本文的报道得到了NIHCM Foundation的资助。

即便与过去18个月的大环境以及美国人遭受的巨大痛苦相比,约翰•菲利普和乔迪•菲利普夫妇的处境依然十分艰难。

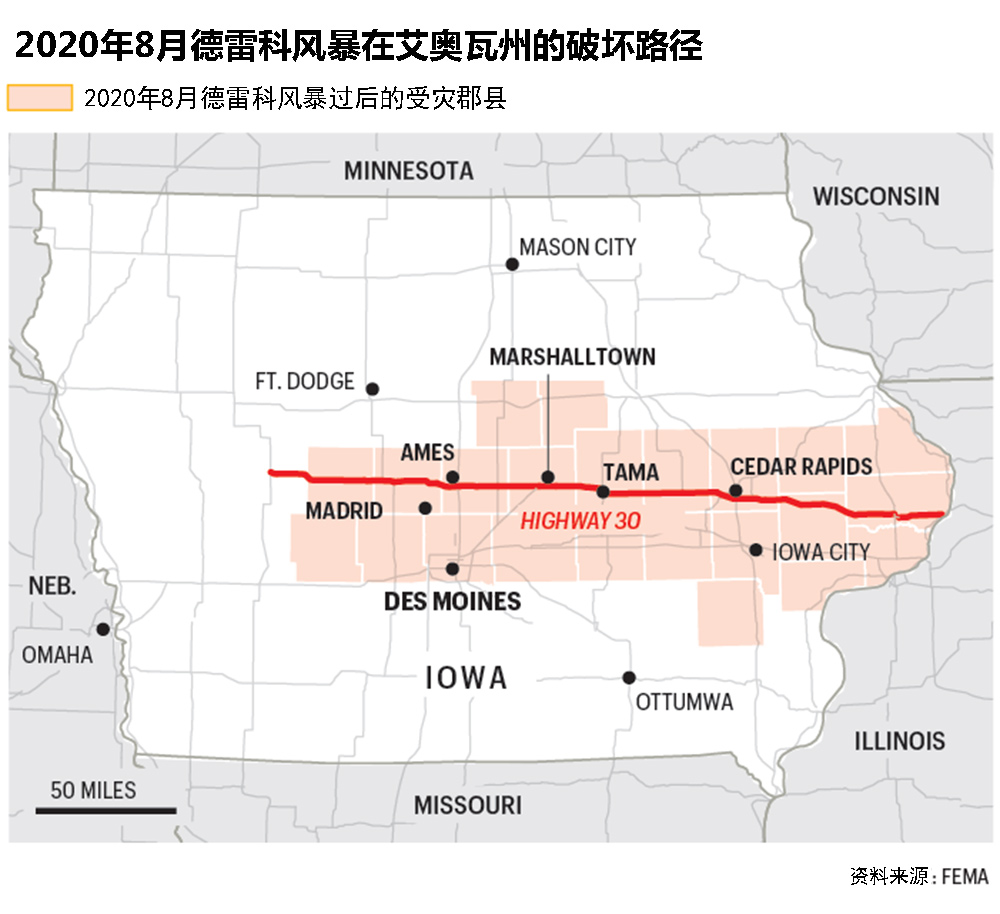

他们都出现了非常严重的健康问题,乔迪是脑肿瘤,而约翰是四期癌症(在经历了数次中风之后于2019年11月确诊)。自2020年年初新冠疫情爆发以来,这对夫妇位于艾奥瓦州的乡村生意——2 Jo’s Farm和Periwinkle Place Manor庄园——因为旅游和聚会活动受限,也受到了很大的影响。随后在8月10日,就在乔迪从艾奥瓦大学(University of Iowa)接到在那里完成癌症治疗的约翰,准备返回位于范霍恩的家中时,这个约有900人的小镇遭到了罕见的德雷科风暴袭击。当天发生的这场风暴在美国中西部留下了长达1200多公里的废墟地带,而且将被作为历史上代价最为高昂的风暴载入史册。

他们停下车,车辆在倾盆大雨和超级狂风(阵风高达140英里/小时)的肆虐下咯吱作响,乔迪说:“我们觉得自己要挂了。”当时,他们收到了儿子从农场发来的各种信息和多个电话,然后儿子那边的信号断了,发来的最后一条信息是:他们得为此“做好准备”。

这个通常50分钟的车程最终耗费了数个小时的时间。一路上就像是在观看有关风暴破坏力的完整预告片:目之所及全都是被毁的谷仓、吹倒的庄稼,和散落再马路上的筒仓。

即便如此,乔迪在看到农场的情形之后还是感到一阵眩晕。他们的农场靠近30号高速公路(Highway 30,老林肯高速路),位于艾奥瓦州农村地区本顿县,占地13英亩。

菲利普一家的农场并非是传统的艾奥瓦州农场。这对夫妻数十年来一直在美国中西部地区的一些地方和节日聚会上扮演圣诞老人和圣诞老奶奶,饲养驯鹿,而且还养了一只名为克林格的骆驼。他们还在农场建造了一个西部小镇,以及一个骑马场。德雷科过后,农场建筑被夷为平地。大部分树木都被吹倒了,房屋和车库受到的破坏异常严重,一时半会也很难清点。她说,这个地方已经没法住了,而且大多数受损的个人物品都已经无法维修。当我第一次与她交谈时,她对我说:“我到现在依然无法接受这个事实。当我们回到农场后,只是走来走去,焦虑的想着下一步该怎么办?”

这段对话发生在1月初,当时,乔迪一天要去范霍恩两次,给动物们喂食和喂水。她和约翰住在驱车30分钟以外的地方,照看着另一门生意Periwinkle Place Manor庄园,这里此前是一家殡仪馆,他们在数年前将其买了下来,然后装修成了一家提供住宿与早餐(或死亡与早餐,乔迪微笑着推销道)的谋杀悬疑剧院。

这座庄园是一个维多利亚式的宅邸,修建于19世纪末,位于艾奥瓦州切尔西镇,镇里有300位居民。该镇位于林肯高速路(Lincoln Highway)的另一侧,地势低洼,易发洪水。所以,在数十年前,城市议会曾经投票将切尔西镇搬到地势更高的地方,但未成功。德雷科风暴来袭时,这个小镇也未能幸免于难,其图书馆成了牺牲品,但这座庄园仅遭到了轻微的破坏(其电力却中断了两个半月),而这对夫妻、其26岁的智障女儿和一条狗就住在这里。72岁的约翰和62岁的乔迪是在去年11月患上新冠肺炎后搬过来的。乔迪很快恢复了,然后在12月又接了几单扮演圣诞老奶奶的活,但约翰因为肺部血栓和肺炎,在医院住了一个月的时间。这是乔迪去年第三次觉得约翰可能会不久于人世,庆幸的是约翰在圣诞前夜回到了家中。

然而,尽管一家人在2020年遭受了几乎不可估量的损失,但乔迪并未觉得今年就能够好到哪里去。在这些事情发生以及恢复举措开始实施之后,事情却变得越来越糟糕。

主要原因在于乔迪与其财产保险公司之间的纠纷。乔迪单方面称双方之间的较量已经成为了长达数月,且令人沮丧、疑惑、孤单以及越发绝望的拉锯战。到目前为止,围绕与德雷科相关的赔偿,保险公司向不动产支付了212,525.43美元,而这是被摧毁的骑马场几乎可以获得的所有赔偿,仅占损失总额的一小部分,而且乔迪及其聘请的专家也认为,根据她与约翰所签署的这份67.3万美元的保单,这笔赔偿额也只是其中的一小部分。她在农场的住所依然破败不堪,日晒雨淋,仅得到了不到29,663.13美元的赔偿款。目前,一家人依然居住在Periwinkle Place Manor庄园,而庄园的周围则是一片狼藉。

乔迪说:“我们曾经以为自己买了很不错的保险,而且很多年来都是如此。今年的日子不好过,我们也已经向这家保险公司交了20多年的保费,而且从未出过险,但它却彻彻底底地背弃了我们,在我看来,这种行为就是犯罪。”

去年,我偶然看到了一位家族朋友代表菲利普夫妇在GoFundMe的网页上发布的信息后,才开始与乔迪接触。当时,我在撰写一篇报道,内容是我的家乡艾奥瓦州是如何应对德雷科和新冠疫情这一双重灾害。由于约翰刚刚出院,我本以为这对夫妻与新冠肺炎的斗争将成为我们讨论的主题,然而即便约翰依然在忍受着新冠肺炎后遗症的折磨,但很明显,乔迪所面临的最大压力在于,其农场当前局面让她感到异常的无助。

当我们在3月再次交谈时,事情仍然没有什么进展。6月依然是如此,不过,处于绝望边缘的乔迪希望引起外界对其困境的关注(一位邻近城镇的汽车经销商便成功地采用了这一策略),她用360美元定制了亮橙色条幅,然后将其张贴在自家沿高速公路修建的篱笆上。这些条幅上印着三个标语,控诉了本顿互助保险协会(Benton Mutual Insurance Association)以及负责理赔的第三方管理公司NCP Group在此事上的处理方式给她造成的不幸。这些条幅如今已经被摘了下来。

作为对菲利普一家控诉的回应,本顿互助称自己无法对单个索赔案例进行评论,NCP Group亦称自己无权进行评论,因为它只是第三方理赔管理机构,并不是菲利普一家的承保人。

漫长的恢复之旅

在艾奥瓦州,像菲利普夫妇这样依然在努力解决风暴灾害索赔问题的艾奥瓦人还有成千上万,而行政赔偿流程通常只是房屋所有者回归正轨需要做的首项工作。他们还在与时间赛跑,因为在这个将自己标榜为美国新保险之都的艾奥瓦州,大多数保单理赔起诉的诉讼时效仅有一年的时间。一些人称,尽管诉讼成本高昂,但这是消费者与承保人发生纠纷时唯一的求助途径。

今年,艾奥瓦州的恢复进程因为全球新冠疫情、一系列自然灾害和疫情导致的物资短缺而放缓,而且还变得更加复杂。乔迪和众多艾奥瓦人不得不应对恢复过程中的重重官僚主义障碍,这些压力给他们造成了第二次创伤。

但这个故事讲述的不仅仅是一对夫妻的艰辛,或是与某家保险公司打交道时出现的一次不愉快经历,亦或是一次恐怖的自然灾害之后混乱不堪的状况。德雷科,连同那些受损的房屋以及被掀翻的屋顶,暴露了整个保险行业存在的根本性问题。随着气候变化和导致银行资源枯竭的灾难给保险行业赖以生存的商业模式带来前所未有的压力,一些人认为保险行业已经变得越发不利于房屋所有者,而且无法提供普通人认为他们理应提供的保障。

