拜登上任已过百天,曾叱咤新闻头条的特朗普一度淡出了人们的视线。而在当地时间4月29日,特朗普接受福克斯新闻专访时,除了如同习惯般地批评拜登,还称自己“100%”考虑再次参选总统。

回想去年年底,特朗普面对连任失败指控“选票造假”,引起轩然大波一事,似乎已成为过去时。但事实是,这件事情的余波尚未消散,且短时间内也无消散的可能,事情的后续发展可能会对美国社会带来更深远的影响。

有关操纵选举的指控,促使特朗普的支持者冲进国会大楼引发暴乱,同时也将参与这次大选的投票机公司Dominion推上风口浪尖。这家公司被特朗普支持者贴上了“怀疑”和“丑闻”的标签,工作人员也受到了死亡恐吓。

面对动摇公司根基的选票造假指控,Dominion决定反击,向谎言散布者提起诽谤诉讼。私营公司希望借此机会让其他政党为滥用政治话语权付出代价,其中还包括一家对21世纪公众生活产生巨大影响的媒体巨头,案件会产生什么样的影响,造成什么样的后果无法预测。

在案件最终结果出来前,来自多方的不信任和阴谋论可能会继续蔓延。而现实是,任何最终裁决可能需要三到四年才能做出,这意味着在此事解决前,美国还会进行一次总统选举……

12月9日,Dominion投票系统公司的高管妮可•诺莱特看完医生开车回家时,发现有一通未接客户来电。

该客户是一名选举官员,其所在辖区使用Dominion投票机。除打电话外,这位客户还给她发了一个网站链接。诺莱特在手机上打开了该网站,网站上出现了她的照片,照片上有鲜红的十字准星,就像被狙击步枪瞄准一样。

这个网站被人们称为“人民公敌”,它在诺莱特照片下面附上了内华达州一栋房屋的鸟瞰图。诺莱特很惊恐,因为她并不住在内华达州,而是住在Dominion所在的科罗拉多州。该网站公布的是她已退休父母的家。

几个月后,这位海军退伍老兵仍清晰记得,她母亲在看了那个网站后给她打电话时流露出的恐惧:“他们有我们家的照片,”她的母亲喘息着说。

这个网站公布了Dominion其他雇员和特朗普政府官员共十几个人的照片,诺莱特是其中之一。该网站指责他们参与了一场精心策划的阴谋,使用Dominion投票机(共有28个州使用)将选票从唐纳德•特朗普名下“转移到”乔•拜登名下,以此操纵去年11月份举行的总统选举。

当日晚些时候,联邦调查局前往诺莱特父母家提醒他们提高警惕。很快,诺莱特本人就收到了死亡威胁,有一封信寄到了她的个人邮箱,上面警告说:“你已时日无多。”

她一直不清楚是谁给她寄的信,但联邦调查局后来告知Dominion和其他人说,情报显示该暗杀名单与伊朗有关。

自从特朗普搬离白宫,几个月来,死亡威胁逐渐减少。但诺莱特是一个人生活,她仍能在周边发现可疑车辆。虽然她习惯在每天日出前和日落后散步,但现在只能在白天出门。

她说:“这是我退伍后第一次遭到安全威胁,我必须再次参加军训。”

和许多人一样,诺莱特的生活已被各种阴谋论背后那个最大的谎言所颠覆:该说法既牵强又恶毒,其目的是为推翻总统选举结果做最后一搏。

该说法源于一系列谣言,很多有类似经历的人都知道这是弥天大谎。法官、选举官员、网络安全专家和州长们都曾因质疑该说法而被公开骚扰,或因未能证实其不实而遭受言论抨击。其他人则遭受与诺莱特一样的命运,甚至受到更严重的骚扰。

Dominion公司产品战略和安全总监埃里克•库默在选举后约一周被某阴谋论拥护者在网上曝光。库默喜欢登山和烘焙面包,并且拥有核物理博士学位,但自从收到死亡威胁,他一直不敢回家,只能躲藏在美国境外;甚至他的律师都不知道他在哪里。

Dominion的回应得到了互联网和保守派的支持。

特朗普本人11月12日在推特上发文称,Dominion计票系统“删掉”其270万张得票。

但截至11月19日,其命运已无法逆转。当天,特朗普竞选团队成员纽约前市长鲁迪•朱利安尼和上诉律师及前联邦检察官西德尼•鲍威尔在位于华盛顿的共和党全国委员会总部举行了新闻发布会,发布会的重点是表明要对选举结果提出“法律挑战”。

此前,Dominion或许可以通过旨在纠正该记录的事实核查活动进行防御;公司已经聘请了危机公关专家以及一家顶级物理和网络安全公司。

“这些人毁了我们的公司,这是我从未料到的,”Dominion联合创始人兼CEO约翰•普洛斯说。但当他看到新闻发布会时,他感觉世界都崩塌了。

新闻发布会召开约25分钟后,朱利安尼第一次提到Dominion,这一刻令人难忘,他满头大汗。后来,他点名指出库默,称他是一个“邪恶的人”,是一个“亲极左翼政治运动”者。

朱利安尼和鲍威尔接着指称,Dominion的软件是依照独裁者雨果•查韦斯的指令在委内瑞拉开发的,其目的就是为了操纵选举,而且德国和西班牙也用该软件计票——该指控很容易被推翻,但对那些坚信共和党是受害者的支持者来说却很有煽动性。

“就像一场梦一样,”普洛斯说,他当时正和妻子、三个孩子及两只狗在多伦多的家里。“我以为他们要发动内战。”

当月早些时候,鲍威尔曾承诺要释放“克拉肯”(挪威民间传说中的海怪),即证明存在大规模投票舞弊行为的证据。司法部及共和党选举律师等权威人士均表示,这些证据尚未提交。相反,鲍威尔和朱利安尼接二连三地散布谣言,让民主党人逐步产生了怀疑。

在新闻发布会结束后的几天里,朱利安尼和鲍威尔在右倾有线电视网络上反复重申其对Dominion的指控,其中就包括收视率极高的福克斯新闻,该新闻台去年晚间黄金时段的收视率超过350万。

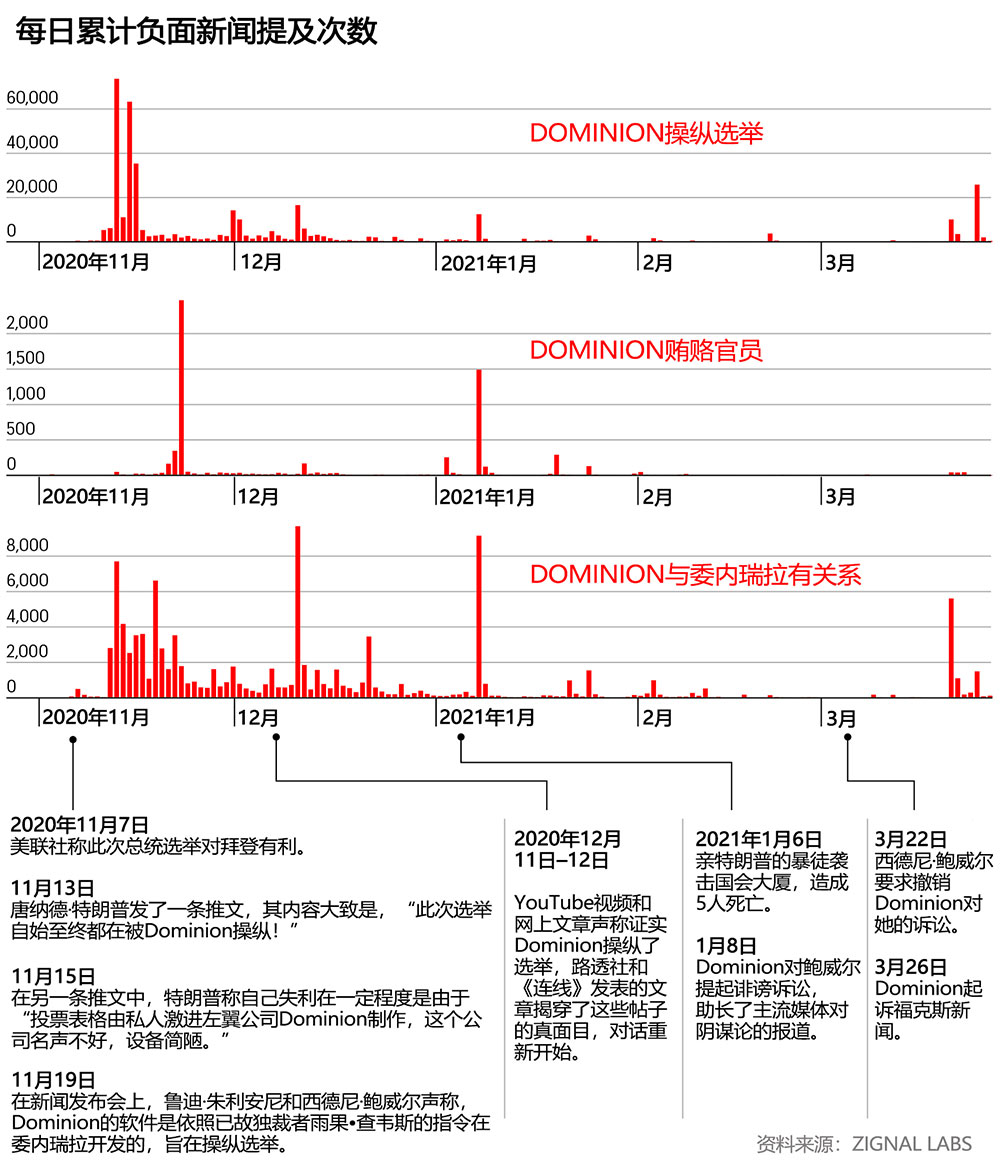

其他不太知名的媒体或官方媒体也进行了追踪报道:据追踪媒体舆情的Zignal Labs称,推特、YouTube和其他社交媒体提到Dominion操纵选举的次数已超过40万次。对于不计其数的特朗普支持者来说,Dominion很快成了怀疑和丑闻的代名词。

在选举前后的重重诽谤迷雾中,Dominion的回应加重了人们的疑虑。

据追踪右倾谣言的非营利组织Media Matters称,在美联社宣布拜登竞选成功两周后,福克斯新闻至少有774次对选举结果提出质疑或提出相关的阴谋论。

与此同时,东北大学等大学的研究人员发起的一项民调显示,半数以上共和党选民认为特朗普赢得了总统大选或不确定谁赢得了大选。

普洛斯在亚利桑那州的叔叔认为,Dominion在该阴谋中起了一定作用。“他不知道该相信什么了,”普洛斯说。

最终结果以悲剧形式上演。1月6日,一伙认为选举结果被偷走的暴徒闯入美国国会大厦,造成5人死亡。

两天后,Dominion提起了第一起诽谤诉讼。普洛斯在11月新闻发布会召开后不久就决定起诉。

“我们能够采取的唯一补救办法就是把他们告上法庭,”他说。“绝对要把真相公之于众。”

意外的原告

在此次美国破坏性选举乱局中,人们很容易忽略抨击Dominion造成的影响。

特朗普支持者在广泛散布关于大规模投票和选民舞弊的谣言(倘若基本上毫无根据)时,无疑会以政治言论自由为幌子为其指控进行辩护。但当鲍威尔和朱利安尼将矛头指向Dominion时,他们越过了底线。

现在,有关人员对某一党派提出了具体指控,这对美国经济极其不利。而且,由于这些指控很快就遭到了质疑,甚至是在共和党选举人员(他们有充分的动机希望这些指控是真的)进行的调查中,因此发言人反复重申这些指控,从法律上看,似乎是在显示“真实恶意”,或是不计后果地无视事实真相。

“如果他们满足所有这些条件,那么你就可以让人们承担责任,不管这是否涉及政治,”律师汤姆•克莱尔说。

克莱尔自七年前成立专接诽谤诉讼案件的律师事务所克莱尔•洛克以来,一直是诽谤诉讼案件的常胜将军;目前,他是Dominion的代理律师。

1月8日,Dominion对鲍威尔提起诽谤诉讼。接下来的几周,Dominion又对朱利安尼和MyPillow的CEO迈克•林德尔提起诽谤诉讼,起因是其发布了长达数小时处处表明Dominion是阴谋论主角的视频;每起诉讼索赔13亿美元。

Dominion于3月26日对福克斯新闻提起第四起诉讼,索赔16亿美元。(Dominion诉讼是福克斯因报道投票机而卷入的第二起诽谤大案:今年2月,规模明显不及Dominion的美国竞争对手Smartmatic也起诉福克斯,索赔27亿美元。)

