今年2月1日的上午,高盛集团(Goldman Sachs)重新开放了其位于曼哈顿下城、高44层的总部办公室。但是,首席执行官苏德巍(David Solomon)却对当日的员工出勤率十分不满。在奥密克戎变异毒株席卷纽约后,高盛的办公楼被封禁一个月。幸运的是,现在高盛大楼已经重新开放,员工又可以在办公室一起工作了,这正是苏德巍热切期盼的场景,而且全公司上下都知道这位首席执行官的想法。然而即便在两周前就已经发出了通知,但直到中午时分,总部的1万名员工中却只有差不多5000人出现在办公室,这让苏德巍感到了挑战。

不温不火的首日出勤率是反常现象,还是某种预兆?

远程办公在全球范围内已经是大势所趋,但苏德巍也不怕别人说他是“老古董”。科技巨头们,包括赛富时(Salesforce)、推特(Twitter)、Meta(Facebook 母公司)、Spotify都已经允许世界各地成千上万的员工全职远程工作。高盛在华尔街的一些竞争对手,例如花旗集团(Citigroup)和瑞银(UBS),也会允许员工定期居家工作,并表示该政策将增强公司在招聘和留住优秀人才方面的竞争优势。苏德巍表达过与之相反的观点。他在2021年2月的一次金融行业会议上表示,远程办公“对我们来说并不理想,它不是新常态。而是一种失常,我们将尽快纠正。”

上述观点发表一年后的今天,苏德巍仍然初心不改。2月1日,重回办公室的第一天,苏德巍告诉《财富》杂志:“高盛集团吸引着数以千计出类拔萃的年轻人前来学习如何工作,创建优质人脉网络,并努力为客户做好服务,这是我们的制胜秘诀。而其中最关键的是大家在一起,与经验更丰富的同事合作共事。如果我们打破这种联结,将远程办公作为常态,虽然大家仍然能够完成大量工作。”当然,高盛自身的表现证明了这一点:过去两年是高盛有史以来业绩最好的两年,公司报告显示,2021年利润达到创纪录的216亿美元。(仅去年一年,苏德巍就拿到了3500万美元薪酬。)“但是如此一来,我们独特的基础也将被磨灭。”

因此,苏德巍得出结论:“高盛要保持这一独特的文化基础,必须将大家重新聚在一起。”

苏德巍是在徒劳地抗拒潮流?还是说,正如他主张的那样,整个商界对新冠疫情带来的一系列临时需求反应过度,忽视了人类彼此间根深蒂固的力量?所有公司都必须直面上述问题,毕竟利益攸关。提倡混合办公制度的企业在几年后可能会发现,员工面对面交流的减少导致公司的文化和创造力双双萎缩,而要恢复则可能需更长时间。但如果上述风险压根没有发生,那么坚持要求员工坐班的雇主就将面临地租超支损失。更严重的是,他们可能无法吸引并留住优秀人才。

作为极端案例,高盛的做法极具启发意义。可能没有哪个大公司比高盛更重视面对面工作,正因如此,当初新冠疫情来袭,摆在高盛面前的是一场独具威胁的危机。

高盛的办公室遍布世界六大洲,公司很早就预见了新冠疫情的威胁。2020年开年不久,高盛的全球各大职能主管和其他高管开始举行电话会议,讨论集团的新冠疫情应对计划,每周至少两次,一直延续至今。与会高管很快得出了清晰的结论:新冠病毒将从亚洲传播到欧洲再到北美;供应链将被打乱,变得脆弱不堪;关闭办公场所将不可避免。

新冠疫情迫使高盛的管理层做出了一系列艰难决定。1979年,德高望重的高级合伙人约翰·怀特黑德在负责编撰高盛的12大业务原则时写道:“我们做任何事情都强调团队合作。”但如果同一团队的成员各自居家办公,这个团队还可以正常运转吗?”

人力主管本特利·德拜尔是澳大利亚人,曾经在强生公司(Johnson & Johnson)任职,2020年1月加入高盛,当时正值新冠疫情来袭。在高盛内部的播客中,他回忆到自己刚上任就要“做出可能连公司领导层都极不待见的各类调整,直到新冠疫情的严重性更加明显后,这种窘境才有所改善”。个中滋味,苦不堪言。我不得不及时采取行动,改变“那些被奉为圭臬、无人敢碰的公司政策和做法。”

2020年3月中旬,与大多数其他大型银行同步,高盛关闭了在美洲、欧洲、中东和非洲的所有办公场所,亚洲办公室在此之前就已经关闭。纽约总部仅允许一小部分人进出,包括少数需要使用总部的设备来做市的交易员和零星的几位高管。整个新冠疫情期间,苏德巍都坚持正常到公司上班。

转眼间,高盛有98%的员工都开始居家办公,这实在太魔幻了。德拜尔回忆道:“哪怕是在新冠疫情高峰期的1月时问我,这种情况会不会出现在高盛,我都会认为你是疯了。”

与大多数的其他大型银行相比,高盛并没有更早要求员工返回办公室,相反,有些情况下高盛给出的期限甚至更宽容。但从一开始,高盛的管理层就表示,无论员工何时重返办公室,都要确保办公室能够随时正常运转。正因如此,供应链的中断尤为引人担忧。

高盛的部分办公室内部有很多项目依靠供应商管理,比如:内部诊所、差旅安排、技术服务等等。据知情人士透露,高盛在复工后需要一众供应商同步到现场办公,而高盛深知在新冠疫情停工期间,这些供应商“可能拿不到报酬。”但是为确保各服务供应商随叫随到,高盛在新冠疫情期间仍然坚持向停工的供应商支付服务费。

新冠疫情初期,苏德巍担心的另一个大问题是即将在夏季入职的新员工。在大多数公司,新人入职可能仅仅是一件需要操办的事情,但对高盛而言,这可是头等大事。若想明白其中缘由,并进而理解新冠疫情为何让高盛如此受伤,就必须先了解高盛不同寻常的运营模式。

高盛是一家拥有153年悠久历史的华尔街巨头,但它又是一家非常年轻化的公司。在高盛的全球43900名员工中,约有73%是千禧一代或Z世代,50%的员工年龄在20岁到30岁之间。但随着职场晋升,“后浪团”的人数会逐渐减少,因为高盛内部的职级架构极其扁平,职场新人和高管之间只有4层基础职级,分别是:分析员、助理、副总裁(美国以外地区称为执行董事)和董事总经理。虽然高盛自1999年上市以来一直没有成为合伙企业,但一小部分常务董事可以兼获合伙人头衔。现有的合伙人其实是指参与单独奖金计划的董事总经理。

每年夏天都会有大约3000名新员工入职高盛,其中大多数人刚刚获得学士学位。据培训公司Wall Street Oasis报道,高盛的分析师在入职首年的薪酬丰厚,全球范围内的平均薪金达到136400美元,虽然略低于各大主要银行的平均薪酬(143000美元),但其培训、人脉和威望对应聘者非常有吸引力。新人通常会报名参加为期两年的培训项目,在项目接近尾声时,高盛会设法留住其中的佼佼者,哪怕他们原本想去商学院继续深造。而其余的大部分人将离开高盛从事其他工作。正常情况下,在两年项目结束后,十个人中只会留下两个人。

对高盛和年轻分析师们而言,这种模式都大有裨益,即使他们中的大多数人最终会选择离开高盛。通过密切观察,高盛从成群出类拔萃的新员工中遴选出最优秀的人才,其余的人则能够带着镀金的履历闯荡世界。许多人会到金融行业的其他领域就业。一位已经退休的高盛高级合伙人表示:“像KKR集团、黑石(Blackstones)这样的企业都在坐等高盛招聘到优秀人才,替他们培训好,然后伺机挖墙脚。”在全球范围内,这些离开高盛的新人有的会一路晋升,担任要职,其所在公司常常也会变成高盛的客户。

