本文是《财富》杂志气候变化突破方案系列报道的一部分,客座编辑为比尔·盖茨。

动笔十多年后,比尔·盖茨的新书《如何避免气候灾难:我们拥有的解决方案和我们需要的突破》终于面世。“如何避免”那部分做起来并不容易,但盖茨计划的明确性和紧迫性,可能会让数百万读者迅速积极响应起来。

《财富》杂志希望进一步深入挖掘,探索盖茨和其他人提出的挑战。为此,我们邀请这位著名的慈善家担任2月16日当天《财富》杂志的“客座编辑”。

本书出版之前,《财富》杂志主编黎克腾,跟微软联合创始人也是投资人盖茨坐下长谈,讨论如何才能防止气候变化恶化,新能源“奇迹”传递错误信息,以及当前盖茨向哪些领域大举投资。至于讨论中谈到了他对人造肉汉堡(以及其他一些著名投资人的少量“投资目标”)的浓厚兴趣,则是意外收获。

为了简洁及表述清晰,对话经过编辑。

比尔,你刚刚写了避免“气候灾难”的书,然而现在地球上大多数人都在关注另一场灾难——新冠病毒。你担不担心读者可能没准备好同时面对两种威胁?

先说说我为什么要写这本书。2008年,在我离开微软的几年前,在微软工作的一些朋友说:“比尔,你应该关注气候变化问题。”

我读到瓦茨拉夫·斯米尔的书,对钢铁、水泥、电力等物质经济产生了浓厚的兴趣。他让我意识到,人们对轻易获取各种资源感觉理所当然。

比如电力非常可靠又廉价,斯米尔在书中谈到电力普及方面各种令人惊叹的工作。当然,这些工作也是导致温室气体排放和加剧气候变化的因素。所以我开始思考如何改变一切。我在想:“真能实现吗?”

当然,基金会在贫穷国家已经在做各种工作,经济欠发达国家的建筑通常是用废旧金属建造。没有输电线。用水方面,一些地区的屋顶上装有小型水箱,因为当地没有给水系统,即便有也极其不可靠。

后来,朋友介绍我认识了肯·卡尔德拉教授(卡内基科学研究所)和大卫·基思教授(目前在哈佛大学执教)。我们一年开六次会。他们也会介绍其他专家参加,我们选择某个话题,比如储存能量、电动汽车或炼钢,提前阅读大量材料,然后讨论半天。我对相关话题非常感兴趣。

我的理解框架其实不少,2010年我在TED发表了演讲(题目叫“从零开始创新”),一共讲了三场。其中一场关于政府预算问题在哪,我保证总有一天这会被当成预言;2015年的演讲关于疫病,可能是到现在浏览量最高的一场(编者按:该场有先见之明的TED演讲标题是“下一次大爆发?我们还没有准备好。”目前浏览量已经达到3900万次。);关于气候的那场并不长。我想想,大概15分钟?——可以找来看看。

那场演讲的目的是:“困难太大,需要创新——很多创新。”尽管我现在比十年前知道得更多,但那仍然是我的基本认识框架,也是新书的框架。

但就像现在一样,十年前你在TED上发表关于气候变化的演讲时,全世界也被另一场全球危机分散了注意力。

不幸的是,2010年左右那段时间里,也就是金融危机之后,(应对)气候变化的能源消耗大幅下降。然后随着经济开始复苏,兴趣稍微上升。

对我来说,之后一个重大里程碑是2015年巴黎气候谈判之前一年,当时我对大家说:“为什么人们开这些会议,却不讨论研发预算和刺激创新的想法?”

大概结构是:“我们以国家身份来谈谈近期进展。”最近在风能、太阳能发电,以及电动汽车应用方面有些进展。并不是说这些事情很容易,但这都是最容易做到减排的手段。

所以当你说:“五年后或者十年后能够做什么?”人们并不会答:“我正用全新的方式炼铁。”因为各国炼铁方式差别不大。钢铁在全球都是具有竞争力的行业。因此,温室气体排放70%以上的来源从未出现在“让我们讨论下短期减排”的讨论中。奇怪的是,真正难推动的领域几乎没人讨论过,占排放70%的钢铁、水泥或航空就是很好的例子。

但到了2015年,在COP21(跟当年巴黎联合国气候变化大会同时举办的可持续创新论坛)上,这问题被提了出来。

法国组织者想做一些不同的事情,他们希望(印度总理纳伦德拉)莫迪能来。莫迪并不想参会,然后被追问“短期减排多少?”因为印度的电力需求是现在的五倍,才可以让大部分人口维持基本的生活方式。所以他不会出席。

但是,COP21的附带结果也就是所谓的使命创新,不仅关注增加能源研发预算,还要确保有私营部门投资者愿意承担风险,将有希望的创意转化为公司,前提是研发实验室将创意变为现实。

当时,Kleiner Perkins的约翰•多尔或维诺德•科斯拉的风投基金做了大量绿色投资,业绩并不好。Kleiner Perkins赌的是菲斯克(汽车)而不是特斯拉。很多太阳能电池板方面的(投资)并不顺利。所以我承诺筹钱向该领域投资。

后来就成立了突破能源风投基金,隶属于我旗下主要关注气候变化的机构。公司覆盖几个不同的领域,包括专注政策解决方案的部门。不过当前主要是从事风投。

我们筹集了刚好10亿多美元,现在投资了50家公司,进展很顺利。我们也找了其他人投资。

本书出版的时候(2月16日),我们称之为BEV2的风投基金已经融到数十亿美元,将继续投50家公司,其中大部分都会失败。即便是成功也比典型的软件公司更难,因为需要投入大量资金,还需要产业合作关系。所以这是完全不同的投资方式,我的目标是帮助扩大创新规模。

但是,就在你扩大投资规模还召集其他投资者和决策者关注能源领域的激进创新时,赶上了新冠疫情。你似乎把注意力和慈善事业放在寻找新冠治疗方法和疫苗上,去年9月你接受《财富》杂志采访时谈到过。

这应该夸一夸这一代的人们,即便当前身处疫情中,大家也还是真正关心气候危机的。

这次不像金融危机(2007年-2008年)期间,当时人们说,“现在情况很艰难,没有工夫管气候变化。”即便到2010年,如果对公众民意调查,也会发现人们对气候的兴趣已经下降。

而在接下来十年里,关注又逐渐增加,遭遇疫情时我还在想:“会出现什么情况?”实际上,疫情期间人们对气候变化的关注有所上升,这有点奇怪。

看看拜登总统挑选的专家,也是差不多情况,这届政府里,有很多气候问题专家。总统正关注着几个互相叠加的危机,疫情和气候变化重要性相当,这点相当让人赞叹。

而且总统初选和大选期间,候选人遇到的气候问题数量比以往都要多。再看看欧洲的复苏计划,资本投资也极其倾向气候变化领域。超过三分之一的资金都与此有关。

所以我感觉很幸运,在某种程度上年轻人提升了话题的重要性。我年轻的时候都没做到。当时我都没上街游行。

我的观点是,“既然你们如此关心,而且能够理想主义地说:‘让我们尽一切努力在2050年之前实现零排放’——就应该制定相应的计划,根据计划逆推,然后说:‘钢铁、水泥和航空要怎么做?’”

不希望人们想:“哦,我们只想确保多装几个太阳能电池板。”然后10年过去,排放并没有什么变化。

所以除非计划得当,否则最后只会引发很多愤世嫉俗和失望。

所以你决定把计划写成书。

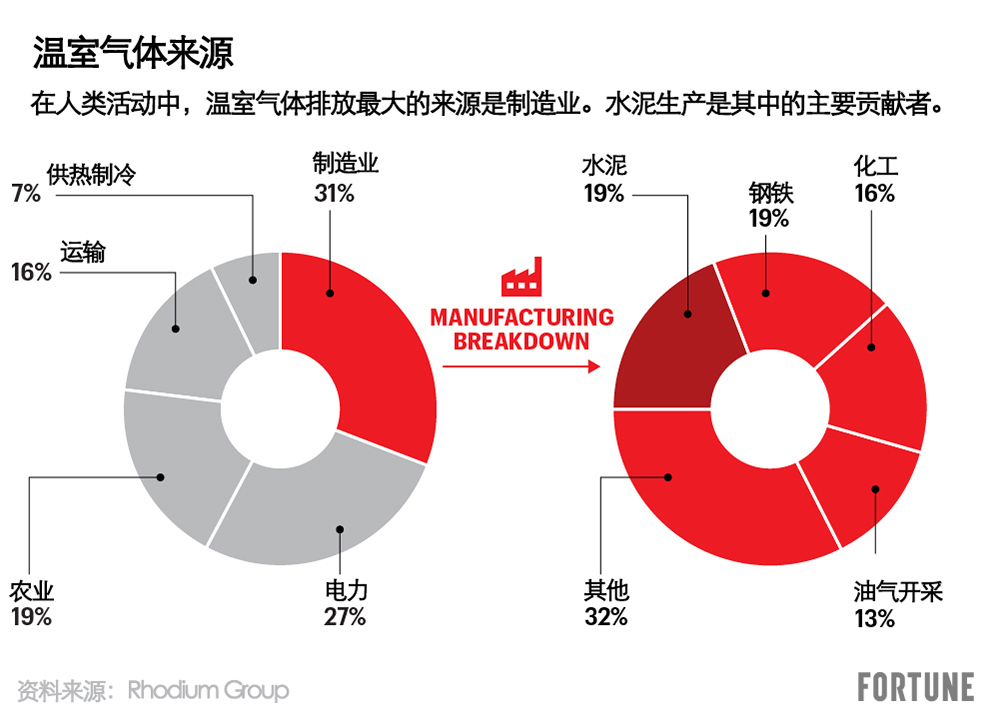

是的,新书主要说的是计划。书中没具体解释为什么气候变化有害,但还是用一章的篇幅大概讲了讲,还有一章关于适应的。但书中大部分内容主要还是类似于:“温室气体排放达510亿吨,以下列举出排放的领域。”看看各领域的情况,然后说:“如果想实现零排放,达到同样产量成本的情况下,要贵多少?”

