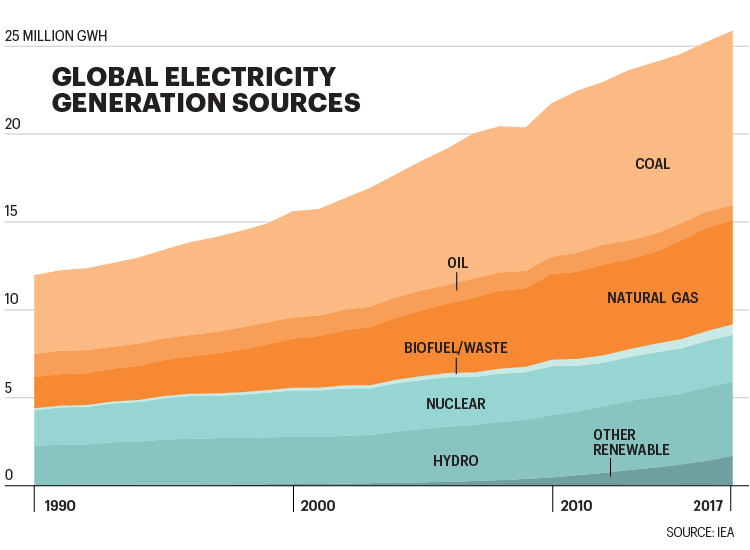

化石燃料行业面临着一个经典的商业问题:其他人已经想出更好的技术。在过去的十年里,工程技术革命推动太阳能电池板和风力涡轮机的价格足足下降了90%左右。在世界上大多数地区,清洁能源现已成为最便宜的发电方式。如今,蓄电池的价格正在沿着同样的曲线急转直下。就连对现代文化影响至深、消耗了大量化石燃料的汽车,也在迅速改变。开过特斯拉电动汽车的人都不会否认它是一台上乘的机器:速度快、运动机件少、安静而优雅。相比之下,隆隆作响的汽油车倒显得有点不合时宜。

面对严峻如斯的挑战,守成行业通常都会采取拖延时间的战术,寻求再维持10年或20年的盈利。对于长期雄踞美国经济核心位置的能源行业来说,这种过渡期显得尤为缓慢。忆往昔,无论是从木材到煤炭,还是从煤炭到石油,固定投资和既有的供应线意味着,这种转型期往往需要持续四五十年,甚至更长时间。距离化石燃料行业优雅离去的那一天,似乎还远着呢。

但化石燃料行业还面临着一个特别的问题:事实证明,其产品正在毁灭世界。

这听起来是不是有点夸张?去年冬天,向来对气候问题持激进立场的华尔街巨头摩根大通,为高端客户准备了一份研究报告。据英国媒体爆料,其经济学家团队在这份报告中详尽阐释当前的气候科学,并总结称:“我们不能排除灾难性后果,我们所熟知的人类生活将遭受严重威胁。”该报告援引国际货币基金组织(IMF)和联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)等机构的研究成果,直言不讳地指出,决策者别无选择,只能迫使能源领域逐步摈弃煤炭、石油和天然气,因为“一切如常”的气候政策“很可能会把地球推向数百万年未有之境地。”随着两极融化、海洋酸化,这个星球将越过无可挽回的临界点。“很明显,地球正处于一个不可持续的轨道上。”这份报告写道。“如果人类要生存下去,现有的能源体系就必须改变。”

换句话说,世界如何应对化石燃料行业的两大问题,将决定人类的未来。越来越明显的是,尽管政府在解决这些问题的竞赛中扮演着关键角色,但银行、保险商和资产管理公司的作用同样不可小觑。也就是说,华尔街和华盛顿需要齐头并进。所有利益攸关方,包括活动人士和金融家在内,正在达成一个共识:如果向清洁能源的过渡按照石油和煤炭游说团体乐见的速度进行,地球将会崩溃。

是的,我们无法阻止全球变暖。再也无力回天。但如果这种过渡发展得非常快,我们或许可以把它限制在人类文明得以延续的程度。早在1989年,我就为普通读者撰写了第一本谈论气候变化的著作。我可以告诉你,人类正处在一个前所未有的时刻。今天,要求采取紧急行动的呼声,正在不断冲撞一份旨在否认气候变化的脚本。它是石油行业自上世纪90年代以来精心培育的成果,而非常不幸的是,就连白宫也沦为了这份脚本的忠实拥趸。哪一种叙事获胜,不仅将决定这个星球的经济面貌,也将决定其真实景观——海平面上升多高,多少森林化为灰烬,多少人被迫离开家园,等等。改变气候是人类有史以来最大的“伟业”。现在,我们将一起见证人类能否卓有成效地应对自己造成的“烂摊子”。有一件事是肯定的: 除非商界接受挑战,否则成功的几率极其渺茫。

