美国人说“现金为王”是有道理的。

自从古代社会,人们的交换方式从以盐和牲畜进行物物交换变成使用商品货币以来,这种有价值的硬币和纸币便一直被沿用至今。美国在1776年尚未宣布独立之前,就开始发行货币,后来演变成了今天众所周知的美钞。

如今,现金仅次于借记卡,是美国第二种最常用的支付方式。但许多“无现金化”的支持者认为,美钞的时代即将结束。

随着公共卫生事件的爆发,使用现金引起了人们对于卫生和病毒传播问题的担忧,尽管事实证明纸钞的原料棉携带病毒颗粒的时间,与塑料信用卡和借记卡差不多,甚至更短。而且随着全球数字化的日益普及,各种各样的新技术不断涌现,让商品和服务支付变得更简单、更流畅。

近几年来现金的使用确实有所减少,但它不可能像无现金运动的支持者们所希望的那样彻底消失。费城、旧金山和纽约等多个城市最近都出台了法律,禁止商户仅接受银行卡支付和无接触支付。新泽西州在2019年通过了类似的法案,而马萨诸塞州从1978年就已经禁止商户只接受无现金支付。

专家们列出了许多理由,来证明将现金作为一种可行的支付方案的必要性。比如,无现金社会将把成百上千万无银行账户和缺少银行服务的美国人排除在外,其中大部分是有色人种;现金是最好的支付方式,能够保留一点点隐私;现金是许多文化习俗中不可分割的一部分,比如付小费和赠送礼物等;现金比数字支付更有弹性;最后,消费者的选择权是自由市场最重要的原则之一,而淘汰现金等于让消费者少了一种重要的支付方式。

美国消费者法律中心的副主管劳伦•桑德斯说:“无现金运动是危险的。”

无现金化不利于无银行账户的人群和有色人种社区

联邦存款保险公司的“2017年无银行账户与缺少银行服务家庭普查”显示,美国约6.5%的家庭(相当于1,410万成年人加上640万儿童)没有银行账户,这意味着这些家庭没有正规参保金融机构的账户。还有18.7%的美国家庭缺少银行服务,这意味着这些家庭虽然至少有一个参保金融机构的账户,但他们也在使用银行系统以外的金融产品或服务,例如工资日贷款或支票兑现服务等。

《消费者调查报告》的高级政策顾问克里斯蒂娜•泰特劳特表示:“顾名思义,任何无现金化的措施都会把这些群体排除在外。”

如果你有银行账户,支票兑现和免费转账都很方便。但没有银行账户的人通常必须使用支票兑现服务或者汇票,才能得到现金和进行转账,这些服务的收费很高。

彼得森国际经济研究所的研究员马丁•乔真帕说:“贫穷是昂贵的,而没有银行账户更是要承担极其高昂的代价。”

乔真帕称,美国银行业毫无必要地设置了较高的进入门槛。这导致低收入者(往往是有色人种,特别是黑人)只能游离在正规经济之外。一直以来,美国社会的各个方面都有排斥非白人的种族歧视历史,这种传统在银行业中也展现出丑陋的一面。

简而言之,美国银行系统绝不是为没有可支配收入的人服务的。所以,中低收入者使用银行系统的时候,受到的伤害要多过得到的帮助。例如,多数大银行规定支票账户和储蓄账户必须达到最低余额标准,才能避免产生手续费。泰特劳特说,这些手续费和透支费就是“没钱要交的费用。”

对穷人不利的银行收费还有ATM取款手续费、电汇转账费和借记卡刷卡费等,而且肯定不止这些。这些费用加起来是很大一笔支出。

《伯克利经济评论》的工作人员在一篇文章中写道:“多数透支费需要在三天内缴清,2014年透支费的中位数是34美元。但工资日贷款的年度百分利率在300%至600%之间;如果把透支手续费视为三天内偿还的工资日贷款,则年度百分利率高达1,700%。”

