不论大小节日,这样的一幕都是常态——剩饭剩菜堆积成山,它们要么是没有吃完,要么是一看就让人没有胃口。总之,这些食物的归宿就是被塞进冰箱深处。幸运的话,它们会在生出绿毛以前,被你的一些饿着肚子的亲戚从冰箱里翻出来。

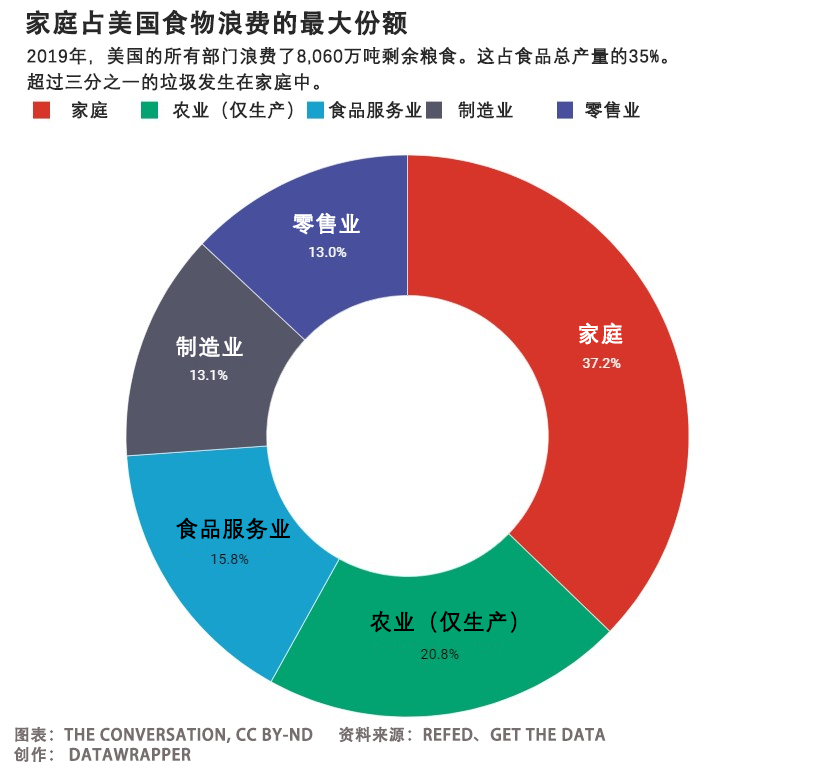

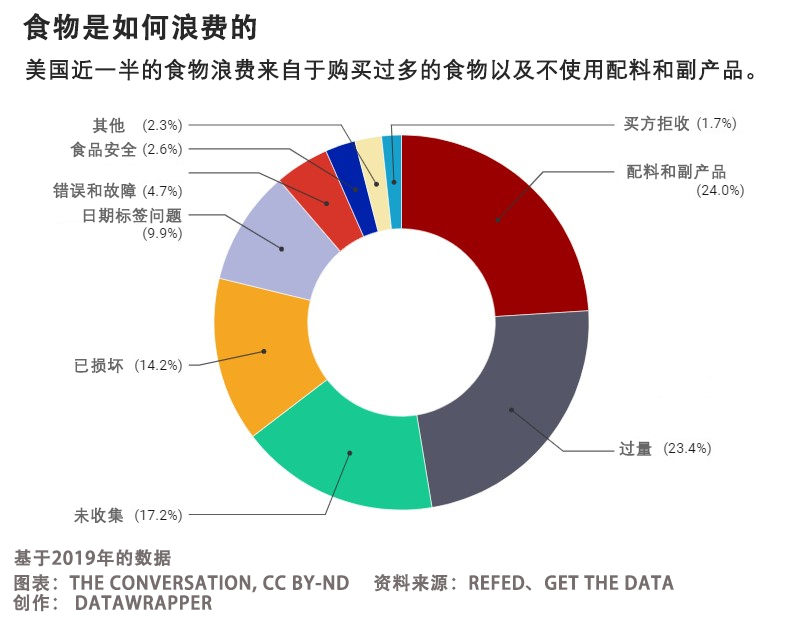

美国人每年浪费的食物极其惊人,所有购买的食物中,大约有三分之一都会被浪费掉,相当于每人每天浪费1,250卡路里的热量,或者一个四口之家每年浪费掉1,500美元的食品。并且这还没有考虑到最近的通胀因素。而且食物一旦变质,相当于用来生产、加工、运输、储存和烹饪这些食物的土地、劳动力、水、化学制品和能源也同样被浪费了。

