量少价低:抗生素行业将面临重大危机

|

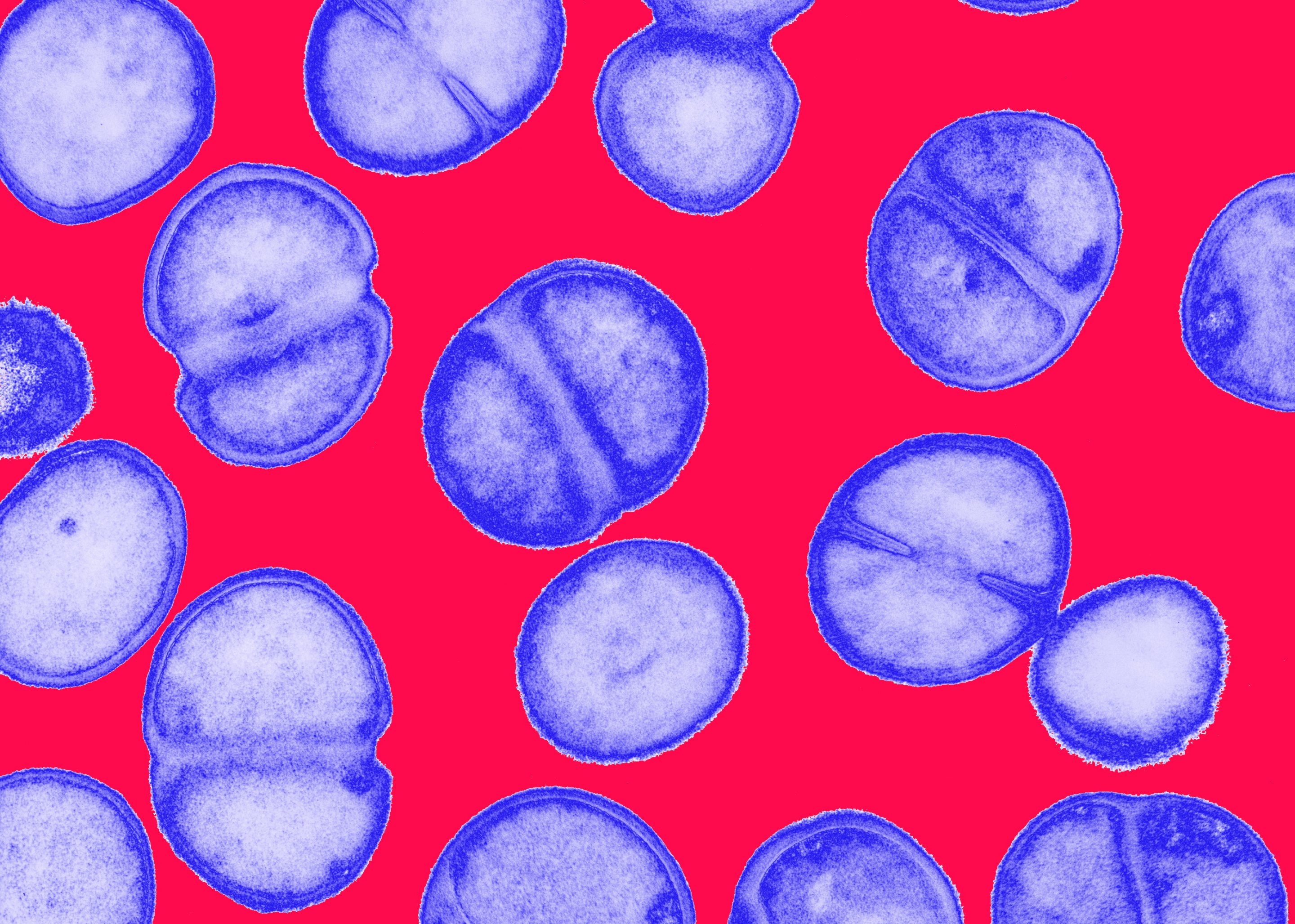

今年6月,一批生物科技行业的代表人物汇聚旧金山。他们此行的目的是竞购制药公司Achaogen的资产,后者于今年4月申请了破产保护。经过一番商讨和争夺,最大的竞购者以1600万美元的价格带走了Achaogen的几乎所有资产。 一家制药公司被迫关门本身未必是异常之事或者有新闻价值,但Achaogen并不是一个典型的生物科技公司破产事件。 2017年7月,Achaogen的市值还在10亿美元以上(Venrock对Achaogen 投资的时间是2004年)。更重要的是,Achaogen已经成功发现并开发出了一种针对严重抗药性感染的抗生素,并且通过了美国食品与药品监督管理局(FDA)的审批。此外,该公司药物是第一种获得美国食品与药品监督管理局突破性疗法认定的抗生素。 与此同时,在美国东海岸,设在波士顿的抗生素厂商Tetraphase在取得了类似成功后也开始陷入困境。和Achaogen一样,Tetraphase开发的针对抗药性细菌感染的抗生素也通过了美国食品与药品监督管理局的审批,这是一项壮举。Tetraphase的市值也曾经接近20亿美元,但现在已经跌至1000万美元以下。 旨在推动抗生素创新的合作组织CARB-X的执行董事凯文·奥特森在今年夏天曾经向生物制药网站发表声明称:“[抗菌剂]公司呈直线下滑状态,需要采取紧急行动来阻止这个行业的崩溃。” 虽然普通大众越发意识到抗菌剂公司的麻烦正在不断增大,但在生物科技领域以外,几乎没有人知道抗生素行业正在面临着另一场商业危机。 为什么像Achaogen和Tetraphase这样“成功”的抗生素公司发现自己在商业领域难以立足呢?归根到底是新抗生素面临的两大问题:量少和价低。 第一个因素是量少,这在一定程度上和新抗生素的管理有关。在知道病人需要针对耐药感染的抗生素前,医生对于开这些新抗生素持有保留态度。此外,和其他许多药物不同,大多数抗生素都需要添加到医院的处方集中,而这需要院方进行三到四轮的审核。结果就是新抗生素在上市的头几年中的销量微乎其微。 第二个因素是价低,其原因是抗生素的报销方式。在感染病人到医院后,医院会拿到一笔钱,被称为诊断相关资金(DRG),其中包括病人在医院接受的所有治疗,包括开给他的抗生素。 要点在于,诊断相关资金中未使用的部分都会称为医院的利润。这就促使医院尽可能地使用平价抗生素。此外,这就意味着当医院选择开非常贵的抗生素时,通过诊断相关资金根本报销不了,而医院必然会出现亏损。 因此,创新抗生素的平均价格远低于其他治疗领域的创新药价格,而且大多数药费都不是通过诊断相关资金支付的。 受此影响,风投资金对新抗生素的兴趣不断减弱。生物科技行业组织Biotechnology Innovation Organization的一项分析显示,2009-2013年为开发创新抗生素投入的风投资金总额约为6亿美元。而在此期间,神经药物开发公司一共筹集了17亿美元风投资金,抗肿瘤药制造商的风投融资额为42亿美元。 我们怎样才能矫正这种动力上的偏差呢?可能方法之一是立法。2018年由民主、共和两党联合提出的DISARM法案建议将抗生素排除在诊断相关资金之外。具体来说,该法案允许美国联邦医保向使用合格抗生素的医院另行支付一笔钱。 民主、共和两党共同推出的另一项法案是REVAMP,其目的是向开发出新型重大抗生素的公司颁发证书,使其获得更长的独占权。随后,另一家公司可以买下这样的证书,以确保自身产品也有更长的独占权。 可以用儿科优先审核证书(针对儿科疾病的证书)来估算抗生素证书的价格;而且有很多儿科优先审核证书的售价都超过了1亿美元。 考虑到这些数字,一本这样的证书实际上是一份现金奖励,从而使抗生素开发公司不受获批头几年销售增长缓慢的影响。这段时期一家公司的支出通常会超过收入,这本证书则可以带来关键的资金支持。 DISARM或REVAMP法案获得通过都有可能极大地促进新抗生素的开发。但不幸的现实是,目前对付耐药性对两党来说都不是很紧迫的任务。市场力量让开发新抗生素变得如此困难,而要出现改变市场力量的希望,就要先改变这种局面。 如果等式的一边是调整市场,那么另一边就是增加新的后备抗生素。美国食品与药品监督管理局的高级官员珍妮特·伍德科克对目前的后备抗生素的描述是“薄弱而且乏力”,这在很大程度上是因为上文谈到的投资者不感兴趣问题。 考虑到生物制药的周期,后备产品薄弱会带来特别大的问题,因为开发新药的时间很容易就会达到甚至超过10年。 美国政府、健康和人类服务部(Department of Health and Human Services)以及CARB-X等行业组织正在资助公司推进新抗生素的开发。CARB-X已经从美国和英国政府以及维康信托基金会、比尔及梅琳达·盖茨基金会等慈善组织手中获得了约5亿美元资金。 这笔资金非常关键,但实际上可能不够多。要明白其中的理由,大家可以考虑一下,美国健康和人类服务部下属的生物医药高级研发局(Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority)为Achaogen提供了近1.5亿美元资金,目的是推动该公司的抗生素完成三期临床实验。就连这种规模的政府资金也不足以让这家公司在商业层面上生存下来。实际情况证明,量少和价低的组合问题极难解决。 为重新打造后备抗生素并应对不断增强的耐药性,公司需要政府和非营利组织提供的资金。但这些资金还不够。我们还必须修正市场,因为首先是市场给抗生素开发带来了如此巨大的挑战。 如果新抗生素仍然以不合理的低价进行报销并且用在非常少的病人身上,开发这些药在商业上仍然无法立足。非营利组织和政府支持这些公司的时间段可能不光是在争取美国食品与药品监督管理局审批的过程中,它还包括获得美国食品与药品监督管理局审批后收入微薄的那几年。 这可能意味着政府要改变以往鼓励药物开发的模式,但实际情况也证明,抗生素独具一格。无法及时解决这个问题就可能影响美国(乃至全世界)为下一轮严重抗药性感染做好准备。(财富中文网) 梅根·布卢伊特是风投公司Venrock的投资人。 鲍勃·柯歇尔是风投公司Venrock的投资人、南加州大学谢弗卫生政策和经济中心高级研究员以及斯坦福大学兼职教授。 鲍比·谢迪是医疗科技公司Renew Health的首席增长官。 译者:Charlie 审校:夏林 |

