南非人。巴西人。英国“肯特”。

这些听起来没有什么特别,有点像某种特定发型的名字。但正如病毒追踪者所知,这些都是新冠病毒变异毒株的简称。变异病毒的传染性更强,其中,英国变异病毒株可能更致命,迫使世界各国政府加紧旅行限制,有些国家还宣布了新的封锁令。

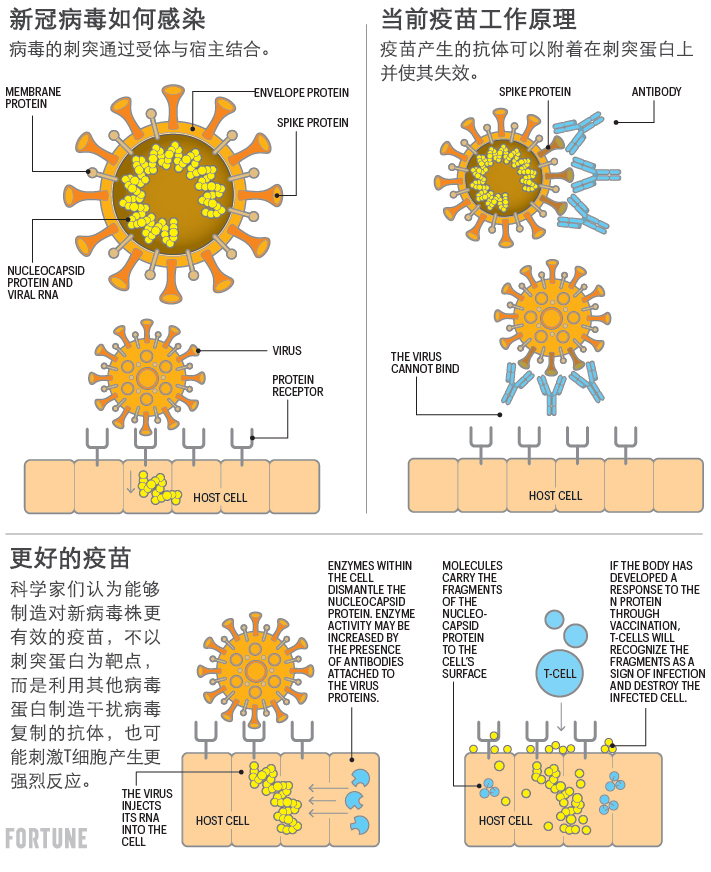

新型变异病毒也给第一批新冠疫苗带来了问题。目前几乎所有获批的疫苗都是针对冠状病毒的刺突蛋白。蛋白突变会降低疫苗的有效性,甚至导致免疫失败。

现在疫苗生产商和政府提出的解决方案是,开始准备新版疫苗,促使免疫系统产生针对新病毒刺突蛋白的抗体。

但如果病毒不断变异,就可能陷入永恒的猫捉老鼠游戏。人们总要追赶最新的病毒株,全世界大部分地区每年都要接种加强疫苗。流感病毒基本上就是如此。

而且跟流感病毒一样,研究人员经常有可能误判,从而忽视新出现并迅速传播的变异病毒,是患者再次面临必须住院治疗甚至死亡的风险。

还有别的办法吗?

一些科学家认为有:要么使用更传统的疫苗技术,让人们实际接触到病毒和各种蛋白质;要么用新型信使RNA技术,制造出能够应对当前及未来所有变异病毒的通用疫苗。

为什么变异病毒如此令人担心

首先,多提供一点当前背景,虽然正式命名为B.1.1.7的英国“肯特”病毒的传播性更强,也更致命,但刺突蛋白没有明显改变,已经获批的疫苗可以很好地应对。

然而分别被正式命名为B.1.351和B.1.1.248的南非和巴西变异病毒都会导致现有疫苗效力降低。

牛津大学和制药公司阿斯利康合作疫苗在南非的临床试验数据分析表明,疫苗不能预防B.1.351毒株导致的轻症和普通感染,不过阿斯利康宣称,相信能够预防新冠重症。

实验室也测试了辉瑞和Moderna信使RNA疫苗接种者的血液样本,结果也表明如果抗体要应对变异毒株,抗体量要比应对原始病毒高。但Moderna公司表示,相信自家疫苗可以产生足够抗体,能够预防普通型或重症。

令人担心的是,英国科学家发现B.1.1.7“肯特”病毒一个版本中也包含了跟南非和巴西毒株相同的刺突蛋白突变,即E484K。

如果一个人感染多种病毒,各病毒株的遗传物质混合有可能出现该情况,也可能是同一种突变发生不止一次的结果。

目前大多数获批疫苗均采用相对较新的技术制造,包括信使RNA(mRNA)或改良腺病毒载体。

两种疫苗的思路都是指导人类细胞生产新冠病毒的一种蛋白质,激发免疫反应。然后身体产生抗体,抗体可以附着在蛋白质上使之失效。人们还希望免疫系统其他部分,例如能够杀死受感染细胞的T细胞,根据蛋白识别外来入侵者并将其清除。