这些浪费掉的食物都去了哪里?主要是被填埋在了地下。据统计,食品垃圾占全美填埋垃圾的比例达到了四分之一。而食品垃圾被填埋后会分解并产生甲烷气体,这种气体会加重温室效应。美国政府已经认识到了食品浪费的影响,并制定了到2030年前将食品浪费减半的目标。

减少粮食浪费,有助于保护自然资源,为消费者降低开支,减少饥饿人口,延缓气候变化。不过作为一名农业经济学家和俄亥俄州食物浪费合作组织(Ohio State Food Waste Collaborative)的主任,我非常清楚这个问题并没有一个容易的解决方案。要想采取有效的干预措施,就需要深入研究导致食物浪费的系统性原因,理解有哪些外在因素和人为因素造成了这一问题。

消费者与“浪费序列”

为了避免食品浪费,食品在从土壤到端上餐桌的全部过程中,必须避免一系列可能发生的错误。巴鲁克学院(Baruch College)的营销专家劳伦·布洛克和她的同事们将这些错误称为“浪费序列”。

这种事件又被经济学家们称作“O型圈事件”,这个名词得名于1986年的挑战者号航天飞机(Space Shuttle Challenger)失事事件。事故调查表明,一个小小的O型圈零件故障是导致那次事故的罪魁祸首。也就是说,在农产品转化为人体营养的多个步骤里,任何一个微小的因素都会可能导致浪费的发生。

在今天的现代化食品生产消费体系中,最后的环节由谁来负责呢?答案是那些疯狂的、焦头烂额的、时间和金钱都有限的消费者——也就是我们自身。在每个平凡的一天快结束的时候,我们都要千方百计为家人准备一顿营养丰富的、可口的饭菜。

然而现代化的食品生产消费体系是极其复杂的,它并不像管理一家单一的企业那样简单,因为企业只专注于追求利润最大化。普通消费者也并非克雷默设想的那种绝对理性人,能够有效管理复杂的食品消费体系的最终阶段。因此食品的生产消费链条往往最终流于失败或浪费,也就不足为奇了。

事实上,在高度碎片化的美国食品生产消费体系里,消费者在处理和准备食品方面接受的专业培训可能是最少的。而且企业并非总是想帮助消费者从购买的食品中获得最大的价值,因为这样可能会降低它们的销量。而且食品一旦长期存储,口感或者安全性就会下降,这样也会影响生产商的声誉。

杜绝浪费的三条路径

那么,有什么方法可以减少食品浪费呢?这里有几种方法。

·提升消费者的技能。

这一点能够从学生开始,比如可以对家庭教育或者消费科学教育进行投资,打造升级版和现代化的家庭经济学课程。学校也能够在现有课程中添加与食品浪费相关的模块。生物课可以教学生霉菌是怎样形成的,而数学课则能够教学生如何扩大或减少食谱。

在学校以外,人们可以通过网络或者游戏化的体验来进行自学——例如通过品牌好乐门(Hellman’s)的一个名叫“冰箱之夜任务”(Fridge Night Mission)的应用程序,它会教用户怎样从冰箱的食材里多安排出一顿饭来,而且这个过程像网游一样富有挑战感。

近期的研究表明,在新冠疫情爆发初期,很多人封闭在家,不得已重拾厨房管理技能,这时食品浪费就减少了。但是随着疫情管控逐步放开,人们逐渐恢复到新冠疫情前的生活,外出就餐越来越多,食品浪费现象也开始反弹了。