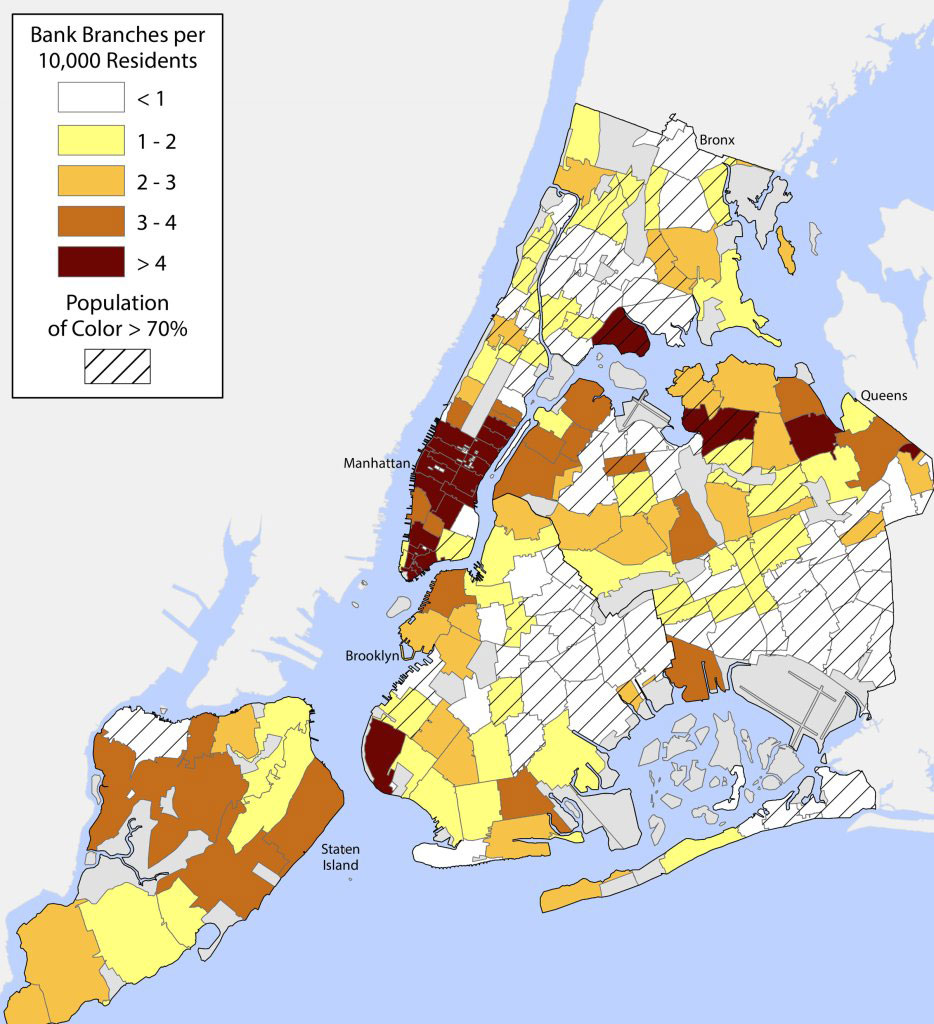

新经济项目的联合执行主任得伊阿尼拉•戴黎奥在今年1月前往美国众议院金融服务委员会金融科技工作组作证时表示,正规经济不利于低收入人群和有色人种的另外一种表现是银行网点的分布,在有色人种社区内,通常银行网点很少甚至根本没有银行。

例如,根据联邦存款保险公司以及2015年美国社区调查的数据编制的新经济地图显示,在纽约市的有色人种社区中,平均每1万名居民有一家银行。而在以白人为主的社区中,每1万名居民有3.5家银行。

泰特劳特说,高手续费、银行网点不足,以及其他令人烦恼的现象,比如当人们想要或者需要更小面额的时候,ATM机竟然只能取款20美元的钞票,这些因素导致许多人的经济状况不断恶化。这迫使人们放弃了银行账户和正规经济,选择了工资日贷款和支票兑现等非正规服务,因为这类服务的收费更低,更容易预测。她说,无银行账户的人大部分都有过账户,只是他们出于上述原因弃用了自己的账户。

美国公民自由联盟的高级政策分析师杰伊•斯坦利解释了数十年来对有色人种社区不利的“数字红线”现象。“数字红线”这种说法源自房地产市场拒绝向有色人种社区发放住房抵押贷款的“红线政策”。数字红线是指金融系统描绘有色人种客户(尤其是黑人)的许多做法。金融系统通过这种做法来排斥有色人种,或者给予他们不公平的待遇。

有钱人的钱能生钱,比如在银行账户中产生利息、在股票市场获得股息,以及累积信用卡奖励积分等。但随着通胀水平上升,无银行账户的人如果存款不增加,实际上就是在赔钱。这种负回报率最终会让没有银行账户的人的钱越来越少,经济状况日益恶化,更无法参与到正规的数字化经济当中。

泰特劳特指出:“人们之所以没有方便进行电子交易的银行账户,基本上是出于结构性的原因。”

诺桑比亚大学教授、金融技术与商业历史专家伯纳多•巴蒂兹-拉佐说,无现金运动要取得成功,并且避免过度损害无银行账户和缺少银行服务的人群的利益,就必须重新思考一直以来将这些人排除在外的银行系统。

戴黎奥在作证时表示:“关于金融准入差异的讨论往往集中在个人的选择和行为上,或者设计‘替代产品’的必要性上,它从未触及到阻碍穷人、移民和有色人种享受主流金融机构的服务和获取自由的结构性障碍。”

乔真帕表示,如果现金消失,无法使用最新金融技术付款的人将沦为二等公民。

支付系统历史专家和《电子价值交换:VISA电子支付系统的起源》(Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the VISA Electronic Payment System)一书的作者戴维•L•斯特恩斯说:“我想未来会出现严重的社会正义问题,它将成为全面实现‘无现金化’的障碍。”

纽约市在1月下旬通过了对商户的无现金禁令,市议会议员里奇•托里斯是该禁令的主要发起者。他说商户只接受无现金支付“虽然本意不是歧视,但实际上就是一种歧视行为。”但他补充说,店主知道哪些人倾向于现金支付,哪些人选择无现金支付,就可以控制其店铺的购物者,歧视行为就会变得更明显。

无现金社会侵犯隐私

在数字化的现代世界,人们每天都在失去越来越多的隐私——假如我们还有任何隐私的话。现金是目前最好的匿名支付方式,它对隐私的保护连加密货币也无法比拟。

斯特恩斯表示,人们想要匿名有许多原因,并非全都是出于不法目的。在金融领域,无论是秘密交易、免税付款,还是用夫妻共有的银行账户为配偶买礼物,保密都很重要。

斯坦利说,数据贩卖行业已经成了一个完整的产业链,他们对消费者财务记录中的数据垂涎不已。他认为,国会对于薄弱的隐私法律不闻不问,不进行修改,对数据库和金融服务公司能够与谁分享哪些信息,几乎没有任何限制。

斯坦利在为美国公民自由联盟发布的一篇博文中详细解释了公司如何从极少的信息中获取大量资料。消费者把信用卡交给卖家付款,卖家至少能获得消费者的全名。将客户的姓名与询问或猜测出(多数交易中都会有信用卡的注册邮编)的邮政编码相结合,所得出的信息之多让人震惊。卖家使用“数据附加”服务,可以通过客户的姓名和邮政编码获得客户的通信地址、电子邮件和手机号。卖家通过这些资料可以进入庞大的数据库,查询到更多信息。

根据1999年《金融服务现代化法案》,公司可以向任何人出售客户的财务数据。但在联邦法规下,消费者没有任何隐私可言,除非他们采取措施选择退出与可能掌握其信息的每一家公司的数据共享。

现金是消费者保持匿名的最后一种手段,使消费者可以真正保密其购买信息,避免大量数据落入公司手中让他们从中牟利,或者避免出现更糟糕的后果,被黑客盗取数据。

另外,尽管加密货币声称可以对用户的信息保密,但有许多种方法都能追溯到比特币的前主人。

现金扎根于我们的文化当中

当一位友善的女士把你的所有行李送到酒店房间的时候,如果你无法递给她五美元小费,你怎么办?假如在春节的时候,你无法用红包装着崭新的钞票送给孩子做礼物呢?

