虽然在疫苗方面获得积极进展,但新冠疫情远未结束。

不过在经济方面有持续改善迹象。随着春夏两季各州陆续放松封锁,美国经济从历史上的最严重收缩转变为复苏最迅速的经济体之一。事实上,4月美国失业率达到14.7%的高点后,到10月已经降至6.9%。

然而,美国经济并未走出困境。随着受疫情影响严重的企业现金耗尽,越来越多的企业濒临倒闭。而且在疲软的劳动力市场中,在职者很难加薪,数百万失业者找工作也很艰难。经济是在恢复,但并不是所有人都能够感觉到。

为了帮助《财富》杂志读者更深入了解经济形势和发展方向,下面来分析危机期间一直跟踪的8项经济指标:

疫情中的封锁对GDP造成了巨大损失。今年一季度,GDP年度增长率下降5%,二季度GDP下降31.4%,创下历史纪录。在此期间,全球各地的经济学家陷入恐慌,担心美国以及其他地区是否面临新一轮经济萧条。

在各州开始放松封锁后,美国经济从大幅收缩迅速转到高速增长。根据美国经济分析局(U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis)公布的经济数据,三季度美国GDP同比增长33%。

但GDP总量仍然在下降。前两个季度,美国的年化GDP从21.8万亿美元下降到19.5万亿美元。三季度回升到约21.2万亿美元。预计2021年某个时点将全面反弹。

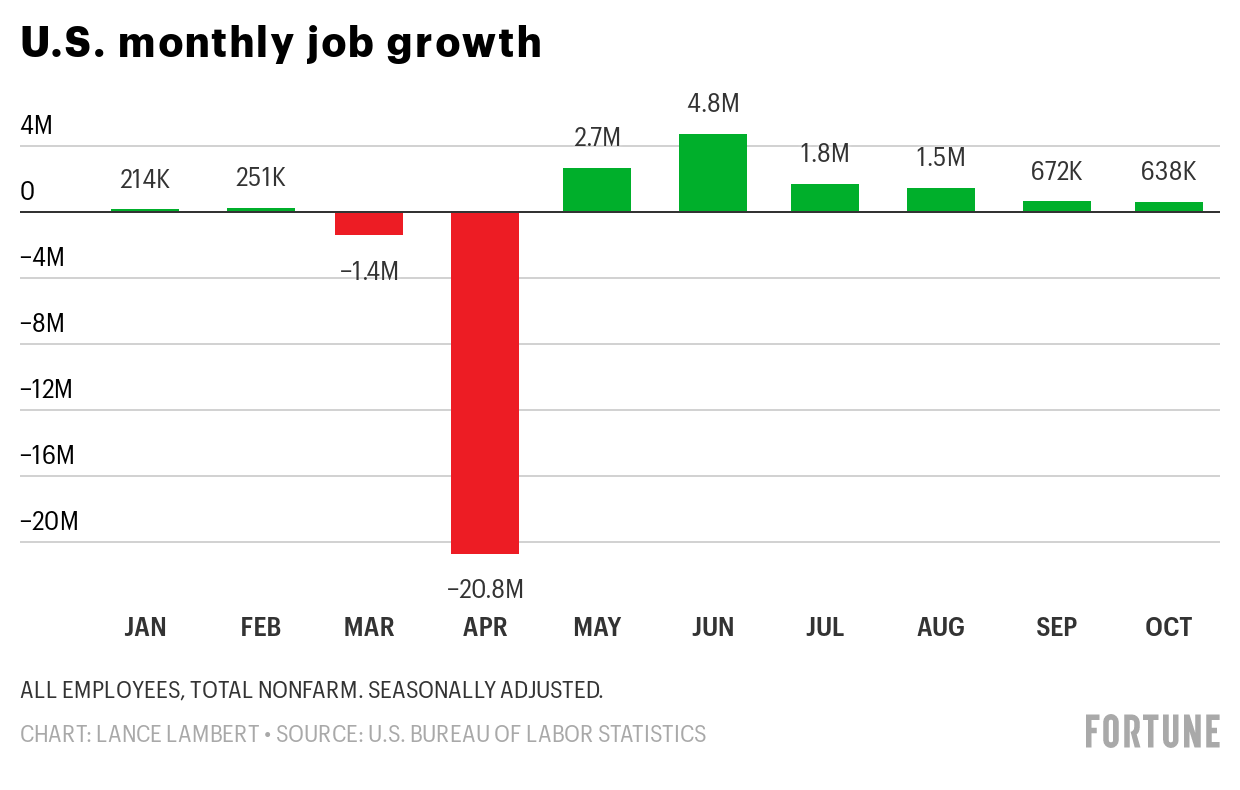

尽管美国GDP接近V型复苏,就业情况却并非如此。10月美国新增就业63.8万。如果按照该速度继续,需要16个月的时间,也就是到2022年才可以恢复疫情经济衰退期间失去的工作岗位。但这还不是最糟的消息。多数经济学家预计就业速度将进一步放缓,也就是说可能要等到2023年或更久之后就业才能够全面复苏。

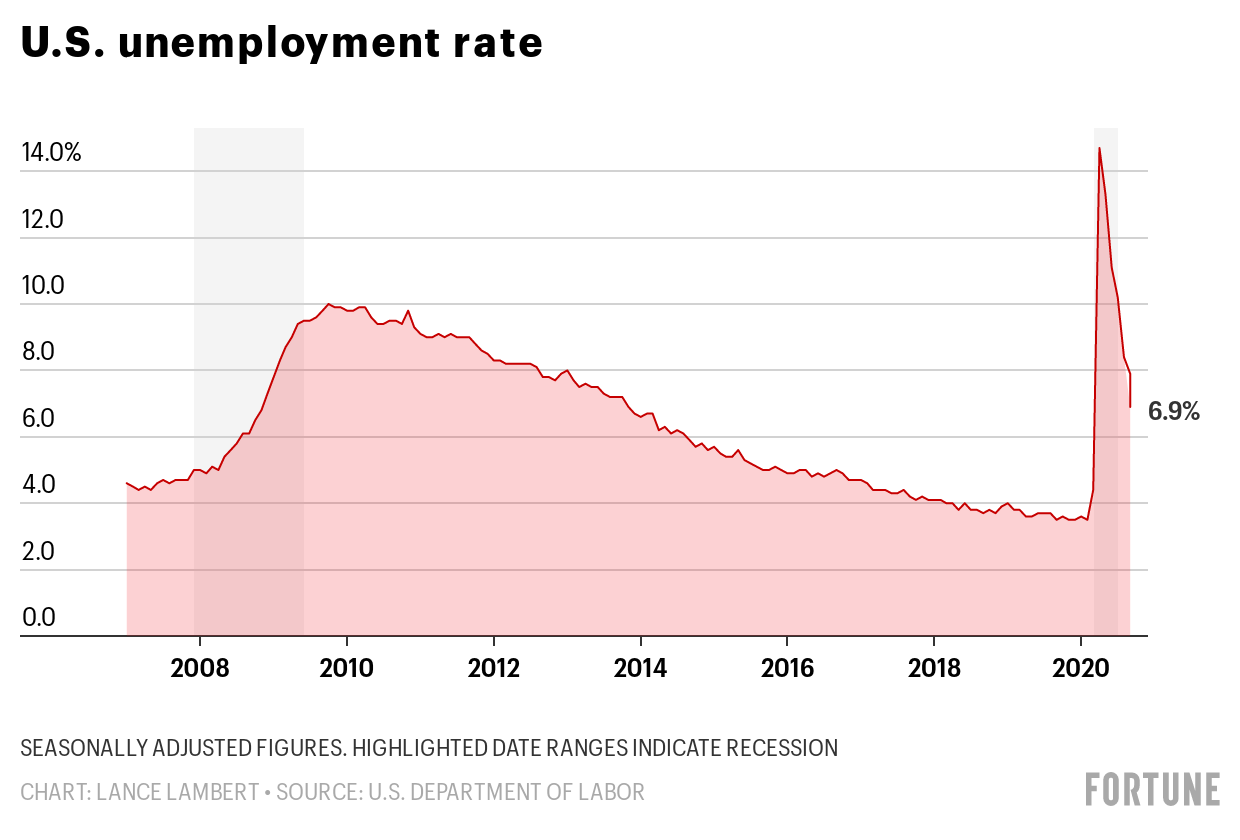

3月停产之后,美国经济遭逢史上最严重收缩。失业率从2月的3.5%跃升至4月的14.7%,为1940年以来最高。

此后的复苏比很多经济学家预期中更快。截至10月的失业率为6.9%,比起5月国会预算办公室(Congressional Budget Office)预测2021年年底9.5%的失业率好很多。

