1991年冬天,凯伦·林奇来到了她的姨妈米莉的病床前。凯伦·林奇家中共有兄弟姐妹四个,她并不是四人中的老大。但自从她母亲16年前去世后,28岁的林奇就成了照顾姨妈米莉的主力军。在牧师为米莉做临终祈祷的时候,林奇是唯一在场的家庭成员。在举办祈祷仪式的时候,医院的工作人员将林奇请了出去,但由于米莉姨妈激烈抗议,又只得将林奇带了回来。

在此之前的两年多时间里,林奇一直和米莉生活在马萨诸塞州的西部。从林奇12岁时起,米莉就是她的主要监护人。在米莉被诊断出乳腺癌和肺癌后,林奇放弃了在安永会计师事务所波士顿办事处的公共会计师工作,调到了离家不远的另一家安永公司办事处,以便就近照顾生病的姨妈。

米莉参加了Medicare医疗保险,所以林奇操心的并不是医疗费的问题——虽然她并不完全理解那些雪片般飞来的账单。她更关注的是癌症本身,她深入研究了癌症的机理,试图理解在姨妈身上到底发生了什么。

“所有事情都是陌生的,令人十分困惑,感觉似乎很不合逻辑。”林奇回忆道:“在和医生谈话的时候,我听不懂那些药物的术语,也听不懂出院指南。我也不知道每个处方是干什么用的。我不知道应该问什么问题,也不知道去哪寻求帮助。”

对林奇来说,米莉不仅仅是她的姨妈。林奇的母亲艾琳于1975年自杀身亡,从此以后,米莉就承担了抚养林奇兄妹4人的责任。当时的林奇兄妹实际上与孤儿无异(他们的父亲很早就抛弃了他们)。米莉本人也是一个寡妇及单身母亲,她自己也有一个孩子,工作是在一家本地工厂生产童装。米莉将全部精力投入到了这几个孩子身上,她经常告诉孩子们:“不要让你过去的经历决定你的将来。”

1991年,在米莉仍在与病魔抗争的时候,林奇找到了她在医疗保健行业的第一份工作——在信诺公司(Cigna)做医保财务报告业务。之所以选择换一个行业,一定程度上也是想更好地照顾姨妈。林奇说:“我迷失在了这个体系里,我不想让其他人也陷入一样的处境。”

30年后,58岁的林奇终于坐到了一个万众瞩目的位子上,这个位置甚至足以改变那些与米莉有同样遭遇的人的命运。今年2月1日,林奇接任了CVS Health公司的总裁兼CEO。CVS拥有9900多家连锁药店,近几年正在致力于从一家零售连锁机构转型为一家综合医疗保健公司。该公司表示,这种转型将有利于提高医疗服务对广大顾客的透明度和可获得性。

目前CVS的市值是2690亿美元,在“财富500强”企业中名列第五。在新冠肺炎疫情这场百年不遇的公共卫生危机中,CVS离它的转型目标又近了一步。2018年,CVS收购了安泰保险公司,林奇就是在这个时候加盟CVS的。去年春天,CVS任命林奇为公司的抗疫工作负责人,这项任务也为林奇问鼎CEO一职搭建了跳板。林奇可以说是临危受命,她也由此成为“财富500强”中排名最高的女性CEO。(在林奇之前,在由女性担任CEO的美国公司中,规模最大的是玛丽•巴拉领导的通用汽车公司。)

在万众瞩目之下,林奇现在拥有了一个独特的机会,来展示CVS已经具备了足够的基础能力,解决美国当前面临的最大健康挑战——通过疫苗接种,让美国实现真正的“集体免疫”。

仓促上马

虽然在疫情期间,用“好时机”一词似乎并不恰当,但是CVS现在有了为上亿美国人接种新冠疫苗的机会,这自然也就成了CVS树立正面形象的一个好时机。早在本世纪10年代初,CVS就审视了它的近万家线下实体店,并且得出了一个结论——公司发展需要新战略。我们已经进入了一个连牙膏、卫生纸甚至处方药都可以网购的时代,死守线下实体店显然已经不合时宜。CVS的解决方案是:从线下实体店向一站式医疗保健提供商转型。2014年,CVS朝着这个方向迈出了一大步,先是下架所有烟草制品,然后又推出了一个“健康中心”网络。美国的年均医疗支出大概在3.8万亿美元左右,其中慢性病的医疗支出占了90%。CVS还重新规划了它的“一分钟诊所”。以前消费者主要在“一分钟诊所”看些小病,现在这里也成了患者控制和调养慢性病的一个地方。

CVS如果能成功在新冠疫苗的普遍接种中发挥重要作用,或许将加快改变消费者对CVS的看法。比方说,以后消费者不仅可以在CVS购买胰岛素,还可以让CVS的专业医护人员协助控制自己的糖尿病。伯恩斯坦研究公司的证券分析师兰斯•威尔克斯表示:“三年前,你可能很难想象有朝一日会到CVS去看医生。如果你想改变公众的看法,同时公众也愿意接受这种服务,那么新冠疫苗的接种将在这种改变中扮演非常重要的一步。”

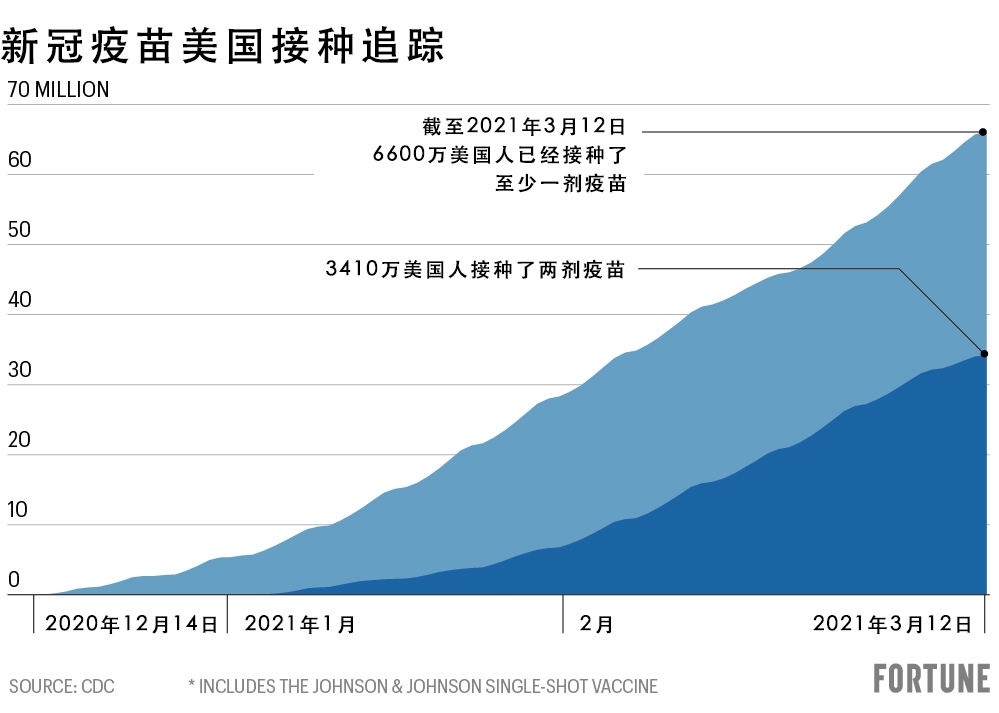

从美国目前的情况看,CVS显然会在疫苗接种工作中扮演重要的角色。该公司表示,只要疫苗供应到位,它平均每个月可以保证接种2000万到2500万人。从预计情况看,美国的整个药店零售行业每个月大约能分到9000万剂疫苗,也就是CVS有能力独立完成30%的接种。2月11日,CVS已经进入了第一阶段的接种工作,它现在正在全美29个州的大约1200个地点为符合条件的人群提供疫苗接种服务。