在谈论淘汰现金的好处时,我们忘掉了许多文化习俗。斯特恩斯说,从给小费到送礼物再到收藏,现金深深植根于我们的习俗当中。

在美国,人们用现金向提供服务的人支付小费,比如机场巴士的司机等,这并不是一种强制性交易。美国人还会教孩子金钱的知识和如何用现金做预算,每周用现金给孩子零花钱,对因为年龄太小而没有银行账户的孩子用现金作为对他们做家务等活动的奖励。

在印度南部的文化中,人们会举行kuri kalyanam派对,主人会在派对上筹款,而客人则会带来现金捐款。当主人获邀参加其他人的kuri kalyanam派对时,他们会捐出自己所收到的钱的两倍。

在希腊、墨西哥和波兰等国家的婚礼上,宾客会在新婚夫妇跳舞的时候,把钞票别在新人的衣服上。

斯特恩斯说,这些风俗的关键是有像现金这样的有价值的实物。如果现金消失,这些传统习俗也将不复存在。

当技术失灵的时候……

在最糟糕的情境下,假如互联网无法使用,我们该如何使用自己的钱?这种假设似乎有些牵强,但这是在制定法律和创建基础架构的时候必须考虑的一个重要问题。当技术失灵的时候,现金依旧存在。

巴蒂兹-拉佐说:“我们需要现金,因为我们必须有备用系统。”

他说,如今美国的经济活动都围绕着现金展开,现在确实需要重新思考消费者花钱的方式。但他认为现金的存在依旧重要,当技术无法正常运行时,现金就是“定海神针”。

斯坦利写道,电子支付系统的弹性无法与现金相比,它可能导致消费者面临集中故障点的影响。他在为美国公民自由联盟撰写的博文中写道:“如果因为黑客、官僚主义错误或自然灾害而导致消费者无法使用自己的账户,没有了现金就让他们没有选择。”

消费者选择权是关键

泰特劳特说:“消费者的支付选择权是关键。”

专家们认为未来不会进入无现金社会的一个关键原因是,无现金即使有再多的价值,也比不过被夺走的自由的价值。

提到现金使用,桑德斯说:“减少使用是一回事。淘汰现金是另一回事。”

她还提到了消费者选择支付联盟等团体。该联盟由消费者代表和企业组成,致力于维护消费者选择现金支付的权利。

旧金山联邦储备银行在2019年的“消费者支付选择日记”中明确表明,消费者重视现金这种支付方式的价值,虽然他们只是将现金作为数字支付的一种备用方式。该日记还显示,现金是小额交易的首选支付类型,10美元以下的交易接近一半是使用现金支付,25美元以下的交易使用现金支付的比例为42%。

虽然现金使用量每年都在逐步减少,但它依旧是美国人财务生活中的一种重要选择。

无现金化合法吗?

《美国法典》有关美国货币制度的一个章节中规定,“美国的硬币和纸币是所有债务、公共收费、税费和应付税款的法定货币。”这听起来是似乎任何地方都必须接受现金,对吗?事实上并非如此。

所有美国铸造的货币都是向债权人偿还债务的有效方式,但没有任何联邦法规规定私人企业、个人或机构必须接受用现金支付商品和服务的费用。

由于联邦政府和州政府负责管理政府服务,而且没有联邦法律强制接受现金,因此禁止无现金化的责任就落在了市立法者的身上。地方政府必须行动起来填补空缺,保护无银行账户人群和少数群体,因为他们尤其会被商户只接受无现金付款的行为影响。

纽约市禁止无现金化法案的主要发起者托里斯说:“我别无选择,只能推动针对这些边缘领域进行立法。”

纽约市的法案在2018年11月颁布以后,遭到了一些已经施行无现金化的商户、技术公司和信用卡公司(主要是万事达卡公司)的反对。他说,许多科技行业的从业者感觉抓住现金不放,对于真正的系统性问题来说只是权宜之计,是一种反科技的做法。

托里斯说禁止商户只接受无现金支付,并不会阻止技术的应用或进步,只是给人们提供了更多选择。他说他认为应该用法律解决导致许多人没有银行账户的诸多问题,但眼下必须通过禁止无现金化来保护无银行账户群体。

他预计:“人们会减少抗拒心理。”但他认为,在此之前,我们不能把金融技术强制应用到无银行账户和缺少银行服务的人群或者担心隐私问题的人身上。

进入无现金社会?早着呢!

