论起说废话,埃克森美孚的首席执行官伍德伦其实比不上美国职业篮球联赛的传奇人物迈克尔•乔丹,还有曾经入选达拉斯牛仔队全明星阵容的迪昂•“巅峰时刻”•桑德斯。

但在公开场合,这位沉默寡言的石油巨头高管声音确实比较单调,

轻微拖长的得州口音听起来略带绵软,用词相当考究,让人能够感觉到事先精心准备的温文尔雅。4月下旬,伍德伦宣布埃克森美孚一季度财报,还是一如既往的风格。然而除了典型大企业套话,他的言辞还透露出明显的胜利意味,甚至有一种挑战的感觉。伍德伦在与华尔街分析师的网络直播电话中指出,过去一年公司经历了种种动荡,先是新冠疫情引发一波又一波封锁,还有原油消费量暴跌,然而能源巨头对世界的看法并未改变。他还表示,2021年前三个月,埃克森美孚的利润为27亿美元,主要因为石油天然气价格反弹,也证明公司战略是正确的。

“我们都知道经济会复苏,人口和生活水平将继续增长,最终推动对石油产品的需求,行业也会复苏。”伍德伦说。他还指出,过去几年公司在重组和再投资方面的努力取得了成效。“现在公司实力更强,前景也更好。”

言下之意是:对公司不满,忍着吧。

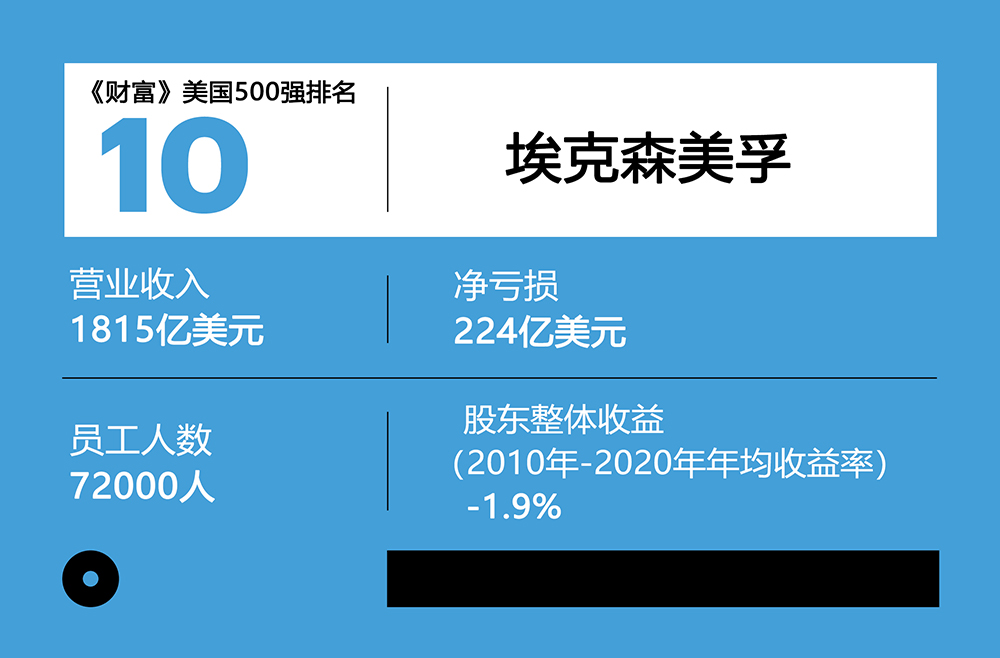

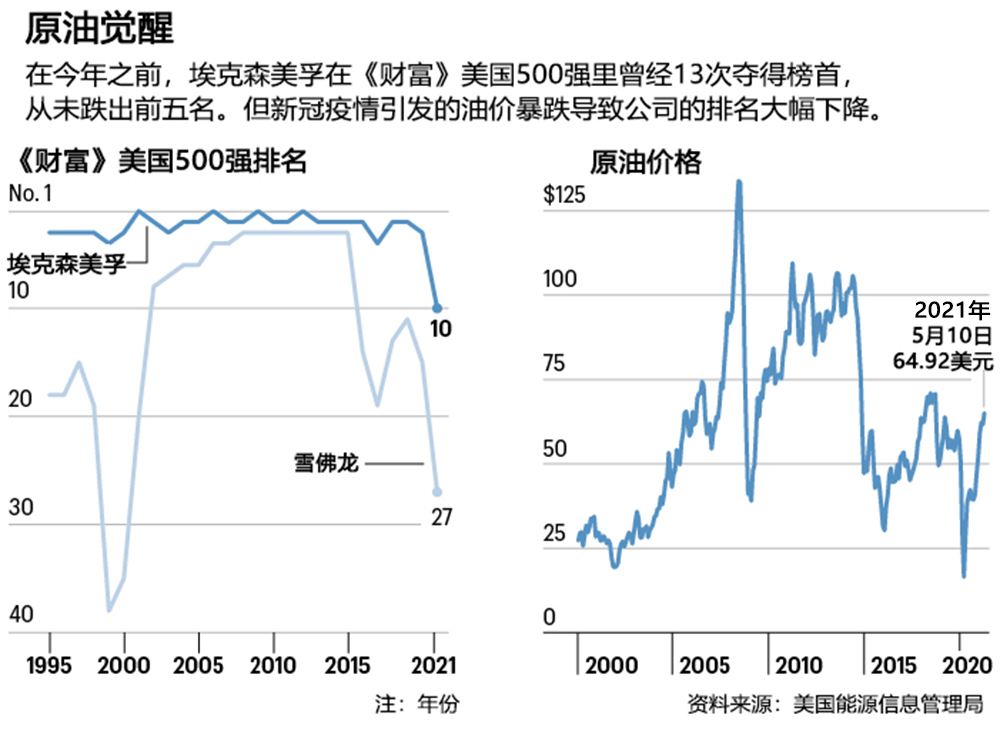

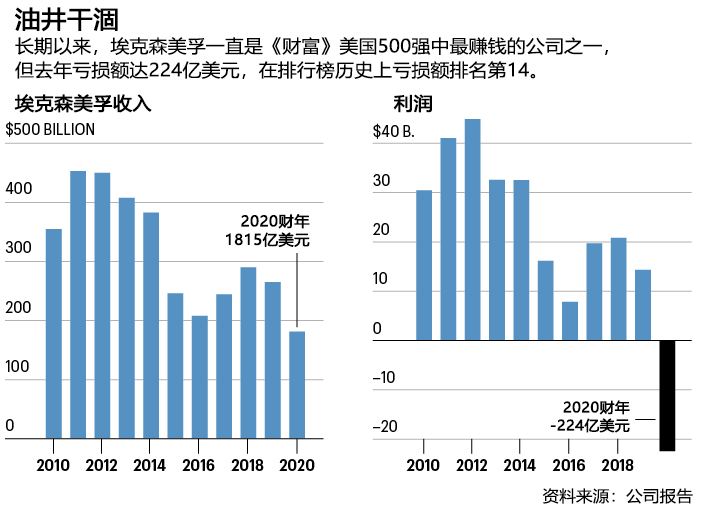

不管对伍德伦还是公司来说,本季度亮眼的业绩都是一场迫切需要的胜利。在过去一年里,曾经强大的埃克森美孚遭受了一系列羞辱。油价暴跌拖累埃克森美孚在2020年的收入比前一年下降了约830亿美元,今年的《财富》美国500强中排名从第3位跌至第10位,也是有史以来最低排名。

更糟糕的是,在20多年没有出现亏损的情况下,2020年亏损创下了224亿美元纪录,也变成《财富》美国500强里亏损最严重的公司。

去年8月,连续92年入选道琼斯工业平均指数30强的埃克森美孚被软件巨头赛富时取代。雪上加霜的是,埃克森美孚的长期竞争对手雪佛龙(今年《财富》美国500强排名第27位,下跌12位)成功保住了在道琼斯指数里的位置。

