新药在商业失败了,就不再有价值了吗?

|

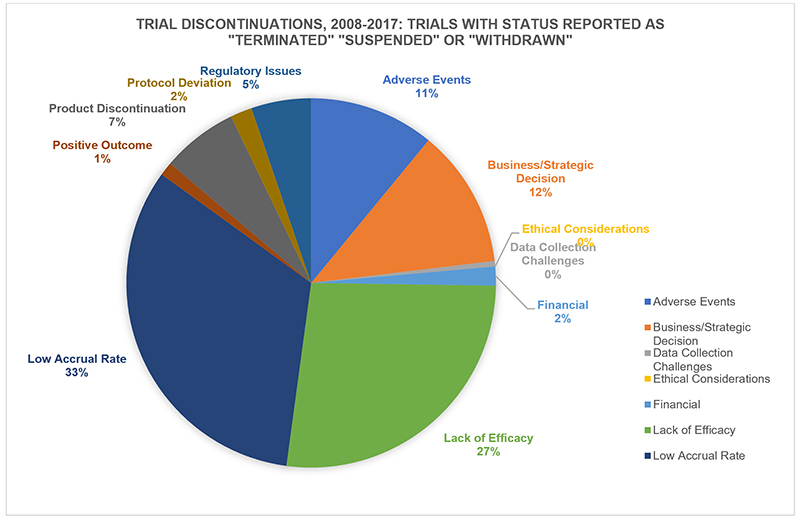

对于制药行业来说,失败是一件不可避免的事。没有一次次的失败,我们就不可能知道人工干预健康或疾病是一件多么困难的事。因此,我们预期的目标不断因为各种意外而落空,也就不是什么奇怪的事了。 在制药行业,“失败”这个词既被滥用了,同时也没有得到足够的重视。乍一看,这似乎是显而易见的。当失败发生时,大家的借口都是:“我们努力了,但没有成功。” 为什么会有这么简单的失败观?这与对我们对药品研发的成功率,以及对新药成功上市的难度(以及成本)的一般估计不无关系。新药开发的成功率会直接影响到行业“保护创新”的需求。假设在当前体制下,我们每年只能够上市40到50种新药。徜若我们又降低了这个成功率,会发生什么呢? 制药企业一提起“损耗”一词,就好像损耗总是巨大的、不可避免的且不可预测的。不过我们不妨设想一下,如果有一名服务员,他在给你上菜的过程中,连续打碎了4个盘子,第5盘菜终于没有打碎,不过他却可以理直气壮地把前面4盘菜的价格也算到你的饭钱里,那他还有什么动机去练习上菜的技术呢? 乍一看,这个类比似乎站不住脚——这些菜已经做出来了,并且交到了服务员的手上,并非没有做出来。不过如果这位服务员觉得这些菜不值得给客人上,因此决定将它们留在厨房里,又会发生什么呢?(当然,你还是得给所有这些没有上的菜付钱。) 就这一点,我们从药物第三期临床试验的失败数据中,可以看出一些有意思的东西——第三期临床试验也是药物测试成本最高昂的阶段。从2008年到2017年的10年间,有420次药品的第三期临床试验以“终止、暂停或停药”告终。(另有350次试验以“未指明或其他”为理由叫停了试验。” 在以上试验中,有整整三分之一的“失败”是由于参与者数量或试验完成率过低导致的。超过四分之一(27%)的失败是由于药品功效不足——药效未显著超出安慰剂效应或比较疗法(这个比例比因为不良反应或副作用而失败的比例高出两倍多)。那么,有多少盘子是在服务员的手上摔碎的?答案是,有51次失败由于“商业/战略决策”导致的。(当然,这些数据可能隐藏了大量的模糊定义,所以我只能指出一个大概方向,而不可能给出十分精确的数字。) |

By necessity, pharma embraces, or wraps itself in, failure. It is where we measure the difficulty of intervening in the biological complexity of health or illness, so it is perhaps unsurprising that our intended consequences are continually humbled by the unintended. The word ‘failure’ is both overused and under-challenged in pharma. At first glance, it seems such an obvious concept – “We tried, but didn’t succeed.” But the simple notion of failure sits behind our common understanding of success rates in drug development, and how difficult (and therefore expensive) it is to even get one medicine to market. That ratio is at the core of industry demands to “protect our innovation.” If we launch only 40-50 new medicines per year in the current system, just imagine what might happen if we start to lower the reward, the thinking goes. The word “attrition” is used as if losses are inevitable, massive, and unpredictable. However, if your waiter drops 4 of the 5 plates he is bringing to your table, but is able to load the cost of all 5 onto the bill for the appetizer that does make it, it might be reasonable to ask what incentive there would be to improve his carrying skills. At first glance, the analogy falls down – these dishes have already made it into the waiter’s hands, rather than failing in development. But what if our waiter decided just to leave them there under the kitchen hot lamps, because, well, it just isn’t worth it to bring them to you? (Oh and, by the way, you’re still paying the big check regardless.) On that note, here’s something interesting in the figures from the most expensive phase of drug R&D – discontinuations in late-stage, phase 3 clinical trials. In the 10 years from 2008 to 2017, 420 pharma phase III trials cited “termination, suspension, or withdrawal” (another 350 gave “unspecified or other” as their toe tag for their would-be drugs). Fully one third of the “failures” were for low trial recruitment and completion rates. More than one in 4 (27%) failed for lack of efficacy – the drug worked no better than placebo, or a comparator treatment (that’s more than twice the number that failed for adverse events or side effects). Those ultimately doomed plates that made it to the waiter’s hands? 51 of the terminations were for “Business/Strategic Decision.” (These data can of course hide a great deal of “definition” murk, so I am using them directionally, rather than as numerically accurate.) |

