在4月底与华尔街交谈时,可口可乐公司的首席执行官詹鲲杰祭出了与越来越多同僚相似的口吻,而且做了一些此前对于《财富》美国500强领导者来说并不怎么常见的事情:他放弃了。这位首席执行官在预测这家饮料巨头未来几个月的业绩时宣称,自己做不到。詹鲲杰在公司的第一季度营收电话会议上说:“我们意识到当前的状况真的是前所未有。鉴于当前环境中巨大的不确定性,我们认为推迟发布2020财年指引是审慎之举。”

今春,标普500榜单中定期提供营收指引的100多家公司,包括IBM、英特尔和金佰利,均表示不会尝试预测2020年业绩。

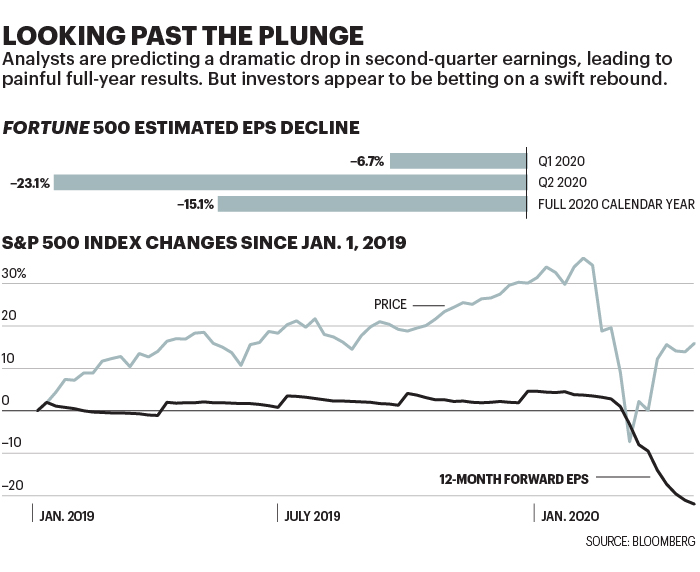

鉴于上市公司缺乏可视度,对公司利润扑朔迷离的前景感到困惑也实属正常。不过,股市一直都释放着相反的信号。在大盘于2月中旬达到创纪录的新高之后,标普500下跌了34%,投资者明显担心疫情会导致收益出现长时间的大幅下跌。然后,股市在4月大幅反弹(自1987年以来最好的一个月),让市值重回历史高点。当前的股价意味着,在约18个月之后,利润将创历史新高。

这里有一个让公司和投资者感到困惑的关键问题:当经济回归,商品和服务的产出重回疫情之前的水平时,利润将何去何从?

有关GDP在何时完全恢复的估算存在很大的差别。其中有一个合理的预测来自于美国银行,它认为GDP将在2021年年底恢复到2019年的水平。不过美国银行的预测较为乐观:按年率计算,经济生产在2020年第一季度下跌了4.8%,是大萧条以来受影响最严重的第一季度。华尔街经济师预计,二季度将出现高达两位数的跌幅。

即便GDP按照最理想的轨迹发展,企业的收益在经济最终恢复时也有可能会大幅低于去年的峰值水平。原因有两个。第一,包括航空、能源和商业地产在内的重点行业将受累于此类严重的结构性破坏,因此这些行业要恢复此前盈利能力所需的时间就会长的多。第二,大型公司的盈利水平远不能达到近些年的水平,因为在低廉的劳动成本与坚挺的消费者的共同推动下,利润率已经升至难以为继的高度。

大逆转

企业收益在疫情之前一路高歌。去年,标普500企业经营利润总额达到了1.3万亿美元,较2016年增长了44%。在同一时间跨度中,《财富》美国500强基于GAAP(美国通用会计准则)标准的收益从8900亿美元升至1.2万亿美元,创历史新高。这两个指标有众多重叠的地方:在任何给定年份,约330家公司同时会出现在标普500和《财富》美国500强企业榜单中,后者包括非上市公司。通过研究分析师对标普的预测,我们便可以推断《财富》美国500强企业的未来走向。

