2022年,在美国得克萨斯州的圣安东尼奥,阿图罗·博尼拉博士小心翼翼地将一只外耳植入到一名20岁女子的身上,这名女子天生缺少一只外耳。右侧植入的外耳是按照她左侧外耳的大小和形状构建的。

博尼拉是一位有着25年以上经验的小耳畸形外科医生(治疗耳部先天缺陷的医生),也是该领域公认的专家,对他来说,这样的手术很常规。但这个案例令人意想不到的点在于这是他首次将3D打印的耳朵(利用该女子自身的软骨细胞)植入人体。

博尼拉告诉我,植入手术“非常顺利”。总而言之,说手术非常顺利,那绝对是轻描淡写。

从近乎虚构走向萌芽,再走到真实的科学研究,3D生物打印应用于医学研究的方方面面都取得了进展,如今,3D生物打印正在实践方面取得进步。虽然进展缓慢,一些宏大的3D计划设定的目标日期是在几十年后,但3D生物打印着实取得了实实在在的进步。

位于以色列的特拉维夫大学(Tel Aviv University)的组织工程和再生医学主任塔尔·德维尔教授说:“我认为在10年内,我们能够打印出用于移植的器官。我们将从像皮肤和软骨这样的简单器官开始,然后转向更复杂的组织——最终的目标是打印心脏、肝脏和肾脏。”

3D生物打印的未来

这听起来很玄乎,但已经成为现实了。多层皮肤、骨骼、肌肉结构、血管、视网膜组织,甚至微器官都已经被3D打印出来了。虽然这些打印出来的组织还没有被批准用于人体,但科学发展的进程令人叹为观止——博尼拉的耳朵手术是首次将3D打印的耳朵(利用活细胞)植入人体,这是一大里程碑事件。

根据2022年的一份摘要和仿生胰腺的制造者米哈尔·弗绍瓦博士的介绍,波兰的研究人员生物打印了一个具备各种功能的胰腺原型,在观察的两周时间里,猪体内血液流动稳定。United Therapeutics Corporation已经 3D打印了一个人类肺部支架,毛细血管全长达4,000千米,还有2亿个肺泡(微小的气囊),可以在动物模型中进行氧气交换,这是制造可耐受、可移植的人类肺部的关键一步,该公司的目标是让打印的人类肺部支架在五年内被批准用于人体试验。

在维克森林大学再生医学研究所(Wake Forest University Institute for Regenerative Medicine),科学家们开发了一种移动式皮肤生物打印系统。在不久的将来,他们预计能够直接把打印机推到伤口难以愈合(例如烧伤)的患者床边,然后扫描和测量伤口面积,并将3D打印的皮肤一层一层地直接打印到患者的伤口表面。他们还进行了深入研究,3D打印的骨骼肌构建体已被证明可以在啮齿动物身上实现收缩功能,而且胫骨前肌80%以上先前丧失的肌肉功能能够在八周内得到恢复。

德维尔自己的实验室已经3D打印出一颗“兔子心脏大小”的心脏,正如他所说的,这颗心脏充满细胞、心室和主要血管,还可以和心脏一样跳动。教授指出,尽管按照比例放大的过程非常复杂,但打印全尺寸的人类心脏需要采用同样的基本技术。“我们如今正在研究起搏细胞、心房肌细胞和心室肌细胞。”德维尔表示。“目前看起来进展不错。我相信这就是3D生物打印的未来。”

3D生物打印是如何工作的

3D打印人体器官这样的概念令人震惊。根据美国联邦卫生资源和服务管理局(Health Resources and Services Administration)的数据,目前有近10.6万美国人正在等待器官移植,每天有17人在等待器官移植时死亡。利用患者自身细胞培育器官的3D打印技术不仅可能导致等待器官移植的患者减少,还会大大降低器官移植排异的几率,并可能消除终生服用对身体有害的免疫抑制药物的需求。