新疫苗的另一大优势在于,只要病毒基因组完成测序,并有明显的蛋白质作为靶点,就像新冠病毒一样,疫苗就可以迅速适应新病毒。之所以世界卫生组织宣布发现病毒不到一年后的今天,数百万人中就能够接种多种疫苗,主要就是因为采用了新型疫苗制造方法。

单一蛋白质问题

不过迄今相关技术抗击新冠病毒的一大缺点在于,疫苗只可以指导细胞制造一种病毒蛋白。因此疫苗容易受到特定蛋白质突变影响。

新冠病毒有四个主要的结构蛋白,其中S蛋白(刺突蛋白)最为人所知,还有N蛋白(核衣壳蛋白)、M蛋白(膜蛋白)以及E蛋白(包膜蛋白)。因此,想让疫苗刺激免疫系统,对某些甚至所有蛋白产生反应是存在可能性的。

两种传统疫苗制造技术让人体暴露于各种蛋白中,因为使用了真正的病毒。

其中一种方法是将活病毒“减毒”或削弱,在很难快速繁殖的环境中生长。另一种方法则是将病毒“灭活”,或者用化学方式杀死,然后进行整体注射,或是粉碎后注射。该方法可能比给人注射活病毒疫苗更安全,因为活病毒疫苗存在变成危险病原体的风险。

没有公司考虑新冠活疫苗,灭活疫苗倒是有几家公司研制。

中国公司科兴生产的疫苗就使用灭活病毒,在中国和巴西等地已经有数十万人接种。该公司称,自家的疫苗能够有效抵抗南非变异病毒,但并未公布数据。

在巴西进行的科兴疫苗临床试验表明,这种疫苗在预防重症方面100%有效,但在预防轻症方面几率仅略高于50%。

多价疫苗

与此同时,法国Valneva公司的首席执行官托马斯·林格尔巴克说,正在研制使用完整病毒的灭活疫苗,可能比已经获批的疫苗更具优势。由于使用完整病毒,Valneva疫苗有可能让免疫系统对各种抗原表位出现反应,抗原表位是指免疫系统可以识别的病毒蛋白部分。Valneva还将灭活病毒与辅药结合,辅药是能够增强人体免疫反应的化学物质。

更重要的是,Valneva有生产多价疫苗的经验,所以可能会生产针对新冠的疫苗,所谓多价疫苗是指一次注射中包含多种毒株。

林格尔巴克称公司将努力赶上新冠候选疫苗“第三波”,相信明年春天能够获批提供多价疫苗。(第一波是已获批疫苗,第二波是目前已经进入人体临床试验的疫苗。)

英国政府已经预购了1亿剂Valneva疫苗,其中一些将在苏格兰分公司工厂生产。

“通用”疫苗

还有一种方法可能为通用新冠疫苗带来希望,思路是寻找既可以引起强烈免疫反应,又对新冠病毒繁殖至关重要的抗原表位。如果相关蛋白对病毒的生命周期至关重要,那病毒就无法通过成功突变避开疫苗。

比利时初创公司MyNeo就选择了该方法,利用机器学习,预测病毒哪些抗原表位可以引发强烈的免疫反应。

该公司的首席执行官塞德里克·博格特表示,找到之后会在各种冠状病毒发现的抗原表位里寻找子集。他指出,有些抗原表位不仅在新冠所有变异中都相同,而且在引起非典(SARS)和中东呼吸综合征(MERS)的冠状病毒中,还有感染水貂和蝙蝠的已知冠状病毒中都一样。

水貂和蝙蝠均携带冠状病毒,科学家认为未来病毒可能会传给人类。生物学家称常见蛋白片段“保存完好”,进而推测随着时间推移,相关蛋白不会出现太大变化,因为蛋白正常工作对病毒生存至关重要。

特别令人感兴趣的是,新冠病毒里的N蛋白,主要存在于病毒内部,围绕在病毒遗传密码RNA周围。

业界普遍认为N蛋白在病毒感染细胞后的复制方面起着关键作用。各种冠状病毒里的N蛋白部分非常相似。人类细胞中发现的抗体能够识别N蛋白。

与粘附在刺突蛋白上的抗体不同,此类抗体不能阻止细胞被感染。抗体在细胞内发现N蛋白后会将其分解成碎片,然后在细胞表面展示标记。人的T细胞利用标记来识别被感染的细胞,并把它清除掉。

MyNeo正在与另一家比利时公司eTheRNA合作,公司的业务开发主管麦克·马尔奎恩表示,公司可以制造mRNA疫苗,还发明了一种名叫TriMix的专利辅药,能够显著增强人体T细胞和B细胞对疫苗的反应。MyNeo协助公司选择一组合适的蛋白质,比如N蛋白,与疫苗中的TriMix一起使用。