如果审视一下标普500榜单中11个行业领域的利润组成,我们会发现,近些年大多数的增幅来自于少数行业。从2016年到2019年,标普500中66家金融类企业(由摩根大通和美国银行引领)的利润占比从18%升至25%。来自于传播服务(涵盖26家公司,包括Facebook、Alphabet和康卡斯特)的利润占比从3%升至10%。与此同时,工业、日常消费品和非必须消费品公司(几乎包含了旧经济中的支柱行业)的合计盈利占比从此前的三分之一降至24%。

在2020年的前两个月,这趟盈利快车依然滚滚向前。PNC Financial Services Group的首席投资策略师阿曼达·阿加提称:“2019年底贸易争端的停火给利润提供了新的增长动力。我们预计今年的每股收益会出现10%的增幅。”随后,新冠疫情席卷了整个世界。

标普和FactSet开展的收益预估调查显示,新冠疫情导致的美国店面关闭引发了大萧条以来最严重的下跌。FactSet在5月初的报告显示,分析师预测第一季度每股收益将出现同比13.6%的下滑,第二季度将出现40.6%的暴跌。业界一致认为,即便下半年经济会出现反弹,公司的年底利润较2019年同期依然将下滑19.7%。华尔街预测,金融类企业的收益将暴跌38%,从2520亿美元跌至1580亿美元;工业类企业收益将从1250亿美元跌至730亿美元,跌幅达42%;能源行业在近些年来对于整体收益贡献并不大,仅贡献了520亿美元,占标普企业总收益额的3.8%。原油价格今年的暴跌——从1月的60美元/桶跌至4月底的12美元/桶,将抹杀上述贡献额。分析师预计,今年能源行业将出现49亿美元的亏损。

几乎可以肯定的是,即便这些可怕的预测看起来依然过于美好。分析师通常都会过度乐观,而且不好的消息也是接踵而至,各项预估值也是在以创纪录的速度下滑。自进入4月以来,FactSet的第一季度预测值已经翻了五番,从-3.3%达到了-19.7%。例如,考虑到达美航空有关其营收将在第二季度暴跌90%的警告,要平衡这类崩盘式的下跌则需要大量出乎意料的惊喜。

美银美林的董事总经理萨维塔·萨布拉曼尼安提出了一个更现实的看法,她预测2020年标普每股收益将下滑29%。她认为,随着经济的反弹,利润将出现延迟,很大一部分原因在于公司和消费者的消费方式在危机结束时会发生变化。由于失业率已经飙升至自大萧条以来的最高水平,家庭将对包括下饭馆和汽车在内的一切开支变得更加谨慎。高管们在见识了其雇员在家工作的生产效率之后,将重新思考保留大型、昂贵办公室的必要性。萨布拉曼尼安说:“这是我们的分析师从他们负责的公司听来的消息,而且小企业主也向我们的私有银行部门讲述了类似的故事。”这一趋势有可能会对租金和商业地产的利润带来不利影响。

而航空公司重回其疫情前的状态将是一个十分缓慢的过程,尤其在眼下,整个商界都只能通过Zoom这类软件来进行会面。萨布拉曼尼安说:“休闲旅行可能会回归正常,但商业差旅会减少。高管们将审视前往中国、欧洲出差的必要性。”

自然而然,为居家工作和购物提供服务的行业将成为主要受益者,其收益将部分抵消疫情带来的破坏,这一情景已经开始上演。例如,自3月中旬以来,微软的Teams视频协作服务的活跃用户已从4400万跃升至7500万。其云服务以及针对居家员工的交流技术的销售额不断增长,让微软获益良多。这一需求帮助推动这家软件巨头的一季度经营收入增长了25%。

然而,数字领域赢家的提振作用并不足以抵消利润的普遍疲软,至少在短期内是如此。问题在于利润率。穆迪分析的首席经济师马克·赞迪预测,海外销售的盈利能力将大幅下滑,而这笔收入去年占标普500总收益的比例超过了40%。他指出,中国的增速也在放缓,欧洲和新兴市场的反弹速度可能远低于美国。美国求职者的增加将放缓劳动力成本的增长步伐,但并不足以改变航空公司、餐馆以及酒店为挽回顾客而不得不不断压低的价格。

