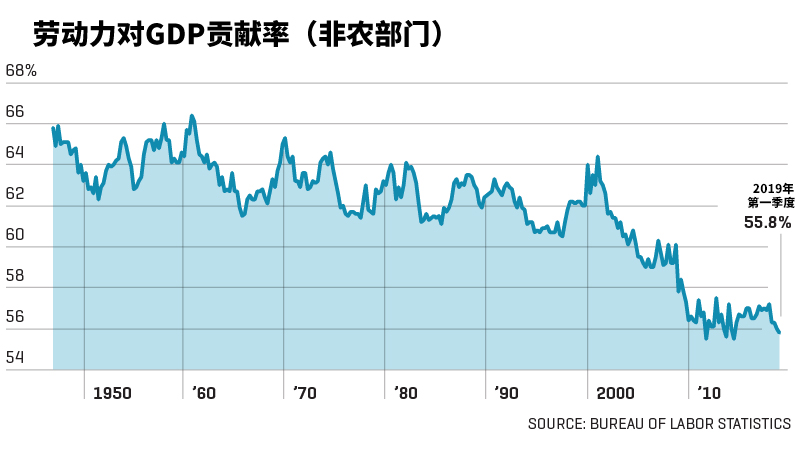

为什么劳动者对整体经济产出的贡献率正在下滑?这是一大谜题。如果你认为情况历来如此,或者答案显而易见,那你就错了。相反,历经过去两个世纪的繁荣、萧条、战争和科技革命,劳动力对GDP的贡献在大部分时间里都保持了相当程度的稳定(美国约为65%)。这个结论在几十年前第一次被发现时,震惊了每一个人。英国经济学家约翰·梅纳德·凯恩斯称这“有点像个奇迹”。尽管如此,它看起来是个不争的事实——劳动者的薪水会随着GDP一起增长。 不过,当然,这个事实并非不可改变。从20世纪80年代开始,全球劳动力对GDP的贡献开始下滑。从2000年起,它的下滑速度进一步增加。目前美国劳动力对GDP的贡献仅有56%,如果与65%的情况进行对比,相当于平均每个家庭的年收入减少了1.1万美元。在一些国家,劳动力对GDP贡献率的减少更加突出,尤其是德国,而中国、印度、墨西哥等发展中国家也呈现出这一现象。 所以这究竟是怎么了?首要嫌疑犯是技术,不过这种因果关系没有看起来那么明显。毕竟,19世纪的技术进步是革命性的,它们极大地提升了生活水平。而过去30年里技术和财富分配的关系有什么变化? 麻省理工学院(MIT)的达龙·阿西莫格鲁和波士顿大学(Boston University)的帕斯奎尔·雷斯特雷波在最近的研究中,以一种全新的方式来分析技术对劳动者施加了何种影响,令人大开眼界。他们指出,自动化总是会淘汰一些岗位,但技术也会创造出新的岗位,例如在19世纪,机械取代了大量农工,却也创造出了数百万个制造业的新岗位。这一点可能众所周知,但关于技术所淘汰和创造出的工作的综合数据却无处可查。 所以,研究人员做了大量数值计算,得出了结果。阿西莫格鲁表示:“看看第二次世界大战之后的40年,”这段时期,劳动力对GDP的贡献率仍旧保持稳定。“在此期间自动化(淘汰的工作任务)相当多,但也创造出了很多新任务,两者几乎相等。”(想想服务业的那些新岗位,它们在20世纪50年代和60年代在美国经济中占据的份额大了许多。)“而过去30年里,情况发生了变化,自动化的速度更快了一些,但新任务的引入却非常、非常慢。这是一个令人吃惊的发现。” 这也是一大谜题。这项研究的重要推论是:自动化未必对所有劳动者都有好处,这在现代史上还是头一遭。阿西莫格鲁和雷斯特雷波写道:“我们的证据和概念研究”并不支持“技术变革总是时时处处地造福劳动者的假设。如果未来生产力增长的来源依旧是自动化,劳动力的相对地位将会下降。” |

