新冠疫情像一根不断挥打的鞭子,美国数十个州和城市很有可能将感受到其新一轮鞭笞的威力,而政府则要应对财政收入的大规模突然损失。新冠疫情爆发后大范围的企业关停不仅仅是重创企业销售和拖累数千万工人薪资这么简单,它还在不断地削减这两个类目贡献的税收收入。

近期的预测显示,2021财年,仅销售和个人所得税的降低便会让州政府的财政收入减少1060亿美元至1250亿美元。然而,加州大学圣迭戈分校的经济学副教授杰弗瑞•克勒门斯称,如果计算州和地方其他财政收入来源受到的影响,整体缺口可能会轻易达到这个数额的两倍。克勒门斯于6月与美国企业研究所(American Enterprise Institute)的经济师斯坦•维格一道就该课题发表了一篇工作论文。

美国人口普查局(U.S. Census Bureau)现有的最近年份统计数据显示,美国50个州在2019财年的税收额超过了1万亿美元,这是美国税收额连续8年出现增长。有48个州称2019年的财政收入有所增长,而2018年有49个州。

总的来说,超过三分之二的财政收入来自于居民的个人所得税(约38%)以及普通销售税(31%),不过,这两类以及其他税收来源(包括企业所得税、不动产税和特种商品销售税,例如汽油、烟草或酒)可能会因地区不同出现巨大的差异。例如,在弗吉尼亚州,个人所得税占到了该州2019财年净财政收入的51.9%。与此同时,包括佛罗里达州、得克萨斯州和怀俄明州在内的7个州并不征收个人所得税。同样,不动产税占美国州财政总收入的比例不到2%,但却占到了佛蒙特州的约四分之一,而且这一比例每年都在增长。

尽管几乎上述所有的收入来源对经济下行十分敏感,个人所得税(受就业状况的影响十分明显)和普通销售税(反映了消费开支的实力)受疫情相关关停以及对公众聚集限令的影响尤为严重。