苏德巍解释了高盛体系的运转方式。“我们每年为公司的各大职能部门招聘数以千计的优秀本科毕业生。这其中的一部分人会留下来。很多人会离开,去追求别的事业。但他们都会因为曾经在高盛工作而感到自豪。他们会时常回想起这段经历和其中的收获。此外,他们来自世界各地,都是极其聪颖、非常有趣的人。试想你今年也是22岁,刚刚加入一个由这些同龄人组成的3000人的群体,彼此交流互动会是一个多么美妙的体验。更不必说这个群体中还有23至26岁的其他年轻人,其中不乏专业层面的交流,还可以帮助你打造一个持续一生的‘朋友圈’。这就是高盛的生态系统,富有活力而且异常强大。”

这一点也被竞争对手和行业专家所广泛认同。在《财富》杂志最新发布的“全球最受赞赏的公司”榜单中,决定排名先后的投票者,包括业内顶级高管和董事,以及关注该行业的股票分析师们,共同将高盛推上业内人才管理第一名的宝座,领先于摩根大通(JPMorgan Chase)、摩根士丹利(Morgan Stanley)、美国银行(Bank of America)、花旗集团(Citigroup)、汇丰银行(HSBC)等众多企业。

有了这一背景信息,就不难理解在过去两年内,高盛为何那样伤神。苏德巍说:“新冠疫情中,我们发现一个现象,如果你每天在家除了努力工作,就是看电视,那么在高盛工作所带来的那种美好而独特的体验就会慢慢消失。”如果你独自在家工作,那么持续一生的人际网络、向全球顶尖人才学习的机会、由数以千计荣誉等身的同龄人所创造的那种令人陶醉的氛围就都会消失殆尽。而随着时间的推移,高盛可能会失去其独特的魅力和光环。对高盛而言,远程办公远不仅仅是一个挑战,还会破坏“公司的生态系统”。

问题可能会愈发严重。内森·里泽在2019年1月入职高盛的伦敦办事处,担任分析师,2021年4月便选择离开,因为他感觉自己已经精疲力尽,需要为自己的健康着想。他告诉《财富》杂志:“我见证过新冠疫情和封锁的至暗时刻。”他将自己的经历写成文章,发表在《纽约杂志》(New York)上,文中写道:“当我开始居家工作时,最先意识到的是高盛的办公室福利有多好。”例如公司内部的医护中心和健身房。“无论是在办公室一起加班到深夜,还是在健身房里并肩挥洒汗水,努力与他人共同追求卓越,都充满着团结人心的魔力。而这一切在线上环境中是不可能实现的。”里泽告诉《财富》杂志,他离开高盛是因为不喜欢工作本身,如果不是这样,“我想立即回到那里。”

里泽的经历绝非少数。此次新冠疫情对高盛的分析师们来说十分残酷,原因有两个。首先,在办公室上班,有很多因素让人觉得再辛苦也值得;其次就是强制居家办公期间,分析员们承担着与往常相同的高强度工作,却失去了亲自到公司上班所带来的好处。除此之外,本就辛苦的工作突然变得更加艰难,这已经是危险信号。

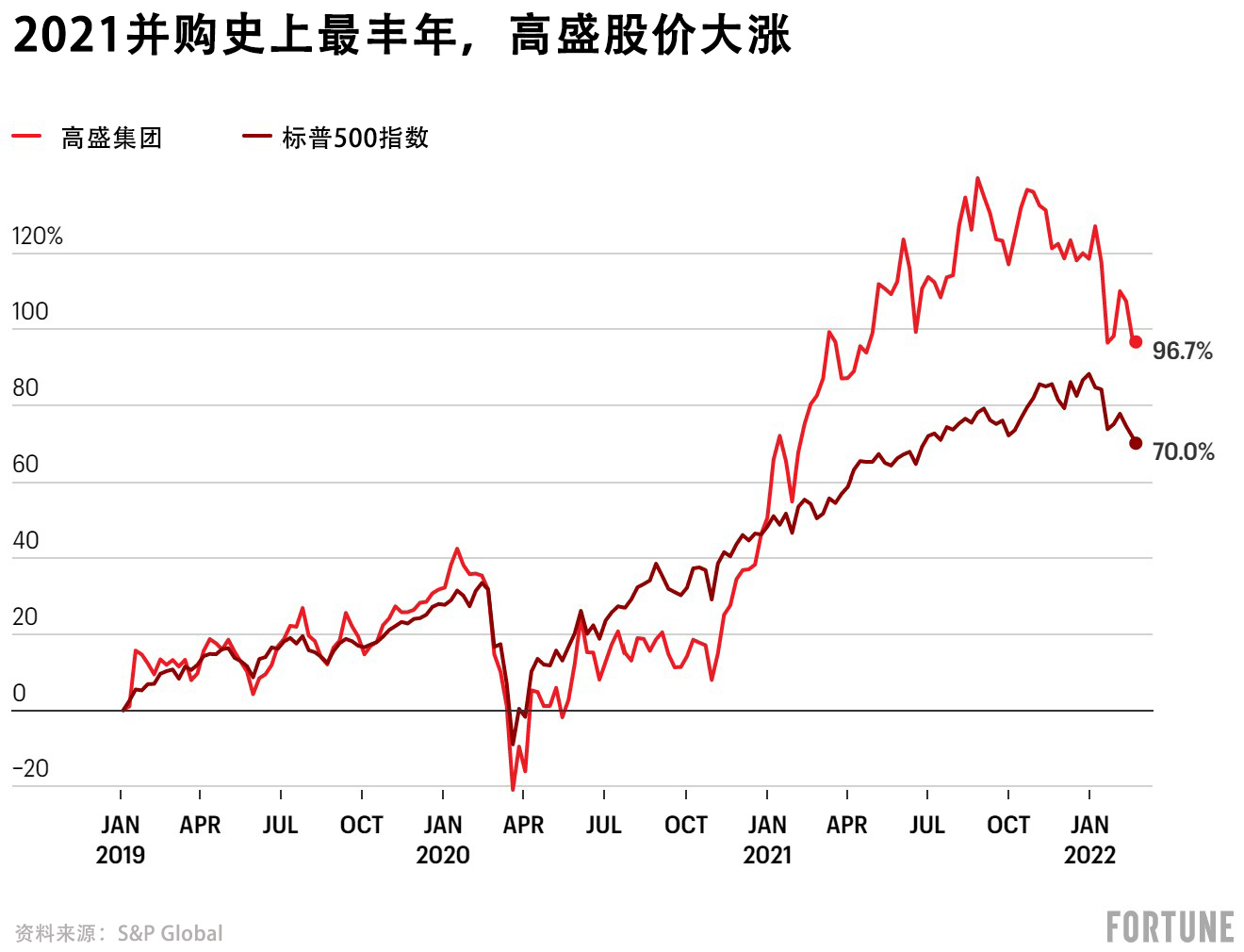

高盛为期两年的分析师项目从来都是一场鏖战:每周工作80小时到100小时,压力巨大,充满着不可能完成的节点。新冠疫情骤然改变了很多行业,其中一些行业(比如电子商务、视频直播、互联网服务)顺势崛起,另一些行业(例如酒店业、旅游业、能源产业)则深受打击,然而所有这些行业都迫切地需要金融服务。受此影响,高盛在2020年的营收增长了22%,2021年更是猛增至33%,创全球并购交易史上最高年收入纪录,也让高盛在全球企业购并业务的排名中稳坐头把交椅。2021年也是史上IPO数量最多的一年,高盛在该业务领域同样排名第一位。但对高盛的分析师们来说,这意味着更为漫长的工作周,和更大的压力。

据《纽约邮报》(New York Post)后来报道,早在2020年4月,就有居家办公的高盛分析师抱怨:工作时无法使用公司的高性能电脑,只能使用自己的,而且以前在办公室加班到晚上8点会有25美元的餐补现在也没有了。不满情绪“偷走”了员工的时间和注意力,然而工作量还在不断增加。10个月后,高盛的旧金山办公室的13名分析师联合向领导们发送了一份PPT,其中详细罗列了他们的各种不满:上周平均工作105小时,上个月每周工作98小时,平均凌晨3点才能够睡觉,身体和心理健康状况急转直下。