This June, a group of biotech representatives converged on San Francisco. They had come to bid on the assets of pharmaceutical company Achaogen, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April. When all was said and done, the top bidders walked away with virtually all of the company’s assets for $16 million. A pharmaceutical company having to close its doors, in itself, is not necessarily uncommon or newsworthy. But Achaogen’s was not a typical biotech bankruptcy story. As recently as July 2017, Achaogen had a market capitalization of over $1 billion. (Venrock invested in Achaogen in 2004.) More importantly, Achaogen had succeeded in discovering and developing an FDA-approved antibiotic to treat serious, drug-resistant infections. Furthermore, its drug was the first antibiotic to ever receive breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA. Meanwhile, on the opposite coast, Boston-based antibiotic maker Tetraphase is now also struggling after a similar track record of success. Like Achaogen, Tetraphase has developed an FDA-approved antibiotic for drug-resistant bacterial infections—a herculean feat. It once boasted a market cap of nearly $2 billion but now sits at a market cap of under $10 million. Kevin Outterson, executive director of CARB-X, a partnership dedicated to accelerating innovation in the antibiotic space, issued the following statement to Endpoints News this summer: “[Antimicrobial resistance] companies are in free fall and urgent action is needed to stop the collapse of the sector.” While the general public is increasingly aware of the growing toll of antimicrobial resistance, few outside the biotech community are aware of this other, commercial crisis facing the antibiotic sector. Why are “successful” antibiotics companies like Achaogen and Tetraphase finding themselves in commercially untenable situations? It boils down to two problems facing new antibiotics: low volumes and low price points. The first driver, low volumes, is due in part to stewardship of new antibiotics; doctors are reticent to prescribe a new antibiotic for drug-resistant infections before they know patients need it. In addition, most antibiotics, unlike many other medicines, need to be added to hospital formularies, which can require three or four rounds of review from the hospital. The result can be negligible sales for the first several years after the launch of a new antibiotic. The second factor, low price points, is the result of how antibiotics are reimbursed. When a patient is admitted to a hospital with an