在底特律,一条公路的两侧展现了汽车行业的过去与未来。

在罗格河,福特汽车公司(Ford Motor Co.)大规模生产A型车的大型工厂,已有百年历史。在这个占地600英亩的园区内,这座工厂是最忙碌的工厂之一,生产出了美国过去四十年最畅销的汽油驱动F-150皮卡车,这也是福特利润最高的车型。

然而,在街对面的罗格电动汽车中心(Rouge Electric Vehicle Center),则是新时代的标志。4月末,首批电池驱动F-150 Lightning电动汽车在该工厂下线,这款汽车将成为底特律制造的第一款重量级电动汽车。

福特汽车的过去与未来在这里交相辉映,不仅代表了该公司在电动汽车领域500亿美元的豪赌,也展现了全球汽车行业的格局。新建成的罗格工厂是检验美国消费者的一块试金石,Lightning车型则是福特自发布Model T以来最重要的一次新车发布。福特希望通过这款车型,证明它有能力向基于软件的、电池驱动电动汽车转型,能够成功生产和销售不同于传统卡车、更像是iPhone手机但可载重10,000磅的汽车。

福特CEO吉姆·法利告诉《财富》杂志:“这让我们有机会重新定义公司在十几二十岁的年轻人心目中的形象,就像我们之前推出Model T一样。”

底特律的三家老牌汽车厂商通用汽车(General Motors)、福特和拥有克莱斯勒(Chrysler)的欧洲合资公司Stellantis都在重新调整公司的业务。这三家公司共投资了1,200亿美元,将在2030年前生产数百万辆电动汽车。这些投资的力度远远超过了汽车行业以往遭遇的挫折,正在重新改造汽车城,对当地居民的思维、工作和生活产生了颠覆性影响。

所谓的改造,一方面是字面意义上的重建,比如底特律三巨头为适应电动汽车时代对工厂进行的改造。有些是在公司层面,比如三巨头大力开发和收购软件业务和电动汽车电池技术等。然而,难度最大的改造在于人力资源方面,因为汽车行业在密歇根州雇佣了29万人,而电气化转型正在对该行业产生连锁反应。

底特律大多数人都承认但很少有人愿意讨论的一个话题是,即使转型成功,也意味着汽车行业的传统就业岗位将越来越少。推动变革的力量来自两个方面:电池组的零部件远少于内燃机(ICE),因此电动汽车装配线需要的工时减少了约30%。正如法利所说:“制造业岗位将从生产燃油汽车转变为生产数字化产品。”

与此同时,电动汽车的电气化传动系统需要电气工程师、软件开发人员和各种技术人员。电动汽车使用的日益复杂的软件系统,还需要大量程序员、研究人员和设计师。简而言之,行业的重心正在从装配线向计算机工作台转变。

密歇根州政府在最佳情景下预测,电气化生态系统从电池生产和回收到维护和充电网络,将创造30万个新工作岗位。但某些现有就业岗位注定会消失。密歇根大学(University of Michigan)劳动经济学家唐恩·格里姆斯表示,未来几年,美国汽车工厂的就业岗位将减少约三分之一。密歇根州政府官员估计,行业巨变将影响当地60%的汽车行业劳动力,有17万工人需要学习新技能,或者到其他行业就业。

福特和通用汽车分别在密歇根州雇佣了5万人和5.2万人,远超过其他美国公司,他们的决定将重新塑造整个劳动力队伍。随着这些公司的数字化水平越来越高,他们将面临一个不同的两难境地:他们要相互竞争,要与其他传统厂商争夺人才,还要面对电动汽车行业的先锋特斯拉(Tesla)以及其他科技驱动行业的竞争,这些行业同样需要大量程序员和工程师。

玛丽·巴拉对于人才争夺战持乐观态度。通用汽车CEO玛丽·巴拉在位于密歇根州沃伦的通用汽车全球技术中心(GM Global Technical Center)接受了《财富》杂志采访,这是一栋中世纪风格的现代办公大楼。她表示:“我们在招聘时发现,人们希望为一家能够改变世界的公司工作。他们希望雇主与自己有共同的价值观。在我们宣布2035年前轻型汽车全部电气化之后,求职者人数显著增加。”

但这些求职者将要经历一段困难时期。虽然传统汽车厂商的投资力度惊人,也制定了令人瞠目的生产目标,但这些公司的电气化未来并非万无一失。目前,底特律加快生产电动汽车,主要是受到政府要求的推动,而不是源自消费者需求:2021年,美国销售的1,500万辆新车,只有4%是电动汽车,尽管电动汽车的占比正在快速增长。供应链问题,包括半导体和电池原材料短缺、通货膨胀,俄乌冲突造成的破坏以及中国因为新冠疫情导致工厂停工等原因,使电动汽车的物流和资金变得更加困难。

在这种不确定性当中,唯一可以确定的是,底特律作为美国的汽车城,需要做好准备,迎接这座城市历史上最声势浩大的转型。

****

多年来,福特和通用汽车一直在试验电动汽车,但这两家公司最近正在加快这方面的投入,投入的力度再怎么夸张也不为过。巴拉在2021年1月宣布,通用汽车将在2035年前逐步停产内燃机汽车。福特虽然没有承诺彻底停止生产内燃机汽车,但计划在2030年前电动汽车的销售额占比达到50%。今年3月,福特正式启动转型,将电动汽车业务与内燃机业务Ford Blue拆分,现在更名为Ford Model e。华尔街对于福特的决定表示欢迎,认为Blue部门强大的现金流能够支持福特扩大电动汽车业务。

这种用内燃机汽车的利润支持零排放未来的策略,已经帮助两家公司全面改造其实物资产。这种变化在底特律的工厂表现得最为突出,两家公司在底特律关闭旧工厂,开设新工厂,并将生产汽油引擎汽车的工厂改造成电动汽车工厂。这些改造不动产的决定产生了深远影响,比如城市用水的税基发生变化,以及科尼岛24小时餐厅变得火爆等。两班倒和三班倒工人下班后会到这些餐厅用餐。

其中最引人关注的改造是通用汽车的“零号工厂”(Factory Zero)。通用汽车对位于哈姆特拉米克有近40年历史的工厂改造后选用了这个新名称。该公司投入22亿美元对该工厂进行改造,用于生产电动汽车,包括雪佛兰(Chevrolet)Silverado和GMC悍马(Hummer)皮卡等;美国总统拜登在11月参加了工厂的开工仪式,底特律市长迈克·达根3月在这座工厂发表了市情咨文。福特投资7亿美元改造Rouge工厂,用于生产Lightning;投资1.85亿美元在底特律机场附近新建了一座电池实验室Ford Ion Park;投资2.5亿美元改造小型地方工厂,以增加Lightning的产能。

巴拉认为,这种制造基础设施使底特律在电气化竞赛中占据了独特优势。她表示,即使软件成为汽车的核心部分,“我们依旧对于制造企业的身份非常自豪。随着其他公司进入这个行业,他们开始认识到制造业务的艰难。”

密歇根州汽车行业协会MICHauto的执行董事格伦·史蒂文斯也认同这种观点:“实际上我们有一种优势,但多年来我们一直认为这种优势是理所当然的。”在汽车和交通工程与制造领域,没有一个地方的产业密集程度能够超过密歇根州。”底特律汽车厂商的领导者们认为,改造当地的产业集群,比从零开始更容易。

通用汽车和福特还在围绕电动汽车平台开发更多新业务。例如,通用汽车内部的创新实验室(Innovation Lab)已经孵化了一家电动商用快递车制造商BrightDrop,该公司已经获得了联邦快递(FedEx)和沃尔玛(Walmart)的厢式货车生产合同;BrightDrop目前正在帕洛阿尔托、底特律和亚特兰大招聘数百名工程师、软件开发人员和产品设计师。通用汽车还预计自动驾驶汽车公司Cruise明年将在零号工厂生产第一款商用车型Cruise Origin班车:通用汽车认为到2030年,Cruise在网约车和汽车租赁公司的年销售额可能达到500亿美元。通用汽车是Cruise的大股东。

