新冠疫情在中国趋缓之际,西方国家和全球的疫情正处于失控爆发阶段。如今,医疗和科技水平全球第一的美国却在确诊人数和死亡人数上排名第一,其社交隔离措施带来的经济停滞和衰退,也需要一代人的时间去修复。如此巨大、不可承受的生命和社会代价,特朗普政府有着直接不可推脱的责任。

流行病学是一门建立在推测基础上的学科。研究人员将数据点放在一个地图上,推测它们之间的关联,继而神奇地发现可能的感染点和传播载体。这些推测,会形成假设理论的基础,这之后,艰苦的工作才正式开始:科学家煞费苦心地,全面地搜集证据,直到他们可以证实或否定这些理论。

在1854年,历史上最有名的流行病学专家约翰•斯诺就是这么做的。当时,他在伦敦地图上标出霍乱致死的病例,最终锁定了此次爆发的源头:一口受污染的井和水泵。现在,流行病专家也在做同样的事情,只是对象换成了新型冠状病毒和它引发的呼吸道疾病“新型冠状病毒病肺炎”。

这场全球性危机已进入第五个月了,根据约翰霍普金斯大学的数据,新冠病毒感染确诊病例激增至近200万人,遍布185个国家和地区,导致12.5万人死亡。然而,依然有众多的谜团有待解决:有多少人在不自知的情况下染上了病毒,而且还在继续传播?疫情到底要持续多久?什么时候才能安全地去上班?然而,没有人知道答案。

至于新冠病毒会如何重塑全球经济的一系列问题,例如,它会对全球经济造成多大的破坏?哪些行业损失最惨重,哪些会回弹,哪些会重塑?我们将用一整期的文章,以及大部分的每日网络报道来调查这些问题。基本上,我们整个编辑团队在过去几个月中,一直在未完成的地图上绘制数据点,尽力在这些点中寻找有意义的规律。这些当然都是推测,不过,你也可以把它看做是金融流行病学。

然而,在这个充满了“看似”,“可能”,和各种未知的领域中,还是有一些事情我们是掌握的,将这些教训分门别类地列出,可能有助于我们避免重蹈覆辙。

应对准备完全不足

“对于疫情的应对准备,我们过于满足了。”身为医生和纽约-长老会医院主席的史蒂芬•柯文说,“当然,无论是单个医院,还是一个国家,最终都能够挺过去。”过去几十年中,有好几次传染病威胁到美国,例如SARS、 中东呼吸症候群冠状病毒、H1N1禽流感,甚至是埃博拉,其中有几种在其他地区局地肆虐,比如SARS在亚洲的爆发,但是,没有哪一个像新冠病毒那样对美国造成如此之大的冲击。柯文说,在错误的安全感下,一些重要的问题被忽视了:“国家战略储备需要放什么?供应链有多脆弱?我们有多依赖快速物流?快速物流平时可以很快把防护用品送到医院,但出现疫情时,却变得效率很低。”

随着疫情的蔓延,这些问题得到了回答。4月初,纽约的疫情已经达到高峰,每周消耗70万个口罩,纽约州的口罩用量则达到了350万个,柯文说,按照这个速度,美国国家战略储备用不了多久就会耗尽。2月时,卫生与公共服务部部长亚历克斯•阿扎向一个参议院委员会表示,美国国家战略储备仅有3000万个N95口罩和1200万台呼吸机的储备量,此外,还有几百万个可能已过了保质期的口罩。

美国的医疗和制药供应链十分脆弱。口罩等个人防护装备大部分来自中国,此外,中国还是全球最大的活性药物成分、现代医药化学原料生产商和出口商,中国还生产了众多疾病诊断用化学试剂,例如分辨病毒株的聚合酶链反应测试。因此,如果出现了全球疫情,而供应链是从中国开始的,那么在到达美国之前可能就会中断。

