全球各大公司普遍未能履行其社会责任承诺:无论是承诺保护人权、行为道德,还是提供体面的工作环境。

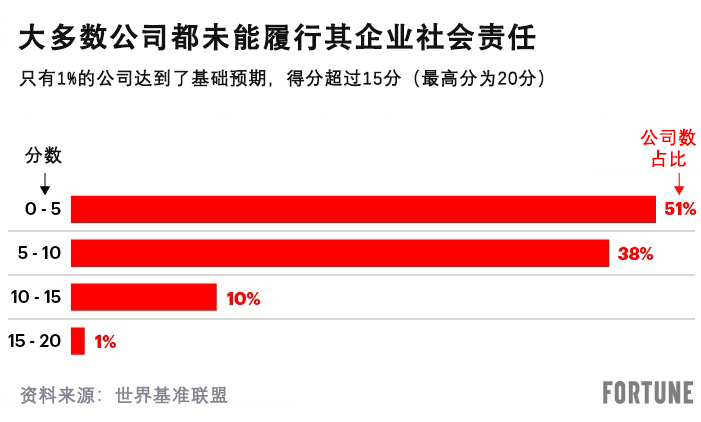

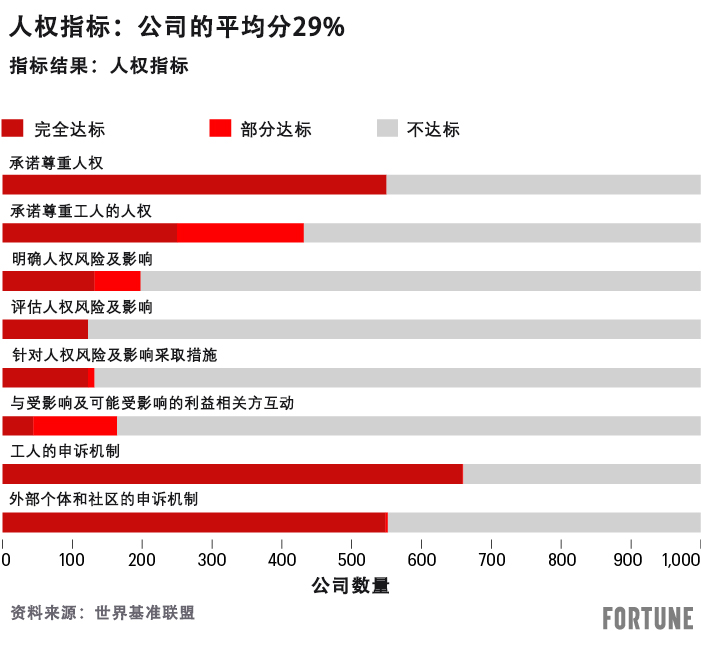

世界基准联盟(World Benchmarking Alliance)对60多个国家的1000家公司进行的一项研究显示,来自股东和公众的压力不足以使企业履行保护人权的承诺。世界基准联盟称,只有10家公司达到了联合国的可持续发展目标的基础预期。也就是说,全球各大公司的总体不达标率为99%。据世界基准联盟估计,这些公司总共创造了全球国内生产总值的25%,雇佣了超过5650万名员工。

“我们认为,如果只依靠自愿行为,就只能走到这了。”世界基准联盟的项目经理索菲亚·德尔·瓦勒在接受《财富》杂志采访时表示,“不可能实现需要完成的目标。”

随着宣布净零承诺的公司越来越多,可持续发展专家的怀疑也越来越重,因为他们的数据对公司履行承诺的能力提出了质疑。新冠疫情突显了在全球范围内采取协同行动的必要性,现在越来越多的科研人员呼吁加强监管、提起诉讼,甚至开展大规模罢工,以迫使公司采取行动。