灾害过后出现的类似纠纷并不是什么新问题。受委屈的投保人正是罗格斯大学(Rutgers University)的法学教授杰•费恩曼《拖延,推卸,辩解》(Delay, Deny, Defend)一书的主角。该书认为,一些财险企业为了提振其利润(根据管理层咨询师制定的手册),制定了多种策略来削弱人们的意志、情感能量和必要的资金,从而使其难以从承保人那里获取理所应当的赔偿。费恩曼对我说:“对于有效的索赔,现在获得赔付的难度要高于25年之前。”

飓风“桑迪”(Hurricane Sandy)对道格拉斯•奎恩在水滨区的房产造成了严重破坏,在遭遇上述令人沮丧的不公平待遇之后,当时从事金融顾问工作的他成立了美国投保人协会(American Policyholder Association),旨在阻止保险行业的欺诈行为。他说,这些斗争中的权力动态严重偏向了有着万亿美元规模的保险行业。奎恩说:“这是风暴后的风暴,而且在我看来,真正的狠角色并非是自然界的风暴。”他还表示,从险企使用老套的威吓策略到尝试通过在其Xactimate软件(保险理算员用其来给理赔定价)上刻意录入较低的实际价格来欺骗投保人,自己遭遇过的这些套路正在艾奥瓦州上演,更不用说那些曾经遭遇过自然灾害的其他地区。奎恩说:“全美各地都能够看到这样的事情。”

从其涉及的范围来看,保险行业对这类控诉根本不屑一顾,并将之视为原告律师的自私行为,而且通常根源在于消费者在灾害来临之前并没有完全理解其保单条款。作为对本人疾呼的回应,各大险企强调自己是本着关爱的态度来处理索赔,并兑现其保单中承保事项的承诺。保险信息研究所(Information Insurance Institute)也鼓励人们通过询问问题和认真筛选,去了解保单中的具体内容;该机构还警告,即便选择最便宜的保单,也要认真阅读其承保范围。保险信息研究所的媒体关系总监斯科特•霍尔曼对我说:“不要试图买辆破车,还奢望在理赔后可以换一辆凯迪拉克(Cadillac)。”

NCP Group的副总裁大卫•斯特灵在评论纠纷时笼统地说:“作为理算师,我们在这个非常脆弱、紧张、恐怖的时期参与处理投保人的理赔事宜,其中很多人以前从未提出过索赔。NCP Group希望我们协助的所有投保人都能够获得其保单允许的全部赔偿额。有时候,理赔需要进行进一步的调查;有时候需要进行额外的勘验;甚至有时候还需要进行额外的讨论。这些举措会给投保人带来更大的失望感,然而,我们将尽自身所能,尽快地妥善做好理赔工作……在应对投保人方面,最大的一个问题在于他们会期待保险公司支付保单之外的赔偿。NCP Group的委托方要求我们在给客户做出任何推荐时必须遵守保单条款。我们将付出更多的努力,来确保不会出现任何遗漏,但我们无法更改投保人的保单条款。”

不管怎么样,气候变化和不断增加的极端天气频率意味着保险公司与投保人之间的纷争只会变得更加频繁和激烈(更不用说与之相关的成本,以及各有关方面在面对新现实时的不知所措),而且越来越多的人有可能会得不到保险保障的保护。

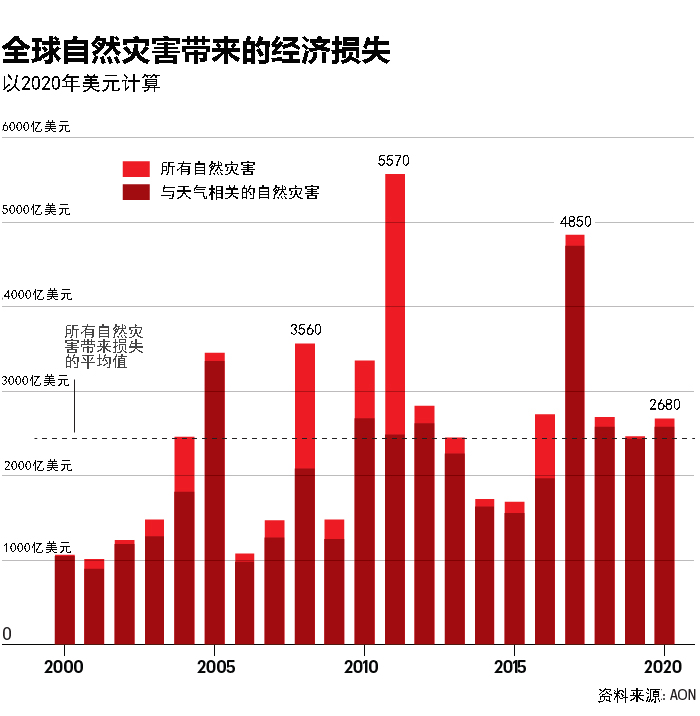

当然,有关气候风险破坏性的证据已经是异常明了。美国国家海洋和大气管理局(National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)的数据显示,2020年,美国遭受的破坏性天气和气候灾害创下了历史纪录,损失超过10亿美元的事件共有22起,“打破了之前16起的年度纪录”。2020年因为此类事件而引发的投保人损失达到了730亿美元,较过去20年的平均值高出82%(扣除通胀因素)。

霍尔曼在写给《财富》杂志的电子邮件中称:“我们看到,因为自然灾害而引发的投保人损失的增速已经达到了警戒水平,自20世纪80年代以来增长了近700%。”邮件还指出,去年发生了创纪录的亚特兰大飓风和西部山火季(在加利福尼亚州史上最大的六场山火中,有五场就发生在去年)。“然而,保险行业在这些极具破坏力的事件中展现了领导力,向投保人支付了赔偿。”

他注意到,尽管保险公司数年前便已经将气候风险融入其业务模型,但“2020年展现了这种破坏性事件的发展态势。”

事实证明,2021年也是一个多灾之年。截至7月9日,根据美国国家海洋和大气管理局的统计,美国今年已经出现了8起损失10亿美元的天气和气候灾害。除了经济损失之外,这些灾害还造成了至少331人死亡,其中包括此前无法想象的灾害,例如得克萨斯州长达10日、造成巨大破坏的冬季冻灾,以及太平洋西北岸创纪录的热浪。

德雷科的破坏力亦超出了人们的想象,去年8月数小时内就给美国中西部地区造成了约115亿美元的损失,其对艾奥瓦东部的破坏尤为严重,在那里,高强度风力所导致的破坏远超天气预报员或保险精算师的想象。在这个有着近25.8万人口的锡达拉皮兹,几乎所有的家庭都因为风暴而出现了一定程度的损失。在酷热的8月,很多人失去电力长达一周的时间,还有些人停电远超一周。全球职业服务公司怡安(Aon)的灾害洞见业务负责人史蒂夫•博文说:“德雷科真的是让很多人大开眼界,原来雷暴也可以带来飓风级别的损失。”他表示,该地区的不动产,不管是全新的还是数十年前的老建筑,在修建时都没有考虑过这种级别的风速。博文称:“它在提醒人们,即便在过去不大会被看作能够造成重大破坏的危险如今正在越发成为一种更高级别的风险。这场风灾让众多人感到措手不及。”

确实,艾奥瓦州并没有为这种飓风级别的灾害损失做好准备。与发生野火的乡村以及飓风经常光顾的沿海各州相比,艾奥瓦人在大规模自然灾害面前相对来说缺乏经验,而且长期以来,有着丰富实战经验的美国各州在应对此类灾害时已经积累了有力的基础设施和专长,而这正是艾奥瓦州的短板。艾奥瓦州对保险理算员没有许可要求,意味着任何人都可以从事为险企评估损失的工作。

寻求帮助

同时,支持投保人索赔,或与保险公司发生争议时的资源很少。要从事公共理算或作为投保人(而不是保险人)的独立辩护人,确实需要许可证,而且艾奥瓦州提供服务的人相对较少(佛罗里达则有数千人)。同样,专门研究灾害相关保险损失的律师也寥寥无几。在非营利组织United Policyholders的网站上,艾奥瓦州的“寻求帮助”资源页面只列出了一家公共理算师机构——斯威夫特公共理算师公司(Swift Public Adjusters)和一家律师事务所——拉鲁律师事务所(Larew Law Office),资源页的列表均由赞助商提供。

詹姆斯•拉鲁曾经于2007年至2011年期间担任艾奥瓦州州长切特•卡尔弗的法律总顾问,他发现很多人不会跟财产保险公司和意外伤害保险公司打交道,又无处求助(他们经常希望找州长反映问题),2011年他开始支持投保人。拉鲁在艾奥瓦州出生长大,他表示当地人倾向于自行承担责任,也就是说在赔付问题方面不太可能挑战保险公司。他和其他人认为,即便真去挑战,州政府也不愿意面对,因为法律和政策倾向行业(举例来说,即便打赢官司,艾奥瓦州人也必须自行支付法律费用。州政府允许保险公司在合同中注明时效期限,最短只有一年,而州内书面合同常见时效为10年。)

此外,房屋受灾的人们处境本就艰难,诉讼又耗时费力。拉鲁说,保险公司知道自己被起诉的风险很低,所以才敢向投保人支付较低的费用还不担心后果。

7月底我与艾奥瓦州保险部(Iowa Insurance Division)的专员道格•奥门交谈时,保险公司已经为本州22.5万起与德雷科有关的索赔支付了30多亿美元。未决索赔约18000起,占总数8%。奥门说,从这一数量可以看出损失的规模以及劳动力和材料多么短缺。艾奥瓦州保险部已经收到392起与德雷科有关的投诉,其中大部分已经由该机构调查并结案。相关投诉中,110起被证实主要是由于“索赔过程延误以及财产核查过程中的损失”,结果是向该州投保人多支付了30.7万美元。收到《财富》杂志的询问后,艾奥瓦州保险部还发布了一份公告,建议保险公司考虑保险理算员紧缺等拖累很多人恢复的各种情况,接受延期的请求。至少有一位公共理算公司表示,多数情况下保险公司会继续拒绝延期。奥门表示,办公室正在调查德雷科导致的问题,比如允许保险条款限期一年是否合理。

常见创伤

灾难来临时,房主保险应该是好事。保险信息研究所的数据显示,20世纪50年代房主保险开始商业化,用来避免家庭受到火灾和龙卷风等改变生活且破坏财富事件的影响,很快抵押贷款机构将之列入要求,如今93%的美国房主都购买了保险。虽然标准家庭保险并不涵盖地震和洪水等灾难性事件,但通常涵盖风灾造成的损失,意味着私人保险公司应该为多数艾奥瓦州的房主因为德雷科而遭受的损失负责。