新冠疫情同样削弱了其他一些重要的活动体验。比哈佛大学(Harvard University)都难进的高盛暑期实习项目,在2020年首次全方位通过线上方式开展,正常10周的项目时长也被压缩到了5周,整个项目简直是黯淡无光。而另一件同样史无前例的事情,更让高盛的领导层感到惭愧:3000名通过线上方式“报到”开启高盛职业生涯的新员工,从未获得他们求职时所期待的那种面对面的工作经历。

2020年6月,高盛重新开放了纽约地区的办公室,但鼓励员工尽可能继续居家工作。新冠肺炎的病例数从2020年夏末开始激增,在2020年和2021年之交的冬季里达到前所未有的峰值,直到被近期出现的奥密克戎疫情超越。即使在这种情况下,高盛还是尽可能的展现了面对面工作的魔力。苏德巍表示,“花时间花精力亲自与客户会面是与客户建立关系的基础”,在历史性全球疫情的大背景下尤为如此。就在那个冬天,美国航空公司(American Airlines)通过抵押内部“常旅客计划”融资75亿美元,高盛处理了这笔交易。美国航空公司的首席财务官德里克·克尔后来在内部银行家在线会议上表示,高盛之所以拿到这个订单,是因为它们是唯一一家来到美国航空的得州总部、现场争取订单的公司。克尔告诉《财富》杂志:“第二天早上,马上有四家银行打来电话,想约我面谈。”

还是那个冬天,2021年2月,苏德巍正在思忖如何避免重蹈上年夏天的覆辙。他在一次华尔街在线会议上说:“我希望今年夏天新来的年轻人不用再远程报到,我希望这3000名新人获得更多面对面交流的机会、一手的学徒体验和导师指导。因为这些对高盛来说极为重要。”

这次苏德巍终于如愿以偿了。如今,他表示:“我认为这对我们来说是巨大的成就。据我所知,去年夏天,我们是纽约唯一一家把所有暑期分析师和合伙人全部聚集到一起的公司,他们在纽约获得了完整的项目体验。为了创造这个机会,我们付出了巨大的努力。”

在此之前,高盛已经宣布了2021年6月亚洲以外全球各地重返办公室的日期,可以看出,公司对返岗办公的期待和鼓励。自2021年9月7日起,任何进入高盛美国办公室的人都必须完成新冠疫苗的完全接种,2022年2月1日起,还必须接种加强针。

这或许是近两年来第一次,人们能够大胆相信,高盛的远程办公常态化时代已经终结。

然而,大考才刚刚开始。新冠病毒是否永远地改变了以办公室为核心的工作秩序?还是说这种所谓的转变会出乎权威人士和民意调查者的意料,最终会慢慢消亡?最近的一项民调显示,只有3%的白领愿意每周五天都到办公室坐班,还有许多人表示如果要求每周连续五天坐班,他们就会主动辞职。然而,在高盛每周可能是连续上班六或七天,在当今的劳动力市场上,这般不近人情的用人模式能否存续?

有人认为,高盛吸引人才的能力已经是今非昔比,不能继续对新员工提出如此高的要求。记者、作家兼前华尔街投资银行家威廉·D·科汉,著有《金钱与权力:高盛如何统治世界》(Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World)等书。他指出:“成为并购银行家不再是顶尖人才追求的目标,他们已经转战私募股权或科技领域。”哈佛商学院(Harvard Business School)的2021届毕业生中,有23%进入咨询行业,19%进入技术领域,14%进入私募股权,8%进入对冲基金,7%进入风险投资,只有4%进入高盛所在的投资银行业。

有人可能会认为这些数字具有误导性,因为从商学院毕业后去投行工作已经是昔日的职业模式。科汉说:“我在1987年从哥伦比亚商学院(Columbia Business School)毕业时,只有两种选择:要么进投行,要么做咨询。如今,如果你即将取得MBA学位并打算去华尔街做助理,别人就会认为你有点失败。”当下更明智的做法是“大学毕业后,在华尔街找到一份分析师工作,然后等待被私募股权公司招走,而且是越快越好。”

高盛正在面临着对优秀本科毕业生吸引力不足的压力,上述局面无疑是雪上加霜。怎奈竞争激烈。雇主品牌咨询公司优兴咨询(Universum)对全球超过100万名学生(包括本科生)进行的最新调查显示,对最有志向的学生来说,摩根士丹利、瑞银和高盛在受青睐投行中的受欢迎度几乎并列第一。

然而,即使可以持续吸引其一贯推崇的“干将型选手”,高盛或会在其他方面付出代价。波士顿咨询公司(Boston Consulting Group)的高级合伙人德博拉·洛维奇表示:“如果你支持文化多样性,我们的数据显示,少数派人才,比如黑人、拉丁裔、亚洲人和女性都更喜欢居家办公。因此,如果有其他雇主愿意满足这种偏好,就会导致你很难招到人才。”洛维奇称,这种情况很不妙,因为“人才多样性是优化产品、进行创新的关键。有大量数据能够证实这一点。失去人才多样性,公司会吃亏的。”洛维奇的核心观点是:“企业面临的真正挑战,不是要不要组织员工回到办公室,而是让混合办公制度真正有效运转起来。”

苏德巍认为此类担忧是把问题过于简单化了,也可以说是理由不充分。他将员工多元化作为头等大事,例如,坚持要求新任分析师中至少50%为女性。高盛在2020年首次达成这一目标,新一任分析师中的女性职员占比达到55%。如今的高盛与其他大型银行一样,会向社会公布少数族裔代表的相关数据。其少数族裔员工数量处于行业中间位置。2020年,黑人员工占高盛美国员工总数的6.8%(最新可得数据),达到了美国黑人人口比例的一半。而且这些数字还在上升,这也是评定公司管理人员奖金的指标之一。

关于顶尖人才的吸引,高盛的首席执行官苏德巍认为,将其比作华尔街与科技巨头之争未免“过于草率”。每个行业都会吸引到各种各样的人才,从事不尽相同的工作。他表示,“在Facebook,做软件工程师的人和做广告销售的人拥有完全不同的目标和抱负。同样,来高盛做投资银行家或交易员的人与担任软件工程师的人,其目标也不相同。”高盛要做的是让人岗匹配,而不是在每个职位空缺上都胜其他用人单位一筹。苏德巍相信,这一点他仍然能够做到。

坦白讲,即使只有3%的白领愿意全职在办公室工作,高盛只需要吸引这3%中的一小部分人。女性和少数族裔或许更加偏爱远程办公,但同样,在这些群体中,苏德巍还是有机会找到他想要的、极少数与众不同的人才。

在高盛,另一个经常被忽视却耐人寻味的细节是:平日里随便选一天,都有很多员工在远程办公。高盛的公司文化里,一向很照顾因为意外原因而需要留在家中的员工。高盛有着慷慨的员工探亲假政策。公司高层的管理者们经常出差拜访客户,在路上工作在所难免。内森·里泽说,当初他被工作累得精疲力尽向领导们请假时,他们立刻同意了,并表示休息多长时间都可以。他告诉《财富》杂志:“你的领导们要求很高,但当你提出要求时他们也会立马答应。”说到关键处,他打了个响指。高盛的文化“允许员工处理个人琐事”,苏德巍说,“但这与早上醒来随口就说:‘哦,外面下雨了,我今天不想去上班了。’是两码事。”

现在和未来的顶尖年轻人才是否会接受高盛的这种文化,答案尚未可知。15 年前曾经在高盛工作,现已投身其他行业的一位高管回忆道:“在当时那种技术工具条件下,我就问过自己这个问题,我所做的工作真的需要我在公司坐班吗?”