这一对比肯定让埃克森美孚如芒在背。

到2021年4月,短短一年多时间内穆迪和标准普尔全球都第二次下调埃克森美孚的债务评级。造成这种情况的具体原因是什么?应对气候变化的压力加大,加上埃克森美孚债务水平达到历史上最高,这也是积极投资提升石油天然气产量的副产品。过去五年,该公司的净债务资本比率从16.5%上升到27.8%,仅去年一年的债务总额就增加了近210亿美元。

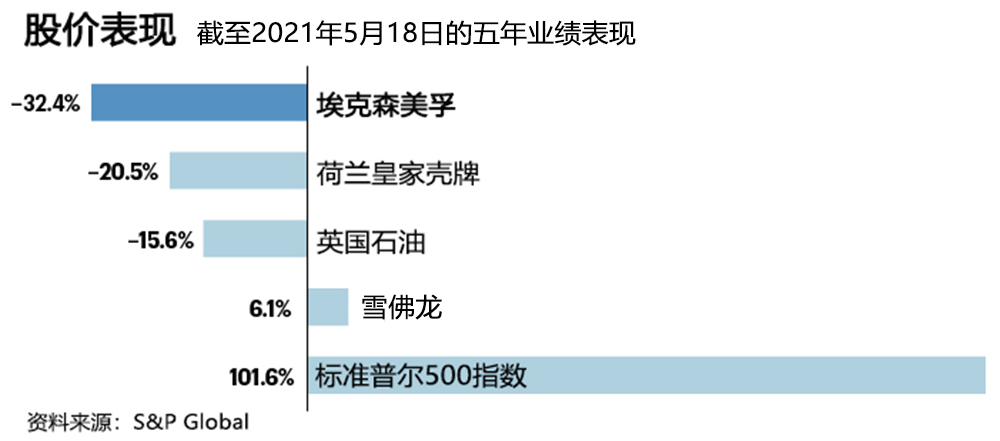

种种不利情况为埃克森美孚的批评者提供了宽敞的场地,简直比石油钻井平台还大。多年来,批评者一直指责公司财富缩水。看看市场表现就知道。

长期以来在投资者看来,埃克森美孚可能是石油巨头当中最自律的一家,公司现金十分充裕,经济低迷时期仍然可以进行投资,经济繁荣时期则擅长变现。不管喜不喜欢,埃克森美孚确实是值得信赖的石油股。

但在过去五年里,公司的股价下跌了32%,雪佛龙的股价上涨了6%,标准普尔500指数飙升了102%。同期,埃克森美孚也落后于竞争对手英国石油(下跌16%)和壳牌(下跌21%)。

今年1月,《华尔街日报》曾经报道埃克森美孚和雪佛龙有意就合并初步商讨,公司未来发展方向也引发了更多疑问。(埃克森美孚拒绝对该篇报道置评。)

眼下是能源从化石燃料向可持续能源转型的新时代,然而埃克森美孚仍然认为在未来几十年内,石油天然气依旧是经济发展的中心,这一根深蒂固的世界观问题不小,甚至可能造成巨大风险,也是各种混乱的源头。

英国石油、壳牌和法国的道达尔等同行均已经承诺到2050年实现碳排放净零,还表示将加快对风能和太阳能的投资,埃克森美孚在投资核心油气以外的业务却相当滞后。

在一家新成立名叫Engine No.1的投资公司领导下,激进投资者纷纷意识到埃克森美孚的弱点,以质疑公司在替代能源方面缺乏行动为名发起代理权争夺战。激进投资者希望找四名新董事重新组建董事会,认为新人能够推动埃克森美孚踏上姗姗来迟的发展之路。

对此,伍德伦特别宣布了一系列改革举措,还启动新业务将低碳技术商业化,引发众多持怀疑态度的观察者高度关注,但观察者认为种种举措都是权宜之计,而且会造成分心。

埃克森美孚内部的问题也在酝酿之中。公司计划裁员15%,涉及约1.4万员工,其中也包括承包商,受此影响,公司的士气较为低落。

根据对埃克森美孚现任和前任各级各部门员工的采访,很多人认为伍德伦担任首席执行官的四年里引起了分歧。一些人批评他缺乏前任的狂傲不羁和声势,另一些人则批评他并不是富有远见的变革推动者。

伍德伦坚称,公司的战略并不依赖油价上涨。但他似乎笃定埃克森美孚困难时期的经典策略会成功,即不断前进等待油价回升。从10月底的37美元飙升至5月底的68美元,原油价格越高,策略成功的几率就越大。

如今公司面临的变革压力比135年历史上任何时候都要紧迫,更大的问题是:公司是否真正希望变革?

*****

伍德伦听起来轻松而自信。

4月初与《财富》杂志的电话采访时,他正在反思过去一年的动荡。他说,尽管可能会很痛苦,但对公司来说,2020年是“关键的一年”,“不仅因为疫情、经济以及对产品的需求,也因为几项因素结合在一起。”他解释说,自己和领导团队刚在2019年秋季制定了重组计划。新冠疫情的冲击推动全公司更快的行动。“疫情确实加快了行动节奏,也让全公司深刻了解了紧迫性。”

2017年1月1日,伍德伦接替雷克斯•蒂勒森担任董事长兼首席执行官时,埃克森美孚似乎并不需要重大改革。事实上,伍德伦执掌的第一个全年,公司利润高达197亿美元,“平均资本回报率”达9%,比之前一年增长一倍以上,这也是公司向来最钟爱的指标。

但蒂勒森离任前往特朗普政府担任国务卿之前几年里,公司债务急剧上升。很快公司内外都发现,蒂勒森给伍德伦留下了一堆烂摊子。

蒂勒森的失误之一是,2010年在页岩气热潮如火如荼之时收购了得克萨斯州的页岩公司XTO,还出了350亿美元的高价。

为了刺激增长,伍德伦采用了埃克森美孚典型的做法,押宝大型项目,一旦油价上涨就会获得丰厚利润。根据他的重组计划,公司2025年前每年运营支出将增加300亿至350亿美元,重点放在“五大”特别有希望的大型油气项目上,从得克萨斯的二叠纪盆地到圭亚那再到莫桑比克,与此同时抛售其他资产。

伍德伦预计,到2025年日产量将跃升至相当于200万桶石油水平,收益可以翻一番。

然后疫情打乱了伍德伦的算盘。国际能源署的数据显示,2020年全球石油需求较2019年下降了880万桶/天,价格降幅更大。(2020年4月交易中,每桶石油的成本甚至短时间降到每桶负38美元。)

伍德伦立即削减了30%的资本支出,并表示到2023年成本将减少60亿美元。然而,埃克森美孚的股息成本并未受影响。

英国石油和壳牌在经历巨额亏损后,2020年都减少了股息,埃克森美孚却不一样,即便举债也要保持稳定派息。

据现任和前任员工透露,带领公司应对种种挑战的过程中,伍德伦也在努力争取埃克森美孚员工认同。他在首席执行官职位上两位前辈都很难效仿。

李•雷蒙德风格出了名的强硬,1999年曾经主导从J•D•洛克菲勒旗下的标准石油公司分拆出的埃克森和美孚合并,而且一直领导到2005年。

蒂勒森也是耀眼而有魅力的领袖。相比之下,伍德伦更为保守。他在得州农工大学攻读工程专业后,职业生涯全在埃克森美孚,是公司保守、命令控制型文化的产物,晋升时被认为言辞犀利且直率。但他的领导风格并未激励多少员工,还让很多人感觉不舒服。

举个例子,现任和前任员工指出,伍德伦在担任首席执行官大约一年后曾经召开全员会议,结果却非常糟。

伍德伦即席发表讲话,为竞争激烈且极不受欢迎的员工排名制度辩护称,此举能够确保精英领导。

一位当时在场的员工表示,他还回忆起有一次解雇一名哭泣的女员工,一年后,那名女员工回来感谢他给自己机会寻找新岗位。该次会议给人留下的印象是伍德伦听不出别人的言外之意,而且很傲慢。

