本文是《财富》杂志《特别报道:面临环境危机的商业》组文之一,与普利策危机报道中心合作发表。摄影:塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶

在马来西亚北部的一处山坡上,一座大型露天厂房矗立在油棕榈树和橡胶树之间。这是生物降解公司BioGreen Frontier设在Bukit Selambau村的再生资源回收工厂,去年11月投产。1月一个骄阳火辣的下午,沙希德·阿里刚刚开始了第一周的工作。他分开双脚,站在生产线尽头向下倾斜的传送带旁,脚边的白色湿软塑料丝深及膝盖。在他周围,更多的细丝从传送带上落下,像雪片一样飘散到地面上。

回收过程中,阿里一直在这堆塑料细丝中挑拣着看起来褪色或者脏了的不合格品。虽然这看起来很累,但阿里说这已经比他上一份工作好多了。此前他在附近的一家纺织厂叠床单,工资也比现在低得多。如今,如果吃的节省一点儿,就能存下钱来。他的时薪略高于1美元,每个月可以向父母和六个兄弟姐妹寄250美元,他们住在4300多公里外的巴基斯坦白沙瓦。24岁的阿里,身材矮胖,留着络腮胡子,戴着眼镜,脸上露出轻松的微笑。他说:“我听说这里招工,就赶紧跑来应聘了。”不过,他每天要工作12个小时,每周工作七天。“如果我休息一天,就会少一天的工资。” 阿里说。

在这座厂房中有几百个大包,堆了差不多有18米高,每个包里都塞满了几周前人们丢弃的塑料外包装和塑料袋。上面的地址标签清楚地指明了它们的来源地。可以看到加州半月湾一个家庭丢弃的厕纸外包装,在埃尔帕索打包。还可以看到聚合物薄膜,来自功能饮料厂商红牛设在圣莫妮卡的总部。

阿里所在的这类工厂是这些废弃物最终的归宿,它们飘洋过海,来到1.2万公里外这个遥远的角落,这首先说明全球资源回收经济和人类对塑料依赖之间存在的巨大差距。这个生态系统严重失灵,甚至已经濒临崩溃。全世界每年都会生产不计其数的塑料,其中约90%最终都没有得到回收利用,而是被烧掉、埋掉或者扔掉了。

而支持塑料回收利用的消费者越来越多,在数以百万计的家庭里,把酸奶盒、果汁瓶放进蓝色垃圾桶已经成了体现环保信仰的行为。但这种信仰也就到此为止。塑料物品每年都如同潮水般涌进回收行业,而且它们越来越有可能原封不动地被退出来,成为一个瘫痪市场的“受害者”。由于经济性太差,消费者眼中(而且业界宣称)的许多“可回收”产品实际上并非如此。随着石油和天然气价格接近20年来的最低点(这在很大程度上要归功于压裂开采技术革命),出现了所谓的新塑料,也就是一种源于石油原料的产品,其售价和获取难度要远低于可回收材料。对于直到现在仍只是勉强生存的资源回收行业来说,这种无法预见的变化无异于毁灭性的打击。绿色和平组织的全球塑料行动负责人格拉汉姆·福布斯说:“全球废品贸易实际上已经中断。我们坐拥大堆塑料,却无处可送,也无法处理。”

对于如此巨大的超负荷所引发的矛盾,业界和政府再也不能视而不见。这个矛盾源于塑料的盈利能力和用处及其对公众健康和环境的威胁,而且几乎没有什么地方能比马来西亚更能体现这种矛盾。在这里,超低的工资、便宜的土地以及仍在形成的监管气候吸引企业主建立了几百家回收工厂,这是他们为保持盈利的最后一搏。我和摄影师塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶走过了马来西亚各地,清楚地看到了回收利用塑料的实际经济和环境成本。我们在10天时间里走访了10家回收工厂,其中一些,包括BioGreen Frontier的运营都没有官方备案,所以有停工风险,而他们处理的是一船船来自世界各地的废品。我们还看到了塑料经济崩溃后对垃圾场、集装箱码头、家庭以及广阔海洋的影响。

过去50年塑料的发展呈直线上升态势,理由很充分,那就是它们便宜、轻便而且基本上不会损坏。在1967年的电影《毕业生》(The Graduate)中,后来的导师对紧张兮兮的年轻人本杰明·布拉多克(达斯汀·霍夫曼饰)说:“塑料非常有前途。”基于这样的提点来采取行动有可能产生巨大收益。塑料的全球年产量从1970年的2500万吨飙升至2018年的4亿吨以上。

塑料泛滥的背后是巨大的经济利益——英国数据分析机构Business Research Co.指出,去年全球塑料市场的价值约为1万亿美元。2000年以来塑料需求已经翻了一番,而且到2050年可能再增长一倍。塑料行业组织美国化学理事会的成员包括陶氏化学、杜邦、雪佛龙和埃克森美孚等主要厂商。该组织负责塑料市场的董事总经理基思·克里斯特曼说:“在世界各地,需要提高生活质量的中产阶层正在不断增多。塑料已然成为人们生活的一部分。”大家可以看到,不光是矿泉水瓶和三明治包装袋用塑料,其他含有塑料的东西不胜枚举,比如运动衫、湿纸巾、建筑隔音材料和墙板、口香糖和茶包。

关于碳排放的争论往往会掩盖人们对塑料的担心。但这两个问题紧密相连,因为塑料生产本身就会排放数量可观的温室气体。现在世界已经充分认识到了塑料危机。海龟被塑料吸管噎住,死去鲸鱼肚子里塞满塑料垃圾的图片早已广为流传——它们的背后是每年流入海洋的800万吨塑料(联合国环境规划署估算,到2050年海洋中的塑料数量将超过鱼类)。人类不可避免的会受到影响。世界自然基金会资助的研究显示,每位美国人平均每星期通过食物至少会吃下去一茶匙的塑料,差不多相当于一张信用卡,由此产生的健康问题还无法预测。

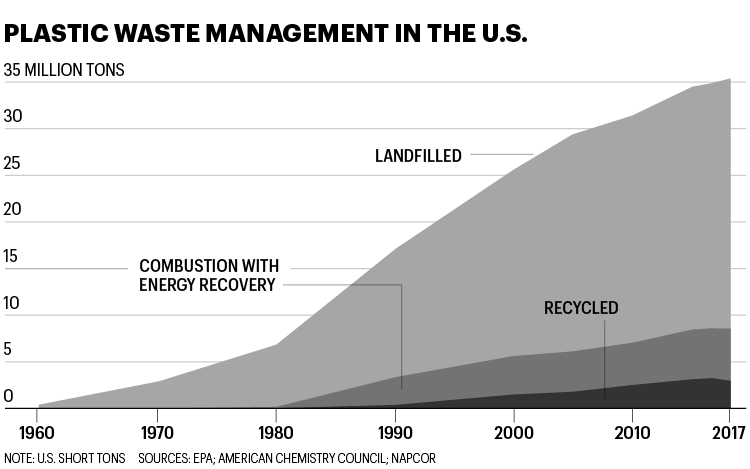

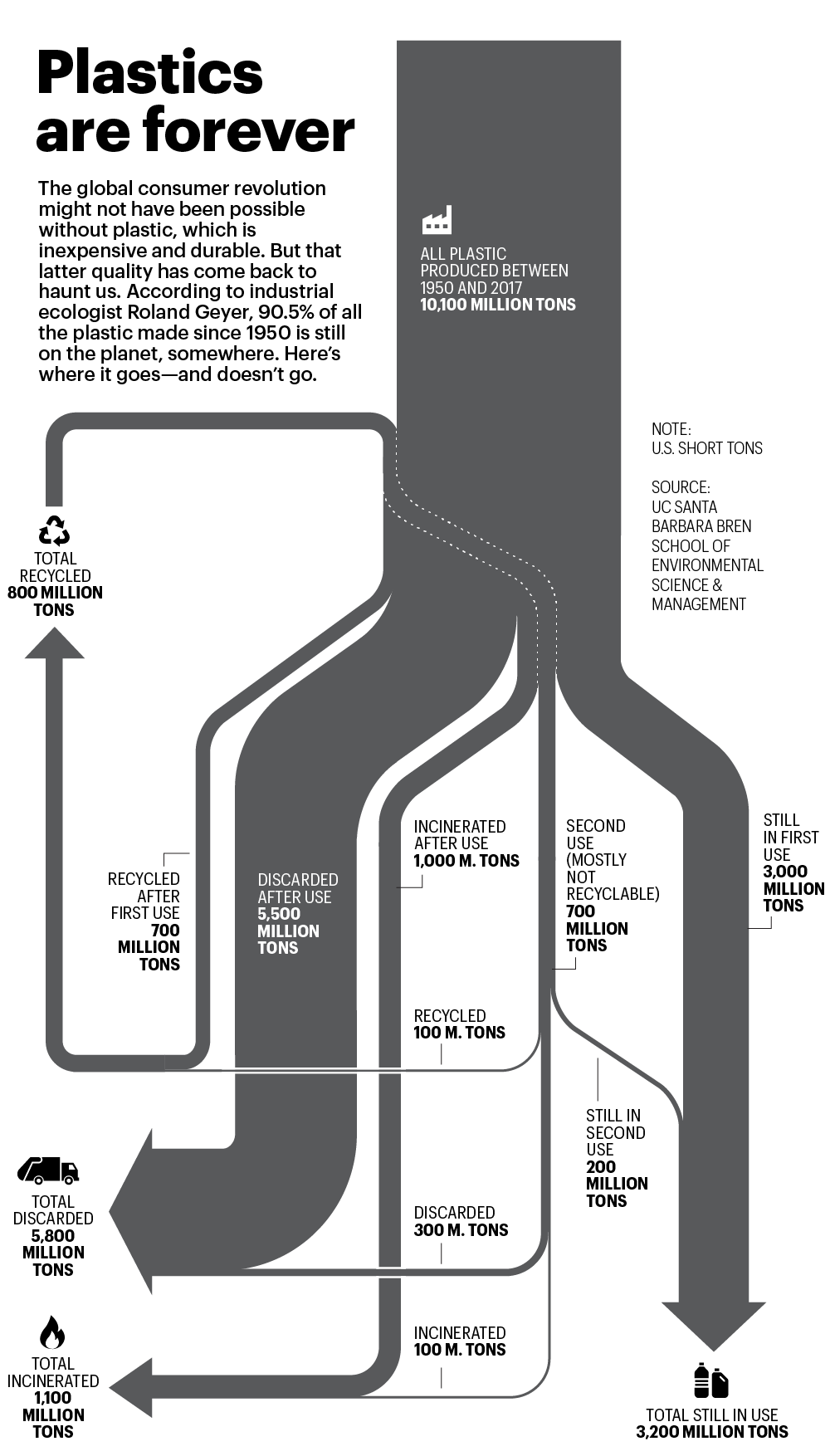

实际情况证明,让塑料如此有吸引力的耐久性同样让塑料成了一枚环境定时炸弹。加州大学圣巴巴拉分校布伦环境科学与管理学院工业生态学教授罗兰德·耶尔估算,1950年生产的所有塑料中,90.5%目前依然存在。美国环境保护署的数据显示,2017年美国只有8.4%的废塑料得到了回收,另有15.8%用于燃烧发电,其他的则都被填埋了起来。在亚洲和非洲的部分地区,塑料的回收利用率甚至更低。就连环保法律严格的欧洲,塑料的回收利用率也只有30%左右。