本已悬殊的代际差别可能正在进一步扩大。近期,高盛总部的日出勤率徘徊在60%至70%之间,虽然好于2月1日重返办公室当天的表现,但即使将正常的差旅和其他因素考虑在内,也没有恢复正常水平。一位已经退休的高级合伙人评论说:“不仅高盛,所有公司,返回办公室办公最大阻力都是来自最年轻的员工。这确实让人诧异。年长的员工可不会这样。”

苏德巍的理念与整个美国商界显得格格不入。在美国,居家工作已经是新常态,很多写字楼正在被改建为公寓,绿树成荫的郊区房屋价格一飞冲天,但苏德巍并不受大趋势所约束,他还是独树一帜,全神贯注地发展高盛。他说:“我认为,我们行业的工作方式与五年前并无差异,五年后也不会变。”

像所有优秀的华尔街银行家一样,苏德巍喜欢“反其道而行之”。是赢是输,利益攸关。(财富中文网)

译者:潘文秀

审校:夏林

今年2月1日的上午,高盛集团(Goldman Sachs)重新开放了其位于曼哈顿下城、高44层的总部办公室。但是,首席执行官苏德巍(David Solomon)却对当日的员工出勤率十分不满。在奥密克戎变异毒株席卷纽约后,高盛的办公楼被封禁一个月。幸运的是,现在高盛大楼已经重新开放,员工又可以在办公室一起工作了,这正是苏德巍热切期盼的场景,而且全公司上下都知道这位首席执行官的想法。然而即便在两周前就已经发出了通知,但直到中午时分,总部的1万名员工中却只有差不多5000人出现在办公室,这让苏德巍感到了挑战。

不温不火的首日出勤率是反常现象,还是某种预兆?

远程办公在全球范围内已经是大势所趋,但苏德巍也不怕别人说他是“老古董”。科技巨头们,包括赛富时(Salesforce)、推特(Twitter)、Meta(Facebook 母公司)、Spotify都已经允许世界各地成千上万的员工全职远程工作。高盛在华尔街的一些竞争对手,例如花旗集团(Citigroup)和瑞银(UBS),也会允许员工定期居家工作,并表示该政策将增强公司在招聘和留住优秀人才方面的竞争优势。苏德巍表达过与之相反的观点。他在2021年2月的一次金融行业会议上表示,远程办公“对我们来说并不理想,它不是新常态。而是一种失常,我们将尽快纠正。”

上述观点发表一年后的今天,苏德巍仍然初心不改。2月1日,重回办公室的第一天,苏德巍告诉《财富》杂志:“高盛集团吸引着数以千计出类拔萃的年轻人前来学习如何工作,创建优质人脉网络,并努力为客户做好服务,这是我们的制胜秘诀。而其中最关键的是大家在一起,与经验更丰富的同事合作共事。如果我们打破这种联结,将远程办公作为常态,虽然大家仍然能够完成大量工作。”当然,高盛自身的表现证明了这一点:过去两年是高盛有史以来业绩最好的两年,公司报告显示,2021年利润达到创纪录的216亿美元。(仅去年一年,苏德巍就拿到了3500万美元薪酬。)“但是如此一来,我们独特的基础也将被磨灭。”

因此,苏德巍得出结论:“高盛要保持这一独特的文化基础,必须将大家重新聚在一起。”

苏德巍是在徒劳地抗拒潮流?还是说,正如他主张的那样,整个商界对新冠疫情带来的一系列临时需求反应过度,忽视了人类彼此间根深蒂固的力量?所有公司都必须直面上述问题,毕竟利益攸关。提倡混合办公制度的企业在几年后可能会发现,员工面对面交流的减少导致公司的文化和创造力双双萎缩,而要恢复则可能需更长时间。但如果上述风险压根没有发生,那么坚持要求员工坐班的雇主就将面临地租超支损失。更严重的是,他们可能无法吸引并留住优秀人才。

作为极端案例,高盛的做法极具启发意义。可能没有哪个大公司比高盛更重视面对面工作,正因如此,当初新冠疫情来袭,摆在高盛面前的是一场独具威胁的危机。

高盛的办公室遍布世界六大洲,公司很早就预见了新冠疫情的威胁。2020年开年不久,高盛的全球各大职能主管和其他高管开始举行电话会议,讨论集团的新冠疫情应对计划,每周至少两次,一直延续至今。与会高管很快得出了清晰的结论:新冠病毒将从亚洲传播到欧洲再到北美;供应链将被打乱,变得脆弱不堪;关闭办公场所将不可避免。

新冠疫情迫使高盛的管理层做出了一系列艰难决定。1979年,德高望重的高级合伙人约翰·怀特黑德在负责编撰高盛的12大业务原则时写道:“我们做任何事情都强调团队合作。”但如果同一团队的成员各自居家办公,这个团队还可以正常运转吗?”

人力主管本特利·德拜尔是澳大利亚人,曾经在强生公司(Johnson & Johnson)任职,2020年1月加入高盛,当时正值新冠疫情来袭。在高盛内部的播客中,他回忆到自己刚上任就要“做出可能连公司领导层都极不待见的各类调整,直到新冠疫情的严重性更加明显后,这种窘境才有所改善”。个中滋味,苦不堪言。我不得不及时采取行动,改变“那些被奉为圭臬、无人敢碰的公司政策和做法。”

2020年3月中旬,与大多数其他大型银行同步,高盛关闭了在美洲、欧洲、中东和非洲的所有办公场所,亚洲办公室在此之前就已经关闭。纽约总部仅允许一小部分人进出,包括少数需要使用总部的设备来做市的交易员和零星的几位高管。整个新冠疫情期间,苏德巍都坚持正常到公司上班。

转眼间,高盛有98%的员工都开始居家办公,这实在太魔幻了。德拜尔回忆道:“哪怕是在新冠疫情高峰期的1月时问我,这种情况会不会出现在高盛,我都会认为你是疯了。”

与大多数的其他大型银行相比,高盛并没有更早要求员工返回办公室,相反,有些情况下高盛给出的期限甚至更宽容。但从一开始,高盛的管理层就表示,无论员工何时重返办公室,都要确保办公室能够随时正常运转。正因如此,供应链的中断尤为引人担忧。

高盛的部分办公室内部有很多项目依靠供应商管理,比如:内部诊所、差旅安排、技术服务等等。据知情人士透露,高盛在复工后需要一众供应商同步到现场办公,而高盛深知在新冠疫情停工期间,这些供应商“可能拿不到报酬。”但是为确保各服务供应商随叫随到,高盛在新冠疫情期间仍然坚持向停工的供应商支付服务费。

新冠疫情初期,苏德巍担心的另一个大问题是即将在夏季入职的新员工。在大多数公司,新人入职可能仅仅是一件需要操办的事情,但对高盛而言,这可是头等大事。若想明白其中缘由,并进而理解新冠疫情为何让高盛如此受伤,就必须先了解高盛不同寻常的运营模式。

高盛是一家拥有153年悠久历史的华尔街巨头,但它又是一家非常年轻化的公司。在高盛的全球43900名员工中,约有73%是千禧一代或Z世代,50%的员工年龄在20岁到30岁之间。但随着职场晋升,“后浪团”的人数会逐渐减少,因为高盛内部的职级架构极其扁平,职场新人和高管之间只有4层基础职级,分别是:分析员、助理、副总裁(美国以外地区称为执行董事)和董事总经理。虽然高盛自1999年上市以来一直没有成为合伙企业,但一小部分常务董事可以兼获合伙人头衔。现有的合伙人其实是指参与单独奖金计划的董事总经理。

每年夏天都会有大约3000名新员工入职高盛,其中大多数人刚刚获得学士学位。据培训公司Wall Street Oasis报道,高盛的分析师在入职首年的薪酬丰厚,全球范围内的平均薪金达到136400美元,虽然略低于各大主要银行的平均薪酬(143000美元),但其培训、人脉和威望对应聘者非常有吸引力。新人通常会报名参加为期两年的培训项目,在项目接近尾声时,高盛会设法留住其中的佼佼者,哪怕他们原本想去商学院继续深造。而其余的大部分人将离开高盛从事其他工作。正常情况下,在两年项目结束后,十个人中只会留下两个人。