一位前高级经理说,公司内部认为该起事件堪称“车祸”,而且消息在公司里迅速传开。当回答有关全员会议的问题时,埃克森美孚的发言人提供了一份声明称:“伍德伦继续与员工定期接触交谈,参与全员会议,听取员工反馈,领导公司时将加以考虑。”

*****

ENGINE NO. 1迅速向全世界表明了来意。

12月7日,新成立的激进投资公司在公开市场部署了2.5亿美元的资金,以埃克森美孚为目标发起了第一次行动。该基金在一份声明中宣布了开场白:“在石油天然气历史上,没有哪家公司的影响力可以超过埃克森美孚。”

不过“很明显,整个行业和世界都在发生变化,埃克森美孚也必须改变。”

该公司的总部位于旧金山,由对冲基金资深人士克里斯•詹姆斯创立,他是Partner fund Management和Andor Capital Management的联合创始人。

在针对埃克森美孚的行动中,这家公司争取到美国最大几家养老基金的支持。还声称,埃克森美孚的董事会成员中没有人深入了解能源行业,所以无法领导绿色转型。

于是ENGINE NO. 1挑选了四位资历合适的候选人加入董事会。其中一位是美国石油天然气公司Andeavor的前首席执行官;还有一位曾经领导一家芬兰的能源公司向可再生燃料转型。

有人可能认为,由于埃克森美孚长期以来在气候变化问题上态度顽固,与Engine No. 1的斗争是迄今为止最艰巨的挑战。

前首席执行官雷蒙德曾经多次质疑气候变化。在蒂勒森的领导下,埃克森美孚公开承认气候变化确实存在。

Union of Concerned Scientists却在一份报告中声称,公司私下继续资助有问题的科研项目,目的是混淆气候变化相关的研究。

埃克森美孚则表示,报告“故意误报”了公司在气候变化问题上的立场,指责公司所属的贸易组织“否认气候变化”也毫无道理。

哥伦比亚大学萨宾气候变化法律中心的创始人迈克尔•杰拉德表示,埃克森美孚的过往记录造成的长期阴影既有声誉方面,也有法律层面。

目前埃克森美孚正在面临地方和州政府20起与气候变化有关的诉讼。杰拉德说,埃克森美孚“无疑”成为美国气候变化相关诉讼最多的被告。到目前为止,还没有诉讼成功的案例。

2019年,埃克森美孚在纽约总检察长提起的诉讼中获胜,该案指称埃克森美孚轻视气候变化风险。

伍德伦本人也表现得要更开放更透明应对气候变化。他经常谈到2015年的《巴黎协议》,在投资者陈述中也用了很长篇幅来阐述,有时甚至长期批评者听着都烦躁。

Union of Concerned Scientists下属气候能源项目的负责任运动的主任凯西•穆尔维称,有一次在埃克森美孚的年会上,开头20分钟伍德伦都在谈环境问题。

“如果你是刚从外太空来地球的外星人,一落地就去开这场会。”穆尔维说,“真会以为这家公司非常重视解决气候变化。”

但批评人士表示,埃克森美孚在气候变化问题上言辞越发友好温柔,实际行动却并非如此。

举个例子,看看公司如何声称减排符合《巴黎协定》。埃克森美孚的目标是到2025年将上游排放削减15%至20%,甲烷排放削减40%至50%,仅涵盖公司自行经营项目的排放。(在10-K报告中,该公司称约13%的油井并未经营。)

而且减排仅涉及埃克森美孚自身的排放量或项目使用的能源,即所谓的经营性排放量或“1级”和“2级”。英国石油和壳牌则已经将3级目标囊括在内,尽可能涵盖与石油天然气相关排放,包括汽车和飞机使用化石燃料动力产生的排放量。

埃克森美孚表示,之所以报告范围限制在1级和2级排放量,是因为受公司直接控制,如何报告也很清楚,公司认为3级排放量数据不太一致,可能引发误导。

伍德伦一直对竞争对手的远大目标不屑一顾。在2020年3月与投资者进行的一次电话会议上,他表示同行提出的目标更像“选美比赛”,还指出将石油天然气资产出售给“效率较低的运营商只会让问题更糟”。

在伍德伦看来,要更“全面”地解决问题。

当回答有关埃克森美孚应对气候变化方法的问题时,一位发言人指出,自2000年以来,公司在低排放技术方面的投资超过100亿美元,他还说:“我们努力应对气候变化的风险,尽力寻找解决方案。”

但一位前员工不无遗憾地表示,埃克森美孚内部的真实态度是,不管消费者喜不喜欢公司,还是需要公司的产品。

“我们根本不打扮猪,也不会给猪抹口红。我们只会说:‘人人都喜欢培根,那就闭嘴吧。’”

当然,即便埃克森美孚的欧洲竞争对手都采取更环保的政策,产生的影响也不够重大。

5月下旬,总部位于巴黎的国际能源署发布了一份意义重大的报告称,为在2050年前将排放量降至净零,从现在起不应该对油气田进行新投资,而各大油气公司均未就此做出承诺。

*****

至于油气巨头应该如何对付气候变化,埃克森美孚的结论完全不同。

2月1日,伍德伦宣布推出一项名叫“低碳解决方案”的新业务,将埃克森美孚一直在开发的技术商业化。首先从碳捕获和储存(CCS)开始,即捕获并阻止燃烧提取化石燃料产生的二氧化碳进入大气层。

伍德伦表示,从2021年到2025年,埃克森美孚将在低碳解决方案上投资30亿美元。

Engine No. 1声称,公司迫于投资者的压力才改变气候变化方面的言论。伍德伦称,只是时机合适而已。

他说,风能和太阳能“虽然很重要”,但并不是“完整的解决方案”,多年来该公司一直努力提升CCS技术。他表示,目标不仅是帮自家公司抵消排放量,还要建立新业务,毕竟各企业纷纷做出净零排放承诺,都要想办法抵消排放量。当然,政治风向也发生了转变。

“我认为,拜登政府的改革以及重视减排都为加快技术推进提供了助力,也为我们开展技术和碳捕获方面工作并转变为全面的业务奠定了基础。”伍德伦说。

但到目前为止,除了已经宣布的内容,新成立的合资公司并未宣布新项目。

专家和分析人士还表示,如果没有新激励措施,首先就是自2009年以来,埃克森美孚一直公开支持的征收碳排放税,目前在美国启动大型CCS项目并不划算。

埃克森美孚并未反对。谈到利用CCS项目盈利时,

“美国还没有推动此类项目的激励架构。”盖伊•鲍威尔表示,他从2018年就开始在埃克森美孚内部领导CCS项目,目前正在协助领导低碳解决方案。“但我们确实看到了潜在的政治意愿,即建立正确的激励机制、监管和法律结构以实现目标。”鲍威尔说,公司正在与决策者接洽,其他项目也在进行中。

尽管埃克森美孚自称在捕获CCS方面全球领先,但批评人士认为,这项技术也有难题:该公司的方法侧重于“提高石油采收率”,即向地下注入二氧化碳以排出更多石油,并不仅是为了减少碳排放进行长期封存。

鲍威尔指出,美国目前的大部分CCS工作都是为了石油开采,石油天然气行业已经使用数十年的技术与长期封存相比需要“不同的技术和操作”。但他认为,最终结果都一样。

“只是过程不同,最终结果都是将二氧化碳安全留在地面上。”鲍威尔说。

一些行业分析师公开质疑新业务的价值。“这不仅是概念,比起资本转移更是发展方向调整。”跟踪埃克森美孚的花旗董事总经理阿拉斯泰尔•赛姆表示。

“我认为此举主要为了游说。”

*****

在Engine No. 1与埃克森美孚代理权之争公开以来的几个月里,基金与能源巨头摊牌的赌注逐渐提高。

自年初以来,埃克森美孚董事会已经增加三名新成员,其中包括马来西亚国家能源公司前首席执行官,也是激进投资者杰弗里•乌本,他是总部位于旧金山的对冲基金ValueAct Capital的创始人。