大约10年前,伦敦小型智库“碳追踪计划”的分析师发表报告,逐一阐释了气候危机的基本事实。化石燃料行业的储量清单中包含大量的碳。具体来说,该行业已经确定,并告知股东和监管机构它将燃烧的煤炭、天然气和石油储量,足以产生30,000亿吨碳,其表现形式就是二氧化碳。然而,全世界的科学家早已得出结论,要想实现各国政府设定的气候目标,人类最多只能再燃烧大约6,000亿吨碳。在过去十年,随着气候目标不断调整,这些数字有所波动,但基本比率保持不变:就本质而言,化石燃料行业的碳供应量远远超过大气的处理能力。

这个问题不仅事关地球上的生命,也会对资产负债表产生重大影响。如果你愿意的话,你可以把这种过剩供应称为“碳泡沫”。以目前的价格计算,它可能代表着价值20万亿美元、业已反映在能源公司市值中的化石燃料,但科学家指出,我们必须让这些化石燃料长眠于地下。(与此同时,原油价格的大幅下跌给大型石油公司带来了巨大的利润压力。这也是股市近期剧烈波动的原因之一。)马克·卡尼在3月卸任英国央行行长,出任联合国气候金融特使。相较于其他监管高官,他早就意识到了这种危险。2014年,他在伦敦劳合社告诉全球保险公司,他们过度地暴露于这些潜在搁浅资产的风险之下,这是极其危险的。

从2012年开始,世界各地的环保人士,包括本文作者在内,开始呼吁各大机构剥离化石燃料资产。起初,我们开展这场活动主要是基于道义方面的理由,早期的响应者大多是小型学院和宗教团体。但这一行动迅速形成声势,最终成为史上规模最大的反公司运动。根据Gofossilfree.org提供的数据,截至2019年12月,约有12万亿美元的捐赠基金和投资组合宣布撤离。一大原因是,聪明的投资者已经意识到,化石燃料类股票的市场表现落后于其他任何板块。

已经开始撤资的机构包括纽约市养老基金、英国一半的学院和大学、挪威主权财富基金(其资产总额超过1万亿美元,是全球最大的投资资本池)、洛克菲勒慈善基金(众所周知,该基金会源自这个星球上第一笔石油财富),以及庞大的加州大学体系。几乎每一天都有类似的公告。就在我撰写本文之际,推特上闪过这样一条消息:新西兰主要退休基金KiwiSavers也加入了这个行列。总的来说,这些撤资行动改变了对话,更不用说资金成本了:煤炭企业高管抱怨说,由于太多的基金撤资,现在几乎不可能筹集到资金。在去年的年报中,壳牌石油称撤资对其业务构成了重大风险。去年冬天,美国最受欢迎的选股人吉姆·克莱默在CNBC财经频道发疯似地谩骂道,化石燃料类股票已经赚不到钱了,因为“我们开始看到全世界都在撤资。”因此,化石燃料行业“正处于丧钟敲响的阶段。”他说。

但撤离的速度仍然不够快,无法达到缓解气候危机所需的科学目标。正如卡尼在最后一次以英国央行行长身份露面时所解释的那样,大型投资机构的视野往往为2至10年。“在这样一个视野范围,还会发生更多的极端天气事件,但等到极端天气事件变得如此普遍而明显时,一切都为时已晚。”

因此,活动人士再一次为撤资行动加码,这一次他们开始向金融机构本身施压,而不仅仅是化石燃料公司。我们发起了一场声势浩大的宣传攻势,敦促贝莱德、道富银行、摩根大通、美国银行、利宝互助保险和安达保险等金融大鳄终止所谓的“资金管道”。据悉,自2015年巴黎气候谈判结束以来,各大金融机构至少向化石燃料行业注入了2万亿美元贷款。

一方面,这看起来像是一场毫无胜算的圣战:毕竟,这些都是地球上最富有的机构;即使经历了2008年全球金融危机的洗礼,他们大多毫发无损,有些机构的规模甚至比以往任何时候都要大。他们难道还会怕一小撮衣冠不整的抗议者不成?

但另一方面,普罗大众越来越难以抑制对气候变化的愤怒情绪。特别是,随着人们逐渐意识到,化石燃料行业在很大程度上遮掩了他们早前对全球变暖的认知,这种怒火正在抵达顶点。根据耶鲁大学研究人员在去年冬天进行的一项民意调查,如果一位备受尊敬和喜爱的人士发出号召,五分之一的美国人准备“亲身参与非暴力的公民不服从活动,起身反抗那些正在导致全球变暖加剧的企业或政府活动。”有人猜测,这种情绪高度集中在城市和郊区地带,而美国的大多数财富恰恰聚集在这些地区。是的,特朗普或许坐拥美国选区图上那些深红地区的支持,但资金地图却向另一个方向倾斜。金融机构需要对自己的客户保持一点警惕心:毕竟,有很多大通信用卡握在那些开始关心全球变暖问题的民众手中。