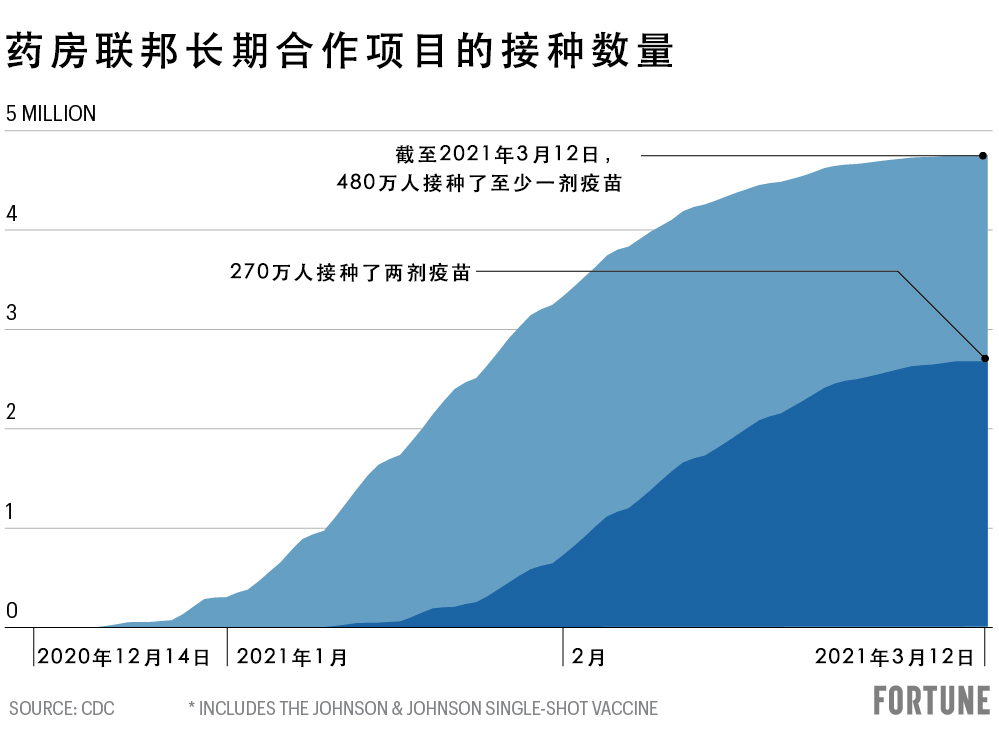

不过就像新冠病毒从来不按套路出牌一样,疫苗接种工作也经常面临计划没有变化快的问题。CVS面临的第一场真正的挑战,就是履行好它“曲速行动”中的职责。“曲速行动”是特朗普政府搞出来的疫苗计划。和竞争对手沃尔格林(Walgreens)一样,CVS在去年10月承担起了为养老院的老人和工作人员接种疫苗的工作——他们也是此次疫情中重症率和死亡率最高的高危群体。CVS加入了该计划,负责为全美7万多家养老院中的60%提供疫苗接种。为了完成这个任务,CVS开始迅速“扩编”,在已有的5万名接种人员的基础上,再次招募了1万名技术人员(该公司的员工总数将近30万人),并从12月起正式启动接种工作。

尽管做了这么多准备工作,但最终的接种情况却并不令人满意。《财富》采访了15名有关人士,包括有关州和地方的官员、医疗机构人员、公共卫生专家、疫苗专家等等,他们都对首批接种过程中暴露出来的企业和政府的官僚主义作风深感不满。虽然政府和CVS都没有就何时完成接种工作给出明确的时间表(截至发稿时,这项工作仍在进行),不过所有批评人士一致认为,目前的接种进度太慢了。约翰霍普金斯大学凯瑞商学院的运营管理学副教授戴廷龙认为,鉴于这项任务十分艰巨复杂,将如此多的任务份额分配给一家公司,这本身就是个错误。“如果各地的药店和各个独立药店都能参与进来,我们或许可以避免很多死亡和感染病例。”

当然,这种批评并不是单独针对CVS的,沃尔格林也遇到了很多同样的问题。有专家认为,由于缺乏首批接种的相关具体数据,因此我们很难衡量某一家公司是否比另一家公司做得更好。有一家养老院在采访中向《财富》报怨道,他们原本与CVS的一家药店谈好了疫苗接种,但后来对方却无故取消了。明尼苏达州奥姆斯特德县的公共卫生官员格拉汉姆·布里格斯则表示,联邦的疫苗计划只报告了州一级的接种数据,所以他并不清楚自己的辖区里谁已经完成了接种。由于缺乏可用的数据,很多批评人士都在质疑,问题究竟出在连锁药店的执行环节,还是出在政府最初的决策环节。

CVS则认为,这项工作的难点,在于这本身就是一项史无前例且极为复杂的挑战。比如接种人员必须要逐屋逐户上门接种,而且接种对象大都是卧床不起的老人,其中还有一些患有老年痴呆者,他们甚至不明白为什么要戴面具、为什么要打疫苗。CVS宣称该公司的疫苗接种是“成功的”,并表示从去年12月底到今年2月底,美国各养老院因新冠肺炎死亡的人数下降了84%,第二针疫苗的接种工作已经完成了91%。(沃尔格林则表示,它已经完成了“大部分”的指定接种工作。)截至发稿时,该计划已经接近尾声,CVS和沃尔格林两家公司已经通过这个联邦计划接种了740万剂疫苗。

作为CVS公司抗疫战略的“总设计师”,可以说,林奇对第一波疫苗接种计划负有很大责任——虽然她并没有亲自参与与联邦政府的谈判。当然,作为CEO,她必须确保项目的收尾阶段比初始阶段进行得更加平稳有力。现在,林奇已经开始展望未来了。接下来要做的,是为整个美国接种疫苗。这个挑战范围更广、难度更大,但林奇认为,她和CVS已经为此做好了准备。她说:“让我们参加这场比赛吧。”

一场耐力游戏

2019年,林奇在荷兰骑自行车旅行时,不小心摔倒在了一条鹅卵石路上。她的手、臀部和肋骨都受了伤。林奇在丈夫凯文的陪伴下飞回美国做了髋骨手术,术后髋骨必须保持固定。对林奇来说,这段漫长的住院时光也是让她集中精力思考的一个好机会。其他安泰公司的客户摔断了髋骨后,也有一样的就医体验吗?她怎样才能让自己的髋骨断得更有价值呢?

即便是住院期间,林奇也要把这段经历当成提升公司业务水平的机会。这也充分表明了她整改公司业务问题的决心。林奇曾先后在信诺、麦哲伦健康服务公司和安泰保险等公司担任高管,一向以善于解决棘手业务问题而闻名。比如00年代末期,她在信诺的牙科和眼科部门工作期间,只用了三年,就扭转了12%的亏损率,实现了4%的正增长。她的另一个长处是善于处理危机,因此公司专门让她来预测危机事件,以及组织各种灾害预案演练。据安泰保险的前任首席信息官梅格·麦卡锡称,在林奇2012年正式加盟安泰保险之前,安泰曾三次向她发出橄榄枝。(林奇自己则说是四次。)

虽然林奇不乏处理急难险重任务的勇气和手段——不论是自然灾害还是其他灾难,但毫无疑问,CVS董事会之所以选择林奇接任CEO,主要还是看中了她身上那些貌似较为“平淡”的技能。她一手操办了行业内最大的两次整合,一次是2013到2014年Medicaid和Medicare的承保商考文垂医保公司(Coventry Health Care)与安泰保险的合并,另一次就是CVS与安泰保险的700亿美元天价并购。

企业并购,尤其是医疗行业的并购,向来是一件极为复杂和残酷的事。在并购考文垂医保公司之前,安泰保险最近一次大规模并购,是上世纪90年代收购美国医疗(U.S. Healthcare),这笔交易也导致了客户和医生的怨声载道和大面积出走。为了避免再次出现这样的混乱,林奇全身心地投入到了并购工作中。在并购考文垂医保期间,她每个工作日早上8点都会召集两家公司的核心人员开会,这个做法持续了将近2年时间。而在与CVS合并的过程中,她又学到了一些在保险行业中从未遇到过的新业务,比如CVS的零售业务。而这些知识也对她最终问鼎CEO一职至关重要。

在并购过程中,林奇既顾大局也重细节的特质引起了不少人的注意。CVS的董事会成员、前任CEO拉里•梅洛表示:“她能保证运营细节的执行,而且她在促进增长和创新方面也有很出色的成绩。”如果你观察过林奇的事业轨迹,那么你大概率不会为她今天的成就而惊讶。因为以她多年从事企业运营工作,有今天的成绩是一件自然而然的事。安泰保险的CFO斯科特•沃克表示:“对她来说,这就是一场耐力的游戏,而她有很好的耐力。”沃克认识林奇已经27了,两人初识的时候,他还只是普华永道的一名审计师,而林奇已经是他的客户安泰保险公司的一名高管了。

和林奇待了一天之后,没有人会质疑她的耐力。这位CEO每天早上4点45分就会起床,5点15分开始骑动感单车,从早上7点开始打电话,然后一直工作到晚上。下班后,她会与丈夫凯文在家附近骑五六英里的自行车。(她现在住在佛罗里达州的科德角,疫情爆发前,她主要住在罗德岛的文索基特,那里也是CVS公司的总部所在地。)她的丈夫凯文表示,林奇基本上每天都在工作,“从无例外”。凯文和林奇已经结婚五年了。不过两人第一见面的时候,还都是十八九岁的年纪。当时两人都在科德角的一家24小时餐厅里打工,一个是服务员,另一个是厨师,两人谈了一段短暂的夏日恋情。(他们是在2004年重新联系上的,当时凯文正在为HCA医院谈一份信诺的合同,他发现谈判的对手竟然是林奇,于是他给她打了个电话。搞笑的是,林奇竟然让他先和她的助理一起吃午餐,好审查他为什么要联系她。)凯文还讲了一件趣事,有一次林奇正在一个项目上忙得焦头烂额,她居然对丈夫说:“你昨天下午跟我待了整整三天。”

“卸下铠甲”

但是,那些很早就与林奇共事的人,除了了解她的职业道德和她永不疲倦的工作状态之外,对她本人却并不十分了解。(林奇有一个助理已经跟了她7年了,有一次凯文向助理提到林奇有三个兄弟姐妹,这个助理竟然还是头一次听说自己的老板有兄弟姐妹。)在麦哲伦健康服务公司工作期间,林奇的员工甚至不知道她的母亲艾琳早已死于自杀。林奇表示:“我很尴尬,我觉得人们可能会为此对我评头论足,他们可能已经这样做了。”

