最近的事态似乎显示,监管机构对大型科技公司的清算指日可待。

大型科技公司的力量已经变得无处不在,不容忽视——它们的主导地位不仅体现在股票指数、劳动力市场,也体现在公共话语的监督(或缺乏监督)上,而这些仅仅是其影响力的一小部分。因此,政治剧本似乎正处于一个转折点也就不足为奇了;监管机构现在配备了许多公开抨击科技行业的官员,并且正在加速追猎科技巨头。众所周知,Facebook和谷歌(Google)业已成为反垄断诉讼的目标。

然而,预测大科技公司的报应,或许是一场毫无胜算的赌局。从企业权力到监管重拳的路径既不是线性的,也不是主要与经济有关。今天的辩论往往忽视了“民愤”的催化作用。在过去,这种愤怒的存在毫无差池地凝聚了政治意愿,并促使监管部门强势回应,而它的缺失则减缓或阻止了这种反应。

要想了解为什么“民愤”的政治经济学很可能将决定大型科技公司的监管命运,我们不妨先简要回顾一下美国的监管史。

艾达•塔贝尔的遗产

《谢尔曼法案》(Sherman Act)和1911年肢解标准石油公司(Standard Oil)的事件,如今经常被用来彰显监管风险和权力。然而,一个更有趣的问题是,为什么早在1890年就通过的《谢尔曼法案》被搁置了近20年之久,即使在这段漫长的日子里,政治家们眼睁睁地看着标准石油公司越来越肆无忌惮地滥用其市场权力。是什么改变了这一切?

迫使美国总统泰迪•罗斯福出手的,并不是诸如市场份额见顶或油价高企这类经济指标,而是艾达•塔贝尔,一位在新兴的“扒粪”新闻领域迅速崛起的明星记者。在私人恩怨的驱动下,她开始义无反顾地揭露洛克菲勒帝国的阴暗面。她在1904年出版的畅销书《标准石油公司史》(History of the Standard Oil Company)经《麦克卢尔杂志》(McClure’s Magazine)连载,产生了巨大的影响,并成功地激起了公众反对洛克菲勒家族及其垄断地位的舆论。在成长过程中,塔贝尔目睹了标准石油公司是如何强迫她父亲卖掉其石油生意的——在他拒绝后,他们家不得不抵押了他们的房子。

因此,美国反垄断行动的诞生充分体现了持久的政治经济动态:标准石油公司拥有巨大的政治影响力,多年来始终避免遭受监管行动。然而,迅速高涨的民愤足以凝聚政治意愿,促使监管机构将这部反垄断法律应用到了标准石油公司的身上。

如果你把塔贝尔的胜利视为一个特殊的历史案例,那就错了。恰恰相反,民愤的力量——令人惊讶的是,它往往以文学作为发泄的载体——在20世纪一次又一次地上演。

以美国食品与药品管理局(Food and Drug Administration)的横空出世为例。在《标准石油公司史》面世后不久,与塔贝尔同时代的作家厄普顿•辛克莱出版了《丛林》(The Jungle)一书。尽管它是一部小说,但《丛林》成功地激起了大众对位于芝加哥的肉制品加工厂恶劣生产环境的强烈不满——时至今日,书中描写的细节读起来仍然令人作呕。辛克莱的故事最初发表于1905年,公众的激烈反应促使罗斯福总统签署了《纯净食品和药物法案》(Pure Food and Drug Act)。1906年,这项法案在参议院以63票对4票的压倒性多数票数获得通过,并建立起了现在的美国食品与药品管理局。

还有许多其他例子表明,民愤一直在推动监管行动:1907年的金融恐慌帮助创建了美联储(Federal Reserve);雷切尔•卡森的名著《寂静的春天》(Silent Spring)对另一位共和党总统理查德•尼克松产生了很大影响,最终促使他创建了美国环境保护局(Environmental Protection Agency);2008年的金融大危机(Great Financial Crisis)催生了美国消费者金融保护局(Consumer Financial Protection Bureau),等等。

