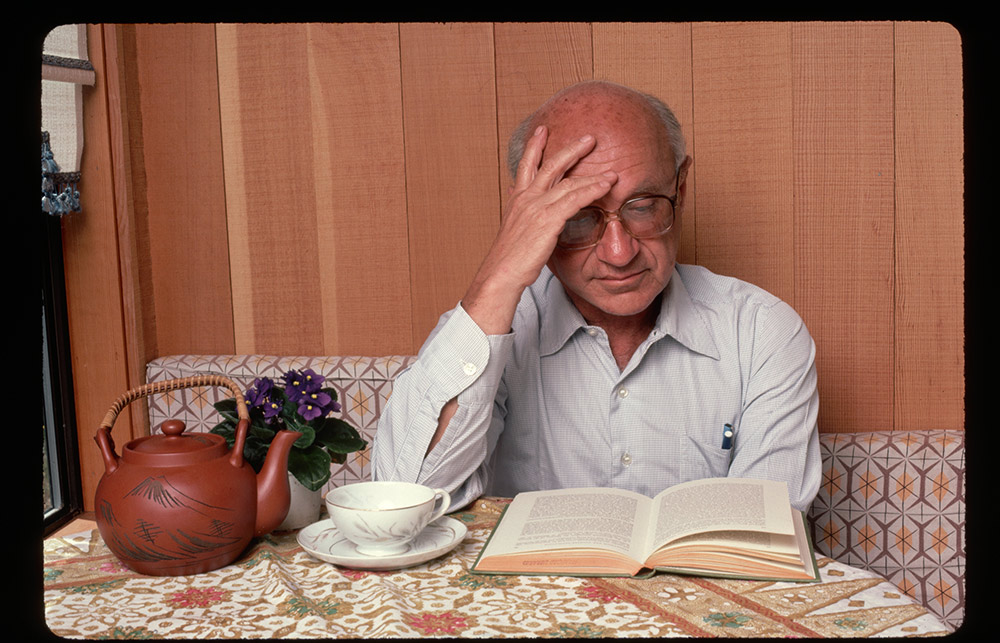

50年前,米尔顿•弗里德曼在《纽约时报》杂志上宣称,企业的社会责任就是实现利润增长。董事的责任是维护主人即股东的利益,赚取尽可能多的利润。弗里德曼反对罗斯福新政和欧洲的社会民主模式,并敦促企业界尽量降低工会的效率,减少应对环境和消费者保护措施的努力,削弱反垄断法。他希望公司董事会降低对人的关注,削弱法律上制定的企业公平对待工人、消费者和社会的要求。

过去50年里,弗里德曼的观点在美国影响力越来越大。结果是,股票市场和富裕精英的权力飙升,对工人、环境和消费者利益的关注减少,导致经济上出现严重的不稳定和不平等,对气候变化应对迟缓,公共机构也受到破坏。公司利用财富和实力追求利润,率先放松了能够防止工人和其他利益相关者受过度行为影响的外部约束。

在弗里德曼范式的主导下,公司不断受到股东决议、收购和对冲基金激进主义等机制的困扰,过于狭隘地关注股东回报。在机构投资者的推动下,高管薪酬体系日渐注重股票总回报率。企业变成股票市场的玩物,越发难以按照开明的方式运作,很难反映人类投资者在可持续增长、公平对待工人和保护环境方面的实际利益。

半个世纪后,很明显,如此狭隘、以股东为中心的企业观对社会造成了严重影响。早在新冠肺炎疫情爆发之前,有人就曾经批评企业过分关注利润,导致自然和生物多样性退化,纵容全球变暖、工资停滞不前,也使得经济不平等加剧。最明显的例子就是员工与企业精英利益分配严重不均,股东和高管层攫取了蛋糕的大部分。