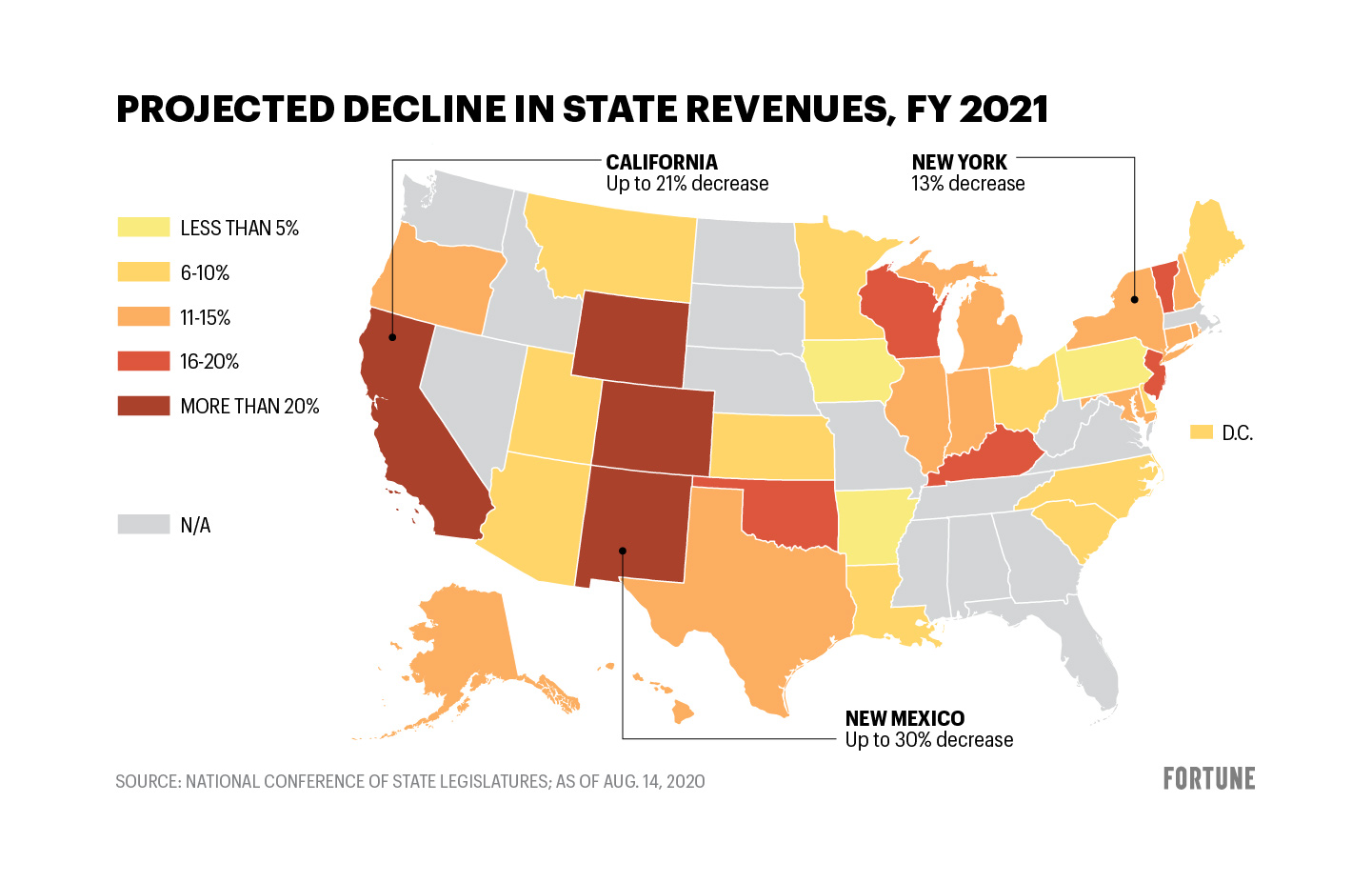

全美州议会联合会(National Conference of State Legislatures)统计的数据显示,这种经济领域的痛楚尤为剧烈和突然,在过去的5个月中,35个州与哥伦比亚特区发布了下调其2021财年财政收入的预测,至少有24个州将其预估财政收入较2019年削减了10%或更多。有7个州预计财政收入会下降15%或更多。这些修订基于对2020财年财政收入损失的判断,也就是企业关停开始之时。

新泽西州政府称,该州如今的缺口预计达到了100亿美元。加州在5月预测,该州将出现180亿美元的资金缺口,如果衰退和恢复最终呈现出“U型”(在今春短暂的暴跌之后出现短暂的恢复)。例如在“L型”恢复中,该州则会出现310亿美元的缺口。不过,这个数字还只是今夏灾难性、代价惨重的野火发生之前的估计。

阿拉斯加州无需担心个人所得税所导致的财政收入萎缩,因为它没有这个税种。然而,其财政亦受到了新冠疫情的强烈冲击。在最近的2019财年,阿拉斯加112亿美元的财政收入中有四分之一来自于石油特许费和相关税收。(阿拉斯加将其中的一些收费称之为“遣散税”,因为将油气从其土地中抽离。)然而在新冠疫情爆发后,该州的经济学家估计政府会出现数十亿美元的赤字,基本归咎于今春超低的油价。专家们称其起因源于“极度失衡的供需”,至少有一部分是受到了全球日趋严重的新冠疫情的影响。

该州悲观的财政前景基于37美元/桶的阿拉斯加North Slope原油。如今,价格较当时上涨了19%,可能也让该州的预算编制者多少松了口气。然而,该价格依然远低于年初70美元/桶的价格。

即便是严重依赖于个人所得和销售税的州也会定期从一系列收入来源中获得非税收入,例如属于“自有来源收入”类目的大学、医院、高速公路、机场、停车设施、停车场、公共设施和很多其他机构。人口普查局现有最近年份的数据显示,各州2017年的非税收入达到了3710亿美元。但各州如今的情况大致都差不多:其中大量的项目在经济关停中受到了波及,而且可能会再次因为新冠疫情的抬头而遭到冲击。

各大城市和市区每年的“自有来源”收入超过了一万亿美元,它们也有可能迎来预算噩梦。尽管这些资金的三分之二都来自于每年相对稳定的不动产税,但其余部分基本上都来自于销售税费,而后者像州财政一样受到了经济下行的影响。

克勒门斯说:“我认为最有可能出现的情况是,如果经济在未来的财年收缩10%,那么整个财政收入可能也会收缩10%左右。”2017年,州与地方自有来源收入共计达到了2.4万亿美元,也就是说各州和城市的整体财政收入将减少2400亿美元。