马尔奎恩认为,公司有望生产对预防未来各种病毒株更有效的疫苗。他介绍说,可能会在一年内进入后期临床试验。

其他科学家持怀疑态度

不过也有人对类似方法持怀疑态度。

新墨西哥州立大学的生物学教授凯瑟琳·汉利研究过登革热病毒疫苗,认为灭活病毒疫苗激发的免疫反应,跟自然感染新冠病毒的反应差别并不大。在感染新冠肺炎的患者中,刺突蛋白似乎是出现免疫反应的主要原因。

马尔奎恩说,如果采用mRNA方法制造疫苗,可能不是什么问题。原因在于,虽然自然感染过程中,对某个特定抗原表位的免疫反应往往占主导地位,但如果身体像注射mRNA疫苗一样,单独遭遇不同的抗原表位,如果再使用辅药,就有可能引发对该特定蛋白质强烈的免疫反应。

纽约康奈尔大学威尔·康奈尔医学院的微生物学和免疫学教授,约翰·摩尔表示,这并不能确定。

他说,虽然人体对新冠病毒出现免疫反应的方式还不是很清楚,但“诸多线索显示,中和抗体才是关键。”他说,T细胞和B细胞反应可能由其他蛋白质触发,可能会起到一定作用,但抗体才是关键,毕竟是抗体激发对刺突蛋白的反应。

“S蛋白是中和抗体的唯一靶点,选择并不多。”他说。

即使摩尔说错了,马尔奎恩也还是承认MyNeo和eTheRNA研制新冠通用疫苗的方法长期来看可能有问题。

虽然理论上保存完好的抗原表位很可能对病毒的生命周期至关重要,因而不太可能成功变异,但实际上可能并非如此。此类蛋白从未经历重大的选择压力。

马尔奎恩表示,一旦注射针对其他蛋白质的疫苗,病毒有可能进化出躲避疫苗的方法。

古老的挑战

在医学史上,制造通用疫苗的失败案例比比皆是。

“很长时间以来,人们研制通用流感疫苗的努力都以失败告终。”汉利说。她说此前尝试过同样的想法,在不同的毒株中寻找保存完好的抗原表位,但迄今为止都失败了。

流感病毒的变异速度远远快于冠状病毒,冠状病毒在复制过程中有一个步骤可以校对复制的基因密码防止出错,从而减缓变异。

“冠状病毒不是流感,所以有可能,但也不确定。”她说。

有些科学家认为,研发新疫苗解决新冠变异病毒的说法为时过早。

“目前还没有达到临界线。”费城儿童医院的传染病专科医师、疫苗教育中心的主任保罗·奥菲特说。

他指出,越过临界线意味着自然感染原始病毒的人,或者注射了获批疫苗的人再次感染新毒株,而且病情严重到需要住院治疗。

他表示,已经接受两剂疫苗的人体内抗体水平很高,这很让人振奋,特别是辉瑞和Moderna的mRNA疫苗,说明抗体很强,即使面对新毒株也能够继续抵御。

他表示,由于冠状病毒变异往往比流感少,如果在未来几个月内,有足够多的人接种疫苗,而且有相当多的人已经感染新冠肺炎,病毒传播则有望下降。只要传播放缓,发生突变的可能性也将减小,新一代疫苗投入使用也就没有什么问题。

摩尔对此表示赞同,他认为届时不一定需要每年强化当前疫苗。

“计划并加以考虑有合理性,不过当前还没有到那一步。”他说。

所有科学家包括研究新一代疫苗的科学家都认为,相较于应付比英国、南非和巴西还要麻烦的病毒变异,关键在于要尽快推动尽可能多的人接种疫苗,从而降低病毒传播。

他们说,如果有人宣称不用全民接种疫苗,年轻人感染后不太可能转为重症,就让病毒在年轻人群里传播,都会变成灾难的导火索。

“耐药病毒只在特定情况下出现,其中之一就是疫苗接种不足。”摩尔说。

他还担心延长两剂之间的时间,英国就是如此(两剂之间等待12周,以便给更多人注射第一剂)。因为辉瑞公司和Moderna的第一剂疫苗免疫应答到底能否持续超过四周,并没有数据支持。

他担心的是,如果病毒发现宿主有某种免疫反应,又无法完全消灭病毒并阻止其复制,就会对病原体施加选择压力,从而出现成功突变。

疫苗接种不足也是流感流行的原因之一。汉利指出,尽管每年流感导致超过5万美国人死亡,美国成人只有不到一半接种流感疫苗。

“大多数公共卫生项目在真正成功之前,都是其自身成功的牺牲品。”她说。“所以根除病原体才如此艰难。”(财富中文网)

译者:夏林

南非人。巴西人。英国“肯特”。

这些听起来没有什么特别,有点像某种特定发型的名字。但正如病毒追踪者所知,这些都是新冠病毒变异毒株的简称。变异病毒的传染性更强,其中,英国变异病毒株可能更致命,迫使世界各国政府加紧旅行限制,有些国家还宣布了新的封锁令。