在大衰退期间,2009年10月的失业率达到10%的峰值。直到2013年11月,失业率才回落到6.9%。因此,以近期历史经验来看,复苏相当迅速。

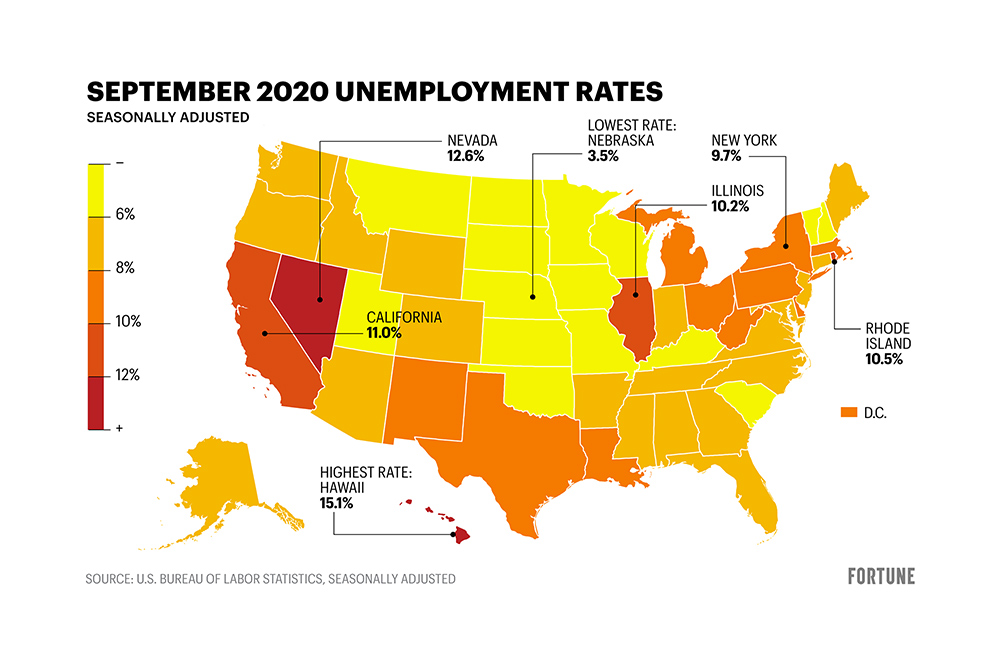

不过本轮经济复苏绝非一帆风顺。9月内布拉斯加州失业率为3.5%,内华达州失业率达12.6%。

为何差异如此明显?很大程度上取决于各州经济中岗位构成。可以看看旅游业重振内华达州的情况,失业率从2月的3.8%飙升至4月的30.1%。虽然后来内华达州的失业率回调至12.6%,但在拉斯维加斯旅游业恢复之前很难彻底扭转。而在疫情控制住之前,旅游业想恢复几乎不可能。

与此同时,爱荷华和内布拉斯加等农业经济比例较高的州的复苏速度更快。

失业率持续下降标志着经济从衰退走向增长,但失业率数据严重低估了失业情况。主要原因是美国劳工统计局(Bureau of Labor Statistics)计算官方失业率的方式。只有失业后正在找新工作的人才能算失业者。如果失业者不找工作,就不会算在劳动力市场之内。(失业率计算方法是美国失业人数除以劳动力总人数。)

疫情期间就属于此类情况,数百万美国人失业后重新找工作之前,选择在家等疫情过去,等居家隔离令解除,要么就在家陪着孩子上网课。总体而言,劳动力从2月的1.645亿下降到4月的1.565亿。此后回升到1.609亿人,但还是减少了360万人。

据《财富》杂志估算,如果360万尚未重返劳动力市场的失业人口也统计在内,那么10月《财富》杂志认为的“实际”失业率应该为8.9%,远高于劳工统计局公布的6.9%官方失业率。

