|

创业家埃里克·里斯靠着教授新创企业学习大型跨国企业做事方式声名鹊起,如今他又开始教大型企业向新创企业学习。 在耶鲁读本科时里斯就开始创业,后来又在不少公司工作过,让他忍不住好奇为什么有些企业会成功,而有些会失败。找寻原因的过程中,里斯发现了“精益化管理”的威力,这一概念首先因丰田等日本企业出名,核心论点在于企业的目标就是向客户输送价值,否则就是浪费资源。 在2011年出版的《精益创业》一书中,里斯将精益化管理的思路应用在创业上。他建议创始人少花点时间忙融资,搭建宏大的商业计划,多注意征求反馈收集数据,确保产品能满足真实需要,且能推动客户的需求。里斯还更进一步,提出大型官僚化企业应该采取类似措施,方能保持进步维持增长。 《精益创业》已成为商学院重要教材,也成了畅销书——目前销量超过100万本,里斯也为大大小小数十家企业提供咨询。本月出版的新书《创业之术》(Currency/企鹅兰登书屋,售价30美元)中,里斯归纳咨询经验,介绍了《财富》500强企业应该如何借鉴“创业式管理”的企业文化。在以下节选文本中,里斯讲述了劝服具有125年历史,30万员工的巨头通用电气转换思路的故事。——马特·海默尔 |

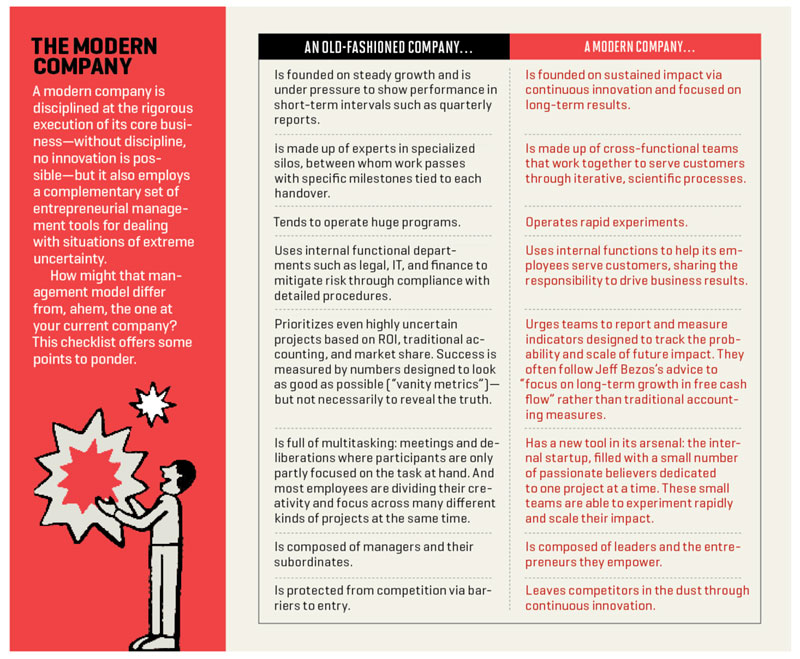

Entrepreneur Eric Ries rose to prominence by teaching ¬startups how to adopt the best practices of big, global ¬companies. Today he’s also teaching huge companies how to behave more like the upstarts. He began his entrepreneurial career while still a Yale undergrad, and his mixed track record at multiple companies stoked his curiosity about what ideas separated the winners from the losers. His exploration of that topic led Ries to embrace “lean management”—the concept, made famous by Toyota and other Japanese manufacturers, that any business process that isn’t focused on delivering value to the customer is, ultimately, a waste of resources. In his 2011 book, The Lean Startup, Ries applied lean-management thinking to entrepreneurship. He urged founders to spend less time chasing funding and building epic-scale business plans, and more time soliciting feedback and harvesting data to make sure the product they were building met a real need that would drive customer demand. Ries also went a step further—arguing that big, bureaucratic companies needed to adopt similar approaches to evolve and sustain their own growth. The Lean Startup became a business-school staple and a blockbuster—it has sold more than a million copies—and Ries has gone on to advise dozens of companies of all sizes. In a new book out this month, The Startup Way (Currency/Penguin Random House, $30), Ries draws on his experience to describe how Fortune 500 companies can adopt a culture of “entrepreneurial management.” In this edited excerpt, he recounts how he persuaded managers at General Electric (GE, -0.77%) , a 125-year-old, 300,000-employee behemoth, to embrace a different kind of thinking. —Matt Heimer |

图片:Manfred Koh

|

夏日一个午后,一家大型美国企业的工程师和高管坐在庞大培训中心的管理人员培训教室里,讨论着几亿美元的大生意。他们下一个五年计划是开发新款柴油和天然气发动机,目标是打入新市场,气氛十分热烈。新款发动机命名为X系列,从能源生产到机车动力很多行业都可以广泛应用。 对在座人士来说整个计划很明确,只有一位参会者例外,他之前根本不了解发动机和能源,也不懂工业产品生产,所以只能问些儿童绘本作家苏斯博士可能问的初级问题: “做什么用的来着?船上?飞机上?海上还是陆地?还是火车上?” 在场的高管和工程师都忍不住嘀咕,“这家伙是谁啊?” 这个人就是我,而这家企业是通用电气,美国历史最悠久也最可敬的企业之一。我不是公司高管,背景不是能源不是医疗,跟通用电气庞大的业务一点也不沾边。我只是个创业者。 但那天,时任通用电气总裁兼首席执行官的杰弗里·伊梅尔特和时任副总裁的贝斯·康斯托克邀请我去纽约科罗顿维尔,也即通用电气培训中心所在地,原因是他们对我在第一本书中提出的观点很感兴趣。我认为新创企业管理方式可适用于任何行业,不论企业规模大小,也不论身处何种经济部门。他们认为通用电气也要开始按照这些原则改变,最终目标是推动企业增长,提高适应能力,以及打造确保企业长期繁荣的制度传承。 我从没想过会参加那次会议,也没预料到。刚工作时我是软件工程师,后来开始创业。如果你印象中科技创业者就像个小孩,喜欢躲在父母家中地下室里钻研,没错,我就是这样的。我第一次尝试创业是在互联网泡沫时期,一败涂地。我第一次出版大作是1996年,书名是《Java游戏编程的黑色艺术》,上次去亚马逊网站看还有卖,99美元一本,从这些项目都看不出来之后我主要工作会变成宣传新型管理方式。 我搬去硅谷后,发现很多企业成功和失败的规律。我开始总结模式,研究如何激发创业精神。之后我开始写,2008年开始在网上写,后来集结成书,2011年出版了《精益创业》。 书中提出了当时看来比较激进的观点。我认为新创企业应该理解为“在极端不确定情况下努力创造新产品和服务的人类组织。”这个概念有意提得比较泛,没有明确企业的规模,具体形式(公司、非盈利组织还是别的什么),也没指明行业和领域。在这个广泛的定义下,任何人,不管官方职位如何都可以有创业精神。我认为创业家可以在任何地方——小企业、大巨头、医疗系统、学校,甚至政府机关。只要人们勇于畅想并践行新观念,采用新工作方式,或将产品或服务拓展至新市场服务新客户,都可称为创业。 该论点也解释了为何过去五年里我一直过着双面生活。上午我经常跟大企业、领先市场的公司打交道,下午则主要见新创企业,从发展极为迅速的硅谷神话级公司到刚起步种子阶段的小公司都有。他们问我的问题却出奇一致: 如何鼓励下属像创业者一样思考?如何保住现有客户的同时为新市场打造新产品?如何营造擅长平衡现有业务与新增长点的经营文化? 