备受瞩目的《联合国气候变化框架公约》第二十六次缔约方大会(COP26)将于11月7日在格拉斯哥开幕,大会主席阿洛克·夏尔马为该为期数周的会议定下了一个首要目标:“让煤电成为历史。”

根据国际能源署(International Energy Agency)的数据,煤炭满足了全球40%的电力需求,同时造成了全球46%的碳排放量。该机构表示,为了避免气候变化造成最大的危害,各国政府需要共同努力将煤电在全球电力供应中的占比削减至1%以下。

但煤炭不会一下子就退出历史舞台。

煤炭的使用量在过去一年出现反弹,终止了2020年的下降趋势,打断了发达经济体长达数十年的使用量下降势头。煤炭的期货价格也大幅走高,在一些市场暴涨400%,创下历史新高。与此同时,美国煤炭生产商的股价已经从历史低点反弹,博地能源公司(Peabody Energy)的股价在12个月内飙涨了700%以上。

然而,煤炭需求激增和价格飙升,可能更多的是当前能源危机的表征,而不是煤炭持续复苏的苗头。围绕煤炭的长期投资正在减少,而从经济角度来看,可再生能源的竞争力则继续攀升。煤炭类股现在可能处于狂热状态,但价格飙涨只是大宗商品垂死挣扎的迹象,而不是市场复苏的迹象。

煤炭重新当道

根据国际能源署的数据,过去20年,发达经济体的煤炭使用量有所下降。在美国,国内页岩气产量激增加剧了这一趋势。天然气比煤炭便宜,燃烧时产生的碳也更少,这意味着从煤炭转向天然气,美国电力生产商就能够节省成本,同时也可以避免违反联邦政府关于碳排放的规定。

但是,随着今年夏天全球能源危机的爆发,煤炭重新成为了供电选择。

今年,受迫于天然气短缺,美国自2014年以来首次增加了煤电的使用量。在大西洋彼岸,英国结束了持续两个月的无煤发电,于9月重新启用退役的燃煤发电厂,使得煤电在英国发电量中的占比从零回升至3%。

Saxo Markets的高级市场分析师艾迪森·潘说:“我们注意到,随着天然气成本飙升,政府预计供暖需求也将达到顶峰,欧洲国家正在纷纷采购煤炭,以保障冬季能源供应。”

英国的电力危机是由北海(North Sea)异常温和的天气引发的,当地的海上风力发电通常能够满足该国25%的能源需求。随着风力停止,风能在英国能源结构中的占比降至7%。与此同时,随着欧盟逐渐摆脱新冠疫情阴霾,用电需求增长,天然气的价格在欧洲各地呈现飙涨。

但对于迫切需要天然气的欧洲能源供应商来说,不幸的是,中国也出现了类似的供需失衡。自今年5月以来,由于夏季异常干燥,水力发电减少,中国出现了周期性停电,多个制造业中心的生产线受阻。为了维持电网运行,中国电力生产商加大了天然气进口力度,推高了天然气价格。

现在,该国政府急于确保冬季供暖所需的电力,因而改变了多年来逐步消除煤矿产能过剩的政策,命令矿工“不惜一切代价”增加产量。对于已经投产的矿工来说,开采更多煤炭的成本并不是很高,而且由于煤炭价格处于历史高位,煤矿的利润率也相当可观。

但对于那些必须购买燃料的电力生产商来说,煤炭价格高不可攀,实在采购不起。

煤价疯涨

今年10月初,欧洲西北部的煤炭期货价格突破每吨275美元,短短四周内飙升63%。与此同时,纽卡斯尔煤炭——反映亚洲大宗商品价格的基准——在截至9月的12个月内飙涨了400%以上,达到每吨269美元。但随着煤炭价格疯涨,电力生产商推迟了补购这种高价大宗商品的计划。

“我认为,从经济上讲,我们已经尽可能地用尽煤炭的价值了。”能源咨询公司Lantau Group经理大卫·菲什曼说道。据国际能源署称,2020年6月,新太阳能发电装置的成本低于开设新燃煤电厂的成本,而目前煤炭价格飞涨,使得这种燃料在竞争力上更加不如可再生能源。

在发达经济体,煤矿企业已经考虑到煤炭需求下降的长期趋势,因此已经停止投资于产能扩张。根据美国能源信息署(U.S. Energy Information Administration)称,美国煤炭产量在2008年达到顶峰,去年则跌至1965年以来的最低水平。