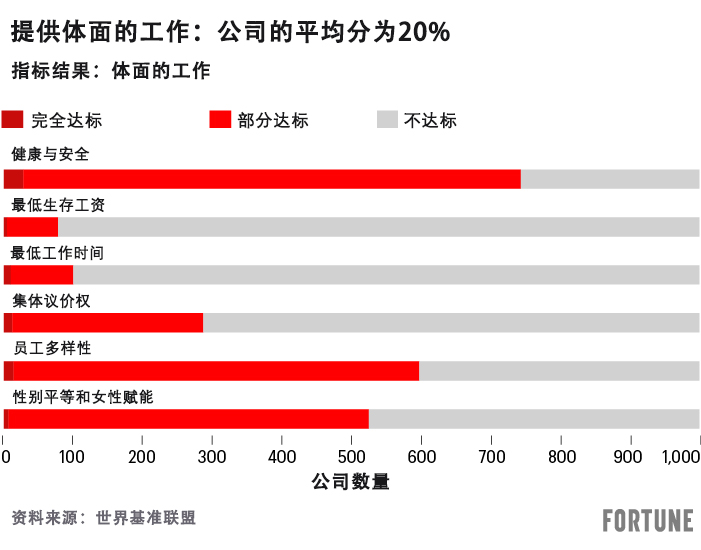

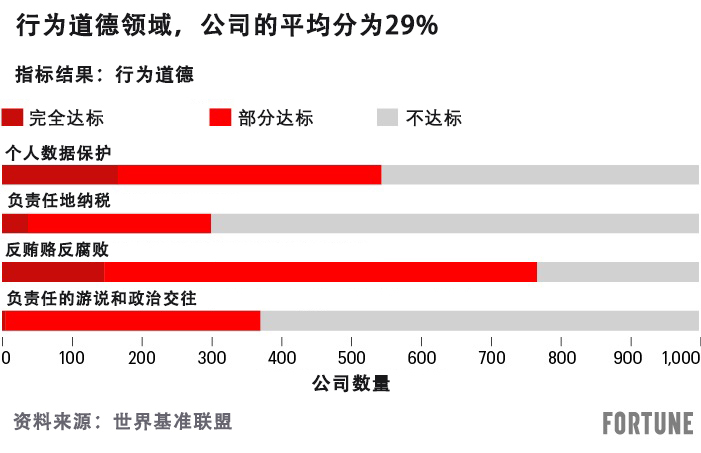

世界基准联盟评估了企业在人权领域采取的各类举措,包括支付最低生活工资、提供安全环境、在工作场所保障基本权利、针对侵犯行为提供补救措施等。世界基准联盟的研究还包括公司有无采取措施避免贿赂、公平支付税款、采取负责任的游说政策等。该研究涵盖的行业范围很广——从零售到电信,从农业到石油天然气等。世界基准联盟指出,超过一半的公司得分“低得令人失望”。

世界基准联盟称,因此,我们需要有效立法——而不仅仅是“打勾”,在法律的框架下强制公司在保护人权领域做得更多。

德尔·瓦勒指出,虽然全球性标准难以制定,但如果有一个足够大的市场完成了立法,就可能会产生连锁效应。例如,今年2月,欧盟颁布了一项尽职调查法律,要求企业查明其商业活动对人权问题(比如童工问题)和环境产生的不利影响,并敦促企业采取预防措施,消除影响,否则将面临罚款和制裁。德尔·瓦勒称,由于该法律要求企业对其整个生产链进行尽职调查,“对所有与欧洲相关的市场而言,都将产生巨大推动。”

随着网络黑客泄露个人数据的新闻出现得越来越频繁,隐私权也得到了越来越多的关注。然而,在世界基准联盟的研究中,只有大约一半公司曾经公开承诺在全球范围内保护个人数据。只有五分之一的公司发表过全球隐私保护声明。

虽然世界基准联盟呼吁所有公司采取全球性隐私保护措施,但德尔·瓦勒称,该领域发展如此之快,许多人权组织甚至无法及时了解现有风险。不过,随着越来越多的人受到影响,这些组织对相关问题的关注度也在不断提高。根据VPN提供商Atlas VPN的一项研究,2021年,约有59亿账户遭到了黑客入侵。

呼吁出台更多规定

2018年,欧盟出台了《通用数据保护条例》,在保护数据和隐私方面迈出了一大步。该条例规定,任何公司和组织都有义务确保收集到的欧盟公民的信息的安全。包括智利和韩国在内的一些非欧盟国家以及美国的加利福尼亚州、科罗拉多州和弗吉尼亚州也已经通过了隐私法。

