在痴迷棒球的日本,两大职业棒球联盟之一的太平洋联盟(Pacific Baseball League)于今年8月宣布了一项特别推广活动,其中涉及一系列新的球队吉祥物。这些吉祥物包括12位以日本标志性动漫风格绘制的女性角色。

采用动漫角色进行营销推广在日本十分普遍。原创和经过授权的动漫角色被用于宣传产品、商品、服务和各类活动,其中包括2021年东京奥运会(2021 Tokyo Olympics)。

然而,日本棒球联盟所采用的角色有所不同,因为它们在某种程度上是真实的人。

每个角色都是“虚拟主播”经纪公司Hololive旗下的日语主播,虚拟主播是真实的表演者或“达人”在网络上的虚拟形象。隶属于日本公司Cover Corp的Hololive规模位居行业前列,旗下的57名虚拟主播的订阅用户总量高达4300万。除此之外,现在有成千上万的虚拟主播已经将触角伸向中国、韩国、印度尼西亚、美国等市场。

虚拟主播最初被视为日本数字文化中的奇葩,但在过去一年里,它在全球各地越来越受欢迎。新冠肺炎疫情期间,居家隔离的人们普遍在网上寻找娱乐,数百万人选择观看各类直播活动——包括虚拟主播亚文化。

YouTube的官方数据显示,2020年10月,虚拟主播主页每月的播放量达到15亿次。“虽然各种流媒体趋势来来去去,但虚拟主播内容在过去一年一直保持着相当可观的播放量。”流媒体分析公司Stream Hatchet的首席执行官爱德华·蒙特塞拉特指出。

其中最受欢迎的虚拟主播之一是来自日本的Usada Pekora,她之所以走红,是因为她会玩经典的日本角色扮演游戏,常常在《我的世界》(Minecraft)中恶搞其他的虚拟主播,还与印度尼西亚的一位虚拟主播建立了深厚的友谊,尽管双方都不会流利地说对方的语言。根据Stream Hatchet的数据,Pekora是2021年第二季度播放量第三高的女主播。

深厚且忠诚的粉丝基础促使这些达人成为数字明星,尽管——或者可能是因为——他们是以相对匿名的方式藏在虚拟形象背后表演。粉丝们都非常乐意帮助虚拟主播塑造“角色形象”,无论是通过提供翻译服务来开拓新市场,还是打赏支持。

根据Playboard的数据,在从粉丝获得“Superchat”打赏最多的20个YouTube频道中,有17个是虚拟主播。

“最近虚拟主播内容的激增对全球流媒体社区来说并不新鲜,毕竟它在亚洲各大流媒体网站上很受欢迎,在Twitch等西方平台上的播放量也在持续走高。”蒙特塞拉特补充道。

同样引人瞩目的是,一种新型的广告公司正在毫不犹豫地利用这波热潮谋利。

虚拟主播究竟是什么?

从某种意义上说,虚拟主播与常见的主播没有什么不同。这些表演者会玩电子游戏、录制各种反应视频、直播日常活动,并与粉丝交流互动,就像YouTube、Twitch、中国的哔哩哔哩等平台上的其他主播一样。