虽然科技界有些人在大声疾呼,但现金肯定不会消失。

巴蒂兹-拉佐等专家认为,特殊时期将推动支付领域发生变化,但并不足以淘汰现金。他认为,这种变化会促使政府出台更强有力的法律,保护消费者的财务数据,重新评估万事达卡和Visa等大型金融技术公司所扮演的角色,甚至可能会拆分这些公司。

巴蒂兹-拉佐说:“希望有开明的人能记住,他们必须照顾到弱势消费者。”这样美国的金融系统将变得越来越好。

货币历史学家斯特恩斯说,无现金运动早在上世纪60年代末和70年代初就已经开始,经过了这么多年依旧没有成为主流。

泰特劳特说:“现金使用量的减少被夸大了。多年来一直有现金消失的说法,现在确实有许多人更多地使用电子支付,但我依旧认可现金为王的观点。”

有些专家认为当今美国经济的运行方式是“轻现金化”,即消费者有许多支付方式可供选择,并且多数人选择数字支付。但现金依旧是一种重要的支付方式,并将继续存在下去。

即使有令人兴奋的新技术诞生,人们依旧会回归现金支付。在公共事件爆发之初,有人担心使用现金可能会增加感染病毒的风险,但实际上人们对纸币的使用率与2019年秋季相同。

斯特恩斯说:“在付款方式这方面,我们是非常固执的。”

所以,尽管有人说无现金化代表了未来,但专家们认为这个未来不会太早来临。

正如斯坦利所说:“有时候,最古老、最简单的东西有其自身的价值,并且有理由继续存在下去。”(财富中文网)

译者:Biz

美国人说“现金为王”是有道理的。

自从古代社会,人们的交换方式从以盐和牲畜进行物物交换变成使用商品货币以来,这种有价值的硬币和纸币便一直被沿用至今。美国在1776年尚未宣布独立之前,就开始发行货币,后来演变成了今天众所周知的美钞。

如今,现金仅次于借记卡,是美国第二种最常用的支付方式。但许多“无现金化”的支持者认为,美钞的时代即将结束。

随着公共卫生事件的爆发,使用现金引起了人们对于卫生和病毒传播问题的担忧,尽管事实证明纸钞的原料棉携带病毒颗粒的时间,与塑料信用卡和借记卡差不多,甚至更短。而且随着全球数字化的日益普及,各种各样的新技术不断涌现,让商品和服务支付变得更简单、更流畅。

如今,现金仅次于借记卡,是美国第二种最常用的支付方式。但许多“无现金化”的支持者认为,美钞的时代即将结束。

近几年来现金的使用确实有所减少,但它不可能像无现金运动的支持者们所希望的那样彻底消失。费城、旧金山和纽约等多个城市最近都出台了法律,禁止商户仅接受银行卡支付和无接触支付。新泽西州在2019年通过了类似的法案,而马萨诸塞州从1978年就已经禁止商户只接受无现金支付。

专家们列出了许多理由,来证明将现金作为一种可行的支付方案的必要性。比如,无现金社会将把成百上千万无银行账户和缺少银行服务的美国人排除在外,其中大部分是有色人种;现金是最好的支付方式,能够保留一点点隐私;现金是许多文化习俗中不可分割的一部分,比如付小费和赠送礼物等;现金比数字支付更有弹性;最后,消费者的选择权是自由市场最重要的原则之一,而淘汰现金等于让消费者少了一种重要的支付方式。

美国消费者法律中心的副主管劳伦•桑德斯说:“无现金运动是危险的。”

无现金化不利于无银行账户的人群和有色人种社区

联邦存款保险公司的“2017年无银行账户与缺少银行服务家庭普查”显示,美国约6.5%的家庭(相当于1,410万成年人加上640万儿童)没有银行账户,这意味着这些家庭没有正规参保金融机构的账户。还有18.7%的美国家庭缺少银行服务,这意味着这些家庭虽然至少有一个参保金融机构的账户,但他们也在使用银行系统以外的金融产品或服务,例如工资日贷款或支票兑现服务等。

《消费者调查报告》的高级政策顾问克里斯蒂娜•泰特劳特表示:“顾名思义,任何无现金化的措施都会把这些群体排除在外。”

如果你有银行账户,支票兑现和免费转账都很方便。但没有银行账户的人通常必须使用支票兑现服务或者汇票,才能得到现金和进行转账,这些服务的收费很高。

彼得森国际经济研究所的研究员马丁•乔真帕说:“贫穷是昂贵的,而没有银行账户更是要承担极其高昂的代价。”

乔真帕称,美国银行业毫无必要地设置了较高的进入门槛。这导致低收入者(往往是有色人种,特别是黑人)只能游离在正规经济之外。一直以来,美国社会的各个方面都有排斥非白人的种族歧视历史,这种传统在银行业中也展现出丑陋的一面。

简而言之,美国银行系统绝不是为没有可支配收入的人服务的。所以,中低收入者使用银行系统的时候,受到的伤害要多过得到的帮助。例如,多数大银行规定支票账户和储蓄账户必须达到最低余额标准,才能避免产生手续费。泰特劳特说,这些手续费和透支费就是“没钱要交的费用。”

对穷人不利的银行收费还有ATM取款手续费、电汇转账费和借记卡刷卡费等,而且肯定不止这些。这些费用加起来是很大一笔支出。

《伯克利经济评论》的工作人员在一篇文章中写道:“多数透支费需要在三天内缴清,2014年透支费的中位数是34美元。但工资日贷款的年度百分利率在300%至600%之间;如果把透支手续费视为三天内偿还的工资日贷款,则年度百分利率高达1,700%。”

新经济项目的联合执行主任得伊阿尼拉•戴黎奥在今年1月前往美国众议院金融服务委员会金融科技工作组作证时表示,正规经济不利于低收入人群和有色人种的另外一种表现是银行网点的分布,在有色人种社区内,通常银行网点很少甚至根本没有银行。

例如,根据联邦存款保险公司以及2015年美国社区调查的数据编制的新经济地图显示,在纽约市的有色人种社区中,平均每1万名居民有一家银行。而在以白人为主的社区中,每1万名居民有3.5家银行。

泰特劳特说,高手续费、银行网点不足,以及其他令人烦恼的现象,比如当人们想要或者需要更小面额的时候,ATM机竟然只能取款20美元的钞票,这些因素导致许多人的经济状况不断恶化。这迫使人们放弃了银行账户和正规经济,选择了工资日贷款和支票兑现等非正规服务,因为这类服务的收费更低,更容易预测。她说,无银行账户的人大部分都有过账户,只是他们出于上述原因弃用了自己的账户。