几十年来,塑料生产商及其主要客户,比如可口可乐、雀巢、百事和宝洁等消费品巨头一直在说,提高回收利用水平是解决塑料废品危机的办法。这些公司认为这是一个行为问题,而且源于我们的行为。美国塑料工业协会的总裁兼首席执行官托尼·拉多斯泽维斯基说:“说问题在于塑料就像是膝跳反射。罪魁祸首是没有正确处置塑料产品的消费者。”

塑料回收率确实很低。但仅将此归咎于消费者也着实不妥。更大的问题在于能源市场的巨大变化。10年来石油和天然气价格直线下滑,从而造成石化公司的新塑料生产成本远低于塑料厂商的可回收塑料。在有大量利润可图的情况下,这些公司的新塑料产量猛增,进一步压低了价格。二手塑料回收是劳动力密集型活动,因此成本很高,而且世界上很大一部分地区目前的经济形势变化也不利于塑料回收。

2018年,中国停止了几乎所有塑料废品的进口,理由是中国自己的资源回收行业正在危害环境,这个生态系统因此再遭重击。此项决定让我们这个世界的塑料复兴经济陷入混乱。举例来说,2018年以前,美国一直将70%左右的废塑料送到中国。而现在,纽约州Smithtown的固体废物协调员麦克·恩格尔曼说:“回收利用行业就像用上了生命维持系统的病人。” Smithtown在长岛郊区,有12万居民。恩格尔曼表示:“希望情况将出现好转。但我不能肯定会怎样好转。”

改善的途径之一是限制新塑料的生产和使用,但考虑到石化和能源行业的政治影响力,这种方法存在很大的不确定性。实际上,繁荣的塑料市场对能源行业的长期健康而言已经变得举足轻重。国际能源机构认为,随着汽车厂商转向电动汽车以及可再生能源的腾飞,塑料将成为石油天然气行业的新增长引擎。该机构估算,石化原料占全球石油总需求的比重将从目前的12%升至2040年的22%,届时石化原料有可能成为油气行业唯一增长的领域,而石化原料中有很大一部分都用于制造塑料。

这样看,大公司在回应消费者顾虑时未强调供给侧就不奇怪了。今年1月,陶氏化学、杜邦、雪佛龙和宝洁等大型企业成立了清除塑料废弃物行动联盟。宝洁的首席执行官戴怀德对记者表示,塑料危机“需要我们所有人立即采取行动”。

但“立即采取行动”并不包括减产。相反,这些公司承诺将在今后五年内为废弃物回收利用项目投入15亿美元。美国化学理事会的董事总经理克里斯特曼以Renew Oceans项目为例,后者的目标是清理印度恒河中的塑料废物。他说上述联盟的目标是到2030年使塑料包装物“100%可回收”,到2040年确保所有塑料包装物都得到回收。但当我问他回收如此之多的塑料产生的巨大成本由谁承担时,他迟疑了一下,然后说:“会有融资措施。部分资金将来自相关行业,部分来自政府。”

环保人士指出,塑料持久的寿命降低了上述说法的可信度。此外,就像耶尔研究显示的那样,大多数已经回收过一次的塑料无法再次回收。换句话说就是,我们给地球添加的几乎所有塑料都很有可能留存下来,而且是和以前的几乎所有塑料一起。

在一个蒸笼般的下午,塑料贸易商史蒂夫·黄坐在马来西亚中部城市怡保的一家路边小餐馆中。他正和一位老客户、当地资源回收公司AZ Plastikar的首席执行官赛基·杨会面。在嗡嗡作响的电扇下,两人吃着辣饺子和卤肉卷,喝着茉莉花茶,谈起生意来。他们用的就是塑料桌子,坐的黄色椅子也是塑料的。

黄拿出几个袋子,把其中装的东西摆在杨面前。其中一个袋子里装的是来自巴黎多家时装店的衣架。另一个袋子里是一卷塑料绳,这是一张聚丙烯渔网剩下的一部分,是黄在荷兰买的。两人弓着身体,在桌上把渔网扯开来查看其中的聚合物,他们还用打火机燎了燎扯下来的绳头,目的是闻闻味道,以便判断它的化学成分。黄对杨说:“看,这很好,我们可以回收这些,这样的有很多,渔民通常只会把它们扔到海里。”

黄是卜高通美有限公司的首席执行官,在塑料行业德高望重, 1984年在香港成立了卜高通美。他看上去就像一位精力充沛的上门推销员,从某种意义上讲,也的确是这样。为了给废塑料中的几百种不同聚合物找到适于加工的工厂,他很大一部分时间都在美国、欧洲和亚洲之间奔波。5美元的午餐加上无数壶茶,重大回收生意就是在这样的场合谈成的,而不是光鲜的董事会会议室(在另一个下午的另一次会面中,一家华人工厂的老板敬了黄很多自酿米酒。在他的妻子为我们准备一大桌中国菜肴的时候,他和黄用不太结实的烤箱测试了塑料样品)。

在怡保,杨同意每个月购买大约600吨聚丙烯,价值22.8万美元左右。但他担心不断贬值的货砸在手里,近来这种情况很普遍。杨说:“生产新塑料比回收便宜太多了。这对我们来说是个大问题。”

在马来西亚各个地方的工厂里,我们都听到了类似的情况。YB Enterprise董事总经理、59岁的叶冠发用手比了一把枪,对着自己的脑袋说:“如果你现在来要我开这家公司,那还不如杀了我。”叶的回收工厂占地10英亩(约40460平方米),位于他的家乡巴东色海的油棕榈树林里。叶从17岁开始在巴东色海做资源回收利用,现在每个月回收约1000吨塑料。但在过去6个月时间里,他的产品价格下降了20%,来自中国的订单也减少了一半。

塑料公司Fizlestari的工厂设在吉隆坡以南的汝来,在那里,装着澳大利亚、美国和英国矿泉水瓶、饮料瓶的大包一直堆到了房顶。这家工厂去年的收入约为1000万美元,但成品销量比2017年,也就是该厂开业的第一年少了25%。首席执行官赛瑟尔·陈告诉我:“价格下跌了非常、非常、非常多,而且我觉得它不会很快回升。”

62岁的黄早就听到过这样的话,也感受到了经济上的影响。他在香港为父亲的小回收作坊收废品时还是个小孩。黄说:“我那时还在上小学,连10岁还不到。”最终,他把小作坊发展成了盈利的企业,并于2000年和夫人以及六个子女移居到了加州Diamond Park。当时他在全球范围内经营着20多家工厂,包括德国、英国、南非和澳大利亚。他说大多数时间里,光是香港的业务每年就能赚1000万美元。和大多数回收商一样,他最大的市场是中国。

这一切都在2018年毁于一旦,中国展开了“国门利剑”行动,禁止进口塑料废弃物。此前很长一段时间里中国一直允许大量进口废塑料。但兴旺的废塑料加工行业却导致了环境污染。如今中国只允许进口几乎不含污染物的废品,而最多也只有1%的废品能达到这一标准。佐治亚大学工程学院预计,今后10年全世界将有约1.11亿吨废塑料需要另寻出路。

中国政府的措施切断了黄的财富来源。他估算,“国门利剑”行动以来,自己的生意萎缩了90%以上,工厂也关的只剩下了5家。现在他的主要赚钱途径是当中间人,把废品介绍给中国大幅调整政策后出现的那几千家回收工厂。有许多回收厂是从中国迁到泰国、越南和马来西亚的,吸引它们的是便宜的土地和甚至更低的劳动力成本,或者说来自孟加拉国、巴基斯坦和缅甸的打工者。

走进黄的客户的工厂才会发现这种工作的劳动力密集度会有多高,以及为什么人们可能不想让这些工厂开在自己家旁边。

在工厂里,工人们梳理塞满集装箱的废塑料。他们把二手塑料分类,挑拣出PET(聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯,广泛用于饮料瓶和包装)和LDPE(低密度聚乙烯,用于制造一次性购物袋)等材料。这些聚合物有几百种,每一种都需要专门的加工方法。分拣完毕后,这些废塑料将在机器中清洗,再加工成纱线那样的细丝。然后把这些细丝放进磨床,磨成米粒大小,成为人们所说的塑料颗粒。回收商再把这些颗粒打包,作为原材料卖给制造商。很大一部分颗粒都送到了中国的工厂,在这里它们会重新进入消费体系的“血液循环”之中,成为汽车零部件、玩具、矿泉水瓶,以及数千种其他产品的原料。

这个过程很了不起,但它的效率绝不是100%。许多厂商想要回收的聚合物都达不到制造业需要的等级。污损的塑料通常都无法重新利用。同时,大量涌现的新塑料带来的价格压力只会让情况变得更糟。澳大利亚公司ResourceCo Asia驻怡保的运营主管穆拉林德兰·科温达萨米说:“目前回收这些没有经济价值。”他买下了一些马来西亚工厂无法使用的塑料,然后把这些塑料卖给了水泥公司,作为铺设道路的材料。其他大多数回收厂只会烧掉或掩埋这些塑料。他指出:“执行情况很不好,把它们扔到填埋场里比较省钱。”

当我问她马来西亚的废塑料贸易增长的有多快时,时任马来西亚环境部长杨美盈看起来很苦恼。在布城联邦政府行政中心的顶层办公室里,杨美盈估算此项贸易每年对经济的贡献只有10亿美元,而且她认为正在全力以赴地对付废塑料回收企业。后者需要拿到19张环保许可证才能开工。同时,仅去年杨美盈就关闭了200多家回收厂,原因是证照不全。她说,如果需要,马来西亚政府应该“断电、断水,切断所有可以切断的东西。他们就像一帮土匪。”

杨美盈发起的战斗正在等待新的将领——接受我采访几周后,她和马来西亚政府其他成员在议会危机中全体辞职。但无论谁接替她,都会有健康专家和普通民众作为同盟,而且原因再明显不过了。

我们在马来西亚的第一个上午,塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶和我爬上了双溪大年中心一座约15米高的塑料山。这座小城在槟城附近,有大约20万居民。废品山由附近各家工厂认为不能回收的塑料堆积而成。这是塑料供应链的最末端。接下来唯一的办法似乎就是把它烧掉,而且有些人就是这么做的。双溪大年Metro医院负责人、内科医生Tneoh Shen Jen说工厂反复非法燃烧废塑料已经使当地居民出现了呼吸问题。他表示:他们“在大多数晚上都闻到了烧塑料的味道”。

在附近的社区中,40岁的Tei Jean和她六岁的女儿坐在家中。她们的窗户是封死的,家里也没有玩具、毯子和窗帘。为了防止女儿的呼吸系统感染,Tei竭尽了全力。她说,去年她们家附近的塑料回收厂开工后不久,女儿就患上了呼吸系统疾病。从那时起,这位小女孩已经三次住院,去年在家待了六个月,没有去上学。Tei说:“她的情况一直在恶化。每次出门她的眼睛就会发红。”现在,她的女儿就待在安静、昏暗的客厅里,靠在粉红色小桌子上画画来打发时光。

双溪大年的活动人士进行抗议后,工厂主从去年秋天开始不再焚烧塑料。但双方仍相互敌视。去年4月有人趁着夜晚在两家回收厂纵火。工厂主说这是环保组织所为。我们去看那座垃圾山时,一位保安用手机拍下了我们的照片,然后发给马来西亚所有的回收厂,让他们警惕我们的到来。几天后,工厂主用怀疑的眼光看着我们,问道:“你们是跟那些环保主义者一起的吗?”