如今,美国企业界意识到了此类思维方式对社会契约的威胁。作为回应,2019年商业圆桌会议(Business Roundtable)发布企业使命声明,强调对利益相关者和股东的责任。然而在疫情期间,多家签署企业并未遵照承诺保护利益相关者,于是人们对签署该文件的初衷以及后续行动持怀疑态度。

股东权益倡导者声称企业使命声明收效甚微,确实没错。要求企业高管只对强大的群体,即以高度强势的机构投资者形式存在的股东负责,而对其他利益相关者不承担法律责任,还要以公平方式管理公司,对利益相关者来说不仅无效,而且很幼稚,逻辑也不清晰。

我们需要的是,确保企业承诺履行与其影响力相配的社会责任。实际上,这点一直存在缺位。美国的公司法规定,董事和经理应该受制于强大的股东权力,以权衡其他利益相关者的利益。原则上说,公司可以追求超出利润和利益相关者的使命,但前提是获得强大投资者的批准。归根结底,由于法律要求相当宽泛,企业在公平对待所有利益相关者方面受到了严格限制,因为控制权都已经移交给投资者和金融市场。

由于缺乏有效鼓励遵守圆桌会议声明的机制,系统对实际遵守的企业并不利。公司不需要照顾利益相关者,多数情况下也确实没有,因为这么做会让股东愤怒。去年,机构投资者委员会(Council of Institutional Investors)对圆桌会议宣言的下意识反应就说明了这点。委员会表示反对,称圆桌会议并未承认股东既是资本所有者,也是资本提供者,而“对所有人负责意味着对任何人都不负责”。

如果圆桌会议真要从股东至上转向追求使命,需要做两件事。一是罗斯福新政中的承诺要更新,对美国工人、环境和消费者保护更接近德国及斯堪的纳维亚诸国制定的标准。

但要想实现第一件事,第二件事必不可少。公司法本身必须调整,以便企业更好地恢复相关框架,内部管理更加尊重工人和社会。改变公司法的权力结构,要求企业公平考虑利益相关者,克制利润高于其他价值的欲望,也可以防止公司弱化保护工人、消费者和社会的相关规定。

为了实现这一转变,公司使命要确立为公司法的核心,以表现出公司更广泛的社会责任以及董事保障施行的职责。根据美国多个州的法律,企业可通过授权公益法人(PBC)来实现。公益法人有责任声明企业除利润以外的公共使命,将实现使命作为董事的职责,还要承担履行的责任。该模式与一些州的利益相关者规定明显存在区别,因为有些州希望强化利益相关者的利益,但利益相关者主张将其无效。公益法人变成优秀企业公民的明确义务,要尊重所有利益相关者。类似要求具有强制性,而利益相关者规定则比较模糊。

公益法人的重要性日渐提升,很多年轻的创业者也已经接受,他们认为所有人都能够公平赚钱才是负责任的前进之路。不过该模式最终成功与否取决于长期应用模式的企业。

即使在圆桌会议高调发表声明之后,大规模转变并未发生,而且理由很充分。虽然企业可以选择成为公益法人,但并无义务,而且需要股东支持。对于创始人掌控的公司或股东人数相对较少的公司来说,如果各方均强烈倾向公益法人形式就相对容易。而要获得分散的机构投资者批准则困难得多,机构投资者要对更分散的个人投资者群体负责。当前企业若想实现改革,协调是个大问题。

所以法律需要调整。公益法人不应该成为股东至上之外的选择,而应该成为社会重要公司的普遍标准。至于社会重要公司的标准,参议员伊丽莎白•沃伦提出的建议是收入超过10亿美元。在美国,企业根据各州法律转为公益法人效率最高。美国制度的魔力在很大程度上取决于联邦政府与各州之间的合作,实现国家标准和灵活执行的最佳结合。该方法也正是基于此。

按照美国法律,公司股东和董事享有实质性的优势和保护,但并不能够延伸到经营者。在提供各项权利后,社会可以合理地期望从公司行为中获益,而非遭受损失。在公司法中要将社会责任定为义务,可以恢复公司的合法性。