斯坦福大学(Stanford University)的生物工程系助理教授马克·斯凯拉-斯科特说:“两项(3D)技术为组织工程领域带来重大革新,一是将不同类型的细胞放置在精确的位置以构建复杂组织,二是整合血管以输送必要的氧气和营养物质来保持细胞存活。在过去的20年里,该领域发展非常迅速,从打印膀胱到如今能够打印带有可以与泵相连的血管的复杂组织,以及类似于带有集成各种心肌细胞的心脏组织的复杂3D模型。”

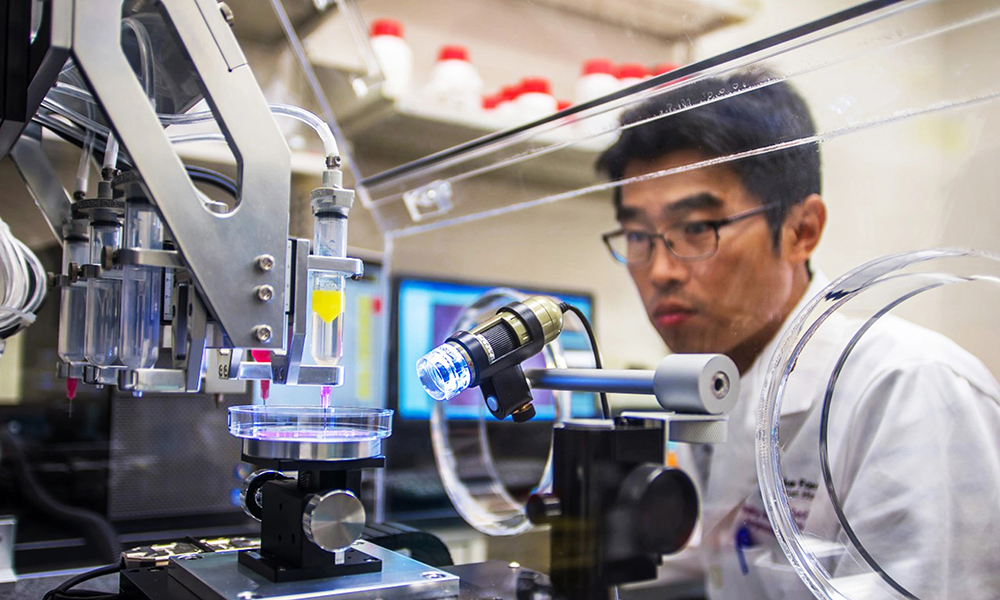

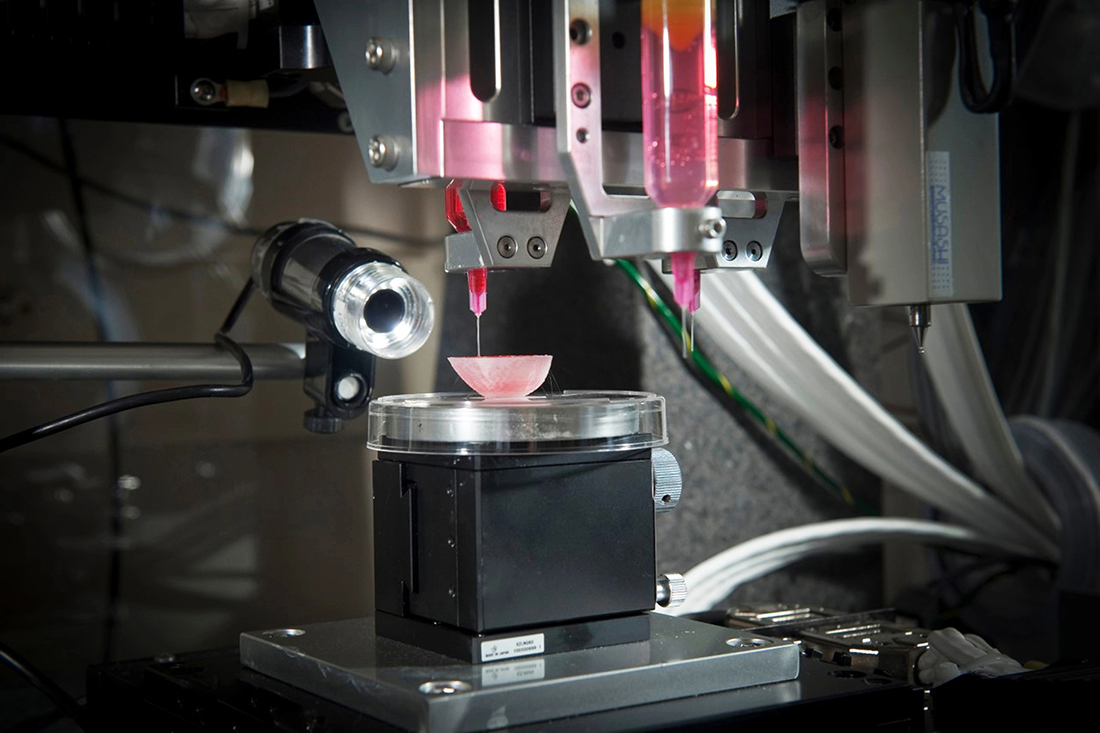

在3D生物打印中,最重要的部分就是细胞。就3D生物打印过程而言,首先是生成研究人员想要生物打印的细胞,然后指示它们形成特定器官细胞类型。然后,这些细胞被制成能够打印的活墨水或生物墨水,包括将它们与明胶或海藻酸盐等材料混合,以使它们具有类似牙膏的粘度。斯坦福大学的实验室正在研究,高密度地挤在一起的干细胞是如何自然地形成这种粘度的,这可能会导致3D打印器官完全由患者自身的细胞制成。

斯凯拉-斯科特指出,生物墨水被装入注射器,然后“就像蛋糕上的糖霜”一样从喷头中挤出。这是真正的3D生物打印过程,它通常包括放置不同类型的细胞,每个细胞都被装入不同的喷头。(德维尔说,打印这个迷你心脏花了大约4个小时。)一旦完成,组织有时会被连接到一个泵上,这样就可以为该组织输送氧气和营养物质。随着时间的推移,该组织就会自行发育,成熟度会不断提高,功能也会更加完善。