测试诊断成瓶颈

当遇到可能具有大规模传染性的病毒,也就是病毒毒性高,又可以轻易地人传人时,任何诊断测试上的滞后都可能会导致灾难性的后果。新冠病毒便是这样一个案例,因为美国疾控中心最初开发的诊断测试存在缺陷,使得大规模测试很迟才开始,但更大的问题并不仅仅是政府所说的一个故障,而是一开始,所有的测试都必须经由联邦实验室进行,集中往往意味着瓶颈,一旦出现故障,则完全无法进行下去。

“即便一切进展顺利,哪怕疾控中心的测试也完全没有问题,美国的筛查测试能力也根本不足以应对这样的疫情局面。”负责此类诊断规范的美国食药局前专员斯科特•戈特列布说,“大学实验室和诊所实验室也都必须参与检测,但这需要时间,因此,你得从1月份就开始和他们合作,这样,到了2月和3月,才会准备好。”

“如果我们在2月中旬时,就有能力每周测试10万个样本,那么结果会大不一样。”戈特列布说。柯文对此也表示同意:“只有建立在早期测试和诊断基础上,我们才能对这类病毒防控进行情景规划。”

没有防控规划

现在的美国政府并没有一个防控规划。当我采访萨宾疫苗研究所全球免疫业务主席布鲁斯•杰林时,他像几乎所有美国人一样,正在居家隔离。隔离期间,他有了时间整理自己的车库,在一堆上世纪90年代的玩偶底下,他发现了之前的联邦政府制定的诸多防御病毒侵袭的规划。“疫情规划,我们是曾经是有的。”杰林讽刺说道,他也曾经是前卫生部助理副秘书长、国家疫苗项目负责人。2005年布什政府时代,他主导制定了美国首个流感防控和应急规划。

当时出现的“禽流感”也一度让社会紧张无比,决策者们做了很多推测,一旦真的变成大流行病,要对大量人口进行隔离的话,那经济与社会成本会是多少。“其中一个原则就是要列出,万一人们不能外出的话,有哪些后勤准备要做到位。”杰林回忆说,“例如,如果护士的学龄儿童呆在家,她怎么去上班?如果人们本来就是勉强度日的,一旦无法工作,怎么交得起房租?怎么按时缴纳抵押贷款?如果你强迫人们呆在家中,大量的问题就会接踵而至。”这些为减少社区传播的做法只是这个规划中的一部分。在新冠疫情期间,我们都意识到这类问题有多重要。

最后,这一切最发人深省的教训可能还在于,在这个前所未有的挑战面前,在疫情造成社会几近瘫痪的局面下,现任美国政府竟然完全无所作为。

2004年12月,小布什总统启用迈克•李维特任卫生与公共服务部的秘书长,李维特要求该机构的所有部门负责人向其汇报各自职责。

“他在决定应该保留谁,剔除谁。”前公共卫生应急响应部门助理秘书长、现任世卫组织助理总干事斯图尔特•西蒙森说,“我于是向他汇报应急响应方面的情况,会议结束时,我给了他两本书:约翰•巴里关于1918年西班牙流感的《大流感》和《911委员会报告》。”

“我当时说的大概意思是,我们认为我们将迎来另一场1918大流感。这是不可避免的,或早或晚都会发生。如果它发生时你还在任,而且没能意识到它的威胁,那么这本书的下一卷,你将成为主角。”(财富中文网)

译者:MS

责编:雨晨

新冠疫情在中国趋缓之际,西方国家和全球的疫情正处于失控爆发阶段。如今,医疗和科技水平全球第一的美国却在确诊人数和死亡人数上排名第一,其社交隔离措施带来的经济停滞和衰退,也需要一代人的时间去修复。如此巨大、不可承受的生命和社会代价,特朗普政府有着直接不可推脱的责任。