该制度有三项核心。首先,企业必须是负责任的企业公民,公平对待员工和其他利益相关者,避免出现碳排放等可能对他人造成不合理或不相称伤害的外部因素。第二,企业应该通过造福他人来谋取利润。第三,要测定和报告业绩证明达到了两项标准。

公益法人模式包含了三项要素,而且背后有法律力量和市场力量。公司经理和大多数人一样要认真对待义务。如果做不到,在公益法人模式下,允许法院发布禁止令等指示,要求公司履行对利益相关者和社会的义务。此外,公益法人模式要求在企业生命周期的各个阶段公平对待所有利益相关者,即使要出售也应如此。该模式将权力转交给对社会负责的投资和指数基金,相关基金专注于长期发展,无法从危害社会的不可持续增长方式中获益。

我们建议修改公司法以确保负责任的企业公民身份,很可能将引发既得利益者和传统学术界人士的强烈抗议。他们会声称这条路行不通,对创业和创新将造成毁灭性打击,破坏推动增长和繁荣的资本主义制度,对全球各地就业、养老金和投资造成威胁。如果把企业使命作为公司法核心有如此大的破坏力,人们可能会怀疑当初为何要发明公司。

很显然,结果与某些威胁是相反的。将使命纳入法律,遵照法律要求实现创建企业的初心,只会简化企业经营而不是将其复杂化。该模式将成为企业家精神、创新和灵感的源泉,为个人、社会和自然面临的问题找到解决方案。通过鼓励对福利和繁荣作出积极贡献,而不是以牺牲他人为代价转移财富,市场和资本主义制度可以更好地发挥作用。此外,该模式还能够创造有意义且令人满意的工作,支持员工就业并保障退休,鼓励可以为全民创造财富的投资。

我们呼吁大企业普遍采用公益法人模式。这样才能够避免资本主义制度和企业面临当前做法的破坏性后果,而这也是为了下一代,为了社会和大自然。(财富中文网)

科林•迈耶是牛津大学萨伊德商学院的彼得•摩尔管理学教授,也是英国社会科学院未来企业项目的学术带头人。

小利奥•E•斯特林是宾夕法尼亚大学凯里法学院的迈克尔•L•瓦赫特法律和政策杰出研究员、哥伦比亚大学法学院艾拉•M•米尔斯坦全球市场和企业所有权中心的杰出高级研究员、特拉华州前首席大法官和校长,也在Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, & Katz律师事务所担任法律顾问。

雅普•温特是Phyleon Leadership and Governance的合伙人,在阿姆斯特丹自由大学担任公司法、治理和行为学教授。

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

50年前,米尔顿•弗里德曼在《纽约时报》杂志上宣称,企业的社会责任就是实现利润增长。董事的责任是维护主人即股东的利益,赚取尽可能多的利润。弗里德曼反对罗斯福新政和欧洲的社会民主模式,并敦促企业界尽量降低工会的效率,减少应对环境和消费者保护措施的努力,削弱反垄断法。他希望公司董事会降低对人的关注,削弱法律上制定的企业公平对待工人、消费者和社会的要求。

过去50年里,弗里德曼的观点在美国影响力越来越大。结果是,股票市场和富裕精英的权力飙升,对工人、环境和消费者利益的关注减少,导致经济上出现严重的不稳定和不平等,对气候变化应对迟缓,公共机构也受到破坏。公司利用财富和实力追求利润,率先放松了能够防止工人和其他利益相关者受过度行为影响的外部约束。

在弗里德曼范式的主导下,公司不断受到股东决议、收购和对冲基金激进主义等机制的困扰,过于狭隘地关注股东回报。在机构投资者的推动下,高管薪酬体系日渐注重股票总回报率。企业变成股票市场的玩物,越发难以按照开明的方式运作,很难反映人类投资者在可持续增长、公平对待工人和保护环境方面的实际利益。