这就是我说的绿色溢价指标。我们能够讨论的是:“当今水泥的绿色溢价是多少?哪家公司的技术能够实现减半?有没有可能降到零?”

将绿色溢价降到零是很神奇的,未来十年电动汽车将能实现这个目标。也就是说,不需要政府资助创新,也不需要个人资助。只要量达到一定程度,产品变得便宜,充电站也变得普及,政客就可以参与。

到时政客就能够说,2035年、2040年之前禁止燃油车,公众不会震惊地问:“什么?!”

如果绿色溢价降到接近零,相关政策的实行就成为可能,不过在大量碳排放的地区也要采取同样措施。有些领域,比如钢铁或水泥生产实施起来都很困难。不管怎样,这都是最基本的。

我非常喜欢这本书的一点是,读者可以体验学习气候科学的过程。举例来说,你对汽油比苏打水便宜感到惊奇,或者解释为什么某些气体吸收或反射太阳辐射取决于原子组成时,感觉好像你正在高兴地跟读者分享发现。在写书的过程中,你有没有意识到要分享个人发现之旅?

对我来说,所有东西都很有趣。

当你在其他某些地方读到相关内容时,对内容的解释经常并不清晰,比方说,你会读到文章说:“减排力度相当于10000户或40000辆汽车。”

你得想:“我得费劲理解数字,总数是多少,然后算这些数字占多少?”

我想把数字简化,如果有人谈到10000户或40000辆汽车碳减排时,我就能够回答这个问题:“占总碳排放量的百分比是多少?”

大多数人读到相关文章时会说:“这些都只是胡言乱语。”当一开始努力理解时,能量单位都非常大,容易让人感觉混乱。对我来说,能够利用某些熟悉的事物去理解比较有吸引力。

必须承认,这本书非常感谢肯·卡尔德拉和大卫·基思,他们向我传授了很多知识,还介绍了很多人。

还有像(微软前首席技术官)内森·米尔沃德和(多产发明家)洛厄尔·伍德等人,每当我对物理或化学方面有疑惑时,就给他们写邮件。当然还有瓦茨拉夫·斯米尔,他写了很多书,对诸如1800年工业经济的概况和之后的重大突破的着迷,为我提供了灵感。

我很喜欢研究这些。其实很简单。跟大多数领域一样,就这么几个概念,但必须真正了解它们。

比如能量速率、能源数量,以及储存时间。

对能源来说,这些相当于“能不能想用的时候就用?”斯米尔做了直观展示,“一座城市耗能量多少,或者一个家庭耗能量多少?”这样脑中就能理解各种数字和常识。

为了理解,我带儿子去煤矿工厂,还去了水泥厂和造纸厂实地参观。因为我们只懂软件,在化学实验方面实在不擅长。

以前我想的是:“只算化学方程式就好,别用试管实际操作。我可能造成爆炸。”

成长过程中,我从没有造过小火车或飞机之类的物品。所以我一直觉得:“上帝,实体的东西才是真的。”

我是说,得有人真去建造机器和工厂。

不管怎样,学习很有趣。如果告诉别人我花了多少时间或者读了多少书,就得小心点,因为听起来像是吹牛什么的。但我最大的优点就是喜欢当学生。

我很喜欢的说法是,只要了解得足够多,实际上什么事情都很简单。我有足够的信心,还有很聪明的朋友,他们会帮我达到目标,我可以说:“我要学习,最终达到一切都能够解释通的程度。”

在书中的某些部分,你似乎在凝视未来。去年秋天我读到第一版书稿中,你提到“美国退出2015年巴黎协议”,还说“之后美国总统拜登会将其逆转”。你早在美国总统大选前就能够预测到,真令人惊讶。

书中的大部分内容实际上是在10个月前就完成了的。我当时考虑了很久,要不要出版。

刚开始问题是,如果特朗普连任,显然会影响美国按照书中呼吁行事的能力。这本书主要关于创新,美国控制着当今世界50%以上的创新能力,创新会发生在大学里、国家实验室里,还有风险投资当中。如果不让美国推动创新,那么全世界创新都会停滞。因为在美国,创新不仅仅为了本国公民,也为了其他人。

如果我们可以廉价制造清洁(无碳)水泥,30年后当发展中国家为人民建造住房时也会选择清洁水泥。

所以当我写作时,最后几章变得非常复杂,我不得不琢磨措辞,“如果民主党候选人当选……”等等。

还有疫情来袭,我想,“哦,人们注意力可能有点分散。”

所以在大选后,我决定对书做点修订,也许增加一些技术进展。大选后我对书完整检查了一遍,又加了些内容。

从第一章到第九章,几乎没有重大修订。但到了第10章至第12章,谈及政府政策等相关问题时,我做了相当多修改。即使民主党控制了白宫和国会、参议院几乎平分秋色,而且美国已经陷入赤字,我们也必须拿出不需要大量资源的计划。

这是可行的,我相当乐观。

其中涉及的政治太复杂。在第11章路线图中,你提出了激励和抑制或惩罚政策措施,也就是胡萝卜和大棒。但过去我们看到,棍子更难到位。

以《平价医疗法案》为例,行政部门和国会两院中民主党占多数,仅仅是个人授权和相关处罚的概念就已经导致立法内战,而且到如今仍在持续。

我读到书中关于碳价格设定部分,实际上是“碳税”,税率高到能够抵消绿色溢价,我想知道你对近期实现的把握有多大?正如你写到:“为碳排放定价,是消除绿色溢价能做的关键事项之一。”

如果没有创新,即便碳捕获可以降到比方每吨100美元,仍然要面临巨大挑战,因为每年碳排放量有510亿吨。在世界上某个地方必须找到每年5万亿美元的支出,占世界经济5%以上。这是不可能的,没机会。

当然,从政治上征收任何形式的碳税都非常困难。法国试图提高柴油价格时,人们大喊:“嘿,不能这么做!”类似努力不可避免地被减弱,因为实施起来的收获与人们的感受并不成比例。

可以尝试进行弥补,但在法国的例子中,住在城市之外不得不开车赶路的人,觉得住在城市的精英忽视了自己,这也是各个富裕国家普遍存在的政治现象。最终法国还是废除了柴油税。

现在公众不太愿意掏钱避免负面影响,毕竟这些负面影响大多在遥远的未来。我是说,确实有一些有关天气的负面现象已经显露,比如森林火灾,还有非常炎热的日子。

很高兴人们已经注意到,如果目前不采取行动,如今的负面影响将无法与2080年和2100年的境遇相比,对生活在赤道附近的人来说更是如此。到2100年,夏天在印度户外活动将难以忍受。户外工作根本不可能,毕竟身体的排汗量是有限的。

书中接近结尾的地方,你总结实现零排放的计划时谈到“加速创新需求”。这一概念似乎对成功非常关键,而且似乎跟你在慈善事业中做的很多工作也有所不同。你跟梅琳达创立的基金会经常资助创新投资的公司。但在一些根本不存在市场的地方开创建立需求侧,是另一种挑战。

例如在制药行业,制药巨头通过大量生物技术初创公司为创新提供市场,跟有希望治疗某种适应症的实验候选药物竞争。气候方面是否也有类似模式,即能源巨头为能源初创企业在零排放方面的进展提供现成市场?还是像国防工业创新一样,“市场”必须由政府提供?

能源方面难得多。相比之下,软件反而最简单。医学的难度介于中间。与气候有关的事情最困难。

软件方面,总有一些客户不喜欢现有的软件,认为应该更简单、更便宜,或者在某些方面功能更多。只要能从垄断巨头那里抢来一小块市场,就可以服务某些客户,因为你能够更好地满足需求。软件创新者面前有现成的市场。

医药也一样。看看各种各样的疾病,也许新产品是口服而不是注射,或者能够减少一些副作用。或者,希望每隔一段时间找到全新的方法治疗不治之症。但这一行业同时也要面临各种监管、检查和副作用等问题。

气候变化方面最困难的是,制造清洁钢铁除了能够保护地球之外,并没有额外益处。如果仅仅是跟传统上公认的工艺略有不同,买家很可能发出疑问:“耐用吗,会变脆吗,会生锈吗?”