|

很多试验竟然是因为招不到足够的病人导致的,我们不禁好奇为什么会发生这种事。原因有很多,有的是因为外包机构(也就是那些给制药公司干杂活的第三方公司)做了过度承诺,有的是因为试验本身缺乏真正需要满足的医疗需求,有的是因为难以将病人送到试验地点,还有的可能是由于某份研究将试验的对照组置于了不利地位。 (另外,还有一种人们可能意想不到的后果:我们习惯于寻找一种药物的潜在疗效的纯粹“信号”,但同时我们也应该意识到,真正世界的用药并非这样简单——它还必须不能给真实的、活生生的病人造成伤害。) 以上这些数字,代表的并非是失败,而是机会。我们没有理由认为这些药品都是无效的,或是都是不安全的——它们只是没有被批准。 为了检验一种试验性疗法的效果,试验的失败率往往是惊人的。药品的早期研发阶段往往只是为了寻找某种药品是否有效的一个极微小的信号,制药公司仍然需要开展大规模的三期测试,以试验药品的效果是否足够好。我们必须对我们的期望抱小心谨慎的态度。当然,如果我们在三期测试里只搞一些“简单”的研究,将失败率降到0%也不是没有可能。但没有人想要这种试验。 同样,0%的成功率对我们所有人来说也是灾难性的。不过,“飞鱼”菲尔普斯游泳是一把好手,让他玩潜水可能并不在行。同理,一种药品在三期测试中失败了,是否等于说它一定不是一种好药呢?一个问题换另一种问法,会不会得到不同的答案? 在我们这些希望制药行业能够向患者提供更多药品(同时希望新药上市的速度更快、成本更低)的人看来,“商业/战略决策”一项自然就成了一个值得研究的类别。请注意,这个类别跟财务问题无关,跟“因为缺钱而失败”不是一回事。这些药品之所以被制药企业搁置了,是因为企业觉得与它们的营销成本和开发它们的机会成本(比如沉没成本、持续成本等)相比,它的潜在回报太低。如果扩大价值的外延,我们必须承认,在这一类别的药品中,也包含了能够为病人提供价值的药品。 一笔资产不符合公司的战略方向,原因可能有很多——比如公司决定朝着某个特定方向发展,或者公司决定退出某个特定的治疗领域。再或者公司在该领域研制的几种药品都有效果,公司只能决定保留其中希望更大的一个。 无论是以上哪种情形,这些药品都可能是对患者有用的药品。如果一种药品为了给另一种药品让路而不得不被束之高阁,我们惋惜之余,不禁会想:有没有别的办法可以继续研究这种药品?要知道,在制药行业的历史中,很多成功的药品在研发阶段都有过“假失败”的历史。(可能要比那些靠胡蒙瞎猜的“专家”们愿意承认的还要多。) 一种完美的药品“由于商业计划而失败”的原因有很多,比如如果它的赚钱前景不够理想,公司就有可能将它裁掉。比方说,一家公司对一笔资产的预期回报是每年10亿美元。如果预计达不到这个回报率,公司就没有动力推动这个研发项目。不过,在药品上市之前,即便预期收益再乐观,也经常会被现实狠狠地抽一记耳光——反之也是如此,预期中的冷门药热卖的情况也不是没有。所以,光靠推测一种药物一年能不能卖出10亿美元就去给它判死刑,并非明智的做法。这种药品可能是该领域里最好的甚至唯一的药品,但很多这种药品,却因为被错误地认为没有远期价值,而折戟于一场错误的测试。 也可能有人认为,某种药品之所以在三期试验中被拿下了,是因为它的效果不如市面上已经存在的竞品。事实上,光靠三期试验的数据,是很少能够做出这样的结论的——因为这些数据很少与有效的治疗标准做针锋相对的比较。光靠目前的研究,也很难回答这些药品与其他竞品相比的有效性问题。 所以,虽然一种药品因为“商业计划”而被扼杀的原因可能有很多,但我们也有充分理由相信,不同的利益主体,很可能会就此做出不同的决定。两家看似大同小异的公司,很可能会做出完全不同的决策,更不用说预测本身就是个非常主观的行为。哪怕是同一个人,同一个团队,在不同的环境下(或者面临来自高管层的不同压力时),也可能做出不同的决策。 如果一家公司不那么贪心,或者在药品研发组合上采取了不同的配置,那么它可能乐于向市场推出更多的产品。一家公司如果在经济上没有迫切需求,也可能将这个“垃圾填埋场”视为宝库,发掘出更多的“可回收材料”。 彼得·阿迪曾经在播客里采访过音乐制作人里克·鲁宾,鲁宾在谈到他的经历时,曾经说过一句很有意思的话:“哥伦比亚公司有一个政策,他们宁可让这些作品死掉,也不愿意看到别人靠它们成功……” 如果一种药品“由于商业计划”而失败了,我们理应去问,还有谁有权拿到这个药物?毕竟,其他人可能会对它的战略价值给出不同的结论,甚至有可能在它的基础上推出一款成型的药物——它虽然没能满足一开始研发它的那家公司的需求,但却仍然能够满足病人的需求。(财富中文网) 本文作者之一的迈克·雷(Mike Rea)是IDEA Pharma公司的CEO,另一作者埃内达·波洛兹(Eneida Pollozi)是该公司的战略顾问。 译者:朴成奎 |