这个大致的过程,虽然在这里被大大简化了,但阿图罗·博尼拉医生在得克萨斯州将这个过程的产物——打印的外耳——植入患者。在以前的大多数小耳畸形手术里,博尼拉会从患者肋骨上提取软骨,将其雕刻成耳朵的大致形状。这一次,博尼拉在患者的另一只耳朵上进行了一个小的活检,从活检中提取的软骨细胞被培养成数十亿个细胞,这些细胞被3D打印成了新的植入物。

博尼拉说:“与任何研究一样,为了尝试改进这项技术,未来的患者可能会经历迭代。我们不确定这将在何时成为主要治疗方法,但该技术的未来是非常激动人心的。”

3D打印的优势

维克森林大学的科学家多年来一直在实验室培育器官和组织。他们在实验室里用3D打印技术制造了一个迷你肾脏和一个迷你肝脏。下一个挑战:更大的、可以更充分地模拟器官功能的实心结构。“在器官尺寸上,我们离实现这一目标还有很长一段路要走。”哈佛大学(Harvard University)怀斯生物启发工程研究所(Biologically Inspired Engineering)的教授詹妮弗·刘易斯表示。

“我们已经能够打印出像皮肤这样的平面结构,像血管这样的管状结构,或者像膀胱这样的空心非管状器官。”维克森林研究所的创始主任安东尼·阿塔拉说。“由于血管和营养方面的挑战”,打印更大的实心器官是不同的,毕竟“每厘米就有非常多细胞。”

在细胞制造的某些方面,还存在质量问题。科学家们已经可以从干细胞中制造出心肌细胞,但制造出的心肌细胞无法像你的心肌细胞那样强烈地跳动。肝细胞(代谢)和肾细胞(滤液摄取)的情况也是如此。斯凯拉-斯科特称:“从某些方面讲,3D生物打印领域正在等待基础生物学家取得重大突破。”