人们对任何变化都抱着怀疑态度。因为钢铁非常可靠,水泥也一样。有个公式可以精确计算强度,测试本身不是为了测试特性,只是测试是否遵循了公式。因此,市场中并没有专门一块愿意为清洁钢铁或水泥支付更高价格的。

现在太阳能电池板的情况是,卫星需要能源,太阳能电池板是唯一的方法。哪怕不经济,德国和日本也买了。量不大,但足够启动学习曲线。然后包括美国在内其他国家实施税收抵免,学习曲线逐渐扩大。

我们已经看到学习曲线模式在风能和锂离子电池上的应用,这是算是奇迹。

可悲的是,大多数人认为,“电池做得够汽车用,就可以做得能够让整个电网都用,我们要在电网创造另一个奇迹。”但他们没有意识到,很多希望创造奇迹的尝试,比如燃料电池或氢动力汽车都还没有成功。

举个例子,在裂变动力核反应堆方面,创新还有其他难点。成本和安全问题引发的担忧非常大,除非用全新设计重建反应堆,在经济性和安全性上彻底革新,否则前路只会是死胡同。这就是我在(核能公司)TerraPower(盖茨担任董事会主席)努力做的事情。

如果把过往的成功投射到这些领域,最后可能认为事情比实际情况简单得多。你提的问题非常好,因为书中描述整体战略的一部分,就是为清洁钢材找买家。

假设现在绿色溢价是每吨100美元。有人创办一家每吨溢价仅50美元的清洁钢铁公司,你会对那个人说:“干得好!”但事实上市场规模为零,因为每吨多出50美元,只意味着成本更高。

现在我们要做的是努力让资金更充裕的公司,比如科技巨头同意每当建造新大楼,就要使用20%的清洁钢材。回报是可以对外宣称:“大楼用了20%的清洁钢材。”

所以我们得创造需求侧。我热爱创新的供给端,要去找教授,找有疯狂创意的人。所以突破能源投资公司有很多类似的项目。

基金投的50家公司中,有一家发现向地下注水并在地下岩层之间储存可长期储存能量。要注水就需要能源,如果电力充足就能够做到。然后如果想使用能量就打开井,放出高压水为涡轮机提供动力。

但估计该创意无法实现。公司叫Quidnet,估计名字是为了致敬哈利·波特之类的。不管怎样,资助此人就代表了我们的倾向。这就是供给侧创新。

需求方同样必要,可以用人造肉公司为例。令人惊讶的是,人造肉市场由消费者的选择驱动。当汉堡王开始提供人造肉汉堡时,需求量非常高,这是好事。

然而在钢铁和水泥行业,清洁技术实在晦涩难懂,要创造需求就困难得多。航空燃料方面,清洁燃料的额外成本,意味着机票要高出25%。鸡尾酒会上人们可能会说,愿意多付25%。但我怀疑如果真到了紧要关头,支付绿色溢价的消费者能否负担总体成本。

因此,为钢铁水泥产业打造创新市场,比为软件和医疗行业都困难得多。这可能是突破能源投资设定了20年有效期和不同的激励机制的原因。投资者都知道,大多数公司的成功几率很小。

你有没有想过向公众投资者开放基金或类似基金,还有让人们购买份额以协助开创需求?

我们还没有想到这一步,但我认为如果企业能够按照每吨价格估算清楚碳排放量以及成本,就可以劝说企业写支票解决问题。

原则上来说,这些支票能够资助基金竞拍,可以这么说:“谁能以最低价格提供清洁钢铁?谁能供应清洁水泥?”

所以我比较认同,不管是对自己的碳足迹感到内疚的个人还是企业,尤其是利润丰厚的企业,都可以认购基金,就像航天工业支持太阳能电池板一样。换句话说就是创造需求。

这是我想组织的事。某种程度上人们会说,“我也为突破能源采购做出了贡献”,并为此自豪。

你可以像沃伦•巴菲特在伯克希尔•哈撒韦那样,为富裕企业创建A股,为其他人创建B股。

是的,区分白金和黄金。

如果说,能从观察你长期得慈善事业中领悟到什么,应该就是你似乎一直是围绕着人们所说的先行者做事。如果你可以改造X,就能够减少X带来的不良后果。

因此,当你和梅琳达创立比尔及梅琳达盖茨基金会时,合乎逻辑的第一步是投资全球卫生,努力消除疟疾、腹泻病、不受重视的热带疾病、小儿麻痹症等。当然,减少每年生病和死亡的儿童人数本身不仅是好事,理论上也会带来一系列好效果。首先,确保更多健康又有生产力的公民振兴发展中国家的经济,就可以减少地方性贫困。

所以如果你能够解决某件事,就能对下游一些事产生积极影响。基金会在教育方面的投资也有类似的乘数效应,尤其是年轻女性和女孩的教育方面。正如梅琳达所说,5岁以下儿童死亡率的首要指标是母亲的教育状况。如果能解决这个问题,就可以帮助一代又一代人脱贫。

其他主要投资上也遵循同样思路:例如改善卫生条件可以减少霍乱、伤寒、腹泻病、痢疾等等。

现在你大力转向气候变化领域,可以说这可能是一系列问题中的终极“先行者”,如果不加以阻止更是如此:要么解决气候变化问题,要么迎接世界末日。

如果推理没问题,多年来你和梅琳达关注的各种事务中,气候变化的地位是不是越来越重要?在各种迫切需求上,你怎么分配时间、注意力和资金?

在基础领域,也就是全球健康问题上,每一美元的影响都是巨大的。我们拯救每条生命的代价不到1000美元。之后可能会出现市场失灵,因为发达国家并不存在疟疾,所以并没有指导创新者开发疟疾药物和疫苗的市场信号,也没有消除疟疾的总体战略。疟疾流行的贫穷国家却没有消除疟疾的资源。

我投出第一笔3000万美元抗击疟疾时,成了疟疾领域最大的资助者。这可以说是一种悲哀,这也许是显著推动变革的机会。

从事气候变化的人们都谈论碳捕获。我是各家公司最大的出资人,大概投了数千万美元,其中包括Climeworks、Carbon Engineering和Global Thermostat等。碳捕获领域有四五家公司。幸运的是,还会有更多,因为它们有不同的方式。

每当我发现某些投资,如果成功的话,每一美元的社会影响大概能有千倍回报,我感觉就像风险资本家投了早期谷歌或类似公司一样。这很吸引我。

随着时间推移,看到潜在的创新获得成功,我很开心。我喜欢和可以同样看得远并愿意保持耐心的人们一起工作。甚至某些情况下,我们还押注多种途径,虽然明知其中一些会失败,例如预防或治疗艾滋病。花很多钱投入到不同方法中,即使最后只有一种方法奏效,那也是一种奇迹。

关键是创新思维。有些事,比如改善美国的教育,如果采取宽泛的指标,如“美国学生在数学、阅读和写作表现如何?”或者“有多少孩子从大学辍学?”我们对全球卫生工作的影响还没有这么大。

我们仍然相信我们可以产生影响,也在加倍努力。在疫情期间,更多孩子真正拥有笔记本电脑并连接互联网的想法得到了极大的推动,真正建立了非常不同的新一代课程。

即使目前影响几乎很难察觉的领域,也还是存在希望。事先不会知道能发挥什么作用。解决问题的大多数努力都比想象中困难。

有些事,比如我投钱给Beyond Meat和Impossible Foods时,从一开始我就说:“改造肉”就像制造零碳钢和水泥一样困难。现在虽然还没有解决,但已经有了出路。情况跟电动汽车差不多,就是成本降低和质量提高,合成人造肉方面的具体表现是,出现各种生产方式,绿色溢价将为零。生产速度真的快到让我很吃惊。

书中让我吃惊是你对能量储存自然极限的信念。有些人仍然把希望放在近乎无限大的蓄电池上,或者至少是容量超大的蓄电池,如此一来可以让太阳能、风能等途径获取的电力更容易储存。

在我看来,这也是书中让人难过的一块。储存能量方面不能应用摩尔定律的观点让人很难接受。

是啊,摩尔定律能够持续这么久已经很令人兴奋。软件和数字技术让人们认为总是有可能出现奇迹,然而实际上进步更像百年来汽油里程的变化。如果爱迪生复生看到我们的电池,他会说:“哇,这些电池比我发明的铅酸电池好四倍。干得好。”电池百年创新不过如此。

人们混淆了电动汽车电池和行驶里程的区别,里程再扩大两倍就非常理想,而电网储存的电池目的是夏天收集太阳能,然后冬天使用。这个例子中,一整套电池整体只能够发挥一次作用,即每年可以使用一次电力。

成本和规模化非常困难,我们还有20倍的差距。我在电池公司亏损的钱比其他企业都多。现在我在五家电池公司工作,有几家直接参与,也有几家是通过BEV(突破能源投资公司)。

解决电网问题只有三种方法:一是储存方面出现奇迹,二是核裂变,三是核聚变。只有这些可能性。

谢谢你,比尔。

非常感谢。这次聊天很有趣。(财富中文网)

译者:夏林

本文是《财富》杂志气候变化突破方案系列报道的一部分,客座编辑为比尔·盖茨。

动笔十多年后,比尔·盖茨的新书《如何避免气候灾难:我们拥有的解决方案和我们需要的突破》终于面世。“如何避免”那部分做起来并不容易,但盖茨计划的明确性和紧迫性,可能会让数百万读者迅速积极响应起来。

《财富》杂志希望进一步深入挖掘,探索盖茨和其他人提出的挑战。为此,我们邀请这位著名的慈善家担任2月16日当天《财富》杂志的“客座编辑”。

本书出版之前,《财富》杂志主编黎克腾,跟微软联合创始人也是投资人盖茨坐下长谈,讨论如何才能防止气候变化恶化,新能源“奇迹”传递错误信息,以及当前盖茨向哪些领域大举投资。至于讨论中谈到了他对人造肉汉堡(以及其他一些著名投资人的少量“投资目标”)的浓厚兴趣,则是意外收获。

为了简洁及表述清晰,对话经过编辑。

比尔,你刚刚写了避免“气候灾难”的书,然而现在地球上大多数人都在关注另一场灾难——新冠病毒。你担不担心读者可能没准备好同时面对两种威胁?

先说说我为什么要写这本书。2008年,在我离开微软的几年前,在微软工作的一些朋友说:“比尔,你应该关注气候变化问题。”

我读到瓦茨拉夫·斯米尔的书,对钢铁、水泥、电力等物质经济产生了浓厚的兴趣。他让我意识到,人们对轻易获取各种资源感觉理所当然。

比如电力非常可靠又廉价,斯米尔在书中谈到电力普及方面各种令人惊叹的工作。当然,这些工作也是导致温室气体排放和加剧气候变化的因素。所以我开始思考如何改变一切。我在想:“真能实现吗?”