与此同时,自2013年以来,美国能源供应商——那些烧煤而不是采煤的能源供应商——对电网的煤电产能贡献一直都没有增加。尽管今年美国煤电使用量将迎来自2014年以来的首次增长,但美国能源信息署预计,明年煤电使用量将重回下降通道。

据路透社(Reuters)报道,哪怕是在特朗普政府努力振兴美国煤炭业,废除奥巴马时代的清洁能源计划(Clean Power Plan,该计划指引能源部门减少燃煤电厂的碳排放)的时期,大多数能源生产商也仍然致力于逐步淘汰煤电。为什么呢?与可再生能源和天然气相比,煤炭成本太高。

菲什曼说:“我认为,煤炭只会变得越来越没有竞争力。”

寻找替代能源

然而,在亚洲,煤炭目前仍然占据主导地位。

燃煤发电厂为印度贡献了约70%的电力,为中国贡献了60%的电力。总体而言,亚洲在全球煤电总量中占大约80%,它也是全球煤炭增长最强劲的市场。根据亚洲气候变化投资者联盟(Asia Investor Group on Climate Change)的数据,在截至2030年的10年里,煤炭将为东南亚地区带来50%的电力增长。

除了煤炭是一种可靠且方便的能源外,印度尼西亚和澳大利亚的政府补贴、国家资助、矿业繁荣等因素也助力亚洲电力生产商将煤炭成本控制在相当可观的水平。从传统的燃煤电厂转向可再生能源电网的种种额外成本——例如关闭煤电厂、培训新技术人员和投资绿色技术——传统上也促使发展中国家的政府继续依赖煤炭。

但亚洲国家对煤炭项目的资助正在走向枯竭。今年9月,中国国家主席习近平承诺中国将停止为海外煤炭项目提供资金,这实际上切断了国际煤炭项目的最后一个公共筹资来源。此前,日本和韩国也相继承诺今年不再为煤炭项目提供融资。上周,亚洲开发银行(Asian Development Bank)宣布,计划通过收购煤电厂,让其提前停止运营,来加速煤炭在亚洲的消亡。

然而,消灭煤炭只是成功了一半。国际能源署预测,2020年至2040年间,仅东南亚地区的电力需求就将翻一番。地方政府将不得不寻找一些新的能源来源,来满足日益增长的用电需求。因此,如果《联合国气候变化框架公约》第二十六次缔约方大会想让煤炭成为历史,敦促发达国家增加对贫穷国家可再生能源项目的资助就将是一大关键。(财富中文网)

译者:万志文

备受瞩目的《联合国气候变化框架公约》第二十六次缔约方大会(COP26)将于11月7日在格拉斯哥开幕,大会主席阿洛克·夏尔马为该为期数周的会议定下了一个首要目标:“让煤电成为历史。”

根据国际能源署(International Energy Agency)的数据,煤炭满足了全球40%的电力需求,同时造成了全球46%的碳排放量。该机构表示,为了避免气候变化造成最大的危害,各国政府需要共同努力将煤电在全球电力供应中的占比削减至1%以下。

但煤炭不会一下子就退出历史舞台。

煤炭的使用量在过去一年出现反弹,终止了2020年的下降趋势,打断了发达经济体长达数十年的使用量下降势头。煤炭的期货价格也大幅走高,在一些市场暴涨400%,创下历史新高。与此同时,美国煤炭生产商的股价已经从历史低点反弹,博地能源公司(Peabody Energy)的股价在12个月内飙涨了700%以上。

然而,煤炭需求激增和价格飙升,可能更多的是当前能源危机的表征,而不是煤炭持续复苏的苗头。围绕煤炭的长期投资正在减少,而从经济角度来看,可再生能源的竞争力则继续攀升。煤炭类股现在可能处于狂热状态,但价格飙涨只是大宗商品垂死挣扎的迹象,而不是市场复苏的迹象。

煤炭重新当道

根据国际能源署的数据,过去20年,发达经济体的煤炭使用量有所下降。在美国,国内页岩气产量激增加剧了这一趋势。天然气比煤炭便宜,燃烧时产生的碳也更少,这意味着从煤炭转向天然气,美国电力生产商就能够节省成本,同时也可以避免违反联邦政府关于碳排放的规定。