1月,艾奥瓦州国土安全和应急管理部(Iowa Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management)的恢复司司长丹尼斯•哈珀告诉我,正因如此,本州才可以迅速恢复。“[私人保险公司]能够立刻介入并提供资金。”他告诉我,此举帮助房主启动维修和恢复过程。虽然由于新冠疫情蔓延,还有德雷科导致的大范围停电,相关工作有些复杂,但对多数人来说,复苏的道路相对清晰,资金充足(哈珀解释说,相比之下,艾奥瓦州偶尔遭逢洪灾影响时,60%到70%的受影响者往往损失险覆盖不足,甚至没有保险。)

事实上,很多艾奥瓦州人在风暴过后生活比较顺利。例如,我的父母住在锡达拉皮兹,在保险公司拒赔而承包商挑战成功后,获得了新屋顶,他们觉得待遇还算公平。1月跟当地人和官员交谈后,我感受到强大的保险保障和艾奥瓦州融洽的邻里关系(人们手持电锯帮助邻居),受德雷科影响的社区做得相当好,或者至少在逐渐推进,只是由于破坏规模太大,恢复的过程漫长而艰难。

但随着时间推移,很明显我了解到的情况并不够全面。有很多像乔迪一样的房主,尽管付出了相当大的努力,还是发现自己困在过程中,保险公司的服务很差,然而保险公司至少理论上应该提供保障。有些案件涉及我的朋友和家人;还有很多像SOS求救信号一样发表在Facebook页面上,例如艾奥瓦州德雷科风暴资源页面(Iowa Derecho Storm Resource Page)和艾奥瓦州保险索赔问答页面(Iowa Insurance Claim Q&A),风暴后各种类似页面形成了支持网络。两个群组都有数千名成员,除了正常交流,也跟美国州立农业保险(State Farm)、好事达(Allstate)、本顿互助、NCP Group和其他很多保险公司交换协议信息。当时很多人感到愤怒。在跟一些人交谈中,我了解到人们的经历各有各的复杂之处,但有共同的创伤:一种无力感,一种被大肆自称好邻居的行业背叛的感觉。人们感觉被困在保险公司制造的迷宫中。

52岁的宝洁(Procter & Gamble)员工丽贝卡•约德就是个例子,她和丈夫住在锡达拉皮兹,表示自己的经历是“彻头彻尾的噩梦”。为了财产索赔,她不得不跟五位现场理算员和好事达的很多内部理算员打交道,人数多到“数不清”。她的感觉是,理算员们根本没有相互交流,也没有人利用她提供的丰富文件,包括150张照片和一份详细的损坏清单。整个过程中,她感到“被忽视、被欺骗、只感觉自己很愚蠢”。她表示,屋顶还在漏水需要更换,但好事达只同意修补(她说,到访五名理算员中没有一人真正登上屋顶认真检查。)同时,好事达同意更换屋顶之前,承包商不愿意给她报价。即便后来她找到了愿意报价的承包商,但最终还是被放了鸽子,雇佣的油漆工和公共理算师也不见了(我了解到,对受德雷科影响的房主来说,相关人员突然消失是常见的问题)。刚开始,好事达为这对夫妇支付了略高于1万美元的赔偿金;经过不懈跟进,约德在一位公共理算师的帮助下收到了2万多美元,还是不到公共理算师估算金额的一半。

“情绪上的影响非常大。”她在给我的信中说。“先是让我们满怀希望,为了会面和电话打乱日程安排,很不方便。最后有些工作都是自己做的,因为自己掏腰包雇不起人,实在令人沮丧。”约德还在盼着好事达可以帮忙修房顶。整修完成之前,很难想象未来。“现在,我们身陷困境。”

在一份电子邮件声明中,好事达表示已经根据客户索赔“及时全额赔付”,并且“正积极努力解决余下异议,彻底调查所有未决索赔,以确保准确及时地赔偿客户。”该公司指出,已经解决了艾奥瓦州98%与德雷科相关索赔,为客户提供的损失补偿超过1.2亿美元。

玛丽•汉考克位于锡达拉皮兹东南部的家中,风暴将一棵树砸在了她的房上,导致车库和住所受损,比起多数人,她对自己驾驭局势的能力信心更足。作为房地产经纪人,她非常了解保单的细节和繁琐的索赔流程。但近一年后,她惊讶地发现处境与约德相似,车库仍然无法正常使用,屋顶需要维修。一下大雨,水就会渗到家里,导致破坏情况更严重。收到1.2万美元赔付款后,她和丈夫感觉相当不容易,因为第一位理算员告诉她,财产并没有问题;第二位探访后支付了4000美元,还是也远低于她认为根据保单应得的金额。“我们不在佛罗里达。”她说,对眼前情况还是有点惊讶。“多年来一直在收保费,(现在)支出却很少。”

汉考克来自西非的多哥,她认为歧视导致自家斗争更加艰难,于是她专门聘请了一位公共理算师,她注意到自己帮助过的移民家庭也有类似做法。至于她自己的战斗,几乎要认输。“我没有精力去对抗结构非常完善(且对保险公司有利)的体系。”7月底她告诉我,并补充说她和丈夫计划为房子再筹集资金,用来填补保险赔偿金不覆盖的部分。

约翰和乔迪的故事是另外一个具体而复杂的案例。两人损失和处境都很极端,但据处理过德雷科案件的人说,两人与保险公司的斗争方式跟其他人差不多。20多年来,约翰和乔迪通过本顿互助保险协会(Benton Mutual Insurance Association)购买了认为价值100万美元的房主保险,该协会1872年就已经成立,是众多服务于艾奥瓦州农村社区的农场小型互助社之一。协会总部位于艾奥瓦州基斯顿,在范霍恩西面10英里,为艾奥瓦东部19个县提供家庭和农场保险。德雷科当天,超过一半的投保人受到影响。像许多房主一样,约翰和乔迪对保险没有太多考虑,刚开始保险通过附近另一个城镇文顿的代理商购买,并且每年续保。保单的年保费为1718.30美元,涵盖了夫妇的住宅、车库、骑马场和个人财产。

夫妇从未提出过索赔,因此在德雷科发生后乔迪惊讶地发现实际上有一份价值67.3万美元的保单,但对屋顶附有限制性说明,声明本顿互助“不支付风暴或冰雹造成的屋顶损失,除非进行了可接受的维修或安装了新屋顶。”《财富》杂志看到关于屋顶的说明日期为2017年8月,约翰•菲利普的名字已经印上,还有保险代理人的签名,写着“上午10点18分通话确认。”约翰和乔迪都对跟代理人就相关说明谈话毫无印象,更别提同意。(多次评论请求均未获保险代理人回应;本顿互助也拒绝对个人索赔发表评论。)

菲利普聘请的公共理算师和律师表示,该合同是纠纷的关键,因为本顿互助认为,已经免除了对屋顶损坏或房屋内因为屋顶受损而影响物品的赔偿责任。这也反映了律师、United Policyholders的执行董事艾米•巴赫称之为保险业“有问题”的趋势,即悄悄修改房主的保单。United Policyholders是非营利组织,1991年成立,艾米•巴赫是该机构的联合创始人。

“由于与气候变化相关的风暴和水灾事件越来越多,保险公司越发积极限制屋顶损坏和屋顶维修费用。”她解释说,这一做法开始于2013年左右。“这一问题在艾奥瓦州引起广泛关注,因为类似德雷科的情况下,既涉及风暴又涉及大雨。”

巴赫说,调整通常不会与投保人明确沟通,而且实施得太迅速,房主和监管机构都跟不上。条款调整实际上降低了房主保单的价值,成本却很少降低(奥门说,这是艾奥瓦州保险部根据德雷科正在研究的另一问题。)2020年巴赫的组织发起了一项全国性倡议,即重建保险安全网联盟(Restoring the Insurance Safety Net Coalition),希望呼吁监管机构、官员和法院意识该问题并制定标准,防止保险公司过分缩小范围。毕竟,如果房子没有屋顶,那价值何在?

根据NCP Group(总部位于佛罗里达州,本顿互助委托该公司评定和处理索赔工作)编写的报告,菲利普夫妇发现其实价值很少。保险公司认定三层农舍赔偿金或实际现金价值仅为16786.17美元。“简直滑稽。”乔迪告诉我。“他们愿意(赔的钱)只够给天花板塌着的屋子刷刷墙。”尽管进行了上诉,也有乔迪聘请的公共理算师的帮助(理算员评估保险赔偿金超过67.3万美元的保单),但据乔迪和代理人所知,NCP Group并未另派理算员重新核查。第一位理算员已经不在NCP工作。(NCP不评论个人索赔。)

公共理算师为该房产争取了几笔额外赔付,但与巨额估算相差甚远。种种努力停滞不前时,乔迪与公共理算师的关系也迅速恶化,而双方合作曾经是给了他们巨大的希望。她从公司也得不到答案。

和我采访的其他人一样,乔迪让我感觉到,理赔过程中最令人不安的部分是缺乏人性:个人遭受巨大损失和创伤时,可依赖的人不回电话也不回短信;沟通也很差,甚至无法沟通;理算员、承包商或公共理算师会突然消失,有时还会被随意换人重新走流程。大灾难之后似乎都是此种模式,就像这一次,然而明明时间和资源都很匮乏。

就在此时,乔迪返回Facebook上的一个德雷科群组,找到了年轻而精力充沛的律师格雷格•厄舍,厄舍在锡达拉皮兹地区长大,后来从事财产和伤亡索赔。到2021年年初,他每周都要接8到10个求助电话,每晚等到年幼的儿子上床睡觉后仍然要工作。回顾诸多问题后,他得出了令人沮丧的结论:“几乎每个人情况都很糟。”6月初,当我们谈起过去一年时,他显得筋疲力尽又很愤怒,他滔滔不绝讲述了大保险公司糟糕的做法,还有遇到令人不安的事。他有一位名叫贝基•哈德森的客户,房子被压在树下,经营家庭日托中心的地下室也被污水淹没。她跟好事达的多位理算员打过交道,其中一人建议她好好清理,而不是更换污水泡过的日托用品。厄舍认为,好事达少赔了她至少10万美元。(好事达表示,已经迅速支付了索赔中无争议的损失,并且“所有未决索赔都经过彻底调查,以确保客户及时准确收到赔款。”)

现在他通过评估指导菲利普一案,走的纠纷解决流程,虽然并非没有风险,但比诉讼更快成本也更低。他说,准备在对菲利普家的财产联合检查时,与本顿互助的律师积极沟通下。虽然乔迪的案子离解决还有点远,但现在由于厄舍介入,感觉有些希望。而她描述的悲惨篇章,也是“最糟糕的一年”,似乎慢慢走向尾声。最近几周,乔迪获得了切尔西市议会的批准,骆驼克林格和驯鹿搬到了Periwinkle Place Manor庄园。她正在整修房子,方便夫妇二人搬回去,又开始主持谋杀悬疑剧院活动。她开始接受可能再也不会住在农场,只是努力记住,除了保险大战和过去一年的困境,前方还有未来。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