当然,基金会在贫穷国家已经在做各种工作,经济欠发达国家的建筑通常是用废旧金属建造。没有输电线。用水方面,一些地区的屋顶上装有小型水箱,因为当地没有给水系统,即便有也极其不可靠。

后来,朋友介绍我认识了肯·卡尔德拉教授(卡内基科学研究所)和大卫·基思教授(目前在哈佛大学执教)。我们一年开六次会。他们也会介绍其他专家参加,我们选择某个话题,比如储存能量、电动汽车或炼钢,提前阅读大量材料,然后讨论半天。我对相关话题非常感兴趣。

我的理解框架其实不少,2010年我在TED发表了演讲(题目叫“从零开始创新”),一共讲了三场。其中一场关于政府预算问题在哪,我保证总有一天这会被当成预言;2015年的演讲关于疫病,可能是到现在浏览量最高的一场(编者按:该场有先见之明的TED演讲标题是“下一次大爆发?我们还没有准备好。”目前浏览量已经达到3900万次。);关于气候的那场并不长。我想想,大概15分钟?——可以找来看看。

那场演讲的目的是:“困难太大,需要创新——很多创新。”尽管我现在比十年前知道得更多,但那仍然是我的基本认识框架,也是新书的框架。

但就像现在一样,十年前你在TED上发表关于气候变化的演讲时,全世界也被另一场全球危机分散了注意力。

不幸的是,2010年左右那段时间里,也就是金融危机之后,(应对)气候变化的能源消耗大幅下降。然后随着经济开始复苏,兴趣稍微上升。

对我来说,之后一个重大里程碑是2015年巴黎气候谈判之前一年,当时我对大家说:“为什么人们开这些会议,却不讨论研发预算和刺激创新的想法?”

大概结构是:“我们以国家身份来谈谈近期进展。”最近在风能、太阳能发电,以及电动汽车应用方面有些进展。并不是说这些事情很容易,但这都是最容易做到减排的手段。

所以当你说:“五年后或者十年后能够做什么?”人们并不会答:“我正用全新的方式炼铁。”因为各国炼铁方式差别不大。钢铁在全球都是具有竞争力的行业。因此,温室气体排放70%以上的来源从未出现在“让我们讨论下短期减排”的讨论中。奇怪的是,真正难推动的领域几乎没人讨论过,占排放70%的钢铁、水泥或航空就是很好的例子。

但到了2015年,在COP21(跟当年巴黎联合国气候变化大会同时举办的可持续创新论坛)上,这问题被提了出来。

法国组织者想做一些不同的事情,他们希望(印度总理纳伦德拉)莫迪能来。莫迪并不想参会,然后被追问“短期减排多少?”因为印度的电力需求是现在的五倍,才可以让大部分人口维持基本的生活方式。所以他不会出席。

但是,COP21的附带结果也就是所谓的使命创新,不仅关注增加能源研发预算,还要确保有私营部门投资者愿意承担风险,将有希望的创意转化为公司,前提是研发实验室将创意变为现实。

当时,Kleiner Perkins的约翰•多尔或维诺德•科斯拉的风投基金做了大量绿色投资,业绩并不好。Kleiner Perkins赌的是菲斯克(汽车)而不是特斯拉。很多太阳能电池板方面的(投资)并不顺利。所以我承诺筹钱向该领域投资。

后来就成立了突破能源风投基金,隶属于我旗下主要关注气候变化的机构。公司覆盖几个不同的领域,包括专注政策解决方案的部门。不过当前主要是从事风投。

我们筹集了刚好10亿多美元,现在投资了50家公司,进展很顺利。我们也找了其他人投资。

本书出版的时候(2月16日),我们称之为BEV2的风投基金已经融到数十亿美元,将继续投50家公司,其中大部分都会失败。即便是成功也比典型的软件公司更难,因为需要投入大量资金,还需要产业合作关系。所以这是完全不同的投资方式,我的目标是帮助扩大创新规模。

但是,就在你扩大投资规模还召集其他投资者和决策者关注能源领域的激进创新时,赶上了新冠疫情。你似乎把注意力和慈善事业放在寻找新冠治疗方法和疫苗上,去年9月你接受《财富》杂志采访时谈到过。

这应该夸一夸这一代的人们,即便当前身处疫情中,大家也还是真正关心气候危机的。

这次不像金融危机(2007年-2008年)期间,当时人们说,“现在情况很艰难,没有工夫管气候变化。”即便到2010年,如果对公众民意调查,也会发现人们对气候的兴趣已经下降。

而在接下来十年里,关注又逐渐增加,遭遇疫情时我还在想:“会出现什么情况?”实际上,疫情期间人们对气候变化的关注有所上升,这有点奇怪。

看看拜登总统挑选的专家,也是差不多情况,这届政府里,有很多气候问题专家。总统正关注着几个互相叠加的危机,疫情和气候变化重要性相当,这点相当让人赞叹。

而且总统初选和大选期间,候选人遇到的气候问题数量比以往都要多。再看看欧洲的复苏计划,资本投资也极其倾向气候变化领域。超过三分之一的资金都与此有关。

所以我感觉很幸运,在某种程度上年轻人提升了话题的重要性。我年轻的时候都没做到。当时我都没上街游行。

我的观点是,“既然你们如此关心,而且能够理想主义地说:‘让我们尽一切努力在2050年之前实现零排放’——就应该制定相应的计划,根据计划逆推,然后说:‘钢铁、水泥和航空要怎么做?’”

不希望人们想:“哦,我们只想确保多装几个太阳能电池板。”然后10年过去,排放并没有什么变化。

所以除非计划得当,否则最后只会引发很多愤世嫉俗和失望。

所以你决定把计划写成书。

是的,新书主要说的是计划。书中没具体解释为什么气候变化有害,但还是用一章的篇幅大概讲了讲,还有一章关于适应的。但书中大部分内容主要还是类似于:“温室气体排放达510亿吨,以下列举出排放的领域。”看看各领域的情况,然后说:“如果想实现零排放,达到同样产量成本的情况下,要贵多少?”

这就是我说的绿色溢价指标。我们能够讨论的是:“当今水泥的绿色溢价是多少?哪家公司的技术能够实现减半?有没有可能降到零?”

将绿色溢价降到零是很神奇的,未来十年电动汽车将能实现这个目标。也就是说,不需要政府资助创新,也不需要个人资助。只要量达到一定程度,产品变得便宜,充电站也变得普及,政客就可以参与。

到时政客就能够说,2035年、2040年之前禁止燃油车,公众不会震惊地问:“什么?!”

如果绿色溢价降到接近零,相关政策的实行就成为可能,不过在大量碳排放的地区也要采取同样措施。有些领域,比如钢铁或水泥生产实施起来都很困难。不管怎样,这都是最基本的。

我非常喜欢这本书的一点是,读者可以体验学习气候科学的过程。举例来说,你对汽油比苏打水便宜感到惊奇,或者解释为什么某些气体吸收或反射太阳辐射取决于原子组成时,感觉好像你正在高兴地跟读者分享发现。在写书的过程中,你有没有意识到要分享个人发现之旅?

对我来说,所有东西都很有趣。

当你在其他某些地方读到相关内容时,对内容的解释经常并不清晰,比方说,你会读到文章说:“减排力度相当于10000户或40000辆汽车。”

你得想:“我得费劲理解数字,总数是多少,然后算这些数字占多少?”

我想把数字简化,如果有人谈到10000户或40000辆汽车碳减排时,我就能够回答这个问题:“占总碳排放量的百分比是多少?”

大多数人读到相关文章时会说:“这些都只是胡言乱语。”当一开始努力理解时,能量单位都非常大,容易让人感觉混乱。对我来说,能够利用某些熟悉的事物去理解比较有吸引力。

必须承认,这本书非常感谢肯·卡尔德拉和大卫·基思,他们向我传授了很多知识,还介绍了很多人。

还有像(微软前首席技术官)内森·米尔沃德和(多产发明家)洛厄尔·伍德等人,每当我对物理或化学方面有疑惑时,就给他们写邮件。当然还有瓦茨拉夫·斯米尔,他写了很多书,对诸如1800年工业经济的概况和之后的重大突破的着迷,为我提供了灵感。

我很喜欢研究这些。其实很简单。跟大多数领域一样,就这么几个概念,但必须真正了解它们。

比如能量速率、能源数量,以及储存时间。

对能源来说,这些相当于“能不能想用的时候就用?”斯米尔做了直观展示,“一座城市耗能量多少,或者一个家庭耗能量多少?”这样脑中就能理解各种数字和常识。

为了理解,我带儿子去煤矿工厂,还去了水泥厂和造纸厂实地参观。因为我们只懂软件,在化学实验方面实在不擅长。

以前我想的是:“只算化学方程式就好,别用试管实际操作。我可能造成爆炸。”

成长过程中,我从没有造过小火车或飞机之类的物品。所以我一直觉得:“上帝,实体的东西才是真的。”

我是说,得有人真去建造机器和工厂。

不管怎样,学习很有趣。如果告诉别人我花了多少时间或者读了多少书,就得小心点,因为听起来像是吹牛什么的。但我最大的优点就是喜欢当学生。

我很喜欢的说法是,只要了解得足够多,实际上什么事情都很简单。我有足够的信心,还有很聪明的朋友,他们会帮我达到目标,我可以说:“我要学习,最终达到一切都能够解释通的程度。”

在书中的某些部分,你似乎在凝视未来。去年秋天我读到第一版书稿中,你提到“美国退出2015年巴黎协议”,还说“之后美国总统拜登会将其逆转”。你早在美国总统大选前就能够预测到,真令人惊讶。

书中的大部分内容实际上是在10个月前就完成了的。我当时考虑了很久,要不要出版。

刚开始问题是,如果特朗普连任,显然会影响美国按照书中呼吁行事的能力。这本书主要关于创新,美国控制着当今世界50%以上的创新能力,创新会发生在大学里、国家实验室里,还有风险投资当中。如果不让美国推动创新,那么全世界创新都会停滞。因为在美国,创新不仅仅为了本国公民,也为了其他人。