这种情况直到2015年才有所改变,这一年,林奇当上了安泰保险的总裁。她表示,直到坐上这个位子,她的看法才真正有所改变。她终于拥有了足够高的地位,可以卸下自我防护了。“我觉得自己就像卸下了铠甲,”林奇回忆道:“我做回了真正的自己,我不再隐瞒任何事了。”

虽然林奇认为,自己当初之所以选择了医疗行业,很大程度是由于姨妈米莉的病,但在她童年时期,她曾多次目睹母亲受精神疾病折磨的样子,这段经历也很大程度影响了她的工作方式。这么多年来,林奇一直不愿谈论母亲的死——不仅在公众面前,就是私下里也是如此。她担心别人对她评头论足,认为她是一个没有父母、“一事无成”的孩子。早在12岁的时候,林奇就对美国医疗体系的失败有了切肤之痛。母亲在去世前,曾与精神疾病做了多年的斗争,但她并非总能及时接受所需的治疗。由于母亲去世时林奇的年纪还小,所以这件事并未像姨妈米莉去世前的经历一样,让她深刻改变对美国医疗体系的看法。但当她开始在医疗行业崭露头角时,当她开始思考美国医疗制度哪些最迫切地需要改革时,母亲的形象就又会在她心头浮现。

以前,与林奇共过事的人大都认为林奇是一个善解人意、愿意倾听的人。不过他们也表示,林奇看起来很有防备感,似乎不愿意过多说自己的事。但现在不同了。现在林奇比美国企业界的任何高管都愿意谈论那些最艰难的话题。她愿意将母亲患有精神疾的经历说出来。(“她有病”,林奇在谈及母亲时说:“我并不真正了解她。”)她也愿意讨论为工作做出的牺牲,并提到了之前离婚和失去朋友的经历。(“友谊、爱情都需要时间去陪伴,如果你的工作像我一样忙碌,那么我要告诉你,我可能已经在这个过程中失去了一些东西。”)她也愿意谈论自己为什么决定不要孩子,一方面是因为她全心全意投身于自己的事业,另一方面则是因为自己在孩提时代失去了唯一的父母,由此带来了终身的心理创伤。(“我自己经历过那种痛苦,我不想让别人也要经历同样的痛苦。”)

乔纳森•梅休是CVS公司负责企业转型的高级副总裁,他与林奇相识已经20年了,当时两人都在信诺公司工作。他表示:“这段经历使她变得坚强和刚硬——包括她对自己的预期。但对其他人来说,这段经历也使她变得更有同情心,更以人为本、以消费者为中心。”

出于以上原因,林奇一直高度关注医保公司(现在是医保服务提供商和各大药店)对精神病患者的做法。她讲述了发生在麦哲伦健康服务公司的一个故事:有一位大学生患有饮食失调症,2010年,麦哲伦公司曾为是否要报销他的治疗费用而发生过分歧,但林奇最终还是拍板报销,并亲自给这个学生打了电话,鼓励他接受治疗。(林奇表示,这个学生已经康复了,现在是一名教师。)可以想象,林奇在打这通电话时,心里肯定想到了自己那位长期没有受到应有治疗的母亲。

扎根于地方

林奇之所以要讲出自己的故事,也是为了与员工建立信任。随着CVS在疫苗接种大战中扮演愈发重要的角色,公司也迫切需要与顾客群体建立同样的信任感。

“药剂师可以提供重要的慰藉和信心。” 前陆军药剂师约翰·格拉本斯坦上校说。格拉本斯坦1996年编写了美国药剂师协会的免疫培训项目教材,该项目至今仍在培训药剂师如何接种疫苗。

在90年代中期以前,美国的药剂师并不会定期给病人接种任何疫苗,因为这通常是医生和护士的工作。1994年,华盛顿州率先在美国开展了药剂师接种疫苗的培训。两年后,格拉本斯坦写了他的培训手册,指导药剂师任务从正确的位置、角度、深度下针,通过上臂注射,完成疫苗接种任务。从2000年开始,在药店里接种疫苗,尤其是流感疫苗,已经是一件司空见惯的事了。现如今,有3500万美国人会在药店里接种流感疫苗。

很多美国人一年才会去看一次医生,但每周都要去当地药店好几次,更不用说周末和逢年过节。虽然新冠疫苗已经以创纪录的速度研发出来了,但越是这样,很多美国人越是心存疑虑,不敢或不愿到药店接种。据CVS统计,美国养老院里约有60%的工作人员拒绝接种新冠疫苗。格拉本斯坦表示:“有些人对接种疫苗的倡议根本不做任何反应。而药剂师则可以问同一个人两次、三次甚至四次,直到他们最终同意。”

2021年2月12日,东波士顿的一名CVS药店技术人员莱斯利·卡内乔(左)在接种新冠疫苗后,与当地护士克莱尔·卡拉斯交谈。据CVS公司证实,根据公司与联邦政府最新达成的协议,从2月12日起,一些CVS药店已经开始在罗德岛和马萨诸塞州的部分指定地点,为符合条件的人接种新冠疫苗。图片来源:Erin Clark—《波士顿环球报》/Getty Images

2021年2月12日,东波士顿的一名CVS药店技术人员莱斯利·卡内乔(左)在接种新冠疫苗后,与当地护士克莱尔·卡拉斯交谈。据CVS公司证实,根据公司与联邦政府最新达成的协议,从2月12日起,一些CVS药店已经开始在罗德岛和马萨诸塞州的部分指定地点,为符合条件的人接种新冠疫苗。图片来源:Erin Clark—《波士顿环球报》/Getty Images

普通人的生活离不开一家当地的药房,这也是很多专家对CVS的大规模接种能力有信心的原因。顾客的定期造访,意味着药房可以拿到顾客的信息,从而使他们找到高优先级的接种对象。“药剂师知道哪些人有慢性病,他们能列出本地的糖尿病和心脏病患者的名单,因为他们知道哪些人买过胰岛素、二甲双胍和地高辛。” 格拉本斯坦说。凭借数字化的基础设施,CVS还能让患者开展在线预约,并且与患者持续保持联系。任何一个CVS的顾客只要收到了短信提醒,就知道自己该去扎第二针了。

但新冠病毒毕竟不是流感病毒,新冠疫苗也不是流感疫苗。CVS必须在药店里设置一个专门空间,对刚接种完疫苗的顾客进行15分钟的医学观察。这也是新冠疫苗的特殊要求,因为美国的新冠疫苗确实出现了少量过敏反应。如果接种需求量还像前几个月那么高,CVS还要确保在线预约功能正常运转,并且确保顾客能够预约到位子。药剂师也必须妥善做好安排计划,这样才不会浪费额外的疫苗,或者导致对温度极为敏感的新冠疫苗发生变质。

对CVS公司来说,大规模接种新冠疫苗,既给公司带来了机遇,也带来了风险。如果由于某种原因,它的疫苗大规模接种没有顺畅推进下去,那么这种负面印象将会伴随消费者很多年。

美国企业界最受关注女性

通常来说,作为CVS公司的CEO,林奇不会在一项疫苗计划上花费太多时间,但新冠疫苗就不同了。林奇认为,这次疫苗接种工作预计将耗费她的大量精力。CVS公司的首席医官特罗因·布伦南是该公司疫苗接种计划的负责人,在过去一年里,林奇与布伦南一直在并肩工作,并且把她丰富的运营知识运用到了公司的抗疫战略里。除了向公众开放接种,他们还要保护CVS的零售员工的健康和安全。另外,他们还要设立4800个新冠病毒检测点,解决检测结果周转过慢等问题,同时还要确保其他药品和必要医疗器材的充足供应。