流行病学是一门建立在推测基础上的学科。研究人员将数据点放在一个地图上,推测它们之间的关联,继而神奇地发现可能的感染点和传播载体。这些推测,会形成假设理论的基础,这之后,艰苦的工作才正式开始:科学家煞费苦心地,全面地搜集证据,直到他们可以证实或否定这些理论。

在1854年,历史上最有名的流行病学专家约翰•斯诺就是这么做的。当时,他在伦敦地图上标出霍乱致死的病例,最终锁定了此次爆发的源头:一口受污染的井和水泵。现在,流行病专家也在做同样的事情,只是对象换成了新型冠状病毒和它引发的呼吸道疾病“新型冠状病毒病肺炎”。

这场全球性危机已进入第五个月了,根据约翰霍普金斯大学的数据,新冠病毒感染确诊病例激增至近200万人,遍布185个国家和地区,导致12.5万人死亡。然而,依然有众多的谜团有待解决:有多少人在不自知的情况下染上了病毒,而且还在继续传播?疫情到底要持续多久?什么时候才能安全地去上班?然而,没有人知道答案。

至于新冠病毒会如何重塑全球经济的一系列问题,例如,它会对全球经济造成多大的破坏?哪些行业损失最惨重,哪些会回弹,哪些会重塑?我们将用一整期的文章,以及大部分的每日网络报道来调查这些问题。基本上,我们整个编辑团队在过去几个月中,一直在未完成的地图上绘制数据点,尽力在这些点中寻找有意义的规律。这些当然都是推测,不过,你也可以把它看做是金融流行病学。

然而,在这个充满了“看似”,“可能”,和各种未知的领域中,还是有一些事情我们是掌握的,将这些教训分门别类地列出,可能有助于我们避免重蹈覆辙。

应对准备完全不足

“对于疫情的应对准备,我们过于满足了。”身为医生和纽约-长老会医院主席的史蒂芬•柯文说,“当然,无论是单个医院,还是一个国家,最终都能够挺过去。”过去几十年中,有好几次传染病威胁到美国,例如SARS、 中东呼吸症候群冠状病毒、H1N1禽流感,甚至是埃博拉,其中有几种在其他地区局地肆虐,比如SARS在亚洲的爆发,但是,没有哪一个像新冠病毒那样对美国造成如此之大的冲击。柯文说,在错误的安全感下,一些重要的问题被忽视了:“国家战略储备需要放什么?供应链有多脆弱?我们有多依赖快速物流?快速物流平时可以很快把防护用品送到医院,但出现疫情时,却变得效率很低。”

随着疫情的蔓延,这些问题得到了回答。4月初,纽约的疫情已经达到高峰,每周消耗70万个口罩,纽约州的口罩用量则达到了350万个,柯文说,按照这个速度,美国国家战略储备用不了多久就会耗尽。2月时,卫生与公共服务部部长亚历克斯•阿扎向一个参议院委员会表示,美国国家战略储备仅有3000万个N95口罩和1200万台呼吸机的储备量,此外,还有几百万个可能已过了保质期的口罩。

美国的医疗和制药供应链十分脆弱。口罩等个人防护装备大部分来自中国,此外,中国还是全球最大的活性药物成分、现代医药化学原料生产商和出口商,中国还生产了众多疾病诊断用化学试剂,例如分辨病毒株的聚合酶链反应测试。因此,如果出现了全球疫情,而供应链是从中国开始的,那么在到达美国之前可能就会中断。

测试诊断成瓶颈

当遇到可能具有大规模传染性的病毒,也就是病毒毒性高,又可以轻易地人传人时,任何诊断测试上的滞后都可能会导致灾难性的后果。新冠病毒便是这样一个案例,因为美国疾控中心最初开发的诊断测试存在缺陷,使得大规模测试很迟才开始,但更大的问题并不仅仅是政府所说的一个故障,而是一开始,所有的测试都必须经由联邦实验室进行,集中往往意味着瓶颈,一旦出现故障,则完全无法进行下去。