美国公民自由联盟的高级政策分析师杰伊•斯坦利解释了数十年来对有色人种社区不利的“数字红线”现象。“数字红线”这种说法源自房地产市场拒绝向有色人种社区发放住房抵押贷款的“红线政策”。数字红线是指金融系统描绘有色人种客户(尤其是黑人)的许多做法。金融系统通过这种做法来排斥有色人种,或者给予他们不公平的待遇。

有钱人的钱能生钱,比如在银行账户中产生利息、在股票市场获得股息,以及累积信用卡奖励积分等。但随着通胀水平上升,无银行账户的人如果存款不增加,实际上就是在赔钱。这种负回报率最终会让没有银行账户的人的钱越来越少,经济状况日益恶化,更无法参与到正规的数字化经济当中。

泰特劳特指出:“人们之所以没有方便进行电子交易的银行账户,基本上是出于结构性的原因。”

诺桑比亚大学教授、金融技术与商业历史专家伯纳多•巴蒂兹-拉佐说,无现金运动要取得成功,并且避免过度损害无银行账户和缺少银行服务的人群的利益,就必须重新思考一直以来将这些人排除在外的银行系统。

戴黎奥在作证时表示:“关于金融准入差异的讨论往往集中在个人的选择和行为上,或者设计‘替代产品’的必要性上,它从未触及到阻碍穷人、移民和有色人种享受主流金融机构的服务和获取自由的结构性障碍。”

乔真帕表示,如果现金消失,无法使用最新金融技术付款的人将沦为二等公民。

支付系统历史专家和《电子价值交换:VISA电子支付系统的起源》(Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the VISA Electronic Payment System)一书的作者戴维•L•斯特恩斯说:“我想未来会出现严重的社会正义问题,它将成为全面实现‘无现金化’的障碍。”

纽约市在1月下旬通过了对商户的无现金禁令,市议会议员里奇•托里斯是该禁令的主要发起者。他说商户只接受无现金支付“虽然本意不是歧视,但实际上就是一种歧视行为。”但他补充说,店主知道哪些人倾向于现金支付,哪些人选择无现金支付,就可以控制其店铺的购物者,歧视行为就会变得更明显。

无现金社会侵犯隐私

在数字化的现代世界,人们每天都在失去越来越多的隐私——假如我们还有任何隐私的话。现金是目前最好的匿名支付方式,它对隐私的保护连加密货币也无法比拟。

斯特恩斯表示,人们想要匿名有许多原因,并非全都是出于不法目的。在金融领域,无论是秘密交易、免税付款,还是用夫妻共有的银行账户为配偶买礼物,保密都很重要。

斯坦利说,数据贩卖行业已经成了一个完整的产业链,他们对消费者财务记录中的数据垂涎不已。他认为,国会对于薄弱的隐私法律不闻不问,不进行修改,对数据库和金融服务公司能够与谁分享哪些信息,几乎没有任何限制。

斯坦利在为美国公民自由联盟发布的一篇博文中详细解释了公司如何从极少的信息中获取大量资料。消费者把信用卡交给卖家付款,卖家至少能获得消费者的全名。将客户的姓名与询问或猜测出(多数交易中都会有信用卡的注册邮编)的邮政编码相结合,所得出的信息之多让人震惊。卖家使用“数据附加”服务,可以通过客户的姓名和邮政编码获得客户的通信地址、电子邮件和手机号。卖家通过这些资料可以进入庞大的数据库,查询到更多信息。

根据1999年《金融服务现代化法案》,公司可以向任何人出售客户的财务数据。但在联邦法规下,消费者没有任何隐私可言,除非他们采取措施选择退出与可能掌握其信息的每一家公司的数据共享。

现金是消费者保持匿名的最后一种手段,使消费者可以真正保密其购买信息,避免大量数据落入公司手中让他们从中牟利,或者避免出现更糟糕的后果,被黑客盗取数据。

另外,尽管加密货币声称可以对用户的信息保密,但有许多种方法都能追溯到比特币的前主人。

现金扎根于我们的文化当中

当一位友善的女士把你的所有行李送到酒店房间的时候,如果你无法递给她五美元小费,你怎么办?假如在春节的时候,你无法用红包装着崭新的钞票送给孩子做礼物呢?

在谈论淘汰现金的好处时,我们忘掉了许多文化习俗。斯特恩斯说,从给小费到送礼物再到收藏,现金深深植根于我们的习俗当中。

在美国,人们用现金向提供服务的人支付小费,比如机场巴士的司机等,这并不是一种强制性交易。美国人还会教孩子金钱的知识和如何用现金做预算,每周用现金给孩子零花钱,对因为年龄太小而没有银行账户的孩子用现金作为对他们做家务等活动的奖励。

在印度南部的文化中,人们会举行kuri kalyanam派对,主人会在派对上筹款,而客人则会带来现金捐款。当主人获邀参加其他人的kuri kalyanam派对时,他们会捐出自己所收到的钱的两倍。

在希腊、墨西哥和波兰等国家的婚礼上,宾客会在新婚夫妇跳舞的时候,把钞票别在新人的衣服上。

斯特恩斯说,这些风俗的关键是有像现金这样的有价值的实物。如果现金消失,这些传统习俗也将不复存在。

当技术失灵的时候……

在最糟糕的情境下,假如互联网无法使用,我们该如何使用自己的钱?这种假设似乎有些牵强,但这是在制定法律和创建基础架构的时候必须考虑的一个重要问题。当技术失灵的时候,现金依旧存在。

巴蒂兹-拉佐说:“我们需要现金,因为我们必须有备用系统。”

他说,如今美国的经济活动都围绕着现金展开,现在确实需要重新思考消费者花钱的方式。但他认为现金的存在依旧重要,当技术无法正常运行时,现金就是“定海神针”。

斯坦利写道,电子支付系统的弹性无法与现金相比,它可能导致消费者面临集中故障点的影响。他在为美国公民自由联盟撰写的博文中写道:“如果因为黑客、官僚主义错误或自然灾害而导致消费者无法使用自己的账户,没有了现金就让他们没有选择。”