对高盛和年轻分析师们而言,这种模式都大有裨益,即使他们中的大多数人最终会选择离开高盛。通过密切观察,高盛从成群出类拔萃的新员工中遴选出最优秀的人才,其余的人则能够带着镀金的履历闯荡世界。许多人会到金融行业的其他领域就业。一位已经退休的高盛高级合伙人表示:“像KKR集团、黑石(Blackstones)这样的企业都在坐等高盛招聘到优秀人才,替他们培训好,然后伺机挖墙脚。”在全球范围内,这些离开高盛的新人有的会一路晋升,担任要职,其所在公司常常也会变成高盛的客户。

苏德巍解释了高盛体系的运转方式。“我们每年为公司的各大职能部门招聘数以千计的优秀本科毕业生。这其中的一部分人会留下来。很多人会离开,去追求别的事业。但他们都会因为曾经在高盛工作而感到自豪。他们会时常回想起这段经历和其中的收获。此外,他们来自世界各地,都是极其聪颖、非常有趣的人。试想你今年也是22岁,刚刚加入一个由这些同龄人组成的3000人的群体,彼此交流互动会是一个多么美妙的体验。更不必说这个群体中还有23至26岁的其他年轻人,其中不乏专业层面的交流,还可以帮助你打造一个持续一生的‘朋友圈’。这就是高盛的生态系统,富有活力而且异常强大。”

这一点也被竞争对手和行业专家所广泛认同。在《财富》杂志最新发布的“全球最受赞赏的公司”榜单中,决定排名先后的投票者,包括业内顶级高管和董事,以及关注该行业的股票分析师们,共同将高盛推上业内人才管理第一名的宝座,领先于摩根大通(JPMorgan Chase)、摩根士丹利(Morgan Stanley)、美国银行(Bank of America)、花旗集团(Citigroup)、汇丰银行(HSBC)等众多企业。

有了这一背景信息,就不难理解在过去两年内,高盛为何那样伤神。苏德巍说:“新冠疫情中,我们发现一个现象,如果你每天在家除了努力工作,就是看电视,那么在高盛工作所带来的那种美好而独特的体验就会慢慢消失。”如果你独自在家工作,那么持续一生的人际网络、向全球顶尖人才学习的机会、由数以千计荣誉等身的同龄人所创造的那种令人陶醉的氛围就都会消失殆尽。而随着时间的推移,高盛可能会失去其独特的魅力和光环。对高盛而言,远程办公远不仅仅是一个挑战,还会破坏“公司的生态系统”。

问题可能会愈发严重。内森·里泽在2019年1月入职高盛的伦敦办事处,担任分析师,2021年4月便选择离开,因为他感觉自己已经精疲力尽,需要为自己的健康着想。他告诉《财富》杂志:“我见证过新冠疫情和封锁的至暗时刻。”他将自己的经历写成文章,发表在《纽约杂志》(New York)上,文中写道:“当我开始居家工作时,最先意识到的是高盛的办公室福利有多好。”例如公司内部的医护中心和健身房。“无论是在办公室一起加班到深夜,还是在健身房里并肩挥洒汗水,努力与他人共同追求卓越,都充满着团结人心的魔力。而这一切在线上环境中是不可能实现的。”里泽告诉《财富》杂志,他离开高盛是因为不喜欢工作本身,如果不是这样,“我想立即回到那里。”

里泽的经历绝非少数。此次新冠疫情对高盛的分析师们来说十分残酷,原因有两个。首先,在办公室上班,有很多因素让人觉得再辛苦也值得;其次就是强制居家办公期间,分析员们承担着与往常相同的高强度工作,却失去了亲自到公司上班所带来的好处。除此之外,本就辛苦的工作突然变得更加艰难,这已经是危险信号。

高盛为期两年的分析师项目从来都是一场鏖战:每周工作80小时到100小时,压力巨大,充满着不可能完成的节点。新冠疫情骤然改变了很多行业,其中一些行业(比如电子商务、视频直播、互联网服务)顺势崛起,另一些行业(例如酒店业、旅游业、能源产业)则深受打击,然而所有这些行业都迫切地需要金融服务。受此影响,高盛在2020年的营收增长了22%,2021年更是猛增至33%,创全球并购交易史上最高年收入纪录,也让高盛在全球企业购并业务的排名中稳坐头把交椅。2021年也是史上IPO数量最多的一年,高盛在该业务领域同样排名第一位。但对高盛的分析师们来说,这意味着更为漫长的工作周,和更大的压力。

据《纽约邮报》(New York Post)后来报道,早在2020年4月,就有居家办公的高盛分析师抱怨:工作时无法使用公司的高性能电脑,只能使用自己的,而且以前在办公室加班到晚上8点会有25美元的餐补现在也没有了。不满情绪“偷走”了员工的时间和注意力,然而工作量还在不断增加。10个月后,高盛的旧金山办公室的13名分析师联合向领导们发送了一份PPT,其中详细罗列了他们的各种不满:上周平均工作105小时,上个月每周工作98小时,平均凌晨3点才能够睡觉,身体和心理健康状况急转直下。

新冠疫情同样削弱了其他一些重要的活动体验。比哈佛大学(Harvard University)都难进的高盛暑期实习项目,在2020年首次全方位通过线上方式开展,正常10周的项目时长也被压缩到了5周,整个项目简直是黯淡无光。而另一件同样史无前例的事情,更让高盛的领导层感到惭愧:3000名通过线上方式“报到”开启高盛职业生涯的新员工,从未获得他们求职时所期待的那种面对面的工作经历。

2020年6月,高盛重新开放了纽约地区的办公室,但鼓励员工尽可能继续居家工作。新冠肺炎的病例数从2020年夏末开始激增,在2020年和2021年之交的冬季里达到前所未有的峰值,直到被近期出现的奥密克戎疫情超越。即使在这种情况下,高盛还是尽可能的展现了面对面工作的魔力。苏德巍表示,“花时间花精力亲自与客户会面是与客户建立关系的基础”,在历史性全球疫情的大背景下尤为如此。就在那个冬天,美国航空公司(American Airlines)通过抵押内部“常旅客计划”融资75亿美元,高盛处理了这笔交易。美国航空公司的首席财务官德里克·克尔后来在内部银行家在线会议上表示,高盛之所以拿到这个订单,是因为它们是唯一一家来到美国航空的得州总部、现场争取订单的公司。克尔告诉《财富》杂志:“第二天早上,马上有四家银行打来电话,想约我面谈。”

还是那个冬天,2021年2月,苏德巍正在思忖如何避免重蹈上年夏天的覆辙。他在一次华尔街在线会议上说:“我希望今年夏天新来的年轻人不用再远程报到,我希望这3000名新人获得更多面对面交流的机会、一手的学徒体验和导师指导。因为这些对高盛来说极为重要。”

这次苏德巍终于如愿以偿了。如今,他表示:“我认为这对我们来说是巨大的成就。据我所知,去年夏天,我们是纽约唯一一家把所有暑期分析师和合伙人全部聚集到一起的公司,他们在纽约获得了完整的项目体验。为了创造这个机会,我们付出了巨大的努力。”

在此之前,高盛已经宣布了2021年6月亚洲以外全球各地重返办公室的日期,可以看出,公司对返岗办公的期待和鼓励。自2021年9月7日起,任何进入高盛美国办公室的人都必须完成新冠疫苗的完全接种,2022年2月1日起,还必须接种加强针。

这或许是近两年来第一次,人们能够大胆相信,高盛的远程办公常态化时代已经终结。

然而,大考才刚刚开始。新冠病毒是否永远地改变了以办公室为核心的工作秩序?还是说这种所谓的转变会出乎权威人士和民意调查者的意料,最终会慢慢消亡?最近的一项民调显示,只有3%的白领愿意每周五天都到办公室坐班,还有许多人表示如果要求每周连续五天坐班,他们就会主动辞职。然而,在高盛每周可能是连续上班六或七天,在当今的劳动力市场上,这般不近人情的用人模式能否存续?