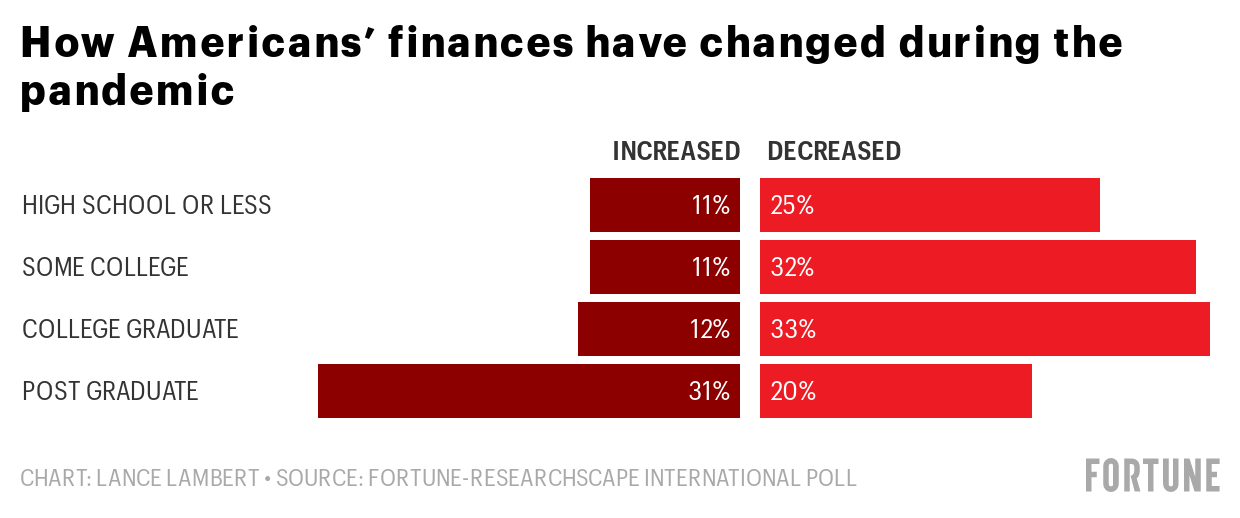

疫情期间,美国人财务状况如何变化。图片来源:《财富》-Researchscape International调查

一部分美国人努力维持生计之际,另一些躲过裁员的人财务状况则更好,主要是因为省下了通勤、外出就餐或旅游的钱。10月3日至10月19日,《财富》杂志与Researchscape International对3133名美国成年人进行了调查,结果显示在拥有研究生学位的美国人中,31%的人表示财务状况有所改善,而高中及以下学历的人当中只有11%表示经济状况更好,而这类人群从事受疫情影响最严重领域工作的可能性更大。