infection, the hospital receives a lump sum known as a diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment. This covers all the care the patient receives while admitted, including the antibiotics they are prescribed. Importantly, any money under the DRG amount that the hospital does not spend is profit. This incentivizes hospitals to prescribe inexpensive antibiotics whenever possible. Furthermore, this means that when hospitals choose to prescribe a very expensive antibiotic, there is no way to get it reimbursed through the DRG and they are certain to lose money. As a result, the price points for novel antibiotics are much lower on average than the price points for novel medicines in other therapeutic areas; most medicines are not paid for under a DRG. In response, VC interest in new antibiotics has dwindled. According to an analysis by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a trade group representing the biotech industry, venture funding for companies developing novel antimicrobials totaled around $600 million from 2009 to 2013. During the same time period, companies developing neurology medicines raised a total of $1.7 billion in venture funding, and oncology companies secured $4.2 billion in venture investment. How do we go about fixing this case of misaligned incentives? One possibility is legislation. The bipartisan DISARM Act, put forward in 2018, proposes to remove antibiotics from the DRG. Specifically, it would allow Medicare to offer an add-on payment to hospitals that use a qualifying DISARM antibiotic. A second piece of bipartisan legislation, the REVAMP Act, aims to grant companies that develop crucial new antibiotics vouchers to extend their exclusivity. Another company could then buy that voucher to secure additional exclusivity for its own product. Pediatric priority review vouchers (vouchers for conditions affecting children) can be used to estimate the price points one might achieve for antibiotics vouchers: A number of pediatric vouchers have sold for over $100 million. Given these numbers, a voucher program would, in essence, provide a cash prize to allow the antibiotic developer to weather the slow sales uptake in the early years post-approval. This would provide critical funding during a period when a company’s spending typically exceeds its revenue. Passage of either the DISARM Act or the REVAMP Act could significantly incentivize the development of new antibiotics. But the unfortunate reality is that—at the moment—combating antibiotic resistance is not a high priority for either political party. This needs to change if there is to be any hope of fixing