本文的报道得到了NIHCM Foundation的资助。

即便与过去18个月的大环境以及美国人遭受的巨大痛苦相比,约翰•菲利普和乔迪•菲利普夫妇的处境依然十分艰难。

他们都出现了非常严重的健康问题,乔迪是脑肿瘤,而约翰是四期癌症(在经历了数次中风之后于2019年11月确诊)。自2020年年初新冠疫情爆发以来,这对夫妇位于艾奥瓦州的乡村生意——2 Jo’s Farm和Periwinkle Place Manor庄园——因为旅游和聚会活动受限,也受到了很大的影响。随后在8月10日,就在乔迪从艾奥瓦大学(University of Iowa)接到在那里完成癌症治疗的约翰,准备返回位于范霍恩的家中时,这个约有900人的小镇遭到了罕见的德雷科风暴袭击。当天发生的这场风暴在美国中西部留下了长达1200多公里的废墟地带,而且将被作为历史上代价最为高昂的风暴载入史册。

他们停下车,车辆在倾盆大雨和超级狂风(阵风高达140英里/小时)的肆虐下咯吱作响,乔迪说:“我们觉得自己要挂了。”当时,他们收到了儿子从农场发来的各种信息和多个电话,然后儿子那边的信号断了,发来的最后一条信息是:他们得为此“做好准备”。

这个通常50分钟的车程最终耗费了数个小时的时间。一路上就像是在观看有关风暴破坏力的完整预告片:目之所及全都是被毁的谷仓、吹倒的庄稼,和散落再马路上的筒仓。

即便如此,乔迪在看到农场的情形之后还是感到一阵眩晕。他们的农场靠近30号高速公路(Highway 30,老林肯高速路),位于艾奥瓦州农村地区本顿县,占地13英亩。

菲利普一家的农场并非是传统的艾奥瓦州农场。这对夫妻数十年来一直在美国中西部地区的一些地方和节日聚会上扮演圣诞老人和圣诞老奶奶,饲养驯鹿,而且还养了一只名为克林格的骆驼。他们还在农场建造了一个西部小镇,以及一个骑马场。德雷科过后,农场建筑被夷为平地。大部分树木都被吹倒了,房屋和车库受到的破坏异常严重,一时半会也很难清点。她说,这个地方已经没法住了,而且大多数受损的个人物品都已经无法维修。当我第一次与她交谈时,她对我说:“我到现在依然无法接受这个事实。当我们回到农场后,只是走来走去,焦虑的想着下一步该怎么办?”

这段对话发生在1月初,当时,乔迪一天要去范霍恩两次,给动物们喂食和喂水。她和约翰住在驱车30分钟以外的地方,照看着另一门生意Periwinkle Place Manor庄园,这里此前是一家殡仪馆,他们在数年前将其买了下来,然后装修成了一家提供住宿与早餐(或死亡与早餐,乔迪微笑着推销道)的谋杀悬疑剧院。

这座庄园是一个维多利亚式的宅邸,修建于19世纪末,位于艾奥瓦州切尔西镇,镇里有300位居民。该镇位于林肯高速路(Lincoln Highway)的另一侧,地势低洼,易发洪水。所以,在数十年前,城市议会曾经投票将切尔西镇搬到地势更高的地方,但未成功。德雷科风暴来袭时,这个小镇也未能幸免于难,其图书馆成了牺牲品,但这座庄园仅遭到了轻微的破坏(其电力却中断了两个半月),而这对夫妻、其26岁的智障女儿和一条狗就住在这里。72岁的约翰和62岁的乔迪是在去年11月患上新冠肺炎后搬过来的。乔迪很快恢复了,然后在12月又接了几单扮演圣诞老奶奶的活,但约翰因为肺部血栓和肺炎,在医院住了一个月的时间。这是乔迪去年第三次觉得约翰可能会不久于人世,庆幸的是约翰在圣诞前夜回到了家中。

然而,尽管一家人在2020年遭受了几乎不可估量的损失,但乔迪并未觉得今年就能够好到哪里去。在这些事情发生以及恢复举措开始实施之后,事情却变得越来越糟糕。

主要原因在于乔迪与其财产保险公司之间的纠纷。乔迪单方面称双方之间的较量已经成为了长达数月,且令人沮丧、疑惑、孤单以及越发绝望的拉锯战。到目前为止,围绕与德雷科相关的赔偿,保险公司向不动产支付了212,525.43美元,而这是被摧毁的骑马场几乎可以获得的所有赔偿,仅占损失总额的一小部分,而且乔迪及其聘请的专家也认为,根据她与约翰所签署的这份67.3万美元的保单,这笔赔偿额也只是其中的一小部分。她在农场的住所依然破败不堪,日晒雨淋,仅得到了不到29,663.13美元的赔偿款。目前,一家人依然居住在Periwinkle Place Manor庄园,而庄园的周围则是一片狼藉。

乔迪说:“我们曾经以为自己买了很不错的保险,而且很多年来都是如此。今年的日子不好过,我们也已经向这家保险公司交了20多年的保费,而且从未出过险,但它却彻彻底底地背弃了我们,在我看来,这种行为就是犯罪。”

去年,我偶然看到了一位家族朋友代表菲利普夫妇在GoFundMe的网页上发布的信息后,才开始与乔迪接触。当时,我在撰写一篇报道,内容是我的家乡艾奥瓦州是如何应对德雷科和新冠疫情这一双重灾害。由于约翰刚刚出院,我本以为这对夫妻与新冠肺炎的斗争将成为我们讨论的主题,然而即便约翰依然在忍受着新冠肺炎后遗症的折磨,但很明显,乔迪所面临的最大压力在于,其农场当前局面让她感到异常的无助。

当我们在3月再次交谈时,事情仍然没有什么进展。6月依然是如此,不过,处于绝望边缘的乔迪希望引起外界对其困境的关注(一位邻近城镇的汽车经销商便成功地采用了这一策略),她用360美元定制了亮橙色条幅,然后将其张贴在自家沿高速公路修建的篱笆上。这些条幅上印着三个标语,控诉了本顿互助保险协会(Benton Mutual Insurance Association)以及负责理赔的第三方管理公司NCP Group在此事上的处理方式给她造成的不幸。这些条幅如今已经被摘了下来。

作为对菲利普一家控诉的回应,本顿互助称自己无法对单个索赔案例进行评论,NCP Group亦称自己无权进行评论,因为它只是第三方理赔管理机构,并不是菲利普一家的承保人。

漫长的恢复之旅

在艾奥瓦州,像菲利普夫妇这样依然在努力解决风暴灾害索赔问题的艾奥瓦人还有成千上万,而行政赔偿流程通常只是房屋所有者回归正轨需要做的首项工作。他们还在与时间赛跑,因为在这个将自己标榜为美国新保险之都的艾奥瓦州,大多数保单理赔起诉的诉讼时效仅有一年的时间。一些人称,尽管诉讼成本高昂,但这是消费者与承保人发生纠纷时唯一的求助途径。

今年,艾奥瓦州的恢复进程因为全球新冠疫情、一系列自然灾害和疫情导致的物资短缺而放缓,而且还变得更加复杂。乔迪和众多艾奥瓦人不得不应对恢复过程中的重重官僚主义障碍,这些压力给他们造成了第二次创伤。

但这个故事讲述的不仅仅是一对夫妻的艰辛,或是与某家保险公司打交道时出现的一次不愉快经历,亦或是一次恐怖的自然灾害之后混乱不堪的状况。德雷科,连同那些受损的房屋以及被掀翻的屋顶,暴露了整个保险行业存在的根本性问题。随着气候变化和导致银行资源枯竭的灾难给保险行业赖以生存的商业模式带来前所未有的压力,一些人认为保险行业已经变得越发不利于房屋所有者,而且无法提供普通人认为他们理应提供的保障。

灾害过后出现的类似纠纷并不是什么新问题。受委屈的投保人正是罗格斯大学(Rutgers University)的法学教授杰•费恩曼《拖延,推卸,辩解》(Delay, Deny, Defend)一书的主角。该书认为,一些财险企业为了提振其利润(根据管理层咨询师制定的手册),制定了多种策略来削弱人们的意志、情感能量和必要的资金,从而使其难以从承保人那里获取理所应当的赔偿。费恩曼对我说:“对于有效的索赔,现在获得赔付的难度要高于25年之前。”

飓风“桑迪”(Hurricane Sandy)对道格拉斯•奎恩在水滨区的房产造成了严重破坏,在遭遇上述令人沮丧的不公平待遇之后,当时从事金融顾问工作的他成立了美国投保人协会(American Policyholder Association),旨在阻止保险行业的欺诈行为。他说,这些斗争中的权力动态严重偏向了有着万亿美元规模的保险行业。奎恩说:“这是风暴后的风暴,而且在我看来,真正的狠角色并非是自然界的风暴。”他还表示,从险企使用老套的威吓策略到尝试通过在其Xactimate软件(保险理算员用其来给理赔定价)上刻意录入较低的实际价格来欺骗投保人,自己遭遇过的这些套路正在艾奥瓦州上演,更不用说那些曾经遭遇过自然灾害的其他地区。奎恩说:“全美各地都能够看到这样的事情。”

从其涉及的范围来看,保险行业对这类控诉根本不屑一顾,并将之视为原告律师的自私行为,而且通常根源在于消费者在灾害来临之前并没有完全理解其保单条款。作为对本人疾呼的回应,各大险企强调自己是本着关爱的态度来处理索赔,并兑现其保单中承保事项的承诺。保险信息研究所(Information Insurance Institute)也鼓励人们通过询问问题和认真筛选,去了解保单中的具体内容;该机构还警告,即便选择最便宜的保单,也要认真阅读其承保范围。保险信息研究所的媒体关系总监斯科特•霍尔曼对我说:“不要试图买辆破车,还奢望在理赔后可以换一辆凯迪拉克(Cadillac)。”

NCP Group的副总裁大卫•斯特灵在评论纠纷时笼统地说:“作为理算师,我们在这个非常脆弱、紧张、恐怖的时期参与处理投保人的理赔事宜,其中很多人以前从未提出过索赔。NCP Group希望我们协助的所有投保人都能够获得其保单允许的全部赔偿额。有时候,理赔需要进行进一步的调查;有时候需要进行额外的勘验;甚至有时候还需要进行额外的讨论。这些举措会给投保人带来更大的失望感,然而,我们将尽自身所能,尽快地妥善做好理赔工作……在应对投保人方面,最大的一个问题在于他们会期待保险公司支付保单之外的赔偿。NCP Group的委托方要求我们在给客户做出任何推荐时必须遵守保单条款。我们将付出更多的努力,来确保不会出现任何遗漏,但我们无法更改投保人的保单条款。”