总结

如果GDP在2021年确实回归去年的水平,那么盈利呢?2019年第四季度的运营利润率为11.4%,比过去10年的中值高出了近3个百分点。我们不妨简化一下,并预测回归后的利润会略高于平均水平,也就是销售额的9%。在这种情况下,标普500企业的收益将比2019年低20%,2019年的每股收益为163美元。我估计,2021年年底的每股收益将达到130美元。

这个结果将令华尔街大失所望。FaceSet在5月调查的分析师预测,标普500的每股盈利在2021年将达到168美元,而标普自身的调查称这个数字为165美元。不过,数学和逻辑显示,即便在最好的情况下,这些预测结果都十分牵强。数个月前,利润经历了其梦幻般的时期,但短期内回归这一水平的可能性不大。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年6/7月刊,标题为《万亿美元问题:利润何时才能止跌?》。

译者:Feb

在4月底与华尔街交谈时,可口可乐公司的首席执行官詹鲲杰祭出了与越来越多同僚相似的口吻,而且做了一些此前对于《财富》美国500强领导者来说并不怎么常见的事情:他放弃了。这位首席执行官在预测这家饮料巨头未来几个月的业绩时宣称,自己做不到。詹鲲杰在公司的第一季度营收电话会议上说:“我们意识到当前的状况真的是前所未有。鉴于当前环境中巨大的不确定性,我们认为推迟发布2020财年指引是审慎之举。”

今春,标普500榜单中定期提供营收指引的100多家公司,包括IBM、英特尔和金佰利,均表示不会尝试预测2020年业绩。

鉴于上市公司缺乏可视度,对公司利润扑朔迷离的前景感到困惑也实属正常。不过,股市一直都释放着相反的信号。在大盘于2月中旬达到创纪录的新高之后,标普500下跌了34%,投资者明显担心疫情会导致收益出现长时间的大幅下跌。然后,股市在4月大幅反弹(自1987年以来最好的一个月),让市值重回历史高点。当前的股价意味着,在约18个月之后,利润将创历史新高。

这里有一个让公司和投资者感到困惑的关键问题:当经济回归,商品和服务的产出重回疫情之前的水平时,利润将何去何从?

有关GDP在何时完全恢复的估算存在很大的差别。其中有一个合理的预测来自于美国银行,它认为GDP将在2021年年底恢复到2019年的水平。不过美国银行的预测较为乐观:按年率计算,经济生产在2020年第一季度下跌了4.8%,是大萧条以来受影响最严重的第一季度。华尔街经济师预计,二季度将出现高达两位数的跌幅。

即便GDP按照最理想的轨迹发展,企业的收益在经济最终恢复时也有可能会大幅低于去年的峰值水平。原因有两个。第一,包括航空、能源和商业地产在内的重点行业将受累于此类严重的结构性破坏,因此这些行业要恢复此前盈利能力所需的时间就会长的多。第二,大型公司的盈利水平远不能达到近些年的水平,因为在低廉的劳动成本与坚挺的消费者的共同推动下,利润率已经升至难以为继的高度。

大逆转

企业收益在疫情之前一路高歌。去年,标普500企业经营利润总额达到了1.3万亿美元,较2016年增长了44%。在同一时间跨度中,《财富》美国500强基于GAAP(美国通用会计准则)标准的收益从8900亿美元升至1.2万亿美元,创历史新高。这两个指标有众多重叠的地方:在任何给定年份,约330家公司同时会出现在标普500和《财富》美国500强企业榜单中,后者包括非上市公司。通过研究分析师对标普的预测,我们便可以推断《财富》美国500强企业的未来走向。

如果审视一下标普500榜单中11个行业领域的利润组成,我们会发现,近些年大多数的增幅来自于少数行业。从2016年到2019年,标普500中66家金融类企业(由摩根大通和美国银行引领)的利润占比从18%升至25%。来自于传播服务(涵盖26家公司,包括Facebook、Alphabet和康卡斯特)的利润占比从3%升至10%。与此同时,工业、日常消费品和非必须消费品公司(几乎包含了旧经济中的支柱行业)的合计盈利占比从此前的三分之一降至24%。