事实上,这些机构并没有抵抗多久就开始屈服,这一点颇具启发性。在这场由塞拉俱乐部和“绿色和平”等重量级非政府组织参与的“终止资金管道”运动启动初期,一群抗议者聚集在利宝互助保险的波士顿总部外面,高声谴责这家保险巨头继续大举投资化石燃料项目,哪怕该公司正在终止加州的投保业务——因为气候变化引发的森林大火,使得承保加州房屋的风险太大。仅仅几周后,利宝互助保险就开始让步,在去年12月宣布了一项新政策,拟定限制对煤炭项目和加拿大油砂田的投资。很快,像哈特福保险这类金融机构也纷纷效仿。就在同月,高盛集团也宣布将限制对北极地区化石燃料项目的融资规模。

今年1月出现了一个重大突破。华尔街巨头贝莱德宣布,准备将可持续性置于其投资战略的核心地位。要知道,贝莱德是全球最大的金融机构,旗下管理的资产高达7.4万亿美元,它也是这场新兴运动着力攻克的关键目标。首席执行官劳伦斯·芬克在一封致投资者信中表示:“与气候变化风险相关的证据,正在迫使投资者重新评估现代金融的核心假设。”芬克说,贝莱德将投票反对那些不致力于实现可持续发展目标的管理团队,他的公司将敦促企业披露计划,以确保“其业务运营有助于推动巴黎协定目标的完全实现,即将本世纪全球平均气温上升幅度控制在2摄氏度以内。”由于贝莱德是许多上市公司最大的单一股东,这种威胁的分量是实实在在的。

当然,对于所有正在思考气候危机的企业来说,这只是等式的一半。另一半则是积极向上的:必须设法打造,并资助人类历史上最大规模的产业转型。“实现净零排放需要整个经济完成转型。”2月底向伦敦金融城发表告别演说时,卡尼这样说道。“每家公司、每家银行、每家保险公司和投资者都必须调整其业务模式。倘如此,这一事关人类存亡的风险,有可能演变为我们这个时代最大的商业机会。”

仅举一个小例子。纽约市在去年年底颁布法令,要求五大自治区的所有大型建筑到2030年必须将碳排放量减少40%。这是非常必要的,因为面积超过25,000平方英尺、仅占所有建筑2%的大楼贡献了全市大约一半排放量。但这个目标显然不容易实现。城市绿色委员会首席执行官约翰·曼迪克说:“这项法律可能是纽约房地产行业在我们有生之年面临的最大考验。”如果房东没有达标怎么办?他就不得不为多排放的每吨碳支付高达268美元的罚金。对一些大业主来说,这可能意味着100万美元。但另一方面,试想一下这些维修带来的收获:一支受过绝缘和暖通空调检修培训的全新劳动力队伍。这在技术上是完全可以实现的。正如卡内基梅隆大学教授薇薇安·洛夫内斯向记者解释的那样,“一些老机械系统的运行效率只有区区50%,而市场上还有一些运行效率将达到95%的设备。锅炉、制冷机、组合式空调机组和控制系统都有很大的升级空间,所有这些还仅仅是建筑硬件方面的。”

不妨想象一下,为这种改造融资能赚到多少钱。然后再想想,一旦完成这些升级,你可以节省多少钱:如果你能够少用40%的能源,年复一年,你的损益表就会突然变得好看起来。是的,能源效率是那种可以给自己买单的革命之一。

但如果所有这些措施无法迅速到位,那真的就不值得做了。这就是气候变化的症结所在:留给人类影响结果的杠杆期,似乎只会持续到未来几年。2018年10月,联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会发表了最近一次情况更新。科学家们在这份报告中警告称,倘若世界能源体系无法在2020年代实现根本变革——根据他们的定义,这种变革意味着将碳排放量减少一半——我们就再也不必对实现必要的气候目标抱有任何幻想了。

从长远来看,这将是相当昂贵的。在上述报告发布的同一个月,英国经济学家试图计算,如果根据目前的发展轨迹,全球变暖幅度到本世纪末达到3.7摄氏度左右,世界经济将承受多大的损失?他们的计算结果是:551万亿美元。这个数字远远高于地球现有的财富总额。

我们面临的选项再清晰不过:要么抓住现在的投资机会,获得丰厚的回报,并顺便拯救人类,要么在未来承担不可估量的损失。精明的金融家应该都知道,哪一种才是正确的选择。(财富中文网)

本文作者比尔·麦克基本(Bill McKibben)是一位作家、环保主义者和活动家,其著作包括《自然的终结》(The End of Nature , 1989年出版)和《强弩之末》(Falter , 2019年出版)。他也是国际气候运动组织350.org的联合创始人和高级顾问。