在采访过程中,巴拉生动介绍了通用汽车正在开发的基于云的订阅软件服务Ultifi。Ultifi将在明年发布,有望成为通用汽车各车型的操作系统,可以像智能手机(和特斯拉)一样经常升级:通用汽车表示,到2030年,该项服务每年可创收250亿美元。订阅Ultifi的用户不需要买新车也可以下载各种汽车功能,目前这些功能仍在设计阶段,例如用摄像头通过面部识别启动汽车,或者与车主的智能家居应用沟通等。Ultifi还可以与第三方应用互动;而且随着软件控制车内的功能越来越多,它将是高效修复任何漏洞的一种方式。

巴拉表示:“我们的理念是,在你拥有车辆之后,它会变得越来越好。两三年后,我可能获得一项买车时还不存在的功能,这将重新定义我们的业务。”

****

当然,重新定义业务也意味着重新定义劳动力:有一个不可避免的问题是改造后的工厂需要怎样的劳动力,以及工厂能提供怎样的工资水平。比如生产一辆福特野马所需要的技能,与制造一台车轮上的iPhone手机所需要的技能截然不同。

有人认为底特律的传统汽车装配线岗位将逐渐消失,取而代之的是人数更少但更精通技术的劳动力,但三家传统汽车厂商很快就打消了这个念头。Stellantis位于阿姆斯特丹的CEO卡洛斯·塔瓦雷斯对《财富》杂志表示:“第一个重要的预期是,我们不应该害怕改变。汽车装配线肯定会有一些改变,但改变并不可怕。”

通用汽车用零号工厂反驳了人们对于裁员的恐慌。零号工厂的执行董事吉姆·奎克表示:“有人认为我们正在缩小规模,电气化意味着就业岗位减少,但这并不是我们所看到的情形。我们已经宣布工厂将有约2,200多个就业岗位。我们很长时间以来在这里都没有如此多的就业岗位。”大多数岗位都有工会支持:美国汽车工人联盟(United Auto Workers)已经在向底特律三巨头施压,以保证工会的成员不会在这场转型中被淘汰。

尽管如此,有“模拟”背景的工人,生产电动汽车传动系统和电池,需要接受再培训。在通用汽车的奥莱恩装配厂,1,000多名工人在2020年经过重新培训,全部从生产汽油引擎汽车,转岗为生产雪佛兰Bolt电动汽车。(通用汽车表示,工厂开始生产电动皮卡车时,工人人数将增加两倍以上。)零号工厂的许多员工也接受了再培训。巴拉认为,留住原有工人除了保障就业,还有其他好处,例如工厂可以此为契机,改造企业文化,使工人凭借自身的技能而不是学历获得发展机会。她表示:“我认为这将给其他人带来发展机会,他们认为四年本科学历并不能代表一切。”

还有许多公共和私人利益相关者也在围绕电动汽车技能开发新的教育课程。密歇根州向开发电动汽车职业认证课程的机构提供资助,包括经销商技术人员和充电站的电工等。

就连硅谷巨头也参与了进来。去年夏天,苹果(Apple)在底特律建立了一所开发者学院;该学院为第一批100名学员提供的10个月免费编程和应用开发培训刚刚结束。这批学员的年龄在18至60岁之间。谷歌(Google)计划从明年开始在底特律开办免费编程课,帮助高中生为从事高科技岗位做好准备。

已经三次连任的底特律市长达根一直在努力游说,希望将电动汽车制造岗位留在当地。达根在市政厅11层的办公室里接受记者采访时,回想起他说服三大巨头的理由:“我告诉他们:‘我希望你们不只是在这里生产电动汽车,我还希望设计未来电动汽车和自动化汽车的创业者们,也想搬到这里。’”菲亚特克莱斯勒(Fiat Chrysler)在考虑为新吉普大切诺基(Jeep Grand Cherokee)插电式混合动力车型选址时,底特律提出安排招聘会进行招聘,并对底特律居民进行预先筛选。作为交换,菲亚特克莱斯勒承诺投资16亿美元,将麦克大街发动机综合大楼(Mack Avenue Engine Complex)改造成生产电动汽车传动系统的工厂;2021年6月工厂重新开工。

达根表示:“如果你把工厂设在底特律,当地的劳动力能为你带来巨大帮助。如果你打算在芝加哥郊区40英里的玉米地里建设工厂,工人招聘将会面临更大的挑战。”

当然,并非所有现有员工都能在电气化时代找到工作。劳动经济学家格里姆斯表示:“电动汽车革命将让许多人失业。但几乎所有技术进步都会带来这样的后果。

想想有多少秘书工作被计算机所淘汰。”尽管如此,格里姆斯补充道:“人们更换职业并搬到新的城镇生活,这确实是一项挑战,但终究是值得的。”底特律面临的长期挑战:保证再培训和技能提升能够让人们掌握继续工作所需要的技能,尽管这意味着更换职业。

****

在开展在培训的同时,汽车厂商也在努力吸引各类白领技术人员,但这并不意味着吸引他们搬到底特律

巴拉表示,通用汽车在几年前就开始用新一代软件人才取代退休人员,招聘并没有遇到太大困难。但并非所有软件人才都将来到密歇根州。通用汽车还在旧金山、特拉维夫和位于安大略省马卡姆的技术中心大力招聘。巴拉表示,位于马卡姆附近的滑铁卢大学(University of Waterloo)是“硅谷重要的人才库”。

通用汽车今年计划招聘8,000名技术工人,但将招聘地点的决定权下放给了业务部门经理。通用汽车发言人表示:“这种做法让我们可以与科技公司竞争,尤其是在软件、分析和自动驾驶汽车等领域。” MICHauto的史蒂文斯表示:“随着远程经济的兴起,面对对软件工程师的巨大需求,[汽车厂商]将变得更加灵活,就像微软(Microsoft)、谷歌或亚马逊(Amazon)一样。”

对于程序员和软件工程师们而言,底特律并非未知之地:福特和通用汽车已经在底特律雇佣了数千名开发人员,而且年轻的技术人员已经在重新塑造这座城市的形象。

如果说装配工人往往生活在斯特林高地或圣克莱尔肖尔斯的平房社区,会到中密歇根州或密歇根上半岛的小屋里过周末,软件开发者更有可能住在市区的公寓,晚上在Shelby用餐。Shelby是曾经荣获詹姆斯·比尔德基金会半决赛奖的一家鸡尾酒酒吧,原址是一家银行的地下室。

汽车厂商也在开发协作空间,吸引喜欢冒险的STEM人才。福特将在2026年前在美国各地投入5.25亿美元用于劳动力开发,其中知名度最高的是在迪尔伯恩兴建的研究与工程设计中心(Research & Engineering Center),占地200万平方英尺,到2025年改造完成后,将对20,000名福特设计师、工程师和产品开发者提供培训,他们是电动汽车革命的主力。

有些空间是多家公司合作的成果。在一条市中心主干道沿线,有一座不起眼的停车场,这里是底特律智能停车实验室(Detroit Smart Parking Lab)的所在地。这是由福特、零部件供应商博世(Bosch)、密西根州政府以及快速贷款公司(Quicken Loans)联合创始人丹·吉尔伯特的商业地产公司Bedrock联合成立的一个实验室。

该实验室由美国移动中心(American Center for Mobility)负责运营,是从充电站到云服务等各种汽车技术的联合试验场。参与试验的公司既有Enterprise Rent-A-Car,也有专注于电动汽车无线充电的初创公司Hevo。美国移动中心总裁兼CEO鲁本·萨卡尔表示:“我们看到许多项目都只代表了一片拼图。而通过这个实验室,不同领域可以进行协作。”