通过向合作公司学习,我开始构思新作,主要关于不限于“起步阶段”的管理规则,尤其适应于成熟企业甚至大型企业的。内容关键在于传统管理与创业式管理如何完美结合。 内容主要是案例分析和通过各种渠道收集的经验:有通用电气和丰田之类知名跨国企业;有著名科技先锋亚马逊、Intuit和Facebook;有新一代发展迅速的新创企业,例如Twilio、Dropbox和爱彼迎;当然也有无数没听过的新新创企业。 通过互相合作,我发现在21世纪创业精神确实可能重振管理思路。这可不限于某个特定行业里的工作方式,而是各地人们工作或希望工作的方式。我称之为创业之术。 通用电气管理者选择X系列发动机项目试水并非偶然。他们认为如果我能成功革新这个规模巨大又跨平台合作的发动机项目,那么精益创业思路就能在全企业推行,从而实现多项业务中简化工作流程的目标。 我在科罗顿维尔开完第一个会没几个小时,又去培训中心另一个很像商学院的教室里,身边都是X系列发动机开发各相关部门的工程师,各部门首席执行官,还有几位负责跨部门业务级别很高的管理者,我这次拜访正是他们邀请。 我们只想回答杰夫·伊梅尔特一直追问的问题:“为什么X系列发动机开发需要五年?” 我首先开腔,请X系列研发团队梳理一下五年计划。我的角色就是问问题,弄清哪些是团队明确的,哪些只是猜测。产品究竟是否可行?客户是谁,怎么知道他们真正需要?时间线里哪些由物理法则决定,哪些受制于通用电气内部流程? 紧接着该团队介绍就X系列发动机已经批准的业务,其中有个收入预测图,图表中的曲线随着时间一路向上,速度非常之快,仿佛这款还没造出的发动机未来30年里每年真能赚数十亿美元。贝斯·康斯托克回忆说:“感觉所有商业计划里增长曲线都特别漂亮,好像五年就能涨到月亮上去,万事俱备非常完美。” |

On a summer afternoon, a group of engineers and executives at one of America’s largest companies met in a classroom deep in the heart of their sprawling executive training facility to discuss their multi–$100 million, five-year plan for developing a new diesel and natural-gas engine. Their goal was to enter a new market space; excitement was running high. The engine, named Series X, had broad applications in many industries, from energy generation to locomotive power. All of this was very clear to those assembled in the room. Except to one person, who had no prior knowledge of engines, energy, or industrial product production and was therefore reduced to asking a series of questions Dr. Seuss might have posed: “What is this used for again? It’s in a boat? On a plane? By sea and by land? On a train?” The executives and engineers alike were no doubt wondering, “Who is this guy?” That guy was me. The company was GE, one of America’s oldest, most venerable organizations. I’m not a corporate executive. My background is not in energy or health care or any of GE’s myriad industrial businesses. I am an entrepreneur. But GE’s then–chairman and CEO Jeffrey Immelt and then–vice chair Beth Comstock had invited me to Crotonville, N.Y., that day because they were intrigued by an idea proposed in my first book: that the principles of entrepreneurial management could be applied to any industry, size of company, or sector of the economy. And they believed their company needed to start working according to those principles. The goal was to set GE on a path for growth and adaptability, to build a legacy that would allow the company to flourish long term. My journey to that meeting was an unlikely—not to mention unexpected—one. Early in my career I trained as a software engineer, after which I became an entrepreneur. If you’ve ever pictured a stereotypical tech entrepreneur as a kid, laboring away in their parents’ basement—well, that was me. My first foray into entrepreneurship, during the dotcom bubble, was an abject failure. My first published writing, 1996’s scintillating The Black Art of Java Game Programming, is, last time I checked, available used on Amazon.com for 99¢. None of these projects seemed like harbingers of future years that would be spent advocating for a new system of management. After I moved to Silicon Valley, though, I started to see patterns in what was driving both successes and failures. And, along the way, I started to formulate a model for how to make the practice of entrepreneurship more rigorous. Then I began writing about it, first online beginning in 2008, and then in a book, The Lean Startup, published in 2011. In the book, I made