半个世纪后,很明显,如此狭隘、以股东为中心的企业观对社会造成了严重影响。早在新冠肺炎疫情爆发之前,有人就曾经批评企业过分关注利润,导致自然和生物多样性退化,纵容全球变暖、工资停滞不前,也使得经济不平等加剧。最明显的例子就是员工与企业精英利益分配严重不均,股东和高管层攫取了蛋糕的大部分。

如今,美国企业界意识到了此类思维方式对社会契约的威胁。作为回应,2019年商业圆桌会议(Business Roundtable)发布企业使命声明,强调对利益相关者和股东的责任。然而在疫情期间,多家签署企业并未遵照承诺保护利益相关者,于是人们对签署该文件的初衷以及后续行动持怀疑态度。

股东权益倡导者声称企业使命声明收效甚微,确实没错。要求企业高管只对强大的群体,即以高度强势的机构投资者形式存在的股东负责,而对其他利益相关者不承担法律责任,还要以公平方式管理公司,对利益相关者来说不仅无效,而且很幼稚,逻辑也不清晰。

我们需要的是,确保企业承诺履行与其影响力相配的社会责任。实际上,这点一直存在缺位。美国的公司法规定,董事和经理应该受制于强大的股东权力,以权衡其他利益相关者的利益。原则上说,公司可以追求超出利润和利益相关者的使命,但前提是获得强大投资者的批准。归根结底,由于法律要求相当宽泛,企业在公平对待所有利益相关者方面受到了严格限制,因为控制权都已经移交给投资者和金融市场。

由于缺乏有效鼓励遵守圆桌会议声明的机制,系统对实际遵守的企业并不利。公司不需要照顾利益相关者,多数情况下也确实没有,因为这么做会让股东愤怒。去年,机构投资者委员会(Council of Institutional Investors)对圆桌会议宣言的下意识反应就说明了这点。委员会表示反对,称圆桌会议并未承认股东既是资本所有者,也是资本提供者,而“对所有人负责意味着对任何人都不负责”。

如果圆桌会议真要从股东至上转向追求使命,需要做两件事。一是罗斯福新政中的承诺要更新,对美国工人、环境和消费者保护更接近德国及斯堪的纳维亚诸国制定的标准。

但要想实现第一件事,第二件事必不可少。公司法本身必须调整,以便企业更好地恢复相关框架,内部管理更加尊重工人和社会。改变公司法的权力结构,要求企业公平考虑利益相关者,克制利润高于其他价值的欲望,也可以防止公司弱化保护工人、消费者和社会的相关规定。

为了实现这一转变,公司使命要确立为公司法的核心,以表现出公司更广泛的社会责任以及董事保障施行的职责。根据美国多个州的法律,企业可通过授权公益法人(PBC)来实现。公益法人有责任声明企业除利润以外的公共使命,将实现使命作为董事的职责,还要承担履行的责任。该模式与一些州的利益相关者规定明显存在区别,因为有些州希望强化利益相关者的利益,但利益相关者主张将其无效。公益法人变成优秀企业公民的明确义务,要尊重所有利益相关者。类似要求具有强制性,而利益相关者规定则比较模糊。

公益法人的重要性日渐提升,很多年轻的创业者也已经接受,他们认为所有人都能够公平赚钱才是负责任的前进之路。不过该模式最终成功与否取决于长期应用模式的企业。

即使在圆桌会议高调发表声明之后,大规模转变并未发生,而且理由很充分。虽然企业可以选择成为公益法人,但并无义务,而且需要股东支持。对于创始人掌控的公司或股东人数相对较少的公司来说,如果各方均强烈倾向公益法人形式就相对容易。而要获得分散的机构投资者批准则困难得多,机构投资者要对更分散的个人投资者群体负责。当前企业若想实现改革,协调是个大问题。

所以法律需要调整。公益法人不应该成为股东至上之外的选择,而应该成为社会重要公司的普遍标准。至于社会重要公司的标准,参议员伊丽莎白•沃伦提出的建议是收入超过10亿美元。在美国,企业根据各州法律转为公益法人效率最高。美国制度的魔力在很大程度上取决于联邦政府与各州之间的合作,实现国家标准和灵活执行的最佳结合。该方法也正是基于此。