新型变异病毒也给第一批新冠疫苗带来了问题。目前几乎所有获批的疫苗都是针对冠状病毒的刺突蛋白。蛋白突变会降低疫苗的有效性,甚至导致免疫失败。

现在疫苗生产商和政府提出的解决方案是,开始准备新版疫苗,促使免疫系统产生针对新病毒刺突蛋白的抗体。

但如果病毒不断变异,就可能陷入永恒的猫捉老鼠游戏。人们总要追赶最新的病毒株,全世界大部分地区每年都要接种加强疫苗。流感病毒基本上就是如此。

而且跟流感病毒一样,研究人员经常有可能误判,从而忽视新出现并迅速传播的变异病毒,是患者再次面临必须住院治疗甚至死亡的风险。

还有别的办法吗?

一些科学家认为有:要么使用更传统的疫苗技术,让人们实际接触到病毒和各种蛋白质;要么用新型信使RNA技术,制造出能够应对当前及未来所有变异病毒的通用疫苗。

为什么变异病毒如此令人担心

首先,多提供一点当前背景,虽然正式命名为B.1.1.7的英国“肯特”病毒的传播性更强,也更致命,但刺突蛋白没有明显改变,已经获批的疫苗可以很好地应对。

然而分别被正式命名为B.1.351和B.1.1.248的南非和巴西变异病毒都会导致现有疫苗效力降低。

牛津大学和制药公司阿斯利康合作疫苗在南非的临床试验数据分析表明,疫苗不能预防B.1.351毒株导致的轻症和普通感染,不过阿斯利康宣称,相信能够预防新冠重症。

实验室也测试了辉瑞和Moderna信使RNA疫苗接种者的血液样本,结果也表明如果抗体要应对变异毒株,抗体量要比应对原始病毒高。但Moderna公司表示,相信自家疫苗可以产生足够抗体,能够预防普通型或重症。

令人担心的是,英国科学家发现B.1.1.7“肯特”病毒一个版本中也包含了跟南非和巴西毒株相同的刺突蛋白突变,即E484K。

如果一个人感染多种病毒,各病毒株的遗传物质混合有可能出现该情况,也可能是同一种突变发生不止一次的结果。

目前大多数获批疫苗均采用相对较新的技术制造,包括信使RNA(mRNA)或改良腺病毒载体。

两种疫苗的思路都是指导人类细胞生产新冠病毒的一种蛋白质,激发免疫反应。然后身体产生抗体,抗体可以附着在蛋白质上使之失效。人们还希望免疫系统其他部分,例如能够杀死受感染细胞的T细胞,根据蛋白识别外来入侵者并将其清除。

与传统疫苗制造方法相比,新方法的巨大优势是非常安全,因此研究疫苗的研究人员合理确信疫苗不会引发严重副作用,这一想法在随后的人体临床试验中也得到了证实。

新疫苗的另一大优势在于,只要病毒基因组完成测序,并有明显的蛋白质作为靶点,就像新冠病毒一样,疫苗就可以迅速适应新病毒。之所以世界卫生组织宣布发现病毒不到一年后的今天,数百万人中就能够接种多种疫苗,主要就是因为采用了新型疫苗制造方法。

单一蛋白质问题

不过迄今相关技术抗击新冠病毒的一大缺点在于,疫苗只可以指导细胞制造一种病毒蛋白。因此疫苗容易受到特定蛋白质突变影响。

新冠病毒有四个主要的结构蛋白,其中S蛋白(刺突蛋白)最为人所知,还有N蛋白(核衣壳蛋白)、M蛋白(膜蛋白)以及E蛋白(包膜蛋白)。因此,想让疫苗刺激免疫系统,对某些甚至所有蛋白产生反应是存在可能性的。

两种传统疫苗制造技术让人体暴露于各种蛋白中,因为使用了真正的病毒。

其中一种方法是将活病毒“减毒”或削弱,在很难快速繁殖的环境中生长。另一种方法则是将病毒“灭活”,或者用化学方式杀死,然后进行整体注射,或是粉碎后注射。该方法可能比给人注射活病毒疫苗更安全,因为活病毒疫苗存在变成危险病原体的风险。

没有公司考虑新冠活疫苗,灭活疫苗倒是有几家公司研制。

中国公司科兴生产的疫苗就使用灭活病毒,在中国和巴西等地已经有数十万人接种。该公司称,自家的疫苗能够有效抵抗南非变异病毒,但并未公布数据。

在巴西进行的科兴疫苗临床试验表明,这种疫苗在预防重症方面100%有效,但在预防轻症方面几率仅略高于50%。

多价疫苗

与此同时,法国Valneva公司的首席执行官托马斯·林格尔巴克说,正在研制使用完整病毒的灭活疫苗,可能比已经获批的疫苗更具优势。由于使用完整病毒,Valneva疫苗有可能让免疫系统对各种抗原表位出现反应,抗原表位是指免疫系统可以识别的病毒蛋白部分。Valneva还将灭活病毒与辅药结合,辅药是能够增强人体免疫反应的化学物质。