还有一个问题是数量问题。制造一颗心脏需要“数十亿个细胞——而且需要不同的细胞,甚至是不同的心肌细胞。”塔尔·德维尔说道。根据斯凯拉-斯科特的说法,要为一个器官制造足够的细胞,制造厂需要一个10升的搅拌缸,每天可能要花费5,000美元,而且需要连续几个月才能够完成。最终目标是每个月培育上千个器官,而不是一个器官。

3D Bio Therapeutics的首席执行官及联合创始人丹·科恩表示,除此之外,还有组织如何融入人体以及如何得到人体的支持等问题,包括复杂的血管、神经和多种细胞类型网络。“这并不是说这一点无法做到。”科恩说,他20年前就开始在生物打印领域工作,当时这个领域连个正式的名字都没有。“我对生物打印和再生医学的广泛应用抱有很大希望。”

就短期而言,进展也是非常显著的。刘易斯表示,哈佛大学的研究人员从人类多能干细胞中培育出心肌细胞,然后将它们植入带有传感器(这些传感器可以追踪跳动的组织)的生物工程芯片上。这种3D打印的芯片上的心脏能够用于测试各种心脏药物的潜在毒副作用,并可能减轻对动物试验的需求。(类似的芯片上的肌萎缩性侧索硬化症技术正在被用于筛选候选药物,这样也可以更好地了解这种疾病的潜在机制。)

维克森林大学的阿塔拉说:“3D打印机有几大优点。首先是能够扩大规模,因为你可以用打印机自动化打印(组织和器官),而不是手工一次完成一个。其次是能够确保精确度。我们可以更精确地将细胞放置在需要它们的地方。”

再有一点就是能够降低整体成本,这是因为3D打印允许加大规模。这就是阿塔拉所说的“可重复性”(一种可以反复制造相同结构的方法)。在器官移植方面,由患者自身细胞制成的新器官能够大大降低排异反应的可能性。

大多数研究人员认为,全尺寸3D打印人体器官移植还需要20年到30年的时间。“展望未来,我们将无需接受心脏捐赠,也无需接受肝脏捐赠。”德维尔说。“这是我的观点,而且我很乐观,我认为在不到20年的时间里,就会出现打印的器官被植入患者体内。”这是科学在发挥作用,而不是科幻小说。(财富中文网)

译者:中慧言-王芳

2022年,在美国得克萨斯州的圣安东尼奥,阿图罗·博尼拉博士小心翼翼地将一只外耳植入到一名20岁女子的身上,这名女子天生缺少一只外耳。右侧植入的外耳是按照她左侧外耳的大小和形状构建的。

博尼拉是一位有着25年以上经验的小耳畸形外科医生(治疗耳部先天缺陷的医生),也是该领域公认的专家,对他来说,这样的手术很常规。但这个案例令人意想不到的点在于这是他首次将3D打印的耳朵(利用该女子自身的软骨细胞)植入人体。

博尼拉告诉我,植入手术“非常顺利”。总而言之,说手术非常顺利,那绝对是轻描淡写。

从近乎虚构走向萌芽,再走到真实的科学研究,3D生物打印应用于医学研究的方方面面都取得了进展,如今,3D生物打印正在实践方面取得进步。虽然进展缓慢,一些宏大的3D计划设定的目标日期是在几十年后,但3D生物打印着实取得了实实在在的进步。

位于以色列的特拉维夫大学(Tel Aviv University)的组织工程和再生医学主任塔尔·德维尔教授说:“我认为在10年内,我们能够打印出用于移植的器官。我们将从像皮肤和软骨这样的简单器官开始,然后转向更复杂的组织——最终的目标是打印心脏、肝脏和肾脏。”

3D生物打印的未来

这听起来很玄乎,但已经成为现实了。多层皮肤、骨骼、肌肉结构、血管、视网膜组织,甚至微器官都已经被3D打印出来了。虽然这些打印出来的组织还没有被批准用于人体,但科学发展的进程令人叹为观止——博尼拉的耳朵手术是首次将3D打印的耳朵(利用活细胞)植入人体,这是一大里程碑事件。