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年4月刊,标题为《终止对化石燃料的投资》。

译者:任文科

化石燃料行业面临着一个经典的商业问题:其他人已经想出更好的技术。在过去的十年里,工程技术革命推动太阳能电池板和风力涡轮机的价格足足下降了90%左右。在世界上大多数地区,清洁能源现已成为最便宜的发电方式。如今,蓄电池的价格正在沿着同样的曲线急转直下。就连对现代文化影响至深、消耗了大量化石燃料的汽车,也在迅速改变。开过特斯拉电动汽车的人都不会否认它是一台上乘的机器:速度快、运动机件少、安静而优雅。相比之下,隆隆作响的汽油车倒显得有点不合时宜。

面对严峻如斯的挑战,守成行业通常都会采取拖延时间的战术,寻求再维持10年或20年的盈利。对于长期雄踞美国经济核心位置的能源行业来说,这种过渡期显得尤为缓慢。忆往昔,无论是从木材到煤炭,还是从煤炭到石油,固定投资和既有的供应线意味着,这种转型期往往需要持续四五十年,甚至更长时间。距离化石燃料行业优雅离去的那一天,似乎还远着呢。

但化石燃料行业还面临着一个特别的问题:事实证明,其产品正在毁灭世界。

这听起来是不是有点夸张?去年冬天,向来对气候问题持激进立场的华尔街巨头摩根大通,为高端客户准备了一份研究报告。据英国媒体爆料,其经济学家团队在这份报告中详尽阐释当前的气候科学,并总结称:“我们不能排除灾难性后果,我们所熟知的人类生活将遭受严重威胁。”该报告援引国际货币基金组织(IMF)和联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)等机构的研究成果,直言不讳地指出,决策者别无选择,只能迫使能源领域逐步摈弃煤炭、石油和天然气,因为“一切如常”的气候政策“很可能会把地球推向数百万年未有之境地。”随着两极融化、海洋酸化,这个星球将越过无可挽回的临界点。“很明显,地球正处于一个不可持续的轨道上。”这份报告写道。“如果人类要生存下去,现有的能源体系就必须改变。”

换句话说,世界如何应对化石燃料行业的两大问题,将决定人类的未来。越来越明显的是,尽管政府在解决这些问题的竞赛中扮演着关键角色,但银行、保险商和资产管理公司的作用同样不可小觑。也就是说,华尔街和华盛顿需要齐头并进。所有利益攸关方,包括活动人士和金融家在内,正在达成一个共识:如果向清洁能源的过渡按照石油和煤炭游说团体乐见的速度进行,地球将会崩溃。

是的,我们无法阻止全球变暖。再也无力回天。但如果这种过渡发展得非常快,我们或许可以把它限制在人类文明得以延续的程度。早在1989年,我就为普通读者撰写了第一本谈论气候变化的著作。我可以告诉你,人类正处在一个前所未有的时刻。今天,要求采取紧急行动的呼声,正在不断冲撞一份旨在否认气候变化的脚本。它是石油行业自上世纪90年代以来精心培育的成果,而非常不幸的是,就连白宫也沦为了这份脚本的忠实拥趸。哪一种叙事获胜,不仅将决定这个星球的经济面貌,也将决定其真实景观——海平面上升多高,多少森林化为灰烬,多少人被迫离开家园,等等。改变气候是人类有史以来最大的“伟业”。现在,我们将一起见证人类能否卓有成效地应对自己造成的“烂摊子”。有一件事是肯定的: 除非商界接受挑战,否则成功的几率极其渺茫。

大约10年前,伦敦小型智库“碳追踪计划”的分析师发表报告,逐一阐释了气候危机的基本事实。化石燃料行业的储量清单中包含大量的碳。具体来说,该行业已经确定,并告知股东和监管机构它将燃烧的煤炭、天然气和石油储量,足以产生30,000亿吨碳,其表现形式就是二氧化碳。然而,全世界的科学家早已得出结论,要想实现各国政府设定的气候目标,人类最多只能再燃烧大约6,000亿吨碳。在过去十年,随着气候目标不断调整,这些数字有所波动,但基本比率保持不变:就本质而言,化石燃料行业的碳供应量远远超过大气的处理能力。

这个问题不仅事关地球上的生命,也会对资产负债表产生重大影响。如果你愿意的话,你可以把这种过剩供应称为“碳泡沫”。以目前的价格计算,它可能代表着价值20万亿美元、业已反映在能源公司市值中的化石燃料,但科学家指出,我们必须让这些化石燃料长眠于地下。(与此同时,原油价格的大幅下跌给大型石油公司带来了巨大的利润压力。这也是股市近期剧烈波动的原因之一。)马克·卡尼在3月卸任英国央行行长,出任联合国气候金融特使。相较于其他监管高官,他早就意识到了这种危险。2014年,他在伦敦劳合社告诉全球保险公司,他们过度地暴露于这些潜在搁浅资产的风险之下,这是极其危险的。