在2020年的前两个月,这趟盈利快车依然滚滚向前。PNC Financial Services Group的首席投资策略师阿曼达·阿加提称:“2019年底贸易争端的停火给利润提供了新的增长动力。我们预计今年的每股收益会出现10%的增幅。”随后,新冠疫情席卷了整个世界。

标普和FactSet开展的收益预估调查显示,新冠疫情导致的美国店面关闭引发了大萧条以来最严重的下跌。FactSet在5月初的报告显示,分析师预测第一季度每股收益将出现同比13.6%的下滑,第二季度将出现40.6%的暴跌。业界一致认为,即便下半年经济会出现反弹,公司的年底利润较2019年同期依然将下滑19.7%。华尔街预测,金融类企业的收益将暴跌38%,从2520亿美元跌至1580亿美元;工业类企业收益将从1250亿美元跌至730亿美元,跌幅达42%;能源行业在近些年来对于整体收益贡献并不大,仅贡献了520亿美元,占标普企业总收益额的3.8%。原油价格今年的暴跌——从1月的60美元/桶跌至4月底的12美元/桶,将抹杀上述贡献额。分析师预计,今年能源行业将出现49亿美元的亏损。

几乎可以肯定的是,即便这些可怕的预测看起来依然过于美好。分析师通常都会过度乐观,而且不好的消息也是接踵而至,各项预估值也是在以创纪录的速度下滑。自进入4月以来,FactSet的第一季度预测值已经翻了五番,从-3.3%达到了-19.7%。例如,考虑到达美航空有关其营收将在第二季度暴跌90%的警告,要平衡这类崩盘式的下跌则需要大量出乎意料的惊喜。

美银美林的董事总经理萨维塔·萨布拉曼尼安提出了一个更现实的看法,她预测2020年标普每股收益将下滑29%。她认为,随着经济的反弹,利润将出现延迟,很大一部分原因在于公司和消费者的消费方式在危机结束时会发生变化。由于失业率已经飙升至自大萧条以来的最高水平,家庭将对包括下饭馆和汽车在内的一切开支变得更加谨慎。高管们在见识了其雇员在家工作的生产效率之后,将重新思考保留大型、昂贵办公室的必要性。萨布拉曼尼安说:“这是我们的分析师从他们负责的公司听来的消息,而且小企业主也向我们的私有银行部门讲述了类似的故事。”这一趋势有可能会对租金和商业地产的利润带来不利影响。

而航空公司重回其疫情前的状态将是一个十分缓慢的过程,尤其在眼下,整个商界都只能通过Zoom这类软件来进行会面。萨布拉曼尼安说:“休闲旅行可能会回归正常,但商业差旅会减少。高管们将审视前往中国、欧洲出差的必要性。”

自然而然,为居家工作和购物提供服务的行业将成为主要受益者,其收益将部分抵消疫情带来的破坏,这一情景已经开始上演。例如,自3月中旬以来,微软的Teams视频协作服务的活跃用户已从4400万跃升至7500万。其云服务以及针对居家员工的交流技术的销售额不断增长,让微软获益良多。这一需求帮助推动这家软件巨头的一季度经营收入增长了25%。

然而,数字领域赢家的提振作用并不足以抵消利润的普遍疲软,至少在短期内是如此。问题在于利润率。穆迪分析的首席经济师马克·赞迪预测,海外销售的盈利能力将大幅下滑,而这笔收入去年占标普500总收益的比例超过了40%。他指出,中国的增速也在放缓,欧洲和新兴市场的反弹速度可能远低于美国。美国求职者的增加将放缓劳动力成本的增长步伐,但并不足以改变航空公司、餐馆以及酒店为挽回顾客而不得不不断压低的价格。

总结

如果GDP在2021年确实回归去年的水平,那么盈利呢?2019年第四季度的运营利润率为11.4%,比过去10年的中值高出了近3个百分点。我们不妨简化一下,并预测回归后的利润会略高于平均水平,也就是销售额的9%。在这种情况下,标普500企业的收益将比2019年低20%,2019年的每股收益为163美元。我估计,2021年年底的每股收益将达到130美元。