a claim that seemed radical at the time. I argued that a startup should be properly understood as “a human institution designed to create a new product or service under conditions of extreme uncertainty.” This definition was purposefully general. It didn’t specify anything about the size of the organization, the form it took (company, nonprofit, or other), or the industry or sector of which it was a part. According to this broad definition, anyone—no matter the official job title—can be cast unexpectedly into the waters of entrepreneurship. I argued that entrepreneurs are everywhere—in small businesses, mammoth corporations, health care systems, and schools, even inside government agencies. They are anywhere that people are doing the honorable and often unheralded labor of testing a novel idea, creating a better way to work, or serving new customers by extending a product or service into new markets. That idea helps explain why, for the past five years, I’ve been living a double life. I’ve had plenty of days when I met with the leader of a mammoth, market-leading organization in the morning and then, in the afternoon, spent time with startups—from massive hypergrowth Silicon Valley success stories to tiny seed-stage hopefuls. The questions I’m asked are amazingly consistent: How do I encourage the people who work for me to think more like entrepreneurs? How can I build new products for new markets without losing my existing customers? How can I create a culture that will balance the needs of existing business with new sources of growth? Learning from the companies I have been working with, I began to evolve a new body of work about principles that apply beyond the “getting started” phase, particularly in established and even large-scale enterprises. It’s about how traditional management and entrepreneurial management can work together. It is informed by case studies and wisdom from a variety of sources: iconic multinationals like GE and Toyota; established tech pioneers like Amazon, Intuit, and Facebook; the next generation of hypergrowth startups like Twilio, Dropbox, and Airbnb; and countless emerging startups you haven’t heard of—yet. Working with them, I have seen that entrepreneurship has the potential to revitalize management thinking in the 21st century. This is no longer just the way people work in one industry. It’s the way people everywhere work—or want to work. I call it the Startup Way. It was no accident that GE’s leaders had picked Series X as the first project to test. The thinking was that if we could get this huge, multiplatform engine project operating in a new way, there would be no limit to Lean Startup applications companywide, which aligned perfectly with the company’s desire to simplify its way of working across its many businesses. Hours after my first meeting in Crotonville, I found myself in a business school–type classroom elsewhere in the building, along with engineers representing the businesses involved in the Series X engine development, the CEOs of each of those businesses, plus a small cross-functional group of top-level executives who had orchestrated my visit. We had gathered to try to answer one of Jeff Immelt’s most persistent questions: “Why is it taking me five years to get a Series X engine?” I kicked off the workshop by asking the Series X team to walk us through their five-year business plan. My role was to ask questions about what the team actually