但Engine No. 1支持者越来越多。美国三大养老基金均已经公开支持,包括加州雇员退休基金、加州教师退休基金和纽约州共同退休基金,还有管理资产超过1万亿美元的英国资产管理公司法通。包括机构股东服务公司和Glass Lewis在内四家主要代理咨询公司支持Engine No. 1更换部分董事会成员。

Glass Lewis在报告中称:“虽然埃克森美孚声称战略有所发展,在石油巨头中也保住了历来的领导地位,但我们认为,该公司竞争地位和财务回报均受到影响,其宣称能够彻底解决业绩下滑的策略基本上作用不大。”

在投票的前一天晚上,激进投资者一方再下一城,路透社报道称全球最大的资产管理公司贝莱德已经投票支持Engine No. 1四位候选人中的三位。

最终投票成功与否将取决于其他机构巨头先锋和道富银行支持哪一方。

伍德伦陈述观点时一直咄咄逼人。在一季度财报电话会议上回应分析师的问题时,他坚定支持埃克森美孚现任董事会的专业性,还表示公司与股东打交道的方式已经改变。

“我们收到反馈就会回应。”他说。

Engine No. 1则表示,埃克森美孚已经错失就如何应对长期气候变化展开认真辩论的机会。

在发起代理权争斗之前,“埃克森美孚骄傲的回应空无一物。”Engine No. 1的积极行动负责人查理•彭纳说,他也领导了埃克森美孚代理权之争。“发现可能保不住董事会席位后,他们没有积极辩论,而是穿上另一队制服然后全力逃避。”

他们的制服就是能源转型。

即便埃克森美孚没有撤换董事会成员,本次动荡会不会迫使埃克森美孚真正变革?业内观察人士对此意见不一。

有人说,本次事件是在警告,世界不断变化,埃克森美孚也不能独善其身。

其他人说,石油巨头很可能会恢复正常经营,尤其是如果石油天然气价格继续上涨,埃克森美孚的股价也会走高。截至5月下旬,自年初以来的埃克森美孚股价已经上涨41%。

当问起伍德伦埃克森美孚员工对公司未来有何疑问时,他相当谨慎。

“内部的问题与外部的问题比较一致。”他说,“由于社会需求也渴望低碳密集型能源,如何随着时间推移实现这种需求?对公司有何影响?如何稳妥执掌公司,顺利渡过转型?”

他的语调一如既往地沉稳:“我们的工作是满足社会不断变化的需求。历来都是这么做的。”

别催他,等等看。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

论起说废话,埃克森美孚的首席执行官伍德伦其实比不上美国职业篮球联赛的传奇人物迈克尔•乔丹,还有曾经入选达拉斯牛仔队全明星阵容的迪昂•“巅峰时刻”•桑德斯。

至少在公开场合,这位沉默寡言的石油巨头高管声音有些单调,轻微拖长的得州口音听起来略带绵软,用词相当考究,让人能够感觉到事先精心准备的温文尔雅。4月下旬,伍德伦宣布埃克森美孚一季度财报,还是一如既往的风格。然而除了典型大企业套话,他的言辞还透露出明显的胜利意味,甚至有一种挑战的感觉。

伍德伦在与华尔街分析师的网络直播电话中指出,过去一年公司经历了种种动荡,先是新冠疫情引发一波又一波封锁,还有原油消费量暴跌,然而能源巨头对世界的看法并未改变。他还表示,2021年前三个月,埃克森美孚的利润为27亿美元,主要因为石油天然气价格反弹,也证明公司战略是正确的。

“我们都知道经济会复苏,人口和生活水平将继续增长,最终推动对石油产品的需求,行业也会复苏。”伍德伦说。他还指出,过去几年公司在重组和再投资方面的努力取得了成效。“现在公司实力更强,前景也更好。”

言下之意是:对公司不满,忍着吧。

不管对伍德伦还是公司来说,本季度亮眼的业绩都是一场迫切需要的胜利。在过去一年里,曾经强大的埃克森美孚遭受了一系列羞辱。油价暴跌拖累埃克森美孚在2020年的收入比前一年下降了约830亿美元,今年的《财富》美国500强中排名从第3位跌至第10位,也是有史以来最低排名。

更糟糕的是,在20多年没有出现亏损的情况下,2020年亏损创下了224亿美元纪录,也变成《财富》美国500强里亏损最严重的公司。

去年8月,连续92年入选道琼斯工业平均指数30强的埃克森美孚被软件巨头赛富时取代。雪上加霜的是,埃克森美孚的长期竞争对手雪佛龙(今年《财富》美国500强排名第27位,下跌12位)成功保住了在道琼斯指数里的位置。

这一对比肯定让埃克森美孚如芒在背。

到2021年4月,短短一年多时间内穆迪和标准普尔全球都第二次下调埃克森美孚的债务评级。造成这种情况的具体原因是什么?应对气候变化的压力加大,加上埃克森美孚债务水平达到历史上最高,这也是积极投资提升石油天然气产量的副产品。过去五年,该公司的净债务资本比率从16.5%上升到27.8%,仅去年一年的债务总额就增加了近210亿美元。

种种不利情况为埃克森美孚的批评者提供了宽敞的场地,简直比石油钻井平台还大。多年来,批评者一直指责公司财富缩水。看看市场表现就知道。

长期以来在投资者看来,埃克森美孚可能是石油巨头当中最自律的一家,公司现金十分充裕,经济低迷时期仍然可以进行投资,经济繁荣时期则擅长变现。不管喜不喜欢,埃克森美孚确实是值得信赖的石油股。

但在过去五年里,公司的股价下跌了32%,雪佛龙的股价上涨了6%,标准普尔500指数飙升了102%。同期,埃克森美孚也落后于竞争对手英国石油(下跌16%)和壳牌(下跌21%)。

今年1月,《华尔街日报》曾经报道埃克森美孚和雪佛龙有意就合并初步商讨,公司未来发展方向也引发了更多疑问。(埃克森美孚拒绝对该篇报道置评。)

眼下是能源从化石燃料向可持续能源转型的新时代,然而埃克森美孚仍然认为在未来几十年内,石油天然气依旧是经济发展的中心,这一根深蒂固的世界观问题不小,甚至可能造成巨大风险,也是各种混乱的源头。

英国石油、壳牌和法国的道达尔等同行均已经承诺到2050年实现碳排放净零,还表示将加快对风能和太阳能的投资,埃克森美孚在投资核心油气以外的业务却相当滞后。

在一家新成立名叫Engine No.1的投资公司领导下,激进投资者纷纷意识到埃克森美孚的弱点,以质疑公司在替代能源方面缺乏行动为名发起代理权争夺战。激进投资者希望找四名新董事重新组建董事会,认为新人能够推动埃克森美孚踏上姗姗来迟的发展之路。

对此,伍德伦特别宣布了一系列改革举措,还启动新业务将低碳技术商业化,引发众多持怀疑态度的观察者高度关注,但观察者认为种种举措都是权宜之计,而且会造成分心。

埃克森美孚内部的问题也在酝酿之中。公司计划裁员15%,涉及约1.4万员工,其中也包括承包商,受此影响,公司的士气较为低落。

根据对埃克森美孚现任和前任各级各部门员工的采访,很多人认为伍德伦担任首席执行官的四年里引起了分歧。一些人批评他缺乏前任的狂傲不羁和声势,另一些人则批评他并不是富有远见的变革推动者。

伍德伦坚称,公司的战略并不依赖油价上涨。但他似乎笃定埃克森美孚困难时期的经典策略会成功,即不断前进等待油价回升。从10月底的37美元飙升至5月底的68美元,原油价格越高,策略成功的几率就越大。

如今公司面临的变革压力比135年历史上任何时候都要紧迫,更大的问题是:公司是否真正希望变革?