但是,随着今年夏天全球能源危机的爆发,煤炭重新成为了供电选择。

今年,受迫于天然气短缺,美国自2014年以来首次增加了煤电的使用量。在大西洋彼岸,英国结束了持续两个月的无煤发电,于9月重新启用退役的燃煤发电厂,使得煤电在英国发电量中的占比从零回升至3%。

Saxo Markets的高级市场分析师艾迪森·潘说:“我们注意到,随着天然气成本飙升,政府预计供暖需求也将达到顶峰,欧洲国家正在纷纷采购煤炭,以保障冬季能源供应。”

英国的电力危机是由北海(North Sea)异常温和的天气引发的,当地的海上风力发电通常能够满足该国25%的能源需求。随着风力停止,风能在英国能源结构中的占比降至7%。与此同时,随着欧盟逐渐摆脱新冠疫情阴霾,用电需求增长,天然气的价格在欧洲各地呈现飙涨。

但对于迫切需要天然气的欧洲能源供应商来说,不幸的是,中国也出现了类似的供需失衡。自今年5月以来,由于夏季异常干燥,水力发电减少,中国出现了周期性停电,多个制造业中心的生产线受阻。为了维持电网运行,中国电力生产商加大了天然气进口力度,推高了天然气价格。

现在,该国政府急于确保冬季供暖所需的电力,因而改变了多年来逐步消除煤矿产能过剩的政策,命令矿工“不惜一切代价”增加产量。对于已经投产的矿工来说,开采更多煤炭的成本并不是很高,而且由于煤炭价格处于历史高位,煤矿的利润率也相当可观。

但对于那些必须购买燃料的电力生产商来说,煤炭价格高不可攀,实在采购不起。

煤价疯涨

今年10月初,欧洲西北部的煤炭期货价格突破每吨275美元,短短四周内飙升63%。与此同时,纽卡斯尔煤炭——反映亚洲大宗商品价格的基准——在截至9月的12个月内飙涨了400%以上,达到每吨269美元。但随着煤炭价格疯涨,电力生产商推迟了补购这种高价大宗商品的计划。

“我认为,从经济上讲,我们已经尽可能地用尽煤炭的价值了。”能源咨询公司Lantau Group经理大卫·菲什曼说道。据国际能源署称,2020年6月,新太阳能发电装置的成本低于开设新燃煤电厂的成本,而目前煤炭价格飞涨,使得这种燃料在竞争力上更加不如可再生能源。

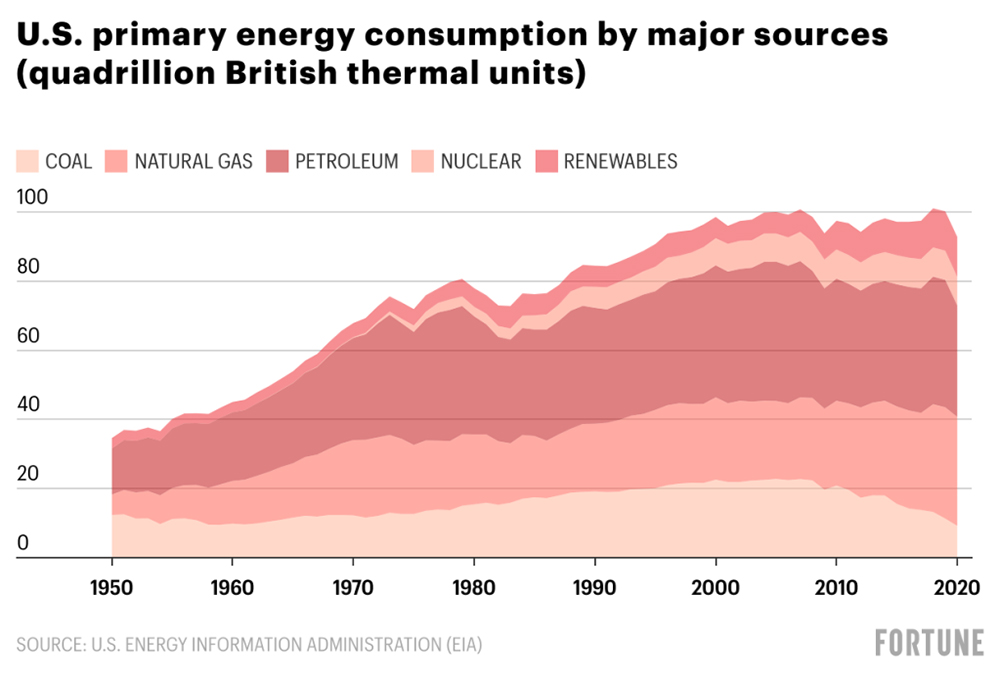

在发达经济体,煤矿企业已经考虑到煤炭需求下降的长期趋势,因此已经停止投资于产能扩张。根据美国能源信息署(U.S. Energy Information Administration)称,美国煤炭产量在2008年达到顶峰,去年则跌至1965年以来的最低水平。