如果没有民愤,监管机构只能曲折前行

尽管这些历史案例划出了一道道民愤激起监管冲击的直线,但美国监管史上一些最大的反垄断案件确实蜿蜒了数十年之久——你肯定回想起针对美国电话电报公司(AT&T)、IBM,以及后来针对微软(Microsoft)的反垄断案件。事实上,在这些案件中,民愤(或者缺乏民愤)也在决定上述公司的监管命运方面发挥了关键作用。

是的,美国电话电报公司在1982年被分拆了。但它与反垄断监管机构的冲突早在1913年就开始了。多年来,这家公司时而被视为一家好的垄断企业,时而成为一家获得国家认可的垄断企业(忆往昔,你必须向“贝尔大妈”租用电话,但不能拥有它)。历经70年蜿蜒曲折的监管追击,美国电话电报公司最终败诉,并在1982年1月8日同意分拆。

相比之下,在1982年的同一天,监管机构放弃了对IBM长达30年的追猎行动。尽管它避免了被肢解的命运,但累加起来,这些监管战役对IBM的影响甚至大于对美国电话电报公司的影响。IBM被迫将硬件和软件业务分开,这成功地为新的软件巨头开辟了空间,使IBM在战略上处于劣势。

对“贝尔大妈”和“蓝色巨人”的监管要求,并没有民愤作为支撑点。这两家公司没有招致众怒,也许是因为昂贵的长途电话和笨重的电脑没有激发起人们的情感,也许是因为它们的故事中没有塔贝尔或辛克莱那样的人物。这并不妨碍监管部门采取行动,但这种行动只是源自技术官僚的担忧,并逐渐演变为一场冗长的监管舞蹈,最终也产生了远比标准石油公司的命运好得多的结果。

后来,微软挺进了IBM收缩战线所开辟的新空间。是的,就民愤和监管行动的关联而言,这家软件巨头仍然是一个有趣的案例,因为其中包括了一些民愤因素。许多人很容易忘记,在20世纪90年代末,也就是对微软的监管审查达到顶峰的时候,这家企业和比尔•盖茨是多么令人厌恶:对网景(Netscape)的欺凌、捆绑销售软件,以及盖茨在美国国会听证会上被广泛抨击的表现,都激起了民众的不满情绪,甚至让许多人极度憎恶。

大多数人如今都忘记了,法官在2000年裁定微软应该分拆——这是一个与近年来的大众情绪相呼应的快速判决。然而,这种愤怒并没有在政府更迭和上诉中持续下去。2001年,美国司法部(Justice Department)表示不再寻求分拆微软,并同意达成和解。

科技巨头的监管命运更像标准石油公司还是IBM?

尽管以历史作为参照时,我们始终应该保持谨慎,但民众的强烈反应(或缺乏反应)与强烈的监管反应(或缺乏反应)之间的关联仍然令人信服。在某种程度上,如果我们把反垄断监管看作是一个由技术专家操刀的经济分析领域,那就是一件非常令人惊讶的事情。而如果我们把它看作是政治家对激励的反应,比如当企业权力的影响力被民愤对选情的威胁压倒时,那就不那么令人惊讶了。

那么,今天是否存在足以引发政治反应的民愤呢?还没有那么大。民众的不满情绪有两种我们需要同时关注的类型:一个是经济上的,另一个则发生在政治层面。

经济上的不满情绪通常归结为消费者对定价不当(价格过高)或质量低劣(产品有害)的反应。但科技巨头正在免费提供高价值产品——至少在大多数消费者看来是这样。广大消费者不会给自己的个人数据、隐私,以及自己愿意给予,而平台非常渴望获得的关注度定价。它仍然是一种易货贸易,而不是一种透明的经济交易。因此,在科技产品越来越强大的背景下,经济因素引发的民愤不太可能增长。

对科技公司社会影响的政治怨恨,似乎会成为一股更强大的力量。这尤其适用于对平台控制言论的关切。政治右翼对“去平台化”趋势极度不满。而政治左翼的反对意见主要集中在平台放大错误信息和分裂性言论方面。今天所缺乏的是一种足以凝聚政治共识的“同仇敌忾”——在如今这样一个高度党派化和高度分裂的政治环境中,这显然是一个极高的门槛。