*****

伍德伦听起来轻松而自信。

4月初与《财富》杂志的电话采访时,他正在反思过去一年的动荡。他说,尽管可能会很痛苦,但对公司来说,2020年是“关键的一年”,“不仅因为疫情、经济以及对产品的需求,也因为几项因素结合在一起。”他解释说,自己和领导团队刚在2019年秋季制定了重组计划。新冠疫情的冲击推动全公司更快的行动。“疫情确实加快了行动节奏,也让全公司深刻了解了紧迫性。”

2017年1月1日,伍德伦接替雷克斯•蒂勒森担任董事长兼首席执行官时,埃克森美孚似乎并不需要重大改革。事实上,伍德伦执掌的第一个全年,公司利润高达197亿美元,“平均资本回报率”达9%,比之前一年增长一倍以上,这也是公司向来最钟爱的指标。

但蒂勒森离任前往特朗普政府担任国务卿之前几年里,公司债务急剧上升。很快公司内外都发现,蒂勒森给伍德伦留下了一堆烂摊子。

蒂勒森的失误之一是,2010年在页岩气热潮如火如荼之时收购了得克萨斯州的页岩公司XTO,还出了350亿美元的高价。

为了刺激增长,伍德伦采用了埃克森美孚典型的做法,押宝大型项目,一旦油价上涨就会获得丰厚利润。根据他的重组计划,公司2025年前每年运营支出将增加300亿至350亿美元,重点放在“五大”特别有希望的大型油气项目上,从得克萨斯的二叠纪盆地到圭亚那再到莫桑比克,与此同时抛售其他资产。

伍德伦预计,到2025年日产量将跃升至相当于200万桶石油水平,收益可以翻一番。

然后疫情打乱了伍德伦的算盘。国际能源署的数据显示,2020年全球石油需求较2019年下降了880万桶/天,价格降幅更大。(2020年4月交易中,每桶石油的成本甚至短时间降到每桶负38美元。)

伍德伦立即削减了30%的资本支出,并表示到2023年成本将减少60亿美元。然而,埃克森美孚的股息成本并未受影响。

英国石油和壳牌在经历巨额亏损后,2020年都减少了股息,埃克森美孚却不一样,即便举债也要保持稳定派息。

据现任和前任员工透露,带领公司应对种种挑战的过程中,伍德伦也在努力争取埃克森美孚员工认同。他在首席执行官职位上两位前辈都很难效仿。

李•雷蒙德风格出了名的强硬,1999年曾经主导从J•D•洛克菲勒旗下的标准石油公司分拆出的埃克森和美孚合并,而且一直领导到2005年。

蒂勒森也是耀眼而有魅力的领袖。相比之下,伍德伦更为保守。他在得州农工大学攻读工程专业后,职业生涯全在埃克森美孚,是公司保守、命令控制型文化的产物,晋升时被认为言辞犀利且直率。但他的领导风格并未激励多少员工,还让很多人感觉不舒服。

举个例子,现任和前任员工指出,伍德伦在担任首席执行官大约一年后曾经召开全员会议,结果却非常糟。

伍德伦即席发表讲话,为竞争激烈且极不受欢迎的员工排名制度辩护称,此举能够确保精英领导。

一位当时在场的员工表示,他还回忆起有一次解雇一名哭泣的女员工,一年后,那名女员工回来感谢他给自己机会寻找新岗位。该次会议给人留下的印象是伍德伦听不出别人的言外之意,而且很傲慢。

一位前高级经理说,公司内部认为该起事件堪称“车祸”,而且消息在公司里迅速传开。当回答有关全员会议的问题时,埃克森美孚的发言人提供了一份声明称:“伍德伦继续与员工定期接触交谈,参与全员会议,听取员工反馈,领导公司时将加以考虑。”

*****

ENGINE NO. 1迅速向全世界表明了来意。

12月7日,新成立的激进投资公司在公开市场部署了2.5亿美元的资金,以埃克森美孚为目标发起了第一次行动。该基金在一份声明中宣布了开场白:“在石油天然气历史上,没有哪家公司的影响力可以超过埃克森美孚。”

不过“很明显,整个行业和世界都在发生变化,埃克森美孚也必须改变。”

该公司的总部位于旧金山,由对冲基金资深人士克里斯•詹姆斯创立,他是Partner fund Management和Andor Capital Management的联合创始人。

在针对埃克森美孚的行动中,这家公司争取到美国最大几家养老基金的支持。还声称,埃克森美孚的董事会成员中没有人深入了解能源行业,所以无法领导绿色转型。

于是ENGINE NO. 1挑选了四位资历合适的候选人加入董事会。其中一位是美国石油天然气公司Andeavor的前首席执行官;还有一位曾经领导一家芬兰的能源公司向可再生燃料转型。

有人可能认为,由于埃克森美孚长期以来在气候变化问题上态度顽固,与Engine No. 1的斗争是迄今为止最艰巨的挑战。

前首席执行官雷蒙德曾经多次质疑气候变化。在蒂勒森的领导下,埃克森美孚公开承认气候变化确实存在。

Union of Concerned Scientists却在一份报告中声称,公司私下继续资助有问题的科研项目,目的是混淆气候变化相关的研究。

埃克森美孚则表示,报告“故意误报”了公司在气候变化问题上的立场,指责公司所属的贸易组织“否认气候变化”也毫无道理。

哥伦比亚大学萨宾气候变化法律中心的创始人迈克尔•杰拉德表示,埃克森美孚的过往记录造成的长期阴影既有声誉方面,也有法律层面。

目前埃克森美孚正在面临地方和州政府20起与气候变化有关的诉讼。杰拉德说,埃克森美孚“无疑”成为美国气候变化相关诉讼最多的被告。到目前为止,还没有诉讼成功的案例。

2019年,埃克森美孚在纽约总检察长提起的诉讼中获胜,该案指称埃克森美孚轻视气候变化风险。

伍德伦本人也表现得要更开放更透明应对气候变化。他经常谈到2015年的《巴黎协议》,在投资者陈述中也用了很长篇幅来阐述,有时甚至长期批评者听着都烦躁。

Union of Concerned Scientists下属气候能源项目的负责任运动的主任凯西•穆尔维称,有一次在埃克森美孚的年会上,开头20分钟伍德伦都在谈环境问题。

“如果你是刚从外太空来地球的外星人,一落地就去开这场会。”穆尔维说,“真会以为这家公司非常重视解决气候变化。”

但批评人士表示,埃克森美孚在气候变化问题上言辞越发友好温柔,实际行动却并非如此。

举个例子,看看公司如何声称减排符合《巴黎协定》。埃克森美孚的目标是到2025年将上游排放削减15%至20%,甲烷排放削减40%至50%,仅涵盖公司自行经营项目的排放。(在10-K报告中,该公司称约13%的油井并未经营。)

而且减排仅涉及埃克森美孚自身的排放量或项目使用的能源,即所谓的经营性排放量或“1级”和“2级”。英国石油和壳牌则已经将3级目标囊括在内,尽可能涵盖与石油天然气相关排放,包括汽车和飞机使用化石燃料动力产生的排放量。

埃克森美孚表示,之所以报告范围限制在1级和2级排放量,是因为受公司直接控制,如何报告也很清楚,公司认为3级排放量数据不太一致,可能引发误导。

伍德伦一直对竞争对手的远大目标不屑一顾。在2020年3月与投资者进行的一次电话会议上,他表示同行提出的目标更像“选美比赛”,还指出将石油天然气资产出售给“效率较低的运营商只会让问题更糟”。

在伍德伦看来,要更“全面”地解决问题。

当回答有关埃克森美孚应对气候变化方法的问题时,一位发言人指出,自2000年以来,公司在低排放技术方面的投资超过100亿美元,他还说:“我们努力应对气候变化的风险,尽力寻找解决方案。”

但一位前员工不无遗憾地表示,埃克森美孚内部的真实态度是,不管消费者喜不喜欢公司,还是需要公司的产品。

“我们根本不打扮猪,也不会给猪抹口红。我们只会说:‘人人都喜欢培根,那就闭嘴吧。’”

当然,即便埃克森美孚的欧洲竞争对手都采取更环保的政策,产生的影响也不够重大。

5月下旬,总部位于巴黎的国际能源署发布了一份意义重大的报告称,为在2050年前将排放量降至净零,从现在起不应该对油气田进行新投资,而各大油气公司均未就此做出承诺。