如果我们可以廉价制造清洁(无碳)水泥,30年后当发展中国家为人民建造住房时也会选择清洁水泥。

所以当我写作时,最后几章变得非常复杂,我不得不琢磨措辞,“如果民主党候选人当选……”等等。

还有疫情来袭,我想,“哦,人们注意力可能有点分散。”

所以在大选后,我决定对书做点修订,也许增加一些技术进展。大选后我对书完整检查了一遍,又加了些内容。

从第一章到第九章,几乎没有重大修订。但到了第10章至第12章,谈及政府政策等相关问题时,我做了相当多修改。即使民主党控制了白宫和国会、参议院几乎平分秋色,而且美国已经陷入赤字,我们也必须拿出不需要大量资源的计划。

这是可行的,我相当乐观。

其中涉及的政治太复杂。在第11章路线图中,你提出了激励和抑制或惩罚政策措施,也就是胡萝卜和大棒。但过去我们看到,棍子更难到位。

以《平价医疗法案》为例,行政部门和国会两院中民主党占多数,仅仅是个人授权和相关处罚的概念就已经导致立法内战,而且到如今仍在持续。

我读到书中关于碳价格设定部分,实际上是“碳税”,税率高到能够抵消绿色溢价,我想知道你对近期实现的把握有多大?正如你写到:“为碳排放定价,是消除绿色溢价能做的关键事项之一。”

如果没有创新,即便碳捕获可以降到比方每吨100美元,仍然要面临巨大挑战,因为每年碳排放量有510亿吨。在世界上某个地方必须找到每年5万亿美元的支出,占世界经济5%以上。这是不可能的,没机会。

当然,从政治上征收任何形式的碳税都非常困难。法国试图提高柴油价格时,人们大喊:“嘿,不能这么做!”类似努力不可避免地被减弱,因为实施起来的收获与人们的感受并不成比例。

可以尝试进行弥补,但在法国的例子中,住在城市之外不得不开车赶路的人,觉得住在城市的精英忽视了自己,这也是各个富裕国家普遍存在的政治现象。最终法国还是废除了柴油税。

现在公众不太愿意掏钱避免负面影响,毕竟这些负面影响大多在遥远的未来。我是说,确实有一些有关天气的负面现象已经显露,比如森林火灾,还有非常炎热的日子。

很高兴人们已经注意到,如果目前不采取行动,如今的负面影响将无法与2080年和2100年的境遇相比,对生活在赤道附近的人来说更是如此。到2100年,夏天在印度户外活动将难以忍受。户外工作根本不可能,毕竟身体的排汗量是有限的。

书中接近结尾的地方,你总结实现零排放的计划时谈到“加速创新需求”。这一概念似乎对成功非常关键,而且似乎跟你在慈善事业中做的很多工作也有所不同。你跟梅琳达创立的基金会经常资助创新投资的公司。但在一些根本不存在市场的地方开创建立需求侧,是另一种挑战。

例如在制药行业,制药巨头通过大量生物技术初创公司为创新提供市场,跟有希望治疗某种适应症的实验候选药物竞争。气候方面是否也有类似模式,即能源巨头为能源初创企业在零排放方面的进展提供现成市场?还是像国防工业创新一样,“市场”必须由政府提供?

能源方面难得多。相比之下,软件反而最简单。医学的难度介于中间。与气候有关的事情最困难。

软件方面,总有一些客户不喜欢现有的软件,认为应该更简单、更便宜,或者在某些方面功能更多。只要能从垄断巨头那里抢来一小块市场,就可以服务某些客户,因为你能够更好地满足需求。软件创新者面前有现成的市场。

医药也一样。看看各种各样的疾病,也许新产品是口服而不是注射,或者能够减少一些副作用。或者,希望每隔一段时间找到全新的方法治疗不治之症。但这一行业同时也要面临各种监管、检查和副作用等问题。

气候变化方面最困难的是,制造清洁钢铁除了能够保护地球之外,并没有额外益处。如果仅仅是跟传统上公认的工艺略有不同,买家很可能发出疑问:“耐用吗,会变脆吗,会生锈吗?”

人们对任何变化都抱着怀疑态度。因为钢铁非常可靠,水泥也一样。有个公式可以精确计算强度,测试本身不是为了测试特性,只是测试是否遵循了公式。因此,市场中并没有专门一块愿意为清洁钢铁或水泥支付更高价格的。

现在太阳能电池板的情况是,卫星需要能源,太阳能电池板是唯一的方法。哪怕不经济,德国和日本也买了。量不大,但足够启动学习曲线。然后包括美国在内其他国家实施税收抵免,学习曲线逐渐扩大。

我们已经看到学习曲线模式在风能和锂离子电池上的应用,这是算是奇迹。

可悲的是,大多数人认为,“电池做得够汽车用,就可以做得能够让整个电网都用,我们要在电网创造另一个奇迹。”但他们没有意识到,很多希望创造奇迹的尝试,比如燃料电池或氢动力汽车都还没有成功。

举个例子,在裂变动力核反应堆方面,创新还有其他难点。成本和安全问题引发的担忧非常大,除非用全新设计重建反应堆,在经济性和安全性上彻底革新,否则前路只会是死胡同。这就是我在(核能公司)TerraPower(盖茨担任董事会主席)努力做的事情。

如果把过往的成功投射到这些领域,最后可能认为事情比实际情况简单得多。你提的问题非常好,因为书中描述整体战略的一部分,就是为清洁钢材找买家。

假设现在绿色溢价是每吨100美元。有人创办一家每吨溢价仅50美元的清洁钢铁公司,你会对那个人说:“干得好!”但事实上市场规模为零,因为每吨多出50美元,只意味着成本更高。

现在我们要做的是努力让资金更充裕的公司,比如科技巨头同意每当建造新大楼,就要使用20%的清洁钢材。回报是可以对外宣称:“大楼用了20%的清洁钢材。”

所以我们得创造需求侧。我热爱创新的供给端,要去找教授,找有疯狂创意的人。所以突破能源投资公司有很多类似的项目。

基金投的50家公司中,有一家发现向地下注水并在地下岩层之间储存可长期储存能量。要注水就需要能源,如果电力充足就能够做到。然后如果想使用能量就打开井,放出高压水为涡轮机提供动力。

但估计该创意无法实现。公司叫Quidnet,估计名字是为了致敬哈利·波特之类的。不管怎样,资助此人就代表了我们的倾向。这就是供给侧创新。

需求方同样必要,可以用人造肉公司为例。令人惊讶的是,人造肉市场由消费者的选择驱动。当汉堡王开始提供人造肉汉堡时,需求量非常高,这是好事。

然而在钢铁和水泥行业,清洁技术实在晦涩难懂,要创造需求就困难得多。航空燃料方面,清洁燃料的额外成本,意味着机票要高出25%。鸡尾酒会上人们可能会说,愿意多付25%。但我怀疑如果真到了紧要关头,支付绿色溢价的消费者能否负担总体成本。

因此,为钢铁水泥产业打造创新市场,比为软件和医疗行业都困难得多。这可能是突破能源投资设定了20年有效期和不同的激励机制的原因。投资者都知道,大多数公司的成功几率很小。

你有没有想过向公众投资者开放基金或类似基金,还有让人们购买份额以协助开创需求?

我们还没有想到这一步,但我认为如果企业能够按照每吨价格估算清楚碳排放量以及成本,就可以劝说企业写支票解决问题。

原则上来说,这些支票能够资助基金竞拍,可以这么说:“谁能以最低价格提供清洁钢铁?谁能供应清洁水泥?”

所以我比较认同,不管是对自己的碳足迹感到内疚的个人还是企业,尤其是利润丰厚的企业,都可以认购基金,就像航天工业支持太阳能电池板一样。换句话说就是创造需求。

这是我想组织的事。某种程度上人们会说,“我也为突破能源采购做出了贡献”,并为此自豪。

你可以像沃伦•巴菲特在伯克希尔•哈撒韦那样,为富裕企业创建A股,为其他人创建B股。

是的,区分白金和黄金。

如果说,能从观察你长期得慈善事业中领悟到什么,应该就是你似乎一直是围绕着人们所说的先行者做事。如果你可以改造X,就能够减少X带来的不良后果。

因此,当你和梅琳达创立比尔及梅琳达盖茨基金会时,合乎逻辑的第一步是投资全球卫生,努力消除疟疾、腹泻病、不受重视的热带疾病、小儿麻痹症等。当然,减少每年生病和死亡的儿童人数本身不仅是好事,理论上也会带来一系列好效果。首先,确保更多健康又有生产力的公民振兴发展中国家的经济,就可以减少地方性贫困。

所以如果你能够解决某件事,就能对下游一些事产生积极影响。基金会在教育方面的投资也有类似的乘数效应,尤其是年轻女性和女孩的教育方面。正如梅琳达所说,5岁以下儿童死亡率的首要指标是母亲的教育状况。如果能解决这个问题,就可以帮助一代又一代人脱贫。

其他主要投资上也遵循同样思路:例如改善卫生条件可以减少霍乱、伤寒、腹泻病、痢疾等等。

现在你大力转向气候变化领域,可以说这可能是一系列问题中的终极“先行者”,如果不加以阻止更是如此:要么解决气候变化问题,要么迎接世界末日。

如果推理没问题,多年来你和梅琳达关注的各种事务中,气候变化的地位是不是越来越重要?在各种迫切需求上,你怎么分配时间、注意力和资金?

