在接受我的电话采访时,卡尔加里市的市长纳希德•奈什正驱车一路向北,前往埃德蒙顿去省议会开会。这段路车程达三小时,一路上我们都在交谈。他沿着一段平坦的高速公路前行,背景传来GPS指路的声音,他开始介绍城市面临的挑战。石油价格跌跌不休,疫情来袭让情况更糟,卡尔加里财政状况格外紧张。面临戏剧性的经济衰退,人们越发关注奈什强调多年的问题,即卡尔加里对石油和天然气工业的过度依赖。

48岁的奈什曾经在麦肯锡担任顾问,向来以开朗友好著称,毕竟他是加拿大人。他是很乐观,但在直言评价卡尔加里经济状况时,从声音中能够听出一丝沮丧:“呃,不太好。”

突然,奈什的话停了下来,开始读路边一块广告牌,上面写着阿尔伯塔的宣传语:“实现经济多样化。”“对。”他冷冷地说。然后他笑着补充道:“说得挺到位。”

这句宣传语不仅简单,也很引人注目。奈什指出,这代表着加拿大阿尔伯塔省宣传的突然转向。“六个月前我可不会看到这种广告牌。”他说。如今,疫情导致的创伤把全世界最大的石油天然气中心之一长期争论的话题迅速改变。

卡尔加里人口有130万,是加拿大能源行业企业和金融中心。2010年奈什当选后,成为北美大城市的首位穆斯林市长。他借助红蓝中间派选民组成的“紫色浪潮”联盟赢得竞选,宣誓就职时恰逢20年繁荣期临近结束。奈什号召通过投资石油天然气以外的行业来巩固卡尔加里的经济实力。过去10年里,油价从每桶超过100美元暴跌到目前的不到40美元,而且一路走低,阿尔伯塔很多人的本能反应是静静等着下滑趋势逆转。而环保主义者的批评声势浩大又与日俱增,也让支持奈什的一些选民更加抗拒。

流沙

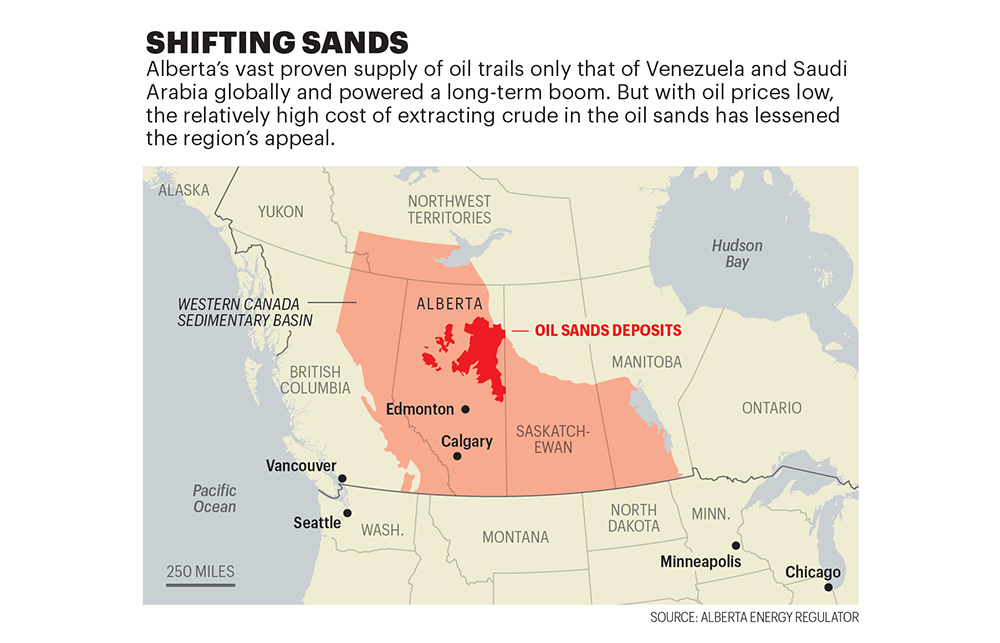

阿尔伯塔巨大的石油供应量在全球仅次于委内瑞拉和沙特阿拉伯,推动了长时间的繁荣。但由于油价较低,油砂开采原油的成本相对较高,削弱了该地区的吸引力。

来源:阿尔伯塔能源监管局

阿尔伯塔的能源主要是北部出产的所谓油砂。该地区的非常规石油储量庞大,已探明储量达1654亿桶,位居全球第三,仅次于委内瑞拉和沙特阿拉伯。油砂占加拿大石油产量的60%以上。也正因如此,阿尔伯塔成了国际上环保积极人士的目标。

油砂炼油必须从含油泥沙中提取和加工,成本高昂且伴随大量排放,比起传统钻探通常更类似露天开采。长期以来,航空拍摄的大量尾矿池,即开采过程中厚厚的油性副产品引发了环保人士抵制。近年,环保人士一直呼吁封闭Keystone XL输油管道,该管道可以向美国输送更多油砂原油。尽管特朗普政府努力推动管道项目,然而美国一项法律规定已经叫停建设。

多年来,油砂提供的税收收入确保阿尔伯塔的预算平衡,而且阿尔伯塔一直为联邦政府贡献收入,供其在全国重新分配。

然而,如今阿尔伯塔的会计师们发现了巨大的漏洞。今年8月,阿尔伯塔政府发布了本年度修订后的预算预测,赤字比2月的预测高出128亿美元,主要原因是石油天然气部门的资源收入预计比之前预测低30亿美元。与此同时,8月阿尔伯塔的失业率接近12%,在加拿大各省排名第二。预计今年阿尔伯塔经济将萎缩8.8%。去年,石油天然气以及采矿业占了该省GDP的26%,间接影响则更为广泛。因此,经济放缓让人很不安。

从许多方面来说,阿尔伯塔充分体现了从美国西得克萨斯州到中东等石油资源丰富地区的困境。疫情只是彻底揭露了阿尔伯塔在经济上面临挑战,导致问题更加严峻。这也是产油核心地区面临的兴衰转换难题。当形势一片大好时,人们没有动力考虑从利润丰厚的行业转移。日子不好过的时候则口袋空空。不过,打破“资源诅咒”很困难,阿尔伯塔的问题尤其麻烦,因为当地深居内陆,非常依赖南部的贸易伙伴美国,目前其96%的出口都是运往美国。同时,在政府和机构投资者支持下,越来越多的绿色能源倡导者正在全球范围推动加快淘汰化石燃料。阿尔伯塔必须顺应形势,否则可能在新能源经济中落后。