或许最能体现这种跨领域合作的是密歇根中央车站(Michigan Central Station)。自从1988年美国铁路公司(Amtrak)的最后一列火车从这里出发以来,密歇根中央车站一直被作为底特律城市衰败的典型例子。在底特律考克镇社区,曾经宏伟的古典建筑风格的密歇根中央车站,依旧被铁丝网包围,阻挡着蓄意破坏者和非法占据者闯入。

但福特投资9.5亿美元,计划将这座车站开发成交通科技合作中心。这栋综合建筑定于明年启用,将有福特的大批骨干技术人员入驻,还为其他公司提供了办公空间,例如谷歌和自动驾驶汽车公司Argo AI等。创新人员将在这里开发、测试和发布与自动驾驶汽车、公共交通、智能公路和电动汽车基础设施等有关的技术。福特在园区安排的5,000名员工中,约一半将是现有员工,这在创新前沿与母公司之间构建了一条通道。

****

很长时间以来,底特律都被作为美国汽车行业的代名词,因此人们很容易忘记,美国汽车业国内的产量大部分并非来自底特律。三大巨头的传统汽车生产业务大多位于密歇根州以外,电动汽车业务同样如此。

通用汽车投资20亿美元,用于对位于田纳西州斯普林希尔的工厂进行改造。该工厂依旧是通用汽车在北美最大的工厂。改造之后,该工厂将生产各种电动汽车,包括凯迪拉克(Cadillac)品牌旗下的第一款电池电动汽车Lyriq。但这与福特和韩国SK Innovation公司在田纳西州和肯塔基州的114亿美元投资相比,只是小巫见大巫:位于田纳西州斯坦顿的蓝瓦城工厂将生产F系列电动皮卡和先进的电池,再加上位于肯塔基州格伦代尔的两座电池工厂,将创造11,000个就业岗位。

事实上,福特和通用汽车的日益全球化,已经促使一些地方官员开始质疑,为了留住汽车工人和吸引技术人才所花费的纳税人的钱,是否可以更好地用于其他领域,例如基础设施和公共教育等。(巴拉在接受《财富》杂志采访时强调,底特律饱受指责的学校体系是阻碍家庭搬到这里的障碍之一。)

与此同时,与20世纪相比,密歇根和底特律对于汽车行业的依赖有所减少。物流、金融、医疗和IT行业都在当地带来了稳定的就业增长。虽然底特律的失业率为10%左右,依旧远高于全国平均水平,但与大衰退期间相比,当地经济已经有明显好转。通用汽车、克莱斯勒和底特律市都在大衰退期间宣布破产。

简而言之,底特律不会上演王者归来的桥段。在电动汽车转型的过程中,底特律市的筹码是质量而不是数量:福特、通用汽车和地方官员不见得希望在这里生产更多汽车,但他们希望汽车城的工人依旧在电动汽车创新的核心,参与设计、连接和自动驾驶等领域。

福特CEO法利表示:“几十年来,底特律这座城市一直在努力重新定义自己的身份。现在我们开始找到属于自己的魔力。” 这种魔力在以电动汽车为主的零号工厂和停车实验室中显而易见,底特律似乎在这些地方爆发出新的能量。 明年,在底特律市中心将会展现出这种能量。在密歇根大街的一条支线上,当地官员将宣布启用美国第一条公共电气化公路。这条公路由以色列公司Electreon和密歇根州交通部联合开发,公路下方的基础设施将为在路上行驶、停靠或等待的电动汽车无线充电。在这条公路的不远处,就是底特律100多年前推出美国第一个三色四向交通灯的十字路口,它可能是底特律未来与历史的另外一个交汇点。

****

押注电动汽车

美国三大汽车厂商、《财富》500强福特、通用汽车和克莱斯勒(已被阿姆斯特丹的Stellantis公司收购),共承诺在未来几年投资超过1,200亿美元,将更多产品线转变为电动汽车。以下是各家公司的投入。

福特汽车

承诺:

到2030年50%的销售收入来自电动汽车

投资:

到2026年在电动汽车工厂、软件和培训方面投资500亿美元

策略:

福特的重点首先是将其畅销品牌电气化,尤其是F-150 Lightning皮卡车,其汽油版四十年来持续畅销。

早期主要电动汽车型号:

F-150 Lightning、Mustang Mach-E SUV和E-Transit商用货车(目前均已上市)。

通用汽车

承诺:

到2035年全球100%的销售收入来自电动汽车

投资:

到2025年在电动汽车和自动驾驶汽车技术方面投资350亿美元

策略:

通用汽车计划到2025年在全球发布30款新电动汽车,几乎全部为新型号,而不是旧型号的升级版。

早期主要电动汽车型号:

凯迪拉克Lyriq豪华轿车和GMC悍马皮卡车(现已上市);悍马SUV和雪佛兰Silverado皮卡车(2023年)。

STELLANTIS

承诺:

到2030年欧洲100%的销售收入和北美洲50%的销售收入来自电动汽车

投资:

到2025年在电气化、软件和技术方面投资355亿美元。

策略:

到目前为止,Stellantis在北美洲的业务重点是研发畅销车型的插电式混合动力版本,但计划发布至少25款新电动汽车品牌。

早期主要电动汽车型号:

克莱斯勒Pacifica和吉普大切诺基4xe(现已上市);吉普Wagoneer 4xe(今年晚些时候)。

(财富中文网)

译者:Biz

在底特律,一条公路的两侧展现了汽车行业的过去与未来。

在罗格河,福特汽车公司(Ford Motor Co.)大规模生产A型车的大型工厂,已有百年历史。在这个占地600英亩的园区内,这座工厂是最忙碌的工厂之一,生产出了美国过去四十年最畅销的汽油驱动F-150皮卡车,这也是福特利润最高的车型。

然而,在街对面的罗格电动汽车中心(Rouge Electric Vehicle Center),则是新时代的标志。4月末,首批电池驱动F-150 Lightning电动汽车在该工厂下线,这款汽车将成为底特律制造的第一款重量级电动汽车。

福特汽车的过去与未来在这里交相辉映,不仅代表了该公司在电动汽车领域500亿美元的豪赌,也展现了全球汽车行业的格局。新建成的罗格工厂是检验美国消费者的一块试金石,Lightning车型则是福特自发布Model T以来最重要的一次新车发布。福特希望通过这款车型,证明它有能力向基于软件的、电池驱动电动汽车转型,能够成功生产和销售不同于传统卡车、更像是iPhone手机但可载重10,000磅的汽车。

福特CEO吉姆·法利告诉《财富》杂志:“这让我们有机会重新定义公司在十几二十岁的年轻人心目中的形象,就像我们之前推出Model T一样。”

底特律的三家老牌汽车厂商通用汽车(General Motors)、福特和拥有克莱斯勒(Chrysler)的欧洲合资公司Stellantis都在重新调整公司的业务。这三家公司共投资了1,200亿美元,将在2030年前生产数百万辆电动汽车。这些投资的力度远远超过了汽车行业以往遭遇的挫折,正在重新改造汽车城,对当地居民的思维、工作和生活产生了颠覆性影响。

所谓的改造,一方面是字面意义上的重建,比如底特律三巨头为适应电动汽车时代对工厂进行的改造。有些是在公司层面,比如三巨头大力开发和收购软件业务和电动汽车电池技术等。然而,难度最大的改造在于人力资源方面,因为汽车行业在密歇根州雇佣了29万人,而电气化转型正在对该行业产生连锁反应。

底特律大多数人都承认但很少有人愿意讨论的一个话题是,即使转型成功,也意味着汽车行业的传统就业岗位将越来越少。推动变革的力量来自两个方面:电池组的零部件远少于内燃机(ICE),因此电动汽车装配线需要的工时减少了约30%。正如法利所说:“制造业岗位将从生产燃油汽车转变为生产数字化产品。”