法律专家说,这是一场围绕同一问题向多个被告提出大额索赔的历史性诉讼龙卷风。

“在我来看,此次诉讼独一无二,”Smartmatic代理律师埃里克•康诺利说,他曾代表一家牛肉公司就“粉红黏液”报道成功起诉ABC新闻,这是有记录以来一起最大的诽谤诉讼。“从声誉受损的角度来看,这是一场完美风暴。”

这些案件也可能会产生更重大的突破性影响,其后果是无法预测的:私营公司希望借此机会让其他政党为滥用政治话语权付出代价,其中包括一家对21世纪公众生活产生巨大影响的媒体巨头。

福克斯辩称,投票机指控本身就具有新闻价值,而且其播出时间受到《第一修正案》有关保障新闻自由规定的保护。

原告辩称,这些指控不实,而且一些福克斯新闻台主持人明显认同这些指控,已经使这些保护措施无效。

各公司计划以一种个体少有的方式来进行这场斗争。

政客们很少提起诽谤诉讼,尤其是在竞选活动最激烈的时候。不管对手散布的谣言具有多大的破坏性,他们都不能为了在法庭上弄清真相而分心。很少有个体,无论是公共的还是私人的,能承担得起这一代价。

另一方面,企业可能会因此浪费大量金钱,承受利润和收入损失带来的实际痛苦,从而表明谎言需要付出代价。

就投票机公司而言,康诺利指出,这些指控的矛头直指其品牌核心:准确性和可靠性。

“当你的核心商业模式遭受攻击时,诽谤诉讼可能是一条必经之路,”康诺利说。“这是恢复声誉的唯一方法。”一个极其重要的问题是,在保护其商业模式时,这些不太知名的公司能否在公开辩论中重塑其准确性和可靠性规则。

影射的余震

媒体研究公司ZIGNAL LABS的数据说明了各种未经证实的对DOMINION的指控是如何在网上持续传播的。

不受信任的行业

2003年,约翰•普洛斯在其位于多伦多的地下室创办了Dominion。约翰•普洛斯是加拿大人,在美国没有投票权,最近他卖掉了第一家初创公司(一家电信技术公司),从硅谷搬回了老家。

在2000年美国总统选举(该选举因蝴蝶选票和孔屑废票引发了争议)后,他有了一个大胆的创意。国会后来通过了《帮助美国投票法案》,主要是为了改善投票技术和保证投票无障碍性。普洛斯想建立一个系统,既能帮助盲人投票,同时又不违背选票保密性。

他以1920年加拿大《自治领选举法》(该法案赋予了女性选举权)为这家公司起名。“我们认为这是对帮助选民投票的人表达的一种崇高敬意,”普洛斯说。

视力不好的选民也可使用Dominion投票机,普洛斯逐步在各州和地方政府建立了广泛的客户群。他招募了一个专门负责完成公司民主使命的员工,若非如此,可能需要应对“大量的”工作时间和七天选举季工作周。

到2020年,Dominion成为美国第二大投票机公司,其投票机已在美国28个州和波多黎各进行的1,500次选举中使用,员工约300人。

但Dominion加入了一个已经饱受各政治派别质疑的行业。在推动投票技术现代化进程中,一些辖区已升级为电子系统,但其可追溯性并不透明,尤其是在投票机未留下任何纸质记录时。

2006年,政治接班人、环保专业律师及后来成为反疫苗活动家的小罗伯特•肯尼迪在《滚石》杂志上发表了一篇文章,质疑共和党是否在这些投票机帮助下“偷走了” 2004年选举结果。

2008年,普林斯顿大学计算机科学教授安德鲁•阿佩尔演示了如何用螺丝刀入侵投票机。

这种妄想促使人们重新采用更老套的方法。如今的大多数投票机,包括Dominion投票机,都会生成或统计可用于重新计票的纸质选票。

尽管如此,不信任危机仍在蔓延,尤其是在2016年总统选举期间,关于俄罗斯涉嫌干预选举的报道不断出现。(这种干预包括广泛散布谣言,但调查称并无任何证据表明投票系统被篡改。)

Dominion也未能免受怀疑:绿党总统候选人吉尔•斯坦因四年前在威斯康星州失利后,起诉要求审查威斯康星州使用的Dominion 投票机和其他投票机的源代码;该诉讼仍在进行中。

尽管存在这种不信任的背景,但若非因安特里姆县,2020年选举可能对Dominion并无任何影响。

密歇根州北部是共和党的大本营,但在大选之夜,截至当地时间周三上午,拜登及选票数低的民主党人似乎以压倒性优势获胜。竞选律师提请选举官员注意这一反常现象时,他们发现了问题:选票上的候选人发生了变化,但地方官员并未用新模板重新编程使用Dominion软件的一些投票机。结果,选民的投票在最初计票时基本上被调低了一行,其选票计入了另一政党的候选人名下。

在错误被发现当日,选举官员就纠正了这一人为错误;最终,特朗普赢得了安特里姆县。安特里姆县事件“表明问题和解决过程促成了正确的结果,”专门研究选举技术的无党派非营利组织OSET研究所的全球技术开发总监爱德华•佩雷斯说。

“但仍借此来指控选举被操纵,这令人难以置信。”

但损失已经造成,阴谋论者仍心存疑虑。Dominion投票机已在一些竞争最激烈的州使用:密歇根州、佐治亚州和亚利桑那州等。

11月6日,在选举正式开始前,亚利桑那州共和党众议员保罗•戈萨尔以安特里姆县事件为例,开始在推特上呼吁“审查所有Dominion软件”的“巨大欺诈可能性”。调查呼声越来越高,而决心为选举结果而战的特朗普总统也乐于扩大其影响。

在鲍威尔和朱利安尼召开新闻发布会时,事情变得更加奇怪。

阴谋论贩子认为Dominion有一个邪恶的伙伴:委内瑞拉独裁者查韦斯,他于2013年去世。鲍威尔的这一说法在很大程度上是基于一份经过大幅修改的宣誓书,该宣誓书来自一位所谓的“委内瑞拉告密者”,他声称Smartmatic自己开发的软件能够偷偷篡改对查韦斯的投票,而Dominion的系统就是从该模型衍生出来的。

Smartmatic和Dominion都极力否认这种说法。但这种说法确实与现实有着扭曲的联系,因而会让那些愿意相信它的人听起来感觉更可信。Smartmatic的创始人是委内瑞拉人;美国外国投资委员会早在2006年就调查了该公司与委内瑞拉的关系;Dominion收购了Smartmatic几年前剥离的一家子公司。

这根纤细的稻草成了鲍威尔和朱利安尼打击Dominion的棍子。据Zignal称,社交媒体已超过11万次提及Dominion与委内瑞拉的关系。(至于Smartmatic,在美国2020年选举中,只有洛杉矶使用了其投票机。)

选举前后发生的一系列怪事件进一步催生了怀疑论。由于人们担心感染新冠肺炎,数以百万计的人缺席投票,这一情况前所未有,因此,投票结果很接近,再加上计票过程很长,致使全国选民都非常关注此次选举,政党律师和民调观察者都在努力让其支持的人取胜。

“就像觉得存放时间长的鱼有臭味一样,人们总会对原先的选举结果有所质疑,这已是老生常谈的事,”马克•布拉登说,他曾任RNC首席顾问,现就职于BakerHostetler(他称对Dominion的指控是“纯属虚构,完全是胡说”)。

再者,某总统花数月时间做铺垫,一旦竞选失败,就大声疾呼欺诈,阴谋论的时机已经成熟。

“这些指控的依据极易让人轻信,”一位共和党律师说。“Dominion很倒霉。”

尽管如此,鉴于安特里姆县的失误,Dominion投票机转移选票的理论最初似乎站得住脚,但当共和党官员前往拜登获胜的各州寻找证据时,谎言一下子就露馅了。

选举律师查理•斯皮斯代表有望取胜的共和党候选人约翰•詹姆斯参加了2020年密歇根州参议院席位竞选。如果安特里姆县的问题已涉及该州使用Dominion投票机的其他县,他的候选人就会获胜。

“我的目标是找到能够证明存在该问题并足以影响结果的证据,”斯皮斯说。他表示,他试图驳回鲍威尔提出的每一项指控,希望能有所帮助,但都落空了。

“对于这一惊天阴谋,我感到难以理解的是,这些投票机之间并没有互联,”他说。“一台投票机并不能改变全州的选举结果。”

全国各地的共和党竞选律师和候选人也在做着同样的事情。在亚利桑那州,州内外的律师们都在调查Dominion投票机,但经过近一周的苦苦寻找以及与技术人员和选举工作人员面谈,他们并没有发现任何统计异常、不当互联网连接,也没有发现任何其他问题。

在弗吉尼亚州,共和党官员和律师在11月19日召开的新闻发布会上听到朱利安尼说他们州存在选举欺诈,感到很惊讶,他们并没有从自己的民调观察者那里听到类似的消息。当他们要求特朗普竞选团队给出解释时,没有人作出回应。

如果存在不当行为,官员们认为不要求调查真是太奇怪了。“我们问他们掌握了哪些证据,但从未得到任何人的答复,”共和党竞选律师、竞选财务合规公司Election CFO创始人克里斯•马斯顿表示。“但让我们感到欣慰的是,弗吉尼亚州并没有普遍存在基于投票机的欺诈行为。”

鲍威尔自始至终都在通过媒体,同时也在幕后为自己辩护。竞选落败的共和党候选人称,他们接到鲍威尔和她的团队来电,敦促他们“继续战斗”,她“要打开一个缺口”,他们“最好参与进来”。

但当竞选律师要求提供证据时,“我们并未收到任何证据,只是了解了大概情况,‘太糟糕了,他们作弊,选举结果被偷走了,’”一位共和党律师说。“根本没有这回事,”另一律师说。

“气隙”

共和党人发现的或未发现的情况都恰恰是投票系统专家们所期望的。在科技含量较低的新时代,包括Dominion投票机在内的大多数投票机均设计成完全离线运行,并未连接互联网,用网络安全术语来说,它们是“气隙”的。

普林斯顿大学计算机科学家阿佩尔用螺丝刀入侵了一台投票机。他指出,目前至少有几种方法可以远程破坏这一新产物,通常涉及一个互联网接触点。一种是在投票机运出仓库之前安装恶意软件,如通过对Dominion员工进行网络钓鱼攻击。

另一种方法是破解县政府官员用来为地方一级投票机编程的笔记本电脑,这通常要将选票数据上传到存储卡或U盘,并通过添加欺诈算法来向投票机传输数据。如果成功的话,这些投票机可能会被“以联网方式入侵,一次入侵可以涉及数千台投票机,”阿佩尔说。

不过,未来的黑客们仍面临着巨大的障碍。

其一,按照目前的做法,即使是编程用笔记本电脑,除极少数失误外,也无法连接到互联网,这使得远程黑客几乎无法访问。

其二,即使攻击者确实在投票机上安装了欺诈性的投票切换软件,在选举前投票机进行各种认证和准确性测试中,或者在某些州进行选举后审查中,它也会被发现。

“在很多地方,搞破坏的人必须一次又一次地逃避检测,”OSET的佩雷斯解释说。最后,如果纸质选票与投票机计票结果相符, 2020年重新计票的各州就属于此种情况,“就是投票电脑未被黑客入侵的有力证据,”阿佩尔说。

换句话说,倘若发生鲍威尔和朱利安尼所述的黑客攻击,该攻击在2020年就已经被发现了。从11月到次年1月,手工重新计票已涵盖超过1,000台Dominion投票机,包括对佐治亚州500多万张选票进行的第三次重新计票。并没有发现任何重大的错误或违规行为。

选举后不久,有关更世俗指控的法律质疑就土崩瓦解了,其他律师事务所不再接手特朗普竞选事宜,竞选法律战略和法律投诉事宜就落到了朱利安尼和鲍威尔等盟友的手中。鲍威尔以擅长上诉诉讼而闻名,她有着丰富的法律经验和敏锐的洞察力。

但是,鲍威尔和她的团队提交的有关Dominion诉讼案情摘要的证据,就像是由一些无关新闻组成的大杂烩。一些文件将下载到运行Dominion软件的笔记本电脑上的一款电脑游戏作为潜在黑客攻击的证据;一些文件则将异常高的投票率作为可疑的证据。在一些证词中,证人解释说,他们的证词来自在谷歌搜索中找到的资讯。