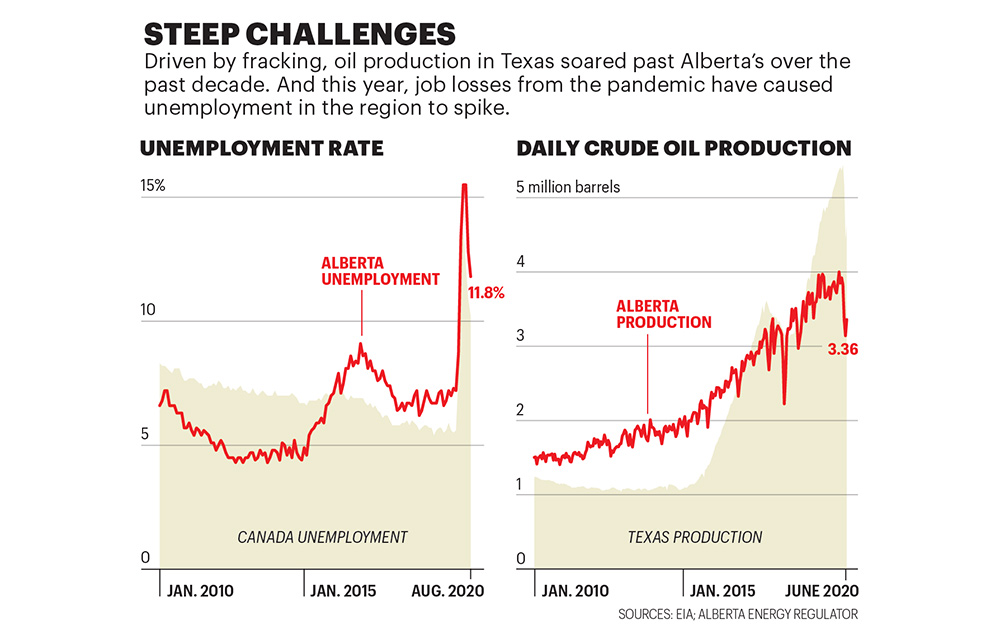

严峻的挑战

在水力压裂技术的推动下,过去十年里美国得州石油产量超过了阿尔伯塔。今年,受疫情影响,阿尔伯塔失业人数激增。

资料来源:美国能源信息署;阿尔伯塔能源监管局

这就是奈什为何认为阿尔伯塔别无选择,只能迅速改变对未来的看法。卡尔加里要接受发展清洁能源就业机会的新运动,也要加快在其他领域投资的步伐。

“有个非常著名的骑车保险杠贴纸。上面写着:‘上帝啊,再让我轰隆一次吧,这次一定不会糟蹋了。’”奈什边说边开车穿过草原。

他继续说:“这段时间我一直在说:‘我们不能糟蹋经济衰退。’我们特别擅长糟蹋繁荣。水平真的很高。我们真的不能浪费经济衰退带来的机会。”

如果现在卡尔加里还不能改变,还有机会改变吗?

我出生时恰逢石油危机。1989年11月,我出生在卡尔加里,当天沙特阿拉伯宣布发现了一处新的大油田。似乎世界上到处都是原油。当时油价仅为每桶20美元。种种因素促成了我的父母在卡尔加里的“银拖鞋沙龙”酒吧(Silver Slipper Saloon)相识,加入了前些年逐渐衰落的行业。(我父母一辈子都在能源行业。)

我开始上学时,出现了油砂扩张驱动的新一轮繁荣。这波繁荣时间最长,规模也最大。很快,咖啡连锁店想招新员工都挺难。郊区到处鲜花盛开。连十几岁的男孩都知道,辍学去钻台工作很快就能赚大钱。

当前这波下跌始于2014年,几个月里油价就下跌了超过50%。尽管后来有周期性反弹,但自那以后油价持续走低。最大原因是采用水力压裂技术的美国石油产量令人吃惊地激增。2010年,美国石油日产量约为550万桶。去年日均产量超过1220万桶。疫情导致的经济放缓只会加大油价下行压力。国际能源署的最近估计是,今年全球石油需求预计为平均每天9190万桶,比2019年减少810万桶。

虽然疫情过后油价可能再次攀升,但有迹象表明,类似上一波的繁荣可能永远不会重现。8月安永一份报告显示,自动化对阿尔伯塔50%的上游能源就业岗位造成威胁。卡尔加里经济发展委员会表示,为推动能源行业数字化程度,必须开展大规模再培训,主要针对卡尔加里多出的石油工程师和地球物理学家能再就业的工作岗位。在奈什领导下,卡尔加里一直努力推动经济发展。2018年,卡尔加里设立了1亿美元基金,向承诺创造就业机会的科技创业公司和非石油天然气行业的当地企业提供资助。但在疫情和油价暴跌的夹击下,一些能够创造就业机会的来源受到重创,比如曾经爆发式增长的餐馆和酿酒厂,以及落基山脉附近的旅游业。

阿尔伯塔跟一些石油资源丰富的经济体不同,多年来并没做到未雨绸缪。这方面最突出的是多年来靠着石油财富已积累1万亿美元主权财富基金的挪威。当地有130亿美元的阿尔伯塔储蓄信托基金(Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund),规模根本不足以填补缺口。虽然1976年基金成立以来,政府收入大幅增加,但基金市值却基本上未变。阿尔伯塔的财富主要投向建立全球一流的公共医疗和教育,税收也是全国最低。

当然,即便油价不出现大幅反弹,预计油气行业也不会很快消失。虽然有可能积极推进绿色经济转型,预计到2050年仍然会保留一些石油生产,问题只是从何处开采。挪威能源咨询公司Rystad energy预计,未来10年加拿大西部地区石油产量年增长率将接近2%,因为墨西哥和受危机重创的委内瑞拉产量下降,而阿尔伯塔对重质原油仍然有大量需求。但不少分析师表示,现在不会有油砂方面的新投资。一些国际石油公司,如法国道达尔公司已经完全撤出该地区。

石油行业从阿尔伯塔撤出,部分原因在于政治不确定性,即Keystone及其他石油运输管道能否获批。但最大的问题是在油砂炼油成本。Rystad Energy和总部位于爱丁堡的能源咨询公司Wood Mackenzie都将油砂炼油盈亏价格定在每桶45美元左右,一些项目成本能够维持在20至30美元之间。不过,另一些成本高得多。

油砂项目需要庞大的基础设施投入,通常需要40至50年才能够启动。哪怕是最高效的开发项目也要有非常密集的资本。2019年阿尔伯塔政府估计,最贵的矿业项目初始盈亏平衡价格高达每桶75美元或85美元。这个门槛相当高,尤其是当前银行和其他投资集团又面临着收紧化石燃料融资的压力。

奈什和政府同僚必须接受的另一个现实是,基本上不可能通过政策来实现油价上涨带动经济繁荣。阿尔伯塔大学的能源经济学家安德鲁•利奇表示,加拿大其他地区,尤其是大西洋沿岸省份,在鳕鱼捕捞和伐木业都已经历前所未有的萧条,可以说比阿尔伯塔更需要帮助。目前并未出现一鸣惊人的解决方案。阿尔伯塔经济繁荣的一大讽刺是,雇用的很多员工都是因为大西洋沿岸经济萧条才不得不另觅生路。“不管政府怎么推政策,也无法每年自动吸引数十亿美元的外国直接投资。”利奇说。

在阿尔伯塔,石油天然气工人普遍受过高等教育,专业化程度高,工资也很高。虽然科技行业蒸蒸日上,也无法保证新工作岗位能够达到相应标准。但也有阿尔伯塔人在默默努力。

利亚姆•希尔德布兰德曾经想利用在油田当焊工时学到的技能来推动绿色能源转型,但根本找不到工作。他说,有人认为石油天然气工人并不愿意从事可再生能源工作。事实并非如此。如果连工作机会都没有,怎么指望人们投身建设绿色的未来。

20岁时,希尔德布兰德在石油行业找到第一份工作。2010年,他回到大学攻读地理学位,主要关注绿色能源事业,但找不到工作。于是他又回到油砂矿当了六年焊工。“从一天开始,我的外号就是绿色和平。”他笑着说。尽管身边不少同事都有合理怀疑,但很多人承认内心很担心气候变化,也承受着行业繁荣萧条的压力。

2015年,随着油价暴跌,工作午餐时的谈话变得越发紧迫。“我们不是在讨论假设的情况了。”他说,“明天就可能失业。该怎么办?”