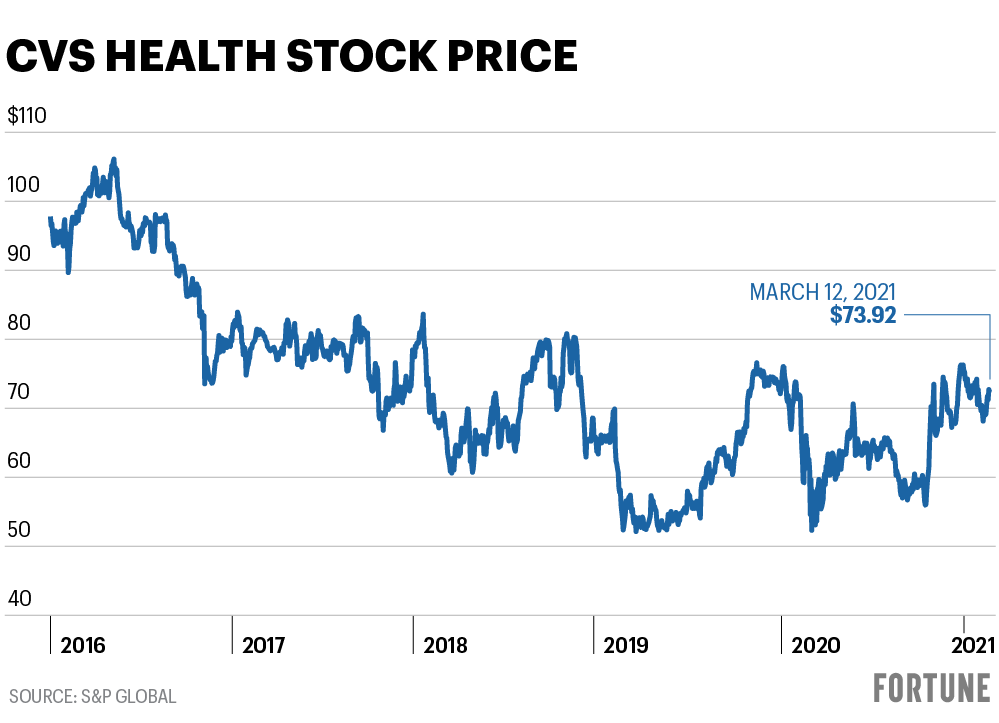

不过像我们中的很多人一样,林奇已经把眼光投向了疫情以后。她已经喊出了“进军100”的口号——即将公司股价从去年的65美元提高到100美元。(CVS的股价在2018年并购安泰时遭遇重创,理由是华尔街认为它的收购价过高。不过从那时起,CVS的股价已经缓慢回升。)林奇还计划推进CVS医疗服务的数字化,以及推出专家数字挂号等服务,这些都超过了疫情的范畴。她还打算加快推进“替代医疗点”计划,也就是用CVS的门店取代医院的一部分职能。而在这个过程中,她必须巩固CSV在消费者和投资者眼中的新形象。林奇表示:“当人们想到健康问题时,我希望他们想到的是CVS Health。”

林奇也是当前美国商界最受关注的女性之一。对这一点最有感触的,当属CVS价值910亿美元的零售药店部门负责人、曾于2017年至2019年担任家居品牌Crate & Barrel首席执行官的尼拉•蒙哥马利。她表示:“地位最高的女性——在任何一个时间段,总会有这么一个人吧?在我事业的早期阶段,我常常以为,自己只是开始承担起另一项重要工作,跟别人没什么区别。但随着时间的推移,你会发现并非如此。如果你是‘第一人’,你就要承担更多的压力,受到更多的审视。”

但林奇并不孤单。就在她正式就任CEO之前的几天,CVS的主要竞争对手沃博联宣布,前沃尔玛和星巴克高管罗莎琳德·布鲁尔将担任其下任CEO。沃博联的当前市值为1400亿美元,在“财富500强”排名第19位。(布鲁尔也将成为目前“财富500强”企业中唯二的黑人女性CEO之一。)

就像林奇反复强调的那样,医疗是一件很私人的事。在我就她失去两名亲人的事发问之前,我提到我26岁时也失去了父母。在采访结束后,林奇匆匆赶往下一个活动,这时她已经迟到了——她很讨厌迟到。但她还是在电话里对我说:“20多岁的时候失去父母,我理解这种感觉——如果你愿意谈谈的话。”

早在28岁的时候,还在从事财务工作的林奇就树立了一个雄心勃勃的目标,要从内部改革美国的医疗体系。直到今天,这依然是她的目标,而且她依然雄心不减。但如果真的有人能实现这个目标,那么这个领导者肯定是一个了解什么东西才真正重要的人。

“我们每一天有机会影响人们的生活,我不会对此等闲视之,”林奇说:“毕竟我经历过,对吧?”(财富中文网)

译者:朴成奎

1991年冬天,凯伦·林奇来到了她的姨妈米莉的病床前。凯伦·林奇家中共有兄弟姐妹四个,她并不是四人中的老大。但自从她母亲16年前去世后,28岁的林奇就成了照顾姨妈米莉的主力军。在牧师为米莉做临终祈祷的时候,林奇是唯一在场的家庭成员。在举办祈祷仪式的时候,医院的工作人员将林奇请了出去,但由于米莉姨妈激烈抗议,又只得将林奇带了回来。

在此之前的两年多时间里,林奇一直和米莉生活在马萨诸塞州的西部。从林奇12岁时起,米莉就是她的主要监护人。在米莉被诊断出乳腺癌和肺癌后,林奇放弃了在安永会计师事务所波士顿办事处的公共会计师工作,调到了离家不远的另一家安永公司办事处,以便就近照顾生病的姨妈。

米莉参加了Medicare医疗保险,所以林奇操心的并不是医疗费的问题——虽然她并不完全理解那些雪片般飞来的账单。她更关注的是癌症本身,她深入研究了癌症的机理,试图理解在姨妈身上到底发生了什么。

“所有事情都是陌生的,令人十分困惑,感觉似乎很不合逻辑。”林奇回忆道:“在和医生谈话的时候,我听不懂那些药物的术语,也听不懂出院指南。我也不知道每个处方是干什么用的。我不知道应该问什么问题,也不知道去哪寻求帮助。”

对林奇来说,米莉不仅仅是她的姨妈。林奇的母亲艾琳于1975年自杀身亡,从此以后,米莉就承担了抚养林奇兄妹4人的责任。当时的林奇兄妹实际上与孤儿无异(他们的父亲很早就抛弃了他们)。米莉本人也是一个寡妇及单身母亲,她自己也有一个孩子,工作是在一家本地工厂生产童装。米莉将全部精力投入到了这几个孩子身上,她经常告诉孩子们:“不要让你过去的经历决定你的将来。”

1991年,在米莉仍在与病魔抗争的时候,林奇找到了她在医疗保健行业的第一份工作——在信诺公司(Cigna)做医保财务报告业务。之所以选择换一个行业,一定程度上也是想更好地照顾姨妈。林奇说:“我迷失在了这个体系里,我不想让其他人也陷入一样的处境。”

30年后,58岁的林奇终于坐到了一个万众瞩目的位子上,这个位置甚至足以改变那些与米莉有同样遭遇的人的命运。今年2月1日,林奇接任了CVS Health公司的总裁兼CEO。CVS拥有9900多家连锁药店,近几年正在致力于从一家零售连锁机构转型为一家综合医疗保健公司。该公司表示,这种转型将有利于提高医疗服务对广大顾客的透明度和可获得性。

目前CVS的市值是2690亿美元,在“财富500强”企业中名列第五。在新冠肺炎疫情这场百年不遇的公共卫生危机中,CVS离它的转型目标又近了一步。2018年,CVS收购了安泰保险公司,林奇就是在这个时候加盟CVS的。去年春天,CVS任命林奇为公司的抗疫工作负责人,这项任务也为林奇问鼎CEO一职搭建了跳板。林奇可以说是临危受命,她也由此成为“财富500强”中排名最高的女性CEO。(在林奇之前,在由女性担任CEO的美国公司中,规模最大的是玛丽•巴拉领导的通用汽车公司。)

在万众瞩目之下,林奇现在拥有了一个独特的机会,来展示CVS已经具备了足够的基础能力,解决美国当前面临的最大健康挑战——通过疫苗接种,让美国实现真正的“集体免疫”。

仓促上马

虽然在疫情期间,用“好时机”一词似乎并不恰当,但是CVS现在有了为上亿美国人接种新冠疫苗的机会,这自然也就成了CVS树立正面形象的一个好时机。早在本世纪10年代初,CVS就审视了它的近万家线下实体店,并且得出了一个结论——公司发展需要新战略。我们已经进入了一个连牙膏、卫生纸甚至处方药都可以网购的时代,死守线下实体店显然已经不合时宜。CVS的解决方案是:从线下实体店向一站式医疗保健提供商转型。2014年,CVS朝着这个方向迈出了一大步,先是下架所有烟草制品,然后又推出了一个“健康中心”网络。美国的年均医疗支出大概在3.8万亿美元左右,其中慢性病的医疗支出占了90%。CVS还重新规划了它的“一分钟诊所”。以前消费者主要在“一分钟诊所”看些小病,现在这里也成了患者控制和调养慢性病的一个地方。

CVS如果能成功在新冠疫苗的普遍接种中发挥重要作用,或许将加快改变消费者对CVS的看法。比方说,以后消费者不仅可以在CVS购买胰岛素,还可以让CVS的专业医护人员协助控制自己的糖尿病。伯恩斯坦研究公司的证券分析师兰斯•威尔克斯表示:“三年前,你可能很难想象有朝一日会到CVS去看医生。如果你想改变公众的看法,同时公众也愿意接受这种服务,那么新冠疫苗的接种将在这种改变中扮演非常重要的一步。”

从美国目前的情况看,CVS显然会在疫苗接种工作中扮演重要的角色。该公司表示,只要疫苗供应到位,它平均每个月可以保证接种2000万到2500万人。从预计情况看,美国的整个药店零售行业每个月大约能分到9000万剂疫苗,也就是CVS有能力独立完成30%的接种。2月11日,CVS已经进入了第一阶段的接种工作,它现在正在全美29个州的大约1200个地点为符合条件的人群提供疫苗接种服务。