12月,亚利桑那州的一名法官完全驳回了鲍威尔提起的一项诉讼,她认为:“以公众谣言和影射为依据的指控不能取代联邦法院严肃认真的辩护程序。”

评论者认为,鲍威尔及其盟友在法庭和媒体上公布对Dominion不利的证据,充其量只能证明存在确认偏差,即阴谋论者将一次违规行为作为阴谋的证据,但这并不能类推。

换句话说,仅仅因为一台投票机可能被黑客攻击并不表示它会产生明显影响,马克•布莱登最近发现自己已对此做了很多解释。

布拉登,RNC的前首席律师,在他的职业生涯中已经处理了约100起重新计票事件,他认为,这一数量比国内任何其他共和党律师都多。最近,党内其他人一直打电话向他询问Dominion指控事宜,他一直在极力回避。

“他们认为,‘哦,这么多烟,一定是哪里着火了。’”布拉登说。“而实际情况是,每个人心中都有疑虑。这不是烟,这些只是令人迷惑的云雾。”

截至2020年圣诞节,特朗普竞选团队及其同僚提起的50多起选举不当诉讼均被驳回,法律和网络安全机构也越来越不关心有关Dominion的故事。

在12月卸任前,司法部长威廉•巴尔表示,经过联邦调查,“到目前为止,我们尚未发现可能会影响选举结果的大规模欺诈行为。”

3月,美国司法部与国土安全部网络安全和基础设施安全局共同解密了一份联合报告,该报告涉及“一个或多个外国政府”控制投票机和操纵计票的“多项公开指控”。报告称,经过调查,这些机构“认定这些政府不可信。”

事实、观点和新闻

去年秋天,普洛斯收到了许多恐吓信和死亡威胁,此外,还收到了来自纽约长岛一位希腊东正教牧师的一条意外消息。牧师猜中了普洛斯所属的教派,并表示愿意提供支持。他们从未谋面,但已交谈数次,牧师给普洛斯寄了一些有关精神和历史领域的书籍。

“我们曾谈到这并不是历史上第一次发生的不公平事情,看来没希望了,”普洛斯回忆道。“他一再提醒我,事实上,我们站在历史正确的一边。”

在一次心理咨询会上,牧师用温斯顿•丘吉尔的话宣泄了一下情绪:“如果你正在经历地狱,继续前进。”对于普洛斯和他的员工来说,这句名言现在成了箴言。

Dominion的反击已经达到了一定的预期效果。11月和12月,Dominion和Smartmatic分别就福克斯新闻宣传的指控向其发出了警告信。此后,福克斯新闻针对这些指控进行了“事实核查”,还采访了OSET的佩雷斯,结果发现并没有这种事。

鲍威尔、朱利安尼以及这个故事本身从一月初开始就基本上在该新闻网消失了。

然而,该故事仍在保守派媒体和社交媒体上传播,普洛斯和他的同事说,损害仍未停止。

作为一家私人控股公司,Dominion并未披露其财务状况,但其对福克斯提起的最新诉讼列举了其声称遭受的一些损害,包括预期在俄亥俄州和路易斯安那州进行的投票机交易,这些交易自选举以来已被搁置。

该公司要求赔偿的损失包括6亿美元利润损失、至少10亿美元企业价值损失以及数十万美元安全和“打击谣言运动”费用。尽管索赔金额之高令人震惊,但Dominion的律师克莱尔对此进行了辩护。

“在我从业25年来,此类消息波及的范围以及听到这一消息、相信这一消息并付诸行动的人数都是前所未有的。”

Dominion和Smartmatic的律师知道,为了胜诉,这还不足以证明这个弥天大谎并非事实。因为从法律角度看,两家公司可能会被视为“公众人物”(公司几乎总是这样),所以要以更高的标准来证实这明显是诽谤:他们需要证明存在真实恶意,即虚假信息散布者故意撒谎或不顾后果地无视事实真相。

也就是说,在现实和“另类事实”不相容时代,审判可能会引发一个尤为紧迫的问题:相信虚假说法是否属于不计后果地无视事实?

被告在Dominion案件中的回应以不同的方式反映了这一问题。

迄今为止,鲁迪•朱利安尼一直在Dominion和Coomer提起的诉讼中进行自辩,但他没有回应置评请求,他提交的法庭文件也几乎未透露他的策略。

MyPillow的CEO迈克•林德尔尚未在法庭上对Dominion作出回应,但他表示,他计划将其索赔金额加倍。林德尔说,他收到了“确凿证据”,他计划在后续的证据公示中公开该证据,但他并未允许《财富》查看该证据。

“我们将用历史上最大一起《第一修正案》诉讼来反诉他们,”他说,并补充道,“如果你说的是某人的真相,就不是诽谤。”

西德尼•鲍威尔在3月底对Dominion的诉讼作出回应,提出了驳回诉讼的动议。

她在诉讼摘要中提出的其中一个论点极具挑衅性:即使她的声明可被证明真伪,诉讼摘要写道,“任何理智的人都不会认为,这些声明是真实的事实陈述。”

在某种程度上,这让诽谤专家感到困惑,因为这似乎削弱了鲍威尔的权威。《第一修正案》律师、耶鲁法学院信息社会项目的高级研究员桑德拉•巴伦认为,这一目标不太可能实现:“在我看来,这种辩护对惊人杂谈节目主持人来说是最好的猛料——‘没有人把我们说的话当真,’”巴伦说。

“但我认为这对律师来说是一个有力论点。”鲍威尔的律师霍华德•克林亨德勒在接受《财富》采访时澄清了这一观点。他认为,鲍威尔的公开声明并非事实,但在她出示其他人(她认为的专家证人)的证词时,可形成意见。

克林亨德勒承认,这些证人的证词可能站不住脚,但他说,不应凭此认为他们的论点无效,或指责鲍威尔。“这些专家报告并非一派胡言,他们有文件、截图和分析为据。”克林亨德勒说。

他和鲍威尔曾希望,且现在仍然希望他们的文件足以“证明”有必要在法庭上公开更多证据。

媒体法律资源中心执行主任乔治•弗里曼,曾长期担任《纽约时报》的诽谤诉讼辩护律师,他说,这种观点犯了“最基本的错误”。

“那些被披露的事实必须属实,”他说。如果不属实,“辩护就会土崩瓦解。”(鲍威尔在法庭上也可能会被责难,因为她把这些“意见”说成是事实。例如,12月初,在卢•多布斯同名的福克斯商业黄金时段节目中,她对主持人说:“如果你不了解事情的原委,你就会像傻瓜一样,愚蠢得要命,因为任何人都愿意看到真凭实据。”)

事实与观点的区别,以及谁对前者的准确性负责,必然是对福克斯新闻诉讼的主题,无疑是投票机诉讼中最重要的部分。

律师们说,无论结果如何,这些案件都会在新闻界掀起涟漪,重新定义各组织在报道和纠正谣言方面的作用。

截至本文发表,福克斯尚未对Dominion提起的诉讼作出回应,但对Smartmatic诉讼的回应让我们对其策略有了一定了解。(福克斯新闻拒绝让工作人员就此接受采访。)

福克斯新闻在Smartmatic案件中辩称,特朗普总统发起的选举质疑具有“无可否认的新闻价值”,而且是“公众关注的问题”——法律给予此类言论更大保护。

“如果《第一修正案》有效,福克斯就不为公平报道和评论在激烈竞争和积极诉讼的选举中发生的竞争性指控负责,”福克斯在一份声明中说。福克斯还指出了其播出的“事实调查部分”,此外,其电视台工作人员也表示,没有证据表明存在广泛欺诈行为。

弗里曼称,福克斯似乎以中立报道为策略进行辩护,即新闻媒体可报道和重申责任人提出的重要主张。许多人认为媒体应该拥有这一权利,弗里曼也是其中之一。

然而,很少有法院承认中立报道这一特权,而且在福克斯的总部所在地纽约(Smartmatic起诉地),法院不承认这一特权。

律师们说,即使法院承认,福克斯仍有可能在中立问题上摔跟头。毕竟,陪审团必须考虑其全部报道内容以及其是否赞同嘉宾的观点。

承认这一特权促使Dominion和Smartmatic提起诉讼。例如,11月,多布斯与鲍威尔讨论完Dominion有关事宜时,称他“很高兴”鲍威尔正在“努力解决这一切。这是一个肮脏的烂摊子,而且比我们任何人想象的都要险恶得多。”(福克斯在2月Smartmatic起诉后第二天取消了多布斯的节目,但该电视台称,取消节目与诽谤案无关。)

如果福克斯败诉,Dominion和一些主流评论员可能会为这场胜利欢呼,会称其为企业对抗谣言的胜利,是事实与替代事实之间的界限,也可能成为未来诉讼的标准。

耶鲁大学的巴伦说,小心事与愿违。遏制虚假新闻(如果你愿意那样的话)实际上可能会对新闻自由和言论自由总体上产生寒蝉效应。

“希望这只会让那些有可能在诽谤诉讼中败诉的人感到寒意。”她说。“我认为,不管好坏,在这场诉讼中,美国可能会有机会了解许多关于诽谤法的限制。”

除《第一修正案》之外,还可依据其他法律追究这一弥天大谎散布人的责任。鲍威尔和朱利安尼以及其他几位提出选举质疑的律师,正遭到政府官员起诉,意在彻底取消其律师资格。

一些散布鲍威尔和朱利安尼等言论并采取行动的立法者正被一些资助者惩罚:多家公司已不再为拒绝证明2020年选举有效性的立法者的竞选活动提供经费。

还有一个问题是,Dominion的诉讼推进是否足够快、足够深远,从而能够产生影响。

具有讽刺意味的是,Dominion的说法中作为例证的不利信息可能会使人们更加难以了解真相。一旦进入审判阶段,聘请足够多未受充斥各处的指控影响的陪审员可能是一大挑战。

任何最终裁决可能需要三到四年才能做出,也就是说,在裁决证实投票机公司无罪之前,可能还会举行一次总统选举。如果Dominion胜诉,这一结果是否会影响信仰阴谋论的数百万人,尚不得而知。

对普洛斯来说,有关诚信和民主的问题远比这些担忧重要。他说,Dominion目前自己支付律师费,有足够的财力应对持久诉讼,并不打算和解。

“在真相未揭晓前,我们不会提出和解。”他说。“我们对此并不感兴趣。”与此同时,普洛斯和他的同事们接受了另一项使命:向美国选民解释选举程序。只要大多数辖区都使用纸质选票,选举专家预计,甚至是少数持反对意见的人最终也会采用纸质选票,人们就比较容易心安。

Dominion高管尼科尔•诺莱特已将消除谣言作为首要任务。“你不必相信我们的话,”她一再地解释道。若无明显证据:“你可以手工重新统计纸质选票;你也可以用投票机重新统计选票,”她说。

今后,更多州可能会这样做,这可能是在阴谋论蔓延之前消除阴谋论的一种更有效的方式。(财富中文网)

译者:Min

拜登上任已过百天,曾叱咤新闻头条的特朗普一度淡出了人们的视线。而在当地时间4月29日,特朗普接受福克斯新闻专访时,除了如同习惯般地批评拜登,还称自己“100%”考虑再次参选总统。

回想去年年底,特朗普面对连任失败指控“选票造假”,引起轩然大波一事,似乎已成为过去时。但事实是,这件事情的余波尚未消散,且短时间内也无消散的可能,事情的后续发展可能会对美国社会带来更深远的影响。

有关操纵选举的指控,促使特朗普的支持者冲进国会大楼引发暴乱,同时也将参与这次大选的投票机公司Dominion推上风口浪尖。这家公司被特朗普支持者贴上了“怀疑”和“丑闻”的标签,工作人员也受到了死亡恐吓。

面对动摇公司根基的选票造假指控,Dominion决定反击,向谎言散布者提起诽谤诉讼。私营公司希望借此机会让其他政党为滥用政治话语权付出代价,其中还包括一家对21世纪公众生活产生巨大影响的媒体巨头,案件会产生什么样的影响,造成什么样的后果无法预测。

在案件最终结果出来前,来自多方的不信任和阴谋论可能会继续蔓延。而现实是,任何最终裁决可能需要三到四年才能做出,这意味着在此事解决前,美国还会进行一次总统选举……

12月9日,Dominion投票系统公司的高管妮可•诺莱特看完医生开车回家时,发现有一通未接客户来电。

该客户是一名选举官员,其所在辖区使用Dominion投票机。除打电话外,这位客户还给她发了一个网站链接。诺莱特在手机上打开了该网站,网站上出现了她的照片,照片上有鲜红的十字准星,就像被狙击步枪瞄准一样。