消费者选择权是关键

泰特劳特说:“消费者的支付选择权是关键。”

专家们认为未来不会进入无现金社会的一个关键原因是,无现金即使有再多的价值,也比不过被夺走的自由的价值。

提到现金使用,桑德斯说:“减少使用是一回事。淘汰现金是另一回事。”

她还提到了消费者选择支付联盟等团体。该联盟由消费者代表和企业组成,致力于维护消费者选择现金支付的权利。

旧金山联邦储备银行在2019年的“消费者支付选择日记”中明确表明,消费者重视现金这种支付方式的价值,虽然他们只是将现金作为数字支付的一种备用方式。该日记还显示,现金是小额交易的首选支付类型,10美元以下的交易接近一半是使用现金支付,25美元以下的交易使用现金支付的比例为42%。

虽然现金使用量每年都在逐步减少,但它依旧是美国人财务生活中的一种重要选择。

无现金化合法吗?

《美国法典》有关美国货币制度的一个章节中规定,“美国的硬币和纸币是所有债务、公共收费、税费和应付税款的法定货币。”这听起来是似乎任何地方都必须接受现金,对吗?事实上并非如此。

所有美国铸造的货币都是向债权人偿还债务的有效方式,但没有任何联邦法规规定私人企业、个人或机构必须接受用现金支付商品和服务的费用。

由于联邦政府和州政府负责管理政府服务,而且没有联邦法律强制接受现金,因此禁止无现金化的责任就落在了市立法者的身上。地方政府必须行动起来填补空缺,保护无银行账户人群和少数群体,因为他们尤其会被商户只接受无现金付款的行为影响。

纽约市禁止无现金化法案的主要发起者托里斯说:“我别无选择,只能推动针对这些边缘领域进行立法。”

纽约市的法案在2018年11月颁布以后,遭到了一些已经施行无现金化的商户、技术公司和信用卡公司(主要是万事达卡公司)的反对。他说,许多科技行业的从业者感觉抓住现金不放,对于真正的系统性问题来说只是权宜之计,是一种反科技的做法。

托里斯说禁止商户只接受无现金支付,并不会阻止技术的应用或进步,只是给人们提供了更多选择。他说他认为应该用法律解决导致许多人没有银行账户的诸多问题,但眼下必须通过禁止无现金化来保护无银行账户群体。

他预计:“人们会减少抗拒心理。”但他认为,在此之前,我们不能把金融技术强制应用到无银行账户和缺少银行服务的人群或者担心隐私问题的人身上。

进入无现金社会?早着呢!

虽然科技界有些人在大声疾呼,但现金肯定不会消失。

巴蒂兹-拉佐等专家认为,特殊时期将推动支付领域发生变化,但并不足以淘汰现金。他认为,这种变化会促使政府出台更强有力的法律,保护消费者的财务数据,重新评估万事达卡和Visa等大型金融技术公司所扮演的角色,甚至可能会拆分这些公司。

巴蒂兹-拉佐说:“希望有开明的人能记住,他们必须照顾到弱势消费者。”这样美国的金融系统将变得越来越好。

货币历史学家斯特恩斯说,无现金运动早在上世纪60年代末和70年代初就已经开始,经过了这么多年依旧没有成为主流。

泰特劳特说:“现金使用量的减少被夸大了。多年来一直有现金消失的说法,现在确实有许多人更多地使用电子支付,但我依旧认可现金为王的观点。”

有些专家认为当今美国经济的运行方式是“轻现金化”,即消费者有许多支付方式可供选择,并且多数人选择数字支付。但现金依旧是一种重要的支付方式,并将继续存在下去。

即使有令人兴奋的新技术诞生,人们依旧会回归现金支付。在公共事件爆发之初,有人担心使用现金可能会增加感染病毒的风险,但实际上人们对纸币的使用率与2019年秋季相同。

斯特恩斯说:“在付款方式这方面,我们是非常固执的。”

所以,尽管有人说无现金化代表了未来,但专家们认为这个未来不会太早来临。

正如斯坦利所说:“有时候,最古老、最简单的东西有其自身的价值,并且有理由继续存在下去。”(财富中文网)

译者:Biz

There’s a reason they say cash is king.

Commodity money—physical objects like coins and paper bills that hold value—has been used since ancient societies made the switch from bartering goods like salt and cattle. America started issuing its own currency, which evolved into the dollar we know today, in 1776, just before the country declared its independence.

Cash is still the second-most-used form of payment in America today after debit cards. But many advocates for “going cashless” believe that the paper dollar’s time is nearly up.

As the coronavirus pandemic ravages communities around the globe, the use of cash is raising concerns around cleanliness and viral transmission, even though the cotton that paper money is made of has been proved to carry virus particles for around the same time or less than plastic credit and debit cards do. And as digitization tightens its grip on the world, new technologies are popping up left and right to make paying for goods and services easier and more frictionless.

While its use has certainly declined in recent years, cash will likely never disappear as those in the cashless movement would hope. Many cities like Philadelphia, San Francisco, and New York have recently passed legislation banning merchants from accepting only card and contactless payments. New Jersey passed a similar bill in 2019 on the state level, and cashless merchants have been banned in Massachusetts since 1978.

There are many reasons experts list in arguing that cash must remain a viable payment option: Going cashless excludes the millions of unbanked and underbanked people in America, most of whom are people of color; cash is the best way to pay while maintaining a modicum of privacy; cash is integral to many cultural practices like tipping and gift giving; cash is resilient in a way that digital payments are not; and finally, consumer choice is one of the most important tenets of the free market, and eliminating cash removes one of the key payment options available to consumers.