不管怎么样,气候变化和不断增加的极端天气频率意味着保险公司与投保人之间的纷争只会变得更加频繁和激烈(更不用说与之相关的成本,以及各有关方面在面对新现实时的不知所措),而且越来越多的人有可能会得不到保险保障的保护。

当然,有关气候风险破坏性的证据已经是异常明了。美国国家海洋和大气管理局(National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)的数据显示,2020年,美国遭受的破坏性天气和气候灾害创下了历史纪录,损失超过10亿美元的事件共有22起,“打破了之前16起的年度纪录”。2020年因为此类事件而引发的投保人损失达到了730亿美元,较过去20年的平均值高出82%(扣除通胀因素)。

霍尔曼在写给《财富》杂志的电子邮件中称:“我们看到,因为自然灾害而引发的投保人损失的增速已经达到了警戒水平,自20世纪80年代以来增长了近700%。”邮件还指出,去年发生了创纪录的亚特兰大飓风和西部山火季(在加利福尼亚州史上最大的六场山火中,有五场就发生在去年)。“然而,保险行业在这些极具破坏力的事件中展现了领导力,向投保人支付了赔偿。”

他注意到,尽管保险公司数年前便已经将气候风险融入其业务模型,但“2020年展现了这种破坏性事件的发展态势。”

事实证明,2021年也是一个多灾之年。截至7月9日,根据美国国家海洋和大气管理局的统计,美国今年已经出现了8起损失10亿美元的天气和气候灾害。除了经济损失之外,这些灾害还造成了至少331人死亡,其中包括此前无法想象的灾害,例如得克萨斯州长达10日、造成巨大破坏的冬季冻灾,以及太平洋西北岸创纪录的热浪。

德雷科的破坏力亦超出了人们的想象,去年8月数小时内就给美国中西部地区造成了约115亿美元的损失,其对艾奥瓦东部的破坏尤为严重,在那里,高强度风力所导致的破坏远超天气预报员或保险精算师的想象。在这个有着近25.8万人口的锡达拉皮兹,几乎所有的家庭都因为风暴而出现了一定程度的损失。在酷热的8月,很多人失去电力长达一周的时间,还有些人停电远超一周。全球职业服务公司怡安(Aon)的灾害洞见业务负责人史蒂夫•博文说:“德雷科真的是让很多人大开眼界,原来雷暴也可以带来飓风级别的损失。”他表示,该地区的不动产,不管是全新的还是数十年前的老建筑,在修建时都没有考虑过这种级别的风速。博文称:“它在提醒人们,即便在过去不大会被看作能够造成重大破坏的危险如今正在越发成为一种更高级别的风险。这场风灾让众多人感到措手不及。”

确实,艾奥瓦州并没有为这种飓风级别的灾害损失做好准备。与发生野火的乡村以及飓风经常光顾的沿海各州相比,艾奥瓦人在大规模自然灾害面前相对来说缺乏经验,而且长期以来,有着丰富实战经验的美国各州在应对此类灾害时已经积累了有力的基础设施和专长,而这正是艾奥瓦州的短板。艾奥瓦州对保险理算员没有许可要求,意味着任何人都可以从事为险企评估损失的工作。

寻求帮助

同时,支持投保人索赔,或与保险公司发生争议时的资源很少。要从事公共理算或作为投保人(而不是保险人)的独立辩护人,确实需要许可证,而且艾奥瓦州提供服务的人相对较少(佛罗里达则有数千人)。同样,专门研究灾害相关保险损失的律师也寥寥无几。在非营利组织United Policyholders的网站上,艾奥瓦州的“寻求帮助”资源页面只列出了一家公共理算师机构——斯威夫特公共理算师公司(Swift Public Adjusters)和一家律师事务所——拉鲁律师事务所(Larew Law Office),资源页的列表均由赞助商提供。

詹姆斯•拉鲁曾经于2007年至2011年期间担任艾奥瓦州州长切特•卡尔弗的法律总顾问,他发现很多人不会跟财产保险公司和意外伤害保险公司打交道,又无处求助(他们经常希望找州长反映问题),2011年他开始支持投保人。拉鲁在艾奥瓦州出生长大,他表示当地人倾向于自行承担责任,也就是说在赔付问题方面不太可能挑战保险公司。他和其他人认为,即便真去挑战,州政府也不愿意面对,因为法律和政策倾向行业(举例来说,即便打赢官司,艾奥瓦州人也必须自行支付法律费用。州政府允许保险公司在合同中注明时效期限,最短只有一年,而州内书面合同常见时效为10年。)

此外,房屋受灾的人们处境本就艰难,诉讼又耗时费力。拉鲁说,保险公司知道自己被起诉的风险很低,所以才敢向投保人支付较低的费用还不担心后果。

7月底我与艾奥瓦州保险部(Iowa Insurance Division)的专员道格•奥门交谈时,保险公司已经为本州22.5万起与德雷科有关的索赔支付了30多亿美元。未决索赔约18000起,占总数8%。奥门说,从这一数量可以看出损失的规模以及劳动力和材料多么短缺。艾奥瓦州保险部已经收到392起与德雷科有关的投诉,其中大部分已经由该机构调查并结案。相关投诉中,110起被证实主要是由于“索赔过程延误以及财产核查过程中的损失”,结果是向该州投保人多支付了30.7万美元。收到《财富》杂志的询问后,艾奥瓦州保险部还发布了一份公告,建议保险公司考虑保险理算员紧缺等拖累很多人恢复的各种情况,接受延期的请求。至少有一位公共理算公司表示,多数情况下保险公司会继续拒绝延期。奥门表示,办公室正在调查德雷科导致的问题,比如允许保险条款限期一年是否合理。

常见创伤

灾难来临时,房主保险应该是好事。保险信息研究所的数据显示,20世纪50年代房主保险开始商业化,用来避免家庭受到火灾和龙卷风等改变生活且破坏财富事件的影响,很快抵押贷款机构将之列入要求,如今93%的美国房主都购买了保险。虽然标准家庭保险并不涵盖地震和洪水等灾难性事件,但通常涵盖风灾造成的损失,意味着私人保险公司应该为多数艾奥瓦州的房主因为德雷科而遭受的损失负责。

1月,艾奥瓦州国土安全和应急管理部(Iowa Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management)的恢复司司长丹尼斯•哈珀告诉我,正因如此,本州才可以迅速恢复。“[私人保险公司]能够立刻介入并提供资金。”他告诉我,此举帮助房主启动维修和恢复过程。虽然由于新冠疫情蔓延,还有德雷科导致的大范围停电,相关工作有些复杂,但对多数人来说,复苏的道路相对清晰,资金充足(哈珀解释说,相比之下,艾奥瓦州偶尔遭逢洪灾影响时,60%到70%的受影响者往往损失险覆盖不足,甚至没有保险。)

事实上,很多艾奥瓦州人在风暴过后生活比较顺利。例如,我的父母住在锡达拉皮兹,在保险公司拒赔而承包商挑战成功后,获得了新屋顶,他们觉得待遇还算公平。1月跟当地人和官员交谈后,我感受到强大的保险保障和艾奥瓦州融洽的邻里关系(人们手持电锯帮助邻居),受德雷科影响的社区做得相当好,或者至少在逐渐推进,只是由于破坏规模太大,恢复的过程漫长而艰难。

但随着时间推移,很明显我了解到的情况并不够全面。有很多像乔迪一样的房主,尽管付出了相当大的努力,还是发现自己困在过程中,保险公司的服务很差,然而保险公司至少理论上应该提供保障。有些案件涉及我的朋友和家人;还有很多像SOS求救信号一样发表在Facebook页面上,例如艾奥瓦州德雷科风暴资源页面(Iowa Derecho Storm Resource Page)和艾奥瓦州保险索赔问答页面(Iowa Insurance Claim Q&A),风暴后各种类似页面形成了支持网络。两个群组都有数千名成员,除了正常交流,也跟美国州立农业保险(State Farm)、好事达(Allstate)、本顿互助、NCP Group和其他很多保险公司交换协议信息。当时很多人感到愤怒。在跟一些人交谈中,我了解到人们的经历各有各的复杂之处,但有共同的创伤:一种无力感,一种被大肆自称好邻居的行业背叛的感觉。人们感觉被困在保险公司制造的迷宫中。

在锡达拉皮兹,德雷科将树木连根拔起。2020年8月13日,图中的树砸进一幢房子里。

52岁的宝洁(Procter & Gamble)员工丽贝卡•约德就是个例子,她和丈夫住在锡达拉皮兹,表示自己的经历是“彻头彻尾的噩梦”。为了财产索赔,她不得不跟五位现场理算员和好事达的很多内部理算员打交道,人数多到“数不清”。她的感觉是,理算员们根本没有相互交流,也没有人利用她提供的丰富文件,包括150张照片和一份详细的损坏清单。整个过程中,她感到“被忽视、被欺骗、只感觉自己很愚蠢”。她表示,屋顶还在漏水需要更换,但好事达只同意修补(她说,到访五名理算员中没有一人真正登上屋顶认真检查。)同时,好事达同意更换屋顶之前,承包商不愿意给她报价。即便后来她找到了愿意报价的承包商,但最终还是被放了鸽子,雇佣的油漆工和公共理算师也不见了(我了解到,对受德雷科影响的房主来说,相关人员突然消失是常见的问题)。刚开始,好事达为这对夫妇支付了略高于1万美元的赔偿金;经过不懈跟进,约德在一位公共理算师的帮助下收到了2万多美元,还是不到公共理算师估算金额的一半。

“情绪上的影响非常大。”她在给我的信中说。“先是让我们满怀希望,为了会面和电话打乱日程安排,很不方便。最后有些工作都是自己做的,因为自己掏腰包雇不起人,实在令人沮丧。”约德还在盼着好事达可以帮忙修房顶。整修完成之前,很难想象未来。“现在,我们身陷困境。”

在一份电子邮件声明中,好事达表示已经根据客户索赔“及时全额赔付”,并且“正积极努力解决余下异议,彻底调查所有未决索赔,以确保准确及时地赔偿客户。”该公司指出,已经解决了艾奥瓦州98%与德雷科相关索赔,为客户提供的损失补偿超过1.2亿美元。