那一年,如今35岁的希尔德布兰德和石油行业的同事成立了“铁与地球”(Iron & Earth)非营利组织,倡导可持续能源投资。他们认为,全面能源转型将推动巨大的基础设施建设热潮,不仅包括风能和太阳能,也包括生物能、地热能和氢能发电厂。

愿景雄心勃勃,可惜与现实相去甚远。进展倒是有一些。今年,伯克希尔-哈撒韦能源公司加拿大子公司新投资的风电场将为阿尔伯塔东南部提供相当于7.9万户家庭用量的电力。2019年,可再生能源发电量不到总发电量的10%。但据加拿大风能协会统计,目前阿尔伯塔已经是全国第三大风能市场,装机容量达1685兆瓦。2017年,加拿大清洁能源部估计,清洁能源就业岗位有26358个,整体行业约占阿尔伯塔GDP的1%。6月,位于阿尔伯塔的环境非政府组织Pembina Institute表示,绿色能源转型过程中,预计到2030年将在阿尔伯塔创造6.7万个就业岗位,相当于能源部门现有员工的67%。

希尔德布兰德目前已经辞去石油行业的工作,全职经营“铁与地球”,他相信阿尔伯塔人已经准备好迎接大变革。“工人们都已经觉醒。”他说。

然而,并非每个阿尔伯塔人都对绿色能源的概念持开放态度。近年来,阿尔伯塔政治两极分化愈演愈烈,导致可持续性相关对话愈加困难。2020年3月加拿大广播公司CBC主持了一项民意调查,询问阿尔伯塔如何才能让经济重回正轨。调查显示,近40%的受访者提到要控制疫情或政府支持,还有约30%的受访者表示“需要经济多元化”,29%的受访者表示“加大石油投资”。此类指标与受访者的投票密切相关。2018年3月以来,自称政治上偏左派或右派的人有所增加,而自称保持中立的人减少了9%。

很多阿尔伯塔人对反对化石燃料的论点持怀疑态度。2018年Pembina Institute采取了一项判断人们对可持续能源态度的调查,叫“阿尔伯塔故事项目”,发现约半数参与者要么坚决拒绝气候变化的概念,要么怀疑气候变化到底是不是由人类行为造成。

企业界的观点不一。之前我采访的多名能源经济学家和专家表示,该地区最大规模的石油天然气公司高管极度怀疑气候变化,普遍支持现有的碳排放税。总部位于卡尔加里的石油天然气公司森科尔和塞诺佛斯都表示,2030年每桶油的碳排放可以降低30%。

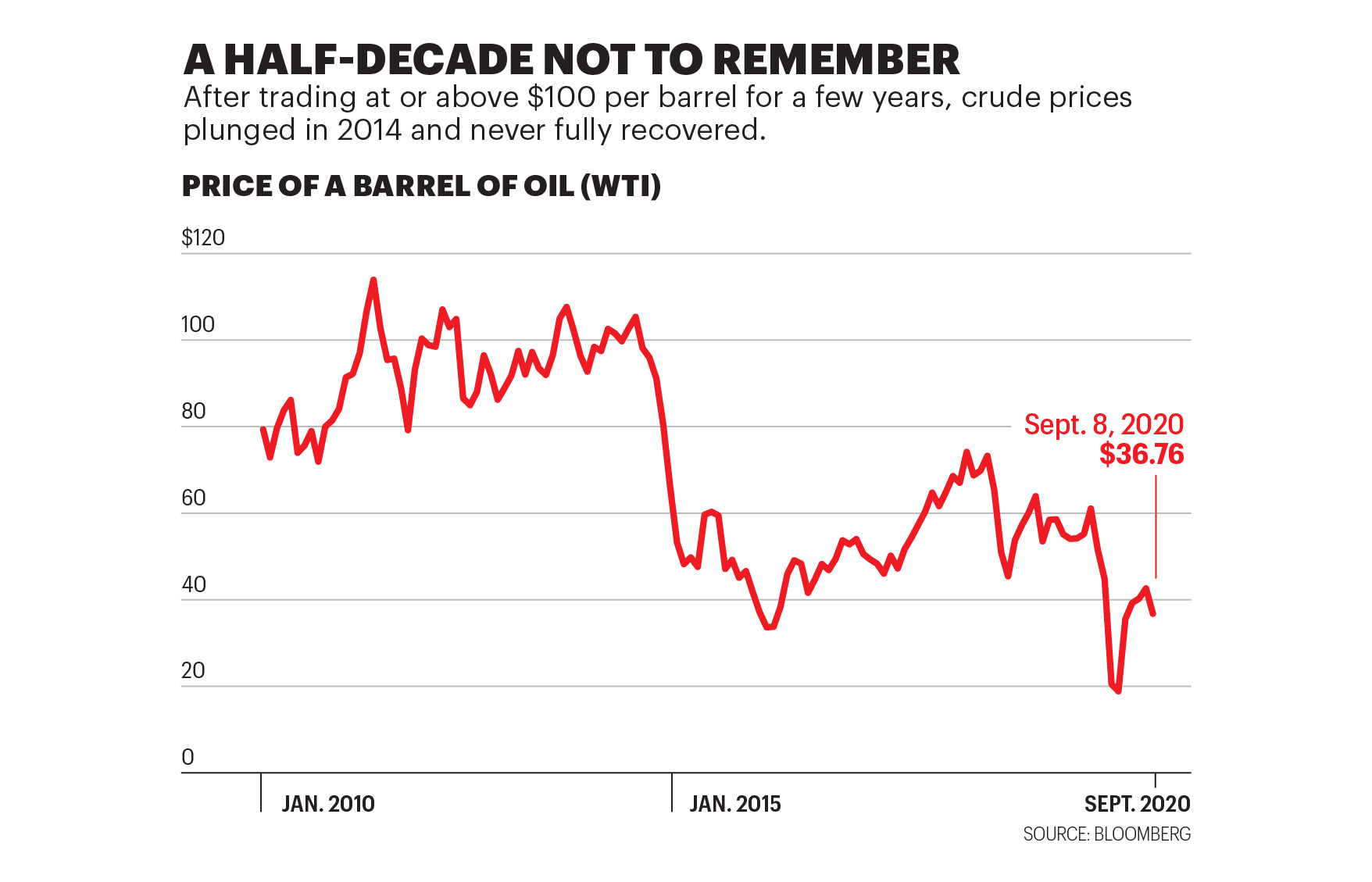

不堪回首的五年

原油价格保持每桶100美元以上数年之后,2014年出现暴跌,且未能反弹到之前水平。

来源:彭博社

近年来,科学家将越来越多的自然灾害与气候变化联系起来。2013年,洪水淹没了卡尔加里市的市中心,导致曲棍球场的看台升高。2016年,规模庞大绰号“野兽”的大火摧毁了麦克默里堡郊区一大片房屋,当地是油砂矿企业生活区。

尽管有种种让人体会到切身之痛的案例,但要明确提出应对气候变化的紧迫性以及与阿尔伯塔石油业务的联系,往往容易遭遇强烈的阻力。石油行业总喜欢提出,阿尔伯塔的油砂已经大幅降低了每桶石油的排放量,之前排放量一直为全球最高。加拿大石油生产商协会表示,1990年以来每桶油砂原油的排放量下降了32%。能源经济学家说,通过研究和开发确实减少了多个项目的排放量,其中有些降幅还很大。但油砂密集开采意味着,平均而言阿尔伯塔的石油产品仍比其他大多数原油更加偏能源密集。此外,今天产量增加也意味着同一时期内全行业绝对排放量增加。

各种争论中要理清头绪并不容易。45岁的迪安娜•伯加特以亲身经历出发,展示了如何在忠于行业和关注气候之间搭建桥梁。她的经验都来自实打实的亲身经历。当年伯加特35岁,在油砂矿区担任工程师期间与生母联系上,她的生母是经常抗议油砂的原住民女性。两人交流起来并不容易。“我学会了从爱和尊重出发,进行艰难的两极分化对话。”她说。