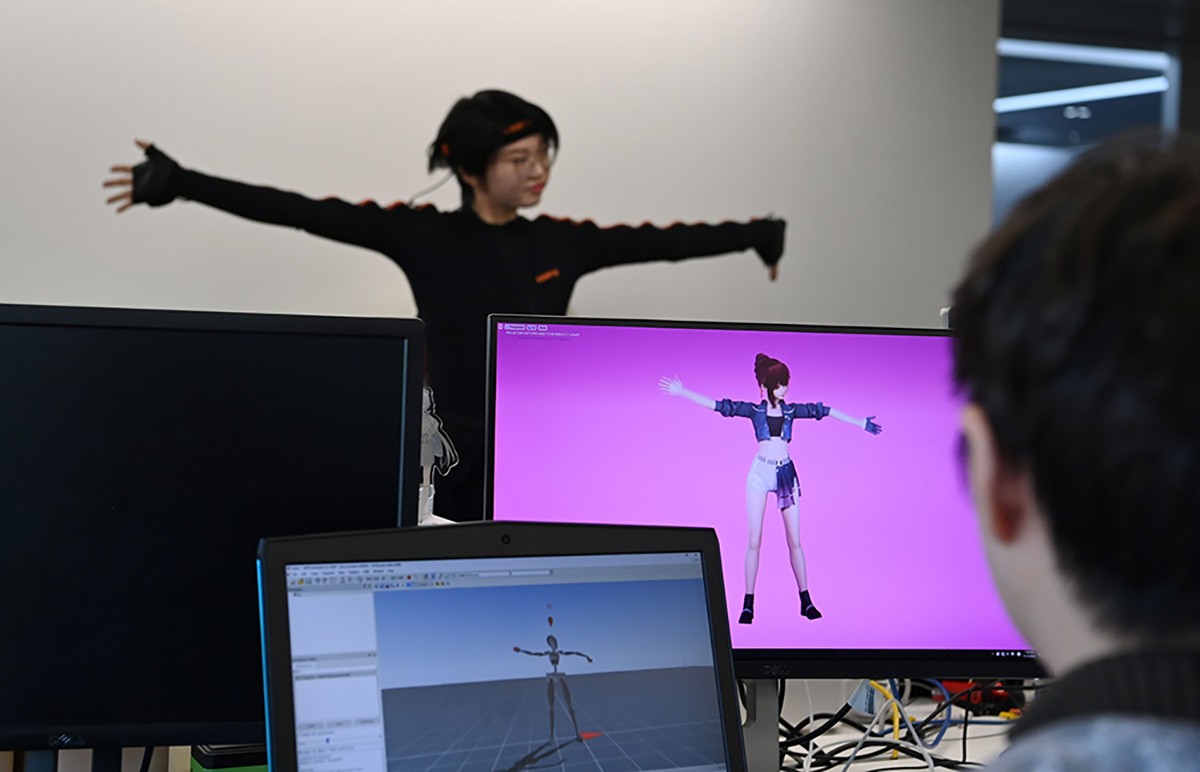

然而,普通主播可能会以自己的名义发布内容,并在镜头前展示自己的真容,而虚拟主播则是藏在虚拟形象背后进行流媒体直播。借助面部识别和动作捕捉技术,虚拟形象会模仿表演者的表情和动作。虚拟主播还经常用假名表演,在观众和实际表演者之间多增加一层屏障。虚拟主播不一定是匿名的——其真实身份有可能被“人肉”出来——但是主播及其粉丝不鼓励讨论虚拟形象背后的人。

虽然虚拟主播早在21世纪10年代初便出现在YouTube上,但直到Kizuna AI出现,并没有虚拟主播真正走红。Kizuna背后的日本声优春日望现年26岁,在“现实世界”中也颇受欢迎。她主持过电视节目,曾经登上杂志封面,甚至担任过日本国家旅游局(Japan’s National Tourism Organization)的代言人。

廉价的面部识别和运动跟踪软件的发展,催生出了大量独立的虚拟主播。但在许多人看来,是Kizuna AI促使这一数字现象变成一门大生意的;几家专门为虚拟主播提供服务的经纪公司没有多久便应运而生,其中包括Cover Corp的Hololive和Anycolor的Nijisanji。

经纪公司为虚拟主播提供基础设施,在后者与Twitch、YouTube等平台打交道时提供技术和法律上的支持;它们还与其他公司签订营销推广协议,比如Hololive对日清(Nissin)的Curry Meshi杯面的宣传推广。

国际吸引力

2020年10月,Hololive推出了第一批主要讲英语的虚拟主播。这些主播的订阅用户数量增长惊人,短短几周便迅速超过了日语主播。其他机构随即跟风:VShojo总部位于旧金山,由Twitch创始团队的一名成员创立,2020年11月面世时便主打一大批英语虚拟主播。其竞争对手Nijisanji也于今年5月上线了自己的英语虚拟主播。