有鉴于此,大型科技公司被监管机构肢解的可能性看起来并不大。但如果这些科技巨头不会重蹈标准石油公司的覆辙,它们是否会踏上IBM的老路?现在看来,我们更有可能见证一场漫长而曲折的监管反击战。这场游戏更有可能在拥有监管权力的官僚机构中进行。现在,监管机构正在就反垄断的含义展开一场法律辩论,“新布兰代斯”学派主张对竞争进行更广泛的定义,而不仅仅是狭隘地关注消费者的成本和收益。

这很可能是一条漫长而曲折,充斥着无数法律和政治障碍的道路,其中包括企业自身的游说影响力。尽管对于大型科技公司的企业战略来说,这种潜在的监管反击仍然是一项重大挑战,但它看起来更像是一场长期游戏,而不是那种足以在短期内瓦解科技巨头权力的“大爆炸”。让我们期待变革,而不是革命。是的,科技巨头还将继续存在下去。(财富中文网)

本文作者菲利普•卡尔森-斯莱扎克是波士顿咨询公司(BCG)纽约办事处的董事总经理、合伙人,也是该集团的全球首席经济学家。保罗•斯沃茨是波士顿咨询公司亨德森研究所(BCG Henderson Institute)的董事、高级经济学家,常驻纽约办事处。

译者:任文科

最近的事态似乎显示,监管机构对大型科技公司的清算指日可待。

大型科技公司的力量已经变得无处不在,不容忽视——它们的主导地位不仅体现在股票指数、劳动力市场,也体现在公共话语的监督(或缺乏监督)上,而这些仅仅是其影响力的一小部分。因此,政治剧本似乎正处于一个转折点也就不足为奇了;监管机构现在配备了许多公开抨击科技行业的官员,并且正在加速追猎科技巨头。众所周知,Facebook和谷歌(Google)业已成为反垄断诉讼的目标。

然而,预测大科技公司的报应,或许是一场毫无胜算的赌局。从企业权力到监管重拳的路径既不是线性的,也不是主要与经济有关。今天的辩论往往忽视了“民愤”的催化作用。在过去,这种愤怒的存在毫无差池地凝聚了政治意愿,并促使监管部门强势回应,而它的缺失则减缓或阻止了这种反应。

要想了解为什么“民愤”的政治经济学很可能将决定大型科技公司的监管命运,我们不妨先简要回顾一下美国的监管史。

艾达•塔贝尔的遗产

《谢尔曼法案》(Sherman Act)和1911年肢解标准石油公司(Standard Oil)的事件,如今经常被用来彰显监管风险和权力。然而,一个更有趣的问题是,为什么早在1890年就通过的《谢尔曼法案》被搁置了近20年之久,即使在这段漫长的日子里,政治家们眼睁睁地看着标准石油公司越来越肆无忌惮地滥用其市场权力。是什么改变了这一切?

迫使美国总统泰迪•罗斯福出手的,并不是诸如市场份额见顶或油价高企这类经济指标,而是艾达•塔贝尔,一位在新兴的“扒粪”新闻领域迅速崛起的明星记者。在私人恩怨的驱动下,她开始义无反顾地揭露洛克菲勒帝国的阴暗面。她在1904年出版的畅销书《标准石油公司史》(History of the Standard Oil Company)经《麦克卢尔杂志》(McClure’s Magazine)连载,产生了巨大的影响,并成功地激起了公众反对洛克菲勒家族及其垄断地位的舆论。在成长过程中,塔贝尔目睹了标准石油公司是如何强迫她父亲卖掉其石油生意的——在他拒绝后,他们家不得不抵押了他们的房子。

因此,美国反垄断行动的诞生充分体现了持久的政治经济动态:标准石油公司拥有巨大的政治影响力,多年来始终避免遭受监管行动。然而,迅速高涨的民愤足以凝聚政治意愿,促使监管机构将这部反垄断法律应用到了标准石油公司的身上。