伯加特接受了自己的双重身份。她年轻时就在石油领域获得成功,后来才知道自己跟母亲一样属于原住民德恩和克里族。她想办法将种种观点加以融合。如今,伯加特是卡尔加里大学的教授,努力将原住民知识融入工程课程,尽量在项目早期阶段参考原住民意见。她还是咨询公司Indigenous Engineering Inclusion的创始人,与石油公司和原住民团体合作,处理从环境影响到创造就业机会等各方面事务。她说,选择离开石油行业投身创业,也是为了“融合”自身身份。她说,她尽最大的努力倾听每个人的心声,而且持续交谈,这也是她与母亲刚开始谈话时学到的策略。

1884年,阿尔弗雷德•欧内斯特•克罗斯于从蒙特利尔来到阿尔伯塔,两年后在卡尔加里以西建立了历史悠久的A7牧场。后来他成为阿尔伯塔上层,拥有牧场,支持石油天然气工业,从政,还跻身“四大”,即资助第一届卡尔加里牛仔节的四大赞助农场主之一,牛仔节是当地著名的牛仔竞技表演,持续十天。

克罗斯的农场成立约100年后,传给了孙子约翰。约翰•克罗斯决定打破惯例采用整体方式管理牧场,与天然草原的生态系统合作,不用化肥提高产量。他承认,在20世纪80年代,这一决定“确实不常见,也颇具争议”。这不是他唯一的奇怪决定。上世纪90年代,他建造了完全“脱离电网”的房子,主要依靠风能和太阳能发电。(20年后他宣布放弃,用回传统电力。他承认,完全依赖可再生能源“让人头疼”,尤其是冬天。)

今天,约翰•克罗斯相信,新能源转型过程中这块地可以发挥作用。他主张通过补偿对阿尔伯塔的生态系统进行再投资,也理解自然的碳汇功能。“所以我认为阿尔伯塔的石油、天然气和土地产权能够互惠互利。”他说。

说回高速公路,正在开车的市长奈什说,受到了新想法的鼓舞,希望阿尔伯塔人都能够做好准备,找到必要的共同出发点来践行广告牌上迫切的宣传语。

“你也看到了,最近政府已经从‘全押’石油天然气转向更加平衡。”奈什说,他正穿过大草原前往埃德蒙顿。“人人都想要工作。人人都想要可持续的经济。这些都应该超越党派偏见。”是时候像广告牌说的一样,通过采取实际行动来实现多元化了。

通过数据看石油区

26%

去年,阿尔伯塔GDP当中有26%与石油天然气行业有关,也包括采矿业。该行业对阿尔伯塔经济的间接影响更大

30亿美元

今年阿尔伯塔修订后预算中预计的资源收入缺口,主要因为油价下跌

67000个

据非营利组织Pembina Institute估计,到2030年,阿尔伯塔转型绿色能源可创造的岗位数量

96%

阿尔伯塔出口到美国的石油比例。

每桶45美元

业内咨询公司称,大多数油砂原油实现盈亏平衡的油价。某些项目中,盈亏平衡价格可能高达85美元。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年10月刊,标题为《石油热潮过去之后》。

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

加拿大石油天然气之都阿尔伯塔卡尔加里市中心附近公园里,一只狗在奔跑。

在接受我的电话采访时,卡尔加里市的市长纳希德•奈什正驱车一路向北,前往埃德蒙顿去省议会开会。这段路车程达三小时,一路上我们都在交谈。他沿着一段平坦的高速公路前行,背景传来GPS指路的声音,他开始介绍城市面临的挑战。石油价格跌跌不休,疫情来袭让情况更糟,卡尔加里财政状况格外紧张。面临戏剧性的经济衰退,人们越发关注奈什强调多年的问题,即卡尔加里对石油和天然气工业的过度依赖。

48岁的奈什曾经在麦肯锡担任顾问,向来以开朗友好著称,毕竟他是加拿大人。他是很乐观,但在直言评价卡尔加里经济状况时,从声音中能够听出一丝沮丧:“呃,不太好。”

突然,奈什的话停了下来,开始读路边一块广告牌,上面写着阿尔伯塔的宣传语:“实现经济多样化。”“对。”他冷冷地说。然后他笑着补充道:“说得挺到位。”

这句宣传语不仅简单,也很引人注目。奈什指出,这代表着加拿大阿尔伯塔省宣传的突然转向。“六个月前我可不会看到这种广告牌。”他说。如今,疫情导致的创伤把全世界最大的石油天然气中心之一长期争论的话题迅速改变。

卡尔加里人口有130万,是加拿大能源行业企业和金融中心。2010年奈什当选后,成为北美大城市的首位穆斯林市长。他借助红蓝中间派选民组成的“紫色浪潮”联盟赢得竞选,宣誓就职时恰逢20年繁荣期临近结束。奈什号召通过投资石油天然气以外的行业来巩固卡尔加里的经济实力。过去10年里,油价从每桶超过100美元暴跌到目前的不到40美元,而且一路走低,阿尔伯塔很多人的本能反应是静静等着下滑趋势逆转。而环保主义者的批评声势浩大又与日俱增,也让支持奈什的一些选民更加抗拒。

流沙

阿尔伯塔巨大的石油供应量在全球仅次于委内瑞拉和沙特阿拉伯,推动了长时间的繁荣。但由于油价较低,油砂开采原油的成本相对较高,削弱了该地区的吸引力。

来源:阿尔伯塔能源监管局

阿尔伯塔的能源主要是北部出产的所谓油砂。该地区的非常规石油储量庞大,已探明储量达1654亿桶,位居全球第三,仅次于委内瑞拉和沙特阿拉伯。油砂占加拿大石油产量的60%以上。也正因如此,阿尔伯塔成了国际上环保积极人士的目标。

油砂炼油必须从含油泥沙中提取和加工,成本高昂且伴随大量排放,比起传统钻探通常更类似露天开采。长期以来,航空拍摄的大量尾矿池,即开采过程中厚厚的油性副产品引发了环保人士抵制。近年,环保人士一直呼吁封闭Keystone XL输油管道,该管道可以向美国输送更多油砂原油。尽管特朗普政府努力推动管道项目,然而美国一项法律规定已经叫停建设。

从油砂中炼油伴随着大量排放。

多年来,油砂提供的税收收入确保阿尔伯塔的预算平衡,而且阿尔伯塔一直为联邦政府贡献收入,供其在全国重新分配。

然而,如今阿尔伯塔的会计师们发现了巨大的漏洞。今年8月,阿尔伯塔政府发布了本年度修订后的预算预测,赤字比2月的预测高出128亿美元,主要原因是石油天然气部门的资源收入预计比之前预测低30亿美元。与此同时,8月阿尔伯塔的失业率接近12%,在加拿大各省排名第二。预计今年阿尔伯塔经济将萎缩8.8%。去年,石油天然气以及采矿业占了该省GDP的26%,间接影响则更为广泛。因此,经济放缓让人很不安。

从许多方面来说,阿尔伯塔充分体现了从美国西得克萨斯州到中东等石油资源丰富地区的困境。疫情只是彻底揭露了阿尔伯塔在经济上面临挑战,导致问题更加严峻。这也是产油核心地区面临的兴衰转换难题。当形势一片大好时,人们没有动力考虑从利润丰厚的行业转移。日子不好过的时候则口袋空空。不过,打破“资源诅咒”很困难,阿尔伯塔的问题尤其麻烦,因为当地深居内陆,非常依赖南部的贸易伙伴美国,目前其96%的出口都是运往美国。同时,在政府和机构投资者支持下,越来越多的绿色能源倡导者正在全球范围推动加快淘汰化石燃料。阿尔伯塔必须顺应形势,否则可能在新能源经济中落后。

严峻的挑战

在水力压裂技术的推动下,过去十年里美国得州石油产量超过了阿尔伯塔。今年,受疫情影响,阿尔伯塔失业人数激增。

资料来源:美国能源信息署;阿尔伯塔能源监管局

这就是奈什为何认为阿尔伯塔别无选择,只能迅速改变对未来的看法。卡尔加里要接受发展清洁能源就业机会的新运动,也要加快在其他领域投资的步伐。

“有个非常著名的骑车保险杠贴纸。上面写着:‘上帝啊,再让我轰隆一次吧,这次一定不会糟蹋了。’”奈什边说边开车穿过草原。

他继续说:“这段时间我一直在说:‘我们不能糟蹋经济衰退。’我们特别擅长糟蹋繁荣。水平真的很高。我们真的不能浪费经济衰退带来的机会。”

如果现在卡尔加里还不能改变,还有机会改变吗?