从2012年开始,世界各地的环保人士,包括本文作者在内,开始呼吁各大机构剥离化石燃料资产。起初,我们开展这场活动主要是基于道义方面的理由,早期的响应者大多是小型学院和宗教团体。但这一行动迅速形成声势,最终成为史上规模最大的反公司运动。根据Gofossilfree.org提供的数据,截至2019年12月,约有12万亿美元的捐赠基金和投资组合宣布撤离。一大原因是,聪明的投资者已经意识到,化石燃料类股票的市场表现落后于其他任何板块。

已经开始撤资的机构包括纽约市养老基金、英国一半的学院和大学、挪威主权财富基金(其资产总额超过1万亿美元,是全球最大的投资资本池)、洛克菲勒慈善基金(众所周知,该基金会源自这个星球上第一笔石油财富),以及庞大的加州大学体系。几乎每一天都有类似的公告。就在我撰写本文之际,推特上闪过这样一条消息:新西兰主要退休基金KiwiSavers也加入了这个行列。总的来说,这些撤资行动改变了对话,更不用说资金成本了:煤炭企业高管抱怨说,由于太多的基金撤资,现在几乎不可能筹集到资金。在去年的年报中,壳牌石油称撤资对其业务构成了重大风险。去年冬天,美国最受欢迎的选股人吉姆·克莱默在CNBC财经频道发疯似地谩骂道,化石燃料类股票已经赚不到钱了,因为“我们开始看到全世界都在撤资。”因此,化石燃料行业“正处于丧钟敲响的阶段。”他说。

但撤离的速度仍然不够快,无法达到缓解气候危机所需的科学目标。正如卡尼在最后一次以英国央行行长身份露面时所解释的那样,大型投资机构的视野往往为2至10年。“在这样一个视野范围,还会发生更多的极端天气事件,但等到极端天气事件变得如此普遍而明显时,一切都为时已晚。”

因此,活动人士再一次为撤资行动加码,这一次他们开始向金融机构本身施压,而不仅仅是化石燃料公司。我们发起了一场声势浩大的宣传攻势,敦促贝莱德、道富银行、摩根大通、美国银行、利宝互助保险和安达保险等金融大鳄终止所谓的“资金管道”。据悉,自2015年巴黎气候谈判结束以来,各大金融机构至少向化石燃料行业注入了2万亿美元贷款。

一方面,这看起来像是一场毫无胜算的圣战:毕竟,这些都是地球上最富有的机构;即使经历了2008年全球金融危机的洗礼,他们大多毫发无损,有些机构的规模甚至比以往任何时候都要大。他们难道还会怕一小撮衣冠不整的抗议者不成?

但另一方面,普罗大众越来越难以抑制对气候变化的愤怒情绪。特别是,随着人们逐渐意识到,化石燃料行业在很大程度上遮掩了他们早前对全球变暖的认知,这种怒火正在抵达顶点。根据耶鲁大学研究人员在去年冬天进行的一项民意调查,如果一位备受尊敬和喜爱的人士发出号召,五分之一的美国人准备“亲身参与非暴力的公民不服从活动,起身反抗那些正在导致全球变暖加剧的企业或政府活动。”有人猜测,这种情绪高度集中在城市和郊区地带,而美国的大多数财富恰恰聚集在这些地区。是的,特朗普或许坐拥美国选区图上那些深红地区的支持,但资金地图却向另一个方向倾斜。金融机构需要对自己的客户保持一点警惕心:毕竟,有很多大通信用卡握在那些开始关心全球变暖问题的民众手中。

事实上,这些机构并没有抵抗多久就开始屈服,这一点颇具启发性。在这场由塞拉俱乐部和“绿色和平”等重量级非政府组织参与的“终止资金管道”运动启动初期,一群抗议者聚集在利宝互助保险的波士顿总部外面,高声谴责这家保险巨头继续大举投资化石燃料项目,哪怕该公司正在终止加州的投保业务——因为气候变化引发的森林大火,使得承保加州房屋的风险太大。仅仅几周后,利宝互助保险就开始让步,在去年12月宣布了一项新政策,拟定限制对煤炭项目和加拿大油砂田的投资。很快,像哈特福保险这类金融机构也纷纷效仿。就在同月,高盛集团也宣布将限制对北极地区化石燃料项目的融资规模。

今年1月出现了一个重大突破。华尔街巨头贝莱德宣布,准备将可持续性置于其投资战略的核心地位。要知道,贝莱德是全球最大的金融机构,旗下管理的资产高达7.4万亿美元,它也是这场新兴运动着力攻克的关键目标。首席执行官劳伦斯·芬克在一封致投资者信中表示:“与气候变化风险相关的证据,正在迫使投资者重新评估现代金融的核心假设。”芬克说,贝莱德将投票反对那些不致力于实现可持续发展目标的管理团队,他的公司将敦促企业披露计划,以确保“其业务运营有助于推动巴黎协定目标的完全实现,即将本世纪全球平均气温上升幅度控制在2摄氏度以内。”由于贝莱德是许多上市公司最大的单一股东,这种威胁的分量是实实在在的。