如果你把塔贝尔的胜利视为一个特殊的历史案例,那就错了。恰恰相反,民愤的力量——令人惊讶的是,它往往以文学作为发泄的载体——在20世纪一次又一次地上演。

以美国食品与药品管理局(Food and Drug Administration)的横空出世为例。在《标准石油公司史》面世后不久,与塔贝尔同时代的作家厄普顿•辛克莱出版了《丛林》(The Jungle)一书。尽管它是一部小说,但《丛林》成功地激起了大众对位于芝加哥的肉制品加工厂恶劣生产环境的强烈不满——时至今日,书中描写的细节读起来仍然令人作呕。辛克莱的故事最初发表于1905年,公众的激烈反应促使罗斯福总统签署了《纯净食品和药物法案》(Pure Food and Drug Act)。1906年,这项法案在参议院以63票对4票的压倒性多数票数获得通过,并建立起了现在的美国食品与药品管理局。

还有许多其他例子表明,民愤一直在推动监管行动:1907年的金融恐慌帮助创建了美联储(Federal Reserve);雷切尔•卡森的名著《寂静的春天》(Silent Spring)对另一位共和党总统理查德•尼克松产生了很大影响,最终促使他创建了美国环境保护局(Environmental Protection Agency);2008年的金融大危机(Great Financial Crisis)催生了美国消费者金融保护局(Consumer Financial Protection Bureau),等等。

如果没有民愤,监管机构只能曲折前行

尽管这些历史案例划出了一道道民愤激起监管冲击的直线,但美国监管史上一些最大的反垄断案件确实蜿蜒了数十年之久——你肯定回想起针对美国电话电报公司(AT&T)、IBM,以及后来针对微软(Microsoft)的反垄断案件。事实上,在这些案件中,民愤(或者缺乏民愤)也在决定上述公司的监管命运方面发挥了关键作用。

是的,美国电话电报公司在1982年被分拆了。但它与反垄断监管机构的冲突早在1913年就开始了。多年来,这家公司时而被视为一家好的垄断企业,时而成为一家获得国家认可的垄断企业(忆往昔,你必须向“贝尔大妈”租用电话,但不能拥有它)。历经70年蜿蜒曲折的监管追击,美国电话电报公司最终败诉,并在1982年1月8日同意分拆。

相比之下,在1982年的同一天,监管机构放弃了对IBM长达30年的追猎行动。尽管它避免了被肢解的命运,但累加起来,这些监管战役对IBM的影响甚至大于对美国电话电报公司的影响。IBM被迫将硬件和软件业务分开,这成功地为新的软件巨头开辟了空间,使IBM在战略上处于劣势。

对“贝尔大妈”和“蓝色巨人”的监管要求,并没有民愤作为支撑点。这两家公司没有招致众怒,也许是因为昂贵的长途电话和笨重的电脑没有激发起人们的情感,也许是因为它们的故事中没有塔贝尔或辛克莱那样的人物。这并不妨碍监管部门采取行动,但这种行动只是源自技术官僚的担忧,并逐渐演变为一场冗长的监管舞蹈,最终也产生了远比标准石油公司的命运好得多的结果。

后来,微软挺进了IBM收缩战线所开辟的新空间。是的,就民愤和监管行动的关联而言,这家软件巨头仍然是一个有趣的案例,因为其中包括了一些民愤因素。许多人很容易忘记,在20世纪90年代末,也就是对微软的监管审查达到顶峰的时候,这家企业和比尔•盖茨是多么令人厌恶:对网景(Netscape)的欺凌、捆绑销售软件,以及盖茨在美国国会听证会上被广泛抨击的表现,都激起了民众的不满情绪,甚至让许多人极度憎恶。

大多数人如今都忘记了,法官在2000年裁定微软应该分拆——这是一个与近年来的大众情绪相呼应的快速判决。然而,这种愤怒并没有在政府更迭和上诉中持续下去。2001年,美国司法部(Justice Department)表示不再寻求分拆微软,并同意达成和解。

科技巨头的监管命运更像标准石油公司还是IBM?