有一次我们是在一起。一天,在双溪大年附近,两位活动人士带着我们沿着慕达河旁的土路走了一遭。这条河是当地农场的水源。在那里,离一所幼儿园不远就有一座巨大的无证废品堆。桔黄色的水塘散发出难闻的化学品气味,其中充斥着西方消费者一眼就能认出来的塑料物品——汰渍洗衣液瓶子、Poland Spring矿泉水瓶、Green Giant冷冻豆子包装袋。当地人说回收工厂把不想要的东西都堆在了这里,这是违反马来西亚法律的。一位自卸卡车司机看到我们后就赶紧离开了(两天后,这堆废弃物被烧掉了,在当地报纸刊登的照片上能看到树丛后冒出的黑色浓烟)。

马来西亚人希望在针对危险废物的巴塞尔公约帮助下让自己免受这样的不良影响,该公约将于明年1月生效,它禁止运输任何有毒的塑料废品,而且已经得到世界上几乎所有国家签字认可,但美国除外。

马来西亚官员已经开始阻拦他们怀疑违反规定的集装箱。在一个狂风大作的周日下午,海关官员带我们巡视了槟城的集装箱码头,向我们展示了做好标记,将遣返美国、法国和英国的集装箱船,而且成本由运输方承担。不过,这些遣返行动很快就会在官僚主义迷宫里泥足深陷。一艘来自奥克兰的集装箱船被打上了遣返标记,但它从2018年6月就一直停靠在槟城的集装箱码头。

前环境部长杨美盈相信,严格执行巴塞尔公约前应当限制废塑料进口,而且不光是马来西亚,菲律宾和印尼等周边资源回收枢纽也应如此。人们对废塑料贸易越发不满。她问我:“我们国家为什么要成为你们的垃圾场?因为这样对你们来说更方便吗?这不公平!”

实际上,几乎没有人哪怕短暂地思考一下他们的垃圾去往何方。大多数人都假设当他们把垃圾桶推到路边后,一个运转良好的回收系统就会接手。

1月的一个凌晨,我们追踪了Smithtown的垃圾车,后者证明了上述假设错的有多离谱。2020年的第一个回收日,这些卡车在一个垃圾中转站卸下了103吨塑料,而这个中转站曾经是一个功能齐全的资源回收点。2014年,Smithtown通过向迫不及待的回收公司出售废品赚了87.8万美元。现在,他们每年要向垃圾处理公司支付近8万美元才能将垃圾脱手。

Smithtown的困难是美国整体情况的典型体现,而且这些困难在中国发布禁令前就出现了。随着石油和天然气价格暴跌,消纳Smithtown二手塑料的市场消失了,而且新塑料就是比前者更便宜。因此,这个Smithtown大幅削减了回收规模,目前只接受质量较高的聚合物,也就是“1类”和“2类”,这是三角形回收标志中的数字。等级较低的塑料,即“3类”到“7类”,再也卖不出去了。在美国,数百个小镇都做出了类似的决定,而且有几十个小镇干脆彻底终止了路边回收。

现在,卡车公司会把在Smithtown收的废塑料送到布鲁克林的Sims市政回收中心。由于Smithtown所在的长岛禁止填埋固体废物,许多低等级塑料最终都在亨廷顿附近的一家垃圾焚烧发电厂烧掉了。Smithtown卫生监督员尼尔·席安说,真正的塑料回收几乎已经不可能了:“把它送到世界上其他地方的成本仍然较低,然后它会以其他形式回到这里。”

如果目前的趋势继续下去,这种局面就不大可能出现改变。油气公司正在为今后新塑料的繁荣投入大量资金。跨国巨头壳牌正在匹兹堡附近修建大型综合设施,而匹兹堡是美国的油气压裂开采中心之一。该综合设施每年将生产大约35亿磅(约157.5万吨)聚乙烯塑料(宾夕法尼亚州议会已决定为该厂减税25年,估算减税额16亿美元)。今年1月,台塑集团获准在路易斯安那州修建价值94亿美元的综合设施,该集团称该设施将创造1200个就业机会。

这些工厂本身就存在环境问题。游说组织国际环境法中心指出,石化行业的扩张可能给“地区气候带来巨大而且不断增长的威胁”。该组织预计,到2050年生产塑料排放的温室气体将相当于大约615个新建燃煤发电厂的排放量。加州大学圣巴巴拉分校的耶尔教授估算,到那时全世界的新塑料年产量将超过11亿吨。

像双溪大年这样的垃圾堆已经激怒了周边居民和监管部门。图片来源:PHOTOGRAPH BY SEBASTIAN MEYER

像双溪大年这样的垃圾堆已经激怒了周边居民和监管部门。图片来源:PHOTOGRAPH BY SEBASTIAN MEYER耶尔说经过多年来对行业数据的研究,他得出了一个结论:“最困难的是阻止新塑料生产规模的继续上升,但我们必须去做。”

塑料生产商阻挠此事的能力就像不可消灭的塑料废品一样强,特别是在美国。典型事例就是对塑料袋和其他“一次性”塑料颁布的禁令。从2021年开始,欧盟27国将严格限制一次性塑料,中国各主要城市也将禁止使用塑料袋。在美国,石化公司基本上已经让这样的提议搁浅,只有八个州对一次性塑料下了禁令。在国家层面,两位民主党参议员在2月提出的措施会让企业分担回收成本并暂缓新塑料的增长。但美国塑料工业协会的首席执行官拉多斯泽维斯基说第二项措施“没有成功的希望”。

拉多斯泽维斯基指出,塑料禁令只是政客发出的“高尚信号”,而且玻璃、金属和纸张在使用寿命中制造的污染更大。该协会的游说成员坚持不懈地向议员们传递类似的信息。协会在3月25日召开全国大会的通知中告诉成员单位:“不要让否定者主导塑料的故事。把我们已经知道的告诉国会山上的那些人,那就是塑料有助于改善人们的生活。”

尽管言辞激烈,但有迹象表明部分企业正在重新考虑塑料问题,部分原因是来自消费者施加的压力。

一些服装公司已经证明,回收塑料可以产生奢侈品溢价。2017年,阿迪达斯开始销售用马尔代夫海域中捞起的废塑料制造的高端运动鞋。这款标价200美元的运动鞋一直供不应求,而且去年阿迪达斯生产了1100万双这样的产品。该公司表明目前它计划将新塑料彻底从生产活动中剔除。耐克也已经在设计以回收聚酯纤维为原料的运动服,并计划推广此项措施。

包装食品领域的行为变化甚至有可能带来更大的影响。联合利华的首席执行官艾伦·乔普于去年10月表示,该公司将“从根本上重新考虑”自家产品的包装,并在2025年之前将新塑料使用量降低一半。联合利华的年塑料消耗量已经超过70万吨。

回收利用方面的进步也让人看到了希望。联合利华已经和沙特阿美旗下的SABIC合作,旨在创造使用化学回收方法的包装。他们表示,这个过程将二手塑料分解转化后生成的材料和新塑料一样好。去年,IBM称它已经创造出吞噬PET并将其变为塑料颗粒的化学工艺,和我们在马来西亚的收厂里看到的艰辛清洗和分拣工作相比,此项工艺的效率和可扩展性要高得多。

马来西亚一些回收厂的所有者在这些举措中看到了曙光,或者说他们的塑料颗粒再次成为受青睐商品的一丝希望。台湾资源回收公司Grey Matter Industries的运营长吴度泓说:“耐克和阿迪达斯想告诉消费者他们关心地球,而且将使用100%回收的塑料。”他指出,最近的这些公告或许预示着转折点的到来,“我们也想参与其中”。

在BioGreen Frontier,56岁的公司主管黄永文说他也希望跨国公司行为的改变能帮他拿下大生意。但同时,他对短期问题感到担心。黄永文仍在等待政府给他的工厂颁发批文,也面临着工厂关闭的风险。1月底,和很大一部分全球经济一样,BioGreen Frontier等回收公司受到了新冠疫情的沉重打击。中国在几周内关闭了工厂和港口,并且取消了回收塑料颗粒订单,这给回收公司带来了巨大的困难。2月中旬,黄永文在电话里告诉我,他已经开始在仓库里堆放塑料颗粒了,同时正在寻找新的客户。他说:“我不想把工人赶回家。”

这些工人来自世界上一些最贫穷的国家,他们继续涌进马来西亚,急于回收那些来自世界上一些最富裕国家的废品。对他们来说,尽管废塑料行业陷入了困境,但仍是收入阶梯上的一大进步。“我已经在这里工作两个月了。”站在BioGreen Frontier生产线上的Aung Aung有 25岁,来自缅甸仰光。他说塑料回收的工资远高于此前他在槟城餐馆的工作,“我得考虑我的家庭。”

与此同时,沙希德·阿里制定了远大的计划。他说自己会在BioGreen Frontier再工作两年,然后返还白沙瓦。“接下来我就会结婚。”他站在湿漉漉的、经过清洗的塑料中说,“我有一个心仪的女孩。”在那之前,他愿意每星期在回收线上工作84个小时——可以这样说,他正在废塑料上构建自己的家庭。

抵制塑料

我们对塑料的需求几乎没有止境,而地球消化塑料的能力有限。全世界只有9%的二手塑料得到回收,而每年倾倒进海洋的塑料约有800万吨。废塑料引发的公众愤慨日益高涨,从而推动企业采取大胆措施来解决这个问题。以下三种方法正越来越受欢迎。

1. 化学回收

塑料行业很看好这项解决全球塑料泛滥的策略。这种方法将通常要填埋或焚烧的塑料分解成最初的化学成分,这包括塑料包装袋、薄膜和咖啡胶囊。然后将这些化学成分和新树脂混合,从而做出跟新塑料一样坚固的材料。但它存在下行风险,比如说,这个过程会产生大量的碳,从而限制了它对气候的整体贡献。

2. 生物塑料

和石油原料制造的传统塑料不同,生物塑料的制造方法是从玉米或甘蔗中提炼出糖,然后将其转化为聚乳酸或聚羟基脂肪酸酯。这些材料的外观和触感非常像碳基塑料,但不消耗石化燃料。批评人士认为,用于制作生物材料的农作物需要喷洒杀虫剂,而且会占用本可种植粮食作物的土地。同时,回收生物塑料需要堆肥厂中的高热量,从而增加了二手生物塑料物品被填埋的风险。

