现代主义大师——贝聿铭

|

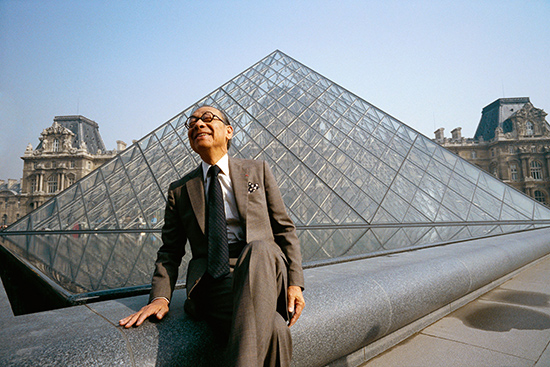

上周,美籍华人建筑师贝聿铭在纽约曼哈顿的家中去世,享年102岁。贝聿铭是上世纪最著名的建筑师之一。令他备受赞誉的美国国家艺术馆东楼、法国卢浮宫玻璃金字塔等作品,都是在建筑史上有一席之地的杰作。 对我这个土生土长的丹佛人来说,他的作品给我留下印象最深的,是市中心的一座具有国际风格的建筑,它由4栋楼组成,高22层,长约一个街区。这座建筑于1960年完工,虽然它在贝聿铭的作品中并不出名,但它的设计是非常超前的,它是一个集酒店(起初是希尔顿酒店,现在已经换成了喜来登酒店)、停车场、公共空间和百货商店集一身的商业综合体。这种地产项目现在已经司空见惯了,但在 60年前却是一种革命性的设计。因此,该项目毫无悬念地获得了1961年美国建筑师协会的国家荣誉奖。(遗憾的是,该建筑的一个亭子后来被拆除了,百货商店也重新装修了,随着时间的推移,由于人为或自然损毁,酒店内部的很多细节也没能保存下来。但它时至今日仍然是一座很美的建筑。)几年后,贝聿铭又在附近完成了另一座宏伟建筑——国家大气研究中心,它坐落在科罗拉多州博尔德的一片山坡上。贝聿铭的公司还设计了丹佛的16街商场,这家商场于1982年开业,成为了市中心的新地标。 贝聿铭不仅懂得设计能够打动人的建筑和空间,也懂得设计与文化和社会相和谐的建筑。他的设计兼具传统和前卫风格,能够紧抓时代潮流,这也意味着他敢于突破边界。同时,贝聿铭的设计又十分注重对自然环境的尊重和保护。贝聿铭从来不是一个追求时尚和潮流的人,他的作品关注的是体积与重量、结构与材料,他对简单的几何图案运用得炉火纯青。 贝聿铭既是一位富有远见的设计师,也是一名精明的商人,在政商两界都游刃有余。随着他的设计业务大获成功,他的公司也变得十分富有和强大(贝聿铭于1955年创办了自己的贝聿铭建筑事务所,1966年将公司的英文名从I.M. Pei & Associates变更为I.M. Pei & Partners,1989年又将其更名为贝聿铭考伯弗里德事务所(Pei Cobb Freed & Partners)。建筑评论家保罗·戈德伯格本周在《纽约时报》撰文称,贝聿铭是“少数几个对房地产开发商、企业大佬和艺术馆的董事会(当然,第三种人通常由前两种人组成)都同样有吸引力的建筑师之一。”这就是贝聿铭的世界。 可以说,贝聿铭的成功与他的家庭出身有很大关系。他的父亲叶祖贻是中国最大的银行家之一。他从小就在广州(也是他出生的地方)、香港、上海等地受到了上流教育。他的家庭文化根植于中国传统,但也接受了西方的文化和理念。 贝聿铭的商业头脑,很大程度上是在20世纪40年代,也就是他职业生涯的早期形成的。他在哈佛设计学院获得硕士学位后,与他曾经的老师、包豪斯学派的创始人沃特·格罗皮乌斯并肩执教两年。(贝律铭的本科是在麻省理工学院完成的,期间曾经短暂在宾西法尼亚大学就读,后来转出了该校。)最终,大胆的纽约开发商威廉·泽肯多夫聘请了贝聿铭,30岁出头的贝聿铭开始进入建筑师生涯的上升期,很快实现了名利双收。泽肯多夫在政界和商界的关系为贝聿铭提供了难得的跳板,在接下来的几十年里,贝聿铭先后完成了克利奥罗杰斯纪念图书馆(1963年,印第安那州哥伦布市)、约翰肯尼迪总统图书馆(1979年,波士顿)和中银大厦(1990年,香港)等一系列备受赞誉的作品。 很少有设计师的作品可以用“永恒”二字来形容。在评价建筑作品时,我一般也会避免这个字眼。但贝聿铭的多数作品用“永恒”来评价并不为过。他天才而又直白地使用各种造型和形状,构造出宏大而又简洁的建筑,从而展现出强烈而清晰的设计语言。他是一位真正的、纯粹的、杰出的现代主义艺术家。如果你在一个地方看到了贝聿铭设计的建筑,你会清楚地记得它的风格。贝聿铭的很多作品现在也已经上了年纪,但它们仍然能够刺激人的感官和情绪。贝聿铭是一位目光长远的建筑师,他设计的建筑,也能够经受住时间的考验。 当然,贝聿铭也并非事事一帆风顺。比如波士顿的约翰汉考克大厦就因为施工混乱、财务困难和多次延期,成了众所周知的一个失败项目。纽约的雅各布贾维斯会议中心项目也由于暴露了诸多问题而饱受批评。不过瑕不掩瑜,贝聿铭对建筑界乃至全世界的影响还将继续存在下去。他一直以来的超前思想和远见卓识就是他终极的力量。(财富中文网) 译者:朴成奎 |