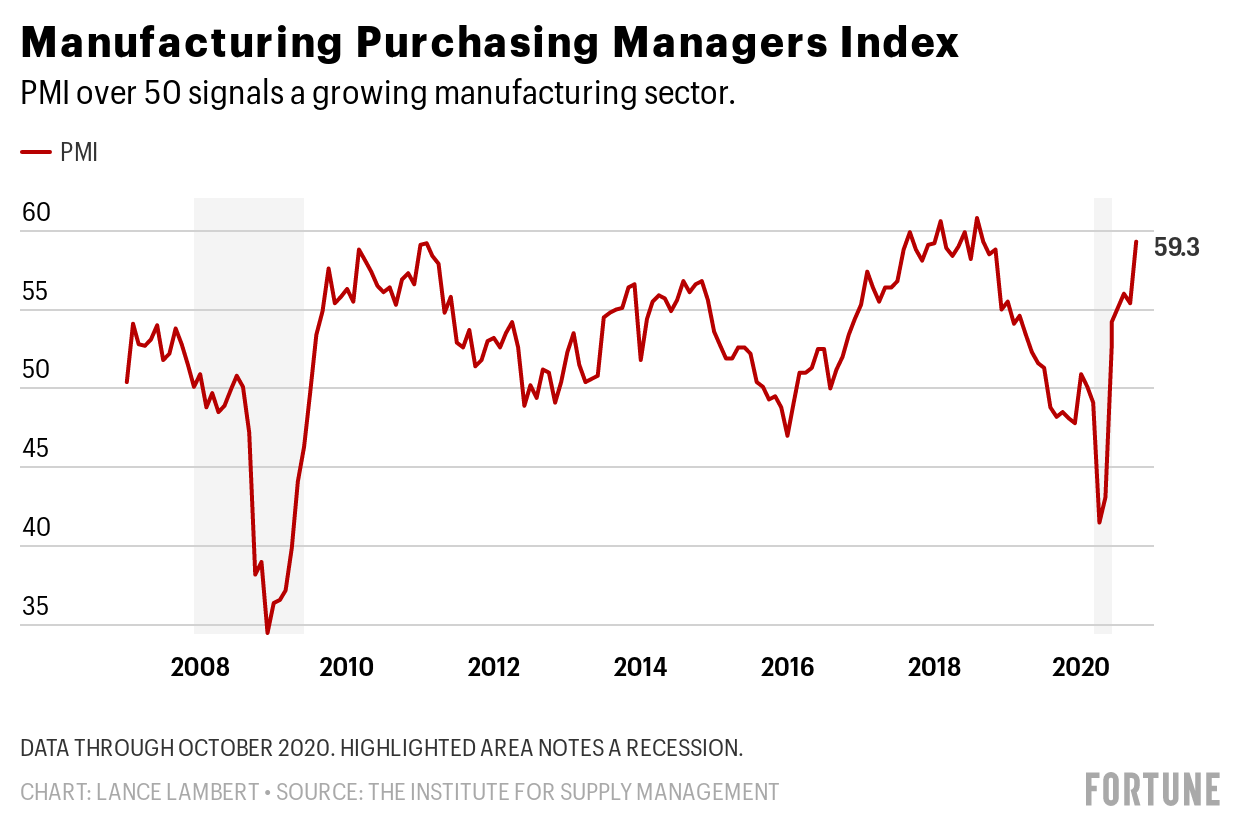

之前的大衰退曾经重创制造业,但本次制造业却是亮点之一。美国供应管理协会(Institute for Supply Management)公布10月的采购经理人指数(PMI)为59.3,高于4月的低点41.5。PMI低于50意味着制造业正在收缩,PMI超过50则意味着制造业已经连续五个月实现增长。