knew vs. what they had guessed. What do we know about how this product will work? Who are the customers, and how do we know they will want it? What aspects of the timeline are determined by the laws of physics, vs. GE’s internal processes? The team proceeded to present the currently approved business case for the Series X, including a revenue forecast with graph bars going up and to the right with such velocity that the chart showed this as-yet-unbuilt engine making literally billions of dollars a year as far into the future as 30 years hence. Beth Comstock recalls: “It was like all the business plans we see, with a hockey stick that is going to grow to the moon in five years, and everything is going to be perfect.” |

|

但只要深挖一点,当然就会发现没那么简单。但最大的问题还是:为什么开发这款发动机要那么久? 我不想刻意降低其中面临的技术挑战:新产品需要巨大的工程量,还要遵从复杂的设计参数,要符合新的量产工厂和全球供应链需要。很多聪明人做了大量工作,才能确保计划可行,技术准备充分。 但技术上面临困难主要还是规范。这款产品得支持多种环境下的各种用途(想象下在海上、固定钻井、火车、发动机和移动水压开采时,对发动机要求必然不一样)。各种用途基于对一系列市场、竞品以及财务收益的假设,还要同时支持很多客户。 各种“需求”都是采用传统市场调研技术收集。但调研和焦点团体法并非实验室里做实验。客户对自己要什么并不是总清楚,虽然经常很愿意提要求。虽然要为同一产品多类客户服务,也并不意味着非这么做不可,也许可以想办法缩短生产周期。 关于计划里的商业假设也有很多问题。在座高管之一,时任通用电气全球创新和新型号执行董事的史蒂夫·里果利回忆称,“我们对市场和客户有一系列深信不疑的假设。客户希望获得多少百分点的收益?是直接卖还是出租?经销渠道要不要花钱?这种问题有几十个,我们问这个团队时发现24个问题只能答上两个。”里果利称这时才有点“眉目”。大家一直盯着技术风险,即产品能不能造出来,却忽略了推广和销售风险,即这款产品到底该不该研发? 测试市场最好的方式就是直接把产品拿去问客户,当天我就提出了非常激进的建议:先造出MVP柴油发动机。所谓MVP是指“最简化可行产品”,也是在《精益创业》中谈过的。MVP产品里只有刚好能满足早期用户的功能,可以迅速造出,小规模可控地投放,随后收集反馈供下一步产品开发借鉴。 X系列发动机团队总想着造出能在多种环境下工作的设备。结果是项目涉及层面多,受到预算和政治环境各种限制。如果先针对某种具体场景造一款简单产品出来,将复杂问题简单化呢? 房间里立刻议论纷纷。工程师表示做不到。有个人还说了个笑话:“也不是完全没可能,我可以去竞争对手那买一款发动机,涂上商标再把我们的贴上去。”响起一阵尴尬的笑声。 当然了,他们不会真去做,不过开玩笑之后他们谈起五大用途中哪个最容易实现。海上使用得防水,移动水压开采得有轮子,最后团队认为固定发电机用的技术上最简单。一位工程师认为研发周期可从五年减至两年。 “从五年减到两年,进步很大,”我说。“不过别满足,我们继续。新时间线上,造出第一台发动机要多久?”此问题再次引起一些不满之声。有些参与者开始不厌其烦地向我解释大规模量产的经济性。不管后续造多少产品,建工厂和供应链花的时间差不多。 我再次表示抱歉:“请原谅我的无知,但我问的不是一条发动机生产线,而是造出一台发动机需要多久?应该有测试机生产流程的是吧?”确实有,第一台原型机要在一年内完成制造和测试。我问大家会不会有客户对原型机感兴趣,一位副总裁突然说,“有个客户每个月都来我办公室想买。我很确定他们会愿意买。” 房间里的气氛顿时有点转向。现在新产品交到客户手上从五年减到一年了。不过团队讨论还在继续。“如果向特定客户出售一台发动机的话,”一位工程师说,“我们都不用造全新的出来,可以把现有的产品改一改。”所有人都一脸惊愕盯着他。原来通用电气一款叫616的产品只要稍微改动,就能符合发电设备的需要。 新款MVP比起原计划,速度简直快太多:从五年多变成不到六个月。只花了几小时,也就问了几个简单的问题,我们就将项目时间大为缩短,还推动团队迅速学习。如果他们愿意继续这种思路,可能会为企业节省数亿美元。如接下来问题还有很多。万一启动客户不想买MVP了呢?万一因为服务和支持网络不够力度,订单非常少呢?现在发现问题难道不比五年后发现好么? 老实说:我非常兴奋。看起来结果非常好。 事实真的如此么?研讨会结束时,一位坐在后面的高管再也忍不住了。他问道,“向一位客户卖一台发动机到底有什么意义?”在他看来,我们从讨论可能价值数十亿的项目转为讨论毫无意义的小生意。他继续说:即便撇开卖一台发动机这种无稽之谈,但只针对一位客户的需求会将产品的目标市场减少80%。对这笔投资的回报率影响怎么算? 接下来发生的事我会永远记得。“你说得对,”我说。“如果我们不需要学习,如果你仍然坚信之前的计划,参与者的预测也跟几分钟前毫无变化,那么我说的就全都是废话。测试就是暂时摆脱实际执行计划,重新看待问题。”不骗你,那位高管立刻一脸信服。 本来我在通用电气的工作可以就此结束,不过好几位高管坚持让我留下。大家开始讨论起制造MVP可能出岔子的地方:如果客户的需求不一样怎么办?如果设备需要的服务和支持比预想中复杂怎么办?如果客户使用的环境更艰苦怎么办?如果新市场中客户不信任我们的品牌怎么办? 当谈话从“这个外人怎么想?”转为“我们自己怎么想?”情况就完全不一样了。 马克·里特尔时任通用电气全球研究部门高级副总裁兼首席技术官,也是在场所有工程师最尊敬的人,他之前明确表示怀疑,让工程师们很担心。研讨会结束时,他的话也让所有人惊讶:“我明白了,问题在我。”他深切理解了企业行动要更迅速,意味着他跟其他领导者也要跟着适应。产品制造的标准流程拖慢了企业增长,作为流程负责人,他也要做出改变。 里特尔回忆说,“最重要的就是研讨会改变了团队的态度,从害怕犯错变成积极投入,勤奋思考而且用于承担风险愿意尝试,管理团队不再担心出错,而是想着验证假设。思路真的放开了。” X系列发动机团队由此变成通用电气的先锋项目之一,后来统称为FastWorks。团队迅速将测试发动机投入市场,很快获得五台发动机订单。期间他们按照传统流程持续研发,一边等待着马克·里特尔说的“大爆发”,通过MVP他们收集了市场意见,也获得了收入。 还有很重要的一点要提一下。研讨会期间,还有之后几个月里,并没有人给工程师们发号施令。我没有,贝斯·康斯托克没有,马克·里特尔没有,甚至杰夫·伊梅尔特也没有。只要提供正确的思维框架,重新思考原先的假设,工程师们通过分析思考就提出了全新方案。很明显,当时在场所有人都认为这种方法可行,团队也获得了理想结果,换个方式都是做不到的。 之所以通用电气能在如此发展阶段实现自上而下改变,是因为正是锐意进取积极变革的人在努力推动。我讲的这个故事是亲眼所见。但这不只是通用电气的故事。其核心在于,勤奋努力的创始人可以在内部推广创业精神,促进企业发展。每家企业都有可资借鉴的工具,真正利用起来需要的只是勇气。 (财富中文网) 本文改编自《创业之术:现代企业如何利用创业式管理促进企业文化转型并推动长期发展》。版权归埃里克·里斯所有,出版社Currency和企鹅兰登书屋。 本文另一版本将刊登于2017年11月1日《财富》杂志,标题为《让巨头像新创企业一样思考》。 译者:冯丰 审稿:夏林 |