在此之前,全球各地对虚拟直播的兴趣日渐浓厚。日本的经纪机构早就已经开始探索国际扩张,在中国、韩国和印度尼西亚等国招兵买马。与此同时,日语虚拟主播经过译制的内容开始在4Chan、Reddit等海外平台上传播开来。日本的双语主播也开始更多地与国际观众展开互动。

今年早些时候,英语虚拟主播——鲨鱼女孩Gawr Gura——超过了Kizuna AI,成为全球订阅人数最多的虚拟主播。

与此同时,各家经纪机构继续在西方市场开疆辟土:Hololive和Nijisanji均在2021年推出了第二代英语虚拟主播。

走红后的麻烦

虚拟主播——或者更准确地说,虚拟形象背后的表演者——面临着许多与传统主播一样的问题,从在线骚扰和平台运营商的专横决定,到侵犯版权和倦怠。

有的虚拟主播甚至触犯政治红线。

此外,经纪公司可能永久拥有特定虚拟形象或其作品的版权,哪怕最初推广该形象的表演者不再为之效力了(或者,用一家机构的委婉说法,“毕业了”)。与机构不欢而散的表演者会发现他们的视频内容最终被隐匿起来,乃至完全删除。

但是,机构仍然要考虑粉丝的期望和感受。例如,机构之前让Kizuna AI出现在由多个配音演员负责的多个频道,此举引发了粉丝的强烈反对,他们要求用回原配音演员,以消除她要被淘汰的传言。

虚拟主播的未来

尽管近期出现了令人惊艳的增长,但虚拟主播——甚至是虚拟形象这一大概念——并没有引起大多数西方观众的注意,他们更热衷于使用Snapchat的滤镜和表情包。

这种情况可能即将发生改变。在这个远程办公和混合办公的时代,希望在线上重新营造办公环境的企业正在考虑在工作环境中采用虚拟形象。比如,Facebook最近发布的Horizon Workrooms是一款正在测试中的虚拟现实应用程序,它可以让员工构建自己的虚拟形象,然后主持线上的头脑风暴会议。全员会议全体以虚拟形象参加的那一天,应该不会很遥远吧。

多家知名品牌也开始采用各种虚拟形象。今年4月,Netflix推出了自己的虚拟形象——一个名为“N-Ko”的绵羊人——为即将推出的动漫产品宣传造势。7月,索尼音乐(Sony Music)宣布围绕旗下音乐、配音和其他数字内容对50位日语“虚拟达人”进行试镜。

制约虚拟主播发展的可能不是虚拟形象本身,而是它与有时杂乱无章的流媒体亚文化的关联性。机构要允许旗下的虚拟主播人才表达自我,与粉丝交流互动,也要保持良好形象,让知名品牌放心合作。它们必须要在这两点之间取得平衡。

虽然虚拟主播现象在全球各地内持续流行开来,但西方虚拟主播仍然没有日本虚拟主播红火。根据Stream Hatchet的数据,8月份排名前10的虚拟主播中只有3个是英语主播。然而,虚拟主播已经打入了西方的直播消费市场。正如Stream Hatchet营销经理贾斯汀·罗斯柴尔德所说:“如果虚拟主播能够在Twitch(主要依托北美市场的平台)上取得成功,那么就没有它们无法触及的直播市场,那也会为它们获得更多的观众、赞助合同和增长机会打开大门。”

在经历了一年半的居家生活后,国外观众对虚拟主播的接受度越来越高。上线仅仅几周,Hololive的其中一位第二代英文主播就已经拥有超过37.5万的订阅者。(财富中文网)

译者:万志文

在痴迷棒球的日本,两大职业棒球联盟之一的太平洋联盟(Pacific Baseball League)于今年8月宣布了一项特别推广活动,其中涉及一系列新的球队吉祥物。这些吉祥物包括12位以日本标志性动漫风格绘制的女性角色。