正因为如此,很多州府都在拼命地向华盛顿寻求援助。确实,众议院的民主党正在围绕新刺激方案与特朗普政府以及共和党主导的参议院打口水战,针对各州和城市的财政援助依然是一个重要的议题。如今,这两方似乎陷入了僵局。如果这个僵局持续下去,那么受影响最严重的州可能很快就会采取激进的举措。

与联邦政府不同的是,可以随意发债(而且证据表明它们也希望发债)州和地方政府在通过借贷这条路走出困境方面没有多少回旋的余地。克勒门斯说:“受预算平衡要求限制的大多数州都不允许使用长期债来资助普通资金开支。”

在没有联邦援助的情况下,等待州和城市工作人员的将是大量的裁员,而且新税种的出台几乎已成定局。不过,提振财政收入的各类可选措施都会带来严重的副作用,克勒门斯说:“提升销售税会在充分收入分配领域对家庭带来影响,而提升所得税可能会逼迫高收入人群离开该州。”

最后,最佳(从政治上最可行)方案可能是成本削减以及收入提振的双管齐下。克勒门斯说:“大多数这类问题的最佳解决方案都不是仅靠一种财务手段,而是分摊一些痛楚。避免出现超出必要的经济干扰的最佳办法涵盖当前州和地方政府雇员的工资冻结,当然像我这样的大学教职员工亦无法幸免。”(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

新冠疫情像一根不断挥打的鞭子,美国数十个州和城市很有可能将感受到其新一轮鞭笞的威力,而政府则要应对财政收入的大规模突然损失。新冠疫情爆发后大范围的企业关停不仅仅是重创企业销售和拖累数千万工人薪资这么简单,它还在不断地削减这两个类目贡献的税收收入。

2021财年各州财政收入预计降幅。来源:全美州议会联合会(截至2020年8月14日)

近期的预测显示,2021财年,仅销售和个人所得税的降低便会让州政府的财政收入减少1060亿美元至1250亿美元。然而,加州大学圣迭戈分校的经济学副教授杰弗瑞•克勒门斯称,如果计算州和地方其他财政收入来源受到的影响,整体缺口可能会轻易达到这个数额的两倍。克勒门斯于6月与美国企业研究所(American Enterprise Institute)的经济师斯坦•维格一道就该课题发表了一篇工作论文。

美国人口普查局(U.S. Census Bureau)现有的最近年份统计数据显示,美国50个州在2019财年的税收额超过了1万亿美元,这是美国税收额连续8年出现增长。有48个州称2019年的财政收入有所增长,而2018年有49个州。

总的来说,超过三分之二的财政收入来自于居民的个人所得税(约38%)以及普通销售税(31%),不过,这两类以及其他税收来源(包括企业所得税、不动产税和特种商品销售税,例如汽油、烟草或酒)可能会因地区不同出现巨大的差异。例如,在弗吉尼亚州,个人所得税占到了该州2019财年净财政收入的51.9%。与此同时,包括佛罗里达州、得克萨斯州和怀俄明州在内的7个州并不征收个人所得税。同样,不动产税占美国州财政总收入的比例不到2%,但却占到了佛蒙特州的约四分之一,而且这一比例每年都在增长。

尽管几乎上述所有的收入来源对经济下行十分敏感,个人所得税(受就业状况的影响十分明显)和普通销售税(反映了消费开支的实力)受疫情相关关停以及对公众聚集限令的影响尤为严重。

全美州议会联合会(National Conference of State Legislatures)统计的数据显示,这种经济领域的痛楚尤为剧烈和突然,在过去的5个月中,35个州与哥伦比亚特区发布了下调其2021财年财政收入的预测,至少有24个州将其预估财政收入较2019年削减了10%或更多。有7个州预计财政收入会下降15%或更多。这些修订基于对2020财年财政收入损失的判断,也就是企业关停开始之时。

新泽西州政府称,该州如今的缺口预计达到了100亿美元。加州在5月预测,该州将出现180亿美元的资金缺口,如果衰退和恢复最终呈现出“U型”(在今春短暂的暴跌之后出现短暂的恢复)。例如在“L型”恢复中,该州则会出现310亿美元的缺口。不过,这个数字还只是今夏灾难性、代价惨重的野火发生之前的估计。