根据2022年的一份摘要和仿生胰腺的制造者米哈尔·弗绍瓦博士的介绍,波兰的研究人员生物打印了一个具备各种功能的胰腺原型,在观察的两周时间里,猪体内血液流动稳定。United Therapeutics Corporation已经 3D打印了一个人类肺部支架,毛细血管全长达4,000千米,还有2亿个肺泡(微小的气囊),可以在动物模型中进行氧气交换,这是制造可耐受、可移植的人类肺部的关键一步,该公司的目标是让打印的人类肺部支架在五年内被批准用于人体试验。

在维克森林大学再生医学研究所(Wake Forest University Institute for Regenerative Medicine),科学家们开发了一种移动式皮肤生物打印系统。在不久的将来,他们预计能够直接把打印机推到伤口难以愈合(例如烧伤)的患者床边,然后扫描和测量伤口面积,并将3D打印的皮肤一层一层地直接打印到患者的伤口表面。他们还进行了深入研究,3D打印的骨骼肌构建体已被证明可以在啮齿动物身上实现收缩功能,而且胫骨前肌80%以上先前丧失的肌肉功能能够在八周内得到恢复。

德维尔自己的实验室已经3D打印出一颗“兔子心脏大小”的心脏,正如他所说的,这颗心脏充满细胞、心室和主要血管,还可以和心脏一样跳动。教授指出,尽管按照比例放大的过程非常复杂,但打印全尺寸的人类心脏需要采用同样的基本技术。“我们如今正在研究起搏细胞、心房肌细胞和心室肌细胞。”德维尔表示。“目前看起来进展不错。我相信这就是3D生物打印的未来。”

3D生物打印是如何工作的

3D打印人体器官这样的概念令人震惊。根据美国联邦卫生资源和服务管理局(Health Resources and Services Administration)的数据,目前有近10.6万美国人正在等待器官移植,每天有17人在等待器官移植时死亡。利用患者自身细胞培育器官的3D打印技术不仅可能导致等待器官移植的患者减少,还会大大降低器官移植排异的几率,并可能消除终生服用对身体有害的免疫抑制药物的需求。

斯坦福大学(Stanford University)的生物工程系助理教授马克·斯凯拉-斯科特说:“两项(3D)技术为组织工程领域带来重大革新,一是将不同类型的细胞放置在精确的位置以构建复杂组织,二是整合血管以输送必要的氧气和营养物质来保持细胞存活。在过去的20年里,该领域发展非常迅速,从打印膀胱到如今能够打印带有可以与泵相连的血管的复杂组织,以及类似于带有集成各种心肌细胞的心脏组织的复杂3D模型。”

在3D生物打印中,最重要的部分就是细胞。就3D生物打印过程而言,首先是生成研究人员想要生物打印的细胞,然后指示它们形成特定器官细胞类型。然后,这些细胞被制成能够打印的活墨水或生物墨水,包括将它们与明胶或海藻酸盐等材料混合,以使它们具有类似牙膏的粘度。斯坦福大学的实验室正在研究,高密度地挤在一起的干细胞是如何自然地形成这种粘度的,这可能会导致3D打印器官完全由患者自身的细胞制成。

斯凯拉-斯科特指出,生物墨水被装入注射器,然后“就像蛋糕上的糖霜”一样从喷头中挤出。这是真正的3D生物打印过程,它通常包括放置不同类型的细胞,每个细胞都被装入不同的喷头。(德维尔说,打印这个迷你心脏花了大约4个小时。)一旦完成,组织有时会被连接到一个泵上,这样就可以为该组织输送氧气和营养物质。随着时间的推移,该组织就会自行发育,成熟度会不断提高,功能也会更加完善。

这个大致的过程,虽然在这里被大大简化了,但阿图罗·博尼拉医生在得克萨斯州将这个过程的产物——打印的外耳——植入患者。在以前的大多数小耳畸形手术里,博尼拉会从患者肋骨上提取软骨,将其雕刻成耳朵的大致形状。这一次,博尼拉在患者的另一只耳朵上进行了一个小的活检,从活检中提取的软骨细胞被培养成数十亿个细胞,这些细胞被3D打印成了新的植入物。