*****

至于油气巨头应该如何对付气候变化,埃克森美孚的结论完全不同。

2月1日,伍德伦宣布推出一项名叫“低碳解决方案”的新业务,将埃克森美孚一直在开发的技术商业化。首先从碳捕获和储存开始,即捕获并阻止燃烧提取化石燃料产生的二氧化碳进入大气层。

伍德伦表示,从2021年到2025年,埃克森美孚将在低碳解决方案上投资30亿美元。

Engine No. 1声称,公司迫于投资者的压力才改变气候变化方面的言论。伍德伦称,只是时机合适而已。

他说,风能和太阳能“虽然很重要”,但并不是“完整的解决方案”,多年来该公司一直努力提升CCS技术。他表示,目标不仅是帮自家公司抵消排放量,还要建立新业务,毕竟各企业纷纷做出净零排放承诺,都要想办法抵消排放量。当然,政治风向也发生了转变。

“我认为,拜登政府的改革以及重视减排都为加快技术推进提供了助力,也为我们开展技术和碳捕获方面工作并转变为全面的业务奠定了基础。”伍德伦说。

但到目前为止,除了已经宣布的内容,新成立的合资公司并未宣布新项目。

专家和分析人士还表示,如果没有新激励措施,首先就是自2009年以来,埃克森美孚一直公开支持的征收碳排放税,目前在美国启动大型CCS项目并不划算。

埃克森美孚并未反对。谈到利用CCS项目盈利时,

“美国还没有推动此类项目的激励架构。”盖伊•鲍威尔表示,他从2018年就开始在埃克森美孚内部领导CCS项目,目前正在协助领导低碳解决方案。“但我们确实看到了潜在的政治意愿,即建立正确的激励机制、监管和法律结构以实现目标。”鲍威尔说,公司正在与决策者接洽,其他项目也在进行中。

尽管埃克森美孚自称在捕获CCS方面全球领先,但批评人士认为,这项技术也有难题:该公司的方法侧重于“提高石油采收率”,即向地下注入二氧化碳以排出更多石油,并不仅是为了减少碳排放进行长期封存。

鲍威尔指出,美国目前的大部分CCS工作都是为了石油开采,石油天然气行业已经使用数十年的技术与长期封存相比需要“不同的技术和操作”。但他认为,最终结果都一样。

“只是过程不同,最终结果都是将二氧化碳安全留在地面上。”鲍威尔说。

一些行业分析师公开质疑新业务的价值。“这不仅是概念,比起资本转移更是发展方向调整。”跟踪埃克森美孚的花旗董事总经理阿拉斯泰尔•赛姆表示。

“我认为此举主要为了游说。”

*****

在Engine No. 1与埃克森美孚代理权之争公开以来的几个月里,基金与能源巨头摊牌的赌注逐渐提高。

自年初以来,埃克森美孚董事会已经增加三名新成员,其中包括马来西亚国家能源公司前首席执行官,也是激进投资者杰弗里•乌本,他是总部位于旧金山的对冲基金ValueAct Capital的创始人。

但Engine No. 1支持者越来越多。美国三大养老基金均已经公开支持,包括加州雇员退休基金、加州教师退休基金和纽约州共同退休基金,还有管理资产超过1万亿美元的英国资产管理公司法通。包括机构股东服务公司和Glass Lewis在内四家主要代理咨询公司支持Engine No. 1更换部分董事会成员。

Glass Lewis在报告中称:“虽然埃克森美孚声称战略有所发展,在石油巨头中也保住了历来的领导地位,但我们认为,该公司竞争地位和财务回报均受到影响,其宣称能够彻底解决业绩下滑的策略基本上作用不大。”

在投票的前一天晚上,激进投资者一方再下一城,路透社报道称全球最大的资产管理公司贝莱德已经投票支持Engine No. 1四位候选人中的三位。

最终投票成功与否将取决于其他机构巨头先锋和道富银行支持哪一方。

伍德伦陈述观点时一直咄咄逼人。在一季度财报电话会议上回应分析师的问题时,他坚定支持埃克森美孚现任董事会的专业性,还表示公司与股东打交道的方式已经改变。

“我们收到反馈就会回应。”他说。

Engine No. 1则表示,埃克森美孚已经错失就如何应对长期气候变化展开认真辩论的机会。

在发起代理权争斗之前,“埃克森美孚骄傲的回应空无一物。”Engine No. 1的积极行动负责人查理•彭纳说,他也领导了埃克森美孚代理权之争。“发现可能保不住董事会席位后,他们没有积极辩论,而是穿上另一队制服然后全力逃避。”

他们的制服就是能源转型。

即便埃克森美孚没有撤换董事会成员,本次动荡会不会迫使埃克森美孚真正变革?业内观察人士对此意见不一。

有人说,本次事件是在警告,世界不断变化,埃克森美孚也不能独善其身。

其他人说,石油巨头很可能会恢复正常经营,尤其是如果石油天然气价格继续上涨,埃克森美孚的股价也会走高。截至5月下旬,自年初以来的埃克森美孚股价已经上涨41%。

当问起伍德伦埃克森美孚员工对公司未来有何疑问时,他相当谨慎。

“内部的问题与外部的问题比较一致。”他说,“由于社会需求也渴望低碳密集型能源,如何随着时间推移实现这种需求?对公司有何影响?如何稳妥执掌公司,顺利渡过转型?”

他的语调一如既往地沉稳:“我们的工作是满足社会不断变化的需求。历来都是这么做的。”

别催他,等等看。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

WHEN IT COMES to trash-talking, Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods isn’t exactly on par with, say, NBA legend Michael Jordan or former Dallas Cowboys All-Pro Deion “Prime Time” Sanders. At least in public, the buttoned-up Big Oil executive typically speaks in a near-monotone drone, softened slightly by his light Texas drawl, and chooses his words so carefully as to suggest a curated blandness. That understated presentation style was on display once again in late April when Woods announced the oil and gas giant’s first-quarter earnings. And yet, behind the Exxon-speak, there was an unmistakable note of triumph, perhaps even a hint of defiance.

On the webcast call with Wall Street analysts, Woods pointed out that a year of tumult—a pandemic, the resulting waves of lockdowns, and tumbling crude consumption—had done nothing to change the energy giant’s perspective on the world. And he offered that Exxon’s $2. 7 billion profit in the first three months of 2021, helped by rebounding oil and gas prices, was proof that the company’s strategy was right. “We knew economies would recover, populations and living standards would continue to grow—ultimately driving demand for our products and industry recovery.” Woods said. Meanwhile, he noted, the efforts by the company over the past few years to restructure and reinvest had paid off: “We are a stronger company with an improving outlook.”

Translation: Take that, haters.

The strong quarter was a much-needed win both for Woods and his company after a year in which once-mighty Exxon has suffered a series of painful indignities. Collapsing oil prices caused Exxon’s revenues to sink by some $83 billion in 2020 compared with the year before and sent the energy titan tumbling in this year’s Fortune 500, from No. 3 down to No. 10—Exxon’s lowest-ever spot in the rankings. Worse still, after more than two decades without a negative quarter, the company took a record $22. 4 billion loss in 2020. That made it the biggest money-loser in the Fortune 500 by a wide margin. In August, Exxon was removed from the Dow Jones industrial average after 92 consecutive years as a member of the 30-company index, and replaced by software giant Salesforce. Adding further insult to injury, Exxon’s longtime rival Chevron (No. 27 on this year’s Fortune 500, down 12 spots) kept its place in the Dow. That had to sting.

By April 2021, both Moody’s and S&P Global had downgraded Exxon’s debt for a second time in just over a year. The reason? Increased pressure to address climate change combined with the highest debt levels in Exxon’s history—a by-product of aggressive investments intended to boost the company’s oil and gas production. The company’s net debt-to-capital ratio has risen from 16. 5% to 27. 8% in the past five years, and its total debt load increased by nearly $21 billion last year alone.