我出生时恰逢石油危机。1989年11月,我出生在卡尔加里,当天沙特阿拉伯宣布发现了一处新的大油田。似乎世界上到处都是原油。当时油价仅为每桶20美元。种种因素促成了我的父母在卡尔加里的“银拖鞋沙龙”酒吧(Silver Slipper Saloon)相识,加入了前些年逐渐衰落的行业。(我父母一辈子都在能源行业。)

我开始上学时,出现了油砂扩张驱动的新一轮繁荣。这波繁荣时间最长,规模也最大。很快,咖啡连锁店想招新员工都挺难。郊区到处鲜花盛开。连十几岁的男孩都知道,辍学去钻台工作很快就能赚大钱。

当前这波下跌始于2014年,几个月里油价就下跌了超过50%。尽管后来有周期性反弹,但自那以后油价持续走低。最大原因是采用水力压裂技术的美国石油产量令人吃惊地激增。2010年,美国石油日产量约为550万桶。去年日均产量超过1220万桶。疫情导致的经济放缓只会加大油价下行压力。国际能源署的最近估计是,今年全球石油需求预计为平均每天9190万桶,比2019年减少810万桶。

虽然疫情过后油价可能再次攀升,但有迹象表明,类似上一波的繁荣可能永远不会重现。8月安永一份报告显示,自动化对阿尔伯塔50%的上游能源就业岗位造成威胁。卡尔加里经济发展委员会表示,为推动能源行业数字化程度,必须开展大规模再培训,主要针对卡尔加里多出的石油工程师和地球物理学家能再就业的工作岗位。在奈什领导下,卡尔加里一直努力推动经济发展。2018年,卡尔加里设立了1亿美元基金,向承诺创造就业机会的科技创业公司和非石油天然气行业的当地企业提供资助。但在疫情和油价暴跌的夹击下,一些能够创造就业机会的来源受到重创,比如曾经爆发式增长的餐馆和酿酒厂,以及落基山脉附近的旅游业。

阿尔伯塔跟一些石油资源丰富的经济体不同,多年来并没做到未雨绸缪。这方面最突出的是多年来靠着石油财富已积累1万亿美元主权财富基金的挪威。当地有130亿美元的阿尔伯塔储蓄信托基金(Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund),规模根本不足以填补缺口。虽然1976年基金成立以来,政府收入大幅增加,但基金市值却基本上未变。阿尔伯塔的财富主要投向建立全球一流的公共医疗和教育,税收也是全国最低。

当然,即便油价不出现大幅反弹,预计油气行业也不会很快消失。虽然有可能积极推进绿色经济转型,预计到2050年仍然会保留一些石油生产,问题只是从何处开采。挪威能源咨询公司Rystad energy预计,未来10年加拿大西部地区石油产量年增长率将接近2%,因为墨西哥和受危机重创的委内瑞拉产量下降,而阿尔伯塔对重质原油仍然有大量需求。但不少分析师表示,现在不会有油砂方面的新投资。一些国际石油公司,如法国道达尔公司已经完全撤出该地区。

石油行业从阿尔伯塔撤出,部分原因在于政治不确定性,即Keystone及其他石油运输管道能否获批。但最大的问题是在油砂炼油成本。Rystad Energy和总部位于爱丁堡的能源咨询公司Wood Mackenzie都将油砂炼油盈亏价格定在每桶45美元左右,一些项目成本能够维持在20至30美元之间。不过,另一些成本高得多。

油砂项目需要庞大的基础设施投入,通常需要40至50年才能够启动。哪怕是最高效的开发项目也要有非常密集的资本。2019年阿尔伯塔政府估计,最贵的矿业项目初始盈亏平衡价格高达每桶75美元或85美元。这个门槛相当高,尤其是当前银行和其他投资集团又面临着收紧化石燃料融资的压力。

奈什和政府同僚必须接受的另一个现实是,基本上不可能通过政策来实现油价上涨带动经济繁荣。阿尔伯塔大学的能源经济学家安德鲁•利奇表示,加拿大其他地区,尤其是大西洋沿岸省份,在鳕鱼捕捞和伐木业都已经历前所未有的萧条,可以说比阿尔伯塔更需要帮助。目前并未出现一鸣惊人的解决方案。阿尔伯塔经济繁荣的一大讽刺是,雇用的很多员工都是因为大西洋沿岸经济萧条才不得不另觅生路。“不管政府怎么推政策,也无法每年自动吸引数十亿美元的外国直接投资。”利奇说。

在阿尔伯塔,石油天然气工人普遍受过高等教育,专业化程度高,工资也很高。虽然科技行业蒸蒸日上,也无法保证新工作岗位能够达到相应标准。但也有阿尔伯塔人在默默努力。

利亚姆•希尔德布兰德曾经想利用在油田当焊工时学到的技能来推动绿色能源转型,但根本找不到工作。他说,有人认为石油天然气工人并不愿意从事可再生能源工作。事实并非如此。如果连工作机会都没有,怎么指望人们投身建设绿色的未来。

20岁时,希尔德布兰德在石油行业找到第一份工作。2010年,他回到大学攻读地理学位,主要关注绿色能源事业,但找不到工作。于是他又回到油砂矿当了六年焊工。“从一天开始,我的外号就是绿色和平。”他笑着说。尽管身边不少同事都有合理怀疑,但很多人承认内心很担心气候变化,也承受着行业繁荣萧条的压力。

希德布拉姆在石油行业工作多年。如今他负责一家非营利组织,倡导投资可持续能源。

2015年,随着油价暴跌,工作午餐时的谈话变得越发紧迫。“我们不是在讨论假设的情况了。”他说,“明天就可能失业。该怎么办?”

那一年,如今35岁的希尔德布兰德和石油行业的同事成立了“铁与地球”(Iron & Earth)非营利组织,倡导可持续能源投资。他们认为,全面能源转型将推动巨大的基础设施建设热潮,不仅包括风能和太阳能,也包括生物能、地热能和氢能发电厂。

愿景雄心勃勃,可惜与现实相去甚远。进展倒是有一些。今年,伯克希尔-哈撒韦能源公司加拿大子公司新投资的风电场将为阿尔伯塔东南部提供相当于7.9万户家庭用量的电力。2019年,可再生能源发电量不到总发电量的10%。但据加拿大风能协会统计,目前阿尔伯塔已经是全国第三大风能市场,装机容量达1685兆瓦。2017年,加拿大清洁能源部估计,清洁能源就业岗位有26358个,整体行业约占阿尔伯塔GDP的1%。6月,位于阿尔伯塔的环境非政府组织Pembina Institute表示,绿色能源转型过程中,预计到2030年将在阿尔伯塔创造6.7万个就业岗位,相当于能源部门现有员工的67%。

希尔德布兰德目前已经辞去石油行业的工作,全职经营“铁与地球”,他相信阿尔伯塔人已经准备好迎接大变革。“工人们都已经觉醒。”他说。

然而,并非每个阿尔伯塔人都对绿色能源的概念持开放态度。近年来,阿尔伯塔政治两极分化愈演愈烈,导致可持续性相关对话愈加困难。2020年3月加拿大广播公司CBC主持了一项民意调查,询问阿尔伯塔如何才能让经济重回正轨。调查显示,近40%的受访者提到要控制疫情或政府支持,还有约30%的受访者表示“需要经济多元化”,29%的受访者表示“加大石油投资”。此类指标与受访者的投票密切相关。2018年3月以来,自称政治上偏左派或右派的人有所增加,而自称保持中立的人减少了9%。