更重要的是,Valneva有生产多价疫苗的经验,所以可能会生产针对新冠的疫苗,所谓多价疫苗是指一次注射中包含多种毒株。

林格尔巴克称公司将努力赶上新冠候选疫苗“第三波”,相信明年春天能够获批提供多价疫苗。(第一波是已获批疫苗,第二波是目前已经进入人体临床试验的疫苗。)

英国政府已经预购了1亿剂Valneva疫苗,其中一些将在苏格兰分公司工厂生产。

“通用”疫苗

还有一种方法可能为通用新冠疫苗带来希望,思路是寻找既可以引起强烈免疫反应,又对新冠病毒繁殖至关重要的抗原表位。如果相关蛋白对病毒的生命周期至关重要,那病毒就无法通过成功突变避开疫苗。

比利时初创公司MyNeo就选择了该方法,利用机器学习,预测病毒哪些抗原表位可以引发强烈的免疫反应。

该公司的首席执行官塞德里克·博格特表示,找到之后会在各种冠状病毒发现的抗原表位里寻找子集。他指出,有些抗原表位不仅在新冠所有变异中都相同,而且在引起非典(SARS)和中东呼吸综合征(MERS)的冠状病毒中,还有感染水貂和蝙蝠的已知冠状病毒中都一样。

水貂和蝙蝠均携带冠状病毒,科学家认为未来病毒可能会传给人类。生物学家称常见蛋白片段“保存完好”,进而推测随着时间推移,相关蛋白不会出现太大变化,因为蛋白正常工作对病毒生存至关重要。

特别令人感兴趣的是,新冠病毒里的N蛋白,主要存在于病毒内部,围绕在病毒遗传密码RNA周围。

业界普遍认为N蛋白在病毒感染细胞后的复制方面起着关键作用。各种冠状病毒里的N蛋白部分非常相似。人类细胞中发现的抗体能够识别N蛋白。

与粘附在刺突蛋白上的抗体不同,此类抗体不能阻止细胞被感染。抗体在细胞内发现N蛋白后会将其分解成碎片,然后在细胞表面展示标记。人的T细胞利用标记来识别被感染的细胞,并把它清除掉。

MyNeo正在与另一家比利时公司eTheRNA合作,公司的业务开发主管麦克·马尔奎恩表示,公司可以制造mRNA疫苗,还发明了一种名叫TriMix的专利辅药,能够显著增强人体T细胞和B细胞对疫苗的反应。MyNeo协助公司选择一组合适的蛋白质,比如N蛋白,与疫苗中的TriMix一起使用。

马尔奎恩认为,公司有望生产对预防未来各种病毒株更有效的疫苗。他介绍说,可能会在一年内进入后期临床试验。

其他科学家持怀疑态度

不过也有人对类似方法持怀疑态度。

新墨西哥州立大学的生物学教授凯瑟琳·汉利研究过登革热病毒疫苗,认为灭活病毒疫苗激发的免疫反应,跟自然感染新冠病毒的反应差别并不大。在感染新冠肺炎的患者中,刺突蛋白似乎是出现免疫反应的主要原因。

马尔奎恩说,如果采用mRNA方法制造疫苗,可能不是什么问题。原因在于,虽然自然感染过程中,对某个特定抗原表位的免疫反应往往占主导地位,但如果身体像注射mRNA疫苗一样,单独遭遇不同的抗原表位,如果再使用辅药,就有可能引发对该特定蛋白质强烈的免疫反应。

纽约康奈尔大学威尔·康奈尔医学院的微生物学和免疫学教授,约翰·摩尔表示,这并不能确定。

他说,虽然人体对新冠病毒出现免疫反应的方式还不是很清楚,但“诸多线索显示,中和抗体才是关键。”他说,T细胞和B细胞反应可能由其他蛋白质触发,可能会起到一定作用,但抗体才是关键,毕竟是抗体激发对刺突蛋白的反应。