与此同时,电动汽车的电气化传动系统需要电气工程师、软件开发人员和各种技术人员。电动汽车使用的日益复杂的软件系统,还需要大量程序员、研究人员和设计师。简而言之,行业的重心正在从装配线向计算机工作台转变。

密歇根州政府在最佳情景下预测,电气化生态系统从电池生产和回收到维护和充电网络,将创造30万个新工作岗位。但某些现有就业岗位注定会消失。密歇根大学(University of Michigan)劳动经济学家唐恩·格里姆斯表示,未来几年,美国汽车工厂的就业岗位将减少约三分之一。密歇根州政府官员估计,行业巨变将影响当地60%的汽车行业劳动力,有17万工人需要学习新技能,或者到其他行业就业。

福特和通用汽车分别在密歇根州雇佣了5万人和5.2万人,远超过其他美国公司,他们的决定将重新塑造整个劳动力队伍。随着这些公司的数字化水平越来越高,他们将面临一个不同的两难境地:他们要相互竞争,要与其他传统厂商争夺人才,还要面对电动汽车行业的先锋特斯拉(Tesla)以及其他科技驱动行业的竞争,这些行业同样需要大量程序员和工程师。

玛丽·巴拉对于人才争夺战持乐观态度。通用汽车CEO玛丽·巴拉在位于密歇根州沃伦的通用汽车全球技术中心(GM Global Technical Center)接受了《财富》杂志采访,这是一栋中世纪风格的现代办公大楼。她表示:“我们在招聘时发现,人们希望为一家能够改变世界的公司工作。他们希望雇主与自己有共同的价值观。在我们宣布2035年前轻型汽车全部电气化之后,求职者人数显著增加。”

但这些求职者将要经历一段困难时期。虽然传统汽车厂商的投资力度惊人,也制定了令人瞠目的生产目标,但这些公司的电气化未来并非万无一失。目前,底特律加快生产电动汽车,主要是受到政府要求的推动,而不是源自消费者需求:2021年,美国销售的1,500万辆新车,只有4%是电动汽车,尽管电动汽车的占比正在快速增长。供应链问题,包括半导体和电池原材料短缺、通货膨胀,俄乌冲突造成的破坏以及中国因为新冠疫情导致工厂停工等原因,使电动汽车的物流和资金变得更加困难。

在这种不确定性当中,唯一可以确定的是,底特律作为美国的汽车城,需要做好准备,迎接这座城市历史上最声势浩大的转型。

****

多年来,福特和通用汽车一直在试验电动汽车,但这两家公司最近正在加快这方面的投入,投入的力度再怎么夸张也不为过。巴拉在2021年1月宣布,通用汽车将在2035年前逐步停产内燃机汽车。福特虽然没有承诺彻底停止生产内燃机汽车,但计划在2030年前电动汽车的销售额占比达到50%。今年3月,福特正式启动转型,将电动汽车业务与内燃机业务Ford Blue拆分,现在更名为Ford Model e。华尔街对于福特的决定表示欢迎,认为Blue部门强大的现金流能够支持福特扩大电动汽车业务。

这种用内燃机汽车的利润支持零排放未来的策略,已经帮助两家公司全面改造其实物资产。这种变化在底特律的工厂表现得最为突出,两家公司在底特律关闭旧工厂,开设新工厂,并将生产汽油引擎汽车的工厂改造成电动汽车工厂。这些改造不动产的决定产生了深远影响,比如城市用水的税基发生变化,以及科尼岛24小时餐厅变得火爆等。两班倒和三班倒工人下班后会到这些餐厅用餐。

其中最引人关注的改造是通用汽车的“零号工厂”(Factory Zero)。通用汽车对位于哈姆特拉米克有近40年历史的工厂改造后选用了这个新名称。该公司投入22亿美元对该工厂进行改造,用于生产电动汽车,包括雪佛兰(Chevrolet)Silverado和GMC悍马(Hummer)皮卡等;美国总统拜登在11月参加了工厂的开工仪式,底特律市长迈克·达根3月在这座工厂发表了市情咨文。福特投资7亿美元改造Rouge工厂,用于生产Lightning;投资1.85亿美元在底特律机场附近新建了一座电池实验室Ford Ion Park;投资2.5亿美元改造小型地方工厂,以增加Lightning的产能。

巴拉认为,这种制造基础设施使底特律在电气化竞赛中占据了独特优势。她表示,即使软件成为汽车的核心部分,“我们依旧对于制造企业的身份非常自豪。随着其他公司进入这个行业,他们开始认识到制造业务的艰难。”

密歇根州汽车行业协会MICHauto的执行董事格伦·史蒂文斯也认同这种观点:“实际上我们有一种优势,但多年来我们一直认为这种优势是理所当然的。”在汽车和交通工程与制造领域,没有一个地方的产业密集程度能够超过密歇根州。”底特律汽车厂商的领导者们认为,改造当地的产业集群,比从零开始更容易。

通用汽车和福特还在围绕电动汽车平台开发更多新业务。例如,通用汽车内部的创新实验室(Innovation Lab)已经孵化了一家电动商用快递车制造商BrightDrop,该公司已经获得了联邦快递(FedEx)和沃尔玛(Walmart)的厢式货车生产合同;BrightDrop目前正在帕洛阿尔托、底特律和亚特兰大招聘数百名工程师、软件开发人员和产品设计师。通用汽车还预计自动驾驶汽车公司Cruise明年将在零号工厂生产第一款商用车型Cruise Origin班车:通用汽车认为到2030年,Cruise在网约车和汽车租赁公司的年销售额可能达到500亿美元。通用汽车是Cruise的大股东。

在采访过程中,巴拉生动介绍了通用汽车正在开发的基于云的订阅软件服务Ultifi。Ultifi将在明年发布,有望成为通用汽车各车型的操作系统,可以像智能手机(和特斯拉)一样经常升级:通用汽车表示,到2030年,该项服务每年可创收250亿美元。订阅Ultifi的用户不需要买新车也可以下载各种汽车功能,目前这些功能仍在设计阶段,例如用摄像头通过面部识别启动汽车,或者与车主的智能家居应用沟通等。Ultifi还可以与第三方应用互动;而且随着软件控制车内的功能越来越多,它将是高效修复任何漏洞的一种方式。

巴拉表示:“我们的理念是,在你拥有车辆之后,它会变得越来越好。两三年后,我可能获得一项买车时还不存在的功能,这将重新定义我们的业务。”

****

当然,重新定义业务也意味着重新定义劳动力:有一个不可避免的问题是改造后的工厂需要怎样的劳动力,以及工厂能提供怎样的工资水平。比如生产一辆福特野马所需要的技能,与制造一台车轮上的iPhone手机所需要的技能截然不同。

有人认为底特律的传统汽车装配线岗位将逐渐消失,取而代之的是人数更少但更精通技术的劳动力,但三家传统汽车厂商很快就打消了这个念头。Stellantis位于阿姆斯特丹的CEO卡洛斯·塔瓦雷斯对《财富》杂志表示:“第一个重要的预期是,我们不应该害怕改变。汽车装配线肯定会有一些改变,但改变并不可怕。”

通用汽车用零号工厂反驳了人们对于裁员的恐慌。零号工厂的执行董事吉姆·奎克表示:“有人认为我们正在缩小规模,电气化意味着就业岗位减少,但这并不是我们所看到的情形。我们已经宣布工厂将有约2,200多个就业岗位。我们很长时间以来在这里都没有如此多的就业岗位。”大多数岗位都有工会支持:美国汽车工人联盟(United Auto Workers)已经在向底特律三巨头施压,以保证工会的成员不会在这场转型中被淘汰。