3. 按包装付费

应对回收市场瘫痪的措施之一是要求企业向市政府付费,以便回收他们的塑料包装。大多数欧盟国家和一些亚洲国家已经制定了这样的法律。在美国,缅因州议会正在考虑类似的提案。塑料制造商表示他们更愿意提高回收率,而不是分担回收成本。但在欧洲,这样的法律已经开始促使企业减少包装并重新考虑对塑料的使用。(财富中文网)

Selvanaban Mariappen和塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶也为本篇报道做出了贡献

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年4月刊,标题为《恶性循环》。

译者: MS

本文是《财富》杂志《特别报道:面临环境危机的商业》组文之一,与普利策危机报道中心合作发表。摄影:塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶

在马来西亚北部的一处山坡上,一座大型露天厂房矗立在油棕榈树和橡胶树之间。这是生物降解公司BioGreen Frontier设在Bukit Selambau村的再生资源回收工厂,去年11月投产。1月一个骄阳火辣的下午,沙希德·阿里刚刚开始了第一周的工作。他分开双脚,站在生产线尽头向下倾斜的传送带旁,脚边的白色湿软塑料丝深及膝盖。在他周围,更多的细丝从传送带上落下,像雪片一样飘散到地面上。

回收过程中,阿里一直在这堆塑料细丝中挑拣着看起来褪色或者脏了的不合格品。虽然这看起来很累,但阿里说这已经比他上一份工作好多了。此前他在附近的一家纺织厂叠床单,工资也比现在低得多。如今,如果吃的节省一点儿,就能存下钱来。他的时薪略高于1美元,每个月可以向父母和六个兄弟姐妹寄250美元,他们住在4300多公里外的巴基斯坦白沙瓦。24岁的阿里,身材矮胖,留着络腮胡子,戴着眼镜,脸上露出轻松的微笑。他说:“我听说这里招工,就赶紧跑来应聘了。”不过,他每天要工作12个小时,每周工作七天。“如果我休息一天,就会少一天的工资。” 阿里说。

在这座厂房中有几百个大包,堆了差不多有18米高,每个包里都塞满了几周前人们丢弃的塑料外包装和塑料袋。上面的地址标签清楚地指明了它们的来源地。可以看到加州半月湾一个家庭丢弃的厕纸外包装,在埃尔帕索打包。还可以看到聚合物薄膜,来自功能饮料厂商红牛设在圣莫妮卡的总部。

阿里所在的这类工厂是这些废弃物最终的归宿,它们飘洋过海,来到1.2万公里外这个遥远的角落,这首先说明全球资源回收经济和人类对塑料依赖之间存在的巨大差距。这个生态系统严重失灵,甚至已经濒临崩溃。全世界每年都会生产不计其数的塑料,其中约90%最终都没有得到回收利用,而是被烧掉、埋掉或者扔掉了。

而支持塑料回收利用的消费者越来越多,在数以百万计的家庭里,把酸奶盒、果汁瓶放进蓝色垃圾桶已经成了体现环保信仰的行为。但这种信仰也就到此为止。塑料物品每年都如同潮水般涌进回收行业,而且它们越来越有可能原封不动地被退出来,成为一个瘫痪市场的“受害者”。由于经济性太差,消费者眼中(而且业界宣称)的许多“可回收”产品实际上并非如此。随着石油和天然气价格接近20年来的最低点(这在很大程度上要归功于压裂开采技术革命),出现了所谓的新塑料,也就是一种源于石油原料的产品,其售价和获取难度要远低于可回收材料。对于直到现在仍只是勉强生存的资源回收行业来说,这种无法预见的变化无异于毁灭性的打击。绿色和平组织的全球塑料行动负责人格拉汉姆·福布斯说:“全球废品贸易实际上已经中断。我们坐拥大堆塑料,却无处可送,也无法处理。”

对于如此巨大的超负荷所引发的矛盾,业界和政府再也不能视而不见。这个矛盾源于塑料的盈利能力和用处及其对公众健康和环境的威胁,而且几乎没有什么地方能比马来西亚更能体现这种矛盾。在这里,超低的工资、便宜的土地以及仍在形成的监管气候吸引企业主建立了几百家回收工厂,这是他们为保持盈利的最后一搏。我和摄影师塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶走过了马来西亚各地,清楚地看到了回收利用塑料的实际经济和环境成本。我们在10天时间里走访了10家回收工厂,其中一些,包括BioGreen Frontier的运营都没有官方备案,所以有停工风险,而他们处理的是一船船来自世界各地的废品。我们还看到了塑料经济崩溃后对垃圾场、集装箱码头、家庭以及广阔海洋的影响。

过去50年塑料的发展呈直线上升态势,理由很充分,那就是它们便宜、轻便而且基本上不会损坏。在1967年的电影《毕业生》(The Graduate)中,后来的导师对紧张兮兮的年轻人本杰明·布拉多克(达斯汀·霍夫曼饰)说:“塑料非常有前途。”基于这样的提点来采取行动有可能产生巨大收益。塑料的全球年产量从1970年的2500万吨飙升至2018年的4亿吨以上。

塑料泛滥的背后是巨大的经济利益——英国数据分析机构Business Research Co.指出,去年全球塑料市场的价值约为1万亿美元。2000年以来塑料需求已经翻了一番,而且到2050年可能再增长一倍。塑料行业组织美国化学理事会的成员包括陶氏化学、杜邦、雪佛龙和埃克森美孚等主要厂商。该组织负责塑料市场的董事总经理基思·克里斯特曼说:“在世界各地,需要提高生活质量的中产阶层正在不断增多。塑料已然成为人们生活的一部分。”大家可以看到,不光是矿泉水瓶和三明治包装袋用塑料,其他含有塑料的东西不胜枚举,比如运动衫、湿纸巾、建筑隔音材料和墙板、口香糖和茶包。

关于碳排放的争论往往会掩盖人们对塑料的担心。但这两个问题紧密相连,因为塑料生产本身就会排放数量可观的温室气体。现在世界已经充分认识到了塑料危机。海龟被塑料吸管噎住,死去鲸鱼肚子里塞满塑料垃圾的图片早已广为流传——它们的背后是每年流入海洋的800万吨塑料(联合国环境规划署估算,到2050年海洋中的塑料数量将超过鱼类)。人类不可避免的会受到影响。世界自然基金会资助的研究显示,每位美国人平均每星期通过食物至少会吃下去一茶匙的塑料,差不多相当于一张信用卡,由此产生的健康问题还无法预测。

实际情况证明,让塑料如此有吸引力的耐久性同样让塑料成了一枚环境定时炸弹。加州大学圣巴巴拉分校布伦环境科学与管理学院工业生态学教授罗兰德·耶尔估算,1950年生产的所有塑料中,90.5%目前依然存在。美国环境保护署的数据显示,2017年美国只有8.4%的废塑料得到了回收,另有15.8%用于燃烧发电,其他的则都被填埋了起来。在亚洲和非洲的部分地区,塑料的回收利用率甚至更低。就连环保法律严格的欧洲,塑料的回收利用率也只有30%左右。

几十年来,塑料生产商及其主要客户,比如可口可乐、雀巢、百事和宝洁等消费品巨头一直在说,提高回收利用水平是解决塑料废品危机的办法。这些公司认为这是一个行为问题,而且源于我们的行为。美国塑料工业协会的总裁兼首席执行官托尼·拉多斯泽维斯基说:“说问题在于塑料就像是膝跳反射。罪魁祸首是没有正确处置塑料产品的消费者。”

塑料回收率确实很低。但仅将此归咎于消费者也着实不妥。更大的问题在于能源市场的巨大变化。10年来石油和天然气价格直线下滑,从而造成石化公司的新塑料生产成本远低于塑料厂商的可回收塑料。在有大量利润可图的情况下,这些公司的新塑料产量猛增,进一步压低了价格。二手塑料回收是劳动力密集型活动,因此成本很高,而且世界上很大一部分地区目前的经济形势变化也不利于塑料回收。

2018年,中国停止了几乎所有塑料废品的进口,理由是中国自己的资源回收行业正在危害环境,这个生态系统因此再遭重击。此项决定让我们这个世界的塑料复兴经济陷入混乱。举例来说,2018年以前,美国一直将70%左右的废塑料送到中国。而现在,纽约州Smithtown的固体废物协调员麦克·恩格尔曼说:“回收利用行业就像用上了生命维持系统的病人。” Smithtown在长岛郊区,有12万居民。恩格尔曼表示:“希望情况将出现好转。但我不能肯定会怎样好转。”

改善的途径之一是限制新塑料的生产和使用,但考虑到石化和能源行业的政治影响力,这种方法存在很大的不确定性。实际上,繁荣的塑料市场对能源行业的长期健康而言已经变得举足轻重。国际能源机构认为,随着汽车厂商转向电动汽车以及可再生能源的腾飞,塑料将成为石油天然气行业的新增长引擎。该机构估算,石化原料占全球石油总需求的比重将从目前的12%升至2040年的22%,届时石化原料有可能成为油气行业唯一增长的领域,而石化原料中有很大一部分都用于制造塑料。

这样看,大公司在回应消费者顾虑时未强调供给侧就不奇怪了。今年1月,陶氏化学、杜邦、雪佛龙和宝洁等大型企业成立了清除塑料废弃物行动联盟。宝洁的首席执行官戴怀德对记者表示,塑料危机“需要我们所有人立即采取行动”。

但“立即采取行动”并不包括减产。相反,这些公司承诺将在今后五年内为废弃物回收利用项目投入15亿美元。美国化学理事会的董事总经理克里斯特曼以Renew Oceans项目为例,后者的目标是清理印度恒河中的塑料废物。他说上述联盟的目标是到2030年使塑料包装物“100%可回收”,到2040年确保所有塑料包装物都得到回收。但当我问他回收如此之多的塑料产生的巨大成本由谁承担时,他迟疑了一下,然后说:“会有融资措施。部分资金将来自相关行业,部分来自政府。”

环保人士指出,塑料持久的寿命降低了上述说法的可信度。此外,就像耶尔研究显示的那样,大多数已经回收过一次的塑料无法再次回收。换句话说就是,我们给地球添加的几乎所有塑料都很有可能留存下来,而且是和以前的几乎所有塑料一起。

在一个蒸笼般的下午,塑料贸易商史蒂夫·黄坐在马来西亚中部城市怡保的一家路边小餐馆中。他正和一位老客户、当地资源回收公司AZ Plastikar的首席执行官赛基·杨会面。在嗡嗡作响的电扇下,两人吃着辣饺子和卤肉卷,喝着茉莉花茶,谈起生意来。他们用的就是塑料桌子,坐的黄色椅子也是塑料的。

黄拿出几个袋子,把其中装的东西摆在杨面前。其中一个袋子里装的是来自巴黎多家时装店的衣架。另一个袋子里是一卷塑料绳,这是一张聚丙烯渔网剩下的一部分,是黄在荷兰买的。两人弓着身体,在桌上把渔网扯开来查看其中的聚合物,他们还用打火机燎了燎扯下来的绳头,目的是闻闻味道,以便判断它的化学成分。黄对杨说:“看,这很好,我们可以回收这些,这样的有很多,渔民通常只会把它们扔到海里。”