有人认为,高盛吸引人才的能力已经是今非昔比,不能继续对新员工提出如此高的要求。记者、作家兼前华尔街投资银行家威廉·D·科汉,著有《金钱与权力:高盛如何统治世界》(Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World)等书。他指出:“成为并购银行家不再是顶尖人才追求的目标,他们已经转战私募股权或科技领域。”哈佛商学院(Harvard Business School)的2021届毕业生中,有23%进入咨询行业,19%进入技术领域,14%进入私募股权,8%进入对冲基金,7%进入风险投资,只有4%进入高盛所在的投资银行业。

有人可能会认为这些数字具有误导性,因为从商学院毕业后去投行工作已经是昔日的职业模式。科汉说:“我在1987年从哥伦比亚商学院(Columbia Business School)毕业时,只有两种选择:要么进投行,要么做咨询。如今,如果你即将取得MBA学位并打算去华尔街做助理,别人就会认为你有点失败。”当下更明智的做法是“大学毕业后,在华尔街找到一份分析师工作,然后等待被私募股权公司招走,而且是越快越好。”

高盛正在面临着对优秀本科毕业生吸引力不足的压力,上述局面无疑是雪上加霜。怎奈竞争激烈。雇主品牌咨询公司优兴咨询(Universum)对全球超过100万名学生(包括本科生)进行的最新调查显示,对最有志向的学生来说,摩根士丹利、瑞银和高盛在受青睐投行中的受欢迎度几乎并列第一。

然而,即使可以持续吸引其一贯推崇的“干将型选手”,高盛或会在其他方面付出代价。波士顿咨询公司(Boston Consulting Group)的高级合伙人德博拉·洛维奇表示:“如果你支持文化多样性,我们的数据显示,少数派人才,比如黑人、拉丁裔、亚洲人和女性都更喜欢居家办公。因此,如果有其他雇主愿意满足这种偏好,就会导致你很难招到人才。”洛维奇称,这种情况很不妙,因为“人才多样性是优化产品、进行创新的关键。有大量数据能够证实这一点。失去人才多样性,公司会吃亏的。”洛维奇的核心观点是:“企业面临的真正挑战,不是要不要组织员工回到办公室,而是让混合办公制度真正有效运转起来。”

苏德巍认为此类担忧是把问题过于简单化了,也可以说是理由不充分。他将员工多元化作为头等大事,例如,坚持要求新任分析师中至少50%为女性。高盛在2020年首次达成这一目标,新一任分析师中的女性职员占比达到55%。如今的高盛与其他大型银行一样,会向社会公布少数族裔代表的相关数据。其少数族裔员工数量处于行业中间位置。2020年,黑人员工占高盛美国员工总数的6.8%(最新可得数据),达到了美国黑人人口比例的一半。而且这些数字还在上升,这也是评定公司管理人员奖金的指标之一。

关于顶尖人才的吸引,高盛的首席执行官苏德巍认为,将其比作华尔街与科技巨头之争未免“过于草率”。每个行业都会吸引到各种各样的人才,从事不尽相同的工作。他表示,“在Facebook,做软件工程师的人和做广告销售的人拥有完全不同的目标和抱负。同样,来高盛做投资银行家或交易员的人与担任软件工程师的人,其目标也不相同。”高盛要做的是让人岗匹配,而不是在每个职位空缺上都胜其他用人单位一筹。苏德巍相信,这一点他仍然能够做到。

坦白讲,即使只有3%的白领愿意全职在办公室工作,高盛只需要吸引这3%中的一小部分人。女性和少数族裔或许更加偏爱远程办公,但同样,在这些群体中,苏德巍还是有机会找到他想要的、极少数与众不同的人才。

在高盛,另一个经常被忽视却耐人寻味的细节是:平日里随便选一天,都有很多员工在远程办公。高盛的公司文化里,一向很照顾因为意外原因而需要留在家中的员工。高盛有着慷慨的员工探亲假政策。公司高层的管理者们经常出差拜访客户,在路上工作在所难免。内森·里泽说,当初他被工作累得精疲力尽向领导们请假时,他们立刻同意了,并表示休息多长时间都可以。他告诉《财富》杂志:“你的领导们要求很高,但当你提出要求时他们也会立马答应。”说到关键处,他打了个响指。高盛的文化“允许员工处理个人琐事”,苏德巍说,“但这与早上醒来随口就说:‘哦,外面下雨了,我今天不想去上班了。’是两码事。”

现在和未来的顶尖年轻人才是否会接受高盛的这种文化,答案尚未可知。15 年前曾经在高盛工作,现已投身其他行业的一位高管回忆道:“在当时那种技术工具条件下,我就问过自己这个问题,我所做的工作真的需要我在公司坐班吗?”

本已悬殊的代际差别可能正在进一步扩大。近期,高盛总部的日出勤率徘徊在60%至70%之间,虽然好于2月1日重返办公室当天的表现,但即使将正常的差旅和其他因素考虑在内,也没有恢复正常水平。一位已经退休的高级合伙人评论说:“不仅高盛,所有公司,返回办公室办公最大阻力都是来自最年轻的员工。这确实让人诧异。年长的员工可不会这样。”

苏德巍的理念与整个美国商界显得格格不入。在美国,居家工作已经是新常态,很多写字楼正在被改建为公寓,绿树成荫的郊区房屋价格一飞冲天,但苏德巍并不受大趋势所约束,他还是独树一帜,全神贯注地发展高盛。他说:“我认为,我们行业的工作方式与五年前并无差异,五年后也不会变。”

像所有优秀的华尔街银行家一样,苏德巍喜欢“反其道而行之”。是赢是输,利益攸关。(财富中文网)

译者:潘文秀

审校:夏林

CEO David Solomon could not have been pleased at the turnout when Goldman Sachs reopened its 44-story headquarters in lower Manhattan on the morning of Feb. 1. The building had been closed for a month as COVID-19’s Omicron variant swept through town. Now, finally, with luck, Goldman employees could resume working together in person, as Solomon emphatically wants them to do, without further shutdowns. Yet as of late morning on that Tuesday, only about 5,000 of Goldman’s 10,000 HQ workers had shown up—despite having had over two weeks’ notice, and in seeming defiance of Solomon’s pointed desire to get everyone back in the office as soon as safely possible.

Is that tepid turnout an anomaly? Or is it a harbinger?

Solomon has risked looking like a Neanderthal as remote work has gone mainstream worldwide. Top-tier tech firms—Salesforce, Twitter, Meta (Facebook’s parent), Spotify—have told thousands of employees they’re liberated to work remotely full-time, anywhere in the world. Some of Goldman’s Wall Street rivals, including Citigroup and UBS, are letting staffers work from home regularly and claim the policy will give the firms a competitive advantage in recruiting and retaining excellent employees. Solomon has said the opposite. Remote work “is not ideal for us, and it’s not a new normal,” he famously told a finance industry conference in February 2021. “It’s an aberration that we’re going to correct as quickly as possible.”

Now, a year after making that declaration, Solomon isn’t backing down. “The secret sauce to our organization is, we attract thousands of really extraordinary young people who come to Goldman Sachs to learn to work, to create a network of other extraordinary people, and work very hard to serve our clients,” he told Fortune on that back-to-the-office day, Feb. 1. “Part of the secret sauce is that they come together and collaborate and work with people that are much more experienced than they are. If you break that all down and scatter it around”—that is, if you make remote work the new normal—“you can still get a bunch of work done.” Goldman’s own performance bears that last statement out: The past two years were Goldman’s best ever, with the company reporting a record profit of $21.6 billion in 2021. (And Solomon collected $35 million in compensation last year alone.) “But you start to fray the foundational things that make the place so unique.”