尽管以历史作为参照时,我们始终应该保持谨慎,但民众的强烈反应(或缺乏反应)与强烈的监管反应(或缺乏反应)之间的关联仍然令人信服。在某种程度上,如果我们把反垄断监管看作是一个由技术专家操刀的经济分析领域,那就是一件非常令人惊讶的事情。而如果我们把它看作是政治家对激励的反应,比如当企业权力的影响力被民愤对选情的威胁压倒时,那就不那么令人惊讶了。

那么,今天是否存在足以引发政治反应的民愤呢?还没有那么大。民众的不满情绪有两种我们需要同时关注的类型:一个是经济上的,另一个则发生在政治层面。

经济上的不满情绪通常归结为消费者对定价不当(价格过高)或质量低劣(产品有害)的反应。但科技巨头正在免费提供高价值产品——至少在大多数消费者看来是这样。广大消费者不会给自己的个人数据、隐私,以及自己愿意给予,而平台非常渴望获得的关注度定价。它仍然是一种易货贸易,而不是一种透明的经济交易。因此,在科技产品越来越强大的背景下,经济因素引发的民愤不太可能增长。

对科技公司社会影响的政治怨恨,似乎会成为一股更强大的力量。这尤其适用于对平台控制言论的关切。政治右翼对“去平台化”趋势极度不满。而政治左翼的反对意见主要集中在平台放大错误信息和分裂性言论方面。今天所缺乏的是一种足以凝聚政治共识的“同仇敌忾”——在如今这样一个高度党派化和高度分裂的政治环境中,这显然是一个极高的门槛。

有鉴于此,大型科技公司被监管机构肢解的可能性看起来并不大。但如果这些科技巨头不会重蹈标准石油公司的覆辙,它们是否会踏上IBM的老路?现在看来,我们更有可能见证一场漫长而曲折的监管反击战。这场游戏更有可能在拥有监管权力的官僚机构中进行。现在,监管机构正在就反垄断的含义展开一场法律辩论,“新布兰代斯”学派主张对竞争进行更广泛的定义,而不仅仅是狭隘地关注消费者的成本和收益。

这很可能是一条漫长而曲折,充斥着无数法律和政治障碍的道路,其中包括企业自身的游说影响力。尽管对于大型科技公司的企业战略来说,这种潜在的监管反击仍然是一项重大挑战,但它看起来更像是一场长期游戏,而不是那种足以在短期内瓦解科技巨头权力的“大爆炸”。让我们期待变革,而不是革命。是的,科技巨头还将继续存在下去。(财富中文网)

本文作者菲利普•卡尔森-斯莱扎克是波士顿咨询公司(BCG)纽约办事处的董事总经理、合伙人,也是该集团的全球首席经济学家。保罗•斯沃茨是波士顿咨询公司亨德森研究所(BCG Henderson Institute)的董事、高级经济学家,常驻纽约办事处。

译者:任文科

Recent developments might suggest that Big Tech is nearing its regulatory reckoning.