这个结果将令华尔街大失所望。FaceSet在5月调查的分析师预测,标普500的每股盈利在2021年将达到168美元,而标普自身的调查称这个数字为165美元。不过,数学和逻辑显示,即便在最好的情况下,这些预测结果都十分牵强。数个月前,利润经历了其梦幻般的时期,但短期内回归这一水平的可能性不大。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年6/7月刊,标题为《万亿美元问题:利润何时才能止跌?》。

译者:Feb

Speaking to Wall Street in late April, Coca-Cola CEO James Quincey followed the example of a growing number of his peers and did something previously unusual for a Fortune 500 leader: He threw up his hands. Forecasting the beverage giant’s results in the months ahead, the chief executive declared, was well-nigh impossible. “We recognize that these are truly unprecedented times,” said Quincey, on the company’s first-quarter earnings call. “Given the great uncertainty of the current environment, we feel it’s prudent to hold off providing fiscal-year 2020 guidance.”

This spring, more than 100 companies in the S&P 500 that regularly provide earnings guidance—including IBM, Intel, and Kimberly-Clark—have said they won’t attempt to forecast results for 2020. Putting a number on just how badly the coronavirus crisis will batter their businesses is too hard to calculate with any degree of accuracy.

Given that lack of visibility at publicly traded companies, you can be forgiven for getting flummoxed by the confusing outlook for corporate profits. The stock market certainly has been flashing conflicting signals. After hitting an all-time high in mid-February, the S&P 500 collapsed 34%, with investors evidently fearing the pandemic would cause a long, steep fall in earnings. But then a massive April rally—the best month for stocks since 1987—drove the market’s valuation back to a historically high level. Current prices imply that, in 18 months or so, profits will be better than ever.

Here’s the overriding question vexing both companies and investors: Where will profits stand when the economy returns to generating the same output of goods and services as before the outbreak?

Estimates of when GDP will fully recover vary widely. A reasonable forecast is Bank of America’s view that GDP will regain 2019 levels by the end of 2021. Keep in mind that the BofA forecast is optimistic: Economic production shrank at a 4.8% annual rate in the first quarter of 2020—the biggest one-quarter hit since the Great Recession. And Wall Street economists foresee a steep double-digit drop in the second quarter.

Even if GDP follows that best-case trajectory, the likelihood is that earnings will be significantly lower when the economy finally recovers than at their record peak last year. The reason is twofold. First, key industries such as airlines, energy, and commercial real estate will suffer such severe structural damage that they’ll take far longer to return to their old profitability. Second, big companies won’t be nearly as profitable as in recent years, when a confluence of low labor costs and a buoyant consumer swelled margins to unsustainable levels.

A sharp reversal

Earnings were rocketing up before the pandemic. Last year, total operating profits for the S&P 500 hit $1.3 trillion, up 44% from 2016. Over the same span, GAAP earnings for the Fortune 500 rose from $890 billion to $1.2 trillion—an all-time high. The two benchmarks have a lot of overlap: In any given year, about 330 companies are on both the S&P 500 and the Fortune 500, the latter of which includes non–publicly traded companies. By digging into what analysts predict for the S&P, we can extrapolate the future direction of the Fortune 500 as well.

A careful look at the profit mix of the S&P 500’s 11 industry sectors reveals that much of the gains in recent years came from a handful of industries. From 2016 through 2019, the share of profits earned by the 66 “financials” in the S&P 500—led by JPMorgan and Bank of America—jumped from 18% to 25%. And the portion from communication services, a category encompassing 26 companies including Facebook, Alphabet, and Comcast, more than tripled from 3% to 10%. Meanwhile, industrials, consumer staples, and consumer discretionary companies—sectors that are home mostly to old-economy stalwarts—dropped from a combined one-third of total earnings to 24%.