采用动漫角色进行营销推广在日本十分普遍。原创和经过授权的动漫角色被用于宣传产品、商品、服务和各类活动,其中包括2021年东京奥运会(2021 Tokyo Olympics)。

然而,日本棒球联盟所采用的角色有所不同,因为它们在某种程度上是真实的人。

每个角色都是“虚拟主播”经纪公司Hololive旗下的日语主播,虚拟主播是真实的表演者或“达人”在网络上的虚拟形象。隶属于日本公司Cover Corp的Hololive规模位居行业前列,旗下的57名虚拟主播的订阅用户总量高达4300万。除此之外,现在有成千上万的虚拟主播已经将触角伸向中国、韩国、印度尼西亚、美国等市场。

虚拟主播最初被视为日本数字文化中的奇葩,但在过去一年里,它在全球各地越来越受欢迎。新冠肺炎疫情期间,居家隔离的人们普遍在网上寻找娱乐,数百万人选择观看各类直播活动——包括虚拟主播亚文化。

YouTube的官方数据显示,2020年10月,虚拟主播主页每月的播放量达到15亿次。“虽然各种流媒体趋势来来去去,但虚拟主播内容在过去一年一直保持着相当可观的播放量。”流媒体分析公司Stream Hatchet的首席执行官爱德华·蒙特塞拉特指出。

其中最受欢迎的虚拟主播之一是来自日本的Usada Pekora,她之所以走红,是因为她会玩经典的日本角色扮演游戏,常常在《我的世界》(Minecraft)中恶搞其他的虚拟主播,还与印度尼西亚的一位虚拟主播建立了深厚的友谊,尽管双方都不会流利地说对方的语言。根据Stream Hatchet的数据,Pekora是2021年第二季度播放量第三高的女主播。

深厚且忠诚的粉丝基础促使这些达人成为数字明星,尽管——或者可能是因为——他们是以相对匿名的方式藏在虚拟形象背后表演。粉丝们都非常乐意帮助虚拟主播塑造“角色形象”,无论是通过提供翻译服务来开拓新市场,还是打赏支持。

根据Playboard的数据,在从粉丝获得“Superchat”打赏最多的20个YouTube频道中,有17个是虚拟主播。

“最近虚拟主播内容的激增对全球流媒体社区来说并不新鲜,毕竟它在亚洲各大流媒体网站上很受欢迎,在Twitch等西方平台上的播放量也在持续走高。”蒙特塞拉特补充道。

同样引人瞩目的是,一种新型的广告公司正在毫不犹豫地利用这波热潮谋利。

虚拟主播究竟是什么?

从某种意义上说,虚拟主播与常见的主播没有什么不同。这些表演者会玩电子游戏、录制各种反应视频、直播日常活动,并与粉丝交流互动,就像YouTube、Twitch、中国的哔哩哔哩等平台上的其他主播一样。

然而,普通主播可能会以自己的名义发布内容,并在镜头前展示自己的真容,而虚拟主播则是藏在虚拟形象背后进行流媒体直播。借助面部识别和动作捕捉技术,虚拟形象会模仿表演者的表情和动作。虚拟主播还经常用假名表演,在观众和实际表演者之间多增加一层屏障。虚拟主播不一定是匿名的——其真实身份有可能被“人肉”出来——但是主播及其粉丝不鼓励讨论虚拟形象背后的人。

虽然虚拟主播早在21世纪10年代初便出现在YouTube上,但直到Kizuna AI出现,并没有虚拟主播真正走红。Kizuna背后的日本声优春日望现年26岁,在“现实世界”中也颇受欢迎。她主持过电视节目,曾经登上杂志封面,甚至担任过日本国家旅游局(Japan’s National Tourism Organization)的代言人。

廉价的面部识别和运动跟踪软件的发展,催生出了大量独立的虚拟主播。但在许多人看来,是Kizuna AI促使这一数字现象变成一门大生意的;几家专门为虚拟主播提供服务的经纪公司没有多久便应运而生,其中包括Cover Corp的Hololive和Anycolor的Nijisanji。