Solomon’s inevitable conclusion: “For Goldman Sachs to retain that cultural foundation, we have to bring people together.”

Is Solomon futilely resisting the tide? Or, as he believes, is the rest of the business world overreacting to the pandemic’s temporary demands and ignoring the deep-rooted power of human beings with one another? Every organization must face such questions, and the stakes are high. Businesses that embrace hybrid work may discover only years later that with less face-to-face employee interaction, their culture and creativity have withered—and recovering could take more years. But if that risk proves baseless, employers that insist on presence in the workplace will overspend on real estate and, far worse, may not attract and keep the best workers.

Goldman’s experience is instructive as an extreme case. Perhaps no major company values in-person work more highly—which means that when the pandemic arrived, the firm faced a uniquely threatening crisis.

*****

With offices on six continents, Goldman foresaw the threat of COVID-19 early. Soon after 2020 dawned, functional chiefs and other executives globally began group pandemic planning calls twice weekly, sometimes more often, which continue today. A few facts quickly became clear: The virus would spread from Asia to Europe to North America; supply chains would be disrupted and unreliable; closing offices would be unavoidable.

For Goldman’s top leaders, the pandemic forced painful decisions. “We stress teamwork in everything we do,” wrote John Whitehead, a revered senior partner, when he listed the firm’s 12 principles in 1979. But would teams really work if their members were alone in their homes?

HR chief Bentley de Beyer, an Australian who was previously at Johnson & Johnson, arrived at Goldman in January 2020, just as the pandemic hit. He recalled in a podcast for internal distribution that he immediately faced issues of “making adjustments that might be wildly unpopular, even with some of our business leaders at the time, until the seriousness of the outbreak became more obvious.” It was wrenching. Changing policies and practices that “may have been sacred cows in the firm—something that no one in the firm would have dared touch or assess or make any adjustments to—we’ve had to do that in real time.”

Goldman closed all its offices in the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa in mid-March, in step with most other big banks; Asian offices had closed earlier. The only people allowed in New York headquarters were a small number of traders who needed to make markets using technology in the building, plus a few top executives. Throughout the pandemic, Solomon never stopped going to the office.

Suddenly 98% of the firm’s workforce was working from home—a surreal experience. De Beyer recalled that “if you’d asked me, even in January, would that be possible at a firm like Goldman Sachs, I would have thought you were a little crazy.”

Goldman did not require employees to return to the office sooner than most other big banks, and in some cases it waited longer. But from the beginning, senior leaders focused intensely on making sure offices would be fully functional from the moment employees returned, whenever that might be. That’s why disrupted supply chains were especially worrying.

Goldman relies on vendors to manage its in-house medical clinics in some offices, its travel programs, its technology services, and more; the firm “needed those vendors to be there” when it was time to return to the office, says someone familiar with the firm’s thinking, and it knew that during the pandemic those vendors “potentially weren’t going to get paid.” To ensure they’d be there when needed, Goldman continued to pay some vendors through the pandemic, even when no money was owed.

Another of Solomon’s top concerns in the pandemic’s early days was the firm’s incoming class of new hires, arriving in the summer. That issue would be concerning at most companies, but at Goldman it’s supremely important. To understand why, and to understand more broadly why the pandemic was so traumatic for Goldman, it’s necessary to understand the firm’s unusual operating model.

Contrary to the popular conception of a big, 153-year-old Wall Street firm, Goldman Sachs is an extremely young company. Some 73% of its 43,900 employees are millennials or Gen Z; 50% of employees are in their twenties. That herd gets thinned out quickly as it rises through the hierarchy, which is remarkably flat. Just four basic job categories separate the rookies from the top executives: analyst, associate, vice president (called executive director outside the U.S.), and managing director. A small percentage of managing directors gain an additional title, partner, though Goldman hasn’t been a partnership since it went public in 1999; today’s partners are managing directors who participate in a separate bonus plan.

Each summer some 3,000 new employees arrive, most of them having just received bachelor’s degrees. Those first-year analysts are well paid, receiving an average globally of $136,400 in salary and bonus, reports the Wall Street Oasis training firm—slightly below the major-bank average ($143,000) because applicants value so highly the Goldman training, network, and street cred. The rookies typically sign up for a two-year program, near the end of which Goldman will try to entice the very best not to go elsewhere, not even to go to business school, but to stay at the firm. Most of the rest will leave for other jobs. It isn’t unusual for 80% of an incoming class to be gone after two years.

That model offers multiple benefits for Goldman and for the young analysts, even the large majority who don’t stay with the firm. Goldman attracts an ultra-elite group of new hires and then observes them closely to identify the very best. The rest go out into the world with the gleaming Goldman credential. Many land elsewhere in the financial world. “The KKRs, the Blackstones, and others count on Goldman Sachs to hire really good people and train them for them, and try to pick ’em off,” says a retired senior partner. Those recruits sometimes rise to high positions at firms globally, which often become Goldman customers.

Solomon explains how it all works as a system. “We hire thousands of people out of undergraduate school every year—really extraordinary people across all areas of the firm. Some of them stay. A lot go on to do other things. But they will be very proud of the fact that they worked for Goldman Sachs. They will think back generously on their experience and what it taught them.” In addition, “they’re super-smart, really interesting people from all over the world. If you’re a 22-year-old who has just been thrown into a pot of 3,000 other 22-year-olds—let alone the 23-, 24-, 25-, and 26-year-olds—you get to interact with them. Some of that interaction is professional. Some of it becomes a friends’ network that you carry with you in life. That is the ecosystem of the firm. That’s a very powerful ecosystem.”

Competitors and industry experts agree. In Fortune’s latest list of the World’s Most Admired Companies, the voters who determine the ranking—top industry executives and directors, plus stock analysts who follow the industry—rated Goldman No. 1 in people management in its industry, ahead of JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, Citigroup, HSBC, and more.

Against that background, it becomes clear why the past two years were so agonizing for the firm. Solomon says, “One of the things we saw in the pandemic is, if all you’re doing is a lot of work and looking at a television screen, a lot of the things that make that experience so fantastic disappear.” The lifelong network, the learning from some of the world’s best, the heady atmosphere created by thousands of staggeringly accomplished peers—working alone from home, they were gone. Over time, the firm could lose its unique allure, its aura. For Goldman, remote work was much worse than just a challenge. It undermined the very “ecosystem of the firm.”

The problems could be much worse. Nathan Risser joined Goldman at its London office as an analyst in January 2019 and left in April 2021, burned out and needing to protect his health. “I saw the darkest days of the pandemic and lockdown,” he tells Fortune. He wrote an article about his experience, published in New York, observing that “the first thing I noticed when I started working from home was how important the in-office perks at Goldman had become”—things like the medical center and on-site gym. “There’s something about striving to achieve the exceptional alongside others, whether by working late nights in the office or putting in a hard hour in the gym, that pulls people together. And that can’t happen in a virtual environment.” Risser tells Fortune he left because he didn’t like the work, but if it were otherwise, “I’d want to be back in there immediately.”

His experience was far from rare. The pandemic was brutal for Goldman analysts for two reasons. It wasn’t just that being stuck at home left them with all the usual hard work but without the in-office factors that made the Goldman experience bearable and valuable. In addition, the hard work suddenly turned much harder, which is saying something.

The Goldman two-year analyst program has always been trial by fire: 80- to 100-hour weeks, intense pressure, impossible deadlines. The pandemic violently disrupted an array of industries, some for better (e-commerce, video streaming, internet services), some for worse (hospitality, travel, energy), all of them urgently needing financial services. Result: Goldman’s revenue jumped 22% in 2020 and then leaped a further 33% in 2021—the all-time biggest year in mergers and acquisitions globally, with Goldman ranking No. 1 worldwide in handling M&A deals. 2021 was also the biggest-ever year for IPOs, and Goldman ranked No. 1 in handling those. For analysts, the long weeks grew even longer, the pressure heavier.