“即便一切进展顺利,哪怕疾控中心的测试也完全没有问题,美国的筛查测试能力也根本不足以应对这样的疫情局面。”负责此类诊断规范的美国食药局前专员斯科特•戈特列布说,“大学实验室和诊所实验室也都必须参与检测,但这需要时间,因此,你得从1月份就开始和他们合作,这样,到了2月和3月,才会准备好。”

“如果我们在2月中旬时,就有能力每周测试10万个样本,那么结果会大不一样。”戈特列布说。柯文对此也表示同意:“只有建立在早期测试和诊断基础上,我们才能对这类病毒防控进行情景规划。”

没有防控规划

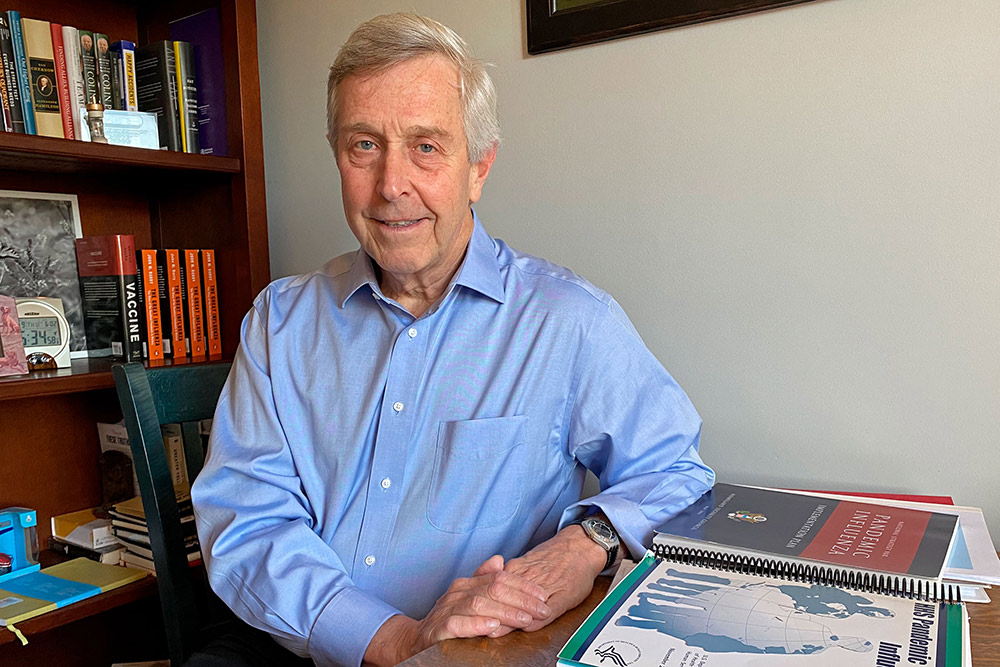

现在的美国政府并没有一个防控规划。当我采访萨宾疫苗研究所全球免疫业务主席布鲁斯•杰林时,他像几乎所有美国人一样,正在居家隔离。隔离期间,他有了时间整理自己的车库,在一堆上世纪90年代的玩偶底下,他发现了之前的联邦政府制定的诸多防御病毒侵袭的规划。“疫情规划,我们是曾经是有的。”杰林讽刺说道,他也曾经是前卫生部助理副秘书长、国家疫苗项目负责人。2005年布什政府时代,他主导制定了美国首个流感防控和应急规划。

当时出现的“禽流感”也一度让社会紧张无比,决策者们做了很多推测,一旦真的变成大流行病,要对大量人口进行隔离的话,那经济与社会成本会是多少。“其中一个原则就是要列出,万一人们不能外出的话,有哪些后勤准备要做到位。”杰林回忆说,“例如,如果护士的学龄儿童呆在家,她怎么去上班?如果人们本来就是勉强度日的,一旦无法工作,怎么交得起房租?怎么按时缴纳抵押贷款?如果你强迫人们呆在家中,大量的问题就会接踵而至。”这些为减少社区传播的做法只是这个规划中的一部分。在新冠疫情期间,我们都意识到这类问题有多重要。