The setbacks have given an oil-rig-size opening to Exxon’s critics, who argue that the company’s fortunes have been on the wane for years. Look no further than its market performance. Exxon has long enjoyed a reputation among investors as perhaps Big Oil’s most disciplined operator—so cash-rich that it could invest during downturns and capitalize in booms. Love it or hate it, Exxon was the oil stock you could count on. But over the past five years, its shares have fallen 32% while Chevron’s have risen 6% and the S&P 500 has soared 102%. Exxon also lags rivals BP (down 16%) and Shell(down 21%) over the same period.

The news, reported by the Wall Street Journal in January, that Exxon and Chevron had held preliminary merger discussions raised even more questions about the future direction of the company. (Exxon declined to comment on the report.)

Underpinning all the tumult is a suspicion that Exxon's long-established world view—of oil and gas being at the center of economic growth for decades to come—has become financially shaky, even deeply risky, in a new age of energy transition away from fossil fuels and toward more sustainable sources. While peers like BP, Shell, and France's Total have made commitments to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and have said they will accelerate investments in wind and solar, Exxon has dragged its feet on investing in anything outside its core oil and gas business.

Sensing weakness, activist investors—led by a newly created investment firm called Engine No. 1—have launched a proxy battle challenging Exxon over its lack of action on an alternative energy strategy. They are seeking to remake the company's board with a slate of four new directors who, they argue, can help guide Exxon's long-overdue evolution. In response, Woods has announced a series of overhaul initiatives-in particular, the launch of a new business to commercialize Exxon's low-carbon technology-that have been received with raised eyebrows by a wide range of skeptical observers, who view the moves as half measures and distractions. As Fortune went to press, the two sides were gearing up for a showdown at Exxon's annual meeting in late May.

Problems are brewing for Woods inside Exxon, too. Morale has been hurt by the company's plan to lay off 15% of its workforce, cutting some 14, 000 jobs, including contractors.

And four years into his tenure as CEO, Woods has become a divisive figure for many at the company, according to interviews with current and former Exxon employees from all levels and departments. He is criticized by some as lacking the blustery defiance and swagger of his predecessors in the corner office, and by others as not being more of a visionary change agent.

Woods insists that the company's strategy doesn't rely on higher oil prices. But he appears to be banking on the success of a classic Exxon tactic in times of trouble: push ahead and wait for the cost of a barrel to rise. The higher that crude goes-the price surged from $37 at the end of October to $68 as of late May-the better the odds that the strategy succeeds. And at a moment when the company arguably is under more pressure to change than at any point in its 135-year history, the bigger question is this: Does it even want to?

*****

WOODS SOUNDS RELAXED and confident. In a phone conversation with Fortune in early April, he is reflecting on the turbulence of the past year. Painful as it might have been, 2020 was “a pivotal year" for Exxon, he says, “not only because of what happened with the pandemic and the economy and the demand for the products that we produce, but it was also a time when I think several things came together. "The CEO and his leadership team had just completed a reorganization plan in the fall of 2019, he explains. And the fallout from COVID-19 pushed the entire organization to move faster. “The pandemic really accelerated the effort there and gave the organization a better understanding of the urgency.”

Exxon didn’t appear to be in need of a major overhaul when Woods succeeded Rex Tillerson as chairman and CEO on Jan. 1, 2017. Indeed, in Woods’ first full year at the helm, the company earned a hefty $19. 7 billion profit, and its “return on average capital employed”—a metric traditionally beloved by the company- was 9 %, or more than double that of the previous year. But its debt had risen sharply in the years before Tillerson's departure to serve a stint as secretary of state in the Trump administration. And it soon became clear, inside and outside the company, that Tillerson had left Woods with a mess to clean up. Among Tillerson's missteps: overpaying in the $35 billion acquisition or the Texas shale company XTO in 2010. when the shale boom was in full swing.

To jump-start growth, Woods adopted a quintessentially Exxon approach: He decided to bet on big projects that would pay off handsomely when oil prices rose. His reorganization plan called for the company to bump up operational spending by 30 billion to $35 billion every year through 2025, focusing on a "big five" of particularly promising, largescale oil and gas projects - from the Permian Basin in Texas to Guyana to Mozambique-- while selling off other assets. Woods projected that plan would result in a jump to s million equivalent barrels of oil per day, and double earnings, by 2025.

Then COVID-19 changed the math. Global oil demand in 2020 dropped a historic 8. 8 million barrels per day from 2019, according to the International Energy Agency, and prices fell even more dramatically. (The cost of a barrel even dropped briefly in trading to negative $38 per barrel in April 2020.)

Woods immediately slashed capital spending by 30% and said costs would be reduced by 6 billion through 2023. Exxon's dividend, however, was one cost that remained untouched. Unlike BP and Shell, which both reduced their dividends for 2020 in the wake of large losses, Exxon kept its payout steady-even borrowing to keep it fully funded.

And as he was leading the company through these challenges, Woods was struggling to find his footing with Exxon's workforce, according to current and former employees. His two forerunners in the CEO job were a tough act to follow as front men. Lee Raymond-who in 1999 orchestrated the merger of Exxon and Mobil, reuniting two off spring of J. D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, and led the combined company until 2005--was famously hard-charging. And Tillerson was a brash and charismatic leader in his own right. Woods, by contrast, is more publicly reserved. An Exxon lifer who studied engineering at Texas A&M, he is a product of the company's conservative, command-and-control culture and was regarded as sharp and straight talking when he landed the job. But his leadership style has failed to inspire some employees and rubbed others the wrong way.

As an example, current and former employees point to a disastrous town hall meeting about a year into Woods' tenure as CEO. Speaking off-the-cuff, Woods defended the company's rigidly competitive, deeply unpopular employee ranking system as meritocratic. He also related a story about firing a crying female employee, only for her to come back and thank him a year later for giving her the chance to pursue new opportunities, according to employees who saw the town hall. The meeting's overall effect was to give an impression of Woods as tone deaf and arrogant. Internally, the appearance was regarded as a "car crash,” says one former senior manager, and word spread rapidly within the company. In response to questions about the town hall, an Exxon spokesperson provided this statement: “Darren continues to engage and talk with employees on a regular basis, takes part in town halls, and listens to employee feedback and considers it as he leads the company.”

*****

ENGINE NO. 1 did not waste any time announcing itself to the world. On Dec. 7, the newly formed activist investment firm, with a bankroll of $250 million deployed in public markets, launched its very first campaign, with Exxon as the target. As an opening salvo, the fund said in a statement that “no company in the history of oil and gas had been more influential.”

but that “it is clear, however, that the industry and the world it operates in are changing and that Exxon Mobil must change as well.”

The San Francisco–based firm was founded by Chris James, a hedge fund veteran and cofounder of Partner Fund Management and Andor Capital Management. It’s backed in the Exxon campaign by some of the largest pension funds in the U. S. , and it asserts that Exxon’s board of directors does not include members with sufficient knowledge of the energy industry to lead a green transition. They have picked four candidates to join the board who, they say, have the right credentials. One candidate is the former CEO of Andeavor, the U. S. oil and gas company; another led the transformation of a Finnish energy company’s shift toward renewable fuel.

One might view the Engine No. 1 campaign as the most formidable challenge yet to Exxon’s long history of recalcitrance on climate change. Former CEO Raymond questioned the validity of climate change on multiple occasions. Under Tillerson, Exxon publicly acknowledged that climate change was real. But the Union of Concerned Scientists alleged in a report that, behind the scenes, the company was continuing to fund flawed research to muddy the science on the changing climate. Exxon says the report “deliberately misstates” its position on climate change, and that it “inaccurately” accuses trade organizations to which Exxon belongs of “so- called climate denial.”

The long shadow of Exxon’s record is reputational but also legal: The company is currently facing 20 lawsuits from local and state governments that are related to climate change, says Michael Gerrard, founder of Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. Gerrard says that makes Exxon “far and away” the top corporate defendant for climate change–related lawsuits in the U. S. So far, no such suits have been successful; in 2019, Exxon won a case brought by the New York attorney general, which alleged that the company had downplayed the risks it faces from climate change.