在春季停工期间,多家工厂关停,导致普遍短缺。而在不久的将来,制造商将忙着补上需求。

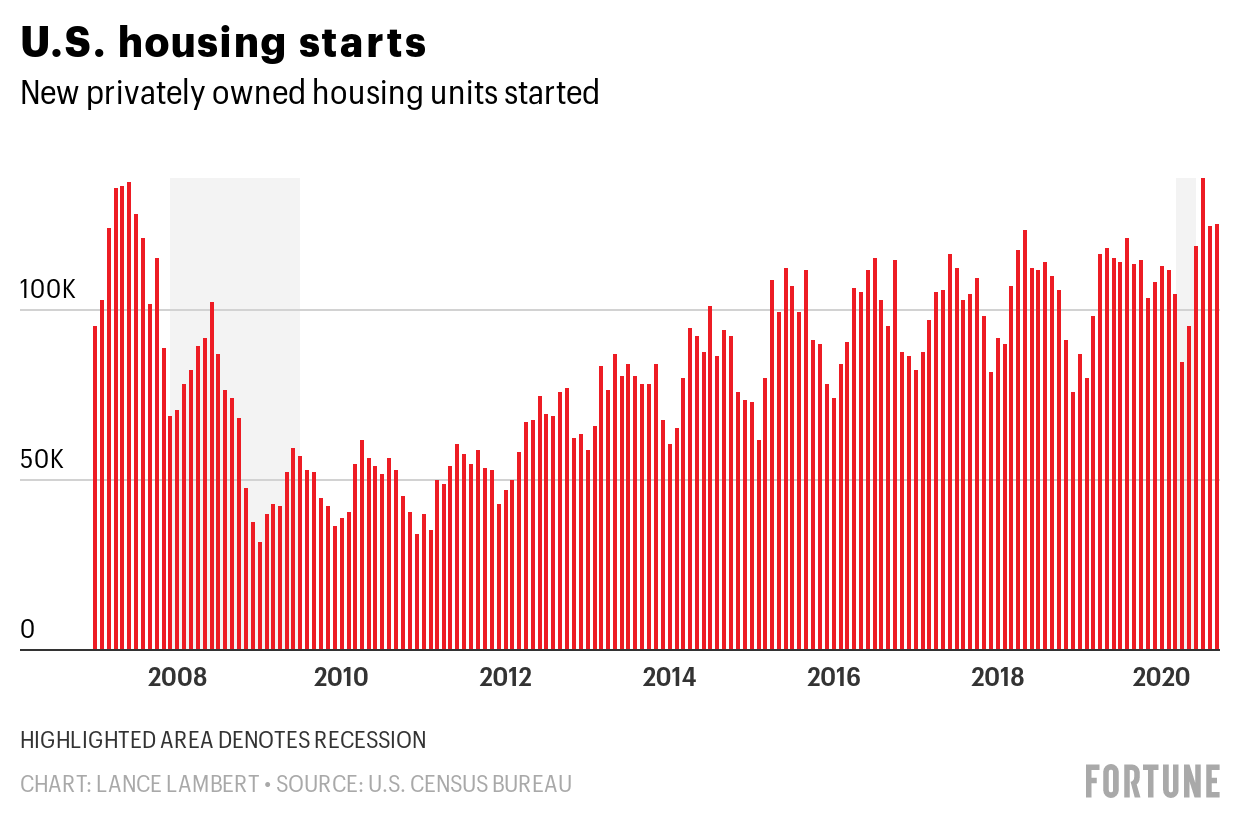

地产开发商上次如此忙碌还是乔治·W·布什执掌白宫的时候。总体计算,9月建筑工人开始建造140万套新房子,比去年同期增长了11%。由于地产开发反弹太强劲,导致木材短缺状况加剧。一段时间里,木材价格飙升了130%。

为何房市如此稳健?首先,利率下跌、股市创纪录上涨以及富裕的城市居民购买第二套住房,都可以提振房地产行业。这也与人口统计学相关。千禧一代出生人数最多的年份是1989年至1993年,随着这群人陆续到30岁,也就是购房高峰期,推动了房地产五年繁荣。千禧一代涌入推动了房地产价格上涨。

总之,通过经济数据能够看到经济发展状况。而从当前数据可以看出什么?其实是两次复苏的故事,其中一些人、某些职业和地区迅速恢复(或者从一开始就不是很痛苦),另一些人还在艰难跋涉,努力挽回疫情中失去的财富。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

虽然在疫苗方面获得积极进展,但新冠疫情远未结束。

不过在经济方面有持续改善迹象。随着春夏两季各州陆续放松封锁,美国经济从历史上的最严重收缩转变为复苏最迅速的经济体之一。事实上,4月美国失业率达到14.7%的高点后,到10月已经降至6.9%。

然而,美国经济并未走出困境。随着受疫情影响严重的企业现金耗尽,越来越多的企业濒临倒闭。而且在疲软的劳动力市场中,在职者很难加薪,数百万失业者找工作也很艰难。经济是在恢复,但并不是所有人都能够感觉到。

为了帮助《财富》杂志读者更深入了解经济形势和发展方向,下面来分析危机期间一直跟踪的8项经济指标:

疫情中的封锁对GDP造成了巨大损失。今年一季度,GDP年度增长率下降5%,二季度GDP下降31.4%,创下历史纪录。在此期间,全球各地的经济学家陷入恐慌,担心美国以及其他地区是否面临新一轮经济萧条。

在各州开始放松封锁后,美国经济从大幅收缩迅速转到高速增长。根据美国经济分析局(U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis)公布的经济数据,三季度美国GDP同比增长33%。

但GDP总量仍然在下降。前两个季度,美国的年化GDP从21.8万亿美元下降到19.5万亿美元。三季度回升到约21.2万亿美元。预计2021年某个时点将全面反弹。

尽管美国GDP接近V型复苏,就业情况却并非如此。10月美国新增就业63.8万。如果按照该速度继续,需要16个月的时间,也就是到2022年才可以恢复疫情经济衰退期间失去的工作岗位。但这还不是最糟的消息。多数经济学家预计就业速度将进一步放缓,也就是说可能要等到2023年或更久之后就业才能够全面复苏。

3月停产之后,美国经济遭逢史上最严重收缩。失业率从2月的3.5%跃升至4月的14.7%,为1940年以来最高。

此后的复苏比很多经济学家预期中更快。截至10月的失业率为6.9%,比起5月国会预算办公室(Congressional Budget Office)预测2021年年底9.5%的失业率好很多。

在大衰退期间,2009年10月的失业率达到10%的峰值。直到2013年11月,失业率才回落到6.9%。因此,以近期历史经验来看,复苏相当迅速。

不过本轮经济复苏绝非一帆风顺。9月内布拉斯加州失业率为3.5%,内华达州失业率达12.6%。

为何差异如此明显?很大程度上取决于各州经济中岗位构成。可以看看旅游业重振内华达州的情况,失业率从2月的3.8%飙升至4月的30.1%。虽然后来内华达州的失业率回调至12.6%,但在拉斯维加斯旅游业恢复之前很难彻底扭转。而在疫情控制住之前,旅游业想恢复几乎不可能。