When so many studies “fail” for their ability to recruit patients, we of course might wonder why. The reasons are legion, from over-promising by hard-tendering contract research organizations (the third-party firms hired to do the major leg work for many pharma companies), to lack of a true unmet medical need, to difficulty getting patients to trial sites, or possibly a study that would put a control group at a disadvantage. (By the way, there’s another unintended consequence: We’re conditioned to look for pure “signals” of a drug’s potential efficacy, but we need to recognize that can be at odds with how prescribing works in the real world – doing no harm to real, live patients). One thing to take away, however, is not the failure, but the opportunity. We’ve no reason to believe that these medicines are ineffective, or unsafe – just unproven. The failure rate associated with an experimental treatment’s efficacy is staggering. There is a consequence of using early phases of R&D just to look for the tiniest signal that a drug might work: Companies are still using massive phase III programs just to find out if their drugs work well enough. We have to be careful what we wish for. It is, of course, possible to have a 0% failure rate for efficacy in phase III, by only conducting “easy” studies. None of us need that. Equally, a 0% success rate would be disastrous for all of us. However, like judging Michael Phelps by his ability to dive, let’s acknowledge that a drug that “fails” a phase III study could equally ask, “Did the study fail a good drug?” That is, could a different question asked of the same drug have yielded a different answer? That then makes the category of “Business/ Strategic Decision” an appealing one , for those of us who wish that the industry would get more medicines to patients (and thereby get them there faster and more cost-effectively). Note that this category is separate from financial reasons, where “failure for lack of money” would sit. No, these are products shelved because the company has decided there’s less value coming back from the drug than the marketing and opportunity cost of developing it (sunk cost and/or ongoing commitments, for example the cost of marketing. While we’re discussing that broader notion of value, this category, let’s be clear, does also include drugs that may provide value to the patient. There may be many reasons an asset doesn’t fit strategically – a decision to move a company portfolio in a certain direction, or out of a particular therapeutic area, for example. It could be that more than one candidate worked, and a choice had to be made as to which would be the one taken forward. In either case, these kinds of drugs could potentially be useful medicines. If shelved to make way for another medicine in the portfolio, we’re left wondering – was there a different way that this medicine could have been studied, or could still be? This history of pharma’s successes includes many medicines that had “false fails” in their development (more, perhaps than any of our prediction-based scientists would like to acknowledge). Among the reasons that a perfectly good medicine might “fail for business plan” is that the company might have a cut-off for a business case that the asset doesn’t clear. Let’s say, for example, that a company won’t progress an asset that can’t be forecast to return $1 billion per year. Unfortunately, even the most optimistic estimates of revenue forecasting in pre-launch suggest it is usually wrong (and wrong equally in both directions). So, that $1 billion figure seems an odd number to rely upon to nix a drug. It may be the best and only one we have, but let’s focus on what matters – many of these medicines have wrongly been estimated to have no forward value: They “failed” a false test. Or, perhaps, the drug is expected to perform less well than a competitor that’s already out there. Well, phase III data are rarely useful enough to draw such a conclusion – because they are rarely head-to-head with the effective standard of care, and registrational studies are unfortunately still not set up to answer questions about such drugs’ comparative effectiveness versus others. So, for all the reasons a drug might “fail for business plan,” there are a host of reasons to believe that a body with different interests might make a different decision. As we know, two similar-looking but different companies might well have taken different decisions, not least because forecasts are remarkably subjective – the team or the individual producing those forecasts might produce a different forecast in a different environment (or with different senior management pressures). A company with lighter appetites, or a different approach to portfolio positioning, may progress more products that happily sit on market together. An organization with less of a financial motive, of course, may regard this landfill site as, instead, being full of recyclable material. There was a fascinating line in the Peter Attia podcast with Rick Rubin, discussing the history Rubin had experienced, in hoping a major might let artists move between stables, for their own sake: ‘Columbia has a policy: they’d rather see these works die than see someone else have success with them…’ If a product fails “for business plan,” it is legitimate to ask the question about who else should have access to that drug, to arrive at a different conclusion about its strategic value, and potentially to launch a medicine that may not have satisfied its original company that worked on it – but which still might meet patients' needs. Mike Rea is the CEO of IDEA Pharma, and Eneida Pollozi is a strategy consultant at the company. |