博尼拉说:“与任何研究一样,为了尝试改进这项技术,未来的患者可能会经历迭代。我们不确定这将在何时成为主要治疗方法,但该技术的未来是非常激动人心的。”

3D打印的优势

维克森林大学的科学家多年来一直在实验室培育器官和组织。他们在实验室里用3D打印技术制造了一个迷你肾脏和一个迷你肝脏。下一个挑战:更大的、可以更充分地模拟器官功能的实心结构。“在器官尺寸上,我们离实现这一目标还有很长一段路要走。”哈佛大学(Harvard University)怀斯生物启发工程研究所(Biologically Inspired Engineering)的教授詹妮弗·刘易斯表示。

“我们已经能够打印出像皮肤这样的平面结构,像血管这样的管状结构,或者像膀胱这样的空心非管状器官。”维克森林研究所的创始主任安东尼·阿塔拉说。“由于血管和营养方面的挑战”,打印更大的实心器官是不同的,毕竟“每厘米就有非常多细胞。”

在细胞制造的某些方面,还存在质量问题。科学家们已经可以从干细胞中制造出心肌细胞,但制造出的心肌细胞无法像你的心肌细胞那样强烈地跳动。肝细胞(代谢)和肾细胞(滤液摄取)的情况也是如此。斯凯拉-斯科特称:“从某些方面讲,3D生物打印领域正在等待基础生物学家取得重大突破。”

还有一个问题是数量问题。制造一颗心脏需要“数十亿个细胞——而且需要不同的细胞,甚至是不同的心肌细胞。”塔尔·德维尔说道。根据斯凯拉-斯科特的说法,要为一个器官制造足够的细胞,制造厂需要一个10升的搅拌缸,每天可能要花费5,000美元,而且需要连续几个月才能够完成。最终目标是每个月培育上千个器官,而不是一个器官。

3D Bio Therapeutics的首席执行官及联合创始人丹·科恩表示,除此之外,还有组织如何融入人体以及如何得到人体的支持等问题,包括复杂的血管、神经和多种细胞类型网络。“这并不是说这一点无法做到。”科恩说,他20年前就开始在生物打印领域工作,当时这个领域连个正式的名字都没有。“我对生物打印和再生医学的广泛应用抱有很大希望。”

就短期而言,进展也是非常显著的。刘易斯表示,哈佛大学的研究人员从人类多能干细胞中培育出心肌细胞,然后将它们植入带有传感器(这些传感器可以追踪跳动的组织)的生物工程芯片上。这种3D打印的芯片上的心脏能够用于测试各种心脏药物的潜在毒副作用,并可能减轻对动物试验的需求。(类似的芯片上的肌萎缩性侧索硬化症技术正在被用于筛选候选药物,这样也可以更好地了解这种疾病的潜在机制。)

维克森林大学的阿塔拉说:“3D打印机有几大优点。首先是能够扩大规模,因为你可以用打印机自动化打印(组织和器官),而不是手工一次完成一个。其次是能够确保精确度。我们可以更精确地将细胞放置在需要它们的地方。”

再有一点就是能够降低整体成本,这是因为3D打印允许加大规模。这就是阿塔拉所说的“可重复性”(一种可以反复制造相同结构的方法)。在器官移植方面,由患者自身细胞制成的新器官能够大大降低排异反应的可能性。

大多数研究人员认为,全尺寸3D打印人体器官移植还需要20年到30年的时间。“展望未来,我们将无需接受心脏捐赠,也无需接受肝脏捐赠。”德维尔说。“这是我的观点,而且我很乐观,我认为在不到20年的时间里,就会出现打印的器官被植入患者体内。”这是科学在发挥作用,而不是科幻小说。(财富中文网)

译者:中慧言-王芳

Last year, in San Antonio, Texas, Dr. Arturo Bonilla carefully implanted an outer ear on a 20-year-old woman born without one. The ear on the woman’s right side, had been constructed in the size and shape of her left.