当然,对于所有正在思考气候危机的企业来说,这只是等式的一半。另一半则是积极向上的:必须设法打造,并资助人类历史上最大规模的产业转型。“实现净零排放需要整个经济完成转型。”2月底向伦敦金融城发表告别演说时,卡尼这样说道。“每家公司、每家银行、每家保险公司和投资者都必须调整其业务模式。倘如此,这一事关人类存亡的风险,有可能演变为我们这个时代最大的商业机会。”

仅举一个小例子。纽约市在去年年底颁布法令,要求五大自治区的所有大型建筑到2030年必须将碳排放量减少40%。这是非常必要的,因为面积超过25,000平方英尺、仅占所有建筑2%的大楼贡献了全市大约一半排放量。但这个目标显然不容易实现。城市绿色委员会首席执行官约翰·曼迪克说:“这项法律可能是纽约房地产行业在我们有生之年面临的最大考验。”如果房东没有达标怎么办?他就不得不为多排放的每吨碳支付高达268美元的罚金。对一些大业主来说,这可能意味着100万美元。但另一方面,试想一下这些维修带来的收获:一支受过绝缘和暖通空调检修培训的全新劳动力队伍。这在技术上是完全可以实现的。正如卡内基梅隆大学教授薇薇安·洛夫内斯向记者解释的那样,“一些老机械系统的运行效率只有区区50%,而市场上还有一些运行效率将达到95%的设备。锅炉、制冷机、组合式空调机组和控制系统都有很大的升级空间,所有这些还仅仅是建筑硬件方面的。”

不妨想象一下,为这种改造融资能赚到多少钱。然后再想想,一旦完成这些升级,你可以节省多少钱:如果你能够少用40%的能源,年复一年,你的损益表就会突然变得好看起来。是的,能源效率是那种可以给自己买单的革命之一。

但如果所有这些措施无法迅速到位,那真的就不值得做了。这就是气候变化的症结所在:留给人类影响结果的杠杆期,似乎只会持续到未来几年。2018年10月,联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会发表了最近一次情况更新。科学家们在这份报告中警告称,倘若世界能源体系无法在2020年代实现根本变革——根据他们的定义,这种变革意味着将碳排放量减少一半——我们就再也不必对实现必要的气候目标抱有任何幻想了。

从长远来看,这将是相当昂贵的。在上述报告发布的同一个月,英国经济学家试图计算,如果根据目前的发展轨迹,全球变暖幅度到本世纪末达到3.7摄氏度左右,世界经济将承受多大的损失?他们的计算结果是:551万亿美元。这个数字远远高于地球现有的财富总额。

我们面临的选项再清晰不过:要么抓住现在的投资机会,获得丰厚的回报,并顺便拯救人类,要么在未来承担不可估量的损失。精明的金融家应该都知道,哪一种才是正确的选择。(财富中文网)

本文作者比尔·麦克基本(Bill McKibben)是一位作家、环保主义者和活动家,其著作包括《自然的终结》(The End of Nature , 1989年出版)和《强弩之末》(Falter , 2019年出版)。他也是国际气候运动组织350.org的联合创始人和高级顾问。

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年4月刊,标题为《终止对化石燃料的投资》。

译者:任文科

THE FOSSIL FUEL INDUSTRY faces a classic business problem: Someone else has come up with a better technology. Over the past decade, engineering advances have helped drive down the price of solar panels and wind turbines by some 90%. Clean energy is now the cheapest way to generate power in most of the world. And today, storage batteries are on the same plummeting price curve—so that, increasingly, the sun’s habit of going down at night is no big deal. Even the car, which has helped define our culture and consumes vast quantities of fossil fuel, is changing fast. No honest person who has driven a Tesla will dispute that it’s a superior machine: fast, with few moving parts, and a quiet elegance that makes a rumbling muscle car seem more than a little old-fashioned.

Faced with that kind of challenge, incumbent industries usually play for time, trying to eke out another decade or two of profits before wandering off to a well-appointed retirement home. For the energy industry—at the heart of our economy for so long—transition periods have been particularly slow. Fixed investments and established supply lines mean that, in the past, converting from wood to coal or coal to oil has played out over 40 or 50 years or more. Plenty of time for a nice wind-down.

But the fossil fuel industry also faces a decidedly novel business problem: It turns out that its product is destroying the world.

Does that sound like hyperbole? This winter, a team of economists at that radical outpost known as JPMorgan Chase prepared a report for high-end clients that eventually leaked to the British press. It explained the current science in great detail and concluded: “We cannot rule out catastrophic outcomes where human life as we know it is threatened.” Quoting many groups from the International Monetary Fund to the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the report said policymakers have no choice but to force the transition off coal, oil, and gas because a business-as-usual climate policy “would likely push the earth to a place that we haven’t seen for many millions of years,” sweeping the planet past irrevocable tipping points as the poles melt and oceans acidify. “It is clear that the Earth is on an unsustainable trajectory,” it said. “Something will have to change at some point if the human race is going to survive.”