即便如此,各国的数据保护仍将持续参差不齐,因为“出台一个全球性的隐私标准不太现实,”一个从事国际IT治理的商业协会ISACA(国际信息系统审计与控制协会)的隐私专业实践主管萨菲亚·卡齐说。但她说,有必要制定一个统一的监管标准。

“如果各国法规大同小异,公司就可以在整个企业内采取最佳做法。但如果监管规定各不相同,那么公司就可能在不同市场采取套利行为。”卡齐说,政策制定者和监管机构要加快步伐,推动变化。“不幸的是,股东和公众没有足够的影响力,让企业采取合乎道德的行为。”

无论是通过游说还是税收,大公司都会对监管产生巨大影响,却不愿意披露它们如何试图影响国家经济。世界基准联盟表示,为了迫使企业采取合乎道德的行动,需要对透明度做出规定,因为自发性措施已经失效。只有8%的受访公司披露了它们在游说和影响立法方面的花费。而愿意披露本公司在所在辖区缴税金额的公司只比8%多一点——9%。

正如世界基准联盟在报告中所言:“如果企业的影响力被当成秘密藏了起来,还能有多少信任呢?”气候变化立法的活动家会告诉你,答案是零。

世界基准联盟研究的人权课题已经为人们广泛接受,与此类似,人们也越来越普遍地认识到,一些公司的做法对环境造成的不利影响是有科学依据的。但在气候问题上,就像在人权问题上一样,通过立法来解决问题挑战更大。

气候变化智库InfluenceMap的执行董事迪伦·坦纳指出:“监管机构和政策制定者正在受到既得利益集团的阻挠。”由于气候变化,金融公司受到压力要求其停止资助损害环境的项目,而在决定为谁提供融资以及如何收费时,也有希望将人权承诺考虑在内。

不过,坦纳补充说,金融界能做的有限。

他表示:“金融部门的压力是小菜,决策者才是正餐。”

不过,最近出台的几项措施或许有助于削弱企业的影响力,推动人权立法向前发展。2021年,经济合作与发展组织(Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development)宣布,占全球GDP 90%的130个国家已经同意建立一个改革国际税收体系的新框架。世界基准联盟称,该举措具有积极意义,可能会提升透明度、加强问责。2021年11月,非营利组织国际财务报告标准基金会(International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation)宣布将成立国际可持续发展标准委员会(International Sustainability Standards Board),世界基准联盟称此举可以推动企业进行“可比较的、可靠的、一致的”信息披露。

新气候研究所(NewClimate Institute)赞同世界基准联盟的观点,认为企业的承诺不可靠,消费者和股东的压力也不足以让企业采取负责任的行动。新气候研究所在一份报告中评估了25家大公司的气候承诺,发现只有一家公司的净零承诺是“诚实合理的”,而大多数公司没有提出能够实现其承诺的具体目标。

新气候研究所的报告的作者之一、政策分析师希尔克·莫尔迪克却不愿意将立法的惰性完全归咎于游说和税收影响。她说,还有两个常见因素也是缺乏紧迫感的原因。“一些国家刚刚意识到有必要制定相关规定。”她还表示,官僚主义和政府反应迟缓也是重要因素。

此前,最高法院裁定,即便是对道德和诚信的一般性承诺也可能导致诉讼。因此,环境、社会和环境治理(ESG)领域的活动家今后可能会更频繁地诉诸法庭,迫使企业履行其公开承诺。在阿肯色州教师退休基金诉高盛集团一案中,投资者称,该公司对其承诺和合规举措的一般性声明具有误导性。Bracewell LLP律所的律师警告称,企业应该注意,即使做出的ESG承诺看起来司空见惯甚至不切实际,也可能带来法律风险。

还有一些不太现实的建议,比如三位气候研究人员在《气候与发展》(Climate and Development)杂志上发表的激进言论。他们警告道:“我们呼吁暂停气候变化研究,直到各国政府愿意真诚地履行责任,紧急调动资源,实现从本地到全球层面的协调行动。”

