|

上世纪90年代,互联网曙光初露——如同你认识的每个人一样,你也有着满脑子的互联网天才创意。因缘际会,你甚至与硅谷最炙手可热的风险资本家之一说上了话。这是你的地盘,这里星火已燃,东风将起——你就要在互联网上卖书了。(风投却打起了呵欠。) 你告诉风投,你将用数年甚或数十年打造公司的科技基础设施和仓储能力,不懈地关注客户体验——你甚至将公司命名为“Relentless.com”(译注:Relentless的意思是坚持不懈),以顺应那席卷而来的客户中心化浪潮。当然,你也得搞搞降价促销来换取市场份额,还得抓好物流环节,但假以时日,你将达到现象级的规模,可以销售任何东西——没错,是“任何”东西——给所有人。你将建立“银河系最大的商店”。 风投开始动心。当他们找你要一些实打实的财务预测数据时,你眼睛都不眨一下:上市之前,你和投资人当然要大笔投入现金。接下来是连续17个季度的赤字,这时你会多费点口水四处交涉。头9年里你将带着30亿美元的负债运营——直到最终开始盈利,但在十年甚至更长时间里,平均利润薄到只有2%。 如果在电梯里推销这个项目,通常来说当电梯到达一层时故事也就结束了,但如果剧情不是这样,那后面一定有精彩好戏。亚马逊(Amazon)的创业故事现在已经成为公司铭刻在册的传奇,实际上杰夫·贝佐斯最初真的给自己的网站起名为“Relentless.com”,直到后来他改变了主意(你可以试试在浏览器输入这个网址)。当时的出资人就是来自Kleiner Perkins公司的传奇投资人约翰·杜尔, 1996年他给亚马逊投了最初的800万美元,三年后又投了另一个看似荒唐却雄心勃勃的初创企业,名叫谷歌(Google)。 杜尔在贝佐斯身上(同样也在拉里·佩奇和塞吉·布林身上)看到的不只是远大的商业眼光,还有把事情干到底的疯狂韧性。其他人也看到了这一点。摩根士丹利(Morgan Stanley)的分析师玛丽·米克尔在华尔街是出了名的亚马逊看涨派。1999年,她扫除了业界对亚马逊“激进”投资于基础设施的普遍担忧,称亚马逊的这一战略是“理性的冲动”。美盛集团(Legg Mason)的前任基金经理比尔·米勒连续15年跑赢标普500的记录无人能及,他在早期大笔投注亚马逊,911之后在亚马逊每股从三位数跌到6美元时更是双倍下注,最后股价回升。现如今亚马逊每股超过1600美元,相较于1997年亚马逊上市时除权调整后的收盘价,盈利106,669%。 若当事后诸葛,制造这种传奇很容易。任何人只要看看历史股价图,就能知晓上一代商界中谁将成为赢家或输家。而要想增长智慧,历史是最好的老师。亚马逊令人瞩目地崛起为今年《财富》美国500强中排名第八的企业,因此贝斯·考维特专门就亚马逊的话题在本期杂志上撰写了主题文章。文章揭示了一个核心的应该刻入史册的管理理念:创立伟大的公司,不仅需要持续不断地专注于把现在的事情做好(商业励志大师称之为“执行力”),还需要同样持续不断地专注于把将来的事做得更好。几年前贝佐斯告诉我的同事亚当·拉辛斯基,“亚马逊有三条宗旨:长线思维,客户至上,乐于创新。” 我们这个时代最负盛名的公司创始人——苹果(Apple)的史蒂夫·乔布斯,沃尔玛(Walmart)的山姆·沃尔顿,联邦快递(FedEx)的弗雷德·史密斯,西南航空(Southwest)的赫伯·凯勒尔,Intuit公司的斯考特·库克,Salesforce的马克·贝尼奥夫——本能地就知道这些。这一理念被一个又一个的商学院案例强化,被最受拥戴的投资人宣讲。沃伦·巴菲特的投资理念被投资界奉为圭臬,他常说,最好的持股期限是“永远”。 尽管拿什么指标来定义长期专注的公司并无清晰定论,从有限的资料来看,他们确实是更好的投资对象,至少好过那些短线思维的公司,也就是那些追求季度盈利目标、回购存货以提升股价、削减研发投入、砍掉对技术和员工的关键投资的那些公司。标普全球(S&P Global)去年10月的一份研究发现,对于大中型企业来说,与那些更关注“下一季度营收”的公司相比,“具有长远性”的公司在过去20年里持续带来更高的回报。(《财富》杂志与波士顿咨询公司(Boston Consulting Group)在去年11月共同公布了具有前瞻性的公司名单——财富50强企业——他们稳步再投资于产能以持续增长。) 麦肯锡全球研究所(McKinsey Global Institute)在2017年2月的一份研究中也同样揭示,有远见的公司财务表现也更好。自2001年至2014年,资料库里那些有长远打算的600家大中型公司,平均业绩增长比其他公司多47%,在收入增长和市场资本总额方面的表现也更好。麦肯锡的研究者发现,尽管在金融危机期间,这些公司的股价跌得也更多,但回调也更快。从更宏观的经济角度来看,有远见的公司在同一时期也创造了更多的就业。 既然如此,为何那么多公司还是习惯性地只关注下一季度?你猜对了,是因为华尔街。麦肯锡研究者发现,十个经理和主管中就有九个备受压力,要在两年甚至更短时间内提交可观的业绩。这些压力有许多是来自激进的对冲基金,这些基金大多茹毛饮血,追求短期内的投资回报。 |

It’s the 1990s, the dawn of the Internet age—and you, like everyone you know, has a genius of a dotcom idea. Somehow, you get in to see one of the hottest venture capitalists in Silicon Valley. Your pitch, fired up and ready: You’re going to sell books over the Internet. (The VC yawns.) You tell him that you’re planning to spend years, or really decades, building up technological infrastructure and warehouse capacity, focusing relentlessly on customer experience—you’ll even call the company “Relentless.com” to capture that ferocious customer-centricity. Sure, you’ll have to discount prices to gain market share, and take a hit on delivery, but in time you’ll have the phenomenal scale to sell “Anything … with a