“S蛋白是中和抗体的唯一靶点,选择并不多。”他说。

即使摩尔说错了,马尔奎恩也还是承认MyNeo和eTheRNA研制新冠通用疫苗的方法长期来看可能有问题。

虽然理论上保存完好的抗原表位很可能对病毒的生命周期至关重要,因而不太可能成功变异,但实际上可能并非如此。此类蛋白从未经历重大的选择压力。

马尔奎恩表示,一旦注射针对其他蛋白质的疫苗,病毒有可能进化出躲避疫苗的方法。

古老的挑战

在医学史上,制造通用疫苗的失败案例比比皆是。

“很长时间以来,人们研制通用流感疫苗的努力都以失败告终。”汉利说。她说此前尝试过同样的想法,在不同的毒株中寻找保存完好的抗原表位,但迄今为止都失败了。

流感病毒的变异速度远远快于冠状病毒,冠状病毒在复制过程中有一个步骤可以校对复制的基因密码防止出错,从而减缓变异。

“冠状病毒不是流感,所以有可能,但也不确定。”她说。

有些科学家认为,研发新疫苗解决新冠变异病毒的说法为时过早。

“目前还没有达到临界线。”费城儿童医院的传染病专科医师、疫苗教育中心的主任保罗·奥菲特说。

他指出,越过临界线意味着自然感染原始病毒的人,或者注射了获批疫苗的人再次感染新毒株,而且病情严重到需要住院治疗。

他表示,已经接受两剂疫苗的人体内抗体水平很高,这很让人振奋,特别是辉瑞和Moderna的mRNA疫苗,说明抗体很强,即使面对新毒株也能够继续抵御。

他表示,由于冠状病毒变异往往比流感少,如果在未来几个月内,有足够多的人接种疫苗,而且有相当多的人已经感染新冠肺炎,病毒传播则有望下降。只要传播放缓,发生突变的可能性也将减小,新一代疫苗投入使用也就没有什么问题。

摩尔对此表示赞同,他认为届时不一定需要每年强化当前疫苗。

“计划并加以考虑有合理性,不过当前还没有到那一步。”他说。

所有科学家包括研究新一代疫苗的科学家都认为,相较于应付比英国、南非和巴西还要麻烦的病毒变异,关键在于要尽快推动尽可能多的人接种疫苗,从而降低病毒传播。

他们说,如果有人宣称不用全民接种疫苗,年轻人感染后不太可能转为重症,就让病毒在年轻人群里传播,都会变成灾难的导火索。

“耐药病毒只在特定情况下出现,其中之一就是疫苗接种不足。”摩尔说。

他还担心延长两剂之间的时间,英国就是如此(两剂之间等待12周,以便给更多人注射第一剂)。因为辉瑞公司和Moderna的第一剂疫苗免疫应答到底能否持续超过四周,并没有数据支持。

他担心的是,如果病毒发现宿主有某种免疫反应,又无法完全消灭病毒并阻止其复制,就会对病原体施加选择压力,从而出现成功突变。

疫苗接种不足也是流感流行的原因之一。汉利指出,尽管每年流感导致超过5万美国人死亡,美国成人只有不到一半接种流感疫苗。

“大多数公共卫生项目在真正成功之前,都是其自身成功的牺牲品。”她说。“所以根除病原体才如此艰难。”(财富中文网)

译者:夏林

The South African. The Brazilian. The U.K.’s “Kent.”

They sound like they could be the names of some new hairstyle. But, as most virus trackers know, they are common shorthand for the new strains of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus behind the global pandemic. More transmissible, and in the case of the U.K. strain apparently more deadly, the new variants have forced governments around the world to impose tougher travel restrictions and, in some cases, new lockdowns.

The new variants also pose a problem for the first crop of vaccines. That’s because almost all the vaccines approved so far target the coronavirus’s spike protein. Mutations in this protein can reduce the vaccines’ effectiveness, potentially even negating any immunity.

So far, the solution vaccine makers and governments have proposed is to begin preparing updated versions of the existing vaccines that will prompt the immune system to make antibodies to the modified spike protein found in the new variants.

But if the virus keeps mutating, the world may find it is stuck in a perpetual game of cat and mouse, always trying to catch up with the latest strains of the virus, with a large portion of the world requiring an annual booster vaccination. This is essentially what happens with the flu virus now. And, as with the flu virus, there is a constant risk that researchers will misjudge and fail to spot an emerging and fast-spreading variant that will once again put many people at risk of hospitalization or death.

Might there be another way?

Some scientists think there is: either using more traditional vaccine technology that exposes people to the real virus and all of its proteins, or using new messenger RNA technology to create a universal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that would be effective against all current and future strains.

Why the variants are so worrisome

First, a little more background on the current situation: While the U.K. “Kent” strain, which is formally designated B.1.1.7, incorporates changes that make it easier to spread and may make it more deadly, the spike protein is not significantly changed, and the approved vaccines work well against it.

But mutations associated with the South African and Brazilian variants of the virus, formally called B.1.351 and B.1.1.248, respectively, render existing vaccines less effective. An analysis of data from the South African clinical trial of the University of Oxford and pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca vaccine showed that it could not prevent mild to moderate illness in those infected with the B.1.351 strain, although the company says it believes the vaccine probably still protects against severe COVID-19. Lab tests using blood samples from those vaccinated with Pfizer’s and Moderna’s messenger RNA-based vaccines also showed that higher antibody levels were needed to defeat the mutant strain than the original virus. But Moderna says it is confident its vaccine produces enough antibodies that it will still protect against moderate or severe disease.

Worryingly, scientists in the U.K. have now discovered a version of the B.1.1.7 “Kent” virus that also incorporates the same spike protein mutation, known as E484K, that the South African and Brazilian strains exhibit. This could have happened if a single person was infected with multiple strains of the virus, which then had a chance to mix their genetic material; or it could be that same mutation occurred spontaneously more than once.