For Bonilla, a pediatric microtia surgeon (a doctor who treats birth defects of the ear) for more than 25 years and a recognized expert in the field, such a procedure would normally be routine. But this case had a twist: For the first time, the ear he was implanting was the product of a 3D bioprinter using the woman’s own cartilage cells.

The implant procedure, Bonilla told me, was “very uneventful.” It is a vast understatement, all things considered.

From the realm of near-fiction to the germ of an idea to actual science, 3D bioprinting is advancing across all aspects of medical research—and, now, practice. The pace is slow, and target dates for some of the most ambitious 3D plans are decades off. But progress is real.

“I think that in 10 years we will have organs for transplantation,” says professor Tal Dvir, director of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine at Tel Aviv University in Israel. “We will start with simple organs like skin and cartilage, but then we’ll move on to more complicated tissues—eventually the heart, liver, kidney.”

The future of 3D bioprinting

It sounds fantastical, but it’s already happening. Multilayered skin, bones, muscle structures, blood vessels, retinal tissue and even mini-organs all have been 3D printed. While none of the printed products are yet approved for human use, the race up the scientific timeline is breathtaking—and Bonilla’s ear procedure, the first 3D bioprint from live cells to be implanted in a human, marks a significant moment along that progression.

Researchers in Poland bioprinted a functional prototype of a pancreas in which stable blood flow was achieved in pigs during an observed two-week period, according to a 2022 abstract and Dr. Michal Wszola, creator of Bionic Pancreas. United Therapeutics Corporation has 3D printed a human lung scaffold with 4,000 kilometers of capillaries and 200 million alveoli (tiny air sacs) that are capable of oxygen exchange in animal models—a critical step toward creating tolerable, transplantable human lungs with the goal of being cleared for human trials within five years.

At Wake Forest University Institute for Regenerative Medicine, scientists have developed a mobile skin bioprinting system. In the not-too-distant future, they anticipate being able to roll the printer right to the bedside of a patient suffering from a non-healing wound, such as a burn, then scan and measure the wound area and 3D print skin, layer by layer, directly onto the wound surface. And they’ve gone deeper, 3D printing skeletal muscle constructs that have been shown to contract in rodents and regain more than 80% of previously lost muscular function in an anterior leg muscle within eight weeks.

Dvir’s own lab has produced a 3D-printed “rabbit-sized” heart, as he puts it, replete with cells, chambers, the major blood vessels and a heartbeat. Full scale human hearts, the professor notes, require the same basic technology, although the process of scaling up is vastly complicated. “We’re now working on the pacemaker cells, the atrial cells, the ventricular cells,” Dvir says. “But it looks good. I believe this is the future.”

How 3D bioprinting works

The ability to 3D print human organs is an astounding notion. Nearly 106,000 Americans are currently on waiting lists for organ donations, and 17 die each day while waiting, according to the federal Health Resources and Services Administration. A 3D printing process that uses the patient’s own cells to grow organs would not only potentially curb that waiting list, but dramatically reduce the chances of organ rejection and likely eliminate the need for harmful life-long immunosuppressive medication.

“The ability to place different cell types in precise locations to build up a complex tissue, and the capability of integrating blood vessels that can deliver the necessary oxygen and nutrients to keep cells alive, are two (3D) techniques that are revolutionizing tissue engineering,” says Mark Skylar-Scott, an assistant professor in the Stanford University department of bioengineering. “The field has moved very quickly over the past two decades, from printed bladders to now highly cellular tissues with vessels that can be connected to a pump—and complex 3D models that resemble heart components with integrated heart cells.”

In 3D bioprinting, the name of the game is cells. The process begins by generating the cells that researchers want to bioprint, which are then instructed to become organ specific cell types. The cells are then rendered into a printable living ink, or bioink, that involves mixing them with materials like gelatin or alginate to give them a toothpaste-like consistency. Stanford’s lab is studying how stem cells might naturally form such a consistency if crammed together at high density, which could lead to 3D printed organs made strictly from a patient’s own cells.