最后,这一切最发人深省的教训可能还在于,在这个前所未有的挑战面前,在疫情造成社会几近瘫痪的局面下,现任美国政府竟然完全无所作为。

2004年12月,小布什总统启用迈克•李维特任卫生与公共服务部的秘书长,李维特要求该机构的所有部门负责人向其汇报各自职责。

“他在决定应该保留谁,剔除谁。”前公共卫生应急响应部门助理秘书长、现任世卫组织助理总干事斯图尔特•西蒙森说,“我于是向他汇报应急响应方面的情况,会议结束时,我给了他两本书:约翰•巴里关于1918年西班牙流感的《大流感》和《911委员会报告》。”

“我当时说的大概意思是,我们认为我们将迎来另一场1918大流感。这是不可避免的,或早或晚都会发生。如果它发生时你还在任,而且没能意识到它的威胁,那么这本书的下一卷,你将成为主角。”(财富中文网)

译者:MS

责编:雨晨

Epidemiology is a science of “seems to be” steps. Researchers plot data points on a map and speculate connections between them, conjuring up likely nodes of infection and possible vectors of transmission. Such guessing, if you will, forms the basis for hypotheses, and then the truly hard work begins: Scientists gather evidence—systematically, painstakingly—until they can prove or disprove those theories.

That’s what John Snow, history’s most famous epidemiologist, did in 1854, when he plotted deadly cases of cholera on a map of London, eventually tracing the outbreak to a single contaminated well and water pump. And that’s what’s happening now, with the novel coronavirus and respiratory disease it causes, COVID-19.

As we enter the fifth month of this worldwide crisis—a viral pandemic that has grown feverishly to nearly 2 million confirmed cases in 185 countries or regions, and more than 125,000 deaths, according to researchers at Johns Hopkins University—there are still plenty of mysteries to solve. How many people are unknowingly infected with (and possibly spreading) the virus? How long will the pandemic last? When is it safe to go back to work? Well, no one quite knows.

As to the question of how the coronavirus will reshape the global economy—How much damage will it do? Which industries will suffer the most, bounce back, be reinvented?—we have devoted this entire issue and most of our daily online coverage to investigating. Virtually our entire editorial team has spent the past few months plotting data points on unfinished maps and doing our best to draw meaningful patterns among them. It’s guesswork, to be sure—though you might think of it as financial epidemiology as well.

But in the sea of seems-to-bes, maybes, and outright unknowns, there are also things that we do know—and cataloging those lessons will perhaps keep us from repeating our mistakes again.

“Let’s start with the premise that we’ve been complacent about our preparation for such a pandemic,” says Steven Corwin, who is both a physician and the president and CEO of New York–Presbyterian hospital. “And I don’t think there’s any question—whether it’s an individual hospital, whether it’s as a country, we’ve been able to skate by.” For all the would-be plagues that have threatened American shores in the past couple of decades—SARS, MERS-CoV, H1N1 influenza, even Ebola—none delivered the knockout blow to the U.S. that COVID-19 has, even if a few were devastating elsewhere. Our false sense of security has led us to put off tackling important questions, Corwin says: “What do you need in the Strategic National Stockpile? How fragile is the supply chain? How much are we dependent upon just-in-time delivery—which, though it makes us more efficient in terms of health care, doesn’t necessarily provide resiliency?”

As it happens, the pandemic answered those questions for us. “We’re now at the peak of this in New York,” says Corwin, in early April. “We’re using 700,000 masks a week, and we’re 20% of the New York system—which works out to 3.5 million masks this week for the downstate New York area. At that rate, the Strategic National Stockpile doesn’t go a long way.” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar told a Senate committee in February that the Strategic National Stockpile had a mere 30 million surgical masks and 12 million respirators (the N95 masks that filter out most smaller viral particles) in reserve, plus a few million more that were likely past their expiration date.