不过就像新冠病毒从来不按套路出牌一样,疫苗接种工作也经常面临计划没有变化快的问题。CVS面临的第一场真正的挑战,就是履行好它“曲速行动”中的职责。“曲速行动”是特朗普政府搞出来的疫苗计划。和竞争对手沃尔格林(Walgreens)一样,CVS在去年10月承担起了为养老院的老人和工作人员接种疫苗的工作——他们也是此次疫情中重症率和死亡率最高的高危群体。CVS加入了该计划,负责为全美7万多家养老院中的60%提供疫苗接种。为了完成这个任务,CVS开始迅速“扩编”,在已有的5万名接种人员的基础上,再次招募了1万名技术人员(该公司的员工总数将近30万人),并从12月起正式启动接种工作。

尽管做了这么多准备工作,但最终的接种情况却并不令人满意。《财富》采访了15名有关人士,包括有关州和地方的官员、医疗机构人员、公共卫生专家、疫苗专家等等,他们都对首批接种过程中暴露出来的企业和政府的官僚主义作风深感不满。虽然政府和CVS都没有就何时完成接种工作给出明确的时间表(截至发稿时,这项工作仍在进行),不过所有批评人士一致认为,目前的接种进度太慢了。约翰霍普金斯大学凯瑞商学院的运营管理学副教授戴廷龙认为,鉴于这项任务十分艰巨复杂,将如此多的任务份额分配给一家公司,这本身就是个错误。“如果各地的药店和各个独立药店都能参与进来,我们或许可以避免很多死亡和感染病例。”

当然,这种批评并不是单独针对CVS的,沃尔格林也遇到了很多同样的问题。有专家认为,由于缺乏首批接种的相关具体数据,因此我们很难衡量某一家公司是否比另一家公司做得更好。有一家养老院在采访中向《财富》报怨道,他们原本与CVS的一家药店谈好了疫苗接种,但后来对方却无故取消了。明尼苏达州奥姆斯特德县的公共卫生官员格拉汉姆·布里格斯则表示,联邦的疫苗计划只报告了州一级的接种数据,所以他并不清楚自己的辖区里谁已经完成了接种。由于缺乏可用的数据,很多批评人士都在质疑,问题究竟出在连锁药店的执行环节,还是出在政府最初的决策环节。

CVS则认为,这项工作的难点,在于这本身就是一项史无前例且极为复杂的挑战。比如接种人员必须要逐屋逐户上门接种,而且接种对象大都是卧床不起的老人,其中还有一些患有老年痴呆者,他们甚至不明白为什么要戴面具、为什么要打疫苗。CVS宣称该公司的疫苗接种是“成功的”,并表示从去年12月底到今年2月底,美国各养老院因新冠肺炎死亡的人数下降了84%,第二针疫苗的接种工作已经完成了91%。(沃尔格林则表示,它已经完成了“大部分”的指定接种工作。)截至发稿时,该计划已经接近尾声,CVS和沃尔格林两家公司已经通过这个联邦计划接种了740万剂疫苗。

作为CVS公司抗疫战略的“总设计师”,可以说,林奇对第一波疫苗接种计划负有很大责任——虽然她并没有亲自参与与联邦政府的谈判。当然,作为CEO,她必须确保项目的收尾阶段比初始阶段进行得更加平稳有力。现在,林奇已经开始展望未来了。接下来要做的,是为整个美国接种疫苗。这个挑战范围更广、难度更大,但林奇认为,她和CVS已经为此做好了准备。她说:“让我们参加这场比赛吧。”

一场耐力游戏

2019年,林奇在荷兰骑自行车旅行时,不小心摔倒在了一条鹅卵石路上。她的手、臀部和肋骨都受了伤。林奇在丈夫凯文的陪伴下飞回美国做了髋骨手术,术后髋骨必须保持固定。对林奇来说,这段漫长的住院时光也是让她集中精力思考的一个好机会。其他安泰公司的客户摔断了髋骨后,也有一样的就医体验吗?她怎样才能让自己的髋骨断得更有价值呢?

即便是住院期间,林奇也要把这段经历当成提升公司业务水平的机会。这也充分表明了她整改公司业务问题的决心。林奇曾先后在信诺、麦哲伦健康服务公司和安泰保险等公司担任高管,一向以善于解决棘手业务问题而闻名。比如00年代末期,她在信诺的牙科和眼科部门工作期间,只用了三年,就扭转了12%的亏损率,实现了4%的正增长。她的另一个长处是善于处理危机,因此公司专门让她来预测危机事件,以及组织各种灾害预案演练。据安泰保险的前任首席信息官梅格·麦卡锡称,在林奇2012年正式加盟安泰保险之前,安泰曾三次向她发出橄榄枝。(林奇自己则说是四次。)

虽然林奇不乏处理急难险重任务的勇气和手段——不论是自然灾害还是其他灾难,但毫无疑问,CVS董事会之所以选择林奇接任CEO,主要还是看中了她身上那些貌似较为“平淡”的技能。她一手操办了行业内最大的两次整合,一次是2013到2014年Medicaid和Medicare的承保商考文垂医保公司(Coventry Health Care)与安泰保险的合并,另一次就是CVS与安泰保险的700亿美元天价并购。

企业并购,尤其是医疗行业的并购,向来是一件极为复杂和残酷的事。在并购考文垂医保公司之前,安泰保险最近一次大规模并购,是上世纪90年代收购美国医疗(U.S. Healthcare),这笔交易也导致了客户和医生的怨声载道和大面积出走。为了避免再次出现这样的混乱,林奇全身心地投入到了并购工作中。在并购考文垂医保期间,她每个工作日早上8点都会召集两家公司的核心人员开会,这个做法持续了将近2年时间。而在与CVS合并的过程中,她又学到了一些在保险行业中从未遇到过的新业务,比如CVS的零售业务。而这些知识也对她最终问鼎CEO一职至关重要。

在并购过程中,林奇既顾大局也重细节的特质引起了不少人的注意。CVS的董事会成员、前任CEO拉里•梅洛表示:“她能保证运营细节的执行,而且她在促进增长和创新方面也有很出色的成绩。”如果你观察过林奇的事业轨迹,那么你大概率不会为她今天的成就而惊讶。因为以她多年从事企业运营工作,有今天的成绩是一件自然而然的事。安泰保险的CFO斯科特•沃克表示:“对她来说,这就是一场耐力的游戏,而她有很好的耐力。”沃克认识林奇已经27了,两人初识的时候,他还只是普华永道的一名审计师,而林奇已经是他的客户安泰保险公司的一名高管了。

和林奇待了一天之后,没有人会质疑她的耐力。这位CEO每天早上4点45分就会起床,5点15分开始骑动感单车,从早上7点开始打电话,然后一直工作到晚上。下班后,她会与丈夫凯文在家附近骑五六英里的自行车。(她现在住在佛罗里达州的科德角,疫情爆发前,她主要住在罗德岛的文索基特,那里也是CVS公司的总部所在地。)她的丈夫凯文表示,林奇基本上每天都在工作,“从无例外”。凯文和林奇已经结婚五年了。不过两人第一见面的时候,还都是十八九岁的年纪。当时两人都在科德角的一家24小时餐厅里打工,一个是服务员,另一个是厨师,两人谈了一段短暂的夏日恋情。(他们是在2004年重新联系上的,当时凯文正在为HCA医院谈一份信诺的合同,他发现谈判的对手竟然是林奇,于是他给她打了个电话。搞笑的是,林奇竟然让他先和她的助理一起吃午餐,好审查他为什么要联系她。)凯文还讲了一件趣事,有一次林奇正在一个项目上忙得焦头烂额,她居然对丈夫说:“你昨天下午跟我待了整整三天。”

“卸下铠甲”

但是,那些很早就与林奇共事的人,除了了解她的职业道德和她永不疲倦的工作状态之外,对她本人却并不十分了解。(林奇有一个助理已经跟了她7年了,有一次凯文向助理提到林奇有三个兄弟姐妹,这个助理竟然还是头一次听说自己的老板有兄弟姐妹。)在麦哲伦健康服务公司工作期间,林奇的员工甚至不知道她的母亲艾琳早已死于自杀。林奇表示:“我很尴尬,我觉得人们可能会为此对我评头论足,他们可能已经这样做了。”

这种情况直到2015年才有所改变,这一年,林奇当上了安泰保险的总裁。她表示,直到坐上这个位子,她的看法才真正有所改变。她终于拥有了足够高的地位,可以卸下自我防护了。“我觉得自己就像卸下了铠甲,”林奇回忆道:“我做回了真正的自己,我不再隐瞒任何事了。”

虽然林奇认为,自己当初之所以选择了医疗行业,很大程度是由于姨妈米莉的病,但在她童年时期,她曾多次目睹母亲受精神疾病折磨的样子,这段经历也很大程度影响了她的工作方式。这么多年来,林奇一直不愿谈论母亲的死——不仅在公众面前,就是私下里也是如此。她担心别人对她评头论足,认为她是一个没有父母、“一事无成”的孩子。早在12岁的时候,林奇就对美国医疗体系的失败有了切肤之痛。母亲在去世前,曾与精神疾病做了多年的斗争,但她并非总能及时接受所需的治疗。由于母亲去世时林奇的年纪还小,所以这件事并未像姨妈米莉去世前的经历一样,让她深刻改变对美国医疗体系的看法。但当她开始在医疗行业崭露头角时,当她开始思考美国医疗制度哪些最迫切地需要改革时,母亲的形象就又会在她心头浮现。