capital ‘A’ ”—to everyone. You’ll be “earth’s biggest store.” The VC stirs a bit. When he asks you for some hard-number projections, you don’t bat an eye: You and your investors will bleed cash, of course, before you go public. Then you’ll lose gobs more, going 17 straight quarters in the red. You’ll be in the hole about $3 billion in your first nine years as a going concern—and when you do eventually turn a profit, the margins will be razor thin for a decade or more, averaging about 2%. As elevator pitches go, this one would almost certainly end on the first floor. Except it didn’t. The story of Amazon.com—Jeff Bezos did indeed toy with the name “Relentless.com” before changing his mind (Go ahead: Type it in your browser)—is now engraved into the corporate mythos. The backer was the legendary John Doerr of Kleiner Perkins, who invested an initial $8 million in the company in 1996, and who three years later would back another ludicrously ambitious startup called Google. What Doerr saw in Bezos (and in Larry Page and Sergey Brin, for that matter) wasn’t just a grand business vision but also the maniacal tenacity to see it through. Others saw it too: In 1999, Morgan Stanley analyst Mary Meeker, a prominent Amazon bull on Wall Street, brushed off concerns of the company’s “aggressive” investment in its infrastructure, calling the strategy “rational recklessness.” Bill Miller, the former Legg Mason fund manager whose 15-year market-beating streak remains unmatched, invested early and heavily in Amazon—and then doubled down on the stock as it careened from triple digits to six bucks a share (after 9/11) and up again. It’s now trading above $1,600, a 106,669% gain over the split-adjusted closing-day price of its 1997 IPO. Such legend-making is easy in hindsight, of course. Everyone with access to a historical stock chart can plot the last generation’s certain winners and losers. That said, when it comes to gaining wisdom, the past is one of best teachers we have—and the striking rise of Amazon, No. 8 on the Fortune 500 and the subject of a profile by Beth Kowitt this issue,offers a core management lesson that ought to be carved in tablets by now: Building a great business requires not only a relentless focus on doing things well this minute (what business-book thumpers call “execution”), but also an equally relentless focus on doing things better in the future. As Bezos told my colleague Adam Lashinsky some years ago, “The three big ideas at Amazon are long-term thinking, customer obsession, and a willingness to invent.” Most of the celebrated company builders of our era—Apple’s Steve Jobs, Walmart’s Sam Walton, FedEx’s Fred Smith, Southwest’s Herb Kelleher, Intuit’s Scott Cook, Salesforce’s Marc Benioff—have known that instinctively. It’s a message reinforced by one biz-school case study after another and