很多阿尔伯塔人对反对化石燃料的论点持怀疑态度。2018年Pembina Institute采取了一项判断人们对可持续能源态度的调查,叫“阿尔伯塔故事项目”,发现约半数参与者要么坚决拒绝气候变化的概念,要么怀疑气候变化到底是不是由人类行为造成。

企业界的观点不一。之前我采访的多名能源经济学家和专家表示,该地区最大规模的石油天然气公司高管极度怀疑气候变化,普遍支持现有的碳排放税。总部位于卡尔加里的石油天然气公司森科尔和塞诺佛斯都表示,2030年每桶油的碳排放可以降低30%。

不堪回首的五年

原油价格保持每桶100美元以上数年之后,2014年出现暴跌,且未能反弹到之前水平。

来源:彭博社

近年来,科学家将越来越多的自然灾害与气候变化联系起来。2013年,洪水淹没了卡尔加里市的市中心,导致曲棍球场的看台升高。2016年,规模庞大绰号“野兽”的大火摧毁了麦克默里堡郊区一大片房屋,当地是油砂矿企业生活区。

尽管有种种让人体会到切身之痛的案例,但要明确提出应对气候变化的紧迫性以及与阿尔伯塔石油业务的联系,往往容易遭遇强烈的阻力。石油行业总喜欢提出,阿尔伯塔的油砂已经大幅降低了每桶石油的排放量,之前排放量一直为全球最高。加拿大石油生产商协会表示,1990年以来每桶油砂原油的排放量下降了32%。能源经济学家说,通过研究和开发确实减少了多个项目的排放量,其中有些降幅还很大。但油砂密集开采意味着,平均而言阿尔伯塔的石油产品仍比其他大多数原油更加偏能源密集。此外,今天产量增加也意味着同一时期内全行业绝对排放量增加。

身为长期从事石油天然气行业的资深人士,同时也是原住民女性,迪安娜•伯加特努力将行业评论家和支持者的观点结合起来。

各种争论中要理清头绪并不容易。45岁的迪安娜•伯加特以亲身经历出发,展示了如何在忠于行业和关注气候之间搭建桥梁。她的经验都来自实打实的亲身经历。当年伯加特35岁,在油砂矿区担任工程师期间与生母联系上,她的生母是经常抗议油砂的原住民女性。两人交流起来并不容易。“我学会了从爱和尊重出发,进行艰难的两极分化对话。”她说。

伯加特接受了自己的双重身份。她年轻时就在石油领域获得成功,后来才知道自己跟母亲一样属于原住民德恩和克里族。她想办法将种种观点加以融合。如今,伯加特是卡尔加里大学的教授,努力将原住民知识融入工程课程,尽量在项目早期阶段参考原住民意见。她还是咨询公司Indigenous Engineering Inclusion的创始人,与石油公司和原住民团体合作,处理从环境影响到创造就业机会等各方面事务。她说,选择离开石油行业投身创业,也是为了“融合”自身身份。她说,她尽最大的努力倾听每个人的心声,而且持续交谈,这也是她与母亲刚开始谈话时学到的策略。

1884年,阿尔弗雷德•欧内斯特•克罗斯于从蒙特利尔来到阿尔伯塔,两年后在卡尔加里以西建立了历史悠久的A7牧场。后来他成为阿尔伯塔上层,拥有牧场,支持石油天然气工业,从政,还跻身“四大”,即资助第一届卡尔加里牛仔节的四大赞助农场主之一,牛仔节是当地著名的牛仔竞技表演,持续十天。

克罗斯的农场成立约100年后,传给了孙子约翰。约翰•克罗斯决定打破惯例采用整体方式管理牧场,与天然草原的生态系统合作,不用化肥提高产量。他承认,在20世纪80年代,这一决定“确实不常见,也颇具争议”。这不是他唯一的奇怪决定。上世纪90年代,他建造了完全“脱离电网”的房子,主要依靠风能和太阳能发电。(20年后他宣布放弃,用回传统电力。他承认,完全依赖可再生能源“让人头疼”,尤其是冬天。)

农场主约翰•克罗斯在阿尔伯塔南顿附近历史悠久的A7牧场上。

今天,约翰•克罗斯相信,新能源转型过程中这块地可以发挥作用。他主张通过补偿对阿尔伯塔的生态系统进行再投资,也理解自然的碳汇功能。“所以我认为阿尔伯塔的石油、天然气和土地产权能够互惠互利。”他说。

说回高速公路,正在开车的市长奈什说,受到了新想法的鼓舞,希望阿尔伯塔人都能够做好准备,找到必要的共同出发点来践行广告牌上迫切的宣传语。

“你也看到了,最近政府已经从‘全押’石油天然气转向更加平衡。”奈什说,他正穿过大草原前往埃德蒙顿。“人人都想要工作。人人都想要可持续的经济。这些都应该超越党派偏见。”是时候像广告牌说的一样,通过采取实际行动来实现多元化了。

通过数据看石油区

26%

去年,阿尔伯塔GDP当中有26%与石油天然气行业有关,也包括采矿业。该行业对阿尔伯塔经济的间接影响更大

30亿美元

今年阿尔伯塔修订后预算中预计的资源收入缺口,主要因为油价下跌

67000个

据非营利组织Pembina Institute估计,到2030年,阿尔伯塔转型绿色能源可创造的岗位数量

96%

阿尔伯塔出口到美国的石油比例。

每桶45美元

业内咨询公司称,大多数油砂原油实现盈亏平衡的油价。某些项目中,盈亏平衡价格可能高达85美元。(财富中文网)

本文另一版本登载于《财富》杂志2020年10月刊,标题为《石油热潮过去之后》。

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

The Mayor of Calgary is driving north. Naheed Nenshi is making the three-hour trip to a meeting of the provincial legislature in Edmonton, and I’m along for the ride via speakerphone. As he heads down a flat stretch of highway, the GPS bleating instructions in the background, Nenshi begins laying out the challenges that his city is facing. A prolonged slump in oil prices, made worse by the pandemic, has severely strained Calgary’s finances. And the dramatic downturn has put a new spotlight on a problem that Nenshi has been talking about for years: the region’s unhealthy overdependence on the oil and gas industry.

A onetime McKinsey consultant, Nenshi, 48, is famously cheerful and friendly; he is, after all, Canadian. So he comes across as pretty upbeat. But it’s possible to detect just a touch of frustration in his voice as he offers a blunt assessment of his city’s economic situation: “Uh, not great.”

Suddenly, Nenshi interrupts himself to read a billboard he’s driving past with a message from the government of Alberta: “Diversify Our Economy.” “That’s it,” he says drily. Then he adds, chuckling: “That’s all it says.”

The language is striking for more than its simplicity. Nenshi points out that it represents a sudden shift in messaging from the government of the Canadian province. “I would not have seen that billboard six months ago,” he says. The trauma of the COVID-19 crisis, however, has quickly reshaped a long-running debate in one of the world’s biggest strongholds for the oil and gas business.

Calgary, a city of 1.3 million people, is the corporate and financial headquarters of Canada’s energy industry. When Nenshi was elected in 2010, he became the first Muslim mayor of a major North American city. He rode to victory on a “purple wave” coalition of red and blue centrist voters and took office near the end of a two-decade boom. Nenshi touted plans to build on Calgary’s economic strength by investing in industries outside of oil and gas. But as oil prices have tumbled from above $100 per barrel over the past decade to the current level below $40—falling even lower along the way—the instinct of many of his fellow Albertans has been to hunker down and wait for the slide to reverse. And a loud and growing chorus of criticism from environmentalists has caused some of Nenshi’s constituents to grow even more defiant.