尽管如此,有“模拟”背景的工人,生产电动汽车传动系统和电池,需要接受再培训。在通用汽车的奥莱恩装配厂,1,000多名工人在2020年经过重新培训,全部从生产汽油引擎汽车,转岗为生产雪佛兰Bolt电动汽车。(通用汽车表示,工厂开始生产电动皮卡车时,工人人数将增加两倍以上。)零号工厂的许多员工也接受了再培训。巴拉认为,留住原有工人除了保障就业,还有其他好处,例如工厂可以此为契机,改造企业文化,使工人凭借自身的技能而不是学历获得发展机会。她表示:“我认为这将给其他人带来发展机会,他们认为四年本科学历并不能代表一切。”

还有许多公共和私人利益相关者也在围绕电动汽车技能开发新的教育课程。密歇根州向开发电动汽车职业认证课程的机构提供资助,包括经销商技术人员和充电站的电工等。

就连硅谷巨头也参与了进来。去年夏天,苹果(Apple)在底特律建立了一所开发者学院;该学院为第一批100名学员提供的10个月免费编程和应用开发培训刚刚结束。这批学员的年龄在18至60岁之间。谷歌(Google)计划从明年开始在底特律开办免费编程课,帮助高中生为从事高科技岗位做好准备。

已经三次连任的底特律市长达根一直在努力游说,希望将电动汽车制造岗位留在当地。达根在市政厅11层的办公室里接受记者采访时,回想起他说服三大巨头的理由:“我告诉他们:‘我希望你们不只是在这里生产电动汽车,我还希望设计未来电动汽车和自动化汽车的创业者们,也想搬到这里。’”菲亚特克莱斯勒(Fiat Chrysler)在考虑为新吉普大切诺基(Jeep Grand Cherokee)插电式混合动力车型选址时,底特律提出安排招聘会进行招聘,并对底特律居民进行预先筛选。作为交换,菲亚特克莱斯勒承诺投资16亿美元,将麦克大街发动机综合大楼(Mack Avenue Engine Complex)改造成生产电动汽车传动系统的工厂;2021年6月工厂重新开工。

达根表示:“如果你把工厂设在底特律,当地的劳动力能为你带来巨大帮助。如果你打算在芝加哥郊区40英里的玉米地里建设工厂,工人招聘将会面临更大的挑战。”

当然,并非所有现有员工都能在电气化时代找到工作。劳动经济学家格里姆斯表示:“电动汽车革命将让许多人失业。但几乎所有技术进步都会带来这样的后果。

想想有多少秘书工作被计算机所淘汰。”尽管如此,格里姆斯补充道:“人们更换职业并搬到新的城镇生活,这确实是一项挑战,但终究是值得的。”底特律面临的长期挑战:保证再培训和技能提升能够让人们掌握继续工作所需要的技能,尽管这意味着更换职业。

****

在开展在培训的同时,汽车厂商也在努力吸引各类白领技术人员,但这并不意味着吸引他们搬到底特律。巴拉表示,通用汽车在几年前就开始用新一代软件人才取代退休人员,招聘并没有遇到太大困难。但并非所有软件人才都将来到密歇根州。通用汽车还在旧金山、特拉维夫和位于安大略省马卡姆的技术中心大力招聘。巴拉表示,位于马卡姆附近的滑铁卢大学(University of Waterloo)是“硅谷重要的人才库”。

通用汽车今年计划招聘8,000名技术工人,但将招聘地点的决定权下放给了业务部门经理。通用汽车发言人表示:“这种做法让我们可以与科技公司竞争,尤其是在软件、分析和自动驾驶汽车等领域。” MICHauto的史蒂文斯表示:“随着远程经济的兴起,面对对软件工程师的巨大需求,[汽车厂商]将变得更加灵活,就像微软(Microsoft)、谷歌或亚马逊(Amazon)一样。”

对于程序员和软件工程师们而言,底特律并非未知之地:福特和通用汽车已经在底特律雇佣了数千名开发人员,而且年轻的技术人员已经在重新塑造这座城市的形象。

如果说装配工人往往生活在斯特林高地或圣克莱尔肖尔斯的平房社区,会到中密歇根州或密歇根上半岛的小屋里过周末,软件开发者更有可能住在市区的公寓,晚上在Shelby用餐。Shelby是曾经荣获詹姆斯·比尔德基金会半决赛奖的一家鸡尾酒酒吧,原址是一家银行的地下室。

汽车厂商也在开发协作空间,吸引喜欢冒险的STEM人才。福特将在2026年前在美国各地投入5.25亿美元用于劳动力开发,其中知名度最高的是在迪尔伯恩兴建的研究与工程设计中心(Research & Engineering Center),占地200万平方英尺,到2025年改造完成后,将对20,000名福特设计师、工程师和产品开发者提供培训,他们是电动汽车革命的主力。

有些空间是多家公司合作的成果。在一条市中心主干道沿线,有一座不起眼的停车场,这里是底特律智能停车实验室(Detroit Smart Parking Lab)的所在地。这是由福特、零部件供应商博世(Bosch)、密西根州政府以及快速贷款公司(Quicken Loans)联合创始人丹·吉尔伯特的商业地产公司Bedrock联合成立的一个实验室。

该实验室由美国移动中心(American Center for Mobility)负责运营,是从充电站到云服务等各种汽车技术的联合试验场。参与试验的公司既有Enterprise Rent-A-Car,也有专注于电动汽车无线充电的初创公司Hevo。美国移动中心总裁兼CEO鲁本·萨卡尔表示:“我们看到许多项目都只代表了一片拼图。而通过这个实验室,不同领域可以进行协作。”

或许最能体现这种跨领域合作的是密歇根中央车站(Michigan Central Station)。自从1988年美国铁路公司(Amtrak)的最后一列火车从这里出发以来,密歇根中央车站一直被作为底特律城市衰败的典型例子。在底特律考克镇社区,曾经宏伟的古典建筑风格的密歇根中央车站,依旧被铁丝网包围,阻挡着蓄意破坏者和非法占据者闯入。

但福特投资9.5亿美元,计划将这座车站开发成交通科技合作中心。这栋综合建筑定于明年启用,将有福特的大批骨干技术人员入驻,还为其他公司提供了办公空间,例如谷歌和自动驾驶汽车公司Argo AI等。创新人员将在这里开发、测试和发布与自动驾驶汽车、公共交通、智能公路和电动汽车基础设施等有关的技术。福特在园区安排的5,000名员工中,约一半将是现有员工,这在创新前沿与母公司之间构建了一条通道。

****

很长时间以来,底特律都被作为美国汽车行业的代名词,因此人们很容易忘记,美国汽车业国内的产量大部分并非来自底特律。三大巨头的传统汽车生产业务大多位于密歇根州以外,电动汽车业务同样如此。

通用汽车投资20亿美元,用于对位于田纳西州斯普林希尔的工厂进行改造。该工厂依旧是通用汽车在北美最大的工厂。改造之后,该工厂将生产各种电动汽车,包括凯迪拉克(Cadillac)品牌旗下的第一款电池电动汽车Lyriq。但这与福特和韩国SK Innovation公司在田纳西州和肯塔基州的114亿美元投资相比,只是小巫见大巫:位于田纳西州斯坦顿的蓝瓦城工厂将生产F系列电动皮卡和先进的电池,再加上位于肯塔基州格伦代尔的两座电池工厂,将创造11,000个就业岗位。

事实上,福特和通用汽车的日益全球化,已经促使一些地方官员开始质疑,为了留住汽车工人和吸引技术人才所花费的纳税人的钱,是否可以更好地用于其他领域,例如基础设施和公共教育等。(巴拉在接受《财富》杂志采访时强调,底特律饱受指责的学校体系是阻碍家庭搬到这里的障碍之一。)

与此同时,与20世纪相比,密歇根和底特律对于汽车行业的依赖有所减少。物流、金融、医疗和IT行业都在当地带来了稳定的就业增长。虽然底特律的失业率为10%左右,依旧远高于全国平均水平,但与大衰退期间相比,当地经济已经有明显好转。通用汽车、克莱斯勒和底特律市都在大衰退期间宣布破产。