玛丽•汉考克位于锡达拉皮兹东南部的家中,风暴将一棵树砸在了她的房上,导致车库和住所受损,比起多数人,她对自己驾驭局势的能力信心更足。作为房地产经纪人,她非常了解保单的细节和繁琐的索赔流程。但近一年后,她惊讶地发现处境与约德相似,车库仍然无法正常使用,屋顶需要维修。一下大雨,水就会渗到家里,导致破坏情况更严重。收到1.2万美元赔付款后,她和丈夫感觉相当不容易,因为第一位理算员告诉她,财产并没有问题;第二位探访后支付了4000美元,还是也远低于她认为根据保单应得的金额。“我们不在佛罗里达。”她说,对眼前情况还是有点惊讶。“多年来一直在收保费,(现在)支出却很少。”

汉考克来自西非的多哥,她认为歧视导致自家斗争更加艰难,于是她专门聘请了一位公共理算师,她注意到自己帮助过的移民家庭也有类似做法。至于她自己的战斗,几乎要认输。“我没有精力去对抗结构非常完善(且对保险公司有利)的体系。”7月底她告诉我,并补充说她和丈夫计划为房子再筹集资金,用来填补保险赔偿金不覆盖的部分。

约翰和乔迪的故事是另外一个具体而复杂的案例。两人损失和处境都很极端,但据处理过德雷科案件的人说,两人与保险公司的斗争方式跟其他人差不多。20多年来,约翰和乔迪通过本顿互助保险协会(Benton Mutual Insurance Association)购买了认为价值100万美元的房主保险,该协会1872年就已经成立,是众多服务于艾奥瓦州农村社区的农场小型互助社之一。协会总部位于艾奥瓦州基斯顿,在范霍恩西面10英里,为艾奥瓦东部19个县提供家庭和农场保险。德雷科当天,超过一半的投保人受到影响。像许多房主一样,约翰和乔迪对保险没有太多考虑,刚开始保险通过附近另一个城镇文顿的代理商购买,并且每年续保。保单的年保费为1718.30美元,涵盖了夫妇的住宅、车库、骑马场和个人财产。

2021年1月,艾奥瓦州本顿县范霍恩附近菲利普农场的约翰•菲利普。他身后的玉米垛是去年德雷科风暴中受损的房屋之一。

夫妇从未提出过索赔,因此在德雷科发生后乔迪惊讶地发现实际上有一份价值67.3万美元的保单,但对屋顶附有限制性说明,声明本顿互助“不支付风暴或冰雹造成的屋顶损失,除非进行了可接受的维修或安装了新屋顶。”《财富》杂志看到关于屋顶的说明日期为2017年8月,约翰•菲利普的名字已经印上,还有保险代理人的签名,写着“上午10点18分通话确认。”约翰和乔迪都对跟代理人就相关说明谈话毫无印象,更别提同意。(多次评论请求均未获保险代理人回应;本顿互助也拒绝对个人索赔发表评论。)

菲利普聘请的公共理算师和律师表示,该合同是纠纷的关键,因为本顿互助认为,已经免除了对屋顶损坏或房屋内因为屋顶受损而影响物品的赔偿责任。这也反映了律师、United Policyholders的执行董事艾米•巴赫称之为保险业“有问题”的趋势,即悄悄修改房主的保单。United Policyholders是非营利组织,1991年成立,艾米•巴赫是该机构的联合创始人。

“由于与气候变化相关的风暴和水灾事件越来越多,保险公司越发积极限制屋顶损坏和屋顶维修费用。”她解释说,这一做法开始于2013年左右。“这一问题在艾奥瓦州引起广泛关注,因为类似德雷科的情况下,既涉及风暴又涉及大雨。”

巴赫说,调整通常不会与投保人明确沟通,而且实施得太迅速,房主和监管机构都跟不上。条款调整实际上降低了房主保单的价值,成本却很少降低(奥门说,这是艾奥瓦州保险部根据德雷科正在研究的另一问题。)2020年巴赫的组织发起了一项全国性倡议,即重建保险安全网联盟(Restoring the Insurance Safety Net Coalition),希望呼吁监管机构、官员和法院意识该问题并制定标准,防止保险公司过分缩小范围。毕竟,如果房子没有屋顶,那价值何在?

根据NCP Group(总部位于佛罗里达州,本顿互助委托该公司评定和处理索赔工作)编写的报告,菲利普夫妇发现其实价值很少。保险公司认定三层农舍赔偿金或实际现金价值仅为16786.17美元。“简直滑稽。”乔迪告诉我。“他们愿意(赔的钱)只够给天花板塌着的屋子刷刷墙。”尽管进行了上诉,也有乔迪聘请的公共理算师的帮助(理算员评估保险赔偿金超过67.3万美元的保单),但据乔迪和代理人所知,NCP Group并未另派理算员重新核查。第一位理算员已经不在NCP工作。(NCP不评论个人索赔。)

公共理算师为该房产争取了几笔额外赔付,但与巨额估算相差甚远。种种努力停滞不前时,乔迪与公共理算师的关系也迅速恶化,而双方合作曾经是给了他们巨大的希望。她从公司也得不到答案。

和我采访的其他人一样,乔迪让我感觉到,理赔过程中最令人不安的部分是缺乏人性:个人遭受巨大损失和创伤时,可依赖的人不回电话也不回短信;沟通也很差,甚至无法沟通;理算员、承包商或公共理算师会突然消失,有时还会被随意换人重新走流程。大灾难之后似乎都是此种模式,就像这一次,然而明明时间和资源都很匮乏。

就在此时,乔迪返回Facebook上的一个德雷科群组,找到了年轻而精力充沛的律师格雷格•厄舍,厄舍在锡达拉皮兹地区长大,后来从事财产和伤亡索赔。到2021年年初,他每周都要接8到10个求助电话,每晚等到年幼的儿子上床睡觉后仍然要工作。回顾诸多问题后,他得出了令人沮丧的结论:“几乎每个人情况都很糟。”6月初,当我们谈起过去一年时,他显得筋疲力尽又很愤怒,他滔滔不绝讲述了大保险公司糟糕的做法,还有遇到令人不安的事。他有一位名叫贝基•哈德森的客户,房子被压在树下,经营家庭日托中心的地下室也被污水淹没。她跟好事达的多位理算员打过交道,其中一人建议她好好清理,而不是更换污水泡过的日托用品。厄舍认为,好事达少赔了她至少10万美元。(好事达表示,已经迅速支付了索赔中无争议的损失,并且“所有未决索赔都经过彻底调查,以确保客户及时准确收到赔款。”)

现在他通过评估指导菲利普一案,走的纠纷解决流程,虽然并非没有风险,但比诉讼更快成本也更低。他说,准备在对菲利普家的财产联合检查时,与本顿互助的律师积极沟通下。虽然乔迪的案子离解决还有点远,但现在由于厄舍介入,感觉有些希望。而她描述的悲惨篇章,也是“最糟糕的一年”,似乎慢慢走向尾声。最近几周,乔迪获得了切尔西市议会的批准,骆驼克林格和驯鹿搬到了Periwinkle Place Manor庄园。她正在整修房子,方便夫妇二人搬回去,又开始主持谋杀悬疑剧院活动。她开始接受可能再也不会住在农场,只是努力记住,除了保险大战和过去一年的困境,前方还有未来。(财富中文网)

译者:冯丰

审校:夏林

A grant from the NIHCM Foundation helped fund reporting for this story.

Even against the backdrop of the past 18 months, and epic levels of American suffering, John and Jodi Philipp have had a rough go.

They both struggle with serious health issues—she a brain tumor, and he Stage 4 cancer that was diagnosed in November 2019 after experiencing a couple of strokes. As the pandemic began in early 2020, their rural Iowa businesses—2 Jo’s Farm and Periwinkle Place Manor—took a hit, since both depend on visitors and gathering for events. Then, on Aug. 10, as Jodi was driving John home from a cancer treatment at the University of Iowa to their farm in Van Horne, a town of 900-some people, they were caught in a freakishly intense windstorm—a derecho, or straight-line wind event—that wreaked havoc that day on a 770-mile swath across the Midwest and would go down in the books as the most expensive thunderstorm in history.

They pulled over, but as the torrential rain and hurricane-force wind blasts—gusts peaked at 140 mph—rattled their car, “we felt like we were going to die,” said Jodi, who was receiving a stream of texts and calls from her son at the farm until his signal went dead. His last message to her was that they should “be prepared.”

The drive, normally 50 minutes, took hours. As they passed silos that had blown onto the highway, and barns and crops that had toppled to the ground, they took in what seemed like a full preview of the storm’s destruction.

Even so, what Jodi found at the farm, a 13-acre property off Highway 30 (the old Lincoln Highway) in Iowa’s rural Benton County, left her dazed.

The Philipps’ farm is not a traditional Iowa farm. The couple, who for decades have played Santa and Mrs. Claus at venues and holiday parties around the Midwest, raise reindeer and have a camel named Kringle. The property, which hosted events, also had a mini Western town and a riding arena. Their farm buildings were demolished. Most of the trees were down, and the house and garage had too much damage to quickly process. The place was uninhabitable, she says, and most of their personal belongings damaged beyond repair. “It’s still unbelievable,” she told me when I first spoke with her. “When we go there, we just walk around and stare and wonder, what are we going to do?”

That conversation was in early January, when Jodi was making trips to Van Horne two times a day to feed and water the animals. She and John were living 30 minutes away, at their other business, Periwinkle Place Manor, a former funeral home that they bought and restored several years ago before converting it into a bed-and-breakfast (or dead-and-breakfast, as Jodi winkingly markets it) that hosts murder-mystery theater.

The manor, a Victorian mansion that dates to the late 1800s, is in Chelsea, Iowa, a low-lying, flood-prone town of 300 residents on the other side of the Lincoln Highway (so flood-prone that the city council voted to move Chelsea to higher ground decades ago; it hasn’t). Chelsea got crushed by the derecho, too—its town library was a casualty—but the manor sustained only minor damage (though it did lose power for 2.5 months), and that’s where the couple were staying with their intellectually disabled 26-year-old daughter and dog when both John, 72, and Jodi, 62, came down with COVID in late November. Jodi recovered quickly enough to take on a few Mrs. Claus jobs in December, but John, who had blood clots in his lungs and pneumonia, was in the hospital for a month. For the third time in a year, Jodi thought John was going to die. He came home on Christmas Eve day.

Yet, for the almost boundless trauma the Philipps faced in 2020, Jodi would argue that this year hasn’t gotten better. In the aftermath of these events, and the effort to recover, things have only gotten worse.