不过,一些公司仍然在继续做出承诺。美国国际集团在本月承诺,其承保和投资的项目最迟在2050年实现温室气体净零排放,计划“以一种透明的方式朝着可持续发展的方向前进”。

而且,并不是每个人的承诺都会落空。世界基准联盟给瑞士香精香料公司Firmenich的总分为11.5分(满分20分),其在提供体面的工作环境和行为道德方面的得分尤其高。Firmenich口味部门的主管埃马纽埃尔·布茨特瑞恩称,该排名是对本公司“为改善全球食品体系所做贡献”的认可。他说,公司的目标是运营“最可追溯、最可持续、最道德的价值链”。

世界基准联盟指出:“尽管一些公司已经将其人权承诺转化为有力的管理流程,但绝大多数公司仍然不知道、不展示它们是如何采取切实行动的。”

“全世界都看到了问题所在,”德尔·瓦勒说,但“与2018年相比,我们离目标更远了。”(财富中文网)

译者:Agatha

全球各大公司普遍未能履行其社会责任承诺:无论是承诺保护人权、行为道德,还是提供体面的工作环境。

世界基准联盟(World Benchmarking Alliance)对60多个国家的1000家公司进行的一项研究显示,来自股东和公众的压力不足以使企业履行保护人权的承诺。世界基准联盟称,只有10家公司达到了联合国的可持续发展目标的基础预期。也就是说,全球各大公司的总体不达标率为99%。据世界基准联盟估计,这些公司总共创造了全球国内生产总值的25%,雇佣了超过5650万名员工。

“我们认为,如果只依靠自愿行为,就只能走到这了。”世界基准联盟的项目经理索菲亚·德尔·瓦勒在接受《财富》杂志采访时表示,“不可能实现需要完成的目标。”

随着宣布净零承诺的公司越来越多,可持续发展专家的怀疑也越来越重,因为他们的数据对公司履行承诺的能力提出了质疑。新冠疫情突显了在全球范围内采取协同行动的必要性,现在越来越多的科研人员呼吁加强监管、提起诉讼,甚至开展大规模罢工,以迫使公司采取行动。

世界基准联盟评估了企业在人权领域采取的各类举措,包括支付最低生活工资、提供安全环境、在工作场所保障基本权利、针对侵犯行为提供补救措施等。世界基准联盟的研究还包括公司有无采取措施避免贿赂、公平支付税款、采取负责任的游说政策等。该研究涵盖的行业范围很广——从零售到电信,从农业到石油天然气等。世界基准联盟指出,超过一半的公司得分“低得令人失望”。

世界基准联盟称,因此,我们需要有效立法——而不仅仅是“打勾”,在法律的框架下强制公司在保护人权领域做得更多。

德尔·瓦勒指出,虽然全球性标准难以制定,但如果有一个足够大的市场完成了立法,就可能会产生连锁效应。例如,今年2月,欧盟颁布了一项尽职调查法律,要求企业查明其商业活动对人权问题(比如童工问题)和环境产生的不利影响,并敦促企业采取预防措施,消除影响,否则将面临罚款和制裁。德尔·瓦勒称,由于该法律要求企业对其整个生产链进行尽职调查,“对所有与欧洲相关的市场而言,都将产生巨大推动。”

随着网络黑客泄露个人数据的新闻出现得越来越频繁,隐私权也得到了越来越多的关注。然而,在世界基准联盟的研究中,只有大约一半公司曾经公开承诺在全球范围内保护个人数据。只有五分之一的公司发表过全球隐私保护声明。

虽然世界基准联盟呼吁所有公司采取全球性隐私保护措施,但德尔·瓦勒称,该领域发展如此之快,许多人权组织甚至无法及时了解现有风险。不过,随着越来越多的人受到影响,这些组织对相关问题的关注度也在不断提高。根据VPN提供商Atlas VPN的一项研究,2021年,约有59亿账户遭到了黑客入侵。

呼吁出台更多规定

2018年,欧盟出台了《通用数据保护条例》,在保护数据和隐私方面迈出了一大步。该条例规定,任何公司和组织都有义务确保收集到的欧盟公民的信息的安全。包括智利和韩国在内的一些非欧盟国家以及美国的加利福尼亚州、科罗拉多州和弗吉尼亚州也已经通过了隐私法。