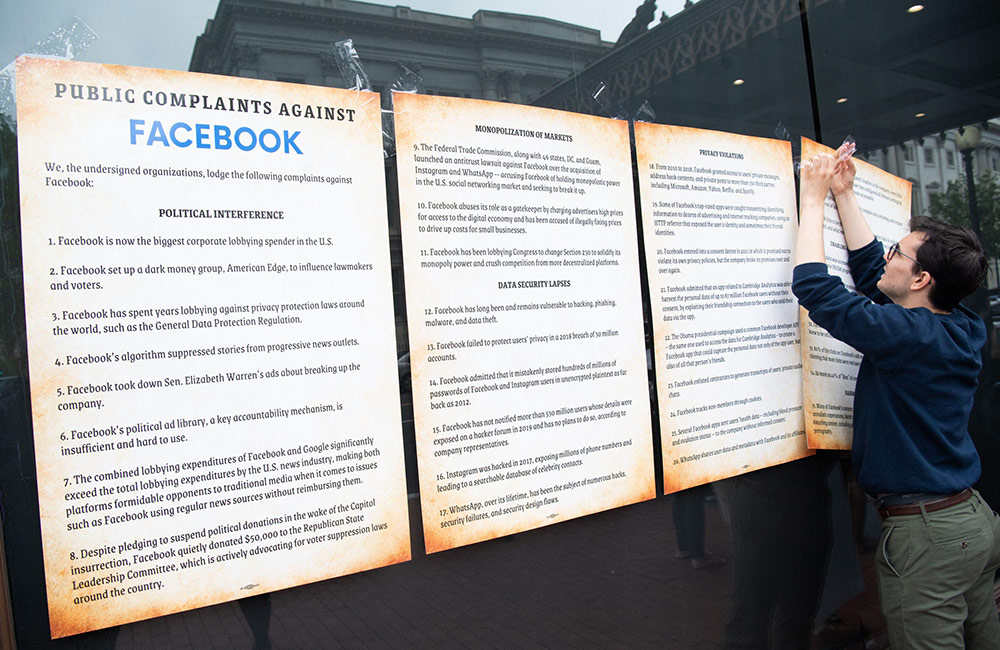

The power of the biggest tech companies has grown too ubiquitous to ignore—their dominance can be felt in the stock indexes, in segments of the labor market, and in the oversight (or lack thereof) of public discourse, to name just a few areas of influence. Little surprise, then, that the political script appears to be at a turning point: Regulatory agencies, now staffed with vocal critics of the industry, are accelerating the pursuit, with Facebook and Google squarely in the crosshairs of antitrust litigation.

Yet predicting Big Tech’s comeuppance could be a losing bet. The path from corporate power to regulatory backlash is neither linear nor predominantly about economics. What’s overlooked in today’s debate is the catalyzing power of popular outrage. The presence of such anger has reliably aligned political will and driven regulatory pushback in the past—and its absence has slowed or prevented such pushback.

To see why the political economy of outrage will likely shape Big Tech’s regulatory fate, a brief tour of U.S. history is a good starting point.

The legacy of Ida Tarbell

The Sherman Act and the dismemberment of Standard Oil in 1911 are often invoked today to highlight regulatory risk and power. However, a more interesting question is why the Sherman Act, passed in 1890, sat idle for nearly 20 years, even as politicians watched Standard Oil’s growing abuse of its market power. What changed?

What forced Teddy Roosevelt’s hand wasn’t economic benchmarks such as peaking market share or high prices. It was Ida Tarbell, a star of the emerging field of muckraker journalism, who was on a mission of personal revenge to expose the Rockefeller empire. Her History of the Standard Oil Company (1904) was a bestseller, serialized in McClure’s Magazine to great effect, and successfully galvanized public opinion against the Rockefellers and their monopoly. Growing up, Tarbell had witnessed Standard Oil bullying her father to sell his oil business—when he refused, the family had to mortgage their home.

As such, the birth of U.S. antitrust action captures enduring political-economy dynamics: Standard Oil had enormous political clout and averted regulatory action for years. Yet, a groundswell of popular anger was sufficient to align political incentives to apply the law to Standard Oil.

It would be a mistake to see Tarbell’s victory as a case of idiosyncratic history. On the contrary, the force of public outrage—surprisingly often channeled via the vehicle of literature—plays out again and again in the 20th century.

Consider the emergence of the Food and Drug Administration, for example. Upton Sinclair, a contemporary of Tarbell’s, published The Jungle a little after Tarbell’s History. Despite being a work of fiction, The Jungle spawned massive popular backlash against the disgusting conditions in the meat processing plants of Chicago—the reading remains revolting to this day. The public reaction to Sinclair’s story, initially published in 1905, pushed President Roosevelt to sign the Pure Food and Drug Act, which passed by an overwhelming bipartisan majority of 63 to 4 in the Senate in 1906 and founded what is now the FDA.

There are many other examples of popular resentment driving regulatory action: The financial Panic of 1907 helped create the Federal Reserve; Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring contributed to the swaying of another Republican President, Richard Nixon, to create the Environmental Protection Agency; the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 led to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—and so on.

Without outrage, regulators meander

While the historical examples above draw straight lines from anger to regulatory shock, it is true that some of the biggest antitrust cases in U.S. regulatory history meandered for decades—antitrust cases against AT&T, IBM, and later Microsoft come to mind. Here, too, popular backlash—or the lack of it—played a critical role in shaping their regulatory fates.