在基础领域,也就是全球健康问题上,每一美元的影响都是巨大的。我们拯救每条生命的代价不到1000美元。之后可能会出现市场失灵,因为发达国家并不存在疟疾,所以并没有指导创新者开发疟疾药物和疫苗的市场信号,也没有消除疟疾的总体战略。疟疾流行的贫穷国家却没有消除疟疾的资源。

我投出第一笔3000万美元抗击疟疾时,成了疟疾领域最大的资助者。这可以说是一种悲哀,这也许是显著推动变革的机会。

从事气候变化的人们都谈论碳捕获。我是各家公司最大的出资人,大概投了数千万美元,其中包括Climeworks、Carbon Engineering和Global Thermostat等。碳捕获领域有四五家公司。幸运的是,还会有更多,因为它们有不同的方式。

每当我发现某些投资,如果成功的话,每一美元的社会影响大概能有千倍回报,我感觉就像风险资本家投了早期谷歌或类似公司一样。这很吸引我。

随着时间推移,看到潜在的创新获得成功,我很开心。我喜欢和可以同样看得远并愿意保持耐心的人们一起工作。甚至某些情况下,我们还押注多种途径,虽然明知其中一些会失败,例如预防或治疗艾滋病。花很多钱投入到不同方法中,即使最后只有一种方法奏效,那也是一种奇迹。

关键是创新思维。有些事,比如改善美国的教育,如果采取宽泛的指标,如“美国学生在数学、阅读和写作表现如何?”或者“有多少孩子从大学辍学?”我们对全球卫生工作的影响还没有这么大。

我们仍然相信我们可以产生影响,也在加倍努力。在疫情期间,更多孩子真正拥有笔记本电脑并连接互联网的想法得到了极大的推动,真正建立了非常不同的新一代课程。

即使目前影响几乎很难察觉的领域,也还是存在希望。事先不会知道能发挥什么作用。解决问题的大多数努力都比想象中困难。

有些事,比如我投钱给Beyond Meat和Impossible Foods时,从一开始我就说:“改造肉”就像制造零碳钢和水泥一样困难。现在虽然还没有解决,但已经有了出路。情况跟电动汽车差不多,就是成本降低和质量提高,合成人造肉方面的具体表现是,出现各种生产方式,绿色溢价将为零。生产速度真的快到让我很吃惊。

书中让我吃惊是你对能量储存自然极限的信念。有些人仍然把希望放在近乎无限大的蓄电池上,或者至少是容量超大的蓄电池,如此一来可以让太阳能、风能等途径获取的电力更容易储存。

在我看来,这也是书中让人难过的一块。储存能量方面不能应用摩尔定律的观点让人很难接受。

是啊,摩尔定律能够持续这么久已经很令人兴奋。软件和数字技术让人们认为总是有可能出现奇迹,然而实际上进步更像百年来汽油里程的变化。如果爱迪生复生看到我们的电池,他会说:“哇,这些电池比我发明的铅酸电池好四倍。干得好。”电池百年创新不过如此。

人们混淆了电动汽车电池和行驶里程的区别,里程再扩大两倍就非常理想,而电网储存的电池目的是夏天收集太阳能,然后冬天使用。这个例子中,一整套电池整体只能够发挥一次作用,即每年可以使用一次电力。

成本和规模化非常困难,我们还有20倍的差距。我在电池公司亏损的钱比其他企业都多。现在我在五家电池公司工作,有几家直接参与,也有几家是通过BEV(突破能源投资公司)。

解决电网问题只有三种方法:一是储存方面出现奇迹,二是核裂变,三是核聚变。只有这些可能性。

谢谢你,比尔。

非常感谢。这次聊天很有趣。(财富中文网)

译者:夏林

This article is part of Fortune’s Blueprint for a climate breakthrough package, guest edited by Bill Gates.

More than a decade in the works, Bill Gates’ new book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, hits shelves today. The “how to” part is anything but easy. But the clarity of Gates’s plan—and the reason for absolute urgency—may well turn millions of readers into overnight activists. (It should.) At Fortune, we wanted to dig deeper, exploring the challenges that Gates raises and a bunch of others as well. To that end, we’ve asked the famous philanthropist to serve as “guest editor” of Fortune for the day.

In advance of the book’s publication, Fortune editor-in-chief Clifton Leaf also sat down with the Microsoft cofounder and high-stakes venture investor for a sprawling conversation about what needs to be done now to stop climate change in its tracks, the energy “miracles” that are sending the wrong message, and where he’s placing his multimillion-dollar bets right now. That our discussion took us to his fascination with the Impossible Burger (and a smattering of “dish” on some other famous investors) is just gravy.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Bill, you’ve just written a playbook for avoiding a “climate disaster” when much of the planet is still focused on another disaster—the coronavirus. Did you have any concern that readers might not be ready to engage with two existential threats at the same time?

So just a little bit, first, about why I wrote the book. It was a few years before I left Microsoft in 2008 that some friends who worked there said, “You know, Bill, you should get involved in the issue of climate change.”

I had already developed a fascination about the physical economy—things like steel, cement, electricity—by reading Vaclav Smil. He got me thinking about the fact that we take the ease of these things for granted. Electricity, for example, is so reliable and so cheap, and Smil talks about all the amazing work that went into that. But these are things that contribute to greenhouse gases and driving climate change, of course. So I began thinking about the idea that this was all going to have to change. And I thought, “Is that really gonna happen?”

Of course, the foundation was doing all this work in poor countries, where buildings are often built out of scrap metal. There are no transmission wires. For water, in some places, they have little tanks up on their roofs because the distribution system doesn’t exist or if it does, it’s super unreliable.

So anyway, my friends introduced me to a couple professors—Ken Caldeira [at the Carnegie Institution for Science] and David Keith [who’s now at Harvard]. And I think we started meeting six times a year. They would bring other experts in, and we would take a topic like storing energy or electric cars or making steel, and we’d have a half-day discussion with a lot of reading in advance. I was fascinated with the topic.

And I had enough of a framework that I gave a TED Talk in 2010 [called “Innovating to Zero”]; I have three given three of those talks. I have one about how government budgets are a problem—and I promise you, someday that will be viewed as an advanced warning. I have the 2015 one on the pandemic, which is now probably the most viewed thing I’ve ever done. [Editor’s note: That prescient TED talk, “The next outbreak? We’re not ready,” has now been viewed 39 million times.] But the one on climate—it’s not very long. I think, what is it, 15 minutes?—you might look at that.

The point of that talk was to say, “Look, this is superhard and requires innovation—a lot of innovation.” And even though I know a lot more today than I did a decade ago, that’s still my basic framework. I have to admit, that’s my basic framework for anything. That’s the framework for the book.

But just as it is now, the world was also a little distracted by another global crisis a decade ago when you gave your TED Talk on climate change.

Unfortunately, in that time period—circa 2010, after the financial crisis—the energy [for addressing] climate change goes way down. And then, as the economy starts to recover, interest goes up a little bit. So the next big milestone for me was the year in advance of the Paris climate talks in 2015 when I was saying to everybody, “Hey, how come they have these meetings and the idea of an R&D budget and spurring innovation is not in the meeting?”

The framework is just, “Hey, let’s come in as countries and talk about our near-term progress.” And there has been near-term progress using wind and solar for electricity generation and using battery electric-powered cars. And I’m not saying those things are easy, but those are the easiest sources of emissions to lower. And so whenever you’re just saying, “Okay, what can you do five years from now, or 10 years from now?” nobody comes to the meeting and says, “Okay, I’m making my steel a whole new way.” Because making steel is not something one country does differently than other countries. Steel is a globally competitive industry. And so the various sources that cause over 70% of our greenhouse-gas emissions never come up in those, “Hey, let’s reduce short-term emissions” discussions. Weirdly, the hard stuff—the 70% that steel and cement or aviation are great examples of—almost doesn’t come up at all.

But then, in 2015, at the COP21 [Sustainable Innovation Forum—held alongside the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris that year], it does come up. The French organizers wanted to do something a little different—and they wanted [Indian Prime Minister Narendra] Modi to come. And Modi didn’t want to come for the, “Hey, what’s your short-term reduction?” game—because India still needs five times as much electricity as they have today in order for much of the population to live even a basic lifestyle. And so he wasn’t going to come to that. But this side thing at COP21, which was called Mission Innovation, was not only focused on upping energy R&D budgets, but also on making sure there were private sector investors who are willing to take the risk—to turn these promising ideas into companies—if R&D labs turn the ideas out.

At that time, the bulk of the green investing was being done by people like John Doerr at Kleiner Perkins, or by Vinod Khosla’s venture funds—and, you know, they hadn’t had a very good track record. Kleiner Perkins had bet on Fisker [Automotive] instead of Tesla. There were a lot of solar panel [bets] that didn’t go well.

So I made a commitment to raise money to invest in the space.

And that became Breakthrough Energy Ventures—which is part of Breakthrough Energy, the umbrella for everything I do on climate. Breakthrough Energy has a few different areas to it, including an arm that focuses on policy solutions. But the venture investments are the biggest aspect at this time. (You can read our inside look at Breakthrough Energy here.)

So we raised that fund—with just over a billion dollars. And actually now, we’ve invested in 50 companies. That’s gone super well. We’ve gotten other people to invest. And by the time this book comes out [today, Feb. 16], we’ll have the billion dollars for what we’re calling BEV2, which will be the next 50 companies—you know, most of which will fail. And even the ones that succeed will be harder to get there than your typical software company due to the amount of capital involved and the kind of industrial partnerships you need to make them work. So it is quite a different kind of investing. My aim is to help scale that innovation.

But as you’re scaling up these investments and rallying other investors and policymakers to focus on these radical energy-related innovations, the pandemic hits. You yourself seemed to concentrate your attention—and your philanthropy—on finding therapies and vaccines for the coronavirus, which you spoke to Fortune about in September.

So the current generation, you gotta give ’em credit: Even through we’re in the midst of a pandemic, people truly care about the climate crisis, too. It’s not like it was during the financial crisis [of 2007–08] when people were like, “Hey, things are tough now, and that climate stuff, that’s way out there.” Even by 2010, if you polled the public, you’d find that interest in the climate had gone way down. It began to build up gradually over the next decade, but as we hit the pandemic, I thought, “Okay, what’s gonna happen?” But it’s actually gone up somewhat during the pandemic, which is kind of weird.