Alberta’s energy wealth is derived primarily from the so-called oil sands located in the region’s north. The area’s vast unconventional petroleum deposits add up to proven reserves of 165.4 billion barrels—the third-largest total in the world after Venezuela and Saudi Arabia. The sands are the source of more than 60% of Canada’s oil production. They have also made Alberta a global target for activists.

Crude from the oil sands must be extracted and processed from a sandy sludge, in a costly and emissions-intensive process that often more closely resembles open-pit mining than conventional drilling. Aerial photos of the vast ponds of tailings—a thick, oily by-product of the extraction process—have long sparked pushback by environmentalists. Blocking the Keystone XL pipeline, which would bring additional oil-sands crude to the U.S., has been a major priority of environmental campaigners in recent years. A legal effort has successfully stopped construction in the U.S. for the time being, despite the Trump administration’s efforts to push the pipeline ahead.

For years, tax revenues from the oil sands helped fund robust and balanced budgets in Alberta. And the province still makes a net contribution to the federal government that is redistributed across the country.

Today, however, the province’s accountants are looking at a gaping hole. In August, the Alberta government released a revised budget forecast for the current year with a deficit that was $12.8 billion larger than projected back in February. Resource revenues, mainly from the oil and gas sector, are expected to be $3 billion below the original projection. The unemployment rate in Alberta, meanwhile, stood at nearly 12% in August, the second-highest of any province in the country. And the province’s economy is expected to contract 8.8% this year. Last year, oil and gas, along with mining, accounted for 26% of Alberta’s GDP, and its indirect impact was even bigger. So the slowdown stings.

In many ways, Alberta is emblematic of the struggle going on in oil-rich areas around the world, from West Texas to the Middle East. The pandemic has merely laid bare and made even starker the economic challenges Alberta was already facing—the essential conundrums of boom and bust at the heart of any oil region. When times are good, there’s little motivation to shift attention away from a lucrative sector. When times are bad, there’s no money. But while breaking the “resource curse” is always hard, the problem is especially vexing in Alberta, which is landlocked and dependent on its trading partner to the south—the U.S. is the destination for 96% of its exports. Meanwhile, green-energy advocates—increasingly with the heft of governments and institutional investors behind them—are gaining new traction globally in the push to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels. Alberta must adapt, or it could be left behind in the new energy economy.

That’s why Nenshi believes that the region has no choice but to change how it sees its future, and quickly. Calgary must embrace a nascent movement to develop clean-energy jobs, and up the pace of its investment in other areas.

“There is a very famous bumper sticker. And it says, ‘God, grant me another boom, I promise not to piss it away this time,’ ” says Nenshi as his car rolls through the prairie.

He continues: “What I’ve been saying for some time is, ‘We can’t piss away the downturn, either.’ We’re exceptionally good at pissing away booms. We’re world-class at it. But we cannot actually afford to piss away a downturn.”

If Calgary can’t change now, can it ever?

*****

My arrival in this world coincided with an oil bust. I was born in Calgary in November 1989, on the same day that Saudi Arabia announced the discovery of a major new oilfield. The world was seemingly awash in crude. And it was trading at just $20 a barrel. All of which meant that the industry that had drawn my parents—who met at a Calgary bar called the Silver Slipper Saloon—to the city earlier that decade was in decline. (Both of my parents have spent their careers in the energy sector.)

By the time I was starting school, a new boom had begun, driven by the expansion of the oil sands. It would be the longest, biggest boom of all. Before long, coffee chains were struggling to find staff; the suburbs were blooming in every direction; and teenage boys knew they could get big money, fast, by dropping out to work on the rigs.

The current reckoning really began in 2014, when oil prices dropped by more than 50% in a matter of months. Despite periodic rallies, oil has remained persistently lower since then. The biggest reason has been the astonishing, fracking-enabled surge in U.S. oil production. In 2010, the U.S. produced some 5.5 million barrels per day of oil. Last year, the average was over 12.2 million barrels per day. Now the coronavirus-driven economic slowdown has only increased the downward pressure on prices. The most recent estimate from the International Energy Agency is that global oil demand is expected to average 91.9 million barrels per day this year—that’s 8.1 million barrels per day less than in 2019.

While it’s possible oil prices could climb again post-pandemic, there are signs that another boom like the last one may never come back. Automation threatens 50% of upstream energy jobs in the province, according to an August report by EY. And Calgary Economic Development, an economic council, says that retraining for jobs in a more digital energy sector—largely for the kinds of jobs that can repurpose Calgary’s surplus of petroleum engineers and geophysicists—must happen on a massive scale. The city of Calgary, led by Nenshi, has been trying to stoke new economic development. In 2018, the city created a $100 million fund to give grants to tech startups and other local businesses outside the oil and gas industry that pledge to create jobs. But the pairing of the pandemic and the oil slump has also hit some alternative sources of job creation—like what was an exploding restaurant and brewery scene, and tourism around the Rockies.

Unlike some oil-rich economies—notably Norway, which socked away its petroleum riches over the years to amass what is now a $1 trillion sovereign wealth fund—Alberta hasn’t saved much for a rainy day. The province’s own Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund, with some $13 billion in assets, is simply not large enough to plug the gap. While government revenue has soared since 1976, when the fund was created, its value has essentially remained flat: Alberta’s riches, instead, went to its world-class public health care and education—and toward the lowest taxes in the country.

Of course, the oil and gas sector is not expected to disappear any time soon, even if prices don’t rise dramatically. Even under aggressive forecasts for transitioning to a green economy, some oil production is still expected to be in place by 2050—it’s simply a matter of where it will come from. The Norwegian energy consultancy Rystad Energy still expects oil production across western Canada to grow by close to 2% annually for the next decade, with demand for Alberta’s heavier-style crude bolstered by declining output from Mexico and crisis-wracked Venezuela. But new investment in the oil sands in particular is nonexistent right now, according to a range of analysts. Some international oil companies, such as French giant Total, have pulled out of the region completely.

The industry’s pullback from Alberta can be chalked up in part to political uncertainty over whether or not Keystone and other pipelines to bring more oil out of the region will be approved. But the biggest issue is the cost of producing crude in the oil sands. Both Rystad Energy and Wood Mackenzie, the Edinburgh-based energy consultancy, put the break-even price for existing oil-sands production at around $45 per barrel, with some projects able to keep the lights on in the $20 to $30 range. For some projects, though, the price is much higher.

Oil-sands projects are vast pieces of infrastructure and typically require 40- to 50-year commitments to get off the ground. And even the most efficient developments are hugely capital intensive. The Alberta government estimated in 2019 that the most expensive mining-style projects’ initial break-even price is as steep as $75 or $85 per barrel. That’s a very high bar to meet, especially when banks and other investment groups are under pressure to tighten financing for fossil-fuel projects.

Another reality that Nenshi and his peers in government must accept is that economic prosperity on the scale of an oil boom is basically impossible to manufacture through policy. In fact, other parts of Canada—particularly the Atlantic provinces, which already lived through their own epic busts in the cod fishing and logging industries—arguably need help even more than Alberta, says Andrew Leach, an energy economist at the University of Alberta. And yet there have been few blockbuster solutions. One of the great ironies of the Alberta boom was that it employed so many of the people whose economic futures had been displaced by the busts in Atlantic Canada that came before. “There’s nothing that a government policy can do that’s automatically going to bring in billions of dollars of foreign direct investment every year,” Leach says.

The average oil and gas worker in Alberta is highly educated, specialized, and well-paid. Despite the sparkle of the tech economy, there is no guarantee that the new jobs that might arrive will match that standard. But there are Albertans who are determined to do their best to make it so.