阿拉斯加州无需担心个人所得税所导致的财政收入萎缩,因为它没有这个税种。然而,其财政亦受到了新冠疫情的强烈冲击。在最近的2019财年,阿拉斯加112亿美元的财政收入中有四分之一来自于石油特许费和相关税收。(阿拉斯加将其中的一些收费称之为“遣散税”,因为将油气从其土地中抽离。)然而在新冠疫情爆发后,该州的经济学家估计政府会出现数十亿美元的赤字,基本归咎于今春超低的油价。专家们称其起因源于“极度失衡的供需”,至少有一部分是受到了全球日趋严重的新冠疫情的影响。

该州悲观的财政前景基于37美元/桶的阿拉斯加North Slope原油。如今,价格较当时上涨了19%,可能也让该州的预算编制者多少松了口气。然而,该价格依然远低于年初70美元/桶的价格。

即便是严重依赖于个人所得和销售税的州也会定期从一系列收入来源中获得非税收入,例如属于“自有来源收入”类目的大学、医院、高速公路、机场、停车设施、停车场、公共设施和很多其他机构。人口普查局现有最近年份的数据显示,各州2017年的非税收入达到了3710亿美元。但各州如今的情况大致都差不多:其中大量的项目在经济关停中受到了波及,而且可能会再次因为新冠疫情的抬头而遭到冲击。

各大城市和市区每年的“自有来源”收入超过了一万亿美元,它们也有可能迎来预算噩梦。尽管这些资金的三分之二都来自于每年相对稳定的不动产税,但其余部分基本上都来自于销售税费,而后者像州财政一样受到了经济下行的影响。

克勒门斯说:“我认为最有可能出现的情况是,如果经济在未来的财年收缩10%,那么整个财政收入可能也会收缩10%左右。”2017年,州与地方自有来源收入共计达到了2.4万亿美元,也就是说各州和城市的整体财政收入将减少2400亿美元。

正因为如此,很多州府都在拼命地向华盛顿寻求援助。确实,众议院的民主党正在围绕新刺激方案与特朗普政府以及共和党主导的参议院打口水战,针对各州和城市的财政援助依然是一个重要的议题。如今,这两方似乎陷入了僵局。如果这个僵局持续下去,那么受影响最严重的州可能很快就会采取激进的举措。

与联邦政府不同的是,可以随意发债(而且证据表明它们也希望发债)州和地方政府在通过借贷这条路走出困境方面没有多少回旋的余地。克勒门斯说:“受预算平衡要求限制的大多数州都不允许使用长期债来资助普通资金开支。”

在没有联邦援助的情况下,等待州和城市工作人员的将是大量的裁员,而且新税种的出台几乎已成定局。不过,提振财政收入的各类可选措施都会带来严重的副作用,克勒门斯说:“提升销售税会在充分收入分配领域对家庭带来影响,而提升所得税可能会逼迫高收入人群离开该州。”

最后,最佳(从政治上最可行)方案可能是成本削减以及收入提振的双管齐下。克勒门斯说:“大多数这类问题的最佳解决方案都不是仅靠一种财务手段,而是分摊一些痛楚。避免出现超出必要的经济干扰的最佳办法涵盖当前州和地方政府雇员的工资冻结,当然像我这样的大学教职员工亦无法幸免。”(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

The coronavirus pandemic is the scourge that keeps on whipping—and its latest punishment is likely to be felt in dozens of states and municipalities across the United States as governments reckon with a massive and sudden loss of revenue. The widespread shutdown of businesses in the wake of COVID-19 didn’t just hammer sales from those businesses, along with the salaries of millions of workers, it’s also continuing to reduce the bounty that comes from taxing both of those sources of income.

Lower tax hauls from sales and personal income alone, according to recent projections, could cost state governments anywhere from $106 billion to $125 billion in fiscal year 2021, which began on July 1 in 46 states. The overall shortfall, however, could easily reach twice that amount when hits to other sources of state and local funds are factored in, says Jeffrey Clemens, an associate professor of economics at the University of California, San Diego, who published a working paper on the issue in June with Stan Veuger, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute.

The 50 states collected more than a trillion dollars in taxes in FY2019, the most recent year for which the U.S. Census Bureau has summary data. It was the eighth consecutive year state tax receipts had risen. Forty-eight states that year reported a bump in revenue, compared with 49 the year before.

Overall, more than two-thirds of that treasure derives from taxes on residents’ personal income (around 38%) as well as from general sales taxes (31%)—though the share from these and other sources (including taxes on corporate income, property, and sales of specific items such as gasoline, cigarettes, or alcohol) can differ dramatically from place to place. In Virginia, for instance, personal income taxes accounted for 51.9% of the commonwealth’s total net revenue collections in FY2019. Seven states, meanwhile—including Florida, Texas, and Wyoming—don’t levy a personal income tax at all. In the same vein, property taxes account for less than 2% of state revenues nationwide, but comprise roughly a quarter of the revenue Vermont raises each year.