Likewise, look at the experts President Biden is picking—he’s putting climate people throughout the administration. And he says he’s focusing on several overlapping crises—you know, the pandemic and climate change are there at the same level, which is pretty impressive. And, of course, during both the presidential primaries and the election, the number of climate questions asked to the candidates was greater than we’ve ever seen. Or look at the European recovery plan, its capital investment is very climate-oriented too. Over a third of those dollars are connected to that.

So I feel lucky, in a way, that young people are making this topic important. And I didn’t do that when I was that age. You know, I wasn’t blocking traffic.

But my view is, “Hey, since you guys care about this so deeply—and you have the idealism to say, ‘Let’s do what it takes to get to zero by 2050’—you really deserve to have a plan where you work backwards and say, ‘Okay, what has to happen to steel and cement and aviation?’” The last thing you’d want is to have people think, “Oh, we’ll just make sure there’s a few more solar panels.” And then, 10 years later, emissions haven’t changed. And so unless there’s a plan, you’ll just end up generating a lot of cynicism and disappointment.

And so you decide to lay out that plan in a book.

Yeah, so my book is about the plan. It doesn’t explain why climate change is bad. Okay, I have one chapter on that. And I have a chapter on adaptation. But most of the book is this: “Hey, there are 51 billion tons of greenhouse-gas emissions. Here are the sectors that are responsible for those emissions.” And then we can look at each sector and say, “Okay, how much more expensive will it be to produce the same results with zero emissions?”

And that amount is the metric I called the Green Premium. So you can ask: “Okay, what’s the Green Premium today for cement? Is there a company out there whose technology can cut that in half? Is there any chance it can get to zero?”

Getting the Green Premium to zero is magic, which will happen for electric cars over the next decade. That is, you won’t have to government-subsidize the innovation or subsidize it from your individual budget. Once you’ve gotten that volume, and things have gotten cheaper, and you have the charging stations, etc., then the politicians can have some involvement. They can then say they’re going to ban gasoline cars by, you know, 2035, 2040, and the public doesn’t go, “What?!?”

If that Green Premium gets down close to zero, such a policy becomes possible. But we need to do the same across all the areas where we have lots of carbon emissions. And some of the areas, like in steel production or in making cement, are just superhard. So, anyway, that’s the basic thing.

One of the things I really like about the book is that the reader gets to experience your own learner’s journey into climate science. Every time you marvel about a fact—like that gasoline is cheaper than soda, for example—or explain why certain gases either absorb or reflect the sun’s radiation depending on their atomic makeup, it feels as though you are, somewhat joyfully, sharing that discovery with us. How conscious were you about sharing that personal journey of discovery in writing the book?

For me, all this stuff is so interesting. But when you read about it somewhere, it can often seem really opaque—like you’ll read an article that’ll say, “Oh, this reduction is equivalent to 10,000 houses or 40,000 cars.” There comes a point where you’ve really got to decide, “Am I going to take the effort to understand, numerically, what the total is or not—and then understand what these pieces of the total are?” I wanted to do the fairly simple math, so that when someone talked about the carbon reductions from those 10,000 houses or 40,000 cars, I could answer the question, “Okay, what percentage of the total carbon burden is that?”

When most people read those articles, they’re like, “It’s just gibberish.” And at first, when you try and get it, the number of energy measures are so large that, you know, it’s very confusing. For me, it was appealing to just map it to one thing.

I have to admit, my book owes a lot to Ken Caldeira and David Keith, who educated me and brought all those people in. And then there’s people like [former Microsoft CTO] Nathan Myhrvold and [prolific inventor] Lowell Wood, who, whenever I get confused about physics or chemistry, I just send them an email. And, of course, this guy Vaclav Smil, who’s written so many books—his fascination with what the industrial economy was like in 1800 and the great breakthroughs that followed has been an inspiration. I love this stuff. And it is actually simple. As with most areas of domain, there are only a few concepts, but you really have to get those concepts.

There’s the rate of energy, the amount of energy, and how long you can store it. For power, these all add up to “Can you use it when you want to use it?” And so Smil does these things where he shows, “Okay, how much does a city use, or how much does an individual household use?” And so you can get those numbers and that kind of common sense in your head.

As part of this, I actually took my son to a coal plant. And then to a cement plant and a paper mill just to see these things. Because we software guys are—I mean, I was terrible in the chemistry lab. So I was like, “Let’s just do the equations of chemistry, not, you know, do the stuff in those test tubes. I might blow something up.”

Growing up, I didn’t build little trains or planes or anything like that. So I’ve always felt, “God, that physical stuff, that’s the real thing.” I mean, somebody built those machines and those factories.

Anyway, yes, it’s been fun learning all this stuff. If I say to people how many hours I spent with those guys or how many books I had to read, I have to be careful because that sounds like bragging or something. But my greatest benefit is that I love being a student. And I love the idea that if I learn enough, it’ll actually be simple. I have enough confidence in that—and in smart friends who will help me get there—that, yes, I can say, “Okay, I’m going to learn about these things and eventually get to the point where it all fits together.”

At one point in the book, you seem to have gazed into the future. In the first galley that I read way back in the fall you mention “the U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 Paris Agreement” and say that it’s “a step that U.S. President Joe Biden later reversed.” It’s amazing that you knew that had happened long before the election.

Most of the work on this book was actually done about 10 months ago. I thought a lot about whether I should put the book out then. At first, the question was, if Trump gets reelected, then the U.S. won’t lead—and that would obviously affect our ability to do the things I call for in the book. You know, this book is about innovation, and the U.S. controls maybe greater than 50% of the innovation capacity in the world today—it’s in our universities, national labs, venture capital. And so if you don’t have the U.S. pushing its innovators, then that’s felt all around the world. Because in the U.S., we’re not just innovating for our own citizens, we’re also innovating on behalf of everyone else. If we learn to make clean [carbon-free] cement cheaply, then 30 years from now, when developing nations are housing their people, they’ll choose the clean cement.

And so, as I was writing, the last few chapters got really convoluted, having to couch things in, “Okay, if a Democrat gets elected…” and so forth. And then the pandemic hit, and I thought, “Oh, people might be a little distracted.”

So I just decided to do a postelection revision of the book and maybe add some technical advances. And so I did a whole run-through of the book after the election—and I was able to put a number of things in. On chapters one through nine, there were very few edits of any significance. On chapters 10 through 12, where I talk about government policy and the like, I actually did make a fair number of changes. Even with Democrats controlling the White House and Congress, with the Senate nearly evenly split—and with the kind of deficit we’ve gotten into—we’re going to have to come up with a plan that doesn’t require a huge level of resources. But that’s very doable. I’m actually quite optimistic about that.

The politics of this are so complex. In your road map in Chapter 11, you suggest both incentives and disincentives or penalties, in terms of policy initiatives—both carrots and sticks. But in the past, we’ve seen that the sticks are much harder to put in place. In the case of the Affordable Care Act, for example, where there was a Democratic majority in the executive branch and in both houses of Congress, the mere concept of an individual mandate and an associated penalty ended up causing a legislative civil war—one that’s still going on to this day. So when I came to the part in your book about setting a price on carbon, effectively, a “carbon tax,” big enough to offset the Green Premium, I wondered how confident you were that something like that could actually happen in any near-term timeline? As you write: “Putting a price on emissions is one of the most important things we can do to eliminate Green Premiums.”

Well, without innovation, even if carbon capture can come down to, say, $100 a ton, we’d still have an enormous challenge because we’re emitting 51 billion tons of carbon a year. And so somewhere in the world you’d have to find $5 trillion that you would spend per year. That’s over 5% of the world economy. And there’s just no way, not a chance, that that happens.

Of course, any kind of carbon tax is politically very difficult. When France tried to raise their price for diesel, people shouted, “Hey, you can’t do that!” And inevitably such things are always cut because they fall disproportionately on people. You can try and offset that. But in that French case, the people who lived outside the cities and had to drive longer distances felt the elites in the cities were ignoring them—which is, you know, the general political phenomenon in all rich countries now. In the end, they got that diesel tax repealed.

So there’s not much willingness of the public to pay now to avoid these negatives—most of which are far out in the future. I mean, yes, there are some weather things—forest fires, very hot days—that are happening now. And I’m glad people are paying attention to those. But if we don’t act now, these will be nothing compared to what we’ll get in 2080 and 2100, and that will be even more so for anyone living near the equator. So going outdoors in India in 2100 during their summer months is gonna be unbearable. Outdoor work will be impossible. The body can only sweat so much.

Near the end of your book, as you’re summarizing your plan for getting to zero emissions, you talk about “accelerating the demand for innovation.” That notion is really critical, it seems, to success—and it also seems different from much of what you’ve done in your philanthropic work. In the foundation you run with Melinda, you have often funded the supply of innovation—investing in lots of these startups. But creating markets in some places where they don’t exist—building the demand side—is a different sort of challenge.

In the drug industry, for instance, Big Pharma companies provide a market for innovation through legions of biotech startups, competing to in-license experimental drug candidates that might be promising in one indication or another. Is there a similar model on the climate front, with big energy companies providing a ready market for zero-carbon discoveries from energy startups? Or as with defense industry innovation, will the “market” have to be provided by governments?

You know, energy’s a lot harder. Software, by comparison, is the easiest in this regard. Medicine is kind of in the middle. And these climate-related things are the hardest. In software, there’s always some customer who doesn’t like the current software—and who thinks that yours is either simpler, cheaper, or has more functionality in some area. So you carve off that piece from whoever’s dominant, and you can go after a certain set of customers because you’ve matched up to their needs better. That provides a ready market for software innovators.

Likewise for medicine. You look at the various diseases, and maybe you make something that’s oral instead of injected or that reduces some side effect. Or hopefully, every once in a while, you find a completely novel way to attack a disease that there is no medicine for. There you also have all the regulatory issues and inspection issues and side effects, etc.