简而言之,底特律不会上演王者归来的桥段。在电动汽车转型的过程中,底特律市的筹码是质量而不是数量:福特、通用汽车和地方官员不见得希望在这里生产更多汽车,但他们希望汽车城的工人依旧在电动汽车创新的核心,参与设计、连接和自动驾驶等领域。

福特CEO法利表示:“几十年来,底特律这座城市一直在努力重新定义自己的身份。现在我们开始找到属于自己的魔力。” 这种魔力在以电动汽车为主的零号工厂和停车实验室中显而易见,底特律似乎在这些地方爆发出新的能量。 明年,在底特律市中心将会展现出这种能量。在密歇根大街的一条支线上,当地官员将宣布启用美国第一条公共电气化公路。这条公路由以色列公司Electreon和密歇根州交通部联合开发,公路下方的基础设施将为在路上行驶、停靠或等待的电动汽车无线充电。在这条公路的不远处,就是底特律100多年前推出美国第一个三色四向交通灯的十字路口,它可能是底特律未来与历史的另外一个交汇点。

****

押注电动汽车

美国三大汽车厂商、《财富》500强福特、通用汽车和克莱斯勒(已被阿姆斯特丹的Stellantis公司收购),共承诺在未来几年投资超过1,200亿美元,将更多产品线转变为电动汽车。以下是各家公司的投入。

福特汽车

承诺:

到2030年50%的销售收入来自电动汽车

投资:

到2026年在电动汽车工厂、软件和培训方面投资500亿美元

策略:

福特的重点首先是将其畅销品牌电气化,尤其是F-150 Lightning皮卡车,其汽油版四十年来持续畅销。

早期主要电动汽车型号:

F-150 Lightning、Mustang Mach-E SUV和E-Transit商用货车(目前均已上市)。

通用汽车

承诺:

到2035年全球100%的销售收入来自电动汽车

投资:

到2025年在电动汽车和自动驾驶汽车技术方面投资350亿美元

策略:

通用汽车计划到2025年在全球发布30款新电动汽车,几乎全部为新型号,而不是旧型号的升级版。

早期主要电动汽车型号:

凯迪拉克Lyriq豪华轿车和GMC悍马皮卡车(现已上市);悍马SUV和雪佛兰Silverado皮卡车(2023年)。

STELLANTIS

承诺:

到2030年欧洲100%的销售收入和北美洲50%的销售收入来自电动汽车

投资:

到2025年在电气化、软件和技术方面投资355亿美元。

策略:

到目前为止,Stellantis在北美洲的业务重点是研发畅销车型的插电式混合动力版本,但计划发布至少25款新电动汽车品牌。

早期主要电动汽车型号:

克莱斯勒Pacifica和吉普大切诺基4xe(现已上市);吉普Wagoneer 4xe(今年晚些时候)。

(财富中文网)

译者:Biz

Detroit, the auto industry’s past and future face each other across an access road.

The location is Rouge River, the sprawling century-old factory complex where Ford Motor Co. made Model A’s for the masses. One of the busiest plants on the 600-acre campus churns out the gas-powered F-150 pickup, America’s bestselling vehicle for the past four decades and Ford’s most profitable model.

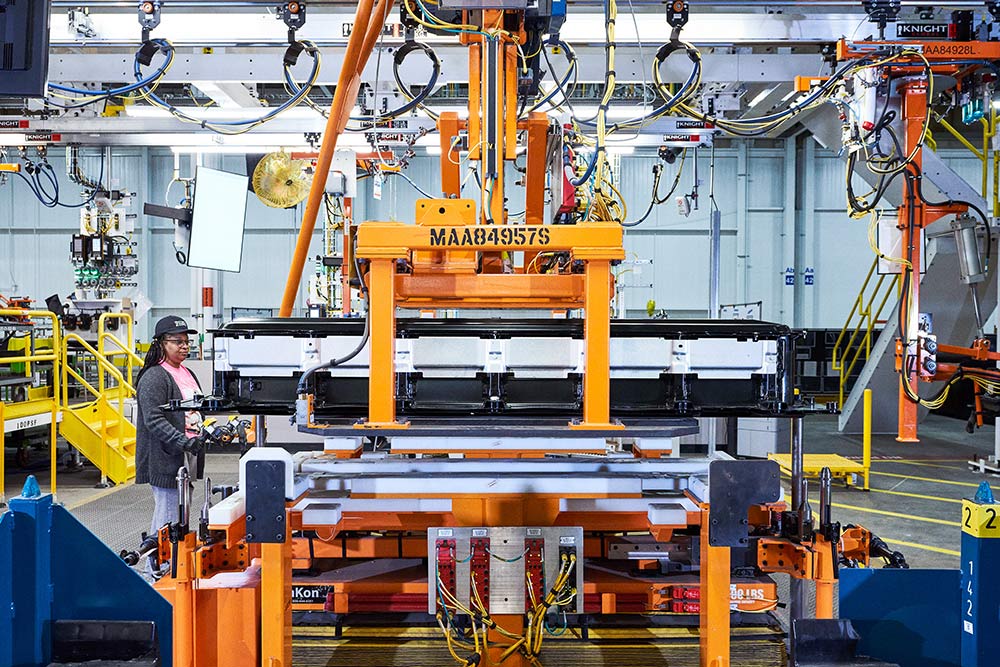

But just across the street stands a building whose signage places it in a new era: the Rouge Electric Vehicle Center. In late April, that plant produced the first batch of the Lightning battery-electric version of the F-150—a model that could be poised to become the first Detroit- made EV hit.

The juxtaposition of Ford’s past and future represents not only the company’s $50 billion bet on EVs, but the larger story playing out across the global automotive industry. The new Rouge plant is a litmus test for American consumers, and the Light- ning is Ford’s most important launch since the Model T. It’s a way for Ford to prove that it can master the transition to software-based, battery- electric vehicles—to successfully build and sell something that’s less like a workaday truck and more akin to an iPhone that can tow 10,000 pounds.

“That gives us a chance to redefine the company like we did in the teens and ’20s with the Model T,” Ford CEO Jim Farley tells Fortune.

Detroit’s three legacy automakers—General Motors; Ford; and Stellantis, the European joint venture that owns Chrysler—are all in the redefinition business. They’re investing a combined $120 billion to put millions of EVs on the road by 2030. And that collective investment—even more than the automotive industry’s past twists and turns—is remaking the Mo- tor City, creating a seismic shift in how its residents think, work, and live.

Some of this remaking is literal rebuilding, as the Detroit Three repurpose factories for the EV era. Some is corporate, as they develop and acquire businesses that focus on software and EV battery tech. But the trickiest remaking is one of human resources—as the electric transition ripples through an automotive industry that employs 290,000 people in Michigan.

What most people in Detroit acknowledge, but few like to discuss, is that even a successful transition means fewer traditional jobs in the auto industry. The forces driving the change are twofold: Battery packs have fewer parts than internal combustion engines (ICEs)—so EVs require about 30% fewer hours of labor on the assembly line. As Farley puts it, “The manufacturing jobs are going to go from making oily things to digital things.”

At the same time, the electrified powertrains of EVs require electrical engineers, software developers, and all manner of technicians. And the increasingly complex software systems that EVs rely on will need their own cadres of programmers, researchers, and designers. The industry’s center of gravity, in short, is shifting from the assembly line to the computer workbench.

In its best-case scenario, Michigan’s state government forecasts the creation of up to 300,000 new jobs across the electrification ecosystem, from battery manufacturing and recycling to service and charging networks. But some existing jobs are bound to disappear. Over the next few years, the U.S. will start shedding nearly one-third of its automotive factory jobs, according to Don Grimes, a labor economist at the University of Michigan. And state officials have estimated that the overall shift could affect 60% of Michigan’s automotive workforce, putting 170,000 workers in a position where they’ll need to learn new skills—or find work in another industry.