Most of the COVID vaccines that have been approved for use so far were created with relatively new techniques: messenger RNA (mRNA) or modified adenovirus vectors. In both cases, the idea is to instruct human cells to produce one of the coronavirus’s proteins so that it prompts an immune response. The body then produces antibodies that can attach themselves to that protein and disable it. It is also hoped that other parts of the immune system—such as T-cells, which can kill infected cells—learn to recognize the protein as a sign of a foreign invader and kill those cells.

These technologies have some big advantages over traditional vaccine-making methods: They have excellent safety profiles, so the researchers working on the vaccines were reasonably sure they would not cause severe side effects—something which has been borne out in subsequent human clinical trials. The other good thing about them is that they can be tailored to a new virus very quickly, provided that virus has had its genome sequenced and there is an obvious protein to target, as was the case with SARS-CoV-2. The entire reason we have multiple vaccines in millions of people today, less than a year after the World Health Organization declared a pandemic, is largely because of these newer methods for creating vaccines.

The single-protein problem

But one downside of the way these techniques have been used to combat SARS-CoV-2 so far is that they instruct the cells to make a single virus protein. As a result, they are always going to be vulnerable to mutations in that particular protein. SARS-CoV-2 has four main structural protein groups: The S protein, or spike protein, is the best known. But it also has a nucleocapsid or N protein, a membrane or M protein, and an envelope or E protein. It might be possible to create vaccines that prompt an immune response to some or even all of these.

Two traditional vaccine-making techniques expose the body to all of these proteins because they use the actual virus itself. In one method, a living virus is “attenuated,” or weakened, by growing it in a way that makes it hard for the virus to rapidly reproduce. In another, the virus is “inactivated,” or killed using a chemical treatment, and then either administered whole, or sometimes broken into pieces. This is potentially safer than giving someone a living virus vaccine, which have a nasty habit of evolving back into dangerous pathogens.

No one is considering making a live SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, but several companies are working on inactivated ones. The Chinese company Sinovac’s vaccine uses the inactivated virus, and it has already been given to hundreds of thousands of people in China and in places like Brazil. The company says it is effective against the South African variant, but it has not published the data to support that claim. Meanwhile, clinical trials of the Sinovac vaccine in Brazil have shown it is 100% effective at preventing severe disease but may be only slightly more than 50% effective at preventing very mild illness.

Multivalent vaccines

French company Valneva, meanwhile, is working on an inactivated vaccine using the whole virus that might have advantages over those already approved, Thomas Lingelbach, the company’s chief executive officer, says. Because it uses the complete virus, the Valneva vaccine enables the immune system to potentially form a response to all possible epitopes—a term for the portions of the virus’s proteins that the immune system can recognize. Valneva also combines the inactivated virus with an adjuvant, a chemical substance that boosts the body’s immune response. What’s more, Valneva has experience producing multivalent vaccines—those that incorporate multiple virus strains in a single shot—and it could potentially produce one for SARS-CoV-2 too.

Lingelbach calls his company’s efforts the “third wave” of COVID-19 vaccine candidates. He believes they could have a multivalent version of Valneva’s vaccine authorized and available by next spring. (The first wave are those vaccines already approved, and the second wave are those currently in human clinical trials.) The U.K. government has already preordered 100 million doses of Valneva’s vaccine, some of which will be produced at the company’s manufacturing facility in Scotland.

The “universal” vaccine

Another approach may hold out the promise of a universal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The idea is to find epitopes that are both capable of eliciting a strong immune response and which are essential for the coronavirus’s reproduction. The idea is that if these proteins are essential for the virus’s life cycle, the virus won’t be able to escape the vaccine through successful mutations.

One company working on this approach is Belgian startup MyNeo. It uses machine learning to try to predict which virus epitopes will trigger the strongest immune response. It then looks for the subset of those epitopes that are found across all coronaviruses, says Cedric Bogaert, the company’s chief executive. He notes there are certain epitopes that are the same across not just all the SARS-CoV-2 variants, but also across the coronaviruses that cause SARS and MERS, as well as those known to infect minks and bats, two species that harbor coronaviruses and from which scientists think future strains may make the leap to humans. These common protein segments are what biologists call “well conserved,” and the speculation is that they don’t change much over time because their function is somehow essential to the virus’s viability.

Of particular interest is the SARS-CoV-2’s N protein, which is found inside the virus, wrapped around its RNA, the virus’s genetic code. It is thought the N protein plays a key role in helping the virus replicate after it has infected a cell. Portions of the N protein are very similar across all coronaviruses. And there are antibodies found within human cells that can recognize the N protein. Unlike the antibodies that latch on to the spike protein, these antibodies don’t prevent the cell from being infected. But when they find the N protein inside the cell, they break it into pieces, which the cell then displays on its surface. The body’s T-cells use these markers to identify the cell as infected and destroy it.