Things got more complicated, of course, as we dug deeper. But the biggest question looming over the room remained: Why does it take so long to build this engine? I don’t want to undersell the technical challenges involved: The specifications required an audacious engineering effort that combined a difficult set of design parameters with the need for a new mass-production facility and global supply chain. A lot of brilliant people had done real, hard work to ensure that the plan was feasible and technically viable. But a large part of the technical difficulty was driven by the specifications themselves. Remember that this product had to support multiple distinct uses in very different physical terrains (visualize how different the circumstances are at sea, in stationary drilling, on a train, for power generation, and in mobile fracking). The uses were based on a series of assumptions about the size of the market, competitors’ offerings, and the financial gains to be had by supporting many different customers at once. These “requirements” had been gathered using traditional market-research techniques. But surveys and focus groups are not experiments. Customers don’t always know what they want, though they are often more than happy to tell you anyway. And just because we can serve multiple customer segments with the same product doesn’t mean we have to. If we could find a way to make the technical requirements easier, maybe we could find a way to shorten the cycle time. There were also many questions about the plan’s commercial assumptions. One of the executives present, Steve Liguori, then GE’s executive director of global innovation and new models, recalls, “We had a whole list of these leap-of-faith assumptions around the marketplace and the customer. What percentage gains is the customer looking for? Are you going to sell it or lease it or rent it? Are you going to pay for distribution? We had about two dozen of these questions, and it turns out that when we asked the team how many they thought they could answer, it was only two of the 24.” Liguori recalls this as the “aha moment.” The company had been so focused on the technical risks—Can this product be built?—that it hadn’t focused on the marketing and sales-related risks—Should this product be built? Since the best way to test market assumptions is to get something out to customers, I made what was, to the room, a really radical suggestion: an MVP diesel engine. The MVP, or “minimum viable product,” is a concept I explored in The Lean Startup. An MVP is a product with just enough features to satisfy early customers; producing one quickly, and making it available in a small, controlled way, can generate feedback that guides the next steps in a product’s development. The Series X team was trying to design a piece of equipment that would work in multiple contexts. As a result, it was caught up in the budgeting and political constraints that accompany such a multifaceted project. What would happen if we decided to target only one use case at first and make the engineering problem easier? The room went a little wild. The engineers said it couldn’t be done. Then one of them made a joke: “It’s not literally impossible, though. I mean, I could do it by going to our competitor, buying one of their engines, painting over the logo, and putting ours on.” Cue the nervous chuckles. Of course, they