这个网站被人们称为“人民公敌”,它在诺莱特照片下面附上了内华达州一栋房屋的鸟瞰图。诺莱特很惊恐,因为她并不住在内华达州,而是住在Dominion所在的科罗拉多州。该网站公布的是她已退休父母的家。

几个月后,这位海军退伍老兵仍清晰记得,她母亲在看了那个网站后给她打电话时流露出的恐惧:“他们有我们家的照片,”她的母亲喘息着说。

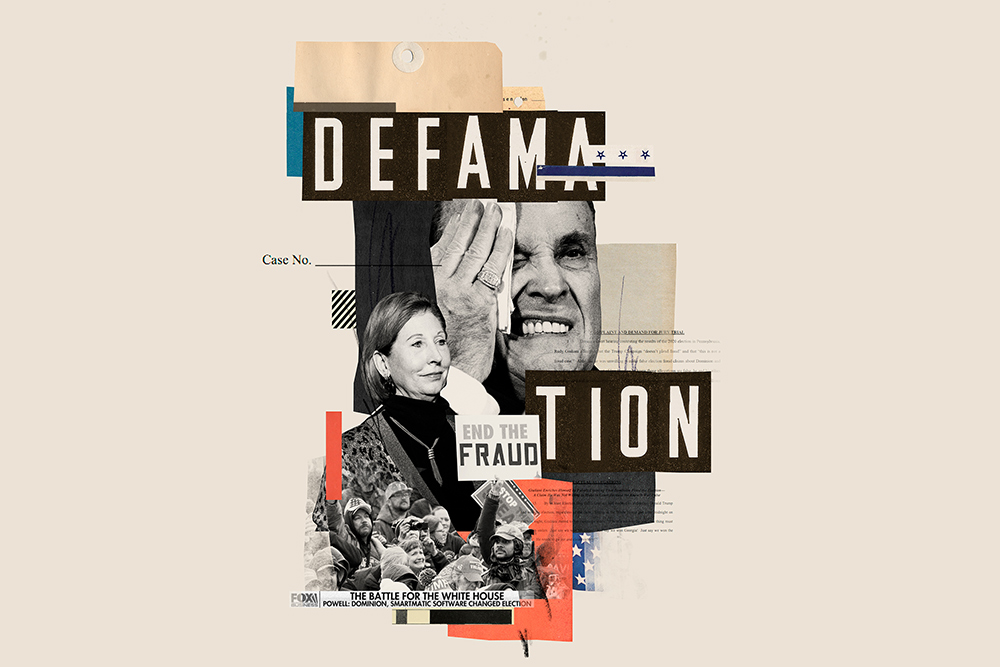

插图由纳扎里奥•格拉齐亚诺提供。原始照片:朱利安尼和鲍威尔:汤姆•威廉姆斯——CQ-ROLL公司/盖蒂图片社(2);民众:埃里克•李——彭博社/盖蒂图片社;诉讼:美国DOMINION公司、DOMINION投票系统公司和DOMINION投票系统集团诉鲁道夫W.朱利安尼案;福克斯新闻查询台:美国DOMINION公司、DOMINION投票系统公司以及DOMINION投票系统集团诉福克斯新闻网络有限责任公司案

这个网站公布了Dominion其他雇员和特朗普政府官员共十几个人的照片,诺莱特是其中之一。该网站指责他们参与了一场精心策划的阴谋,使用Dominion投票机(共有28个州使用)将选票从唐纳德•特朗普名下“转移到”乔•拜登名下,以此操纵去年11月份举行的总统选举。

当日晚些时候,联邦调查局前往诺莱特父母家提醒他们提高警惕。很快,诺莱特本人就收到了死亡威胁,有一封信寄到了她的个人邮箱,上面警告说:“你已时日无多。”

她一直不清楚是谁给她寄的信,但联邦调查局后来告知Dominion和其他人说,情报显示该暗杀名单与伊朗有关。

自从特朗普搬离白宫,几个月来,死亡威胁逐渐减少。但诺莱特是一个人生活,她仍能在周边发现可疑车辆。虽然她习惯在每天日出前和日落后散步,但现在只能在白天出门。

她说:“这是我退伍后第一次遭到安全威胁,我必须再次参加军训。”

和许多人一样,诺莱特的生活已被各种阴谋论背后那个最大的谎言所颠覆:该说法既牵强又恶毒,其目的是为推翻总统选举结果做最后一搏。

该说法源于一系列谣言,很多有类似经历的人都知道这是弥天大谎。法官、选举官员、网络安全专家和州长们都曾因质疑该说法而被公开骚扰,或因未能证实其不实而遭受言论抨击。其他人则遭受与诺莱特一样的命运,甚至受到更严重的骚扰。

Dominion公司产品战略和安全总监埃里克•库默在选举后约一周被某阴谋论拥护者在网上曝光。库默喜欢登山和烘焙面包,并且拥有核物理博士学位,但自从收到死亡威胁,他一直不敢回家,只能躲藏在美国境外;甚至他的律师都不知道他在哪里。

Dominion的回应得到了互联网和保守派的支持。

特朗普本人11月12日在推特上发文称,Dominion计票系统“删掉”其270万张得票。

但截至11月19日,其命运已无法逆转。当天,特朗普竞选团队成员纽约前市长鲁迪•朱利安尼和上诉律师及前联邦检察官西德尼•鲍威尔在位于华盛顿的共和党全国委员会总部举行了新闻发布会,发布会的重点是表明要对选举结果提出“法律挑战”。

此前,Dominion或许可以通过旨在纠正该记录的事实核查活动进行防御;公司已经聘请了危机公关专家以及一家顶级物理和网络安全公司。

“这些人毁了我们的公司,这是我从未料到的,”Dominion联合创始人兼CEO约翰•普洛斯说。但当他看到新闻发布会时,他感觉世界都崩塌了。

持久诉讼当事人。约翰•普洛斯,照片于2021年3月摄于亚特兰大。由查克·马库斯拍摄

新闻发布会召开约25分钟后,朱利安尼第一次提到Dominion,这一刻令人难忘,他满头大汗。后来,他点名指出库默,称他是一个“邪恶的人”,是一个“亲极左翼政治运动”者。

朱利安尼和鲍威尔接着指称,Dominion的软件是依照独裁者雨果•查韦斯的指令在委内瑞拉开发的,其目的就是为了操纵选举,而且德国和西班牙也用该软件计票——该指控很容易被推翻,但对那些坚信共和党是受害者的支持者来说却很有煽动性。

“就像一场梦一样,”普洛斯说,他当时正和妻子、三个孩子及两只狗在多伦多的家里。“我以为他们要发动内战。”

当月早些时候,鲍威尔曾承诺要释放“克拉肯”(挪威民间传说中的海怪),即证明存在大规模投票舞弊行为的证据。司法部及共和党选举律师等权威人士均表示,这些证据尚未提交。相反,鲍威尔和朱利安尼接二连三地散布谣言,让民主党人逐步产生了怀疑。

在新闻发布会结束后的几天里,朱利安尼和鲍威尔在右倾有线电视网络上反复重申其对Dominion的指控,其中就包括收视率极高的福克斯新闻,该新闻台去年晚间黄金时段的收视率超过350万。

其他不太知名的媒体或官方媒体也进行了追踪报道:据追踪媒体舆情的Zignal Labs称,推特、YouTube和其他社交媒体提到Dominion操纵选举的次数已超过40万次。对于不计其数的特朗普支持者来说,Dominion很快成了怀疑和丑闻的代名词。

在选举前后的重重诽谤迷雾中,Dominion的回应加重了人们的疑虑。

据追踪右倾谣言的非营利组织Media Matters称,在美联社宣布拜登竞选成功两周后,福克斯新闻至少有774次对选举结果提出质疑或提出相关的阴谋论。

与此同时,东北大学等大学的研究人员发起的一项民调显示,半数以上共和党选民认为特朗普赢得了总统大选或不确定谁赢得了大选。

普洛斯在亚利桑那州的叔叔认为,Dominion在该阴谋中起了一定作用。“他不知道该相信什么了,”普洛斯说。

最终结果以悲剧形式上演。1月6日,一伙认为选举结果被偷走的暴徒闯入美国国会大厦,造成5人死亡。

两天后,Dominion提起了第一起诽谤诉讼。普洛斯在11月新闻发布会召开后不久就决定起诉。

“我们能够采取的唯一补救办法就是把他们告上法庭,”他说。“绝对要把真相公之于众。”

意外的原告

在此次美国破坏性选举乱局中,人们很容易忽略抨击Dominion造成的影响。

特朗普支持者在广泛散布关于大规模投票和选民舞弊的谣言(倘若基本上毫无根据)时,无疑会以政治言论自由为幌子为其指控进行辩护。但当鲍威尔和朱利安尼将矛头指向Dominion时,他们越过了底线。

现在,有关人员对某一党派提出了具体指控,这对美国经济极其不利。而且,由于这些指控很快就遭到了质疑,甚至是在共和党选举人员(他们有充分的动机希望这些指控是真的)进行的调查中,因此发言人反复重申这些指控,从法律上看,似乎是在显示“真实恶意”,或是不计后果地无视事实真相。

“如果他们满足所有这些条件,那么你就可以让人们承担责任,不管这是否涉及政治,”律师汤姆•克莱尔说。

克莱尔自七年前成立专接诽谤诉讼案件的律师事务所克莱尔•洛克以来,一直是诽谤诉讼案件的常胜将军;目前,他是Dominion的代理律师。

1月8日,Dominion对鲍威尔提起诽谤诉讼。接下来的几周,Dominion又对朱利安尼和MyPillow的CEO迈克•林德尔提起诽谤诉讼,起因是其发布了长达数小时处处表明Dominion是阴谋论主角的视频;每起诉讼索赔13亿美元。

Dominion于3月26日对福克斯新闻提起第四起诉讼,索赔16亿美元。(Dominion诉讼是福克斯因报道投票机而卷入的第二起诽谤大案:今年2月,规模明显不及Dominion的美国竞争对手Smartmatic也起诉福克斯,索赔27亿美元。)

法律专家说,这是一场围绕同一问题向多个被告提出大额索赔的历史性诉讼龙卷风。

“在我来看,此次诉讼独一无二,”Smartmatic代理律师埃里克•康诺利说,他曾代表一家牛肉公司就“粉红黏液”报道成功起诉ABC新闻,这是有记录以来一起最大的诽谤诉讼。“从声誉受损的角度来看,这是一场完美风暴。”

这些案件也可能会产生更重大的突破性影响,其后果是无法预测的:私营公司希望借此机会让其他政党为滥用政治话语权付出代价,其中包括一家对21世纪公众生活产生巨大影响的媒体巨头。

福克斯辩称,投票机指控本身就具有新闻价值,而且其播出时间受到《第一修正案》有关保障新闻自由规定的保护。

原告辩称,这些指控不实,而且一些福克斯新闻台主持人明显认同这些指控,已经使这些保护措施无效。

各公司计划以一种个体少有的方式来进行这场斗争。

政客们很少提起诽谤诉讼,尤其是在竞选活动最激烈的时候。不管对手散布的谣言具有多大的破坏性,他们都不能为了在法庭上弄清真相而分心。很少有个体,无论是公共的还是私人的,能承担得起这一代价。

另一方面,企业可能会因此浪费大量金钱,承受利润和收入损失带来的实际痛苦,从而表明谎言需要付出代价。

就投票机公司而言,康诺利指出,这些指控的矛头直指其品牌核心:准确性和可靠性。

“当你的核心商业模式遭受攻击时,诽谤诉讼可能是一条必经之路,”康诺利说。“这是恢复声誉的唯一方法。”一个极其重要的问题是,在保护其商业模式时,这些不太知名的公司能否在公开辩论中重塑其准确性和可靠性规则。

影射的余震

媒体研究公司ZIGNAL LABS的数据说明了各种未经证实的对DOMINION的指控是如何在网上持续传播的。

不受信任的行业

2003年,约翰•普洛斯在其位于多伦多的地下室创办了Dominion。约翰•普洛斯是加拿大人,在美国没有投票权,最近他卖掉了第一家初创公司(一家电信技术公司),从硅谷搬回了老家。

在2000年美国总统选举(该选举因蝴蝶选票和孔屑废票引发了争议)后,他有了一个大胆的创意。国会后来通过了《帮助美国投票法案》,主要是为了改善投票技术和保证投票无障碍性。普洛斯想建立一个系统,既能帮助盲人投票,同时又不违背选票保密性。