黄是卜高通美有限公司的首席执行官,在塑料行业德高望重, 1984年在香港成立了卜高通美。他看上去就像一位精力充沛的上门推销员,从某种意义上讲,也的确是这样。为了给废塑料中的几百种不同聚合物找到适于加工的工厂,他很大一部分时间都在美国、欧洲和亚洲之间奔波。5美元的午餐加上无数壶茶,重大回收生意就是在这样的场合谈成的,而不是光鲜的董事会会议室(在另一个下午的另一次会面中,一家华人工厂的老板敬了黄很多自酿米酒。在他的妻子为我们准备一大桌中国菜肴的时候,他和黄用不太结实的烤箱测试了塑料样品)。

在怡保,杨同意每个月购买大约600吨聚丙烯,价值22.8万美元左右。但他担心不断贬值的货砸在手里,近来这种情况很普遍。杨说:“生产新塑料比回收便宜太多了。这对我们来说是个大问题。”

在马来西亚各个地方的工厂里,我们都听到了类似的情况。YB Enterprise董事总经理、59岁的叶冠发用手比了一把枪,对着自己的脑袋说:“如果你现在来要我开这家公司,那还不如杀了我。”叶的回收工厂占地10英亩(约40460平方米),位于他的家乡巴东色海的油棕榈树林里。叶从17岁开始在巴东色海做资源回收利用,现在每个月回收约1000吨塑料。但在过去6个月时间里,他的产品价格下降了20%,来自中国的订单也减少了一半。

塑料公司Fizlestari的工厂设在吉隆坡以南的汝来,在那里,装着澳大利亚、美国和英国矿泉水瓶、饮料瓶的大包一直堆到了房顶。这家工厂去年的收入约为1000万美元,但成品销量比2017年,也就是该厂开业的第一年少了25%。首席执行官赛瑟尔·陈告诉我:“价格下跌了非常、非常、非常多,而且我觉得它不会很快回升。”

62岁的黄早就听到过这样的话,也感受到了经济上的影响。他在香港为父亲的小回收作坊收废品时还是个小孩。黄说:“我那时还在上小学,连10岁还不到。”最终,他把小作坊发展成了盈利的企业,并于2000年和夫人以及六个子女移居到了加州Diamond Park。当时他在全球范围内经营着20多家工厂,包括德国、英国、南非和澳大利亚。他说大多数时间里,光是香港的业务每年就能赚1000万美元。和大多数回收商一样,他最大的市场是中国。

这一切都在2018年毁于一旦,中国展开了“国门利剑”行动,禁止进口塑料废弃物。此前很长一段时间里中国一直允许大量进口废塑料。但兴旺的废塑料加工行业却导致了环境污染。如今中国只允许进口几乎不含污染物的废品,而最多也只有1%的废品能达到这一标准。佐治亚大学工程学院预计,今后10年全世界将有约1.11亿吨废塑料需要另寻出路。

中国政府的措施切断了黄的财富来源。他估算,“国门利剑”行动以来,自己的生意萎缩了90%以上,工厂也关的只剩下了5家。现在他的主要赚钱途径是当中间人,把废品介绍给中国大幅调整政策后出现的那几千家回收工厂。有许多回收厂是从中国迁到泰国、越南和马来西亚的,吸引它们的是便宜的土地和甚至更低的劳动力成本,或者说来自孟加拉国、巴基斯坦和缅甸的打工者。

走进黄的客户的工厂才会发现这种工作的劳动力密集度会有多高,以及为什么人们可能不想让这些工厂开在自己家旁边。

在工厂里,工人们梳理塞满集装箱的废塑料。他们把二手塑料分类,挑拣出PET(聚对苯二甲酸乙二醇酯,广泛用于饮料瓶和包装)和LDPE(低密度聚乙烯,用于制造一次性购物袋)等材料。这些聚合物有几百种,每一种都需要专门的加工方法。分拣完毕后,这些废塑料将在机器中清洗,再加工成纱线那样的细丝。然后把这些细丝放进磨床,磨成米粒大小,成为人们所说的塑料颗粒。回收商再把这些颗粒打包,作为原材料卖给制造商。很大一部分颗粒都送到了中国的工厂,在这里它们会重新进入消费体系的“血液循环”之中,成为汽车零部件、玩具、矿泉水瓶,以及数千种其他产品的原料。

这个过程很了不起,但它的效率绝不是100%。许多厂商想要回收的聚合物都达不到制造业需要的等级。污损的塑料通常都无法重新利用。同时,大量涌现的新塑料带来的价格压力只会让情况变得更糟。澳大利亚公司ResourceCo Asia驻怡保的运营主管穆拉林德兰·科温达萨米说:“目前回收这些没有经济价值。”他买下了一些马来西亚工厂无法使用的塑料,然后把这些塑料卖给了水泥公司,作为铺设道路的材料。其他大多数回收厂只会烧掉或掩埋这些塑料。他指出:“执行情况很不好,把它们扔到填埋场里比较省钱。”

当我问她马来西亚的废塑料贸易增长的有多快时,时任马来西亚环境部长杨美盈看起来很苦恼。在布城联邦政府行政中心的顶层办公室里,杨美盈估算此项贸易每年对经济的贡献只有10亿美元,而且她认为正在全力以赴地对付废塑料回收企业。后者需要拿到19张环保许可证才能开工。同时,仅去年杨美盈就关闭了200多家回收厂,原因是证照不全。她说,如果需要,马来西亚政府应该“断电、断水,切断所有可以切断的东西。他们就像一帮土匪。”

杨美盈发起的战斗正在等待新的将领——接受我采访几周后,她和马来西亚政府其他成员在议会危机中全体辞职。但无论谁接替她,都会有健康专家和普通民众作为同盟,而且原因再明显不过了。

我们在马来西亚的第一个上午,塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶和我爬上了双溪大年中心一座约15米高的塑料山。这座小城在槟城附近,有大约20万居民。废品山由附近各家工厂认为不能回收的塑料堆积而成。这是塑料供应链的最末端。接下来唯一的办法似乎就是把它烧掉,而且有些人就是这么做的。双溪大年Metro医院负责人、内科医生Tneoh Shen Jen说工厂反复非法燃烧废塑料已经使当地居民出现了呼吸问题。他表示:他们“在大多数晚上都闻到了烧塑料的味道”。

在附近的社区中,40岁的Tei Jean和她六岁的女儿坐在家中。她们的窗户是封死的,家里也没有玩具、毯子和窗帘。为了防止女儿的呼吸系统感染,Tei竭尽了全力。她说,去年她们家附近的塑料回收厂开工后不久,女儿就患上了呼吸系统疾病。从那时起,这位小女孩已经三次住院,去年在家待了六个月,没有去上学。Tei说:“她的情况一直在恶化。每次出门她的眼睛就会发红。”现在,她的女儿就待在安静、昏暗的客厅里,靠在粉红色小桌子上画画来打发时光。

双溪大年的活动人士进行抗议后,工厂主从去年秋天开始不再焚烧塑料。但双方仍相互敌视。去年4月有人趁着夜晚在两家回收厂纵火。工厂主说这是环保组织所为。我们去看那座垃圾山时,一位保安用手机拍下了我们的照片,然后发给马来西亚所有的回收厂,让他们警惕我们的到来。几天后,工厂主用怀疑的眼光看着我们,问道:“你们是跟那些环保主义者一起的吗?”

有一次我们是在一起。一天,在双溪大年附近,两位活动人士带着我们沿着慕达河旁的土路走了一遭。这条河是当地农场的水源。在那里,离一所幼儿园不远就有一座巨大的无证废品堆。桔黄色的水塘散发出难闻的化学品气味,其中充斥着西方消费者一眼就能认出来的塑料物品——汰渍洗衣液瓶子、Poland Spring矿泉水瓶、Green Giant冷冻豆子包装袋。当地人说回收工厂把不想要的东西都堆在了这里,这是违反马来西亚法律的。一位自卸卡车司机看到我们后就赶紧离开了(两天后,这堆废弃物被烧掉了,在当地报纸刊登的照片上能看到树丛后冒出的黑色浓烟)。

马来西亚人希望在针对危险废物的巴塞尔公约帮助下让自己免受这样的不良影响,该公约将于明年1月生效,它禁止运输任何有毒的塑料废品,而且已经得到世界上几乎所有国家签字认可,但美国除外。

马来西亚官员已经开始阻拦他们怀疑违反规定的集装箱。在一个狂风大作的周日下午,海关官员带我们巡视了槟城的集装箱码头,向我们展示了做好标记,将遣返美国、法国和英国的集装箱船,而且成本由运输方承担。不过,这些遣返行动很快就会在官僚主义迷宫里泥足深陷。一艘来自奥克兰的集装箱船被打上了遣返标记,但它从2018年6月就一直停靠在槟城的集装箱码头。

前环境部长杨美盈相信,严格执行巴塞尔公约前应当限制废塑料进口,而且不光是马来西亚,菲律宾和印尼等周边资源回收枢纽也应如此。人们对废塑料贸易越发不满。她问我:“我们国家为什么要成为你们的垃圾场?因为这样对你们来说更方便吗?这不公平!”

实际上,几乎没有人哪怕短暂地思考一下他们的垃圾去往何方。大多数人都假设当他们把垃圾桶推到路边后,一个运转良好的回收系统就会接手。

1月的一个凌晨,我们追踪了Smithtown的垃圾车,后者证明了上述假设错的有多离谱。2020年的第一个回收日,这些卡车在一个垃圾中转站卸下了103吨塑料,而这个中转站曾经是一个功能齐全的资源回收点。2014年,Smithtown通过向迫不及待的回收公司出售废品赚了87.8万美元。现在,他们每年要向垃圾处理公司支付近8万美元才能将垃圾脱手。

Smithtown的困难是美国整体情况的典型体现,而且这些困难在中国发布禁令前就出现了。随着石油和天然气价格暴跌,消纳Smithtown二手塑料的市场消失了,而且新塑料就是比前者更便宜。因此,这个Smithtown大幅削减了回收规模,目前只接受质量较高的聚合物,也就是“1类”和“2类”,这是三角形回收标志中的数字。等级较低的塑料,即“3类”到“7类”,再也卖不出去了。在美国,数百个小镇都做出了类似的决定,而且有几十个小镇干脆彻底终止了路边回收。

现在,卡车公司会把在Smithtown收的废塑料送到布鲁克林的Sims市政回收中心。由于Smithtown所在的长岛禁止填埋固体废物,许多低等级塑料最终都在亨廷顿附近的一家垃圾焚烧发电厂烧掉了。Smithtown卫生监督员尼尔·席安说,真正的塑料回收几乎已经不可能了:“把它送到世界上其他地方的成本仍然较低,然后它会以其他形式回到这里。”