the market forces that make it so challenging to develop new antibiotics. If one side of the equation is fixing the marketplace, the other is bolstering our pipeline of new antibiotics. Senior FDA official Janet Woodcock has described the current antibiotic pipeline as “fragile and weak,” driven in large part by the lack of investor interest described above. A weak pipeline is particularly problematic when one considers typical biopharma timelines: It can easily take 10 years or more to develop a new medicine. Government and philanthropic groups like the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and CARB-X are funding companies to advance the development of new antibiotics. CARB-X has secured some $500 million in funding from the U.S. and U.K. governments and philanthropic organizations such as the Wellcome Trust and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This money is critically important but—in reality—likely not sufficient. To understand why, consider this: Achaogen received nearly $150 million in funding from HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to progress its antibiotic through phase 3 clinical trials. Even this level of government funding was not enough to carry the company to commercial viability. The combination of low volumes and low price points proved insurmountable. In order to rebuild our antibiotic pipeline and defend against mounting antibiotic resistance, companies will need capital from government and nonprofit organizations. But this funding is not enough. We must also fix the marketplace that has made antibiotic development so challenging in the first place. If new antibiotics continue to be reimbursed at disproportionately low price points—and prescribed to a very small number of patients—developing these medicines will remain commercially untenable. Nonprofits and the government will likely need to support companies not only in the process leading up to FDA approval, but also in the years afterward when revenues are meager. This would represent a shift in how the government has historically incentivized drug development, but antibiotics have proven to be in a class of their own. Failure to address this problem in a timely manner would undermine our country’s (and the world’s) preparedness for the next wave of serious, drug-resistant infections. Megan Blewett is an investor at the venture capital firm Venrock. Bob Kocher is an investor at Venrock, a senior fellow at the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center, and an adjunct professor at Stanford University. Bobby Shady is the chief growth officer at Renew Health. |