I.M. Pei, who died last week in his Manhattan home at age 102, was among the most celebrated architects of the last century, widely praised for his high-profile designs of the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the glass pyramid entrance at the Louvre in Paris. For me, a Denver native, his standout is a 22-story, block-long, four-building concrete International Style wonder situated in the city’s downtown. Though it is perhaps one of the lesser-known projects in the Pei oeuvre, the multi-purpose Mile High Center, completed in 1960, was ahead of its time, combining a hotel (opened as a Hilton and now a Sheraton), parking, public space, and a department store. This kind of development may be the norm now, but six decades ago it was revolutionary. Perhaps not surprisingly, the project was the winner of the American Institute of Architects’ National Honor Award in 1961. (Sadly, a pavilion on the site was later demolished, the department store was garishly updated, and the hotel now lacks many of its original interior details, which were gutted or destroyed though changes over time. Still, it is a beautiful building to behold.) Several years later, Pei would complete another exceptional structure nearby, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, subtly nestled into the rocky foothills of Boulder, Colo. His firm would also design Denver’s 16th Street Mall, which opened in 1982 and helped establish a new nexus for downtown. Pei understood not just how to make buildings and spaces that moved people, literally and figuratively, but how to construct culturally and socially attuned architecture. At once traditional and progressive, his work often captured the zeitgeist, which also meant it pushed boundaries. Yet it typically showed reserve and respect for nature and its surroundings, too. Pei was never one to chase styles or trends. His buildings were about mass and weight, heft and material. His structures were celebrations of simple geometric patterns. Pei was both a visionary designer and a savvy businessman who had the shrewd ability to move within the wealthy and powerful with ease. And with the massive success of his architectural operation, I.M. Pei & Associates, which he set up in 1955—it later became I.M. Pei & Partners in 1966, and then Pei Cobb Freed & Partners in 1989—he too became wealthy and powerful. Writing this week in the New York Times, architecture critic Paul Goldberger noted that Pei “was one of the few architects who were equally attractive to real estate developers, corporate chieftains and art museum boards (the third group, of course, often made up of members of the first two).” This was Pei’s world. In a way, he born into it—his father, Tsuyee Pei, was one of China’s leading bankers. His upper-class upbringing included moves from Guangzhou, where he was born, to Hong Kong and later Shanghai. His family’s culture was rooted in Chinese tradition but included access to Western ideas and ideals. Much of Pei’s business acumen was shaped early on in his career, in the late 1940s. After receiving his master’s from the Graduate School of Design at Harvard, he taught for two years alongside Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus School, whom he had also studied under. (Pei attended M.I.T. for his undergraduate studies and also did a stint at the University of Pennsylvania, which he transferred out of.) Eventually hired by the bold and brash New York developer William Zeckendorf, Pei began his architectural ascent in his early 30s, quickly entering a rarefied orbit of influence and money. Zeckendorf’s access to the wealthy and powerful provided a rare springboard for the young architect, who over the next few decades would go on to design lauded projects such as the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library in Columbus, Indiana (1963), Boston’s John F. Kennedy Presidential Library (1979), and the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong (1990). There aren’t many designers whose collective body of work could be called “timeless.” Or anyway, I certainly try to avoid that word when describing architecture. But with Pei, for the most part, it’s apt. His ingenious if straightforward uses of shapes and forms often led to grand, clean-lined buildings that showcased his strong and clear architectural voice. He was a true, pure, masterful modernist. You remember a Pei building when you visit one. The bulk of them have aged well, many of them for exactly that—their bulk. They evoke feeling and emotion. He was an architect who took the long view and as such made buildings that could stand the test of time. Not everything Pei did was a smooth success, of course—Boston’s John Hancock Tower, with its construction snafus, financial troubles, and various delays, was a notable public failure, and New York’s Jacob K. Javits Convention Center has had more than its fair share issues and reasonable critiques, too. But there’s no doubt that Pei’s impact on the field of architecture, and on the world at large, has been—and will continue to be—long-lasting. His consistent, forward-thinking vision was his ultimate power. |