与此同时,自2013年以来,美国能源供应商——那些烧煤而不是采煤的能源供应商——对电网的煤电产能贡献一直都没有增加。尽管今年美国煤电使用量将迎来自2014年以来的首次增长,但美国能源信息署预计,明年煤电使用量将重回下降通道。

据路透社(Reuters)报道,哪怕是在特朗普政府努力振兴美国煤炭业,废除奥巴马时代的清洁能源计划(Clean Power Plan,该计划指引能源部门减少燃煤电厂的碳排放)的时期,大多数能源生产商也仍然致力于逐步淘汰煤电。为什么呢?与可再生能源和天然气相比,煤炭成本太高。

菲什曼说:“我认为,煤炭只会变得越来越没有竞争力。”

寻找替代能源

然而,在亚洲,煤炭目前仍然占据主导地位。

燃煤发电厂为印度贡献了约70%的电力,为中国贡献了60%的电力。总体而言,亚洲在全球煤电总量中占大约80%,它也是全球煤炭增长最强劲的市场。根据亚洲气候变化投资者联盟(Asia Investor Group on Climate Change)的数据,在截至2030年的10年里,煤炭将为东南亚地区带来50%的电力增长。

除了煤炭是一种可靠且方便的能源外,印度尼西亚和澳大利亚的政府补贴、国家资助、矿业繁荣等因素也助力亚洲电力生产商将煤炭成本控制在相当可观的水平。从传统的燃煤电厂转向可再生能源电网的种种额外成本——例如关闭煤电厂、培训新技术人员和投资绿色技术——传统上也促使发展中国家的政府继续依赖煤炭。

但亚洲国家对煤炭项目的资助正在走向枯竭。今年9月,中国国家主席习近平承诺中国将停止为海外煤炭项目提供资金,这实际上切断了国际煤炭项目的最后一个公共筹资来源。此前,日本和韩国也相继承诺今年不再为煤炭项目提供融资。上周,亚洲开发银行(Asian Development Bank)宣布,计划通过收购煤电厂,让其提前停止运营,来加速煤炭在亚洲的消亡。

然而,消灭煤炭只是成功了一半。国际能源署预测,2020年至2040年间,仅东南亚地区的电力需求就将翻一番。地方政府将不得不寻找一些新的能源来源,来满足日益增长的用电需求。因此,如果《联合国气候变化框架公约》第二十六次缔约方大会想让煤炭成为历史,敦促发达国家增加对贫穷国家可再生能源项目的资助就将是一大关键。(财富中文网)

译者:万志文

Alok Sharma, president of the United Nations’ hotly anticipated COP26 climate change convention in Glasgow, has one overriding objective for the weeks-long event that starts on November 7: to “consign coal power to history.”

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), coal generates 40% of the world’s electricity needs, as well as 46% of global carbon emissions. To stave off the worst effects of climate change, the IEA says, governments need to slash coal’s share of global power supply to less than 1%.

But coal isn’t going down without a fight.

Coal usage has rebounded in the past year, wiping out declines in 2020 and interrupting a decades-long downward trend of use in advanced economies. Coal futures have erupted too, climbing 400% in some markets to reach record highs. Meanwhile, shares in U.S. coal producers have recovered from all-time lows and, in the case of Peabody Energy, rallied over 700% in 12 months.

However, coal's surging demand and scorching prices are more likely symptoms of the current energy crisis than signs of a sustained comeback. Long-term investment in coal is in decline and, economically, the competitiveness of renewables continues to climb. Coal stocks might be at a fever pitch now, but the spiking prices are signs of a commodity in its death throes rather than a market in revival.

King coal

According to the IEA, coal usage has declined across advanced economies for the past 20 years. In the U.S., that decline was advanced by the surge in domestic shale gas production. Natural gas is cheaper than coal and produces less carbon when burned, which means U.S. power producers have saved money and kept in line with federal regulations on carbon emissions by switching from coal to gas.

But, as a global energy crisis struck this summer, coal came back on the menu.