As early as April 2020, the New York Post later reported, analysts were complaining about having to use their own computers instead of the better ones at work and not getting the $25 meal stipend available after 8 p.m. at the office—irritations that stole time and attention from the growing workload. Ten months later, a group of 13 analysts in the San Francisco office sent bosses a PowerPoint deck detailing their grievances: working an average of 105 hours in the previous week, 98 hours a week in the previous month, getting to bed at 3 a.m. on average, mental and physical health declining sharply.

The pandemic gravely weakened other critical experiences. For the first time, Goldman’s summer interns—a group that’s harder to get into than Harvard—faced an entirely digital program in 2020, lasting just five weeks instead of the usual 10, a sad substitute for the real thing. Even more mortifying for the firm’s leaders was another unprecedented event: The incoming class of 3,000 new employees would “arrive” digitally and start working for Goldman having never known the in-person experience they signed up for.

Goldman reopened its New York area offices in June 2020 but encouraged employees to continue working from home if they could. COVID case counts began rising steeply at summer’s end, peaking in the winter of 2020–21 at levels not matched until the recent Omicron variant arrived. Yet even then, Goldman deployed the power of physical presence when it could. “Building relationships with clients comes from showing up and making the effort to be there,” Solomon says—especially amid a historic global pandemic. When American Airlines borrowed $7.5 billion collateralized by its frequent-flier program that winter, Goldman handled the transaction. American’s CFO, Derek Kerr, later told an online meeting of the airline’s bankers that Goldman got the deal because it was the only firm that showed up at American’s Texas headquarters to make its pitch. “The next morning I had calls from four banks wanting to come see me,” he tells Fortune.

That same winter, in February 2021, Solomon was already thinking hard about avoiding a repeat of summer 2020. “I don’t want another class of young people arriving at Goldman Sachs this summer remotely,” he told an online Wall Street conference—“3,000 young people coming in that aren’t getting more direct contact, direct apprenticeship, direct mentorship. That’s very, very important to us.”

He got his wish. He says now, “I think it made a huge difference for us. Last summer I believe we were the only firm that had all of our summer analysts and associates in New York, 100% there, for their whole summer experience. We worked very hard to create that opportunity.”

By then the firm had announced dates for a return to the office—expected, not just encouraged—in June 2021 at locations worldwide except in Asia. As of last Sept. 7, anyone entering Goldman’s U.S. offices had to be fully vaccinated; as of Feb. 1, 2022, everyone must now be fully vaccinated and boostered.

For the first time in nearly two years, it became realistic to believe that just maybe, regular remote work at Goldman Sachs was over.

*****

Now begins the great test. Has COVID-19 transformed the office-based working world forever? Or will the much-ballyhooed transformation sputter, defying the pundits and pollsters? A recent poll finds that only 3% of white-collar workers want to report to the office five days a week, and many say if they’re required to do so, they’ll quit. In today’s labor market, can the unrepentant Goldman model—requiring many workers in the office not five days a week, but often six or seven—survive?

Some argue that Goldman isn’t quite the talent magnet it once was and can’t continue demanding so much from its recruits. “Being an M&A banker is no longer an alpha male thing,” says William D. Cohan, a journalist, author, and former Wall Street investment banker whose books include Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World. “The alphas have gone on to private equity or tech.” Among the Harvard Business School’s class of 2021, 23% went into consulting, 19% into technology, 14% into private equity, 8% into hedge funds, 7% into venture capital, and just 4% into Goldman’s industry, investment banking.

One could argue that those numbers are misleading because going from business school to investment banking is yesterday’s career model. “Back when I graduated from Columbia Business School in 1987, literally it was either investment banking or consulting,” says Cohan. “Now if you’re getting an MBA and going to be an associate on Wall Street, that’s considered a bit of a failure.” Much better is that “you graduate from college, get an analyst job on Wall Street, and then get whisked away as quickly as possible by the private equity firms.”

That only adds to the pressure Goldman is facing to continue attracting the best candidates coming out of undergrad. But the competition is fierce. The employer branding firm Universum’s latest survey of over a million students worldwide, including undergraduates, finds that the most ambitious students favor investment banking; Morgan Stanley, UBS, and Goldman are virtually tied for the top score.

But even if Goldman continues to draw the supersmart go-getters it prizes, it could pay a price in other ways. “If you really believe in diversity, our data tells us that the diverse talent—Black, Latinx, Asian, women—all have a higher preference to be at home,” says Deborah Lovich, a senior partner at Boston Consulting Group. “So if there’s another employer that will meet that preference, you’re going to be left out.” That’s bad news, she says, because “diversity is key to better product and innovation. There’s tons of data on it. You’ll be at a loss.” Her bottom-line view: “The challenge is not, Do we bring everyone back?” Rather, it’s “getting hybrid work to work really effectively.”

David Solomon thinks such worries are simplistic or ill-informed. He has made diversifying the workforce a priority, for example insisting that incoming classes of analysts be at least 50% female; Goldman hit the target for the first time in 2020, with 55%. The firm now publishes data on minority representation, as do the other big banks. Goldman’s numbers are in the middle of the pack; Black employees were 6.8% of the firm’s U.S. workforce in 2020 (most recent available data), half the Black percentage of the U.S. population. But the numbers are rising, and increasing them is a factor in managers’ bonuses.

As for attracting the best and brightest, Solomon believes the popular framing of a Wall Street vs. Big Tech competition is “a vast oversimplification.” Each industry attracts a wide range of applicants for a wide range of jobs. “Somebody that goes to work for Facebook as a software engineer is a completely different person with completely different goals and ambitions than someone that goes to Facebook to sell advertising,” he says. “Someone that comes to Goldman Sachs to be an investment banker or trader is different from somebody that comes to Goldman Sachs to be a software engineer.” Goldman doesn’t have to beat every employer for every job opening; it just needs to get the right people in the right jobs, and Solomon believes he can still do that.

More broadly, it may well be that only 3% of the white-collar workforce want to work full-time in an office, but Goldman needs to attract only a tiny fraction of that pool. Women and minorities are more likely to prefer remote work, but again, within the averages Solomon may be able to find the special few he wants.

One more subtlety often overlooked: On any given day, many Goldman employees are working remotely. The culture has always accommodated employees who need to stay home for unexpected reasons. The company offers a generous family leave policy. In the hierarchy’s upper reaches, managers travel heavily to visit clients, and they work from the road. When Nathan Risser burned out and told his bosses he needed time off, he says, they agreed immediately and told him to stay out as long as he needed. “Your bosses are very demanding,” he tells Fortune, “but when you put in a request for something”—he snaps his fingers—“it’s granted.” Life at Goldman is lived in “a culture that allows people to deal with what they have to deal with,” says Solomon. “But that’s very different from having the latitude to wake up and say, ‘You know, it’s raining. I don’t feel like going to work.’”

The unanswered question is whether enough of today’s and tomorrow’s best young people will accept that culture. An executive in another industry recalls that as a young Goldman employee 15 years ago, “I at least had the question in my mind, Do I need to be here doing this work? And that was with the technology tools we had at the time.”

A sharp generational fault line may be widening. Daily occupancy at Goldman HQ was recently at 60% to 70%—better than the 50% on back-to-the-office day but not back to normal even accounting for normal travel and other factors. A retired senior partner observes, “Not just at Goldman but at all the firms, the biggest resistance to coming into the office is coming from the most junior people. It’s really quite remarkable. And the senior ones don’t like it.”

Solomon is jarringly out of step with corporate America. Working from home is the new normal, office towers are being converted to condos, and homes in leafy suburbs are priced like palaces. But Solomon isn’t bound by broad trends; he’s focused on Goldman, ever unique. “I just don’t think the way we work in our business is that different than it was five years ago,” he says, “and I don’t think it will be different five years from now.”

Like any good Wall Street banker, he’s willing to bet against the crowd. Much is riding on whether he’s right.