他以1920年加拿大《自治领选举法》(该法案赋予了女性选举权)为这家公司起名。“我们认为这是对帮助选民投票的人表达的一种崇高敬意,”普洛斯说。

视力不好的选民也可使用Dominion投票机,普洛斯逐步在各州和地方政府建立了广泛的客户群。他招募了一个专门负责完成公司民主使命的员工,若非如此,可能需要应对“大量的”工作时间和七天选举季工作周。

到2020年,Dominion成为美国第二大投票机公司,其投票机已在美国28个州和波多黎各进行的1,500次选举中使用,员工约300人。

但Dominion加入了一个已经饱受各政治派别质疑的行业。在推动投票技术现代化进程中,一些辖区已升级为电子系统,但其可追溯性并不透明,尤其是在投票机未留下任何纸质记录时。

2006年,政治接班人、环保专业律师及后来成为反疫苗活动家的小罗伯特•肯尼迪在《滚石》杂志上发表了一篇文章,质疑共和党是否在这些投票机帮助下“偷走了” 2004年选举结果。

2008年,普林斯顿大学计算机科学教授安德鲁•阿佩尔演示了如何用螺丝刀入侵投票机。

这种妄想促使人们重新采用更老套的方法。如今的大多数投票机,包括Dominion投票机,都会生成或统计可用于重新计票的纸质选票。

尽管如此,不信任危机仍在蔓延,尤其是在2016年总统选举期间,关于俄罗斯涉嫌干预选举的报道不断出现。(这种干预包括广泛散布谣言,但调查称并无任何证据表明投票系统被篡改。)

Dominion也未能免受怀疑:绿党总统候选人吉尔•斯坦因四年前在威斯康星州失利后,起诉要求审查威斯康星州使用的Dominion 投票机和其他投票机的源代码;该诉讼仍在进行中。

尽管存在这种不信任的背景,但若非因安特里姆县,2020年选举可能对Dominion并无任何影响。

密歇根州北部是共和党的大本营,但在大选之夜,截至当地时间周三上午,拜登及选票数低的民主党人似乎以压倒性优势获胜。竞选律师提请选举官员注意这一反常现象时,他们发现了问题:选票上的候选人发生了变化,但地方官员并未用新模板重新编程使用Dominion软件的一些投票机。结果,选民的投票在最初计票时基本上被调低了一行,其选票计入了另一政党的候选人名下。

在错误被发现当日,选举官员就纠正了这一人为错误;最终,特朗普赢得了安特里姆县。安特里姆县事件“表明问题和解决过程促成了正确的结果,”专门研究选举技术的无党派非营利组织OSET研究所的全球技术开发总监爱德华•佩雷斯说。

“但仍借此来指控选举被操纵,这令人难以置信。”

复核。凤凰城一名选举工作人员审核选票。亚利桑那州是调查人员寻找选票舞弊证据的其中一个州,但调查人员并未在此找到证据。今日美国网/路透社

但损失已经造成,阴谋论者仍心存疑虑。Dominion投票机已在一些竞争最激烈的州使用:密歇根州、佐治亚州和亚利桑那州等。

11月6日,在选举正式开始前,亚利桑那州共和党众议员保罗•戈萨尔以安特里姆县事件为例,开始在推特上呼吁“审查所有Dominion软件”的“巨大欺诈可能性”。调查呼声越来越高,而决心为选举结果而战的特朗普总统也乐于扩大其影响。

在鲍威尔和朱利安尼召开新闻发布会时,事情变得更加奇怪。

阴谋论贩子认为Dominion有一个邪恶的伙伴:委内瑞拉独裁者查韦斯,他于2013年去世。鲍威尔的这一说法在很大程度上是基于一份经过大幅修改的宣誓书,该宣誓书来自一位所谓的“委内瑞拉告密者”,他声称Smartmatic自己开发的软件能够偷偷篡改对查韦斯的投票,而Dominion的系统就是从该模型衍生出来的。

Smartmatic和Dominion都极力否认这种说法。但这种说法确实与现实有着扭曲的联系,因而会让那些愿意相信它的人听起来感觉更可信。Smartmatic的创始人是委内瑞拉人;美国外国投资委员会早在2006年就调查了该公司与委内瑞拉的关系;Dominion收购了Smartmatic几年前剥离的一家子公司。

这根纤细的稻草成了鲍威尔和朱利安尼打击Dominion的棍子。据Zignal称,社交媒体已超过11万次提及Dominion与委内瑞拉的关系。(至于Smartmatic,在美国2020年选举中,只有洛杉矶使用了其投票机。)

选举前后发生的一系列怪事件进一步催生了怀疑论。由于人们担心感染新冠肺炎,数以百万计的人缺席投票,这一情况前所未有,因此,投票结果很接近,再加上计票过程很长,致使全国选民都非常关注此次选举,政党律师和民调观察者都在努力让其支持的人取胜。

“就像觉得存放时间长的鱼有臭味一样,人们总会对原先的选举结果有所质疑,这已是老生常谈的事,”马克•布拉登说,他曾任RNC首席顾问,现就职于BakerHostetler(他称对Dominion的指控是“纯属虚构,完全是胡说”)。

再者,某总统花数月时间做铺垫,一旦竞选失败,就大声疾呼欺诈,阴谋论的时机已经成熟。

“这些指控的依据极易让人轻信,”一位共和党律师说。“Dominion很倒霉。”

尽管如此,鉴于安特里姆县的失误,Dominion投票机转移选票的理论最初似乎站得住脚,但当共和党官员前往拜登获胜的各州寻找证据时,谎言一下子就露馅了。

选举律师查理•斯皮斯代表有望取胜的共和党候选人约翰•詹姆斯参加了2020年密歇根州参议院席位竞选。如果安特里姆县的问题已涉及该州使用Dominion投票机的其他县,他的候选人就会获胜。

“我的目标是找到能够证明存在该问题并足以影响结果的证据,”斯皮斯说。他表示,他试图驳回鲍威尔提出的每一项指控,希望能有所帮助,但都落空了。

“对于这一惊天阴谋,我感到难以理解的是,这些投票机之间并没有互联,”他说。“一台投票机并不能改变全州的选举结果。”

全国各地的共和党竞选律师和候选人也在做着同样的事情。在亚利桑那州,州内外的律师们都在调查Dominion投票机,但经过近一周的苦苦寻找以及与技术人员和选举工作人员面谈,他们并没有发现任何统计异常、不当互联网连接,也没有发现任何其他问题。

在弗吉尼亚州,共和党官员和律师在11月19日召开的新闻发布会上听到朱利安尼说他们州存在选举欺诈,感到很惊讶,他们并没有从自己的民调观察者那里听到类似的消息。当他们要求特朗普竞选团队给出解释时,没有人作出回应。

如果存在不当行为,官员们认为不要求调查真是太奇怪了。“我们问他们掌握了哪些证据,但从未得到任何人的答复,”共和党竞选律师、竞选财务合规公司Election CFO创始人克里斯•马斯顿表示。“但让我们感到欣慰的是,弗吉尼亚州并没有普遍存在基于投票机的欺诈行为。”

鲍威尔自始至终都在通过媒体,同时也在幕后为自己辩护。竞选落败的共和党候选人称,他们接到鲍威尔和她的团队来电,敦促他们“继续战斗”,她“要打开一个缺口”,他们“最好参与进来”。

但当竞选律师要求提供证据时,“我们并未收到任何证据,只是了解了大概情况,‘太糟糕了,他们作弊,选举结果被偷走了,’”一位共和党律师说。“根本没有这回事,”另一律师说。

“气隙”

共和党人发现的或未发现的情况都恰恰是投票系统专家们所期望的。在科技含量较低的新时代,包括Dominion投票机在内的大多数投票机均设计成完全离线运行,并未连接互联网,用网络安全术语来说,它们是“气隙”的。

普林斯顿大学计算机科学家阿佩尔用螺丝刀入侵了一台投票机。他指出,目前至少有几种方法可以远程破坏这一新产物,通常涉及一个互联网接触点。一种是在投票机运出仓库之前安装恶意软件,如通过对Dominion员工进行网络钓鱼攻击。

另一种方法是破解县政府官员用来为地方一级投票机编程的笔记本电脑,这通常要将选票数据上传到存储卡或U盘,并通过添加欺诈算法来向投票机传输数据。如果成功的话,这些投票机可能会被“以联网方式入侵,一次入侵可以涉及数千台投票机,”阿佩尔说。

不过,未来的黑客们仍面临着巨大的障碍。

其一,按照目前的做法,即使是编程用笔记本电脑,除极少数失误外,也无法连接到互联网,这使得远程黑客几乎无法访问。

其二,即使攻击者确实在投票机上安装了欺诈性的投票切换软件,在选举前投票机进行各种认证和准确性测试中,或者在某些州进行选举后审查中,它也会被发现。

“在很多地方,搞破坏的人必须一次又一次地逃避检测,”OSET的佩雷斯解释说。最后,如果纸质选票与投票机计票结果相符, 2020年重新计票的各州就属于此种情况,“就是投票电脑未被黑客入侵的有力证据,”阿佩尔说。

换句话说,倘若发生鲍威尔和朱利安尼所述的黑客攻击,该攻击在2020年就已经被发现了。从11月到次年1月,手工重新计票已涵盖超过1,000台Dominion投票机,包括对佐治亚州500多万张选票进行的第三次重新计票。并没有发现任何重大的错误或违规行为。

选举后不久,有关更世俗指控的法律质疑就土崩瓦解了,其他律师事务所不再接手特朗普竞选事宜,竞选法律战略和法律投诉事宜就落到了朱利安尼和鲍威尔等盟友的手中。鲍威尔以擅长上诉诉讼而闻名,她有着丰富的法律经验和敏锐的洞察力。

但是,鲍威尔和她的团队提交的有关Dominion诉讼案情摘要的证据,就像是由一些无关新闻组成的大杂烩。一些文件将下载到运行Dominion软件的笔记本电脑上的一款电脑游戏作为潜在黑客攻击的证据;一些文件则将异常高的投票率作为可疑的证据。在一些证词中,证人解释说,他们的证词来自在谷歌搜索中找到的资讯。

12月,亚利桑那州的一名法官完全驳回了鲍威尔提起的一项诉讼,她认为:“以公众谣言和影射为依据的指控不能取代联邦法院严肃认真的辩护程序。”

评论者认为,鲍威尔及其盟友在法庭和媒体上公布对Dominion不利的证据,充其量只能证明存在确认偏差,即阴谋论者将一次违规行为作为阴谋的证据,但这并不能类推。

换句话说,仅仅因为一台投票机可能被黑客攻击并不表示它会产生明显影响,马克•布莱登最近发现自己已对此做了很多解释。

布拉登,RNC的前首席律师,在他的职业生涯中已经处理了约100起重新计票事件,他认为,这一数量比国内任何其他共和党律师都多。最近,党内其他人一直打电话向他询问Dominion指控事宜,他一直在极力回避。

“他们认为,‘哦,这么多烟,一定是哪里着火了。’”布拉登说。“而实际情况是,每个人心中都有疑虑。这不是烟,这些只是令人迷惑的云雾。”

截至2020年圣诞节,特朗普竞选团队及其同僚提起的50多起选举不当诉讼均被驳回,法律和网络安全机构也越来越不关心有关Dominion的故事。

在12月卸任前,司法部长威廉•巴尔表示,经过联邦调查,“到目前为止,我们尚未发现可能会影响选举结果的大规模欺诈行为。”

3月,美国司法部与国土安全部网络安全和基础设施安全局共同解密了一份联合报告,该报告涉及“一个或多个外国政府”控制投票机和操纵计票的“多项公开指控”。报告称,经过调查,这些机构“认定这些政府不可信。”

事实、观点和新闻

去年秋天,普洛斯收到了许多恐吓信和死亡威胁,此外,还收到了来自纽约长岛一位希腊东正教牧师的一条意外消息。牧师猜中了普洛斯所属的教派,并表示愿意提供支持。他们从未谋面,但已交谈数次,牧师给普洛斯寄了一些有关精神和历史领域的书籍。

“我们曾谈到这并不是历史上第一次发生的不公平事情,看来没希望了,”普洛斯回忆道。“他一再提醒我,事实上,我们站在历史正确的一边。”

在一次心理咨询会上,牧师用温斯顿•丘吉尔的话宣泄了一下情绪:“如果你正在经历地狱,继续前进。”对于普洛斯和他的员工来说,这句名言现在成了箴言。

Dominion的反击已经达到了一定的预期效果。11月和12月,Dominion和Smartmatic分别就福克斯新闻宣传的指控向其发出了警告信。此后,福克斯新闻针对这些指控进行了“事实核查”,还采访了OSET的佩雷斯,结果发现并没有这种事。

鲍威尔、朱利安尼以及这个故事本身从一月初开始就基本上在该新闻网消失了。

然而,该故事仍在保守派媒体和社交媒体上传播,普洛斯和他的同事说,损害仍未停止。

作为一家私人控股公司,Dominion并未披露其财务状况,但其对福克斯提起的最新诉讼列举了其声称遭受的一些损害,包括预期在俄亥俄州和路易斯安那州进行的投票机交易,这些交易自选举以来已被搁置。

该公司要求赔偿的损失包括6亿美元利润损失、至少10亿美元企业价值损失以及数十万美元安全和“打击谣言运动”费用。尽管索赔金额之高令人震惊,但Dominion的律师克莱尔对此进行了辩护。

“在我从业25年来,此类消息波及的范围以及听到这一消息、相信这一消息并付诸行动的人数都是前所未有的。”

Dominion和Smartmatic的律师知道,为了胜诉,这还不足以证明这个弥天大谎并非事实。因为从法律角度看,两家公司可能会被视为“公众人物”(公司几乎总是这样),所以要以更高的标准来证实这明显是诽谤:他们需要证明存在真实恶意,即虚假信息散布者故意撒谎或不顾后果地无视事实真相。

也就是说,在现实和“另类事实”不相容时代,审判可能会引发一个尤为紧迫的问题:相信虚假说法是否属于不计后果地无视事实?