*****

Lliam Hildebrand wanted to use his skills as a welder in the oil patch to assist the green-energy transition—he just couldn’t get a job. There’s an assumption that oil and gas workers don’t want to work in renewable energy, he says. But that’s not the case. The truth is that you can’t expect people to jump on a green future without a job.

Hildebrand took his first job in the oil business at age 20. In 2010, he went back to university to get a degree in geography with an eye toward a career in green energy—but no job offers materialized. So he returned to the oil sands to work as a welder for another six years. “I was nicknamed Greenpeace, like day one,” he says with a laugh. But while many of his colleagues were legitimately skeptical, others admitted that worries over climate change, or the stress of boom and bust, were wearing on them.

By 2015, with oil prices crashing, the conversations over lunch in the work camps gained new urgency. “We weren’t discussing a hypothetical situation,” he says. “We might not have a job tomorrow. What are we going to do about that?”

That year Hildebrand, now 35, and a group of his fellow oil-sector workers, formed a nonprofit called Iron & Earth to advocate for sustainable energy investment. They argue that a full energy transition will produce a vast infrastructure building boom, across not just wind and solar, but biomass, geothermal, and hydrogen plants.

It’s an ambitious vision—and far from the current reality. But there are signs of progress. This year a new wind farm funded by Berkshire Hathaway Energy's Canadian subsidiary will power the equivalent of 79,000 homes in southeast Alberta. Renewables made up less than 10% of the province’s electricity generation in 2019. But Alberta is now the country’s third-largest wind market, with 1,685 megawatts of installed capacity, according to the Canadian Wind Energy association. In 2017, Clean Energy Canada estimated that the province was home to 26,358 jobs in clean energy, with the sector representing about 1% of the province’s GDP. In June, the Pembina Institute, an Alberta-based environmental NGO, said it estimated 67,000 jobs—the equivalent of 67% of the current employees of the resources sector in the province—could be created by 2030 as part of a green-energy transition.

Hildebrand, who left his oil job to run Iron & Earth full-time, believes that Albertans are ready to embrace big changes. There is a “whole awakening among workers,” he says.

*****

Not everyone in the province is so open to the concept of green energy. In recent years, Alberta has become more politically polarized, and that has made conversations about sustainability more difficult. A poll by the Canadian broadcaster CBC in March 2020 asked Albertans what the province needed to get its economy back on track. While nearly 40% mentioned the need to control pandemic or government support, some 30% of respondents said “economic diversification,” while 29% said “double down on oil.” Such markers were closely linked to how respondents vote, the survey noted. And since March 2018, those self-reporting that they are on either the left or the right politically have grown, while those reporting they are in the center shrunk by 9%.

Many Albertans are dubious about the arguments against fossil fuels. A 2018 effort by the Pembina Institute to gauge attitudes about sustainability, called The Alberta Narratives Project, found that about half of the people who participated either rejected the concept of climate change outright or doubted that it is caused by human behavior.

Within the corporate community, views are mixed. Multiple energy economists and experts I spoke with said climate-change doubt is unheard-of among executives at the largest oil and gas companies in the region, and support for an existing carbon tax is widespread. Both Suncor and Cenovus, Calgary-based oil and gas companies, have said they would reduce their per-barrel emissions intensity by 30% by 2030.

There have been plenty of examples in recent years of the damaging natural disasters that scientists are increasingly connecting to climate change. In 2013, flooding engulfed downtown Calgary, rising up the stands at the city’s hockey stadium. And in 2016, a fire so massive it was nicknamed “The Beast” eviscerated swaths of suburban homes in Fort McMurray, the company town that serves the oil sands.

Despite these visceral examples, broaching the urgency of addressing climate change and how it intersects with Alberta’s oil sector tends to come up against stout resistance. One argument the industry likes to make is that Alberta’s oil sands have dramatically reduced their emissions per barrel, which have historically been among the highest in the world. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers says that oil-sands emissions per barrel have fallen by 32% since 1990. And energy economists say it’s true that research and development has reduced per-barrel emissions across many of the projects, in some cases dramatically. But the intense extraction process in the oil sands means that, on average, Alberta’s product is still more energy-intensive than most other barrels. Plus, higher production volumes today mean that absolute emissions from the sector have increased over that same period.

Navigating these debates can be tricky. Deanna Burgart, 45, offers herself as an example of how to bridge the gap between loyalty to the industry and concern about the climate. She has learned from her own hard-won experience. Burgart was 35 and working as an engineer in the oil sands when she developed a relationship with her birth mother—an Indigenous woman and regular protester against the oil sands. It wasn’t easy. “I learned how to have these difficult, polarized conversations from a place of love and respect,” she says.

Burgart embraced her dual identities. She had found early success in the oil business. And now she learned that she was a Dene and Cree woman on her mother’s side. She sought a way to combine these perspectives. Today, Burgart is a teaching chair focused on integrating Indigenous knowledge into the engineering curriculum at the University of Calgary, working to bring First Nations perspective into projects at the earliest stages. She is also the founder of Indigenous Engineering Inclusion, a consulting company, where she works with oil companies and First Nations groups to address everything from environmental impact to the prospects for job creation. She describes the choice to quit her job in the sector and start her own business as a choice to “converge” her identities. These days she does her best, she says, to listen to everyone, and just keep talking—a strategy she learned in those early conversations with her mom.

*****

Alfred Ernest Cross first arrived in Alberta from Montréal in 1884, founding the historic A7 Ranche just west of Calgary two years later. He would go on to become Albertan royalty: a ranchman, a proponent of the oil and gas industry, a politician, and one of the “Big Four”—the four ranchers that financed the first Calgary Stampede, the city’s famous 10-day festival and rodeo.

Roughly 100 years after Cross founded his ranch, it passed into the hands of his grandson John. And John Cross decided to buck convention. He decided to adopt a holistic method of managing his ranch, working with the ecosystem of the natural grasslands to increase yields without fertilizer. It was a decision that, in the 1980s, was “really uncommon and quite controversial,” he admits. It wasn’t his only quirky decision. In the 1990s, he built an entirely “off-the-grid” house, powering it largely with wind and solar. (Twenty years later, he gave in and ran electric power. Relying completely on renewables “was a pain in the ass,” he admits, especially in winter.)

Today John Cross believes the land has a place to play in a new energy transition. He advocates using offsets to reinvest in Alberta’s ecosystem, and understanding nature’s role as a carbon sink. “I think that’s where oil and gas and land ownership in Alberta can benefit each other,” he says.

Back on the highway, the mayor says he is buoyed by new ideas emerging, and he’s hopeful that Albertans are ready at last to find the common ground necessary to deliver on the urgent billboard directive.

“I think you’ve seen government shift just very recently from ‘all in’ on oil and gas to a more balanced view,” says Nenshi, as he rolls along through the prairie on the road to Edmonton. “Everyone wants jobs. Everyone wants a sustainable economy. And these are the sorts of things that should transcend partisanship.” It’s time to back up the billboard with action.

*****

An oil region by the numbers

26%

Portion of Alberta’s GDP last year connected to the oil and gas industry, including mining. The sector’s indirect impact on the province’s economy is even larger

$3 billion

Projected shortfall in resource revenues in Alberta’s revised budget this year, largely because of lower oil prices

67,000

Estimated number of jobs that could be created in Alberta by 2030 in a green-energy transition according to the nonprofit Pembina Institute

96%

Portion of Alberta’s oil exports that go to the U.S.

$45 per barrel

Price of crude at which most oil-sands production breaks even, according to industry consultants. For some projects, the break-even price can be as high as $85

A version of this article appears in the October 2020 issue of Fortune with the headline “After the oil rush.”