With climate, the thing that’s so difficult is that when you make steel—clean steel, there is no added use or benefit beyond what it does for the planet. The mere fact that you’ve made it slightly differently than the historically accepted process is likely to provoke questions among buyers: “Does it last, does it get brittle, does it rust?” People will look askance at any change. That’s because steel is so reliable. Just as cement is. They have a formula for exactly what goes into it. They don’t test its characteristics; they just test that you followed the formula. And so there’s no niche in the marketplace that inherently wants to pay more for clean steel or clean cement.

Now, what happened with solar panels was that there were satellites where you needed a source of energy, and the solar panels were the only way to do it. And you got Germany and Japan to buy them even when it was non-economic. Not a huge volume—but enough volume that you started this learning curve. And then other countries, including the U.S., put their tax credits in, and you got to expand this learning curve. And we’ve seen the learning-curve pattern play out with wind and lithium-ion batteries. Those are three miracles that have happened.

Now, sadly, most people think, “Okay, just because you make batteries good enough for cars, we can make them good enough for the entire electrical grid—and we’ll have another miracle there.” Well, they don’t realize that many attempts at miracles like, for instance, fuel cells, or hydrogen-powered cars, have yet to pan out.

There are other complications with innovating, for example, in the case of fission-powered nuclear reactors. Here, the cost and the fear of safety issues are such that, unless we rebuild the reactor with a whole new design that’s utterly different in terms of economics and safety, that will be a dead end. And so that’s what I’m trying to do with [nuclear energy company] TerraPower [where Gates serves as chairman of the board].

And so if you project the successes we’ve had onto all these areas, you can end up thinking this thing is far easier than it is. And your question’s a super good one because that’s one piece in the overall strategy described in the book, having a buyer for that clean steel.

To that end, say the Green Premium is $100 a ton today. If someone were to come along and start a clean-steel company that has a mere $50-per-ton premium, you’d go to that person and say, “Hey, hallelujah, good job, buddy!” But in fact, that’s a zero-sized market, because $50 more per ton just means it costs more money.

Now, what we’re going do is to try and get richer companies, including the big tech companies, to agree that whenever they build a new building, they’re going to use 20% clean steel. And their reward is they get to say, “Hey, we used 20% clean steel.”

So we have to create the demand side. Your question is a super good one. I, of course, love the supply side of innovation. You know, to go find the professor, go find the guy with the crazy idea. And so Breakthrough Energy Ventures has lots of those. Among the 50 companies in the fund is one where a guy has figured out how to store energy long-term by pumping water into the ground and storing it between underground layers of rock. It takes energy to pump it down, but that can be done when electricity is abundant. Then, when he wants energy back, he opens the well and the pressurized water rushes out, powering a turbine.

And that shouldn’t work. The company’s called Quidnet. I think there’s some reference to Harry Potter, or something. I don’t know why. I should know that. But anyway, funding that guy is an example of what we like to do. That’s the supply side of innovation.

But you need the demand side, too. Take these artificial meat companies. Well, amazingly, their market is driven by consumer choice. When Burger King began offering the Impossible Whopper, the demand was super high, which is good.

But in steel and cement, because the green-tech is so obscure, it’s much harder to create that demand. In the case of aviation fuel, the extra cost of a clean fuel is going to mean your plane ticket is, like, 25% higher. You know, people might say at a cocktail party that they’re glad to pay that 25%. But actually, I doubt that when push comes to shove, that such an effort can be funded by consumers paying the full cost of that Green Premium.

So it is much harder than creating a marketplace for innovation in the software or even medical industries. And that’s probably why Breakthrough Energy Ventures has a 20-year life span and a different set of incentives. It has investors who know that most of the companies in there are likely not to succeed.

Have you have ever thought of opening up the fund, or one like it, to public investors and letting people buy shares in order to help create that demand?

Yeah. We haven’t yet formulated this, but I do think being able to say to companies—as they figure out what their carbon emissions are and the cost of that, estimated at some price per ton—that they should be willing to write a check out to mitigate that. And those checks, in principle, could finance a fund that does an auction to say, “Okay, who can give us green steel at the lowest price? Who can give us green cement?”

And so I like that idea of getting, both individuals who feel guilty about their carbon footprint, and companies—particularly quite profitable ones—who could underwrite a buying fund that does what the space industry did for solar panels: that is, create the demand side. That is something I want to organize. And, you know, people will say, “Okay, I’m a member of this Breakthrough Energy buying effort” at some level and be proud of it.

You could do as Warren Buffett does at Berkshire Hathaway and create “A” shares for rich companies and “B” shares for the rest of us.

Yeah, platinum and gold.

If I might draw a strategy from watching your long philanthropic career it is that you seem to have structured your efforts around what one might call first movers. If you can fix X, then you can reduce all the bad outcomes that cascade from X.

So when you and Melinda began the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a logical first step was to invest in global health, working on ending scourges like malaria, diarrheal disease, neglected tropical diseases, polio, and others. Reducing the number of children who get sick and die each year was not only a good thing in itself, of course, but it would also in theory cause a cascade of good effects: reducing endemic poverty, for one thing, by helping to ensure that there were more healthy, productive citizens to strengthen a developing nation’s economy.

So if you fix one thing, you can have a positive effect on something downstream. You see the same multiplier effect when you look at your foundation’s investments in education—and particularly in educating young women and girls. As Melinda says, the No. 1 indicator of under-5 mortality is the educational status of the mother. So fix that, and you can lift generation after generation out of poverty.

You can follow that same thread with your other major investments: trying to improve sanitation, for example, which will reduce cholera, typhoid, diarrheal disease, dysentery, and Lord knows what else. And so forth.

So now, you’ve turned in a big way to climate change—which, arguably, might be the ultimate “first mover” in a chain of problems, at least if we don’t stop it in its tracks: Fix climate change…or the world ends. If that reasoning is true, does your focus on climate change become even more dominant in this mix of causes that have grabbed your and Melinda’s attention over the years? And how do you begin to triage all these urgent demands for your time, attention, and money?

Yeah, in the foundation space—in the global health stuff—the impact per dollar is huge. We’re saving lives for less than $1,000 per life saved. And there’s this sort of market failure that, because malaria doesn’t exist in rich countries, there’s no market signal that innovators should come up with drugs and vaccines for malaria, or an overall strategy to get rid of it. The poor countries where it’s endemic don’t have the resources to solve malaria.

When I gave the first $30 million to fighting malaria, I became the biggest funder in that effort. You could say that’s a sad thing—or an opportunity to dramatically push for change. People in climate talk about carbon capture. Well, I’m the biggest funder of those companies, and that amounts to tens of millions of dollars. That includes companies like Climeworks, Carbon Engineering, and Global Thermostat. There’s like four or five companies in that carbon capture space. And fortunately, there will be more because there are several different approaches there.

Whenever I see something where the investment, if it succeeds—in terms of the societal impact per dollar—is like a thousand times return, I feel like the venture capitalist putting early money into Google or something. You know, I’m drawn in. And seeing those potential innovations succeed over time, that’s what I enjoy doing. I enjoy gathering the kind of people who can see those things and be willing to be patient. And maybe even, in some cases—like preventing or curing HIV—bet on multiple potential paths, knowing that a number will fail. But still, even if you add all that money to the different approaches, even if just one works, it’s very, very magical.

So it’s kind of an innovation mindset. There are things like improving U.S. education where, as yet, if you take broad indicators such as, “How good are U.S. students at math—or reading and writing?” or “How many kids drop out of college?” we haven’t had the kind of scale impact we’ve had on our global health work. And yet, we still believe we can make an impact. In fact, we doubled down on this effort. The idea that now more kids will actually have laptops and Internet connection, which got pushed very forward during the pandemic, has us really building a new generation of curriculum that’s very different.

So hope springs eternal even in the areas where, so far, you’d have to say the impact has been almost hard to detect. You don’t know in advance what’s going to work. And most efforts to fix a problem turn out to be harder than you think. A few—like when I put money into Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods—I would have said to you, at the outset, that “fixing meat” was as hard as creating zero-carbon steel and cement. And now, though it’s not yet solved, there’s a pathway. It’s almost like with electric cars where, as the cost goes down and the quality—in this case, of the various ways of making synthetic meat—improves, the Green Premium will go to zero. That one actually surprised me in how quickly it went.

One thing that surprised me in the book was what seemed like your belief in a natural limit to energy storage. There are some who still hold out hope for the near-infinite storage battery—or at least one with hugely expanded capacity—which would make storing energy from the sun or wind or whatever far more feasible in a grid-like way. To me, that was one heartbreaking part of the book. It’s hard to come to grips with the idea that there’s no Moore’s law for energy storage.

Yeah, the fact that Moore’s law has worked as long as it has is super mind-blowing. That software and digital stuff makes people think miracles are always possible—whereas this is more like what’s happened to gas mileage over a hundred years. You know, if Edison came back, he would look at our batteries and say, “Wow. These batteries are about four times better than my lead acid batteries. Good job.” That’s a hundred years of battery innovation.

And people get confused between batteries for electric cars and what range you get—in which just expanding range by another factor of two makes that really good—and batteries for grid storage where the aim is to collect solar energy in the summer and use it in the winter. So in that example, for that whole battery, you’re getting one benefit. One time per year you get to pull that energy out.

The cost and scale of that is so difficult. You know, we’re more than a factor of 20 away from it. I’ve lost more money on battery companies than anyone. And I’m still in, like, five different battery companies—a few directly and a few through BEV [Breakthrough Energy Ventures]. There are only three ways to solve the electric grid problem: one is a miracle in storage, the second is nuclear fission, and the third is nuclear fusion. Those are the only possibilities.

Thank you, Bill.

Thank you so much. This was fun.