如果目前的趋势继续下去,这种局面就不大可能出现改变。油气公司正在为今后新塑料的繁荣投入大量资金。跨国巨头壳牌正在匹兹堡附近修建大型综合设施,而匹兹堡是美国的油气压裂开采中心之一。该综合设施每年将生产大约35亿磅(约157.5万吨)聚乙烯塑料(宾夕法尼亚州议会已决定为该厂减税25年,估算减税额16亿美元)。今年1月,台塑集团获准在路易斯安那州修建价值94亿美元的综合设施,该集团称该设施将创造1200个就业机会。

这些工厂本身就存在环境问题。游说组织国际环境法中心指出,石化行业的扩张可能给“地区气候带来巨大而且不断增长的威胁”。该组织预计,到2050年生产塑料排放的温室气体将相当于大约615个新建燃煤发电厂的排放量。加州大学圣巴巴拉分校的耶尔教授估算,到那时全世界的新塑料年产量将超过11亿吨。

耶尔说经过多年来对行业数据的研究,他得出了一个结论:“最困难的是阻止新塑料生产规模的继续上升,但我们必须去做。”

塑料生产商阻挠此事的能力就像不可消灭的塑料废品一样强,特别是在美国。典型事例就是对塑料袋和其他“一次性”塑料颁布的禁令。从2021年开始,欧盟27国将严格限制一次性塑料,中国各主要城市也将禁止使用塑料袋。在美国,石化公司基本上已经让这样的提议搁浅,只有八个州对一次性塑料下了禁令。在国家层面,两位民主党参议员在2月提出的措施会让企业分担回收成本并暂缓新塑料的增长。但美国塑料工业协会的首席执行官拉多斯泽维斯基说第二项措施“没有成功的希望”。

拉多斯泽维斯基指出,塑料禁令只是政客发出的“高尚信号”,而且玻璃、金属和纸张在使用寿命中制造的污染更大。该协会的游说成员坚持不懈地向议员们传递类似的信息。协会在3月25日召开全国大会的通知中告诉成员单位:“不要让否定者主导塑料的故事。把我们已经知道的告诉国会山上的那些人,那就是塑料有助于改善人们的生活。”

尽管言辞激烈,但有迹象表明部分企业正在重新考虑塑料问题,部分原因是来自消费者施加的压力。

一些服装公司已经证明,回收塑料可以产生奢侈品溢价。2017年,阿迪达斯开始销售用马尔代夫海域中捞起的废塑料制造的高端运动鞋。这款标价200美元的运动鞋一直供不应求,而且去年阿迪达斯生产了1100万双这样的产品。该公司表明目前它计划将新塑料彻底从生产活动中剔除。耐克也已经在设计以回收聚酯纤维为原料的运动服,并计划推广此项措施。

包装食品领域的行为变化甚至有可能带来更大的影响。联合利华的首席执行官艾伦·乔普于去年10月表示,该公司将“从根本上重新考虑”自家产品的包装,并在2025年之前将新塑料使用量降低一半。联合利华的年塑料消耗量已经超过70万吨。

回收利用方面的进步也让人看到了希望。联合利华已经和沙特阿美旗下的SABIC合作,旨在创造使用化学回收方法的包装。他们表示,这个过程将二手塑料分解转化后生成的材料和新塑料一样好。去年,IBM称它已经创造出吞噬PET并将其变为塑料颗粒的化学工艺,和我们在马来西亚的收厂里看到的艰辛清洗和分拣工作相比,此项工艺的效率和可扩展性要高得多。

马来西亚一些回收厂的所有者在这些举措中看到了曙光,或者说他们的塑料颗粒再次成为受青睐商品的一丝希望。台湾资源回收公司Grey Matter Industries的运营长吴度泓说:“耐克和阿迪达斯想告诉消费者他们关心地球,而且将使用100%回收的塑料。”他指出,最近的这些公告或许预示着转折点的到来,“我们也想参与其中”。

在BioGreen Frontier,56岁的公司主管黄永文说他也希望跨国公司行为的改变能帮他拿下大生意。但同时,他对短期问题感到担心。黄永文仍在等待政府给他的工厂颁发批文,也面临着工厂关闭的风险。1月底,和很大一部分全球经济一样,BioGreen Frontier等回收公司受到了新冠疫情的沉重打击。中国在几周内关闭了工厂和港口,并且取消了回收塑料颗粒订单,这给回收公司带来了巨大的困难。2月中旬,黄永文在电话里告诉我,他已经开始在仓库里堆放塑料颗粒了,同时正在寻找新的客户。他说:“我不想把工人赶回家。”

这些工人来自世界上一些最贫穷的国家,他们继续涌进马来西亚,急于回收那些来自世界上一些最富裕国家的废品。对他们来说,尽管废塑料行业陷入了困境,但仍是收入阶梯上的一大进步。“我已经在这里工作两个月了。”站在BioGreen Frontier生产线上的Aung Aung有 25岁,来自缅甸仰光。他说塑料回收的工资远高于此前他在槟城餐馆的工作,“我得考虑我的家庭。”

与此同时,沙希德·阿里制定了远大的计划。他说自己会在BioGreen Frontier再工作两年,然后返还白沙瓦。“接下来我就会结婚。”他站在湿漉漉的、经过清洗的塑料中说,“我有一个心仪的女孩。”在那之前,他愿意每星期在回收线上工作84个小时——可以这样说,他正在废塑料上构建自己的家庭。

抵制塑料

我们对塑料的需求几乎没有止境,而地球消化塑料的能力有限。全世界只有9%的二手塑料得到回收,而每年倾倒进海洋的塑料约有800万吨。废塑料引发的公众愤慨日益高涨,从而推动企业采取大胆措施来解决这个问题。以下三种方法正越来越受欢迎。

1. 化学回收

塑料行业很看好这项解决全球塑料泛滥的策略。这种方法将通常要填埋或焚烧的塑料分解成最初的化学成分,这包括塑料包装袋、薄膜和咖啡胶囊。然后将这些化学成分和新树脂混合,从而做出跟新塑料一样坚固的材料。但它存在下行风险,比如说,这个过程会产生大量的碳,从而限制了它对气候的整体贡献。

2. 生物塑料

和石油原料制造的传统塑料不同,生物塑料的制造方法是从玉米或甘蔗中提炼出糖,然后将其转化为聚乳酸或聚羟基脂肪酸酯。这些材料的外观和触感非常像碳基塑料,但不消耗石化燃料。批评人士认为,用于制作生物材料的农作物需要喷洒杀虫剂,而且会占用本可种植粮食作物的土地。同时,回收生物塑料需要堆肥厂中的高热量,从而增加了二手生物塑料物品被填埋的风险。

3. 按包装付费

应对回收市场瘫痪的措施之一是要求企业向市政府付费,以便回收他们的塑料包装。大多数欧盟国家和一些亚洲国家已经制定了这样的法律。在美国,缅因州议会正在考虑类似的提案。塑料制造商表示他们更愿意提高回收率,而不是分担回收成本。但在欧洲,这样的法律已经开始促使企业减少包装并重新考虑对塑料的使用。(财富中文网)

Selvanaban Mariappen和塞巴斯蒂安·梅耶也为本篇报道做出了贡献

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年4月刊,标题为《恶性循环》。

译者: MS

This article is part of a Fortune Special Report: Business Faces the Climate Crisis. It was published in partnership with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Photography by Sebastian Meyer.

Cut into a hillside in northern Malaysia, amid oil palms and rubber trees, stands a large, open-air warehouse. This is the BioGreen Frontier recycling factory, which opened last November in the village of Bukit Selambau. On a searing-hot afternoon in January, Shahid Ali was working his very first week on the job. With his feet square in front of a chute on the production line, he stood knee-deep in soggy, white bits of plastic. Around him, more bits floated off the conveyor belt and fluttered to the ground like snowflakes.

Hour after hour, Ali sifts through the plastic jumble moving down the belt, picking out pieces that look off-color or soiled—rejects in the recycling process. Though it looks like backbreaking work, Ali says it is a great improvement over his previous job, folding bedsheets in a nearby textile factory, for much lower pay. Now, if he eats frugally, he can save money from his wages of just over $1 an hour and send $250 a month to his parents and six siblings in Peshawar, Pakistan, 2,700 miles away. “As soon as I heard about this work, I asked for a job,” says Ali, 24, a squat, bearded man with glasses and an easy smile. Still, he’s working 12 hours a day, seven days a week. “If I take a day off, I lose a day’s wages,” he says.

In the warehouse, hundreds of bales are stacked more than 60 feet high—each stuffed with plastic wrappers and bags tossed out weeks earlier by their original users. The address labels still stuck inside the bags offer clear clues to their origins. You can see toilet-tissue wrappers from a household in Half Moon Bay, Calif., packaging from El Paso, and polymeric film from energy-drink maker Red Bull’s U.S. headquarters in Santa Monica.

For this detritus, factories like Ali’s are the end of an odyssey of as much as 8,000 miles. The fact that the waste has traveled to this distant corner of the planet in the first place shows how badly the global recycling economy has failed to keep pace with humanity’s plastics addiction. This is an ecosystem that is deeply dysfunctional, if not on the point of collapse: About 90% of the millions of tons of plastic the world produces every year will eventually end up not recycled, but burned, buried, or dumped.

Plastic recycling enjoys ever-wider support among consumers: Putting yogurt containers and juice bottles in a blue bin is an eco-friendly act of faith in millions of households. But faith goes only so far. The tidal wave of plastic items that enters the recycling stream each year is increasingly likely to fall right back out again, casualties of a broken market. Many products that consumers believe (and industries claim) are “recyclable” are in reality not, because of stark economics. With oil and gas prices near 20-year lows—thanks in large part to the fracking revolution—so-called virgin plastic, a product of petroleum feedstocks, is now far cheaper and easier to obtain than recycled material. That unforeseen shift has yanked the financial rug out from under what was until recently a viable recycling industry. “The global waste trade is essentially broken,” says Graham Forbes, head of the global plastics campaign at Greenpeace. “We are sitting on vast amounts of plastic, with nowhere to send it and nothing to do with it.”

This gargantuan overload is creating a conflict that industry and government can no longer ignore—one that pits the profitability and usefulness of plastic against its threat to public health and the environment. There are few places where that conflict is more visible than in Malaysia. Here, rock-bottom wages, cheap land, and a still-evolving regulatory climate have enticed entrepreneurs to build hundreds of factories in a last-ditch bid to stay profitable. The real economic and environmental costs of plastic recycling are on vivid display, as I discovered traveling across the country with photographer Sebastian Meyer. Over the course of 10 days, we visited 10 recycling factories—some of them, including BioGreen Frontier, operating without official registration, under threat of a shutdown—as they grappled with waste shipped by the boatload from across the world. And we saw how the consequences of the broken plastics economy spill over into waste dumps, container dockyards, private homes, and out into the ocean.

For half a century, plastics have seen rocketing growth, for good reason: They are cheap, lightweight, and virtually indestructible. “There’s a great future in plastics,” a nervous young Benjamin Braddock (played by Dustin Hoffman) is told by a would-be mentor in the 1967 movie The Graduate. Acting on that tip would have yielded spectacular returns. Global production soared from 25 million tons a year in 1970 to more than 400 million tons in 2018.