How the world deals with the fossil fuel industry’s two existential problems, in other words, will define humankind’s future. And it has become increasingly clear that while government plays a key role in the race to solve these problems, so too do banks, insurance companies, and asset managers: Wall Street as well as Washington, if you like shorthand. There’s an emerging agreement among all parties, activists and financiers alike, that if the transition to clean energy goes at the pace that the oil and coal lobbyists would like, the planet will break.

If that transition instead goes unnaturally fast—well, we can’t stop global warming. Not anymore. But we might limit it to the point at which civilizations endure. I wrote the first book for a general audience on this topic back in 1989, and I can tell you we are at a point we have never seen before. The demand for urgent action is today crashing up against a climate denial script that has been carefully nurtured by the oil industry since the 1990s and is now the reigning wisdom at the White House. Which narrative emerges victorious will not only determine the financial landscape of the planet, but it will also determine the literal landscape— how high the seas rise, how many forests burn, how many people must leave their homes. Changing the climate is the biggest thing humans have ever done, and now we’ll see how effectively we can respond to a mess of our own making. One thing is for certain: The chances of success are very low unless the business world embraces the challenge.

ABOUT A DECADE AGO, analysts at a small London think tank, the Carbon Tracker Initiative, published a report laying out the essential underlying facts of the climate crisis. The fossil fuel industry had in its inventory of reserves a vast quantity of carbon: that is, the coal and gas and oil deposits it had identified and told shareholders and regulators it would burn—enough to produce almost 3,000 gigatons of carbon in the form of carbon dioxide. The world’s scientists, however, had concluded that we could really only burn about 600 gigatons more and have any hope of meeting the climate targets that the world’s governments had set. The numbers have fluctuated some over the decade as those targets have shifted, but the ratios remain unchanged: In essence, the industry has far, far more supply than the atmosphere can deal with.

And that’s a problem not just for life on earth but also for balance sheets. You could call that excess supply a carbon bubble if you’d like—at current prices it may represent something like $20 trillion worth of fossil fuel that is already reflected in the value of these firms but that scientists say we must keep in the ground. (The dramatic decline in crude prices that has helped rock the stock market of late, meanwhile, has put a profit squeeze on Big Oil.) Mark Carney, who just stepped down as governor of the Bank of England in March to become the UN’s climate finance envoy, was far ahead of other regulators in recognizing the danger, telling the world’s insurers at Lloyds of London in 2014 that they were dangerously overexposed to the risk of these potentially stranded assets.

Beginning in 2012, environmental activists around the world, myself included, began calling for institutions to divest their holdings in fossil fuels. At first, we campaigned mostly on moral grounds, and the early respondents were small colleges and religious denominations. But the push quickly gained steam, becoming the biggest anticorporate campaign in history. As of December 2019, some $12 trillion worth of endowments and portfolios had divested, according to Gofossilfree.org, in part because the smart money had come to realize that the fossil fuel sector was lagging everything else in the market.

The institutions that have begun to divest include New York City’s pension fund, half of the colleges and universities in the U.K., the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund (at more than $1 trillion, the biggest pool of investment capital on the planet), the Rockefeller charities (which descend from the planet’s first oil fortune), and the vast University of California system. Not a day goes by without some new announcement: As I was writing this piece, Twitter flashed the news that KiwiSavers, the primary retirement fund in New Zealand, had joined the ranks. Together, divestment has changed the dialogue, not to mention the cost of capital: Coal executives complain it’s nearly impossible to raise money because so many funds have divested, and in last year’s annual report, Shell Oil called divestment a material risk to its business. As America’s favorite stock picker, Jim Cramer, put it in a typically manic diatribe on CNBC this winter, there’s no money to be made anymore in fossil fuel stocks because “we’re starting to see divestment all over the world.” As a result, he said, fossil fuels were “in the death knell phase.”

But that phase-out still isn’t coming fast enough to meet the scientific targets necessary to mitigate the climate crisis. As Carney explained in one of his last appearances as BofE governor in December, big institutional investors tended to have horizons of two to 10 years. “In those horizons, there will be more extreme weather events, but by the time that the extreme events become so prevalent and so obvious, it’s too late to do anything about it.”

As a result, campaigners have expanded the divestment drive one ring out, this time pressuring the financial institutions themselves instead of just the fossil fuel companies. We have mounted a fast-growing crusade to get the BlackRocks and the State Streets, the JPMorgan Chases and BofAs, the Liberty Mutuals and the Chubbs to end what they call a “money pipeline” that has funneled at least $2 trillion in loans to the fossil fuel industry since the end of the Paris climate talks in 2015.