never would have actually done this, but the joke led to a conversation about which of the five uses was the easiest to build. The marine application had to be waterproof. The mobile fracking application needed wheels. Ultimately, the team arrived at a stationary power generator as the simplest technical prospect. One of the engineers thought this could cut their cycle time from five years to two. “Five years to two is a pretty good improvement,” I said. “But let’s keep going. In this new timeline, how long would it take to build that first engine?” This question seemed to once again cause some irritation in the room. The participants started to painstakingly explain to me the economics of mass production. It’s the same amount of work to set up a factory and supply chain, no matter how many engines you subsequently produce. I apologized once again: “Forgive my ignorance, but I’m not asking about one line of engines. How long would it take you to produce just one single unit? You must have a testing process, right?” They did, and it required that the first working prototype be done and tested within the first year. When I asked if anyone in the room had a customer who might be interested in buying the first prototype, one of the VPs present suddenly said, “I’ve got someone who comes into my office every month asking for that. I’m pretty sure they’d buy it.” Now the energy in the room was starting to shift. We’d gone from five years to one year for putting a real product into the hands of a real customer. But the team kept going. “You know, if you just want to sell one engine, to that one specific customer,” said one engineer, “we don’t even need to build anything new. We could modify one of our existing products.” Everyone in the room stared in disbelief. It turned out that there was an engine called the 616 that, with a few adjustments, would meet the specs for just the power generation use. This new MVP was literally an order of magnitude faster than the original plan: from more than five years to fewer than six months. In the course of just a few hours—by asking a few deceptively simple questions—we had dramatically cut the project’s cycle time and found a way for this team to learn quickly. And, if they decided to pursue this course, we could potentially be on track to save the company millions of dollars. What if it turned out that that first customer didn’t want to buy the MVP? What if the lack of a service and support network was a deal killer? Wouldn’t you want to know that now rather than five years from now? I’ll be honest: I was getting pretty excited. It seemed like a perfect ending. Or was it? As the workshop wound to its conclusion, one of the executives in the back of the room couldn’t stand it anymore. “What is the point,” he asked, “of selling just one engine to one customer?” From his point of view, we had just gone from talking about a project potentially worth billions to one worth practically nothing. His objections continued: Even putting aside the futility of selling only one engine, targeting only one customer use effectively lowered the target market for this product by 80%. What would that do to the ROI profile of this investment? I’ll never forget what happened next. “You’re right,” I said. “If we don’t need to learn anything, if you believe in this plan and its attendant forecast that we looked at a few minutes ago, then what I’m describing is a waste of time. Testing