以前,与林奇共过事的人大都认为林奇是一个善解人意、愿意倾听的人。不过他们也表示,林奇看起来很有防备感,似乎不愿意过多说自己的事。但现在不同了。现在林奇比美国企业界的任何高管都愿意谈论那些最艰难的话题。她愿意将母亲患有精神疾的经历说出来。(“她有病”,林奇在谈及母亲时说:“我并不真正了解她。”)她也愿意讨论为工作做出的牺牲,并提到了之前离婚和失去朋友的经历。(“友谊、爱情都需要时间去陪伴,如果你的工作像我一样忙碌,那么我要告诉你,我可能已经在这个过程中失去了一些东西。”)她也愿意谈论自己为什么决定不要孩子,一方面是因为她全心全意投身于自己的事业,另一方面则是因为自己在孩提时代失去了唯一的父母,由此带来了终身的心理创伤。(“我自己经历过那种痛苦,我不想让别人也要经历同样的痛苦。”)

乔纳森•梅休是CVS公司负责企业转型的高级副总裁,他与林奇相识已经20年了,当时两人都在信诺公司工作。他表示:“这段经历使她变得坚强和刚硬——包括她对自己的预期。但对其他人来说,这段经历也使她变得更有同情心,更以人为本、以消费者为中心。”

出于以上原因,林奇一直高度关注医保公司(现在是医保服务提供商和各大药店)对精神病患者的做法。她讲述了发生在麦哲伦健康服务公司的一个故事:有一位大学生患有饮食失调症,2010年,麦哲伦公司曾为是否要报销他的治疗费用而发生过分歧,但林奇最终还是拍板报销,并亲自给这个学生打了电话,鼓励他接受治疗。(林奇表示,这个学生已经康复了,现在是一名教师。)可以想象,林奇在打这通电话时,心里肯定想到了自己那位长期没有受到应有治疗的母亲。

扎根于地方

林奇之所以要讲出自己的故事,也是为了与员工建立信任。随着CVS在疫苗接种大战中扮演愈发重要的角色,公司也迫切需要与顾客群体建立同样的信任感。

“药剂师可以提供重要的慰藉和信心。” 前陆军药剂师约翰·格拉本斯坦上校说。格拉本斯坦1996年编写了美国药剂师协会的免疫培训项目教材,该项目至今仍在培训药剂师如何接种疫苗。

在90年代中期以前,美国的药剂师并不会定期给病人接种任何疫苗,因为这通常是医生和护士的工作。1994年,华盛顿州率先在美国开展了药剂师接种疫苗的培训。两年后,格拉本斯坦写了他的培训手册,指导药剂师任务从正确的位置、角度、深度下针,通过上臂注射,完成疫苗接种任务。从2000年开始,在药店里接种疫苗,尤其是流感疫苗,已经是一件司空见惯的事了。现如今,有3500万美国人会在药店里接种流感疫苗。

很多美国人一年才会去看一次医生,但每周都要去当地药店好几次,更不用说周末和逢年过节。虽然新冠疫苗已经以创纪录的速度研发出来了,但越是这样,很多美国人越是心存疑虑,不敢或不愿到药店接种。据CVS统计,美国养老院里约有60%的工作人员拒绝接种新冠疫苗。格拉本斯坦表示:“有些人对接种疫苗的倡议根本不做任何反应。而药剂师则可以问同一个人两次、三次甚至四次,直到他们最终同意。”

普通人的生活离不开一家当地的药房,这也是很多专家对CVS的大规模接种能力有信心的原因。顾客的定期造访,意味着药房可以拿到顾客的信息,从而使他们找到高优先级的接种对象。“药剂师知道哪些人有慢性病,他们能列出本地的糖尿病和心脏病患者的名单,因为他们知道哪些人买过胰岛素、二甲双胍和地高辛。” 格拉本斯坦说。凭借数字化的基础设施,CVS还能让患者开展在线预约,并且与患者持续保持联系。任何一个CVS的顾客只要收到了短信提醒,就知道自己该去扎第二针了。

但新冠病毒毕竟不是流感病毒,新冠疫苗也不是流感疫苗。CVS必须在药店里设置一个专门空间,对刚接种完疫苗的顾客进行15分钟的医学观察。这也是新冠疫苗的特殊要求,因为美国的新冠疫苗确实出现了少量过敏反应。如果接种需求量还像前几个月那么高,CVS还要确保在线预约功能正常运转,并且确保顾客能够预约到位子。药剂师也必须妥善做好安排计划,这样才不会浪费额外的疫苗,或者导致对温度极为敏感的新冠疫苗发生变质。

对CVS公司来说,大规模接种新冠疫苗,既给公司带来了机遇,也带来了风险。如果由于某种原因,它的疫苗大规模接种没有顺畅推进下去,那么这种负面印象将会伴随消费者很多年。

美国企业界最受关注女性

通常来说,作为CVS公司的CEO,林奇不会在一项疫苗计划上花费太多时间,但新冠疫苗就不同了。林奇认为,这次疫苗接种工作预计将耗费她的大量精力。CVS公司的首席医官特罗因·布伦南是该公司疫苗接种计划的负责人,在过去一年里,林奇与布伦南一直在并肩工作,并且把她丰富的运营知识运用到了公司的抗疫战略里。除了向公众开放接种,他们还要保护CVS的零售员工的健康和安全。另外,他们还要设立4800个新冠病毒检测点,解决检测结果周转过慢等问题,同时还要确保其他药品和必要医疗器材的充足供应。

不过像我们中的很多人一样,林奇已经把眼光投向了疫情以后。她已经喊出了“进军100”的口号——即将公司股价从去年的65美元提高到100美元。(CVS的股价在2018年并购安泰时遭遇重创,理由是华尔街认为它的收购价过高。不过从那时起,CVS的股价已经缓慢回升。)林奇还计划推进CVS医疗服务的数字化,以及推出专家数字挂号等服务,这些都超过了疫情的范畴。她还打算加快推进“替代医疗点”计划,也就是用CVS的门店取代医院的一部分职能。而在这个过程中,她必须巩固CSV在消费者和投资者眼中的新形象。林奇表示:“当人们想到健康问题时,我希望他们想到的是CVS Health。”

林奇也是当前美国商界最受关注的女性之一。对这一点最有感触的,当属CVS价值910亿美元的零售药店部门负责人、曾于2017年至2019年担任家居品牌Crate & Barrel首席执行官的尼拉•蒙哥马利。她表示:“地位最高的女性——在任何一个时间段,总会有这么一个人吧?在我事业的早期阶段,我常常以为,自己只是开始承担起另一项重要工作,跟别人没什么区别。但随着时间的推移,你会发现并非如此。如果你是‘第一人’,你就要承担更多的压力,受到更多的审视。”

但林奇并不孤单。就在她正式就任CEO之前的几天,CVS的主要竞争对手沃博联宣布,前沃尔玛和星巴克高管罗莎琳德·布鲁尔将担任其下任CEO。沃博联的当前市值为1400亿美元,在“财富500强”排名第19位。(布鲁尔也将成为目前“财富500强”企业中唯二的黑人女性CEO之一。)

就像林奇反复强调的那样,医疗是一件很私人的事。在我就她失去两名亲人的事发问之前,我提到我26岁时也失去了父母。在采访结束后,林奇匆匆赶往下一个活动,这时她已经迟到了——她很讨厌迟到。但她还是在电话里对我说:“20多岁的时候失去父母,我理解这种感觉——如果你愿意谈谈的话。”

早在28岁的时候,还在从事财务工作的林奇就树立了一个雄心勃勃的目标,要从内部改革美国的医疗体系。直到今天,这依然是她的目标,而且她依然雄心不减。但如果真的有人能实现这个目标,那么这个领导者肯定是一个了解什么东西才真正重要的人。

“我们每一天有机会影响人们的生活,我不会对此等闲视之,”林奇说:“毕竟我经历过,对吧?”(财富中文网)

译者:朴成奎

In the winter of 1991, Karen Lynch sat by her Aunt Millie’s hospital bed. Lynch wasn’t the eldest of her family’s four siblings, but in the 16 years since their mother’s death, the 28-year-old had become Millie’s primary caretaker. When a priest arrived to deliver Millie’s last rites, Lynch was the only family member present. Hospital staff escorted her out of the room for the ceremony but brought her back in when Millie, fiery to her last days, protested.

For more than two years, Lynch had lived in western Massachusetts with Millie, the woman who had raised her since she was 12 years old. Lynch left behind her life as a public accountant at Ernst & Young’s Boston office after Millie’s diagnosis, getting transferred to an office closer to home to be with her aunt as she saw doctor after doctor about her progressing breast and lung cancer.

Millie was covered by Medicare, so it wasn’t medical expenses that kept Lynch up late at night—although she didn’t fully understand the bills that kept streaming in. Instead, she obsessed over the cancer itself, researching the disease in an attempt to grasp what was happening to her aunt.

“Everything was unfamiliar. It was confusing, it wasn’t logical,” Lynch recalls. “When her doctors would talk to me, I wouldn’t understand the medication terminology or the discharge instructions. I didn’t know what each prescription was for. And I didn’t know what kinds of questions to ask or where to get help.”