This year the U.S., squeezed by a shortage of natural gas, increased its use of coal-fired electricity for the first time since 2014. Across the pond, the U.K. ended its two-month run of coal-free power and switched mothballed coal-fired power plants back online in September, pumping coal’s share of the nation’s electricity generation back up from zero to 3%.

“We’re seeing the trend of European countries buying coal to secure energy supply in the winter, as the cost of natural gas spikes and governments expect heating demand to peak, too,” says Edison Pun, senior market analyst at Saxo Markets.

The U.K.’s power crisis was precipitated by exceptionally mild weather in the North Sea, where offshore windmills typically provide 25% of the country’s energy needs. As the wind stopped blowing, wind energy dropped to just 7% of the U.K.’s energy mix. At the same time, gas prices surged across Europe, as the bloc crawled out of the pandemic and increased its demand for electricity.

Unfortunately for European energy providers, desperate for gas, a similar demand-supply imbalance was playing out in China. Rolling power outages—prompted by a drop in hydropower generation over a peculiarly dry summer—have disrupted production lines in China’s manufacturing hubs since May. In order to keep grids running, Chinese power producers have turbocharged natural gas imports, heating up competition in the global markets and driving up prices.

Now Beijing, anxious to secure the power needed to heat homes throughout winter, has reversed course on a years-old policy of winding down overcapacity in coal mines and ordered miners to increase production “at any cost.” Although, for miners with operations already in place, the cost of digging out more coal isn’t prohibitive and, with coal prices at record highs, a mine’s profit margins are healthy, too.

But for power producers who have to buy the fuel, the high cost of coal has left them reluctant to pile in.

Too hot

At the beginning of October, coal futures in northwest Europe topped $275 per tonne, surging 63% in four weeks. Meanwhile, Newcastle coal—a benchmark that reflects the commodity’s price across Asia—ballooned over 400% in the 12 months to September, raging to $269 per tonne. But as coal prices surged, power producers held off on restocking the expensive commodity.

“I think, economically, we’ve squeezed just about all the use out of coal that we can,” says David Fishman, manager at energy consultancy Lantau Group. The cost of new solar power installations swooped below the price of opening new coal plants in June 2020, according to the IEA, and the current blistering price of coal is making the fuel even less competitive when compared with renewables.

In advanced economies, coal miners have already factored in the long-term trend of declining coal demand and have stopped investing in capacity expansion. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), coal production in the U.S. fell to its lowest level since 1965 last year, having peaked in 2008.

Meanwhile, U.S. energy suppliers—the ones that burn coal, not the ones that mine it—have added zero coal-fired capacity to the energy grid since 2013. Although coal-fired electricity usage will increase in the U.S. this year for the first time since 2014, the EIA expects that coal power’s downward trend will resume next year.

Even when the Trump administration fought to revitalize American coal and scrap the Obama-era Clean Power Plan—which instructed the energy sector to reduce carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants—a majority of energy producers remained committed to phasing out coal power, Reuters reports. The reason? Coal costs too much compared with renewables and gas.

Fishman says, “I can only see coal becoming increasingly uncompetitive.”

Building alternatives

In Asia, however, coal remains king—for now.

Coal-fired power plants generate some 70% of electricity in India as well as 60% of electricity in China. Asia, in general, generates roughly 80% of global coal-fired electricity and is also coal’s biggest growth market. According to the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change, coal will provide 50% of power growth across Southeast Asia in the 10 years to 2030.

In addition to coal being a reliable and convenient package of energy, government subsidies, state funding, and mining booms in Indonesia and Australia have kept coal costs palatable for Asian power producers. The added costs of switching from legacy coal-fired power plants to renewable energy grids—such as decommissioning coal plants, training new technicians, and investing in green tech—have traditionally encouraged governments in developing economies to continue their reliance on coal, too.

But Asian state financing for coal is drying up. In September, President Xi Jinping pledged China would stop funding coal projects overseas, effectively eliminating the last source of public funds for international coal projects, after Japan and South Korea committed to defund coal this year, too. And last week, the Asian Development Bank unveiled a scheme to hasten coal’s demise in Asia by buying coal plants and retiring them early.

Yet killing coal is only half the battle. The IEA predicts electricity demand across Southeast Asia alone will double between 2020 and 2040. Local governments will have to find some fresh fuel sources to satisfy the growing need. So if COP26 wants to consign coal to history, pressing wealthy countries to increase funding for renewable projects in poorer nations will be pivotal.