“The cashless movement is a dangerous movement,” assistant director of the National Consumer Law Center Lauren Saunders says.

Going cashless disadvantages the unbanked and communities of color

Approximately 6.5% of U.S. households—14.1 million adults and 6.4 million children—are unbanked, according to the FDIC’s 2017 National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, meaning they live in a household holding no accounts with formal, insured financial institutions. Another 18.7% of households are underbanked, which means they have at least one account at an insured institution, but they also use financial products or services outside of the banking system, like payday loans or cash-checking services.

“Any move to cashlessness is, by definition, exclusionary to those groups,” Christina Tetreault, senior policy counsel at Consumer Reports, says.

If you have a bank account, it’s easy to get checks cashed and transfer money for free. But the unbanked typically have to use check-cashing services or money orders to get cash and transfer money, methods that cost quite a bit in fees.

“It’s expensive to be poor, and it’s very expensive to be unbanked,” says Martin Chorzempa, research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Banking in the United States has unnecessarily high barriers to entry, says Chorzempa. That leaves lower-income people—often people of color, particularly black people—from participating in the formal economy. America’s long and racist history of excluding nonwhite people in all corners of society rears its ugly head here too.

Simply put, the American banking system was not built for people without disposable income. So, when low- and middle-income people use these systems, they are often hurt more than helped. For instance, most major banks require checking and savings accounts to carry a minimum balance to avoid incurring fees. These and overdraft fees are simply “fees for not having money,” Tetreault says.

Other fees that disadvantage poorer people include but certainly aren’t limited to ATM withdrawal fees, wire transfer charges, and debit card swipe fees. Those add up.

“Most overdraft fees are repaid within three days, and the median fee in 2014 was $34,” reads an article by the Berkeley Economic Review staff. “However, the annual percentage rates for payday loans are between 300% and 600%; if overdraft fees were treated as a payday loan that is repaid within three days, the APR would be 1,700%.”

Another way lower-income people and people of color are disadvantaged in the formal economy is the physical placement of banks, which are often few and far between or entirely absent in communities of color, Deyanira Del Río, codirector of the New Economy project, said in her January testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services Task Force on Financial Technology.

For instance, in New York City neighborhoods of color, there is one bank on average per 10,000 residents, according to a New Economy map made by compiling data from the FDIC and the 2015 American Community Survey. In majority-white neighborhoods, there are 3.5 banks per 10,000 residents.

Mounting fees along with the banking deserts and irritations like ATMs dispensing only $20 bills when people may want or need to withdraw smaller amounts add up to a crippling financial situation for many, Tetreault says. That forces people to abandon their bank accounts and the formal economy in favor of the cheaper and easier-to-predict fees associated with informal services like payday loans and check-cashing. She says that most unbanked people used to have bank accounts, but chose to forgo them for these reasons.

Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the ACLU, explains that “digital redlining”—named after the redlining in the housing market that denied mortgages in neighborhoods of color—has worked against communities of colors for decades now. Digital redlining refers to a number of practices that profile customers of color (again, particularly black people) and excludes them from and disadvantages them in financial systems.

And while wealthier people’s money works for them—accruing interest in bank accounts, earning dividends in the stock market, and racking up rewards points with credit cards—the unbanked essentially lose money as inflation increases while their stockpile stays stagnant. This negative return rate ends up digging a deeper hole, leaving the unbanked with even less money, further from being able to participate in the formal, digitized economy if they want to.

“The reasons that people are shut out of bank accounts that would allow them to transact electronically are largely structural,” Tetreault says.

Bernardo Batiz-Lazo, a professor at Northumbria University and an expert in financial technology and business history, says for the cashless movement to succeed and not disproportionately disadvantage the unbanked and underbanked, the systems that work overtime to exclude those people must be rethought.

Del Río speaks of this in her testimony: “Too often, discussions about financial access disparities focus on the choices and behaviors of individuals, or on the need to design ‘alternative products,’ rather than on structural barriers that block poor people, immigrants, and people of color from mainstream financial institutions and freedom.”

Chorzempa says that if cash were to disappear, individuals without the access or means to pay for things with the newest financial technology effectively become second-class citizens.

“I think there’s going to be a big social justice question that would block the complete adoption of [cashlessness],” says David L. Stearns, an expert in the history of payment systems and author of Electronic Value Exchange: Origins of the VISA Electronic Payment System.

New York City Councilman Ritchie Torres, the prime sponsor of the ban on cashless merchants that the city passed in late January, says businesses going cashless is “discrimination not in intent, but in effect.” However, he adds, in knowing who tends to pay with cash and who could go cashless, business owners could control who shops at their stores, making the discrimination more overt.

A cashless society would surrender privacy

In the digital modern world, people lose more and more of their privacy every day—if there is any of it left at this point at all. Cash is the most anonymous form of payment that exists right now, preserving privacy in a way that even cryptocurrency doesn’t.

There are plenty of reasons, not all of them nefarious, to want anonymity in transactions, Stearns says. From under-the-table, taxless payments to buying a gift for a spouse with a joint bank account, privacy is a concern in the financial world.

There is an entire data-brokering industry that wants the data that comes from consumers’ financial records, Stanley says. And Congress, he believes, is allowing weak privacy laws to go unchecked and unchanged, placing few to no limits on what data banks and financial services companies can share and with whom.

In a blog post for the ACLU, Stanley detailed how companies can gain access to a wealth of knowledge from very little information. When given a credit card for payment, a seller can, at the very least, learn the consumer’s full name. That, with the customer’s zip code, either asked for or guessed (most transactions take place in a credit card’s registered zip code), can lead to a shocking amount of information. Using “data appending” services, the name and zip code can get that seller the consumer’s mailing address, email, and phone number. And with that knowledge, sellers can get into the giant databases and learn even more.