That’s largely because of a battle with her property insurer, which by Jodi's telling has been a frustrating, confusing, lonely, and increasingly desperate months long slog. To date, their insurer has paid out $212,525.43 for derecho-related claims to the property—almost all of it for the demolished riding arena—a small fraction of the total cost of the damages and of the sum that Jodi and experts she has hired argue she and John are owed under their $673,000 policy. Her home, on which the insurer has paid out just $29,663.13, remains in tatters and exposed to the elements. The family remains living at Periwinkle Place Manor, in an austere limbo.

“We have good insurance, or we thought we did, for many, many years,” said Jodi. “It’s been a rough year, and for the insurance company to completely turn their back on you after you’ve paid for insurance for 20 some years and never had a claim—in my opinion that should be a crime.”

I had initially gotten in touch with Jodi when I came across a GoFundMe page that a family friend had made on their behalf last year. At the time, I was reporting a story about how my home state was coping with its dual disasters—the derecho and the pandemic. With John just out of the hospital, I had assumed the couple’s battle with COVID would dominate our discussion, but even as John struggled with the lingering effects of the virus, it was clear the source of greatest stress for Jodi was the utter helplessness she felt about the situation around her farm.

When we spoke again in March, there had been little progress. It was the same story in June, though Jodi, at a breaking point and hoping to call attention to her plight (a car dealership in a neighboring town had successfully deployed the strategy), had custom-ordered for $360 bright orange banners, which she then tacked up to their fence that runs along the highway. The banners, which are no longer displayed, trumpeted out over three 10-foot-long signs the distress she felt due to the treatment by her insurer Benton Mutual and NCP Group, the third-party administrator working on the claim.

In response to the Philipps’ allegations, Benton Mutual said it could not comment on individual claims, as did NCP Group, which as a third-party claims administrator, and not the Philipps’ insurer, noted that it did not have authority to do so.

The long road to recovery

The Philipps are among thousands of Iowans still struggling to resolve claims related to the storm, an administrative task that is often just the first step for homeowners trying to get back on track. They’re also up against the clock: In Iowa, a state that promotes itself as the nation’s new insurance capital, most policyholders have just one year before the statute of limitations runs out for filing suit over claims—the only recourse (albeit an expensive one), some argue, that consumers have in disputes with their insurers.

In a year when the recovery process in Iowa has been slowed and complicated by a global pandemic and a slew of natural disaster and pandemic-induced shortages, those pressures add to what many, including Jodi, describe as a second trauma: navigating the red-tape-ridden obstacle course to recovery.

But this story is about more than one couple’s travails, or one bad experience with an insurance company, or even the messy aftermath of a single horrible natural disaster. The derecho, along with damaging homes and blowing the roofs off buildings, exposed the fundamental problems of an entire industry. As the business model that undergirds the insurance sector faces ever more pressure from climate change and bank-breaking catastrophes, some argue that it has become increasingly stacked against homeowners and fails to provide the safety net that ordinary people believe they have paid for.

Such battles in the wake of disaster are hardly a new problem. The story of wronged policyholders is the animating force behind Delay, Deny, Defend, the 2010 book by Rutgers law professor Jay Feinman. The book argues that some property and casualty insurers, in an effort to boost their bottom lines (following a playbook developed by management consultants), have developed tactics to sap people of the will, emotional energy, and financial wherewithal it takes to collect what they’re rightfully owed by their insurers. “It’s much more difficult to get paid for a valid claim now than it was 25 years ago,” Feinman told me.

The frustration and injustice of that experience is what led Douglas Quinn, a then-financial adviser whose waterfront home was badly damaged by Hurricane Sandy, to found the American Policyholder Association, an organization aimed at stopping fraud in the sector. The power dynamic in these battles is heavily tilted in favor of the multibillion-dollar insurance industry, he said. “It’s the storm after the storm, and in my experience the storm was the easy part,” said Quinn, who added he’s seen the same patterns he experienced—from insurers using age-old intimidation tactics to trying to shortchange policyholders by swapping in artificially low material prices on their Xactimate software (which adjusters use to price claims)—play out in Iowa, not to mention every other place where there’s been a natural disaster. “We see these things all over the country,” said Quinn.

The industry, to the extent that it engages, is dismissive of such characterizations, which it sees as self-serving messaging of plaintiffs’ attorneys, and often the result of consumers not fully understanding their policies before disaster strikes. In response to my outreach, companies emphasized their commitment to handling claims with care and honoring the coverage they set out in their policies. The Information Insurance Institute (III) also encourages people to know exactly what’s in those policies by asking questions and shopping carefully; it cautions people against choosing the cheapest policies without scrutinizing the coverage provided. “Don’t buy a junk car and then expect a Cadillac of a product when you have a claim,” III Media Relations director Scott Holeman told me.

Dave V. String, a vice president at NCP Group, the administrator that processed the Philipps' claim, commented generally on disputes: “We as adjusters are involved in handling claims in very tenuous, stressful and scary times for insureds, many of whom have never filed a claim before. NCP Group wants every insured we assist to be paid every dollar their policy allows. Sometimes this takes further investigations; sometimes it takes additional inspections; and sometimes it takes additional discussions. These add to insureds’ frustrations, but we do everything we can to get it right as quickly as possible…One of the largest obstacles to overcome with insureds is when they expect coverage for something their policy does not provide. NCP Group’s clients require that we follow the language of the policy in any recommendations we make to our clients. We will go out of our way to make sure nothing is missed, but we cannot change the terms of an insured’s contract.”

Regardless, climate change and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events—not to mention the mounting costs associated with them, and the underpreparedness of all involved for this new reality—suggest these battles between insurers and policyholders will only become more frequent and bruising, with a growing number of people likely to fall through their insurance safety net.

Evidence of those forces, of course, is already in plain view. The U.S. faced a record number of devastating and costly weather and climate disasters during 2020—a total of 22 events in which losses exceeded $1 billion—according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA. The government agency noted last year’s count “shattered the previous annual record,” which involved 16 such events. Insured losses due to those events in 2020 stand at $73 billion, 82% above the (inflation-adjusted) average figure for the past 20 years.

“We’ve witnessed insured losses caused by natural disasters increasing at an alarming rate, growing nearly 700% since the 1980s,” Holeman wrote in an email to Fortune, adding that last year brought record-breaking Atlantic hurricane and Western wildfire seasons (which included five of California’s six largest ever wildfires). “Still, the insurance industry has demonstrated leadership through disruption, paying claims for the insured.”

He noted that while insurers have built climate risk into their business models for years, “2020 illustrated how the disruption continuum is evolving.”

And 2021 is proving to be disruptive too. As of July 9, NOAA had tallied eight $1 billion weather and climate disasters in the U.S. this year, which, beyond economic losses, resulted in the deaths of at least 331 people. They include events that were previously simply unfathomable, like Texas’s crippling 10-day winter freeze and the Pacific Northwest’s record-shattering heat wave.

The derecho, too, outdid the imagination, racking up in a matter of hours last August an estimated $11.5 billion in damage across the Midwest. The devastation was particularly severe in eastern Iowa, where the intensity of the wind led to destruction well beyond what weather forecasters or actuaries ever thought possible. Just about every home in Cedar Rapids—a metropolitan area of nearly 258,000 people—sustained some sort of damage in the storm. Many people in the very hot month of August lost power for more than a week, and some for far longer. “The derecho really opened a lot of eyes in terms of the fact that thunderstorms can end up leading to hurricane levels of losses,” said Steve Bowen, head of catastrophe insight for Aon, the global professional services firm. He noted that properties in the region, whether brand new or decades old, weren’t built to withstand such wind speeds. “It was a reminder that even perils that historically haven't necessarily been massive drivers of damage are increasingly becoming higher risk,” added Bowen. “This is an event that caught a lot of us off guard.”

Indeed, Iowa was not ready for hurricane level losses. Compared to wildfire country, and hurricane-prone coastal states, Iowans are relatively inexperienced when it comes to widespread natural disasters, and Iowa lacks the robust infrastructure and know-how that more practiced states have developed over time to deal with such events. The state has no licensing requirements for insurance adjusters, meaning just about anyone can do the job of assessing damage for insurers.

Finding help

Meanwhile, resources to support insureds with the claims process or in disputes with their insurers are few. Public adjusting, or working as an independent advocate for policyholders (rather than for insurers), does require a license, and there are a relatively small number of them providing the service in the state. (They number in the thousands in Florida.) Similarly, lawyers who specialize in disaster-related insurance losses are extremely few. On the website of United Policyholders, a nonprofit that aims “to level the playing field between insurers and insureds,” the Iowa “Find Help” resource page lists just one public adjuster, Swift Public Adjusters, and one law firm, Larew Law Office. (The listings are sponsored.)

James Larew, who served as general counsel to Iowa Gov. Chet Culver from 2007 to 2011, started his practice to support policyholders in 2011 after realizing there were many people in the state who had issues with property and casualty insurers and nowhere to turn (they often tried to meet with the governor about their problems). Born and raised in the state, Larew noted that Iowans tend to take their lumps, meaning they’re culturally unlikely to challenge their insurers over claim payments. Even when they do, the state is not hospitable to such challenges because of laws and policies that bend in favor of the industry, he and others contend. (Iowans have to pay their own legal fees, even if they do win, for example, and the state allows insurers to write into their contract a limitations period as short as one year, compared to the 10-year statute of limitations that is presumed for written contacts more broadly in the state.)

Add to that the vulnerable circumstances of people whose homes have been been stricken by disaster, and the fact that lawsuits are wearing and expensive. Insurance companies know the risk they will be sued is low, a dynamic that allows them to underpay policyholders with little fear of consequence, Larew said.

When I spoke to Doug Ommen, commissioner of the Iowa Insurance Division (IID), in late July, insurers had paid out more than $3 billion on 225,000 derecho-related claims in the state. Roughly 18,000, or 8% of those claims, remained open, a volume that Ommen said reflected the scale of losses as well as shortages of labor and materials. The IID had received 392 derecho-related complaints, most of which have been investigated and closed by the agency. Of those, 110 of the complaints were confirmed—largely over “delays in the claims process as well as damages missed during inspections of the property”—resulting in an additional $307,000 paid to policyholders in the state. After Fortune asked about the issue, the IID also issued a bulletin advising insurance carriers to accommodate requests for extensions given the circumstances, including a shortage of insurance adjusters, that have slowed the recovery process for many in the state; at least one public adjusting firm says, in most cases, insurers continue to deny extensions. Ommen said his office was investigating issues raised by the derecho, like whether allowing one-year limitations in policies made sense.

A common trauma

Homeowners insurance should be a blessing when disaster strikes. Commercialized in the 1950s as a product to protect families against life-altering, wealth-destroying events like fire and tornadoes, mortgage lenders soon made it a requirement, and today 93% of American homeowners have a policy, according to the Insurance Information Institute. While standard home insurance doesn’t cover all catastrophic events—see earthquakes and floods—it does generally cover wind damage, meaning that private insurers were on the hook for the majority of derecho-related losses suffered by homeowners in the state.