We know that our medical and pharmaceutical supply chains are vulnerable. It’s not only masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE) that largely come from China. That nation, for example, is also the world’s largest producer and exporter of active pharmaceutical ingredients, the chemical feedstock of modern medicine. China also produces many of the chemical reagents that are used in disease diagnostics, such as polymerase chain reaction (or PCR) tests that identify viral strains. So, if in the midst of a pandemic, the supply starts there, the chain may break before it gets here.

On that front, we know that, when it comes to a potentially pandemic strain—a virus that is both virulent and easily transmissible from human to human—any lag in diagnostic testing can be catastrophic. That has been the case with the novel coronavirus, for which widespread testing was badly delayed due to the development of a flawed diagnostic test at the CDC. But the bigger problem wasn’t the glitch in the government’s assay; rather, it was the policy of centralizing testing at one federal lab. Centralizing, in short, just meant bottlenecking.

“Even if everything went perfectly, even if the CDC tests had rolled out perfectly, there was no way that the screening capacity in the U.S. was going to be robust enough to deal with a pandemic strain here in the U.S.,” says Scott Gottlieb, a physician and former commissioner of the FDA, which regulates such diagnostics. “You always had to get the academic labs [at universities] and the clinical labs in the game. And that takes time. So you needed to be working with them in January to get them ready for February and March.

“If we had the capacity in place in mid-February to test 100,000 samples a week,” says Gottlieb, “it could have made a very big difference.” Corwin agrees: “All the scenario planning around this type of virus was predicated on early testing and diagnosis.”

Which brings up something else we know: A plan is not a process. When I reach Bruce Gellin, the president of global immunization at the Sabin Vaccine Institute, he—like most everyone else in America—is under home quarantine, which has afforded him time to clean out his garage. There, under piles of Beanie Babies and other 1990s detritus, Gellin has found volumes of several of the federal government’s plans to fight a viral scourge. “We had a plandemic,” quips Gellin, a former deputy assistant secretary for Health and leader of HHS’s National Vaccine Program Office. In 2005, under the Bush administration, he led the creation of America’s first pandemic influenza preparedness and response plan.

This was the “bird flu” era, and federal policy makers were imagining the economic and social costs of quarantining huge swaths of the population, if it came to that. “One of the principles was outlining the backstops that needed to be in place to allow people to stay in place,” Gellin recalls. “How would a nurse be able to work if her school-age kids were home, for example? How would someone living hand-to-mouth not get kicked out of her house if she can’t work—or a homeowner not default on a mortgage? There is a huge cascade of stuff that has to happen if you’re going to force people to stay at home.” Such “community mitigation,” as they called it, was just part of the planning within the plan. In the era of COVID-19, we are all learning how essential such questions are.

Finally, the most powerful lesson of all¬ may come from witnessing government inaction in the face of a once-in-a-generation challenge—and knowing the cost of that paralysis.

After President George W. Bush tapped Michael Leavitt to succeed former Wisconsin Gov. Tommy Thompson as secretary of Health and Human Services in December 2004, Leavitt asked all of the agency’s operating and staff division heads to come over and brief him on their respective portfolios.

“He was trying to decide who to keep, maybe, and who not to keep,” says Stewart Simonson, then a former assistant secretary for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and now assistant director-general for the World Health Organization’s office at the United Nations. “And so I went over to brief on the preparedness and response portfolio, and then at the end of the meeting, I gave him two books: The Great Influenza—John Barry’s book on the 1918 flu epidemic—and the 9/11 Commission Report.

“And what I said is—something to the effect of that we know we will have another 1918. It’s inevitable. It’s just a matter of time. And if it happens while you’re secretary, and you’re not aware of the threat, this other book’s next volume will be about you.”