按照美国法律,公司股东和董事享有实质性的优势和保护,但并不能够延伸到经营者。在提供各项权利后,社会可以合理地期望从公司行为中获益,而非遭受损失。在公司法中要将社会责任定为义务,可以恢复公司的合法性。

该制度有三项核心。首先,企业必须是负责任的企业公民,公平对待员工和其他利益相关者,避免出现碳排放等可能对他人造成不合理或不相称伤害的外部因素。第二,企业应该通过造福他人来谋取利润。第三,要测定和报告业绩证明达到了两项标准。

公益法人模式包含了三项要素,而且背后有法律力量和市场力量。公司经理和大多数人一样要认真对待义务。如果做不到,在公益法人模式下,允许法院发布禁止令等指示,要求公司履行对利益相关者和社会的义务。此外,公益法人模式要求在企业生命周期的各个阶段公平对待所有利益相关者,即使要出售也应如此。该模式将权力转交给对社会负责的投资和指数基金,相关基金专注于长期发展,无法从危害社会的不可持续增长方式中获益。

我们建议修改公司法以确保负责任的企业公民身份,很可能将引发既得利益者和传统学术界人士的强烈抗议。他们会声称这条路行不通,对创业和创新将造成毁灭性打击,破坏推动增长和繁荣的资本主义制度,对全球各地就业、养老金和投资造成威胁。如果把企业使命作为公司法核心有如此大的破坏力,人们可能会怀疑当初为何要发明公司。

很显然,结果与某些威胁是相反的。将使命纳入法律,遵照法律要求实现创建企业的初心,只会简化企业经营而不是将其复杂化。该模式将成为企业家精神、创新和灵感的源泉,为个人、社会和自然面临的问题找到解决方案。通过鼓励对福利和繁荣作出积极贡献,而不是以牺牲他人为代价转移财富,市场和资本主义制度可以更好地发挥作用。此外,该模式还能够创造有意义且令人满意的工作,支持员工就业并保障退休,鼓励可以为全民创造财富的投资。

我们呼吁大企业普遍采用公益法人模式。这样才能够避免资本主义制度和企业面临当前做法的破坏性后果,而这也是为了下一代,为了社会和大自然。(财富中文网)

科林•迈耶是牛津大学萨伊德商学院的彼得•摩尔管理学教授,也是英国社会科学院未来企业项目的学术带头人。

小利奥•E•斯特林是宾夕法尼亚大学凯里法学院的迈克尔•L•瓦赫特法律和政策杰出研究员、哥伦比亚大学法学院艾拉•M•米尔斯坦全球市场和企业所有权中心的杰出高级研究员、特拉华州前首席大法官和校长,也在Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, & Katz律师事务所担任法律顾问。

雅普•温特是Phyleon Leadership and Governance的合伙人,在阿姆斯特丹自由大学担任公司法、治理和行为学教授。

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

Fifty years ago, Milton Friedman in the New York Times magazine proclaimed that the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. Directors have the duty to do what is in the interests of their masters, the shareholders, to make as much profit as possible. Friedman was hostile to the New Deal and European models of social democracy and urged business to use its muscle to reduce the effectiveness of unions, blunt environmental and consumer protection measures, and defang antitrust law. He sought to reduce consideration of human concerns within the corporate boardroom and legal requirements on business to treat workers, consumers, and society fairly.

Over the last 50 years, Friedman’s views became increasingly influential in the U.S. As a result, the power of the stock market and wealthy elites soared and consideration of the interests of workers, the environment, and consumers declined. Profound economic insecurity and inequality, a slow response to climate change, and undermined public institutions resulted. Using their wealth and power in the pursuit of profits, corporations led the way in loosening the external constraints that protected workers and other stakeholders against overreaching.