preached by the most acclaimed of investors. Warren Buffett, whose investing horizon is the horizon, likes to say his preferred holding period is “forever.” While the parameters of what defines a long-term-focused company are still somewhat squishy, the limited evidence so far suggests that they make better investments too. At least compared to short-termers: companies that are chasing quarterly earnings targets, buying back stock to pump their share prices, cutting R&D, and slashing other key investments in technology and people. An October study by S&P Global found that an index of large and midsize companies that, it says, “embody long-termism” had consistently higher returns on equity over the previous 20 years than various quartiles of companies with more of a “next quarter” focus. (Working with the Boston Consulting Group, Fortune also unveiled in November a list of forward-looking companies—the Future 50—that steadily reinvest in the capacity to grow.) A separate February 2017 study by the McKinsey Global Institute, likewise, found far better financial performance from far-horizon companies. From 2001 to 2014, long-term firms, drawn from a data set of more than 600 large and medium-size companies, had an average of 47% greater revenue growth than other firms as well as faster growth of earnings and market capitalizations. Although share prices for this group did suffer more during the financial crisis, they also recovered more quickly, the McKinsey researchers discovered. And from a broader economic standpoint, the farsighted companies also created a lot more jobs than other firms did during the same period. So why do so many companies still habitually manage to the next quarter? You guessed it: Wall Street. Nearly nine in 10 executives and directors feel mounting pressure to deliver strong financial results within two years or less, McKinsey found. And much of that push is coming from activist hedge funds, many of which are incentivized to goose their own investment returns in the near term. |

|

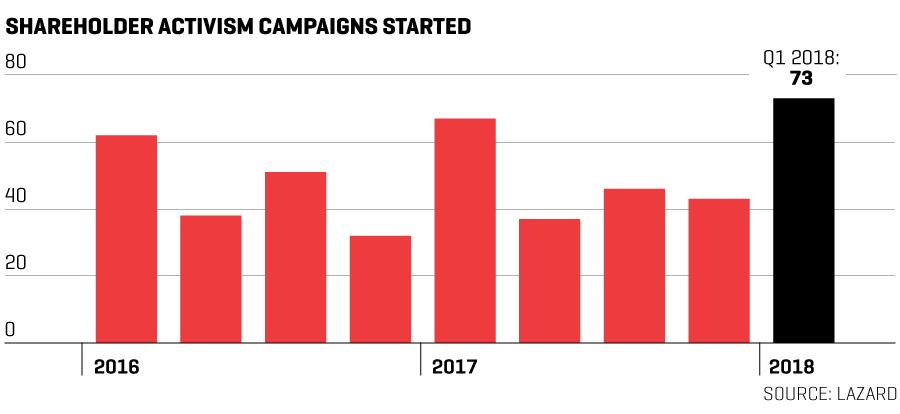

据追踪股东激进主义运动多年的拉扎德公司(Lazard)的消息,2018年的第一季度,发生了创纪录的73场股东激进主义运动,涉及250亿美元的资本。这些运动有些是要求分解或卖掉公司;有些要求股票回购或者董事会席位(激进者仅在第一季度就赢得了65个董事会席位)。据拉扎德公司透露,另一些只是对“恶意竞购”感兴趣,即为了阻止兼并收购项目进行,或者试图影响谈判。 麦肯锡咨询公司(McKinsey & Company)的全球管理伙伴鲍达民十多年来一直致力于鼓励企业放眼长远,不论在办公室还是董事会。他说:“不可否认有些激进者倒是更偏长远考虑些。”这些投资者经常能让一个长远战略得到更好的执行,也能让公司管理层在关键环节行动得更快。 但大多数激进者还是追求短期利益——而且他们的影响力常常超过其股份比例。“这其中的挑战,部分在于有些人能坐在多个董事会席位上,”鲍达民说,“有这么的股东激进运动在进行,很可能有些人有股东激进运动的经验并会分享给董事会。把其他董事会成员吓破胆,就是个不错的方法:‘天哪,你才不想那么做!就像你刚从战场回来,你根本不想再返回。’ ” 对于长效管理来说,更大的威胁是CEO薪酬,说这话的是《财富》杂志撰稿人布莱恩·杜梅,他与丹尼斯·凯利、迈克尔·尤西姆、以及罗德尼·泽梅尔合著了一部重要的新书《做多:为何远见是最好的短期策略》(Go Long: Why Long-Term Thinking Is Your Best Short-Term Strategy)。现今大多数CEO的报酬,部分体现在其任期内的股价。股东代言人——比如领航投资(Vanguard)的董事长比尔·麦克纳布——就在推动让CEO离职五年后才获得一半或更多的股票回报,而埃克森美孚(Exxon Mobil)实际上已经这么做了。 个中原理很简单:“如果你是石油公司的CEO,你可以决策削减勘探费用,这样一来支出减少,你的收入就突然很美妙了,”杜梅说,“但5年后,你的继任者就有麻烦了。” 这就是短期利益追逐者的问题所在。大部分的美国股东,即便不是几十年,也的确多年持有股票。但不可避免的是,如果经理人追求短期目标,这个国家的长期投资人就输了。(财富中文网) 此文首发于《财富》杂志2018年6月1日刊 译者:Hank |