即便如此,各国的数据保护仍将持续参差不齐,因为“出台一个全球性的隐私标准不太现实,”一个从事国际IT治理的商业协会ISACA(国际信息系统审计与控制协会)的隐私专业实践主管萨菲亚·卡齐说。但她说,有必要制定一个统一的监管标准。

“如果各国法规大同小异,公司就可以在整个企业内采取最佳做法。但如果监管规定各不相同,那么公司就可能在不同市场采取套利行为。”卡齐说,政策制定者和监管机构要加快步伐,推动变化。“不幸的是,股东和公众没有足够的影响力,让企业采取合乎道德的行为。”

无论是通过游说还是税收,大公司都会对监管产生巨大影响,却不愿意披露它们如何试图影响国家经济。世界基准联盟表示,为了迫使企业采取合乎道德的行动,需要对透明度做出规定,因为自发性措施已经失效。只有8%的受访公司披露了它们在游说和影响立法方面的花费。而愿意披露本公司在所在辖区缴税金额的公司只比8%多一点——9%。

正如世界基准联盟在报告中所言:“如果企业的影响力被当成秘密藏了起来,还能有多少信任呢?”气候变化立法的活动家会告诉你,答案是零。

世界基准联盟研究的人权课题已经为人们广泛接受,与此类似,人们也越来越普遍地认识到,一些公司的做法对环境造成的不利影响是有科学依据的。但在气候问题上,就像在人权问题上一样,通过立法来解决问题挑战更大。

气候变化智库InfluenceMap的执行董事迪伦·坦纳指出:“监管机构和政策制定者正在受到既得利益集团的阻挠。”由于气候变化,金融公司受到压力要求其停止资助损害环境的项目,而在决定为谁提供融资以及如何收费时,也有希望将人权承诺考虑在内。

不过,坦纳补充说,金融界能做的有限。

他表示:“金融部门的压力是小菜,决策者才是正餐。”

不过,最近出台的几项措施或许有助于削弱企业的影响力,推动人权立法向前发展。2021年,经济合作与发展组织(Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development)宣布,占全球GDP 90%的130个国家已经同意建立一个改革国际税收体系的新框架。世界基准联盟称,该举措具有积极意义,可能会提升透明度、加强问责。2021年11月,非营利组织国际财务报告标准基金会(International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation)宣布将成立国际可持续发展标准委员会(International Sustainability Standards Board),世界基准联盟称此举可以推动企业进行“可比较的、可靠的、一致的”信息披露。

新气候研究所(NewClimate Institute)赞同世界基准联盟的观点,认为企业的承诺不可靠,消费者和股东的压力也不足以让企业采取负责任的行动。新气候研究所在一份报告中评估了25家大公司的气候承诺,发现只有一家公司的净零承诺是“诚实合理的”,而大多数公司没有提出能够实现其承诺的具体目标。

新气候研究所的报告的作者之一、政策分析师希尔克·莫尔迪克却不愿意将立法的惰性完全归咎于游说和税收影响。她说,还有两个常见因素也是缺乏紧迫感的原因。“一些国家刚刚意识到有必要制定相关规定。”她还表示,官僚主义和政府反应迟缓也是重要因素。

此前,最高法院裁定,即便是对道德和诚信的一般性承诺也可能导致诉讼。因此,环境、社会和环境治理(ESG)领域的活动家今后可能会更频繁地诉诸法庭,迫使企业履行其公开承诺。在阿肯色州教师退休基金诉高盛集团一案中,投资者称,该公司对其承诺和合规举措的一般性声明具有误导性。Bracewell LLP律所的律师警告称,企业应该注意,即使做出的ESG承诺看起来司空见惯甚至不切实际,也可能带来法律风险。

还有一些不太现实的建议,比如三位气候研究人员在《气候与发展》(Climate and Development)杂志上发表的激进言论。他们警告道:“我们呼吁暂停气候变化研究,直到各国政府愿意真诚地履行责任,紧急调动资源,实现从本地到全球层面的协调行动。”