与此同时,爱荷华和内布拉斯加等农业经济比例较高的州的复苏速度更快。

失业率持续下降标志着经济从衰退走向增长,但失业率数据严重低估了失业情况。主要原因是美国劳工统计局(Bureau of Labor Statistics)计算官方失业率的方式。只有失业后正在找新工作的人才能算失业者。如果失业者不找工作,就不会算在劳动力市场之内。(失业率计算方法是美国失业人数除以劳动力总人数。)

疫情期间就属于此类情况,数百万美国人失业后重新找工作之前,选择在家等疫情过去,等居家隔离令解除,要么就在家陪着孩子上网课。总体而言,劳动力从2月的1.645亿下降到4月的1.565亿。此后回升到1.609亿人,但还是减少了360万人。

据《财富》杂志估算,如果360万尚未重返劳动力市场的失业人口也统计在内,那么10月《财富》杂志认为的“实际”失业率应该为8.9%,远高于劳工统计局公布的6.9%官方失业率。

一部分美国人努力维持生计之际,另一些躲过裁员的人财务状况则更好,主要是因为省下了通勤、外出就餐或旅游的钱。10月3日至10月19日,《财富》杂志与Researchscape International对3133名美国成年人进行了调查,结果显示在拥有研究生学位的美国人中,31%的人表示财务状况有所改善,而高中及以下学历的人当中只有11%表示经济状况更好,而这类人群从事受疫情影响最严重领域工作的可能性更大。

之前的大衰退曾经重创制造业,但本次制造业却是亮点之一。美国供应管理协会(Institute for Supply Management)公布10月的采购经理人指数(PMI)为59.3,高于4月的低点41.5。PMI低于50意味着制造业正在收缩,PMI超过50则意味着制造业已经连续五个月实现增长。

在春季停工期间,多家工厂关停,导致普遍短缺。而在不久的将来,制造商将忙着补上需求。

地产开发商上次如此忙碌还是乔治·W·布什执掌白宫的时候。总体计算,9月建筑工人开始建造140万套新房子,比去年同期增长了11%。由于地产开发反弹太强劲,导致木材短缺状况加剧。一段时间里,木材价格飙升了130%。

为何房市如此稳健?首先,利率下跌、股市创纪录上涨以及富裕的城市居民购买第二套住房,都可以提振房地产行业。这也与人口统计学相关。千禧一代出生人数最多的年份是1989年至1993年,随着这群人陆续到30岁,也就是购房高峰期,推动了房地产五年繁荣。千禧一代涌入推动了房地产价格上涨。

总之,通过经济数据能够看到经济发展状况。而从当前数据可以看出什么?其实是两次复苏的故事,其中一些人、某些职业和地区迅速恢复(或者从一开始就不是很痛苦),另一些人还在艰难跋涉,努力挽回疫情中失去的财富。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

Even with positive developments on the vaccine front, the pandemic is far from over.

But on the economic front, we’re continuing to see improvement. As states eased lockdown restrictions in the spring and summer, the economy switched from the worst contraction in history to one of the fastest recoveries. Indeed, the unemployment rate that hit a peak of 14.7% in April has since come down to 6.9% as of October.

That said, we aren’t out of the woods yet. More business failures are on the way as companies hardest hit by the pandemic run out of cash. Not to mention the weak labor market makes it hard for the employed to get raises and the millions of unemployed Americans to find a paycheck. We’re in recovery, but not all of us are feeling it.

To give Fortune readers a better understanding of where the economy is and where it’s heading, here’s a look at eight economic measurements we’ve been tracking throughout the crisis:

The lockdowns took a massive toll on gross domestic product. In the first quarter, GDP declined 5% on an annualized basis, followed by a record 31.4% annualized GDP decline in the second quarter. During that period economists around the world were in a panic and questioning if the United States—as well as the rest of the world—was on the cusp of an economic depression.

Once states began to ease lockdown restrictions, the U.S. economy sprung from deep contraction to high growth. In the third quarter, from July to September, GDP climbed 33.1% on an annualized basis, according to data released by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

But GDP is still down. Over the course of the first two quarters, annualized U.S. GDP fell from $21.8 trillion to $19.5 trillion. In the third quarter that swung back up to about $21.2 trillion. It’s expected to fully rebound sometime in 2021.