经纪公司为虚拟主播提供基础设施,在后者与Twitch、YouTube等平台打交道时提供技术和法律上的支持;它们还与其他公司签订营销推广协议,比如Hololive对日清(Nissin)的Curry Meshi杯面的宣传推广。

国际吸引力

2020年10月,Hololive推出了第一批主要讲英语的虚拟主播。这些主播的订阅用户数量增长惊人,短短几周便迅速超过了日语主播。其他机构随即跟风:VShojo总部位于旧金山,由Twitch创始团队的一名成员创立,2020年11月面世时便主打一大批英语虚拟主播。其竞争对手Nijisanji也于今年5月上线了自己的英语虚拟主播。

在此之前,全球各地对虚拟直播的兴趣日渐浓厚。日本的经纪机构早就已经开始探索国际扩张,在中国、韩国和印度尼西亚等国招兵买马。与此同时,日语虚拟主播经过译制的内容开始在4Chan、Reddit等海外平台上传播开来。日本的双语主播也开始更多地与国际观众展开互动。

今年早些时候,英语虚拟主播——鲨鱼女孩Gawr Gura——超过了Kizuna AI,成为全球订阅人数最多的虚拟主播。

与此同时,各家经纪机构继续在西方市场开疆辟土:Hololive和Nijisanji均在2021年推出了第二代英语虚拟主播。

走红后的麻烦

虚拟主播——或者更准确地说,虚拟形象背后的表演者——面临着许多与传统主播一样的问题,从在线骚扰和平台运营商的专横决定,到侵犯版权和倦怠。

有的虚拟主播甚至触犯政治红线。

此外,经纪公司可能永久拥有特定虚拟形象或其作品的版权,哪怕最初推广该形象的表演者不再为之效力了(或者,用一家机构的委婉说法,“毕业了”)。与机构不欢而散的表演者会发现他们的视频内容最终被隐匿起来,乃至完全删除。

但是,机构仍然要考虑粉丝的期望和感受。例如,机构之前让Kizuna AI出现在由多个配音演员负责的多个频道,此举引发了粉丝的强烈反对,他们要求用回原配音演员,以消除她要被淘汰的传言。

虚拟主播的未来

尽管近期出现了令人惊艳的增长,但虚拟主播——甚至是虚拟形象这一大概念——并没有引起大多数西方观众的注意,他们更热衷于使用Snapchat的滤镜和表情包。

这种情况可能即将发生改变。在这个远程办公和混合办公的时代,希望在线上重新营造办公环境的企业正在考虑在工作环境中采用虚拟形象。比如,Facebook最近发布的Horizon Workrooms是一款正在测试中的虚拟现实应用程序,它可以让员工构建自己的虚拟形象,然后主持线上的头脑风暴会议。全员会议全体以虚拟形象参加的那一天,应该不会很遥远吧。

多家知名品牌也开始采用各种虚拟形象。今年4月,Netflix推出了自己的虚拟形象——一个名为“N-Ko”的绵羊人——为即将推出的动漫产品宣传造势。7月,索尼音乐(Sony Music)宣布围绕旗下音乐、配音和其他数字内容对50位日语“虚拟达人”进行试镜。

制约虚拟主播发展的可能不是虚拟形象本身,而是它与有时杂乱无章的流媒体亚文化的关联性。机构要允许旗下的虚拟主播人才表达自我,与粉丝交流互动,也要保持良好形象,让知名品牌放心合作。它们必须要在这两点之间取得平衡。

虽然虚拟主播现象在全球各地内持续流行开来,但西方虚拟主播仍然没有日本虚拟主播红火。根据Stream Hatchet的数据,8月份排名前10的虚拟主播中只有3个是英语主播。然而,虚拟主播已经打入了西方的直播消费市场。正如Stream Hatchet营销经理贾斯汀·罗斯柴尔德所说:“如果虚拟主播能够在Twitch(主要依托北美市场的平台)上取得成功,那么就没有它们无法触及的直播市场,那也会为它们获得更多的观众、赞助合同和增长机会打开大门。”

在经历了一年半的居家生活后,国外观众对虚拟主播的接受度越来越高。上线仅仅几周,Hololive的其中一位第二代英文主播就已经拥有超过37.5万的订阅者。(财富中文网)

译者:万志文

The Japanese Pacific Baseball League, one of two major professional baseball leagues in baseball-obsessed Japan, announced a special promotion in August involving a series of new team mascots. The lineup included twelve female characters drawn in Japan’s signature anime-style.