For the first two months of 2020, the earnings express kept rolling. “The halt to the trade war in late 2019 gave profits new impetus,” says Amanda Agati, chief investment strategist at PNC Financial Services Group. “We were expecting 10% gains in earnings per share this year.” Then COVID-19 swept around the globe.

The coronavirus shutdown in the U.S. precipitated the deepest drop since the Great Recession in polls of earnings estimates conducted by S&P and FactSet. According to ¬FactSet’s report from early May, analysts are forecasting a 13.6% earnings-per-share (EPS) decline in the first quarter, compared with a year earlier, and a 40.6% stumble in the second. The consensus is that a second-half rebound will leave profits 19.7% lower at year-end than at the close of 2019. The Street predicts that earnings for financials will plunge 38%, from $252 billion to $158 billion. And industrials are forecast to shrink from $125 billion to $73 billion—a 42% drop. Energy has been a minor contributor to overall earnings in recent years, adding just $52 billion, or 3.8%, of the S&P total in 2019. And the tumble in oil prices this year—from $60 per barrel in January to $12 in late April—will obliterate that figure. Analysts expect a $4.9 billion loss in energy this year.

It’s a near certainty that even those dire forecasts are too rosy. Analysts are always overly optimistic, and the parade of bad news is so relentless that estimates are falling at record speed. Since the start of April, FactSet’s forecast for the first quarter has sunk sixfold—from negative 3.3% to that negative 19.7%. Consider, for example, Delta’s warning that its revenues will crater 90% in the second quarter. It take a lot of upside surprises to balance out those kinds of collapses.

A more realistic take comes from Savita Subramanian, managing director at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, who predicts a 29% drop in S&P earnings per share for 2020. As the economy rebounds, she reckons, profits will lag—in large part because of the changes in how companies and consumers spend when the crisis ends. With the unemployment rate surging to highs not seen since the Great Depression, families will be more cautious about spending on everything from restaurants to cars. Executives, having seen how productive their employees can be while working from home, will rethink the need for maintaining big, expensive offices. “That’s what our analysts are hearing from companies they cover, and what our private bankers are told by entrepreneurs running small businesses,” says Subramanian. The trend is likely to hammer rents and profits in commercial real estate.

Airlines will be slow to regain their pre-outbreak altitude, especially now that the entire business world has been conditioned to meet via Zoom. “Leisure travel will probably go back to normal,” says Subramanian. “But business travel will fall. Executives will reconsider the need to go to China four times, or Europe twice a year.”

Naturally, sectors catering to working and shopping from home will be big beneficiaries, and their gains will partly offset the damage. It’s happening right now. Microsoft’s Teams video collaboration service, for instance, has jumped from 44 million to 75 million daily active users since mid-March. Microsoft has also benefited from rising sales of its cloud services and networking technology for stay-at-home workers. The demand helped boost the software giant’s operating income 25% in the first quarter.

But a boost from digital winners won’t be sufficient to cover the broader-¬based weakness in profits—at least in the short term. The problem is margins. Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, predicts much lower profitability from the overseas sales that contributed over 40% of the S&P 500’s total revenue last year. China’s growth has slowed, he notes, and Europe and emerging markets are likely to rebound far more slowly than the U.S. A bigger pool of Americans looking for work will slow growth in labor costs, but not enough to counter the lower prices that businesses from airlines to restaurants to hotels will need to charge to lure back customers.

The bottom line

So where will earnings settle if GDP indeed returns to last year’s heights by the end of 2021? In the fourth quarter of 2019, operating margins clocked in at 11.4%. That’s almost three points higher than the median over the past decade. Let’s keep it simple, and project that profitability returns to slightly above average, at 9% of sales. In that scenario, the S&P 500 would earn 20% less than in 2019, when EPS hit $163. My estimate is profits will land at $130 by the end of 2021.

That outcome would be a big disappointment to Wall Street. The analysts surveyed by FactSet in May are projecting EPS for the S&P 500 of $168 a share in 2021, and the S&P poll says $165. But math and logic suggest both predictions are farfetched at best. Profits existed in a magical age until just a few months ago. It’s unlikely to return anytime soon.

A version of this article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline “The trillion-dollar question: How far will profits fall?”