不过,一些公司仍然在继续做出承诺。美国国际集团在本月承诺,其承保和投资的项目最迟在2050年实现温室气体净零排放,计划“以一种透明的方式朝着可持续发展的方向前进”。

而且,并不是每个人的承诺都会落空。世界基准联盟给瑞士香精香料公司Firmenich的总分为11.5分(满分20分),其在提供体面的工作环境和行为道德方面的得分尤其高。Firmenich口味部门的主管埃马纽埃尔·布茨特瑞恩称,该排名是对本公司“为改善全球食品体系所做贡献”的认可。他说,公司的目标是运营“最可追溯、最可持续、最道德的价值链”。

世界基准联盟指出:“尽管一些公司已经将其人权承诺转化为有力的管理流程,但绝大多数公司仍然不知道、不展示它们是如何采取切实行动的。”

“全世界都看到了问题所在,”德尔·瓦勒说,但“与2018年相比,我们离目标更远了。”(财富中文网)

译者:Agatha

From protecting human rights to acting ethically to promoting decent working conditions, companies worldwide are failing to live up to their promises to be socially responsible.

Pressure from shareholders and the public just isn’t enough to force companies to uphold their pledges to protect human rights, according to a World Benchmarking Alliance study of 1,000 companies across more than 60 countries. Only 10 of those companies have achieved the fundamental expectations of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, according to the WBA. That’s a failure rate of 99% for these powerful companies, which the WBA estimates generate about 25% of the world’s gross domestic product and employ more than 56.5 million people.

“We definitely believe that voluntary measures can only take us so far,” says Sofía del Valle, engagement manager at WBA, in an interview with Fortune. “It’s not going to take us where we need to be.”

As more companies continue to announce new net-zero commitments, there is growing skepticism among sustainability experts whose data calls into question companies’ ability to deliver on these promises. With the pandemic highlighting the need for action on a global scale, there are now growing calls for regulation, lawsuits, and even mass walkouts by scientific researchers to force action.

In its assessment, the WBA examined corporate actions to measure a range of human rights including companies’ paying a living wage, providing a safe environment, embedding basic rights into their workplaces, and offering remedies for abuses. Also looked at was whether a company was acting ethically by eschewing bribery, paying fair taxes, and having a responsible lobbying policy. The industries covered were wide-ranging—from retail to telecommunications to agriculture to oil and gas. More than half the companies scored “disappointingly low,” the WBA notes.

That’s why effective legislation—not just a “tick-box exercise”—is needed to provide a framework that will force companies to take greater action in protecting human rights, the group says.

While it is difficult to enact worldwide standards, legislation in a big enough market can have a cascading effect, del Valle points out. In February, for instance, the European Union enacted a due diligence law that requires companies to identify adverse impacts that their activities have on human rights issues, such as child labor, and on the environment. The rules also push companies to prevent and end any of those impacts, or face fines and sanctions. Since the law requires companies to perform due diligence throughout their production chains, there “will be a massive push in all the markets that are linked to Europe,” del Valle notes.

The right to privacy has been gaining more attention as headlines of cyber-hacks exposing individuals’ data grow more frequent. Yet only about half the companies in the WBA study have made a public commitment to protecting personal data worldwide. Only one in five companies even has a global privacy statement.

While the WBA called on all companies to adopt global privacy practices, del Valle says the area is evolving so quickly that many human rights organizations aren’t up to speed on the risks. The groups are paying more attention to it, though, as more people are affected. In 2021, about 5.9 billion accounts were breached by hackers, according to a study from VPN provider Atlas VPN.

Calls for more regulation

The European Union took a big step toward protecting data and privacy in 2018 with its General Data Protection Regulation, which places obligations on companies and organizations to keep secure any details they collect on people in the EU. Some non-EU countries, ranging from Chile to South Korea, have adopted privacy laws, as have U.S. states including California, Colorado, and Virginia.

Even so, data protection will remain spotty because “it is unlikely that there will be a worldwide standard for privacy,” says Safia Kazi, privacy professional practices principal at ISACA, an international IT-governance business association. And a regulatory standard is necessary, she notes.