Using anime characters as marketing tools is common throughout Japan. Original and licensed anime characters are used to advertise products, merchandise, services and events, including the 2021 Tokyo Olympics.

Yet the characters featured in Japan’s baseball league were different in that they were real people—well, kind of.

Each character was a Japanese streamer managed by Hololive, a talent agency specializing in “VTubers”: a digital avatar brought to life online, so to speak, by a real-life presenter, or "talent." Hololive, owned by Japan-based Cover Corp, is one of the largest of these agencies, with 43 million subscribers across its 57 talents. Beyond that, thousands of VTubers now stream in markets like China, South Korea, Indonesia and the United States.

What was originally viewed as an oddity of Japan’s digital culture has risen in global popularity over the past year. People stuck at home during COVID-19 lockdowns looked online for entertainment, and millions turned to livestreams—including the VTuber subculture.

By October 2020, VTubers were attracting 1.5 billion views per month, YouTube data shows. “While various streaming trends come and go, VTuber content has maintained considerable viewership over the past year,” says Eduard Montserrat, CEO of the streaming analytics firm, Stream Hatchet.

One of those most popular is Usada Pekora, a Japanese VTuber, best known for playing classic Japanese role-playing games, playing pranks on her fellow streamers in Minecraft, and a deep friendship with an Indonesian VTuber colleague despite neither fluently speaking the other's language. Pekora was, according to Stream Hatchet data, the third most-watched female streamer of the second quarter of 2021.

A deep and engaged fanbase pushes these talents to digital stardom, and that's despite—or perhaps because of—performing in relative anonymity, behind an avatar. Fans are all too happy to help VTuber's build out the "character," whether it be by offering translation services to crack new markets, or throwing in financial support.

According to data from Playboard, out of the top twenty YouTube channels that have received the most "Superchat" donations from fans, seventeen are VTubers.

"The recent surge in VTuber content is not new to the global streaming community, as it has been popular on [Asian] streaming sites, but [it's] also increasing in viewership on Western sites like Twitch," adds Monserrat.

Just as impressively, a new breed of ad agency is wasting no time commercializing the craze.

What exactly is VTubing?

In one sense, a VTuber—short for “virtual YouTuber”—is little different from your regular streamer. These entertainers play video games, record reaction videos, stream their daily activities, and interact with their fans, much like other streamers on YouTube, Twitch, China’s Billibilli and other platforms.

But while a regular streamer may release content under his own name and show himself on camera, a VTuber instead streams behind the cloak of a digital avatar. The avatar, using facial recognition and motion capture technology, emulates the expressions and movements of the performer. VTubers also often perform under assumed names, putting an additional barrier between the audience and the actual performer. VTubers aren't necessarily anonymous—dedicated research could unmask a VTuber's 'previous life'—but discussion of the person behind the avatar is discouraged by the streamers and their fans.

While digital avatars had been present on YouTube since the early 2010s, the first VTuber to achieve real popularity was Kizuna AI. Kizuna, portrayed by Nozomi Kasuga, a Japanese voice actor who turned 26 this year, was also a hit in the “real world.” She hosted television shows, graced magazine covers, and even acted as spokesperson for Japan’s National Tourism Organization.

The development of cheap facial recognition and motion-tracking software has given rise to a vast number of independent VTubers. But many credit Kizuna AI for pushing the digital phenomenon into a major business; several talent agencies dedicated to VTubers later appeared soon after, including Cover Corp’s Hololive and Anycolor’s Nijisanji.