Woods himself has expressed a more open, transparent approach to addressing climate change. He has spoken frequently about the 2015 Paris Agreement, and devoted such long sections of investor presentations to the topic that even longtime critics have sometimes found it jarring. At one Exxon annual meeting, Woods spoke about the environment for the first 20 minutes, says Kathy Mulvey, the accountability campaign director in the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “If you were an alien dropped from outer space into that meeting,” says Mulvey, “you would have thought this was a company focused on solving climate change.”

But critics say that the kinder, gentler rhetoric on climate change isn’t matched by Exxon’s actions. Consider, for instance, the company’s claims that its emissions cuts are in line with the Paris Agreement. Exxon’s targets—to slash upstream emissions intensity by 15% to 20%, and methane intensity by 40% to 50%, by 2025—cover emissions only on projects that Exxon operates itself. (In 10-K filings, the company reported that about 13% of its wells are non-operated.) And they extend only as far as Exxon’s own emissions or energy used on those projects, known as operating emissions or “Scope 1” and “Scope 2.” BP and Shell have included targets for Scope 3, which covers the largest portion of emissions tied to oil and gas—those that come from burning the fossil fuels to power cars and airplanes. Exxon says it limits reporting to Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions because they are under the company’s direct control, and it’s clear how to report them, whereas Exxon argues Scope 3 emissions data is less consistent and can be misleading.

Woods has been dismissive of the more ambitious targets of his rivals. In a March 2020 call with investors, he referred to such targets by peers as a “beauty competition,” remarking that selling off oil and gas assets to a “less effective operator” has “actually made the problem worse.” Instead, Woods talks about solving the problem more “holistically.” In response to questions about the company’s approach to climate change, an Exxon spokesperson said that the company had invested more than $10 billion since 2000 in lower-emissions technology, and added: “We are committed to doing our part to address the risks of climate change and being part of the solution.”

But one former employee says ruefully that the true attitude inside Exxon is that consumers need its products, whether they like the company or not: “We don’t dress up our pig at all. We don’t even put lipstick on the pig. We just say, ‘Everyone likes bacon, so shut up.’”

Of course, even the more climate- friendly policies of Exxon’s European rivals may not be going far enough to make a meaningful difference. In a landmark report released in late May, the Paris-based International Energy Agency said that in order to have any hope of cutting emissions to net zero by 2050, no new investments must be made in oil and gas fields at all from now on—a pledge that none of the major oil and gas companies have made.

*****

WHEN IT COMES TO the question of what, exactly, an oil and gas giant should do about climate change, Exxon has come to a different conclusion. On Feb. 1, Woods announced the launch of a new business, Low Carbon Solutions, to commercialize technologies that Exxon has been developing. It will start, first and foremost, with carbon capture and storage, or CCS—a process in which carbon dioxide from burning or extracting fossil fuels is trapped and prevented from reaching the atmosphere. Woods said Exxon would invest $3 billion in Low Carbon Solutions from 2021 through 2025.

Engine No. 1 claims the company has changed its rhetoric on climate change in response to investor pressure. But Woods says the timing was simply right. Wind and solar power “while important” aren’t a “complete solution,” he says, and the company has been working on CCS technology for years. The aim is not just to offset their own emissions but to build out a new business: Given the explosion of net-zero commitments by companies, those same companies are going to need a way to offset their emissions, he says. There has also been, of course, a shift in the political winds.

“I think the Biden administration change, and the emphasis that they’re putting on that, put an accelerant in that process, and so really provided the underpinnings for us to take that work that we’ve been doing on technology and carbon capture and change that into a full-blown business.” says Woods.

But so far the new venture hasn’t announced any projects beyond what it had already made public. Experts and analysts also say that without new incentives, first and foremost a carbon tax—an option that Exxon Mobil has publicly backed since 2009—it is not currently economical to launch large CCS projects in the U. S.

Exxon doesn’t disagree. When it comes to making CCS projects profit- able, “I would say that the U. S. is not there in terms of incentive structure to make something like this happen.” says Guy Powell, who has led Exxon’s CCS ventures internally since 2018 and is now helping to lead Low Carbon Solutions. “But we do see potentially the political will to put in the right incentives, regulatory and legal structures in place, to make that happen.” The company is engaging with policymakers, Powell said, and has other projects in the works.

While Exxon asserts that it is the world’s leader in capturing CCS, critics argue that the expertise comes with a catch: The company’s approach is focused on “enhanced oil recovery,” a method that injects CO2 into the ground in order to push more oil out, rather than solely long-term sequestration for the explicit purpose of reducing carbon emissions.

Powell says that, indeed, most of the current CCS efforts in the U. S. are for the purpose of oil extraction, and that the technique, used by the oil and gas industry for decades, requires “different applications of technology and operations” than long-term sequestration. But he argues that the end result is the same. “It is a different process, but the net result is that the CO2 stays securely in the ground,” says Powell.

Some industry analysts are openly skeptical about the value of the new venture. “It’s more than a concept, but it’s a direction rather than a big capital shift,” says Alastair Syme, a managing director at Citi who follows Exxon. “I would interpret that as part of the lobbying effort.”

*****

IN THE MONTHS since Engine No. 1 went public with its proxy battle against Exxon, the stakes of the showdown between the fund and the energy giant have steadily been raised. In what appears to be a direct response to Engine No. 1’s proposed slate of new directors, Exxon has added three new members to its board since the start of the year, including the former CEO of the Malaysian state energy company as well as activist investor Jeffrey Ubben, the founder of the San Francisco–based hedge fund ValueAct Capital.

But Engine No. 1’s campaign continues to gain supporters. It has been backed publicly by three of the largest pension funds in the U. S. —Calpers, Calstrs, and the New York State Common Retirement Fund—as well as Legal & General, a U. K. asset manager with more than $1 trillion in assets. Four major proxy advisers, including Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass Lewis, the two largest voting advisories in the U. S. , have offered Engine No. 1 support for at least some of its proposed board members. Said Glass Lewis in its report: “While Exxon claims to have evolved its strategy and maintained its historical leadership position among oil majors, our review finds the company’s competitive position and financial returns have eroded, and its stated strategy to address the underlying reasons for this diminished performance is generally insufficient.”

The night before the vote, the campaign won another coup when Reuters reported that BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, had voted for three of Engine No. 1’s four candidates. The success of the vote would hinge on the support of other institutional giants Vanguard and State Street.

Woods has been aggressive in making his case. Responding to a question from an analyst in the first-quarter earnings call, the CEO staunchly defended the expertise of Exxon’s current board, and said the company has changed how it engages with shareholders. “I think we are responding to the feedback that we get.” he said.

Engine No. 1 says that Exxon has missed an opportunity to have a serious debate over what should be done about climate change in the long term. Before the campaign, “Exxon’s proud answer was nothing.” says Charlie Penner, head of active engagement at Engine No. 1 and the leader of the Exxon proxy battle. “But once there was a risk of losing board seats, rather than having that debate, they just threw on the other team’s uniform”—that is, an energy-transition uniform—“and tried to avoid it.”

Will the campaign force real change at Exxon, even if it doesn’t unseat any board members? Industry observers are divided. Some say it has served as a warning shot that the world is changing, and Exxon is not immune. Others say it’s likely that the oil giant will get back to business as usual—especially if oil and gas prices continue to rise, driving up the value of Exxon’s shares in the process. As of late May, Exxon’s stock was up 41% since the start of the year.

When asked what questions Exxon employees ask him about the future of the company, Woods is circumspect. “The questions internally are very consistent with the external questions.” he says, “which is, you know, given the demand and the desire for less carbon intensive energy sources, how does that demand realize itself with time? And what’s the impact on the company? And how do we think about managing through that transition?” He continues in a reassuring tone: “Our job here is to meet the evolving demands of society. And that’s what we have historically done.” Just don’t rush him.