More than any other American companies, Ford and GM—which employ 50,000 and 52,000 people in Michigan, respectively—will make the decisions that reshape that work- force. And as they become more digital, they’ll face a different dilemma: They’ll be competing for talent not only with each other and other legacy automakers, but with EV pioneer Tesla and with countless other tech-driven industries that need programmers and engineers.

Mary Barra, for one, is bullish about the talent battle. “What we’re fi when we hire is that people want to work for a company that’s going to change the world,” GM’s CEO tells Fortune during an interview in a mid-century modern office at the GM Global Technical Center in Warren, Mich. “They want to work for a company that shares their values. When we made our announcement that we were going to make the whole light-duty fleet electric by 2035, we actually saw applications go up.”

Those applicants are signing up for a bumpy ride. Despite their eye- popping investments and production goals, the legacy automakers’ electric future is not guaranteed. For now, Detroit’s accelerated EV pace is fueled more by government mandates than by consumer demand: EVs represented just 4% of the 15 million new vehicles sold in the U.S. in 2021, though the share is quickly growing. And supply-chain challenges, including shortages of semiconductors and raw materials for batteries, rising inflation, and disruptions stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and COVID-related factory shutdowns in China, are making the logistics and finances of EVs even thornier.

Amid that uncertainty, the only certainty is that the city that put America on wheels needs to buckle in for the most momentous transition in its history.

****

BOTH FORD AND GM have experimented with EVs for years, but it’s hard to overstate how much they’ve recently accelerated that commitment. Barra announced in January 2021 that GM would phase out ICE vehicles by 2035. Ford hasn’t committed to a full phaseout, but it now aims to get 50% of sales from EVs by 2030. This March, Ford formalized its transformation with a restructuring that separated its EV business, now called Ford Model e, from its ICE business, Ford Blue. Wall Street embraced Ford’s decision, positing that strong cash flows from Blue could support Ford’s EV expansion.

That dynamic, of internal- combustion profits paying for a zero-emissions future, has already helped both companies overhaul their physical assets. It shows most dramatically in factory footprints across Metro Detroit, where they’re closing old plants, opening new ones, and retooling gas-engine factories to build EVs instead. These real estate decisions have far-reaching repercussions, from the tax base for municipal water to the vitality of the 24-hour Coney Island diners where second- and third-shifters gather after work.

One of the highest-profile conversions is Factory Zero, GM’s new name for its nearly 40-year-old plant in Hamtramck. GM spent $2.2 billion to retool it for EVs, including the battery-electric Chevrolet Silverado and GMC Hummer pickup trucks; President Biden flew into town for its grand opening in November, and Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan gave his State of the City address there in

March. Ford, meanwhile, has invested $700 million outfitting the Rouge complex to build the Lightning; $185 million building Ford Ion Park, a battery laboratory near Detroit Metro Airport; and $250 million on smaller local plants to increase production capacity for the Lightning.

Barra argues that all this production infrastructure gives Detroit a distinct advantage over other cities in the electrification race. Even as software becomes a core part of the vehicle, “we’re still very proud of the fact that we make things,” she says. “As others come into this industry, they’re recognizing the manufacturing piece is hard.”

“We actually have a position of strength that we took for granted for many years,” agrees Glenn Stevens, executive director of MICHauto, the association for Michigan’s automotive companies. “There is no denser cluster in the world of automotive and mobility engineering and manufacturing than in Michigan.” Converting the cluster, Detroit’s honchos argue, is easier than starting from scratch.

GM and Ford are also building more new businesses around EV plat- forms. At GM, for example, the in- house Innovation Lab has incubated BrightDrop, a commercial-delivery EV maker that has contracts to produce vans for FedEx and Walmart; BrightDrop is now hiring hundreds of engineers, software developers, and product designers in Palo Alto, Detroit, and Atlanta. GM also expects the self-driving car company Cruise, of which it is majority shareholder, to produce its first commercial model, the Cruise Origin shuttle, next year at Factory Zero: GM believes Cruise sales to ride-hailing and rental-car companies could become a $50-billion-a-year business by 2030.

In our conversation, Barra gets particularly animated about Ultifi—the cloud-based subscription software service GM is developing. Slated to arrive next year, Ultifi will essentially be the operating system for GM vehicles, capable of regularly upgrading itself like your smart- phone does (and Teslas do): The company says it could generate as much as $25 billion a year in revenue by 2030. Ultifi owners could essentially download automotive features that are currently on the drawing board—like using cameras for facial recognition to start the vehicle, or communicating with drivers’ smart- home applications—without having to buy a new car. Ultifi will interact with third-party apps too; and in an era when software controls more functions on every vehicle, it’ll be an efficient way to repair any bugs.

“The whole concept is that your vehicle can get better as you own it,” says Barra. “Two or three years from now, I can get a feature that didn’t even exist when I bought the vehicle, which is a whole way to reimagine the business.”

****

REIMAGINING THE BUSINESS, of course, means reimagining the workforce: The lingering question is who will fill the retooled factories and at what kind of wages. The skills to build, say, a Ford Mustang are not the same ones needed to create an iPhone on wheels.

All three legacy automakers are quick to dispel the idea that metro Detroit’s traditional assembly line jobs could fade away, to be supplanted by a smaller, savvier workforce. “That’s the fi t important expectation—that we should not be afraid of change,” Stellantis’s Amsterdam-based CEO, Carlos Tavares, tells Fortune. “There will be some change in the general assembly of the vehicles, but nothing that would be scary.”

GM points to Factory Zero to refute fears of layoffs. “The notion that we’re shrinking, that electrification means less jobs, is not the way that we see it,” says Jim Quick, the plant’s executive director. “We’ve announced that we’re going to have about 2,200 jobs–plus. We haven’t had 2,200-plus jobs here in quite some time.” Most of those jobs are unionized: The United Auto Workers union has leaned on the Detroit Three to make sure its members don’t get left behind in the transition.

That said, for workers with “analog” backgrounds, building EV powertrains and batteries requires new training. At GM’s Orion Assembly plant, the entire 1,000-plus person workforce pivoted in 2020 from making gas-engine cars to building the Chevrolet Bolt EV, retraining along the way. (GM says the plant’s workforce will more than triple when it starts making EV pickup trucks.) Many Factory Zero staff underwent reskilling, too. Barra sees retraining as having benefits beyond job preservation: It’s a chance to retool the culture so that opportunities are based on workers’ skills rather than academic credentials. “I think that’s going to open up [advancement] to a whole other realm of people, who don’t think everything has to be done by a four-year degree,” she says.

A wide range of other public and private stakeholders are also developing new educational programs around EV skills. The State of Michigan is awarding grants for groups to develop curriculums for certifications for EV occupations, including dealership technicians and electricians

for charging stations. Even Silicon Valley’s behemoths are getting in on the act. Last summer, Apple opened a Detroit developer academy; it just finished providing its first 100-person cohort, ages 18 to 60, with 10 months of free training in coding and app development. And Google plans to hold free coding classes in the city to help prepare high school students for high-tech jobs, starting next year.

Duggan, Detroit’s three-term mayor, has done his share of lobbying to keep EV jobs local. Talking with a reporter in his 11th-floor City Hall office, Duggan recalls making his case to the Big Three: “I told them, ‘I want you not just to build your electric vehicles here, but I want the entrepreneurs who are designing the electric and automated vehicles of the future to want to locate here.’ ” When Fiat Chrysler was mulling where to build its new Jeep Grand Cherokee plug-in hybrid models, the city offered to handle hiring through job fairs and prescreenings for Detroit residents. In exchange, the automaker made a $1.6 billion commitment to convert its Mack Avenue Engine Complex into a factory that can build EV powertrains; it reopened in June 2021.

“If you put your plant in Detroit, you’re going to have huge help with the workforce,” Duggan says. “If you want to build someplace 40 miles out of Chicago in a cornfield, your hiring is going to be more challenging.”