摘自美国Dominion公司、Dominion投票系统公司以及Dominion投票系统集团诉福克斯新闻网络有限责任公司案

被告在Dominion案件中的回应以不同的方式反映了这一问题。

迄今为止,鲁迪•朱利安尼一直在Dominion和Coomer提起的诉讼中进行自辩,但他没有回应置评请求,他提交的法庭文件也几乎未透露他的策略。

MyPillow的CEO迈克•林德尔尚未在法庭上对Dominion作出回应,但他表示,他计划将其索赔金额加倍。林德尔说,他收到了“确凿证据”,他计划在后续的证据公示中公开该证据,但他并未允许《财富》查看该证据。

“我们将用历史上最大一起《第一修正案》诉讼来反诉他们,”他说,并补充道,“如果你说的是某人的真相,就不是诽谤。”

西德尼•鲍威尔在3月底对Dominion的诉讼作出回应,提出了驳回诉讼的动议。

她在诉讼摘要中提出的其中一个论点极具挑衅性:即使她的声明可被证明真伪,诉讼摘要写道,“任何理智的人都不会认为,这些声明是真实的事实陈述。”

在某种程度上,这让诽谤专家感到困惑,因为这似乎削弱了鲍威尔的权威。《第一修正案》律师、耶鲁法学院信息社会项目的高级研究员桑德拉•巴伦认为,这一目标不太可能实现:“在我看来,这种辩护对惊人杂谈节目主持人来说是最好的猛料——‘没有人把我们说的话当真,’”巴伦说。

“但我认为这对律师来说是一个有力论点。”鲍威尔的律师霍华德•克林亨德勒在接受《财富》采访时澄清了这一观点。他认为,鲍威尔的公开声明并非事实,但在她出示其他人(她认为的专家证人)的证词时,可形成意见。

克林亨德勒承认,这些证人的证词可能站不住脚,但他说,不应凭此认为他们的论点无效,或指责鲍威尔。“这些专家报告并非一派胡言,他们有文件、截图和分析为据。”克林亨德勒说。

他和鲍威尔曾希望,且现在仍然希望他们的文件足以“证明”有必要在法庭上公开更多证据。

媒体法律资源中心执行主任乔治•弗里曼,曾长期担任《纽约时报》的诽谤诉讼辩护律师,他说,这种观点犯了“最基本的错误”。

“那些被披露的事实必须属实,”他说。如果不属实,“辩护就会土崩瓦解。”(鲍威尔在法庭上也可能会被责难,因为她把这些“意见”说成是事实。例如,12月初,在卢•多布斯同名的福克斯商业黄金时段节目中,她对主持人说:“如果你不了解事情的原委,你就会像傻瓜一样,愚蠢得要命,因为任何人都愿意看到真凭实据。”)

事实与观点的区别,以及谁对前者的准确性负责,必然是对福克斯新闻诉讼的主题,无疑是投票机诉讼中最重要的部分。

律师们说,无论结果如何,这些案件都会在新闻界掀起涟漪,重新定义各组织在报道和纠正谣言方面的作用。

截至本文发表,福克斯尚未对Dominion提起的诉讼作出回应,但对Smartmatic诉讼的回应让我们对其策略有了一定了解。(福克斯新闻拒绝让工作人员就此接受采访。)

福克斯新闻在Smartmatic案件中辩称,特朗普总统发起的选举质疑具有“无可否认的新闻价值”,而且是“公众关注的问题”——法律给予此类言论更大保护。

“如果《第一修正案》有效,福克斯就不为公平报道和评论在激烈竞争和积极诉讼的选举中发生的竞争性指控负责,”福克斯在一份声明中说。福克斯还指出了其播出的“事实调查部分”,此外,其电视台工作人员也表示,没有证据表明存在广泛欺诈行为。

弗里曼称,福克斯似乎以中立报道为策略进行辩护,即新闻媒体可报道和重申责任人提出的重要主张。许多人认为媒体应该拥有这一权利,弗里曼也是其中之一。

然而,很少有法院承认中立报道这一特权,而且在福克斯的总部所在地纽约(Smartmatic起诉地),法院不承认这一特权。

律师们说,即使法院承认,福克斯仍有可能在中立问题上摔跟头。毕竟,陪审团必须考虑其全部报道内容以及其是否赞同嘉宾的观点。

承认这一特权促使Dominion和Smartmatic提起诉讼。例如,11月,多布斯与鲍威尔讨论完Dominion有关事宜时,称他“很高兴”鲍威尔正在“努力解决这一切。这是一个肮脏的烂摊子,而且比我们任何人想象的都要险恶得多。”(福克斯在2月Smartmatic起诉后第二天取消了多布斯的节目,但该电视台称,取消节目与诽谤案无关。)

如果福克斯败诉,Dominion和一些主流评论员可能会为这场胜利欢呼,会称其为企业对抗谣言的胜利,是事实与替代事实之间的界限,也可能成为未来诉讼的标准。

耶鲁大学的巴伦说,小心事与愿违。遏制虚假新闻(如果你愿意那样的话)实际上可能会对新闻自由和言论自由总体上产生寒蝉效应。

“希望这只会让那些有可能在诽谤诉讼中败诉的人感到寒意。”她说。“我认为,不管好坏,在这场诉讼中,美国可能会有机会了解许多关于诽谤法的限制。”

除《第一修正案》之外,还可依据其他法律追究这一弥天大谎散布人的责任。鲍威尔和朱利安尼以及其他几位提出选举质疑的律师,正遭到政府官员起诉,意在彻底取消其律师资格。

一些散布鲍威尔和朱利安尼等言论并采取行动的立法者正被一些资助者惩罚:多家公司已不再为拒绝证明2020年选举有效性的立法者的竞选活动提供经费。

还有一个问题是,Dominion的诉讼推进是否足够快、足够深远,从而能够产生影响。

具有讽刺意味的是,Dominion的说法中作为例证的不利信息可能会使人们更加难以了解真相。一旦进入审判阶段,聘请足够多未受充斥各处的指控影响的陪审员可能是一大挑战。

任何最终裁决可能需要三到四年才能做出,也就是说,在裁决证实投票机公司无罪之前,可能还会举行一次总统选举。如果Dominion胜诉,这一结果是否会影响信仰阴谋论的数百万人,尚不得而知。

对普洛斯来说,有关诚信和民主的问题远比这些担忧重要。他说,Dominion目前自己支付律师费,有足够的财力应对持久诉讼,并不打算和解。

“在真相未揭晓前,我们不会提出和解。”他说。“我们对此并不感兴趣。”与此同时,普洛斯和他的同事们接受了另一项使命:向美国选民解释选举程序。只要大多数辖区都使用纸质选票,选举专家预计,甚至是少数持反对意见的人最终也会采用纸质选票,人们就比较容易心安。

Dominion高管尼科尔•诺莱特已将消除谣言作为首要任务。“你不必相信我们的话,”她一再地解释道。若无明显证据:“你可以手工重新统计纸质选票;你也可以用投票机重新统计选票,”她说。

今后,更多州可能会这样做,这可能是在阴谋论蔓延之前消除阴谋论的一种更有效的方式。(财富中文网)

译者:Min

ON DEC. 9, NICOLE NOLLETTE, an executive at Dominion Voting Systems, was driving home from a doctor’s appointment when she noticed she’d missed a call from one of her customers.

The client, an elections official whose jurisdiction uses Dominion’s voting machines, had also sent her a link to a website. Nollette pulled up the site on her phone and saw her own photo—overlaid with bright red crosshairs, as though she were in the sights of a sniper’s rifle. The website, which bore the moniker “Enemies of the People,” also included an address in Nevada, showing aerial views of that property beneath Nollette’s picture. That alarmed Nollette even more, because she doesn’t live in Nevada but in Colorado, where Dominion is based. The address was for the home of her retired parents. Months later, the Navy veteran remembers the fear in her mother’s voice over the phone as her parents loaded the website: “They have a picture of the house,” her mom gasped.

Nollette was one of more than a dozen people, ranging from other Dominion employees to Trump administration officials, whose photos were posted on the website. The site accused them all of playing a role in an elaborate conspiracy to rig November’s presidential election by “flipping” votes for Donald Trump to Joe Biden—and relying on Dominion’s machines, which are in use in 28 states, to do it. Later that day, the FBI showed up on Nollette’s parents’ doorstep to alert them to the menace. Soon, Nollette herself received death threats—including one sent to her personal email address, warning, “Your days are numbered.” She still doesn’t know who sent them, though the FBI later notified Dominion and others that its intel had linked the hit list to Iran.

The threats have tapered in the months since President Trump left the White House. But Nollette, who lives alone, still watches for suspicious cars around her street. And while she once made a daily habit of taking walks before sunrise and after sunset, she now goes out only in the light of day. “This is the first time since I left the military that, at least in terms of security and threats, I’ve had to engage that military training,” she says.

Nollette’s life is one of many upended by perhaps the mother of all conspiracy theories: a farfetched but pernicious tale spun up in a lastditch attempt to overturn the outcome of the presidential election. It’s a tale that found its roots in a rat’s nest of misinformation and which has come to be known, among many who have encountered it, as the Big Lie. Judges, election officials, cybersecurity experts, and governors have been publicly badgered for discrediting it, or vilified for failing to prove it. Others have faced Nollette’s fate, or harassment still more severe. Eric Coomer, Dominion’s director of product strategy and security, was doxed by one of the theory’s espousers about a week after the election. A mountain climber and breadbaker with a Ph.D. in nuclear physics, Coomer has not been able to return home since the threats began and is hiding somewhere outside the U.S.; even his lawyer doesn’t know where he is.

The Dominion narrative drew oxygen from various corners of the Internet and conservative political spheres. Trump himself tweeted on Nov. 12 that Dominion “deleted” 2.7 million of his votes. But it passed a point of no return on Nov. 19. That’s when Rudy Giuliani, the former New York mayor, and Sidney Powell, an appellate lawyer and a onetime federal prosecutor, both then representing the Trump campaign, held a press conference at the Republican National Committee headquarters in Washington to focus on “legal challenges” to the election results.

Up until that day, Dominion might have been able to mount a defense with a factchecking campaign aimed at correcting the record; it had hired crisis PR specialists as well as a top physical and cybersecurity firm. “It never really dawned on me that these people had ruined our company,” says John Poulos, Dominion’s cofounder and CEO. But he felt his world tilt as he watched the press conference unfold.

Some 25 minutes into the event, Giuliani mentioned Dominion for the first time—just around the memorable moment that his hair dye began streaming down his face. He later singled out Coomer by name, calling him a “vicious, vicious man” who was “close to Antifa.” Giuliani and Powell went on to allege that Dominion’s software had been built in Venezuela under orders of dictator Hugo Chávez for the purpose of fixing elections, and that it counted votes in Germany and Spain—claims that were easily disproved, but were red meat to partisans convinced that the GOP had been victimized.