MyNeo is working with another Belgian company, eTheRNA, which has the ability to manufacture mRNA vaccines and also has created a proprietary adjuvant, which it calls TriMix that can significantly boost the body’s T-cell and B-cell response to a vaccine, Mike Mulqueen, eTheRNA’s head of business development, says. With help from MyNeo in selecting the right set of proteins, such as the N protein, to use with the TriMix in a vaccine, Mulqueen thinks they have a shot at producing a vaccine that will be much more effective against all future virus strains. The companies could have a vaccine in late-stage clinical trials within a year, he says.

Other scientists are skeptical

But there are skeptics of these approaches. Kathryn Hanley, a professor of biology at New Mexico State University who has worked on a dengue virus vaccine, says that there’s no reason to think that an inactive virus vaccine would create an immune response that is markedly different from what people experience with a natural COVID-19 infection. And in people with COVID-19, the spike protein seems to be principally responsible for the immune reaction.

This might be less of a problem for an mRNA-based approach, Mulqueen says. That’s because while it is true that in natural infections, the immune response to one particular epitope tends to dominate, if the body is presented with a different epitope in isolation—as could be the case with an mRNA vaccine—it is possible to elicit a strong immune response to that particular protein, particularly if an adjuvant is used.

John Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Cornell University’s Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, isn’t so sure. He says that while the way the body forms an immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is still not very well understood, there are “so many bread crumbs that say neutralizing antibodies are what matters.” The T-cell and B-cell responses, which may be triggered by other proteins, could play a role, he says, but it is antibodies that are critical, and they form in response to the spike protein. “The S protein is the only target for neutralizing antibodies, so there is not a lot of choice,” he says.

Even if Moore is wrong, Mulqueen acknowledges one potential longer-term problem with MyNeo’s and eTheRNA’s approach to a universal COVID-19 vaccine: While in theory the well-conserved epitopes are more likely to be essential to the virus’s life cycle and thus less likely to mutate successfully, that might not be true. Those proteins have never been subjected to significant selective pressure. Once a vaccine is introduced that targets these other proteins, it is possible, Mulqueen says, that the virus will evolve a way to evade it too.

An age-old challenge

The history of medicine is littered with failed attempts to create universal vaccines. “People have been breaking their hearts trying to develop a universal influenza vaccine for a long time,” Hanley says. She says they have even tried the same idea—finding conserved epitopes across strains—and it has so far failed. Influenza viruses mutate far faster than coronaviruses, which have a step in their replication process that essentially proofreads the copied genetic code for errors, slowing the introduction of mutations. “Coronavirus is not influenza, so it may be possible, but it’s not a sure thing,” she says.

Some scientists also believe that any talk of the need for a new crop of vaccines to address the new variants of SARS-CoV-2 is premature. “So far a critical line hasn’t been crossed,” says Paul Offit, a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and director of the Vaccine Education Center. Offit says crossing that line would mean people who were naturally infected with the original virus, or who had been immunized with the approved vaccines, were becoming reinfected with the new strains and becoming so ill from them that they needed hospitalization. He says he is encouraged by the high levels of antibodies seen in those who have received two doses of the current vaccines, particularly the mRNA ones from Pfizer and Moderna, and thinks those antibodies may be robust enough to continue to protect against severe disease even in the face of new strains.

He said he was hopeful, given that coronaviruses tend to mutate less than influenza, that if enough of the population can be vaccinated in the next several months—and given the fairly high number of people who have already had COVID-19—that transmission of the virus will start to drop off. With lower transmission, there is less chance for mutations that would be significant enough to warrant another generation of vaccines.

Moore shares this view, saying we’re not even sure that annual boosters to the current crop of vaccines will be necessary. “It is reasonable to plan and think about those things, but we’re not there yet," he says.

All the scientists, including those working on the next-wave vaccines, agreed that the key to preventing mutant strains even more troubling than the current U.K., South African, and Brazilian variants is to drive transmission of the virus down as low as possible by vaccinating as many people with the existing vaccines as quickly as possible. They say any discussion of not vaccinating countries’ whole populations and letting the virus run rampant through younger demographic groups, who are unlikely to become seriously ill from COVID-19, is a recipe for disaster.

“Resistant viruses arise under certain circumstances, and one of them is undervaccination,” Moore says. He also worries about extending the time between doses, as the U.K. has done (it is waiting 12 weeks between doses in order to give first doses to as many people as possible). That’s because there is no data from the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines on how long the immune response from the first dose lasts beyond the first four weeks. His concern is that if a virus finds a host with some immune response, but not enough to totally wipe it out and prevent replication, it puts selective pressure on the pathogen to find successful mutations.

Undervaccination is part of the reason why influenza has become endemic; even though flu kills more than 50,000 Americans each year, less than half of adults in the U.S. get the flu jab, Hanley notes. “Most public health programs become victims of their own success before they are truly successful,” she says. “That is why we have such trouble eradicating pathogens.”