Under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, companies can sell customer financial data to just about anyone they choose. Consumers, then, have no privacy under federal regulations unless they take steps to opt out of that data-sharing with every company that might have their information.

Cash is one of the last strongholds left to maintain anonymity and keep purchasing information truly private without handing heaps of data to the corporations that make a buck off your receipts—or worse, to hackers, in the case of a data breach.

Despite cryptocurrency’s claim that it keeps users’ information private, there are plenty of ways to track the likes of Bitcoin back to their last owners.

Cash is ingrained in our cultures

What would you do if you couldn’t slide the kind woman that brings all your bags to your hotel room a five? If you couldn’t gift the kids in your life crisp new bills in a red envelope on Lunar New Year?

There are a lot of cultural customs we forget about when we discuss the merits of nixing cash. From tipping to gift giving to collecting, cash is deeply ingrained in our practices, Stearns says.

In the U.S., people use cash to tip people who perform services for which there isn’t a mandatory transaction, like an airport shuttle bus driver. Americans also teach their children about money and budgeting with cash, using it to pay weekly allowances and reward children who are too young for bank accounts for chores and the like. And don’t forget about the tooth fairy!

In Southern Indian culture, people throw kuri kalyanam parties, to which guests are expected to bring a cash donation for whatever big cost the host is raising funds for. When that host gets invited to someone else’s kuri kalyanam feast, they are expected to donate twice what they received at their party.

And at weddings in many cultures, including Greek, Mexican, and Polish, guests pin bills onto the happy couple’s clothing as they dance.

Having a physical object of value like cash is key to these practices, Stearns says. If cash dies, so too could these traditions.

Cash will be there when technology fails

In a doomsday scenario where we have no access to the Internet, how would we access our money? This may seem far-fetched, but it’s an important question to ask when creating laws and infrastructures. When technology fails, cash is there.

“We need to have cash because we need to have backup systems,” Batiz-Lazo says.

The economy as it is in America today was built for cash, he says, and it needs to be rethought for the way consumers use their money now. But cash is still important to keep around, he says, if only as an anchor for when technology doesn’t work according to plan.

Stanley writes that electronic payments systems are far less resilient than cash and leave consumers open to centralized points of failure. “If a hacker, bureaucratic error, or natural disaster shuts a consumer out of their account, the lack of a cash option would leave them few alternatives,” he writes for the ACLU.

Consumer choice is key

“Consumer payment choice is critical,” Tetreault says.

One of the key reasons that experts don’t see a cashless future is that the pros don’t outweigh the freedom that would be taken away.

“Minimizing is one thing,” Saunders says of cash use. “Eliminating it is something else.”

She also points to groups like the Consumer Choice Payment Coalition, a mix of consumer representatives and businesses committed to fighting for consumers’ right to choose cash.

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s 2019 Diary of Consumer Payment Choice makes clear that consumers value cash as an option, even if it’s mainly considered a backup to digital forms of payment. The diary also shows that cash is the preferred payment type for small transactions, used in nearly half of all transactions under $10, and 42% of those under $25.

While cash use is declining little by little each year, it remains an important option in the financial lives of Americans.

Is going cashless even legal?

A section of U.S. Code on the American monetary system states that “United States coins and currency are legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues.” That sure makes it sound like cash must be accepted everywhere, doesn’t it? Not so.

All U.S.-minted money is a valid form of payment for debts when tendered to a creditor, but there is no federal statute mandating that private businesses, individuals, or organizations have to accept cash as payment for goods and services.

Because federal and state governments can regulate government services, and there is no federal law mandating cash acceptance, it falls to city lawmakers to ban cashlessness. Local governments have to act to fill the voids and protect their unbanked and minority constituents that are disproportionately affected by cashless merchants.

“I have no choice but to legislate at the margins,” Torres, the prime sponsor of the bill banning cashlessness in New York City, says.

The New York bill was introduced in November 2018 and had plenty of pushback from already-cashless merchants, technology companies, and credit card companies, primarily Mastercard. Many in the tech industry, he says, feel that clinging to cash is a Band-Aid for real systemic problems and that it is an anti-tech move.

Torres says banning cashless merchants does nothing to prevent technology from being used or advanced—it just allows for more choice. And while he says he believes that there should be legislation to address the many issues causing people to go unbanked, this is what has to be done to protect that population for now.

“Then people would be less resistant,” he predicted. But until then, he says, we can’t force fintech on the unbanked and underbanked or those worried for their privacy.

Don’t expect America to go cashless anytime soon, if at all

Despite what some of the loudest voices in tech want you to think, cash probably isn’t going anywhere.

Some experts, like Batiz-Lazo, believe the pandemic will be a strong force for change in the payments landscape, but not one that eliminates cash. He believes that change will likely be a push for stronger legislation protecting consumer financial data and reassessing the role of—and maybe even breaking up—big fintech companies like Mastercard and Visa.

“If we just have some enlightened people that remember they have to take care of vulnerable consumers,” Batiz-Lazo says, the American financial system will get better for all involved.

The cashless movement, which money historian Stearns says started in the late ’60s and early ’70s, still hasn’t managed to go mainstream after all these years.

“The decline of cash is overstated,” Tetreault says. “There’s been a talk of the death of cash for many years, and it is true that many people make more electronic payments now, but I think cash is still king.”

The way the American economy functions these days is what some experts call “cash lite,” meaning that there are a lot of payment options for consumers to choose from, and most prefer the digital ones. But cash is still an important option to maintain.

Even as new and exciting financial technologies become available, people keep returning to cash. Despite fears at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic that cash might increase the risk of contracting the virus, people are using paper money at the same rate as they were in the fall of 2019.

“In the way we pay for things, we’re super stubborn,” Stearns says.

So though some say cashless is the future, the experts don’t see that future arriving anytime soon.

As Stanley says, “Sometimes the oldest, simplest things have their place and continue for a reason.”