Yes, AT&T was broken up—in 1982. But its conflict with antitrust regulators had begun all the way back in 1913. Over the years, the company bounced around from being viewed as a good monopoly to being a state-sanctioned monopoly (recall you had to rent your phone from Ma Bell—but couldn’t own it). After a meandering 70-year regulatory pursuit, AT&T lost its case and agreed to break up on Jan. 8, 1982.

By contrast, on that same day in 1982, a 30-year–long regulatory pursuit of IBM was dropped. Yet despite avoiding a breakup, the cumulative impact on IBM was arguably more significant than that on AT&T. IBM had been pushed into unbundling hardware and software, which successfully opened space for new software behemoths—leaving IBM strategically on the back foot.

Popular anger did not underpin the regulatory pursuits of Ma Bell and Big Blue. They did not inspire indignation, perhaps because expensive long-distance calls and clunky computers did not spark emotion—or perhaps because their stories lacked their Tarbell or Sinclair. That did not prevent regulatory action, but that action played out on the battlefield of technocratic concern, which translated into a long-winded regulatory dance and yielded outcomes far preferable to Standard Oil’s fate.

Microsoft, which moved into the space that IBM’s curtailment had opened, remains an interesting case in the context of outrage and regulation. For there was—some—outrage. It’s easy to forget how loathed in some quarters the firm and Bill Gates were in the late 1990s, just around the time when regulatory scrutiny peaked: the bullying of Netscape, the bundling of software, Gates’ widely panned deposition performance in testimony before Congress, all drove popular dislike if not quite mass resentment.

What remains mostly forgotten today is that the judge ruled, in 2000, that Microsoft should break up—delivering a fast judgment aligned with popular sentiment of recent years. Yet the outrage didn’t sustain itself through political transition and appeal. In 2001 the Justice Department said it was no longer seeking a breakup and agreed to a settlement.

Is Big Tech more like Standard Oil, or IBM?

While history should always be used with care, the correlation between popular backlash (or lack thereof) and sharp regulatory backlash (or lack thereof) remains compelling. In some ways, this is more surprising if we think of antitrust regulation as a field of technocratic economic analysis, and less surprising if we think of it as politicians responding to incentives—such as when the influence of corporate power is outweighed by the electoral threat of outrage.

So, is there outrage today that can drive political backlash? Not so much. There are two types of popular resentment—economic and political—and we need to look at both.

Economic resentment typically boils down to consumers’ reaction to abusive pricing (prices are too high) or low quality (the product is hazardous). But Big Tech is providing high-value products for free—at least in the eyes of most consumers, who do not put a price on their personal data, privacy, and on the attention they willingly give and that platforms crave so much. It remains a barter trade, not a transparent economic transaction, and so economic outrage is unlikely to grow against a backdrop of ever more potent tech offerings.

Political resentment about tech firms’ societal impact looks like it could become a stronger force. This applies in particular to concern about the control of platforms of speech. The political right is infuriated by deplatforming. On the left, opposition centers on the platforms’ amplification of misinformation and divisive speech. What’s lacking today is unifying outrage that aligns political momentum behind a potent argument—an exceedingly high bar in a highly partisan and tightly divided polity.

All this makes a bet on a regulatory dismemberment of Big Tech firms look like long odds. But if Big Tech is not headed the way of Standard Oil, might it be headed the way of IBM? The long and meandering path of regulatory pushback looks much more likely today. Here the game is more likely to be played in bureaucracies of regulatory power. Today’s regulators are in the midst of a legal debate about the meaning of antitrust, with the “New Brandeis” school arguing for a broader definition of competition, not just a narrow focus on costs and benefits to consumers.

This path is likely to be long and winding, strewn with legal and political hurdles, including the lobbying clout of the firms themselves. While this potential pushback remains a significant challenge for Big Tech’s corporate strategy, it looks more like the long game, not the big bang that would dismantle their power in the short run. Expect evolution, not revolution: Big Tech is here to stay.

Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak is a managing director and partner in BCG’s New York office and global chief economist of BCG. Paul Swartz is a director and senior economist at the BCG Henderson Institute, based in BCG’s New York office.