Under the dominant Friedman paradigm, corporations were constantly harried by all the mechanisms that shareholders had available—shareholder resolutions, takeovers, and hedge fund activism—to keep them narrowly focused on stockholder returns. And pushed by institutional investors, executive remuneration systems were increasingly focused on total stock returns. By making corporations the playthings of the stock market, it became steadily harder for corporations to operate in an enlightened way that reflected the real interests of their human investors in sustainable growth, fair treatment of workers, and protection of the environment.

Half a century later, it is clear that this narrow, stockholder-centered view of corporations has cost society severely. Well before the COVID-19 pandemic, the single-minded focus of business on profits was criticized for causing the degradation of nature and biodiversity, contributing to global warming, stagnating wages, and exacerbating economic inequality. The result is best exemplified by the drastic shift in gain sharing away from workers toward corporate elites, with stockholders and top management eating more of the economic pie.

Corporate America understood the threat that this way of thinking was having on the social compact and reacted through the 2019 corporate purpose statement of the Business Roundtable, emphasizing responsibility to stakeholders as well as shareholders. But the failure of many of the signatories to protect their stakeholders during the coronavirus pandemic has prompted cynicism about the original intentions of those signing the document, as well as their subsequent actions.

Stockholder advocates are right when then they claim that purpose statements on their own achieve little: Calling for corporate executives who answer to only one powerful constituency—stockholders in the form of highly assertive institutional investors—and have no legal duty to other stakeholders to run their corporations in a way that is fair to all stakeholders is not only ineffectual, it is naive and intellectually incoherent.

What is required is to match commitment to broader responsibility of corporations to society with a power structure that backs it up. That is what has been missing. Corporate law in the U.S. leaves it to directors and managers subject to potent stockholder power to give weight to other stakeholders. In principle, corporations can commit to purposes beyond profit and their stakeholders, but only if their powerful investors allow them to do so. Ultimately, because the law is permissive, it is in fact highly restrictive of corporations acting fairly for all their stakeholders because it hands authority to investors and financial markets for corporate control.

Absent any effective mechanism for encouraging adherence to the Roundtable statement, the system is stacked against those who attempt to do so. There is no requirement on corporations to look after their stakeholders and for the most part they do not, because if they did, they would incur the wrath of their shareholders. That was illustrated all too clearly by the immediate knee-jerk response of the Council of Institutional Investors to the Roundtable declaration last year, which expressed its disapproval by stating that the Roundtable had failed to recognize shareholders as owners as well as providers of capital, and that “accountability to everyone means accountability to no one.”

If the Roundtable is serious about shifting from shareholder primacy to purposeful business, two things need to happen. One is that the promise of the New Deal needs to be renewed, and protections for workers, the environment, and consumers in the U.S. need to be brought closer to the standards set in places like Germany and Scandinavia.

But to do that first thing, a second thing is necessary. Changes within company law itself must occur, so that corporations are better positioned to support the restoration of that framework and govern themselves internally in a manner that respects their workers and society. Changing the power structure within corporate law itself—to require companies to give fair consideration to stakeholders and temper their need to put profit above all other values—will also limit the ability and incentives for companies to weaken regulations that protect workers, consumers, and society more generally.

To make this change, corporate purpose has to be enshrined in the heart of corporate law as an expression of the broader responsibility of corporations to society and the duty of directors to ensure this. Laws already on the books of many states in the U.S. do exactly that by authorizing the public benefit corporation (PBC). A PBC has an obligation to state a public purpose beyond profit, to fulfill that purpose as part of the responsibilities of its directors, and to be accountable for so doing. This model is meaningfully distinct from the constituency statutes in some states that seek to strengthen stakeholder interests, but that stakeholder advocates condemn as ineffectual. PBCs have an affirmative duty to be good corporate citizens and to treat all stakeholders with respect. Such requirements are mandatory and meaningful, while constituency statutes are mushy.