Still, not every current worker will have a job waiting for them in the electric era. “The EV revolution is going to cost a lot of jobs,” says Grimes, the labor economist. “But so does almost all technological progress.

Think of how many secretarial jobs have been eliminated by computers.” That said, he adds, “it has been a challenge for people to change careers and to move to new towns, but it has ultimately been worth it.” The long-term challenge in Detroit: making sure that retraining and reskilling give people the skills to keep working, even if it means changing professions.

****

RUNNING IN PARALLEL with the retraining is the automakers’ campaign to attract white-collar tech types—which doesn’t necessarily mean attracting them to Detroit. When GM began a few years ago to replace retirees with fresh software talent, the recruitment pitch was not unduly difficult, Barra says. But not all of them are coming to Michigan. The automaker is also staffing up in San Francisco; in Tel Aviv; and at its technical center in Markham, Ontario, where the nearby University of Waterloo is, as Barra notes, “a huge feeder pool to Silicon Valley.”

GM plans to hire 8,000 technical workers this year alone, but it’s giving business-unit managers discretion about where to hire. “This approach helps us compete with tech companies, especially in areas like software, analytics, and AVs [autonomous vehicles],” a spokesman says. “With the remote economy and the absolute thirst for software engineers, [auto- makers are] going to be flexible, just like Microsoft or Google or Amazon,” says Stevens of MICHauto.

Detroit isn’t terra incognita for coders and engineers: Ford and GM already employ thousands of

developers here, and younger techies are already reshaping the city on the surface. If assembly line workers tend to live in bungalows in Sterling Heights or St. Clair Shores and spend weekends at their cottages in Mid-Michigan or the Upper Peninsula, the software crowd is more likely to own condos downtown and spend nights at dining spots like Shelby, a James Beard Award–semifinalist cocktail bar housed in a former bank vault.

But automakers are also develop- ing the kinds of collaborative spaces that draw adventurous STEM talent. Ford is investing $525 million in workforce development around the U.S. by 2026, and one of its most visible efforts is its Research & Engineering Center in Dearborn, a 2-million-square-foot campus that it is redesigning to educate 20,000 Ford designers, engineers, and product developers—the foot soldiers of the EV revolution—by 2025.

Other spaces reach across corporate boundaries. On one downtown artery, an unassuming parking garage houses the Detroit Smart Parking Lab, a new joint effort among Ford, parts supplier Bosch, the State of Michigan, and Bedrock, the commercial real estate firm owned by Quicken Loans cofounder Dan Gilbert.

Operated by the nonprofit American Center for Mobility, the space serves as a collaborative test bed for automotive technology, from charging stations to cloud-based services. Participating companies range from Enterprise Rent-A-Car to Hevo, a startup focused on wireless charging for EVs. “Many of the projects we see, they’re one piece of a puzzle,” said Reuben Sarkar, president and CEO of the mobility center. “By having this laboratory space, we’re actually forming collaborations that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”

Perhaps the most striking emblem of collaboration is Michigan Central Station. One of the city’s most visible examples of urban blight since the last Amtrak train departed in 1988, the once-grand Beaux Arts building in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood is still surrounded by barbed wire to discourage vandals and squatters.

But Ford has invested $950 million to develop the property as a hub for cooperation on transportation tech. Slated to open next year, the complex will house a big cadre of techies from Ford, as well as “landing pads” for other companies, like Google and self-driving car company Argo AI. The center will be a place where innovators can develop, test, and launch technology around autonomous vehicles, public transit, smart roads, and EV infrastructure. And about half of Ford’s 5,000 employees on the campus will come from its current workforce—creating a pipeline from the innovation frontier back to the parent company.

****

DETROIT HAS BEEN synonymous with the U.S. auto industry for so long that it’s easy to forget that most of its domestic production takes place elsewhere. Each of the Big Three makes the majority of its traditional vehicles outside Michigan state lines, and the same will be true of EVs.

GM spent $2 billion retooling its complex in Spring Hill, Tenn.— already its largest facility in North America—to build a range of EVs, including the Cadillac Lyriq, the first battery-electric model from that brand. And that’s a fraction of the $11.4 billion Ford and South Korea’s SK Innovation are investing in Tennessee and Kentucky: The Blue Oval City complex—which will build electric F-Series pickups and advanced batteries—in Stanton, Tenn., and twin battery factories in Glendale, Ky., will together create 11,000 jobs.

Indeed, the increasing globalization of Ford and GM have prompted some local officials to question whether taxpayer money spent on retraining auto workers and attracting tech talent might be better spent elsewhere, including on infrastructure and public education. (Barra, in her conversation with Fortune, high- lighted the city’s beleaguered school system as an obstacle for families considering moving to Detroit.)

At the same time, Michigan and Detroit are less dependent on the auto industry than they were in the 20th century. The logistics, finance, health care, and IT industries have all created steady job growth in the region. Detroit’s unemployment rate re- mains much higher than the national average, at around 10%, but the local economy is in far better shape than it was in the Great Recession, when GM, Chrysler, and the City of Detroit itself all declared bankruptcy.

In short, Detroit is no longer a comeback story. The stakes for the city in the EV transition have to do with quality rather than quantity: Ford, GM, and local officials don’t necessarily want to make more cars here, but they want the Motor City’s workers to remain at the heart of EV innovation—in design, in connectivity, in autonomous driving.

“After decades of struggling to redefine the city’s identity,” Ford’s Farley says, “we’re starting to find our mojo again.” That mojo is palpable in new EV-centric spaces like Factory Zero and the Parking Lab, where Detroit seems to crackle with new energy. Next year, in downtown Detroit, some of that energy will be made visible. On a stretch of Michigan Avenue, local officials will unveil the country’s first public electrified roadway. Developed by Israeli company Electreon and the Michigan Department of Transportation, the infrastructure embedded beneath the road will recharge EVs wirelessly while they drive, park, or wait in traffic. The roadway won’t be far from the inter- section where Detroit introduced the country’s first three-color, four-way traffic light more than 100 years ago— yet another hopeful juxtaposition of Detroit’s future and its past.

****

THE GREAT ELECTRIC BET

America’s Big Three automakers—Fortune 500 giants Ford and General Motors, and Chrysler, now owned by Amsterdam-based Stellantis—have collectively pledged more than $120 billion over the next few years to convert more of their production lines to electric vehicles. Here’s how their bets stack up.

FORD MOTOR CO.

THE COMMITMENT:

50% of sales to come from EVs by 2030

THE INVESTMENT:

$50 billion in EV plants, software, and training through 2026

THE STRATEGY:

Ford will focus first on electrifying its top- selling models, most notably the F-150 Lightning pickup, whose gas-powered version has been a top seller for four decades.

KEY EARLY EV MODELS:

F-150 Lightning, Mus- tang Mach-E SUV, and

E-Transit commercial van (all on sale now).

GENERAL MOTOR

THE COMMITMENT:

100% of global sales to come from EVs by 2035

THE INVESTMENT:

$35 billion in EV and autonomous-vehicle technology through 2025

THE STRATEGY:

GM plans to launch 30 new EVs globally by 2025, almost all of them new models rather than updates of older ones.

KEY EARLY EV MODELS:

Cadillac Lyriq luxury sedan and GMC Hummer pickup (on sale now); Hummer SUV and Chevrolet Silverado pickup (2023).

STELLANTIS

THE COMMITMENT:

100% of European sales and 50% of North Ameri- can sales to come from EVs by 2030

THE INVESTMENT:

$35.5 billion in electrifica- tion, software, and tech- nology through 2025

THE STRATEGY:

In North America, Stel- lantis has focused to date on plug-in hybrid versions of popular models, but it plans to launch at least 25 new EV nameplates.

KEY EARLY EV MODELS:

Chrysler Pacifica and Jeep Grand Cherokee 4xe (on sale now); Jeep Wagoneer 4xe (later this year).