Millie was more than an aunt to Lynch. When Lynch’s mother, Irene, died by suicide in 1975, Millie took in and raised Lynch and her three siblings, who were, in effect, orphaned (their father left when the children were young). A widow and single mother of one who spent her days in a local factory making baby clothes for the brand Carter’s, Millie dedicated herself to her nieces and nephew, Lynch says, reminding them: “Don’t let your past experiences dictate your future.”

In 1991, with Millie still battling her illness, Lynch took her first job in the health care sector, a position in health plan financial reporting at Cigna. The move was, in part, inspired by her struggle to care for her aunt. “I was lost in the system,” says Lynch. “I didn’t want other people to not know how to navigate it.”

Three decades later, Lynch, now 58, finds herself in a rare position to change the experiences of some of those who are struggling in much the same way she was when she sat at Millie’s side. On Feb. 1, she took over as president and CEO of CVS Health, a chain of more than 9,900 pharmacy locations that is in the midst of a multiyear effort to transform itself from retailer to health care company—a change it says will make care more transparent and accessible to its massive customer base.

The $269 billion Goliath—ranked No. 5 in the Fortune 500—is getting closer to achieving its goal amid the coronavirus pandemic, the most serious public health crisis in 100 years. Lynch joined the company when CVS acquired Aetna in 2018. Last spring, CVS tapped her to manage its COVID response, a role that proved to be a stepping-stone to the top job. She takes the lead at a critical moment—and one that comes with the extra weight of becoming the most high-ranking female CEO ever to appear in the Fortune 500. (Until Lynch became CEO, the largest U.S. company run by a woman was General Motors, led by Mary Barra.)

As Lynch walks into that glaring spotlight, she has the unique opportunity to show that CVS has created an infrastructure capable of meeting one of the biggest health challenges of the century: vaccinating America.

Rough rollout

While there’s no such thing as a good time for a pandemic, for CVS, the opportunity to prove its health care bona fides by inoculating millions of Americans against a deadly virus arrives at an opportune moment. In the early 2010s, the company looked around at its nearly 10,000 store locations—a massive brick-and-mortar footprint at a time when toothpaste, toilet paper, and even prescriptions were increasingly easy to get online—and concluded that it needed a new strategy. Its solution: pivot from store to one-stop health care provider. In 2014, the company took a big step in that direction by banning tobacco from its shelves, and went on to launch a network of “health hubs.” Chronic conditions account for 90% of the United States’ $3.8 trillion in annual health care spending. CVS aims to reimagine its long-standing MinuteClinics, where customers often address one-time health care needs, as places to manage those ongoing conditions.

A successful COVID-19 vaccine rollout could accelerate a transformation in the way shoppers see CVS, convincing them not just to, say, pick up their insulin prescription at CVS, but to see one of the company’s health care professionals about managing their diabetes. “Three years ago, it might have been hard to imagine that you would go to your doctor at a CVS,” says Lance Wilkes, an equity analyst for Bernstein Research. “If you’re trying to change public perception, and the public felt comfortable going into that setting, COVID vaccination would be a significant step.”

Already, the critical role CVS will play in vaccinating the public is clear. The company says that when it has the supply and the go-ahead, it will be able to provide 20 million to 25 million inoculations a month—almost 30% of the estimated 90 million vaccinations a month expected to be distributed through the entire retail pharmacy industry. On Feb. 11, CVS waded into the very first stages of these kinds of vaccinations, and it’s now offering immunizations to eligible populations at about 1,200 locations in 29 states.

But, as is so often the case where this virus is concerned, little has gone according to plan in the rollout so far. CVS’s first true test in the vaccination war was as a partner in the former Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed. Alongside competitor Walgreens, it was tasked in October with vaccinating staff and residents of long-term-care facilities—one of the populations most vulnerable to serious illness and death from coronavirus infection. CVS signed on to handle 60% of the 70,000 facilities enrolled in the program nationwide and scrambled to staff up. The company hired 10,000 technicians to join its staff of 50,000 immunizers (part of the company’s total workforce of almost 300,000) and began administering vaccines in December.

Despite all the preparation, hardly anybody was completely happy with the resulting rollout. State and local officials, nursing homes, and experts on public health, vaccines, and health care operations—Fortune spoke with 15 sources across those categories—were flummoxed by the corporate and governmental bureaucracy surrounding the nursing home rollout. Neither the government nor CVS released a timeline for the project or a deadline for completing it (at press time, the effort was still ongoing). But even without such a benchmark, critics are unanimous: The rollout has gone far too slowly. Tinglong Dai, an associate professor of operations management with a specialty in health at Johns Hopkins’ Carey Business School, says that, given the complexity of the task, assigning such a large share to a single company was a mistake: “With broader participation of local and independent pharmacies, we could have prevented many deaths and infections.”

To be fair, the critique is not specific to CVS; Walgreens experienced many of the same problems; indeed, experts say the lack of data on the rollout makes it difficult to glean whether one company did a better job than its competitor. One nursing home Fortune spoke to complained of scheduling a vaccine clinic with CVS only to later see it canceled, while Graham Briggs, a public health official for Olmsted County, Minn., says he lacked visibility into who in his community had been vaccinated since the federal program only reports vaccination data on a state level. The lack of available data left critics wondering whether the fault lay with the pharmacy chains’ execution of the program, or the government’s decision to enact this unprecedented partnership in the first place.

For its part, CVS points to the difficulties of what it was asked to do: implement a first-of-its-kind endeavor full of complications like the need to go room by room to vaccinate bed-bound patients and the uncertainty of treating dementia patients who don’t understand why they’re being asked to wear a mask or get a shot. The company has called the effort “a success,” citing an 84% decrease in nursing home COVID-19 deaths between late December and late February; second doses at assisted-living facilities are now 91% complete. (Walgreens says it has now completed a “majority” of its assigned vaccinations.) As of press time, with the effort nearing the finish line, CVS and Walgreens together had administered 7.4 million doses through the federal program.

As the architect of CVS’s COVID-19 strategy, Lynch arguably bears significant responsibility for the first wave of this effort—though she did not personally strike the deal with the federal government. As CEO, she’s undeniably charged with ensuring that it ends in a stronger and smoother manner than it began. And already, Lynch is looking ahead. What comes next—vaccinating the rest of the country—is a challenge on a far grander scale, but Lynch insists that is exactly what she and the company have been preparing for. Says the CEO: “Put us in the game.”

A ‘game of stamina’

In 2019, Lynch flew over the handlebars of her bicycle onto a cobblestone street while on a cycling trip in the Netherlands. It was a nasty spill that broke her hip and hand, and damaged her ribs. Lynch and her husband, Kevin, flew back to the U.S. for surgery that would pin her hip back together. For Lynch, the protracted hospital stay was, if nothing else, a perfect opportunity to become her own focus group. Is this what the experience of breaking a hip was like for other Aetna customers? How could she make the experience of breaking a hip better?

Lynch’s instinct to turn even her own health setback into an opportunity to troubleshoot her business is an indication of just how deep her drive to fix and improve goes. As an executive at first Cigna, then Magellan Health Services, then Aetna, she made her name taking on troubled businesses, like the dental and vision unit at Cigna, which she took from a 12% loss to an annual growth rate of 4% over three years in the late 2000s. She became so well known as an adept handler of crises that she was chosen to anticipate them, overseeing natural disaster preparation drills at Aetna. Before she finally moved to Aetna in 2012, the insurer had tried to hire her three times, says Meg McCarthy, Aetna’s former chief information officer. (Lynch says it was four.)

But for all the daredevil thrills of tackling disasters—natural and otherwise—there’s little doubt that a more humdrum set of skills was one of the things that drew the CVS board to Lynch. She ran two of the largest integrations in the industry: the $7.3 billion merger of Medicaid and Medicare insurer Coventry Health Care with Aetna in 2013 and 2014 and then the $70 billion mega-merger of Aetna with CVS.

Mergers, and particularly health care mergers, are complicated and unforgiving affairs. Before Coventry, Aetna’s last major integration had been the ’90s acquisition of U.S. Healthcare, which led to complaints and departures from customers and doctors. To avoid another such mess, Lynch dedicated herself entirely to the process; during the Coventry merger, she held an 8 a.m. meeting between players from both companies every workday for nearly two years. Along the way, especially as Aetna combined with CVS, she worked to learn aspects of the incoming businesses that she hadn’t yet encountered coming up in the insurance industry—including the retail side of CVS. That knowledge would prove vital for eventually landing the CEO job.

Lynch’s ability to marry merger minutiae with the big picture got attention. “She ensures execution of the operating details, and she has an excellent track record of driving growth and innovation,” says Larry Merlo, Lynch’s predecessor as CEO and a member of the board of directors as it chose his successor. Those who have followed Lynch’s career were not surprised to see those years of operations focus pay off. “For her, it’s been a game of stamina—and she has great endurance,” says Scott Walker, the CFO of Aetna, who first encountered Lynch 27 years ago, when he was an auditor at PwC and she was an executive working for his client Cigna.