The bioink is loaded into syringes and squeezed out of a nozzle “like icing on a cake,” Skylar-Scott says. This is the actual 3D bioprinting process, and it typically involves laying down different cell types, each loaded into a different nozzle. (Dvir says the mini-heart took about four hours to print.) Once it is finished, the tissue is sometimes connected to a pump that drives oxygen and nutrients through it. Given time, the tissue develops on its own and increases in both maturity and function.

That general process, though dramatically oversimplified here, is what led to the production of the external part of the ear that Arturo Bonilla implanted in his patient in Texas. In most previous microtia surgeries, Bonilla would have carved a new ear out of cartilage taken from the patient’s ribs. Instead, a small biopsy was performed on the patient’s other ear and cartilage cells taken from the biopsy were grown into billions of cells, which were 3D-printed into the new implant.

“As with any study, there will likely be iterations in future patients in order to try to improve this technique,” Bonilla says. “We are unsure when this will be the mainstay treatment, but the future is very exciting.”

Advantages of 3D printing

Wake Forest scientists have been lab growing organs and tissues for years. They’ve used 3D printing to create in the laboratory essentially a mini-kidney and a mini-liver. The next challenge: larger, solid structures that more fully mimic organ function. “We are far from achieving this goal at organ scale,” says Jennifer Lewis, Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering, at Harvard University.

“We’ve been able to print flat structures like skin, tubular structures like blood vessels or hollow, non-tubular organs like a bladder,” says Anthony Atala, founding director of the Wake Forest Institute. The larger solid organs are different, Atala says, “because of the challenge with the vascularity or the nutrition. There’s so many cells per centimeter.”

In some ways with cell production, it’s a matter of quality. Scientists have been able to create a heart cell from stem cells, but not one that beats as strongly as your heart cells do. The same is true for liver cells (metabolism) and kidney cells (filtrate uptake). “In some ways,” Skyler-Scott says, “the 3D bioprinting field is waiting on the basic biologists to make their major breakthroughs.”

There’s also the issue of quantity. The creation of a heart would require “billions of cells – and you need different cells, even different cardiac cells,” says Tal Dvir. To make enough cells for a single organ, a facility would need a 10-liter stirred vat that might cost $5,000 per day to feed, for months on end according to Skyler-Scott. And the ultimate goal is thousands of organs a month, not one.

Beyond all that, there are the questions of how the tissue integrates into the body and how it is supported by the body, including complex networks of blood vessels, nerves and multiple cell types, says Dan Cohen, CEO and co-founder of 3D Bio Therapeutics. “It’s not to say it can’t be done,” says Cohen, who began working in the field of bioprinting 20 years ago, when it didn’t have a formal name. “I have a lot of hope for bioprinting and regenerative medicine more broadly.”

Even in the short term, progress is well marked. Researchers at Harvard, Lewis says, generated cardiac cells from human pluripotent stem cells, then seeded them on a bioengineered chip with integrated sensors that can track the beating tissue. This 3D-printed-heart-on-a-chip can be used to test various cardiac drugs for potentially toxic side effects and may alleviate the need for animal testing.(A similar ALS-on-a-chip technology is being used to screen for drug candidates and to better understand the underlying mechanisms of that disease.)

“The 3D printer gives you several advantages,” says Wake Forest’s Atala. “The first is scale-up, because instead of making these (tissues and organs) by hand one at a time, you can automate the printer to do it. The second thing is precision. We can more precisely locate the cells where they’re needed.”

There’s also the notion of lower overall cost, as 3D printing allows for that increased scale. There is what Atala calls “reproducibility,” a method of producing the same structure again and again. And in terms of organ transplant, a new organ made of a patient’s own cells makes rejection far less likely.

Most researchers put the idea of full-sized 3D-printed organ transplantation in humans at somewhere between 20 and 30 years away. “Eventually, looking ahead, we’ll not need donor hearts. We’ll not need livers,” Dvir says. “This is my opinion, and I’m optimistic, but I think that in less than 20 years we will have printed organs inside us.” That is science at work, not science fiction.