A record 73 activist campaigns, deploying some $25 billion in capital, were initiated in the first quarter of 2018, according to Lazard, which has been tracking shareholder activism for years. Some campaigns push for a breakup or sale of the business; some for share buybacks or a seat on the board (activists won 65 board seats in the first quarter alone). Others are merely interested in “bumpitrage,” Lazard says—that is, to block an M&A deal from going through or to influence its negotiations. “To be sure there are some activists who actually behave a little more long term than we give them credit for,” says Dominic Barton, McKinsey & Company’s global managing partner, who has been championing efforts to encourage long-termism in corporate suites and boardrooms for more than a decade. These investors can often push for better execution of a far-thinking strategy and get company managements to move much faster in critical areas. But short-termers dominate this crowd—and their influence is often outsize compared with their shareholdings. “Part of the challenge is that people often sit on multiple boards,” says Barton. “Given the amount of activist activity going on, someone will very likely have had experience with a campaign and will share it with the board,” he says. “It’s a good way to scare the hell out of the other members: ‘My God, you don’t want to go through this! It’s like you’ve come back from a war. You just don’t want to go there.’ ” An even bigger threat to long-term managing is the way we do CEO compensation, says Fortune contributor Brian Dumaine, coauthor with Dennis Carey, Michael Useem, and Rodney Zemmel of an important new book titled, Go Long: Why Long-Term Thinking Is Your Best Short-Term Strategy. Today, most chief executives are rewarded based partly on how the stock performs during their tenure. Shareholder advocates like Vanguard chairman Bill McNabb are pushing instead to have half or more of the stock compensation vest five years after a CEO leaves the job—which is what Exxon Mobil actually does. The rationale is straightforward: “If you’re the CEO of an oil company, you can decide to cut way back on exploration and you’d have lower capital spending and suddenly your earnings are going to look great,” says Dumaine. “But five years down the road your successor is going to be in trouble.” That right there is the problem with short-termism. The great majority of shareholders in the U.S. do hold their stocks for years, if not decades. Inevitably, when managers chase the next quarter, it’s a nation of long-term investors who lose out. This article originally appeared in the June 1, 2018 issue of Fortune. |