After spending a day with Lynch, no one would question that endurance. The CEO wakes at 4:45 and is on her Peloton bike by 5:15. She’s usually taking calls by 7 a.m., working through the evening, when she’ll get back on a bike—a real one—to ride five or six miles with her husband, Kevin, at their homes in Cape Cod or Florida (before the pandemic, Lynch spent much of her time in Woonsocket, R.I., where CVS is headquartered). She works every single day, “without exception,” says Kevin, who’s been married to Lynch for five years and first met her when they were 18 and 19, waitress and cook in a summer romance at a 24/7 Cape Cod diner. (They reconnected in 2004, when he was negotiating a Cigna contract for the hospital system HCA and discovered that Lynch would be on the other side of the table. He gave her a call; she made him go to lunch with her assistant first to vet why he was reaching out.) Kevin tells the story of a former report of Lynch’s who, working on a project, told her husband he spent “three days with her yesterday afternoon.”

‘I felt like I was shedding armor’

But beyond her obvious work ethic and hard-charging schedule, those who worked with Lynch in the earlier stages of her career don’t seem to know much about her. (Kevin once mentioned his wife’s three siblings in passing to her assistant of seven years, who didn’t know her boss had any.) Even when Lynch was running Magellan Health Services, a behavioral health company, her staff didn’t know that she’d lost her mom, Irene, to suicide. “I was embarrassed,” says Lynch. “I thought people would judge me by it. They probably do.”

That changed in 2015, when Lynch became the president of Aetna. She says the title changed her perspective; she was finally high up enough to start to let her guard down. “I felt like I was shedding armor,” Lynch recalls. “I was my true, authentic self. I wasn’t hiding anything.”

While Lynch credits her experience navigating her Aunt Millie’s illness with setting her on her professional course, watching her mother suffer from mental illness throughout her early childhood is the experience that shapes much of how she does the job. For years, Lynch wasn’t ready to talk about her mother’s death—not just in public, but privately too. She worried about being judged, being seen as a girl without parents, who’s “not going to make anything of herself.” By 12, Lynch had already seen the failures of the American health care system up close: Her mom had struggled with mental illness for years before her death and wasn’t always able to access the kind of treatment she needed, Lynch remembers. Because Lynch was so young when her mother died, the experience didn’t rewrite her view of the American health care system in the same way sitting by her aunt’s hospital bed did. But once she started rising in the industry, it was always there as she thought about which parts of the health care system were in the most urgent need of transformation.

People who worked with Lynch before she started speaking out describe her as empathetic and willing to listen. But they also suggest that she seemed guarded, that she did not share much of herself. That description no longer applies. More than almost any other executive in corporate America, Lynch is now willing to talk about the hardest topics. She’ll share the realities of growing up with a parent suffering from mental illness. (“She was ill,” Lynch says of her mom. “I didn’t really know her.”) She’ll discuss the sacrifices the job takes, mentioning an earlier divorce and lost friendships. (“Friendships, relationships require spending time with people. When you’re working as much as I’ve worked in my career, I’ve probably lost some along the way.”) She’ll talk about her decision not to have children—because of both her single-minded dedication to her career and the trauma of losing her only parent as a child. (“The pain that I experienced—I didn’t want to have to help someone navigate that.”)

“It’s both hardened and toughened her—her personal level of expectation for herself,” says Jonathan Mayhew, who is the executive vice president for transformation at CVS and met Lynch two decades ago when they both worked for Cigna. “And yet for others, it’s created a compassionate sort of human, consumer orientation.”

For those reasons, Lynch has always paid a high level of attention to the way insurers—and now health care providers and pharmacies—treat mental health. She tells the story of a Magellan customer, a college student, who struggled with an eating disorder; Lynch became invested in Magellan’s deliberation in 2010 over whether to cover a stay in a treatment center and called the student to provide encouragement for her treatment journey (the CEO notes that the student has since recovered and is now a teacher). It’s hard to imagine that Lynch’s mother’s lack of consistent access to that kind of treatment wasn’t on her mind when she made that call.

Going local

By telling her story, Lynch has aimed to build trust with her workforce. As CVS becomes a bigger and bigger part of the vaccination fight, the company is going to need to create that same feeling among its customers.

“Pharmacists can be a major source of reassurance and trust,” says Col. John Grabenstein, a former Army pharmacist who, in 1996, wrote the American Pharmacists Association’s immunization training program, which still teaches pharmacists how to vaccinate today.

Before the mid-1990s, pharmacists in the U.S. didn’t vaccinate patients with any kind of regularity; it was usually a job for doctors or nurses. Washington State was the first, in 1994, to train its pharmacists in vaccine administration. Two years later, Grabenstein wrote his training manual, instructing pharmacists to insert the needle with the correct placement, correct angle, correct depth—not too high in the upper arm. Vaccination in pharmacies, especially against the flu, became more common throughout the 2000s. Today, 35 million Americans get their flu shots at a pharmacy.

Unlike an annual visit to a doctor’s office, many Americans step inside their local pharmacy several times a week, on weekends, on holidays. And many Americans—as CVS learned when about 60% of staff at long-term-care facilities at first declined to receive a coronavirus shot—are hesitant to get a new vaccine that was developed in record time. “Some people don’t respond to the first offer,” says Grabenstein. “A pharmacist can ask the same person a second time, a third time, a fourth time, until they finally say yes.”

The omnipresence of a local pharmacy in people’s lives is one factor that gives experts more confidence in CVS’s ability to vaccinate the U.S. general population than they had in its specialized long-term-care effort. Customers’ regular visits give pharmacies information that can help them reach high-priority patients. “The pharmacists know the people on chronic medication. They can make a roster of people with diabetes, people with heart disease, because they know the insulin users, the metformin users, the digoxin users,” says Grabenstein. With its digital infrastructure, CVS also has the capability for patients to schedule appointments online and to stay in touch—as any CVS customer who receives text reminders to pick up a prescription knows—to get them to return for a second dose.

But just as the coronavirus is not the flu, the coronavirus vaccine is not the flu vaccine. CVS pharmacies will have to set up space in the stores to observe patients for 15 minutes after they get the shot—a requirement unique to the COVID vaccine because of rare allergic reactions. If demand remains as high as it has been for months, CVS will have to ensure its online appointment-scheduling system remains functional and slots remain open. Pharmacists will need to schedule and plan so they don’t waste extra doses or allow the temperature-sensitive vaccines to go bad.

And for CVS, as much as vaccinating the general public presents an opportunity, it is also a risk. If for any reason the pharmacy’s vaccination rollout doesn’t go smoothly, that memory will stick with consumers for years to come.

The most-watched woman in corporate America

Normally, the CEO of CVS Health wouldn’t be spending much of her time on the pharmacy’s vaccination program. COVID, of course, is different. Lynch estimates that vaccine efforts are requiring “a fair amount” of her attention. While CVS Health chief medical officer Troyen Brennan is the executive officially tasked with executing the company’s vaccine rollout, Lynch has spent the past year working side by side with Brennan, applying her operational expertise to the pharmacy’s COVID strategy. Beyond the vaccination plans, that has entailed protecting the health and safety of CVS’s retail employees, setting up 4,800 COVID testing locations, troubleshooting issues like slow turnarounds for test results, and making sure medication and other essentials are always available to customers.

But like many of us, Lynch is also looking beyond the pandemic. She’s on what she calls the “march to 100”—that is, a $100 stock price, up from the $65 the stock averaged over the past year (the share price has slowly recovered from the hit it took after the 2018 Aetna acquisition, when Wall Street judged that the company overpaid for the insurer). Lynch has plans to digitize CVS’s health care delivery, providing services like digital appointments with medical professionals well beyond the pandemic. She aims to accelerate the use of alternative sites of care—that is, CVS stores instead of doctors’ offices—for patients. And along the way, she must solidify this new version of CVS in the minds of both consumers and investors. “When people think about health, I want them to think about CVS Health,” Lynch says.

Lynch will be doing all this as one of the most closely watched women in corporate America. The person in Lynch’s orbit who may have the best sense of what that will be like is Neela Montgomery, the former CEO of Crate & Barrel from 2017 to 2020, who is now leading CVS’s $91 billion retail pharmacy unit. “The highest-ranking female—someone’s got to be it at any given time,” Montgomery says. “Earlier in my own career, I used to think, I’m just stepping into the next big job, the same as anyone else. But you realize over time, that’s not true. Effectively, if you’re the first one, you’re always going to carry more weight and come under more scrutiny.”

But Lynch won’t be alone. Days before her start date in the role, CVS competitor Walgreens Boots Alliance announced a marquee hire of its own: Former Walmart and Starbucks executive Rosalind “Roz” Brewer will be chief executive for the $140 billion business, ranked No. 19 on the 500 list. (Brewer will be one of just two Black women currently leading Fortune 500 businesses.)

As Lynch says again and again, health care is personal. Before I began asking questions about Lynch’s experience losing two of her closest family members, I mentioned that I lost a parent at 26. Finishing our interview, running late to her next appointment—and she hates running late—Lynch stayed on the line to make an offer: “Losing a parent in your mid-twenties, I get it—if you ever want to talk about it.”

Changing the health care system from within was an ambitious goal for Lynch when she was a 28-year-old accountant, and remains an ambitious goal today. But if anyone can pull it off, it’s a leader who understands exactly what’s at stake.

“I don’t take it lightly that we have an opportunity to impact people’s lives every single day,” she says. “I’ve lived it, right?”