is a distraction from the real work of executing to plan.” I kid you not—this executive looked satisfied. And that would have been the end of my time at GE, except for the fact that several of his peers objected. The executives themselves started to brainstorm all the things that could go wrong that might be revealed by this MVP: What if the customer’s requirements are different? What if the service and support needs are more difficult than we anticipate? What if the customer’s physical environment is more demanding? What if the customer doesn’t trust our brand in this new market segment? When the conversation shifted from “What does this outsider think?” to “What do we, ourselves, think?” it was a whole new ball game. Mark Little, who was then senior vice president and chief technology officer of GE Global Research, was the person the engineers in the room most looked up to, and whose skepticism—voiced quite clearly earlier in the day—had them most worried. He ended our workshop by saying something that stunned the room: “I get it now. I am the problem.” He truly understood that for the company to move faster, he, along with every other leader, had to adapt. The standard processes were holding back growth, and he, as a guardian of process, had to make a change. “What was really important,” Little recalls, “was that the workshop changed the attitude of the team from one of being really scared about making a mistake to being engaged and thoughtful and willing to take a risk and try stuff, and it got the management team to think more about testing assumptions than creating failures. That was very liberating.” The Series X team turned into one of the many pilot projects for the GE program we came to call FastWorks. The team got the test engine to market dramatically sooner and immediately got an order for five engines. During the time they would have been doing stealth R&D in the conventional process, waiting for what Mark Little calls “the big bang,” they were gaining market insights and earning revenue from their MVP. I want to dwell on an important fact. During this workshop—and the months of coaching that followed—no one had to tell these engineers what to do. Not me, not Beth Comstock, not Mark Little, not even Jeff Immelt. Once presented with the right framework for rethinking their assumptions, the engineers came up with the new plan through their own analysis and their own insights. It became obvious to everyone in the room that this method had worked and that the team had arrived at an outcome that the company would not have been able to get to any other way. The reason GE was able to tackle changes at this level, at this stage, was because the transformation was driven very early on by people completely dedicated to making it happen. I’ve told you this story because it’s one I saw firsthand. But it’s not only a story about GE. It’s about how dedicated founders are the engine that powers entrepreneurship within an organization. Every company has levers that make it run. All it takes to pull them is courage. Adapted from The Startup Way: How Modern Companies Use Entrepreneurial Management to Transform Culture and Drive Long-Term Growth. Copyright © 2017 by Eric Ries. Published by Currency, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. A version of this article appears in the Nov. 1, 2017 issue of Fortune with the headline “Teaching a Tech Giant to Think Like a Startup.” |