Talent agencies provide infrastructure, plus the tech and legal support for dealing with platforms like Twitch and YouTube; they also sign marketing deals with other companies, such as Hololive’s—somewhat manic—promotion of Nissin's Curry Meshi cup noodles.

International appeal

In October 2020, Hololive launched the first cohort of primarily English-speaking VTubers. The streamers saw explosive subscriber growth, quickly overtaking their Japanese counterparts in a matter of weeks. They were soon followed by other agencies: VShojo, based in San Fancisco and launched by a member of Twitch's founding team, debuted in November 2020 with a cohort of exclusively English-streaming talent. Rival agency Nijisanji launched its own English-speaking cohort in May.

Before these launches, global interest in VTubing had been building. Japan’s talent agencies had already started to explore international expansion, hiring talent in China, Korea and Indonesia. Meanwhile, translated clips of Japanese VTubers were starting to go viral on platforms like 4Chan and Reddit. Bilingual entertainers in Japan were also starting to engage more with their international audiences.

Earlier this year, an English-speaking VTuber—the miniature shark-girl Gawr Gura—overtook Kizuna AI to become the world’s most subscribed VTuber.

Agencies, meanwhile, continue to expand in Western markets: both Hololive and Nijisanji launched second generations of English talent in 2021.

With stardom, come problems

VTubers—or, more accurately, the performers behind the digital mask—face many of the same problems of traditional streamers, from online harassment and arbitrary decisions by platform operators to running afoul of copyright and just general burnout.

VTubers have even crossed geopolitical lines.

Additionally, agencies may own the rights to a particular avatar or their work even after the original performer who popularized it leaves (or, as one agency euphemistically calls it, “graduating”). Performers who leave the agency on bad terms can see their videos "privated," erasing entire bodies of work.

However, agencies still have to consider fan expectations. In one example, efforts to expand Kizuna AI’s presence to multiple channels—handled by multiple voice actors—led to a fan backlash that required the original voice actor to return to dismiss rumors that she was being phased out.

The future of VTubing

Despite the impressive recent growth, VTubers—and even the larger idea of digital avatars—fly under the radar of most Western audiences who instead spend their time with Snapchat filters and animated emojis.

That may be about to change. Companies looking to revive a semblance of an office environment in an age of remote and hybrid work are mulling the use of avatars in more professional settings. Facebook’s recently announced “Horizon Workrooms,” for example, is a virtual reality app in beta that would allow a worker to construct a digital avatar of herself who would then lead a virtual brainstorming meeting. Could all-hands virtual meetings populated by you and your colleagues, all in avatar form, be that far behind?

And, established brands are adopting all manner of virtual avatars. Netflix launched its own digital character in April—a "sheep-human lifeform" named N-Ko—to advertise upcoming anime offerings. And in July, Sony Music announced auditions for 50 Japanese "virtual talents" for music, voice-acting, and other digital content.

What limits VTubing is perhaps not the digital avatar itself, but rather its connection to the sometimes rough-and-tumble streaming subculture. Agencies have to balance giving their talent the permission to express themselves and communicate with their fans—sometimes in ways that cross into not-safe-for-work territory—and preserving an image that established brands feel comfortable attaching themselves to.

While the phenomenon continues to catch on globally, Western VTubers still lag their Japanese counterparts in popularity. According to Stream Hatchet, only three of August’s top 10 VTubers are English-speakers. Yet VTubers have broken into Western livestreaming consumption. As Justin Rothschild, marketing manager for Stream Hatchet notes, “If VTubers can succeed on Twitch [a primarily North American platform], there doesn't exist a live streaming market they can't reach; opening doors to even bigger audiences, sponsorship deals, and growth opportunities."

After a year and a half of life mainly indoors, foreign audiences are becoming increasingly receptive to the VTubing trend. Just a few weeks after debuting, one of Hololive’s second generation of English streamers already had over 375,000 subscribers.