Behind this polyethylene deluge is an economic colossus: a global plastics market worth about $1 trillion last year, according to U.K. data analysts the Business Research Co. Demand for plastics has doubled since 2000 and could double again by 2050. “We have a growing middle class around the world that needs to improve their quality of life,” says Keith Christman, managing director of plastic markets for the American Chemistry Council, an industry organization whose members include major producers like Dow, DuPont, Chevron, and Exxon Mobil. “Plastic is a part of that.” You can find plastic not just in your water bottles and sandwich bags, but in sweatshirts and wet wipes, home insulation and siding, chewing gum, tea bags, and countless other items.

Concerns about plastic have often been eclipsed by debates over carbon dioxide emissions. But the two are closely interlinked, with plastic production emitting considerable greenhouse gases itself. Now the world has fully awakened to the plastics crisis. Images of turtles choking on drinking straws or dead whales with stomachs engorged with plastic junk have gone viral—signifiers of the 8 million tons of plastic disgorged into oceans every year. (The UN Environment Program estimates that by 2050, the oceans will contain more plastic than fish.) The human toll is equally worrying. According to a study commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund, the average American consumes at least a teaspoon’s worth of plastic a week through food—roughly the amount in a credit card—with unforeseeable health consequences.

The durability that makes plastic so appealing, it turns out, also makes it an environmental time bomb. An estimated 90.5% of all the plastic produced since 1950 is still in existence, according to analysis by Roland Geyer, an industrial ecology professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. Only 8.4% of plastic waste in the U.S. was recycled in 2017, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. An additional 15.8% was burned to generate energy; the rest wound up in landfills. Recycling rates are even lower in parts of Asia and Africa. Even Europe, with its stringent environmental laws, recycles only about 30% of plastics.

For decades, plastics producers and their biggest customers—consumer-goods giants like Coca-Cola, Nestlé, PepsiCo, and Procter & Gamble—have argued that improving these recycling numbers is the solution to the plastic-waste crisis. They frame the problem as one of behavior—ours. “It’s a knee-jerk reaction to say the problem is with plastic,” Tony Radoszewski, president and CEO of the Plastics Industry Association, tells me. “The culprit is the consumer who does not dispose of products properly.”

It’s true that recycling rates are low. But to blame that fact on consumers alone is disingenuous. The bigger problem is a huge shift in energy markets. Prices for oil and natural gas have plummeted over the past decade. That in turn has made it far cheaper for petrochemical companies to produce virgin plastics than for factories to create recycled plastic. And with big profits to be made, companies have sharply increased virgin production, further driving down prices. Recycling used plastic is labor-¬intensive and therefore expensive—and the shifting economics now work against recycling in much of the world.

In 2018, this ecosystem endured another major blow when China halted the importation of almost all plastic scrap, saying that its own recycling industry was becoming an environmental hazard. The decision has caused chaos in the world’s plastic-resuscitation economy. Up until then, for example, the U.S. had been sending about 70% of its plastic waste to China. Now, “recycling is on life support,” says Mike Engelmann, solid waste coordinator for Smithtown, N.Y., a town of 120,000 people on suburban Long Island. “Hopefully things will turn around. But I am not sure how.”

One turnaround option, curbing the production and use of virgin plastics, faces long odds, given the petrochemical and energy industries’ political clout. Indeed, a thriving plastics market has become pivotal to the energy sector’s long-term health. As automakers transition to electric vehicles, and renewable energy takes off, plastics will pick up the slack in oil-and-gas industry growth, according to the International Energy Agency. It estimates that petrochemical feedstocks, much of which go to make plastics, could rise from 12% of total global oil demand today to 22% in 2040—at which point the agency says feedstocks could be the only segment of the industry that’s growing at all.

It’s no surprise, then, that big companies’ responses to consumer concerns don’t emphasize the supply side. In January, big players like Dow, DuPont, Chevron, P&G, and other major players launched the Alliance to End Plastic Waste. The plastics crisis “demands swift action from all of us,” P&G CEO ¬David Taylor told reporters.

But “swift action” did not include cutting production. Instead, companies committed to spending $1.5 billion over five years on projects to reclaim and recycle waste. Christman of the American Chemistry Council cites as one example the Renew Oceans project, which targets plastic pollution in India’s Ganges River. He says the alliance aims to make plastic packaging “100% recyclable” by 2030 and to make sure it all goes into the recycling stream by 2040. But when I ask who will bear the enormous cost of recycling such a mammoth amount, he hesitates, then says, “This will take funding. Part will come from industry, part from governments.”

Environmentalists say the sheer life span of plastics undermines that argument. What’s more, as Geyer’s research points out, most plastic that’s recycled after first use can’t be recycled again. Put another way: Almost every new piece of plastic we add to the planet may well stay here—along with almost all the old ones.

On a steamy afternoon, plastics trader Steve Wong sits at a small sidewalk eatery in the city of Ipoh, in central Malaysia. He’s meeting an old client, Saikey Yeong, CEO of local recycler AZ Plastikar. Under a roaring fan, the two men sit down to business over plates of spicy dumplings and pork rolls, washed down with jasmine tea. Their table is plastic, and so are their yellow chairs.

Wong takes out several bags and lays the contents in front of Yeong. In one are bits of clothing hangers he has collected from Paris fashion houses. In another is a tangle of plastic rope, the remnants of a polypropylene fishing net, which Wong acquired in the Netherlands. Hunched over the table, the men pull apart the net to check the polymers, at one point holding the flame of a plastic lighter up to the strands, to smell the smoke and determine its chemical makeup. “Look, this is good—we can recycle this, and there is a lot of it,” Wong tells Yeong. “The fishermen usually just dump this at the bottom of the sea.”

Wong is CEO of Fukutomi Recycling, a venerable name in the plastics industry, which he founded in 1984 in Hong Kong. He has the rough-and-ready mien of a door-to-door salesman, which, in a sense, he is. He spends much of his time traveling between the U.S., Europe, and Asia, attempting to match the hundreds of different polymers in plastic waste with whichever factories can process them. It is in settings like these—over $5 lunches and endless pots of tea, rather than in sleek corporate boardrooms—that crucial recycling deals are really decided. (On another afternoon, at another meeting, a Chinese factory owner plied Wong with homemade rice wine. As his wife cooked up a spread of Chinese dishes for us, he and Wong tested plastic samples in a rickety toaster oven.)

In Ipoh, Yeong agrees to buy about 600 tons of the polypropylene each month, for about $228,000 a month. But he fears being stuck with depreciating stock—a common experience these days. “Producing new plastic is so much cheaper than recycling,” Yeong says. “It is a very big problem for us.”

In factories across Malaysia, we hear similar tales. “If you came to me now and asked me to start this business, you had better just kill me,” says Yap Koon Fatt, 59, managing director of YB Enterprise, miming a gun to his head. Yap’s 10-acre recycling factory is set among oil palm trees in his hometown of Padang Serai, where he started recycling at 17. He currently recycles about 1,000 tons of plastic a month. But prices for his products have dropped 20% over the past six months, and Chinese orders have dropped by half.

In the Fizlestari factory, in Nilai, south of Kuala Lumpur, enormous bales of used water and juice bottles from Australia, the U.S., and Britain sit stacked to the ceiling. The factory brought in about $10 million in revenue last year, but its finished product sells for 25% less than in 2017, when the factory opened. “Prices have dropped a lot, a lot, a lot,” CEO Cecil Chan tells me. “And I don’t see them going back up anytime soon.”

Wong, 62, has heard it all before, and he too is feeling the economic pain. He began as a boy in Hong Kong—“I was in primary school, not even teenage years,” he says—collecting trash for his father’s small recycling operation. He eventually grew the business into a profitable enterprise, and in 2000 he moved his wife and six children to Diamond Park, Calif. By then Wong operated more than 20 factories across the world, including in Germany, Britain, South Africa, and Australia. He says that most years he made $10 million in profit from his Hong Kong operation alone. Like most recyclers, his biggest market was China.

That all came crashing down in 2018, when China launched the ban it calls Operation National Sword. The country had long allowed enormous quantities of plastic-waste imports. But the vibrant industry that sprang up to process that waste eventually prompted complaints about the pollution it generated. Today, China will accept only waste that’s almost completely uncontaminated—¬a threshold barely 1% of items can clear. Globally, about 111 million tons of plastic waste will need to find other destinations within the next decade, according to the University of Georgia College of Engineering.

China’s actions shut the pipeline that had made Wong rich. He estimates his business has plummeted more than 90% since National Sword, and he has closed all but five of his factories. Now he makes most of his livelihood as a middleman, brokering waste to the thousands of recyclers that have opened in response to China’s drastic change. Many have relocated from China to Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia, drawn by cheap land—and even cheaper labor, in the form of migrants from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Myanmar.

Venturing into the factories of Wong’s customers shows just how labor-intensive the work can be and why communities might not want the factories as neighbors.

Inside, workers comb through containerloads of plastic waste. They sort through used plastic, separating materials such as PET (polyethylene terephthalate), which is widely used in drinking bottles and packaging, and LDPE (low-density polyethylene), the plastic in throwaway shopping bags. Each of the hundreds of polymers requires different processing. Once sorted, the waste is machine-washed and turned into yarn-like string. The string is then fed into a grinder, which turns it into pellets the size of grains of rice, known as nurdles. Recyclers pack the pellets into bales and sell them back to manufacturers as raw material. Much of the supply goes to factories in China, where it reenters the consumerism bloodstream as material for car parts, toys, water bottles, and thousands of other products.

The process is remarkable—but it has never been close to 100% efficient. Many polymers that users try to recycle are too low-grade for manufacturing. Soiled and damaged plastics often can’t be repurposed. And the price pressures created by the virgin plastic glut have only disrupted things further. “At the moment, there is no economic value to recycle this,” says Muralindran Kovindasamy, operations director in Ipoh for ResourceCo Asia, an Australian company. He buys some of the plastic Malaysian factories can’t use and sells it to cement companies as material for road paving. Most other recyclers simply burn or bury it. “Enforcement is poor,” he says, “and it’s cheap to dump it in the landfill.”

Yeo Bee Yin, then Malaysia’s environment minister, looked almost pained when I asked her how quickly Malaysia’s plastic-scrap trade has grown. Sitting in her top-floor office in the federal administrative center, Putrajaya, Yeo estimated that the trade contributes only $1 billion a year to the economy. Yet she saw herself as waging an all-out war against the operators. Malaysian recyclers require 19 different environmental permits to operate, and Yeo closed more than 200 factories last year alone, for lack of paperwork. If need be, she said, the government should “cut their electricity, cut their water, cut everything that is possible. They are gangsters.”

Yeo’s war awaits a new general: A few weeks after we spoke, she resigned with the rest of Malaysia’s cabinet amid a parliamentary crisis. But whoever succeeds her will have allies among health experts and ordinary citizens, for reasons evident even to the casual observer.