On the one hand, it may seem like an unlikely crusade: These are, after all, the richest institutions on planet Earth; even after the global financial crisis of 2008 they mostly emerged unscathed and, in some cases, bigger than ever. Do they have anything much to fear from scruffy protesters?

But the anger of the general public over climate change is reaching a crescendo, especially as people have come to understand the degree to which the fossil fuel industry covered up its early knowledge of global warming. This winter, a poll conducted by Yale researchers found that fully a fifth of Americans were ready to “personally engage in nonviolent civil disobedience” against “corporate or government activities that make global warming worse,” if a person they liked and respected asked them to. One guesses that such sentiment is highly concentrated in precisely the urban and suburban precincts where American money is highly concentrated—Trump may own the bright-red electoral map of the U.S., but the money map tilts in the other direction. And financial institutions need to be a little wary of their customers: There are a lot of Chase credit cards in the hands of people who have come to care about global warming.

In fact, the speed with which these institutions have begun to bend is instructive. Early on in this new Stop the Money Pipeline campaign—which includes big NGOs like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace—protesters gathered outside Liberty Mutual’s Boston headquarters, pointing out that the insurance giant was continuing to invest heavily in fossil fuel projects, even as it was cutting off policyholders in California because climate-fueled wildfires were making their homes too risky to underwrite. And it was only a matter of weeks before Liberty Mutual began to buckle, announcing a policy in December that would restrict its investment in coal and in Canada’s dirty tar sands oil complex. Others like the Hartford soon followed, and that same month even Goldman Sachs proclaimed that it would restrict financing for fossil fuel projects in the Arctic.

A significant breakthrough came in January, when Wall Street behemoth BlackRock—the biggest financial player of all, with $7.4 trillion in assets under management and a key target of the emerging campaign—announced that it was going to put sustainability at the center of its investment strategy. In a letter to investors, CEO Larry Fink said, “The evidence on climate risk is compelling investors to reassess core assumptions about modern finance.” Fink said that BlackRock would vote against management teams that weren’t working toward sustainability goals, and his firm would press companies to disclose plans “for operating under a scenario where the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to less than two degrees is fully realized.” And since BlackRock is the biggest single stockholder for many public companies, the threat comes with real weight.

OF COURSE, this is only half the equation for businesses thinking about the climate crisis. The other half is all upside: Someone is going to have to build—and finance—the most massive industrial transition in human history. “Achieving net zero emissions will require a whole-economy transition,” Carney said in his valedictory speech to the City of London in late February. “Every company, every bank, every insurer, and investor will have to adjust its business model. This could turn an existential risk into the greatest commercial opportunity of our time.”

Consider just one small example: Late last year, New York City decreed that all big buildings in the five boroughs needed to cut their carbon emissions 40% by 2030. That’s necessary because the 2% of buildings over 25,000 square feet contribute about half the city’s emissions. Meeting the target clearly won’t be easy. As the CEO of the Urban Green Council, John Mandyck, said, “This law could possibly be the largest disruption in our lifetime for the real estate industry in New York City.” You’re a landlord who misses your target? The fines run up to $268 a ton of carbon, which could mean a million dollars for some big property owners. But, on the other hand, think of the money to be made from those repairs: a whole new workforce trained in insulation or overhauling HVAC. It’s all technically achievable. As Vivian Loftness, a Carnegie Mellon professor, explained to reporters, “We’ve got [older] mechanical systems that are running at 50% efficiency, where there’s things on the market that will run at 95% efficiency. We’ve got a lot of room for upgrades for boilers and chillers, air-handling units, control systems— there’s so much room in just the hardware of buildings.”

Imagine the money to be made from financing that kind of overhaul. And then think of the money to be saved once you have completed the upgrades: If you’re using 40% less energy, year after year, you have suddenly found a remarkable boost to your P&L. Energy efficiency is one of those revolutions that can pay for itself.

But none of it is really worth doing unless it can be done fast. That’s the rub with climate change: Our period of leverage to affect the outcome seems to stretch only a few years into the future. The scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued their most recent update in October of 2018, cautioning that unless fundamental transformation of our energy system took place in the decade of the 2020s—and they defined that transformation as cutting carbon emissions in half—we could kiss goodbye any hope of meeting the necessary climate targets.

And that would be, in the long run, rather expensive. In the same month as that IPCC report, British economists attempted to calculate the damage that would come from global warming that reached about 3.7 degrees Celsius by century’s end, which is in line with our current trajectory. Their figure? $551 trillion. Which is significantly more money than currently exists on planet Earth.

Our options are clear: Invest now with the opportunity to earn a nice return (and save humanity in the bargain), or take unfathomable losses down the line. The correct choice should be obvious to any smart financier.

Bill McKibben is an author, environmentalist, and activist whose books include The End of Nature (1989) and Falter (2019). He is a cofounder and senior adviser at 350.org, an international climate campaign organization.

A version of this article appears in the April 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline “Putting the Money Squeeze on Fossil Fuels.”