The PBC model is growing in importance and is embraced by many younger entrepreneurs committed to the idea that making money in a way that is fair to everyone is the responsible path forward. But the model’s ultimate success depends on longstanding corporations moving to adopt it.

Even in the wake of the Roundtable’s high-minded statement, that has not yet happened, and for good reason. Although corporations can opt in to become a PBC, there is no obligation on them to do so and they need the support of their shareholders. It is relatively easy for founder-owned companies or companies with a relatively low number of stockholders to adopt PBC forms if their owners are so inclined. It is much tougher to obtain the approval of a dispersed group of institutional investors who are accountable to an even more dispersed group of individual investors. There is a serious coordination problem of achieving reform in existing corporations.

That is why the law needs to change. Instead of being an opt-in alternative to shareholder primacy, the PBC should be the universal standard for societally important corporations, which should be defined as ones with over $1 billion of revenues, as suggested by Sen. Elizabeth Warren. In the U.S., this would be done most effectively by corporations becoming PBCs under state law. The magic of the U.S. system has rested in large part on cooperation between the federal government and states, which provides society with the best blend of national standards and nimble implementation. This approach would build on that.

Corporate shareholders and directors enjoy substantial advantages and protections through U.S. law that are not extended to those who run their own businesses. In return for offering these privileges, society can reasonably expect to benefit, not suffer, from what corporations do. Making responsibility in society a duty in corporate law will reestablish the legitimacy of incorporation.

There are three pillars to this. The first is that corporations must be responsible corporate citizens, treating their workers and other stakeholders fairly, and avoiding externalities, such as carbon emissions, that cause unreasonable or disproportionate harm to others. The second is that corporations should seek to make profit by benefiting others. The third is that they should be able to demonstrate that they fulfill both criteria by measuring and reporting their performances against them.

The PBC model embraces all three elements and puts legal, and thus market, force behind them. Corporate managers, like most of us, take obligatory duties seriously. If they don’t, the PBC model allows for courts to issue orders, such as injunctions, holding corporations to their stakeholder and societal obligations. In addition, the PBC model requires fairness to all stakeholders at all stages of a corporation’s life, even when it is sold. The PBC model shifts power to socially responsible investment and index funds that focus on the long term and cannot gain from unsustainable approaches to growth that harm society.

Our proposal to amend corporate law to ensure responsible corporate citizenship will prompt a predictable outcry from vested interests and traditional academic quarters, claiming that it will be unworkable, devastating for entrepreneurship and innovation, undermine a capitalist system that has been an engine for growth and prosperity, and threaten jobs, pensions, and investment around the world. If putting the purpose of a business at the heart of corporate law does all of that, one might well wonder why we invented the corporation in the first place.

Of course, it will do exactly the opposite. Putting purpose into law will simplify, not complicate, the running of businesses by aligning what the law wants them to do with the reason why they are created. It will be a source of entrepreneurship, innovation, and inspiration to find solutions to problems that individuals, societies, and the natural world face. It will make markets and the capitalist system function better by rewarding positive contributions to well-being and prosperity, not wealth transfers at the expense of others. It will create meaningful, fulfilling jobs, support employees in employment and retirement, and encourage investment in activities that generate wealth for all.

We are calling for the universal adoption of the PBC for large corporations. We do so to save our capitalist system and corporations from the devastating consequences of their current approaches, and for the sake of our children, our societies, and the natural world.

Colin Mayer is the Peter Moores professor of management studies at the University of Oxford’s Said Business School, and academic lead of the Future of the Corporation program at the British Academy.

Leo E. Strine Jr. is the Michael L. Wachter distinguished fellow in law and policy at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, the Ira M. Millstein distinguished senior fellow at the Ira M. Millstein Center for Global Markets and Corporate Ownership at Columbia Law School, former chief justice and chancellor of Delaware, and of counsel at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen, & Katz.

Jaap Winter is a partner at Phyleon Leadership and Governance and professor of corporate law, governance, and behavior at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.