Here’s a mystery: Why is workers’ share of total economic output declining? If you think that’s been happening forever or that the answer is obvious, you’d be wrong. On the contrary, through most of the past two centuries of booms, busts, wars, and technological revolution, labor’s share of GDP stayed remarkably constant (around 65% in the U.S.). That finding, when first unearthed decades ago, surprised everyone. British economist John Maynard Keynes called it “a bit of a miracle.” Nonetheless, it looked like a fact of life—workers’ pay grows with GDP. But then, of course, it didn’t. Starting in the 1980s, around the world, labor’s share began to fall slowly. In 2000, it began to fall quickly. Labor share is now 56% in the U.S., which translates into some $11,000 less in annual income for the average household than with a 65% share. The decline has been even steeper in some countries, notably Germany, and has occurred also in developing economies, including China, India, and Mexico. So what’s going on? The leading suspect is technology, but the causal relationship isn’t as obvious as it may seem. After all, the tech advances of the 19th century were revolutionary, and they improved living standards dramatically. What has changed in the past 30 years about the relationship between technology and wealth distribution? Recent research by Daron ¬Acemoglu of MIT and Pascual Restrepo of Boston University outlines an eye-opening new way of analyzing technology’s effects on workers. Automation always eliminates jobs, they note, and technology also creates new jobs; machinery displaced a lot of farmworkers in the 19th century but also created millions of new jobs in manufacturing, for example. That may be common knowledge, but comprehensive figures on tasks eliminated and created by technology were not readily available. So the researchers did some heavy-duty number crunching and found them. “Look at the 40 years after World War II,” says Acemoglu, referring to a period when the labor share was still holding steady. “There was quite a bit of automation [that eliminated tasks] but also quite a bit of introducing new tasks—they were almost identical.” (Think of all the new jobs in services as they became a much larger part of the U.S. economy in the 1950s and 1960s.) “Then the sea change in the last 30 years—automation gets a little faster, but the introduction of new tasks gets very, very slow. That’s the big headline finding.” It’s also the mystery. The significant implication of this research: For the first time in modern history, automation isn’t necessarily good for workers overall. “Our evidence and conceptual approach” do not support “the presumption that technological change will always and everywhere be favorable to labor,” Acemoglu and Restrepo write. “If the origin of productivity growth in the future continues to be automation, the relative standing of labor will decline.” |

|

这里又要问,为什么?对观察周遭世界的非经济学家而言,很难不得出技术的影响力日益增大的宏观解释——包括摩尔定律、高级算法、通用连接,一切的成本都达到了历史新低。也许技术已经跨越了一些与人类能力相关的门槛。如果真是如此,资本就不会像以前一样用技术增强劳动力,而是有动机完全取代它。非自动化的岗位数量,无论是现存的还是目前还无法想象的,都会有所减少。牛津大学(Oxford University)的丹尼尔·萨斯坎德基于这样的新资本形态建立了一个完全取代劳动力的经济模型,称其为“先进资本”。这一模型最后推断出了一个“工资削减为零”的场景。 实际上,其他研究人员并没有对此做好准备。不过,技术让劳动者的生活变得更好,也让他们的必要性有所降低——这种观点正在日益变得主流,也体现了自动化对劳动力的影响已经有了翻天覆地的变化。企业和政府领导人、投资者和劳动者都需要转变观念。选民可能需要公共政策来限制技术对劳动者的影响,因为我们无法指望技术来提高劳动者整体的福祉。 在2013年的一次演说中,前美国财政部部长劳伦斯·萨默斯表示:“这一系列发展会定义我们这个时代的经济特征。”看起来,这句话每天都在更加接近现实。如今已经处于大型社会重组的早期阶段。准备好迎接动荡吧。(财富中文网) 本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2019年7月刊,标题为《自动化的财富转移》。 译者:严匡正 |

Again, why? For noneconomists observing the world around us, it’s hard not to conclude that the big-picture explanation involves technology’s increasing power—a combination of Moore’s law, advanced algorithms, and universal connectivity, all at ever-falling cost. Maybe tech has crossed some threshold relative to human capabilities. If so, capital wouldn’t augment labor with technology, as it has always done, but sometimes would have an incentive to fully substitute for it. The number of non-automatable jobs, existing or still unimagined, would dwindle. Daniel Susskind of Oxford University has proposed an economic model based on a new type of capital along these lines, “advanced capital,” that is purely labor-displacing. His model leads to a scenario in which “wages decline to zero.” Virtually no other researcher is ready to go there. But the increasingly mainstream view—that technology can still make workers better off but doesn’t necessarily—reflects a world-changing shift in the way automation affects labor. It requires new assumptions by business and government leaders, investors, and workers. It suggests that voters may demand public policy that controls technology’s effect on workers, since tech can’t be counted on to boost workers’ well-being overall. In a 2013 lecture, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers said, “This set of developments is going to be the defining economic feature of our era.” That’s looking truer every day. A major societal realignment is in its early stages. Brace for the tumult. A version of this article appears in the July 2019 issue of Fortune with the headline “The Shifting Fortunes of Automation.” |