While nearly all of these funding sources are vulnerable to economic downturns, personal income (which is clearly influenced by employment status) and general sales (which reflect the strength of consumer spending) have been particularly hit by the pandemic-related closures and restrictions on public gatherings.

The economic pain has been so sharp and swift that, over the past five months, 35 states plus the District of Columbia have released projections revising their FY2021 revenue downward—with at least 24 of those states slicing revenue estimates by 10% or more from pre-COVID forecasts, according to data gathered by the National Conference of State Legislatures. Seven states expect revenues to be down 15% or more. These revisions come on top of revenue losses in FY2020, when the shuttering of businesses began.

New Jersey now expects to be $10 billion in the hole, the state says. California predicted in May that state coffers would have an $18 billion shortfall—if the recession and recovery ended up looking like a “U” (with a brisk comeback following the equally brisk collapse this spring). An “L-shaped” recovery, for that matter, would leave it $31 billion underwater. That assessment, notably, came before this summer’s catastrophic and costly wildfires.

Alaska doesn’t have to worry about shrinking revenues from the personal income tax—it doesn’t have one. But its coffers are nonetheless getting thumped by the coronavirus. As recently as FY2019, the state got roughly a quarter of its $11.2 billion in revenue from petroleum royalties and related taxes. (Alaska calls some of these levies “severance taxes,” to account for the oil and gas that’s being severed from its land.) In the wake of COVID-19, however, state economists estimated a billion-dollar deficit, largely based on extremely low oil prices this spring—a crash they blamed on an “extreme supply and demand imbalance” caused at least in part by a global growth-killing pandemic.

The state’s dire fiscal outlook was based on a $37-a-barrel price for Alaska North Slope crude, and the price is up about 19% since then—so state budgeteers might be a little more sanguine these days. But it’s still way down from its $70 perch at the start of the year.

Even states that rely heavily on personal income and sales taxes routinely draw non-tax dollars from a litany of sources: universities, hospitals, highways, airports, parking facilities, parks, utilities, and a slew of other things that also fall under the heading of “own-source revenue.” States received $371 billion in these non-tax fees in 2017, the latest year available from the Census Bureau. But the story is largely the same here: Lots of these line items were bludgeoned in the economic shutdown and may get hit again if COVID-19 infections surge anew.

Cities and municipalities, which receive more than a trillion dollars in their own “own-source” revenue each year, are likewise facing budgetary nightmares. While two-thirds of those funds come from property taxes, which are relatively stable from year to year, the rest—which largely hails from sales taxes and fees—is just as affected by an economic downturn as the state revenue.

“My best guess would be that, if the economy is going to be 10% smaller over this coming fiscal year, then the whole of these revenues will probably be about 10% smaller,” says Clemens. In 2017, state and local own-source revenue totaled $2.4 trillion. That translates to a $240 billion gut-punch to states and cities.

And that has many state capitals desperately looking to Washington for help. Indeed, as Democrats in the House wrangle with the Trump administration and the Republican-led Senate over a new stimulus plan, financial assistance for states and cities remains a key sticking point. For now, the two sides appear to be at an impasse. If the stalemate continues, the hardest-hit states may have to start taking aggressive measures very soon.

Unlike the federal government, which can issue as much debt as it wants (and it has shown that it wants), state and local governments have much less leeway to borrow their way out of the ditch. “Most states, which face balanced-budget requirements, are not allowed to use long-term debt to finance general fund expenditures,” says Clemens.

Without federal aid, state and city workers will face significant layoffs, and there is almost certain to be a push for new taxes too. But all the various options on the revenue-raising side come with serious downsides, Clemens says: “Increasing taxes on sales affects families across the full-income distribution; raising income taxes risks chasing higher-income folks out of the state.”

In the end, the best (and most politically acceptable) option is likely to be a combination of cost-cutting and revenue-raising measures. “Most problems of this kind are best solved by not going all-in on any one financial lever, but rather by spreading some of the pain around,” says Clemens. “The best options for avoiding more-than-necessary economic disruption would be things like wage freezes of current state and local government employees—which, of course, includes, university faculty like myself.”