“If the regulations are more or less similar, companies can adopt enterprise-wide best practices. But if regulations have a lot of variation, it may make sense to arbitrage for various markets,” Kazi says, noting policymakers and regulators need to step up for the change to take place. “Unfortunately, shareholders and the general public don’t have the leverage needed to make enterprises act ethically.”

Large corporations yield great influence on regulation, either through lobbying or taxes, and show little inclination to be transparent about how they try to affect national economies. Transparency is needed to force companies to act ethically, the WBA says, because voluntary measures have failed. Only 8% of the companies surveyed disclose how much they spend on lobbying and efforts to shape legislation. Only a tick more—9%—disclose how much in taxes they pay for each jurisdiction where the company is a resident for tax purposes.

As the WBA says in the report, “How much trust is possible when corporate influence is veiled in secrecy?” Advocates of climate change legislation would tell you that the answer is none.

Like the universally accepted human rights tracked by the WBA, there has been a growing consensus on the science behind the adverse impacts some company practices have on the environment. But in climate, as in human rights, passing legislation to address the issue has proved more challenging.

“Regulators and policymakers are being scuppered by vested interests,” says Dylan Tanner, executive director of climate change think tank InfluenceMap. With climate change, there has been pressure on financial firms to stop funding projects that harm the environment, and there is some hope that lenders will factor in human rights commitments when deciding whom to provide with financing and how much to charge.

There’s a limit to what the financial world can do, though, Tanner adds.

“Pressure from the finance sector is the cherry, but the cake has to be the policymakers,” he says.

Still, several recent steps may help blunt corporate influence and move human rights legislation ahead. Last year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development announced that 130 countries representing 90% of global GDP had agreed to establish a new framework to reform the international tax system, a move that the WBA calls a positive step that may lead to greater transparency and accountability. In November, the nonprofit International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation said it would create an International Sustainability Standards Board that, the WBA says, may create disclosures that are “comparable, reliable, and consistent.”

NewClimate Institute echoes the WBA’s belief that corporate pledges are unreliable and consumer and shareholder pressure isn’t enough to make companies act responsibly. In a report assessing the climate commitments of 25 big companies, NewClimate found that only one company’s net-zero pledge was of “reasonable integrity,” while the majority failed to put forward targets that would meet their pledges.

One of the NewClimate report’s authors, policy analyst Silke Mooldijk, hesitates to blame all the legislative inertia on lobbying and tax influence, however. She says two common failings also contribute to the lack of urgency. “Some countries have only just realized that these regulations are needed,” she says, noting the slowness of bureaucracy and government is also playing a role.

ESG activists may turn to the courts more often to force companies to meet their public pledges in the wake of a Supreme Court decision that even general statements like a commitment to ethics and integrity can lead to a lawsuit. In the case of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, investors claimed the company’s generic statements regarding its commitments and compliance initiatives were misleading in the face of later-revealed conflicted transactions. Companies should be mindful that ESG pledges may carry legal risks even if they appear generic or aspirational in nature, Bracewell LLP lawyers warned.

Also on the table are less likely tactics, such as the radical pitch by three climate researchers in the journal Climate and Development. “We call for a moratorium on climate change research until governments are willing to fulfill their responsibilities in good faith and urgently mobilize coordinated action from the local to global levels,” the scientists warned.

Still, some companies continue to make pledges. American International Group this month committed to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions across its underwriting and investment portfolios by no later than 2050, planning a “transparent journey toward sustainability advancement.”

And not everyone’s pledges fall short. The WBA gave Firmenich, the Swiss fragrance and flavors company, an overall score of 11.5 out of 20, ranking it especially high on providing decent workplaces and acting ethically. Emmanuel Butstraen, president of the taste and beyond division at Firmenich, called the ranking a recognition of the company’s “contributions to improving the global food system.” The company’s goal, he said, is to operate the “most traceable, sustainable, and ethical value chain.”

“Although some companies have translated their human rights commitments into robust management processes, the vast majority are still failing to ‘know and show’ how they have taken tangible action,” the WBA notes.

“The whole world saw what we knew was the problem,” del Valle says, but “we are farther away from the goals than we were in 2018.”