While GDP is seeing something closer to a V-shaped recovery—bouncing back nearly as fast as it fell—that isn’t the case for U.S. employment. The U.S. added 638,000 jobs in October. If that pace were to continue, it would take over 16 months—into 2022—to recover all the jobs lost during the COVID-19 recession. And that’s not even the bad news. Most economists actually expect that pace of hiring to slow further, meaning a full employment recovery could take until 2023 or longer.

The economic contraction following the March shutdowns was the sharpest in U.S. history: The jobless rate jumped from 3.5% in February—a 50-year low—to 14.7% in April——the highest level since 1940.

We’ve since shifted into a recovery that is moving faster than many economists expected. The unemployment rate stands at 6.9% as of October. That beats the timeline the Congressional Budget Office projected in May, when it forecasted a 9.5% unemployment rate at the end of 2021.

During the Great Recession era, the unemployment rate peaked at 10% in October 2009. And it didn’t make it back down to 6.9% until November 2013. So by recent historical standards, this recovery is moving at a swift pace.

But this economic recovery is anything but even. While the unemployment rate in September in Nebraska sits at 3.5%, Nevada has a jobless rate of 12.6%.

How did these economies get so divided? A lot of it boils down to what types of jobs make up each state’s economy. Look no further than tourism-heavy Nevada which saw its jobless rate soar from 3.8% in February to a staggering 30.1% in April. While Nevada has since improved to a 12.6% jobless rate, it will struggle to fully recover until the Las Vegas tourism business has returned to normal—something that is unlikely to happen until the pandemic is under control.

Meanwhile, rural agriculture-heavy economies like Iowa and Nebraska are recovering at a much faster clip.

While the sustained drop in the unemployment rate signals an economy moving from recession to growth, it’s also severely undercounting joblessness. It boils down to how the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) calculates the official unemployment rate: Only out-of-work Americans who are searching for new positions are categorized as unemployed. If the jobless aren’t searching, they get thrown out of the civilian labor force altogether. (The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployedAmericans by the civilian labor force count).

That’s been the case during the pandemic, with millions of jobless Americans choosing to wait out the virus and stay-at-home order before starting their job search, or to stay home with their kids who have not resumed in-person learning. Overall the civilian labor force declined from 164.5 million in February to 156.5 million in April. It has since climbed up to 160.9 million—but it’s still down 3.6 million.

If the 3.6 million jobless Americans who’ve yet to return to the workforce were to be included in the unemployment rate—what Fortune considers the “real” unemployment rate—it would sit at 8.9% in October, Fortunecalculates. That’s well above the 6.9% official unemployment rate calculated by the BLS.

While some Americans are struggling to make ends meet, others who have escaped layoffs are actually better off financially as they save money that would have been spent on commuting, eating out, or traveling. And that divide is happening along class lines: Among Americans with a postgraduate degree, 31% say their finances have improved, finds a Fortune–Researchscape International poll of 3,133 U.S. adults conducted between Oct. 3 and Oct. 19. While only 11% of U.S. adults with a high school degree or less—who are more likely to work in fields hardest hit by the pandemic—say they’re financially better off now.

While the Great Recession hammered manufacturing, this time around the sector is among our bright spots. The Institute for Supply Management’s Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) came in at 59.3 in October, up from its 41.5 bottom in April. A PMI below 50 signals a contracting manufacturing sector, while a rate over 50 signals growth—something we’ve achieved for five consecutive months.

The spring lockdowns closed numerous factories, which led to widespread shortages. In the immediate future, manufacturers are busy making up for those shortfalls.

The last time homebuilders were this busy George W. Bush was in the White House. In total, construction crews started working on 1.4 million new homes in September, up 11% from a year prior. The rebound in homebuilding is so strong that it has worsened the national lumber shortage; for a period lumber prices spiked 130%.

How can housing be so robust? For starters the sector has been helped by falling interest rates, a record stock market, and wealthy city dwellers buying up second homes. But it’s also demographics. The biggest years for millennial births ranged from 1989 to 1993. And we’re currently amid the five-year period when all these young millennials will hit their thirties—the peak years for homebuying. That rush of millennials into the market is causing real estate to push upward.

Overall, economic data is most helpful to piece together a story about the economy. What’s this one telling us? It’s truly a tale of two recoveries whereby some people, professions, and geographic areas have recovered swiftly (or never felt too much pain in the first place), while others are mired in a long slog, trying to recapture the gains so swiftly lost to a deadly pandemic.