On our first morning in Malaysia, Sebastian Meyer and I climb a plastic mountain 50 feet high in the heart of Sungai Petani, a town of about 200,000 people near the island of Penang. This waste dump comprises plastics that nearby factories have deemed unrecyclable. It is the very end of the plastic supply chain. Burning it seems about the only next step, and someone is doing just that. Tneoh Shen Jen, a physician who directs the city’s Metro Hospital, says residents have experienced breathing problems as factories repeatedly and illegally burn the waste; they “smell burning plastic most nights,” he says.

In a neighborhood nearby, Tei Jean, 40, sits in her living room with her 6-year-old daughter. Their windows are sealed, and the house is stripped of toys, blankets, and curtains. It is a desperate effort by Tei to stop the girl’s respiratory infections, which she says began soon after recycling factories opened in their area last year. The girl has been hospitalized three times since then and last year stayed home from school for six months. “She kept getting worse,” Tei says. “Every time she left the house, her eyes would turn red.” Now the girl spends her days in the quiet, dark living room, drawing at a small pink table.

After protests from activists in Sungai Petani, factory owners stopped burning plastic last fall. But the two sides remain hostile. Last April, arsonists set ablaze two factories overnight. Their owners blame environmental groups. When we visited the town dump, a security guard snapped our photograph with his phone, then texted it to factories across Malaysia, to alert them to our presence. For days after, factory owners eyed us with suspicion, asking, “Are you with the environmentalists?”

On one occasion, we were. One day, near Sungai Petani, two activists guided us down a dirt road that ran alongside the Mudah River, a source of water for local farms. There, a short walk from a kindergarten, a large, unlicensed dump had sprung up. A chemical reek wafted up from pools of orange-colored water, filled with plastics instantly recognizable to Western consumers: Tide laundry soap bottles, Poland Spring water bottles, Green Giant frozen-pea packets. Locals explained that recyclers had discarded unwanted stocks here, in violation of Malaysian law. When a dump-truck driver spotted us, he hurriedly left the area. (Two days later, the site was set alight; local newspapers showed photos of thick black smoke rising over the trees.)

Malaysians hope to defend themselves from some of these depredations with the help of the Basel Convention on hazardous waste, which goes into effect next January. The convention bars the shipment of plastic contaminated with any kind of waste, and it has been signed by almost every country in the world—though not the U.S.

Malaysian officials have already begun blocking containers that they suspect violate the rules. On a blustery Sunday afternoon, customs officials escort us around Penang’s dockyard, showing us which containers are marked for return to the U.S., France, and Britain—at the shippers’ expense. Those returns can quickly get mired in a bureaucratic labyrinth, however. One container from Oakland, marked for repatriation, has sat on the dockside in Penang since June 2018.

Yeo, the former minister, believes plastic waste imports should be limited until the new Basel rules are strictly enforced, not only in Malaysia but also in nearby recycling hubs like the Philippines and Indonesia. People are increasingly rankled by the trade, she says. “Why are we a dumping ground for you? Because it is more convenient for you?” she asks me. “The feeling is there is perhaps injustice in it.”

In truth, few people give even a passing thought to where their trash goes. Most assume that after they wheel their garbage bins to the sidewalk, a well-oiled recycling system takes over.

Early one January morning, we tracked Smithtown’s garbage trucks as they proved how far off the mark that assumption is. On the first recycling day of 2020, the trucks tipped out 103 tons of plastic at a collection center that was once a full-service recycling facility. In 2014, Smithtown earned about $878,000 selling its waste to eager recyclers. Now, they pay nearly $80,000 a year to get disposal companies to take it off their hands.

Smithtown’s difficulties typify what has happened across the U.S.—and they predate China’s ban. As oil and gas prices crashed, the market for the town’s used plastic dried up; virgin plastic was simply cheaper. So it drastically cut its recycling and now accepts only higher-quality polymers, called “ones” and “twos”—the numbers inside the triangle recycling icon. Lower-grade plastics, numbered three to seven, are no longer marketable. Hundreds of towns across the U.S. have made similar decisions, and dozens have simply stopped curbside recycling altogether.

These days, a trucking company collects Smithtown’s plastic waste and delivers it to the Sims Municipal Recycling Center in Brooklyn. Since Long Island, where Smithtown is located, bans solid-waste landfilling, many low-grade plastics wind up being burned for electricity at a plant in nearby Huntington. Actual recycling of the waste is almost out of the question, says Smithtown sanitation supervisor Neal Sheehan. “It is still cheaper to ship it across the world to someplace, to come back as something,” he says.

If current trends continue, that’s unlikely to change. Oil and gas companies are making major investments in a future virgin-plastic boom. Multinational goliath Royal Dutch Shell is building a mammoth complex near Pittsburgh—one of America’s fracking epicenters—that will produce about 3.5 billion pounds a year of polyethylene plastic. (The plant won a 25-year tax break from the Pennsylvania state legislature that’s worth an estimated $1.6 billion.) In January, Taiwan’s Formosa Plastics Group won approval from state lawmakers to build a $9.4 billion plastic-production complex in Louisiana, which it says will create 1,200 jobs.

These plants are an environmental problem in their own right. The Center for International Environmental Law, an advocacy group, argues that the industry’s expansion could pose “a significant and growing threat to the earth’s climate.” It calculates that the greenhouse gases emitted in the production of plastics will equal the output of about 615 new coal plants by 2050. And Geyer, the UC–Santa Barbara professor, estimates that by then, the world will be creating more than 1.1 billion tons of virgin plastic a year.

Geyer says that after years of studying industry data, he has reached one conclusion. “There is one thing we absolutely must do, and it is also the hardest,” he says. “We have to commit ourselves to stop growing the production of virgin plastic.”

Yet plastic producers’ capacity to resist that outcome seems as sturdy as a laundry-soap bottle, especially in the U.S. Bans on bags and other “single use” plastics are a case in point. Beginning in 2021, single-use plastics will be strictly controlled in the European Union’s 27 countries, and plastic bags will be banned in major cities in China. In the U.S., petrochemical companies have largely stymied such proposals. Only eight U.S. states ban single-use plastics. At the national level, a measure introduced in February by two Democratic U.S. senators would make companies share the burden of recycling and impose a moratorium on virgin-plastic growth. But Rado¬szewski, CEO of the Plastics Industry Association, calls the second measure “a nonstarter.”

Radoszewski says plastic-ban proposals are simply “virtue signaling” by politicians, and argues that alternatives like glass, metal, and paper are more polluting over their life span. The association lobbies relentlessly to send similar messages to lawmakers. “Don’t let naysayers dictate the story of plastics,” the group told its members in announcing its national conference on March 25. “Educate those on Capitol Hill about what we already know: Plastics help change people’s lives for the better.”

For all the fighting words, there are signs that some businesses are rethinking plastics—in part because of pressure from concerned customers.

Some clothing companies have proved that recycled plastics can command a luxury premium. In 2017, Adidas began selling high-end sneakers made of plastic waste hauled from the ocean off the coast of the Maldives. The $200 shoes have been a sold-out hit, and Adidas made 11 million pairs last year. The company says it now aims to eliminate virgin plastic from its production completely. Nike has also designed sportswear from recycled polyester and plans to expand that effort.

Behavioral changes in the packaged-goods world could have an even bigger impact. Unilever CEO Alan Jope said last October that the company would “fundamentally rethink” its packaging—its plastic footprint exceeds 700,000 tons a year—and halve virgin-plastic use by 2025.

Advances in recycling also show promise. Unilever has partnered with SABIC, a company owned by Saudi Aramco, to create packaging using chemical recycling, a process that breaks down used plastics and converts them into material it says is as good as virgin. And IBM last year said it had created a chemical process to eat through PET and turn it into nurdles—in a process it says is far more efficient and scalable than the painstaking washing and sorting in factories like the ones we visited in Malaysia.

Several owners of those factories see promise in these moves—a glimmer of hope that their nurdles might finally become desirable commodities again. “Nike and Adidas want to tell customers they care about the earth and will use 100% recycled plastics,” says Adu Wu, chief operating officer for Grey Matter Industries, a Taiwanese recycler. The recent announcements might signal a turning point, he says. “We want to be part of that.”

Back at BioGreen Frontier, company director Engboon Ooi, 56, says he too hopes changing behavior among multinationals could help him land big deals. In the meantime, he’s preoccupied with short-term woes. Ooi is still waiting for official permits for his factory and risks being shut down. And in late January, BioGreen and other recyclers, like much of the global economy, were hit with a body blow from the coronavirus. Within weeks, China shut down factories and ports and canceled orders for recycled-plastic pellets, causing havoc for recyclers. By phone in mid-February, Ooi told me he has begun stockpiling nurdles in the warehouse, while hunting for other clients. “I don’t want to send the workers home,” he says.

Those workers continue to flood into Malaysia from some of the world’s poorest countries, eager to recycle the waste from some of its richest. For them, the plastic-waste industry, even in its depressed state, remains a large step up the economic ladder. “I have worked here for two months,” says Aung Aung, 25, from Yangon, Myanmar, as he stands on the BioGreen production line. He says recycling plastic pays far more than his previous restaurant jobs in Penang. “I need to think about my family,” he says.

Shahid Ali, meanwhile, has big plans. He says he will work at BioGreen for two more years before returning to Peshawar. “I will get married then,” he says, standing amid the sodden washed plastic. “I have already chosen a girl.” Until then, he’s willing to spend 84 hours a week on the recycling line—building a home, figuratively speaking, out of plastic scraps.

Pushing Back on Plastic

Our appetite for plastic is almost limitless; the planet’s ability to absorb it is not. Barely 9% of used plastics are recycled worldwide, and about 8 million tons are dumped into the oceans every year. A growing wave of popular anger over plastic waste is pushing companies to take bolder steps to tackle the problem. These three approaches are gaining momentum.

1. Chemical recycling

The plastics industry is bullish on this strategy to address the global glut. The method involves breaking down plastics that are typically landfilled or burned, like plastic wrappers, film, and coffee pods, into their raw chemical ingredients. Those are then mingled with virgin resins to make materials that are just as strong as new plastic. There are downsides, however. The process generates a substantial carbon footprint, for example, limiting its overall benefit to the climate.

2. Bioplastics

Unlike traditional plastic, which is made from petroleum feedstocks, bioplastics are produced by extracting sugar from corn or sugarcane and turning it into polylactic acids or polyhydroxyalkanoates. Those materials look and feel much like carbon-based plastics, without the fossil fuel consumption. Critics note that crops for bioplastics require pesticides and hog land on which food could be grown. And recycling bioplastics requires high heat in composting plants, increasing the risk that used items will be landfilled.

3. Pay-per-package

One way to counteract a broken recycling market: require companies to pay city governments to recycle their plastic packaging. In most of the European Union and some Asian countries, such laws already exist. In the U.S., Maine’s legislature is considering a similar bill. Plastic makers say they would prefer to boost recycling rates rather than shoulder the costs. But in Europe, the laws have helped spur companies to cut packaging and rethink their use of plastic.

With additional reporting by Selvanaban Mariappen and Sebastian Meyer

A version of this article appears in the April 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline “Vicious (Re)cycle.”