That helped the state bounce back quickly, Dennis Harper, recovery division administrator for the Iowa Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, told me in January. “[Private insurers] were able to get in and get checks written right away,” jump-starting the repair and recovery process for homeowners, he told me. While the pandemic and widespread power outages due to the derecho complicated the job somewhat, the path to recovery for most was relatively clear and well-funded. (By comparison, explained Harper, 60% to 70% of people affected in the state’s occasional flood events tend to be under- or uninsured against losses.)

Indeed, many Iowans had a fine experience in the aftermath of the storm. They may have had to jump through a few hoops—my parents, who live in Cedar Rapids, for example, got a new roof after their contractor successfully challenged the insurance company’s denial for one—but they feel they were treated fairly. After talking with people and officials in January, my sense was that between robust insurance protection and Iowan neighborliness (Iowans helping Iowans with chain saws), the state’s derecho-impacted communities were doing pretty well, or at least moving forward in what would necessarily be a long and arduous recovery due to the scale of damage.

But as the months have worn on, it's become clear that that's not the complete picture. There are lots of stories involving homeowners like Jodi, who despite considerable effort feel they are stuck in the process and poorly served by the insurance companies whose policies, at least in theory, were supposed to protect them. Some of these cases involved my friends and family; scores of others are posted, SOS-like, on Facebook pages—such as the Iowa Derecho Storm Resource Page and Iowa Insurance Claim Q&A—that were formed as a support network after the storm. Both of those groups have thousands of members who, among other things, exchange information on their dealings with State Farm, Allstate, Benton Mutual, NCP Group, and any number of other insurers. Many, at this point, are exasperated. Their experiences, as I’ve learned in talking with a number of them, are uniquely complicated, but they share common traumas: a feeling of powerlessness and a sense of betrayal by an industry that so prolifically advertises itself as a good neighbor. They feel trapped in a labyrinth of their insurer’s making.

Take Rebecca Yoder, a 52-year-old Procter & Gamble employee who lives in Cedar Rapids with her husband; she describes her experience as “an utter nightmare.” For her property claim, she’s had to deal with five different field adjusters and so many desk adjusters at Allstate that she’s “lost count.” She has the sense that none of them talk to each other or make use of the copious documentation—150 photos and a detailed list of damages—that she provided them. Throughout the process, she has felt “ignored, lied to, made to feel stupid.” Her roof is leaking and, she argues, in need of replacement, but Allstate has agreed only to patch it. (She said none of the five adjusters who visited actually got on her roof to properly inspect it.) Contractors, meanwhile, were unwilling to give her quotes unless Allstate approves a full roof replacement. She finally found a contractor who would, but he disappeared on her, as have a painter and a public adjuster she hired (ghosting is a common problem for derecho-impacted homeowners, I’ve learned). Initially, Allstate paid the couple a little over $10,000 for the claim; through dogged follow-up, Yoder, with the help of a public adjuster, has gotten the total to a little over $20,000—less than half of what her public adjuster estimates she is owed.

“The emotional toll of it has been very tough,” she wrote to me. “Getting our hopes up, shuffling our schedules around meetings and phone calls has been inconvenient. Doing some of the work ourselves because we can't afford to hire someone out-of-pocket is frustrating.” Yoder is holding out hope that Allstate will come around on her roof; it’ll be hard to contemplate the future until the repairs are complete. “For now, we are trapped.”

In an emailed statement, Allstate said it “promptly paid all the agreed upon amounts" from the customer’s claim and that it was “working actively to resolve any remaining differences and thoroughly investigate all open claims to ensure accurate and timely payments to our customers.” The company noted that Allstate has settled 98% of its Iowa derecho claims and provided customers over $120 million to recover from their losses.

When the derecho caused a tree to fall on Marie Hancock’s southeast Cedar Rapids home, resulting in damage to her garage and dwelling, she felt more confident than most in her ability to navigate the situation. As a realtor, she understood the fine print of policies and the tedium of the claims process. But nearly a year later, she’s surprised to be in a situation similar to Yoder’s, with her garage still not functional and her roof in need of repair. Water seeps into her home anytime it rains heavily, worsening water damage within. The $12,000 she and her husband received for their claim feels hard-won—a first adjuster told her there was nothing wrong with her property; a visit from the second yielded a payment of $4,000—but also far less than what she believes she is owed under her policy. “We’re not in Florida,” she said, still a little stunned by what she’s witnessed. “They’ve had years of collecting premiums with very little payouts [here].”

Originally from Togo, in West Africa, Hancock feels discrimination has made her family’s battle tougher—she hired a public adjuster for that reason—and she’s noticed a similar pattern with immigrant families she’s helped through the process. With her own battle, she is close to conceding. "I don't have energy to spend fighting a system that I know is very well structured [to the benefit of insurers],” she told me in late July, adding that she and her husband plan to refinance their home and use that money to fix what the insurance money hasn’t covered.

The story of John and Jodi Philipp is another specific and complicated case. Their losses and circumstances are extreme, but according to those who have dealt with derecho cases, the battle with their insurer follows the patterns of others. For more than 20 years, Jodi and John Philipp had what they thought was a $1 million homeowners insurance policy through Benton Mutual Insurance Association, which, founded in 1872, is one of many small farm mutuals that serve Iowa’s rural communities. Headquartered in Keystone, Iowa (pop. 600), 10 miles west of Van Horne, it offers home and farm insurance in a 19-county area in eastern Iowa; more than half its policyholders were affected on the day of the derecho. Like many homeowners, John and Jodi didn’t think much about their policy, which they originally purchased through an agent in Vinton, another nearby town, and renewed every year. The policy, which has an annual premium of $1,718.30, covered the couple’s home well as the garage, the riding arena, and personal property.

The couple had never filed a claim, and so in the wake of the derecho Jodi was surprised to learn she actually had a $673,000 policy with a restrictive roof endorsement stating that Benton Mutual would “not pay for loss to roofs caused by windstorm or hail until acceptable repairs have been made or a new roof is installed.” The roof endorsement, which Fortune has seen, is dated August 2017, and John Philipp’s name had been printed in for a signature by an insurance agent, with the note “by phone 10:18 a.m.” Neither John nor Jodi remembers a conversation with an agent about the endorsement, or ever agreeing to it. (The insurance agent did not respond to multiple requests for comment; Benton Mutual declined comment on individual claims.)

That piece of paper is key to the Philipps’ dispute, as Benton Mutual argues it absolves it from covering roof damage or anything inside the house that was damaged because of a faulty roof, according to the public adjuster and attorney hired by the Philipps. It also reflects what Amy Bach, an attorney and the executive director of United Policyholders, the nonprofit she cofounded in 1991, calls a “problematic” trend in the insurance industry: the quiet modification of homeowners’ insurance policies.

“Because of the increasing number of wind and water events associated with climate change, insurers have gotten more and more aggressive in limiting what they pay for roof damage and roof repairs,” she explained, dating the start of the practice to around 2013. “That’s a problem that’s come home to roost in Iowa, and in a situation like the derecho because it involved wind and rain.”

Bach said such changes, which reduce the value of homeowners policies but rarely the cost of them, are usually not communicated clearly to policyholders, and have been implemented too quickly for homeowners and regulators to keep up. (Ommen said this is another issue the IID is examining in light of the derecho.) Bach’s organization launched a national initiative, Restoring the Insurance Safety Net Coalition, in 2020 to bring to regulators, officials, and courts an awareness of the issue and to institute standards that prevent excessive coverage-shrinking policy rewrites. What, after all, is the value of a house with no roof?

Very little, the Philipps would discover, according to the report prepared by NCP Group, a Florida-based company that Benton Mutual had hired to adjust and process claims. The company determined covered damages, or the actual cash value of damages to their three-story farmhouse, to be $16,786.17. “It was almost comical,” Jodi told me. “They wanted to give us [a payment] to the paint the rooms in the house when the ceilings are caving in.” Despite appeals and the help of a public adjuster Jodi hired (which assessed the covered damages as exceeding their $673,000 policy), NCP Group hasn’t sent another adjuster to reinspect the place to the knowledge of Jodi or anyone representing her. The first adjuster no longer works for NCP. (NCP does not comment on individual claims.)

The public adjuster secured a few additional payments for the property, but nothing close to the firm’s huge estimates. And when those efforts stalled, Jodi’s relationship with the public adjuster—once a source of so much hope—soured. She couldn’t get answers from the firm either.

As with others I spoke with, my sense from Jodi was that the most upsetting part of this process was its lack of humanity: the fact that at a time of extraordinary personal loss and trauma, the people they depended on for help didn’t return calls or texts; that they communicated things poorly, if at all; that an adjuster or contractor or public adjuster would just up and disappear, sometimes replaced by another one, restarting the whole process, and sometimes not. It’s a pattern that seems to happen after widespread disasters, like this one, where there’s a scarcity of time and resources.

It’s at this point that Jodi returned to one of the Derecho Facebook groups, which led her to Greg Usher, a young and energetic attorney who grew up in the Cedar Rapids area and eventually found his way to property and casualty claims. By early 2021 he was getting eight or 10 calls a week and working nights after putting his young son to bed. After reviewing so many issues, he had reached the depressing conclusion: “Almost everyone’s getting screwed.” When we spoke in early June, he seemed both exhausted from the past year and freshly outraged by it, rattling through the worst practices of the major insurers and the upsetting things he had come across. There was his client Becky Hudson, whose house had been crushed under a tree and her basement—where she ran a home day care—flooded with sewage. She had dealt with multiple Allstate adjusters, including one who suggested she just clean, rather than replace, the day-care items that had been contaminated by the sewer water. Usher believes Allstate has underpaid her claim by more than $100,000. (Allstate said it had promptly paid all undisputed damages from the claim, and that “all open claims are thoroughly investigated to ensure our customers receive accurate and timely payments.”)

He’s now shepherding the Philipps’ case through appraisal, a dispute resolution process that, while not without risk, is quicker and less expensive than litigation. He says communication with Benton Mutual’s attorney has been positive as they prepare for a joint inspection of the Philipps' property. While Jodi’s case is far from resolved, she is feeling more hopeful now that it is in Usher’s hands and that this miserable chapter—“the worst frickin’ year,” as she described it—seems to be inching toward an end. In recent weeks, with Jodi having secured the Chelsea city council’s approval, Kringle and the reindeer moved to Periwinkle Place. She is fixing up a structure on the property for her and John to move into, and she has begun hosting murder-mystery events again. She is coming to accept that she will probably never again live at the farm and is instead trying to remember that beyond this insurance battle and the limbo of the past year, there is a future.