“It was just a surreal moment,” says Poulos, who was at home in Toronto with his wife, three teenagers, and two dogs. “I thought that they were working to incite a civil war.”

Earlier that month, Powell had promised to release the “Kraken,” a monster of Norse lore that was her metaphor for evidence of widespread voter fraud. That evidence, according to authorities ranging from the Department of Justice to Republican election attorneys, has yet to be delivered. What Powell and Giuliani unleashed instead was a barrage of misinformation that embedded shrapnellike shards of doubt in the walls of democracy. In the days after the press conference, Giuliani and Powell would repeat their claims about Dominion many more times on rightleaning cable networks, including the most popular of all, Fox News, which last year commanded more than 3.5 million nightly prime time viewers. Other sources far less reputable or official picked up the story and ran with it: According to Zignal Labs, which tracks opinion trends across media, Dominion has been mentioned in reference to rigging the election more than 400,000 times on Twitter, YouTube, and other social media. Dominion for countless Trump supporters quickly became a name synonymous with suspicion and scandal.

The Dominion narrative became one of the thickest clouds in a fog of calumny around the election. In the two weeks after the Associated Press called the race for Biden, Fox News either questioned or put forth conspiracy theories about the results at least 774 times, according to Media Matters, a nonprofit that tracks right leaning misinformation. A survey around the same time by researchers from universities including North eastern found that more than half of Republican voters either thought Trump had won or weren’t sure who did. Poulos’s own uncle, in Arizona, believes Dominion played some role in a conspiracy. “He doesn’t know what parts to disbelieve,” Poulos says.

The consequences played out in unspeakably tragic form on Jan. 6, when a mob, made up predominantly of those who believed the election was stolen, broke into the U.S. Capi tol in a riot that left five people dead.

Two days later, Dominion filed its first defamation lawsuit. Poulos had decided to litigate not long after the November press conference. “The only remedy that we have is by taking their case to court,” he says. “The truth absolutely needs to come out.”

*****

Accidental Plaintiffs

IN THE CHAOS of the nation’s corrosive election dispute, it was easy to miss the significance of the attacks on Do minion. When Trump backers spread general (if largely baseless) rumors about widescale ballot and voter fraud, their allegations were easily defensible as free political speech. But when Powell and Giuliani pointed the finger at Dominion, they crossed a crucial line. Now the operatives were making specific claims about a specific party, in ways that were economically damaging. And because those claims were quickly discredited—including in investigations by GOP election operatives who had every motive to hope they were true—the speakers’ insistence on repeating them would seem, legally, to demonstrate “actual malice,” or reckless disregard for the truth.

“If they meet all of those elements, then you can hold people account able, regardless of the fact that it is in the context of the political process,” says attorney Tom Clare. Clare has not lost a defamation trial since founding his libelfocused law firm, Clare Locke, seven years ago; now he’s representing Dominion.

On Jan. 8, Dominion filed a defamation case against Powell. Over the next few weeks it filed similar suits against Giuliani and Mike Lindell, the CEO of MyPillow, who has released hourslong videos rife with conspiracy theories starring Dominion; each suit requests damages of $1.3 billion. The company filed its fourth suit on March 26 against Fox News, asking for a judgment of more than $1.6 billion. (Dominion’s is the second big defamation case Fox is facing based on its coverage of voting machines: In February, Smartmatic— a competitor to Dominion with considerably smaller U.S. operations—sued Fox for $2.7 billion.) It’s a historymaking tornado of litigation, legal experts say, for the volume of claims against multiple defendants around the same issue. “That is, in my experience, unique,” says J. Erik Connolly, Smartmatic’s attorney, who successfully sued ABC News for its “pink slime” coverage on behalf of a beef company in the biggest defamation suit on record. “From a reputational damage perspective, it’s a perfect storm.”

The cases are also potentially groundbreaking in a more significant way, one whose ramifications are impossible to predict: They’re an effort by private companies to make other parties literally pay for abusing political discourse—including a media giant that has had a huge influence on 21stcentury public life. Fox argues that the votingmachine allegations were inherently news worthy, and that the airtime it gave them is protected under the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. The plaintiffs argue that the falsity of the allegations, and the apparent endorsement of them by some Fox hosts, strips those protections away.

Companies are positioned to con duct this fight in a way that individuals rarely are. Politicians seldom sue for defamation, especially in the heat of a campaign. No matter how dam aging the rumors spread by an opponent, they can’t afford the distraction of hashing out the truth about their past in court. And few individuals, public or private, can afford the cost. A business, on the other hand, can bring deeper pockets to the battle— and can point to the tangible pain of lost profit and revenue to show that untruths have consequences.

In the case of the voting machine companies, Connolly points out that the allegations took aim at the very heart of their brands: accuracy and reliability. “When you have an attack like that on your core business model, a defamation lawsuit may become a business necessity,” Connolly says. “It’s one of the only ways you can restore your reputation.” The multibilliondollar question is whether, in protecting that business model, these relatively obscure companies can reshape the rules around accuracy and reliability in public debate.

******

The Aftershocks of Innuendo

THIS VISUALIZATION OF DATA FROM MEDIA-RESEARCH FIRM ZIGNAL LABS SHOWS HOW VARIOUS UNSUBSTANTIATED CLAIMS ABOUT DOMINION PERSISTED ONLINE.

*****

A Distrusted Industry

JOHN POULOS started Dominion out of his basement in Toronto in 2003. A Canadian who doesn’t even vote in the U.S., he’d recently moved back home from Silicon Valley after selling his first startup, a telecom technology company. He found his next big idea in the aftermath of the 2000 U.S. presidential election, with its controversies over butterfly ballots and hanging chads. Congress had subsequently passed the Help America Vote Act focused on improving voting technology and accessibility. Poulos had an idea for creating a system that would help blind people vote without compromising the secrecy of their ballots. He named the company after Canada’s Dominion Elections Act of 1920, which expanded women’s suffrage. “We thought that would be a nice homage to helping voters vote,” Poulos says.

Dominion voting machines could also be used by sighted voters, and Poulos gradually built a clientele among state and local governments. He recruited a staff dedicated to the company’s democratic mission, if not the “obscene” hours and sevenday election season workweeks. By 2020, Dominion was the secondlargest votingmachine business in the United States, with its machines used in 1,500 elections in 28 states and Puerto Rico, and a staff of about 300.

But Dominion had joined an industry that was already viewed with suspicion from across the political spectrum. In the push to modernize voting technology, some jurisdictions had upgraded to electronic systems whose traceability was opaque— particularly in cases in which machines left no paper records. In 2006, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the political scion, environmental attorney, and future antivaccination activist, published an article in Rolling Stone questioning whether the 2004 election had been “stolen” by the GOP with help from such machines. In 2008, a Princeton University computer science professor named Andrew Appel demonstrated how to hack certain voting machines using a screwdriver.

The paranoia helped set off a rollback to more oldschool methods; most machines today, including Dominion’s, generate or tally paper ballots that can be recounted. Still, mistrust kept percolating, particularly after reports of Russian interference dogged the 2016 presidential elections. (That meddling included extensive misinformation campaigns, but investigations found no evidence of votingsystem tampering.) Dominion wasn’t immune from the suspicion: Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein sued to review the source code of Dominion and other machines in Wisconsin after her loss there four years ago; that litigation is ongoing.

Despite that backdrop of distrust, the 2020 election might have unfolded with little drama for Dominion—if not for Antrim County. That northern Michigan jurisdiction is a Republican stronghold, but on Election Night, and as the vote was counted into Wednesday morning, Biden and downballot Democrats appeared to be winning by a landslide. When campaign attorneys brought the anomaly to election officials’ attention, they discovered the problem: There had been a change in the candidates listed on the ballot, but a local official had neglected to reprogram some of the machines—which used Dominion’s software—with the new template. As a result, voters’ selections were essentially transposed down a row in initial tallies, their votes accruing to another party’s candidate.

Election officials corrected the human error the same day it was caught; in the end, Trump was the clear winner in Antrim. Antrim “shows that the problems and process leads to the correct result,” says Edward Perez, global director of technology development for the OSET Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit focused on researching election tech. “It seems a strange circumstance to pick on to show how the election was rigged.”

The damage, however, was done, and conspiracy theorists had a kernel of doubt to run with. Dominion’s machines were in use in some of the most closely contested states: Michigan, Georgia, and Arizona, to name a few. On Nov. 6, before the election was officially called, Rep. Paul Gosar, an Arizona Republican, citing the Antrim incident, began tweeting calls to “audit all Dominion software” for its “massive fraud potential.” Calls for investigations grew louder, and President Trump, determined to fight the election results, was happy to amplify them.

By the time Powell and Giuliani held their press conference, things had taken a more outlandish turn. Conspiracymongers had assigned Dominion a partner in evil: Venezuelan strongman Chávez, who had died in 2013. Powell’s narrative relied significantly on a heavily redacted affidavit from a supposed “Venezuelan whistleblower” who alleged that Smartmatic had built its software to be able to secretly change votes to Chávez, and that Dominion’s system descended from that mold. Both Smartmatic and Dominion vigorously dismiss that narrative. But the story did have a distorted, gameofTelephone connection to reality that helped it sound more plausible to those inclined to believe it. Smartmatic’s founders were Venezuelans; the federal Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. probed the company’s ties to Venezuela back in 2006; and Dominion had bought a former subsidiary of Smartmatic’s several years after Smartmatic divested it. That thin reed turned into a stick that Powell and Giuliani beat Dominion with. Dominion’s ties to Venezuela have garnered more than 110,000 social media mentions, according to Zignal. (As for Smartmatic, in the 2020 election in the U.S., the only place where its machines were used was Los Angeles.)

The bizarre conditions around the election provided particularly fertile ground for skepticism. The combination of a close result and a long votecounting process—caused by the unprecedented millions who cast absentee ballots owing to COVID19 concerns—created a tense nationwide spectator sport, with party lawyers, poll watchers, and armchair detectives seeking paths for their guy to eke out a win. “It’s the old cliché: Old fish and old election results smell, because people get suspicious about them,” says Mark Braden, a former chief counsel to the RNC who’s now at the firm BakerHostetler (and who calls the claims against Dominion “fantasyland, total garbage, 100%”). Add a President who had spent months laying the groundwork to cry fraud if he lost, and the climate was ripe for conspiracy theories. “The base is very credulous on these sorts of accusations,” says a Republican attorney. “And Dominion drew the short straw.”

Still, while the theory that Dominion machines were flipping votes might have initially seemed to hold water in light of the Antrim County bungle, the bottom fell out as soon as GOP officials went looking for proof in states that Biden won. Charlie Spies, an election law attorney, represented Republican hopeful John James in the 2020 Michigan Senate race. If the Antrim County glitch had carried over into the other counties using Dominion machines in the state, his candidate would have won. “My goal was to find evidence of a problem large enough to have impacted the results,” says Spies. He says he tried to run down every claim raised by Powell, hoping it would help, but all came up short. “Where I get lost on the big conspiracy is, these machines aren’t interconnected,” he says. “And one machine doesn’t change a statewide election.”

Republican campaign attorneys and candidates across the country were trying to do the same thing. In Arizona, lawyers from both in and out of state descended to investigate Dominion’s machines, but after nearly a week of digging and interviewing technicians and election workers, they found no statistical anomalies, improper Internet connections, nor any other problems.

Over in Virginia, Republican party officials and attorneys were surprised to hear Giuliani reference fraud in their state during the Nov. 19 press conference; they had heard nothing of the sort from their own poll watchers. When they followed up with the Trump campaign, no one got back to them. If there were examples of malfeasance, the officials thought it was odd not to be asked to investigate them. “We could never get anyone to tell us what proof they had,” says Chris Marston, a Republican campaign attorney and founder of Election CFO, a campaignfinance compliance company. “But we feel comfortable there was no widespread machinebased fraud in Virginia.”

All along, Powell was making her case, both in the media and behind the scenes. GOP candidates who’d lost their races say they were fielding calls from Powell and her team, urging them to “keep on fighting,” that she was “going to break this wide open” and that they’d “better get on board.” But when campaign lawyers asked for evidence, “we’d never get anything back other than general, ‘It’s bad, they cheated, it was stolen,’ ” says a Republican attorney. “There’s no ‘there’ there,” says another.

******

“Air-Gapped”

WHAT THE Republican operatives were—or weren’t—finding was exactly what experts in voting systems expected. In the new, lowertech era, most voting machines including Dominion’s are designed to operate fully offline, with no connection to the Internet—they’re “airgapped,” to use the cybersecurity term. Appel— the Princeton computer scientist who has hacked a voting machine with a screwdriver—notes that there are still at least a couple of ways to compromise the new breed remotely, generally involving a touchpoint to the Internet. One would be to install malicious software on the machines before they’re shipped out from warehouses, such as through a phishing attack on a Dominion employee. Another way would be to hack the laptops that county officials use to program the machines at a local level, which typically involves uploading the ballot data to a memory card or thumb drive and transferring that—with the addition of a fraudulent algorithm—to the machines. If pulled off successfully, the machines could be “hacked in a networked way, where one hack covers thousands of machines,” Appel says.

Still, wouldbe hackers face formidable obstacles. One is that under current practice, even the programming laptops are, except in rare lapses, not connected to the Internet, making them virtually inaccessible to a remote hacker. Second, even if an attacker did install fraudulent voteswitching software on machines, it’s extremely unlikely that it would escape discovery during the various certification and accuracy testing protocols the machines undergo ahead of an election, or in the postelection audits that certain states conduct. “There are many, many places where a bad actor would have to maintain the lack of detection, again and again and again and again,” explains OSET’s Perez. And at the end of the day, if the paper ballots match the machine tallies—as they did in the states that conducted 2020 recounts—“that’s pretty strong evidence that the voting computers weren’t hacked,” says Appel.

If a hack like the one Powell and Giuliani were describing were to take place, in other words, 2020 is the year it would have been caught. Be tween November and January, there have been hand recounts of votes involving more than 1,000 Dominion machines—including the third recount of Georgia’s 5 millionplus ballots. None found errors or irregularities on any meaningful scale.

As legal challenges regarding more mundane allegations fell apart soon after the election, other law firms dropped the Trump campaign as a client—consolidating the campaign’s legal strategy, and its legal complaints, in the hands of Giuliani and allies like Powell. Powell had built a reputation for her expertise in appeals litigation; she didn’t lack for legal experience or acumen.

But the evidence that Powell and her team attached to legal briefs in suits related to Dominion often reads like a hodgepodge of disconnected headlines. Some documents cite a computer game found downloaded onto a laptop running Dominion software as evidence of potential hacking; others point to unusually high voter turnout numbers as proof of something fishy. In some affidavits, witnesses explain that they are basing their testimony on things they found in Google searches. In December, when an Arizona judge dismissed one of Powell’s cases in its entirety, she concluded, “Allegations that find favor in the public sphere of gossip and innuendo cannot be a substitute for earnest pleadings and procedure in federal court.” To critics, the evidence Powell and her allies have aired against Dominion, both in court and in the media, is at best an illustration of confirmation bias—conspiracy theorists citing oneoff irregularities as proof of that conspiracy, without connecting any dots.

Put another way, just because a voting machine could be hacked doesn’t mean it was—a distinction that Mark Braden finds himself explaining a lot lately. Braden, the former chief counsel to the RNC, has worked on roughly 100 recounts in his career, more, he thinks, than any other Republican lawyer in the country. He’s recently been fielding calls from others in the party wondering about the Dominion allegations, and he’s been trying to shoot them down. “They think, ‘Oh, there’s so much smoke, there must be some fire,’ ” Braden says. “And the answer is, everyone just has clouds in their mind. It’s not smoke—these are just clouds of confusion.”

By Christmas of 2020, more than 50 lawsuits from the Trump campaign and its associates alleging election improprieties had been dismissed—and the legal and cybersecurity establishments had increasingly shrugged off the Dominion story. Before leaving office in December, Attorney General William Barr said that after federal investigations, “to date, we have not seen fraud on a scale that could have effected a different outcome in the election.” In March, the DOJ along with the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) declassified a joint report that addressed “multiple public claims that one or more foreign governments—including Venezuela, Cuba, or China” controlled voting machines and manipulated vote counts. Upon investigation, the report said, the agencies “determined that they are not credible.”

*****

Fact, Opinion, and News

AMID ALL THE HATE MAIL and death threats last fall, Poulos received an unexpected message from a Greek Orthodox priest in Long Island, N.Y. The priest had correctly guessed Poulos’s denomination and reached out to offer support. The men have never met, but they’ve spoken a handful of times, and the priest has sent Poulos books, from the spiritual to historical. “We’d have these conversations about how this is not the first time in history that something unfair has happened, and it seems hopeless,” Poulos recalls. “And he kept reminding me that in truth, we are on the right side of history.” A catharsis came in one of the counseling sessions, when the priest quoted Winston Churchill: “When you’re going through hell, keep going.” For Poulos and his employees, that phrase is now a sort of mantra.

To a certain degree, Dominion’s pushback is already having its desired effect. In November and December, both Dominion and Smartmatic sent warning letters to Fox News about the allegations the network was airing. After that, Fox ran some “factchecking” segments including an interview with OSET’s Perez debunking the claims. Powell, Giuliani, and the story itself have largely receded from the network since early January.

The story continues to ricochet around conservative media and social media, however, and Poulos and his colleagues say the damage endures. Dominion, as a privately held company, does not disclose its finances, but its latest lawsuit against Fox enumerates some of the harm it claims to have suffered, including anticipated votingmachine deals in Ohio and Louisiana that have been put on ice since the election. The damages the company is requesting include $600 million in lost profits, as well as lost enterprise value of at least $1 billion, along with hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on security and “combatting the disinformation campaign.” Although the many zeroes have raised some eye brows, Clare, Dominion’s attorney, defends the calculations. “The scope and the reach and the number of people that heard this and believed it and acted upon it is something that is just unprecedented in the 25plus years that I’ve been doing this.”

To win in court, Dominion’s and Smartmatic’s lawyers know it won’t be enough to prove the Big Lie isn’t true. Because the companies will likely be considered “public figures” in the eyes of the law (corporations almost always are) there’s a higher bar to clear to show defamation: They’ll need to prove the presence of actual malice—that the speaker of the false information either lied knowingly or with a reckless disregard for the truth. That means the trial could turn on a question that’s particularly urgent in an age of incompatible realities and “alternative facts”: Does putting trust in a false narrative count as reckless disregard for truth?

The defendants’ responses in the Dominion cases refract this question in different ways. Rudy Giuliani, who has so far represented himself in suits by Dominion and Coomer, did not respond to requests for comment, and his court filings to date give little indication of his strategy. Mike Lindell, the MyPillow CEO, has yet to respond to Dominion in court, but he says he plans to double down on his claims. Lindell says he received a “smoking gun” that he aims to release as part of a later evidence dump, though he declined to let Fortune review it. “We’re going to countersue them with the biggest First Amendment lawsuit in history,” he says, adding, “It’s not defaming if you’re telling the truth about somebody.”

Sidney Powell responded to Dominion’s lawsuit in late March with a motion to dismiss. One of the arguments in her brief is particularly provocative: Even if her statements could be proved true or false, it reads, “no reasonable person would conclude that the statements were truly statements of fact.” On one level, that puzzles defamation experts because it seems to undermine Powell’s authority. Sandra Baron, a First Amendment attorney and a senior fellow at the Information Society Project of Yale Law School, thinks it’s a long shot: “The last I looked, that defense worked best for a group of shock jocks—‘nobody takes what we’re saying seriously,’ ” Baron says. “But I think that’s a hard argument for a lawyer to make.” In an inter view with Fortune, Powell’s lawyer, Howard Kleinhendler, clarifies the argument somewhat. Powell’s public statements weren’t facts, he argues, but became opinions when she presented testimony of other people she judged to be expert witnesses. Kleinhendler acknowledges that those witnesses’ credentials could have been flimsy, but says that by itself shouldn’t disqualify their arguments, or put Powell at fault. “These expert reports weren’t just idle chatter—they were supported by documents, by screenshots, by analyses,” Kleinhendler says. He and Powell had hoped—and still hope—their documents would have been enough to “warrant discovery” of additional evidence in court.

There’s a “very basic mistake” in that argument, says George Freeman, executive director for the Media Law Resource Center who was a longtime libel defense attorney at the New York Times. “Those disclosed facts have to be true,” he says. If they aren’t, “the defense falls apart.” (Powell may also be taken to task, in court, for the vehemence with which she framed those “opinions” as facts. On Lou Dobbs’s eponymous Fox Business primetime show in early December, for example, she told the host, “You would have to be a damn fool and abjectly stupid not to see what happened here, for anybody who’s willing to look at the real evidence.”)

The distinction between fact and opinion, and who’s responsible for the accuracy of the former, are bound to be the main themes of the suits against Fox News—undoubtedly the most consequential pieces of the votingmachine litigation. Whatever their outcome, those cases could send ripples throughout the media, attorneys say, redefining the role of organizations in both covering and correcting misinformation. Fox had yet to respond to Dominion’s suit when this article went to press, but its response to Smartmatic offers a look into its strategy. (Fox News declined to make staffers available for interviews for this story.)

The network argues in the Smartmatic case that President Trump’s election challenges were “undeniably newsworthy” and “matters of public concern”—categories of speech which the law affords some greater protection. “If the First Amendment means anything, it means that Fox cannot be held liable for fairly reporting and commenting on competing allegations in a hotly contested and actively litigated election,” Fox said in a statement. Fox also points to the “factchecking segments” it aired, as well as instances where its own onair staff said that no evidence of wide spread fraud had emerged.

The defense Fox appears to be employing, says Freeman, is known as neutral reportage—the idea that news outlets are allowed to report on and restate important claims made by responsible people. Freeman is one of many advocates who argue that the media should have this right. Neutral reportage is a privilege recognized in few courts, however, and in New York, where Fox is based (and being sued by Smartmatic), the courts have rejected it. And even if a court was receptive, attorneys say Fox might still stumble over the neutrality part; after all, a jury will have to weigh the totality of its coverage, and whether it endorsed its guests’ points. Examples of such perceived endorsement pepper the complaints from Dominion and Smartmatic. In November, for example, Dobbs ended a discussion with Powell about Dominion saying he was “glad” she was working “to straighten out all of this. It is a foul mess, and it is far more sinister than any of us could have imagined.” (Fox dropped Dobbs’s show in February— the day after Smartmatic served its lawsuit—but the network says that the cancellation was unrelated to the defamation cases.)

If Fox were to lose, Dominion and some mainstream commentators will likely hail the win as a triumph of business against misinformation, a line drawn in the sand between facts and alternative facts—and a possible template for future lawsuits. That may be a becarefulwhatyouwish for scenario, says Yale’s Baron. The benefits of reining in actually fake news, if you will, could have a chilling effect on the freedom of the press and on some speech in general. “The hope is that it will only chill those who are likely to lose libel suits,” she says. “I think the country may get an opportunity to learn a lot about the limits, for good or for ill, of libel law in the context of this litigation.”

Beyond the First Amendment, there are other spheres for holding accountable those responsible for the Big Lie. Powell and Giuliani, along with several other attorneys who filed election challenges, are facing complaints from government officials seeking to disbar them from the legal profession entirely. And some law makers who have spread and acted on claims like Powell’s and Giuliani’s are being punished by some donors: Multiple companies have discontinued their donations to the campaigns of lawmakers who declined to certify the validity of the 2020 election.

There’s also the question of whether Dominion’s lawsuits will progress far enough, fast enough, to make a difference. Ironically enough, the toxic information climate exemplified by the Dominion narrative may make it harder to get to the truth. Once it goes to trial, it may be a challenge to empanel enough jurors whose views have not been tainted by the pervasive allegations. Any definitive verdict is likely three to four years down the road, which means there could be another presidential election before a ruling can vindicate the voting machine companies. Should Dominion prevail, its less clear whether it will even make a difference in the minds of the millions for whom the conspiracy theories are gospel.

For Poulos, the issues around integrity and democracy outweigh those concerns. He says Dominion, which is paying the lawyer bills out of its own coffers, has enough runway to pursue the litigation for years and does not plan to settle. “We are not initiating claims to reach a settlement agreement where the truth can’t come out,” he says. “That’s just not of interest to us.” In the mean time, Poulos and his colleagues have been embracing a different mission: explaining to American voters how their elections work. As long as most jurisdictions are using paper ballots—which electoral experts expect even the few holdouts will eventually adopt—there’s a simple path to peace of mind. Nicole Nollette, the Dominion executive, has made it a priority to clear up misinformation. “You don’t need to take our word for it,” she constantly explains. Not when the proof is right there: “You can re count the paper ballots by hand; you can recount them by a machine,” she says. In the future, more states just might—which could be a more effective way to quell conspiracy theories before they catch fire.