·让在家做饭变得更容易。

消费者不妨尝试购买半成品菜,它提供的食品原材料数量不多不少刚刚好。近期的一项研究表明,与传统的在家做饭相比,半成品菜的浪费量下降了38%。

半成品菜会产生更多的包装废料,但这些额外影响会被食品浪费的下降所抵消。至于它对环境的影响,则要具体问题具体分析,值得开展进一步研究。

·强调食品浪费的后果。

韩国已经开始对家庭食品浪费现象征税了,政府要求老百姓必须用价格昂贵的特殊包装袋处理废弃食品,有的公寓居民则需要通过付费回收箱来丢弃废弃食品。

最近的一项分析显示,只要对每千克的食品浪费征税6美分的税——这大概相当于对一个普通美国家庭每年征收12美元的食品浪费税,这样一来就能够减少近20%的食品浪费。这笔税收还可以促使老百姓每年多花5%的时间用来做饭——也就是每周多花1个小时左右,但却能够让普通家庭每年的食品支出下降约170美元。

没有一劳永逸的解决方案

以上三种方法都很有前景,但这个问题并没有一个单一的解决方案。并不是所有消费者都会主动学习减少食品浪费的技巧。半成品菜会导致一些物流问题,而且对一些家庭来说成本过高。另外,在美国也很少有城市会开发追踪食品浪费以及对食品浪费征税的系统。

美国国家科学、工程和医学院(National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine)在2020年的一份报告中指出,面对全球性的气候变化和营养短缺,必须拿出百花齐放的解决方案来解决食品浪费问题。联合国(United Nations)和美国国家科学基金会(U.S. National Science Foundation)都在资助这方面的研究。我希望这项工作可以帮助我们更清楚地认识食品浪费的模式,并且找到有效的方法来抑制“浪费序列”。(财富中文网)

本文作者布莱恩·E·罗(Brian E. Roe)是美国俄亥俄州立大学(The Ohio State University)农业、环境和发展经济学教授。

译者:朴成奎

不论大小节日,这样的一幕都是常态——剩饭剩菜堆积成山,它们要么是没有吃完,要么是一看就让人没有胃口。总之,这些食物的归宿就是被塞进冰箱深处。幸运的话,它们会在生出绿毛以前,被你的一些饿着肚子的亲戚从冰箱里翻出来。

美国人每年浪费的食物极其惊人,所有购买的食物中,大约有三分之一都会被浪费掉,相当于每人每天浪费1,250卡路里的热量,或者一个四口之家每年浪费掉1,500美元的食品。并且这还没有考虑到最近的通胀因素。而且食物一旦变质,相当于用来生产、加工、运输、储存和烹饪这些食物的土地、劳动力、水、化学制品和能源也同样被浪费了。

这些浪费掉的食物都去了哪里?主要是被填埋在了地下。据统计,食品垃圾占全美填埋垃圾的比例达到了四分之一。而食品垃圾被填埋后会分解并产生甲烷气体,这种气体会加重温室效应。美国政府已经认识到了食品浪费的影响,并制定了到2030年前将食品浪费减半的目标。

减少粮食浪费,有助于保护自然资源,为消费者降低开支,减少饥饿人口,延缓气候变化。不过作为一名农业经济学家和俄亥俄州食物浪费合作组织(Ohio State Food Waste Collaborative)的主任,我非常清楚这个问题并没有一个容易的解决方案。要想采取有效的干预措施,就需要深入研究导致食物浪费的系统性原因,理解有哪些外在因素和人为因素造成了这一问题。

消费者与“浪费序列”

为了避免食品浪费,食品在从土壤到端上餐桌的全部过程中,必须避免一系列可能发生的错误。巴鲁克学院(Baruch College)的营销专家劳伦·布洛克和她的同事们将这些错误称为“浪费序列”。

这种事件又被经济学家们称作“O型圈事件”,这个名词得名于1986年的挑战者号航天飞机(Space Shuttle Challenger)失事事件。事故调查表明,一个小小的O型圈零件故障是导致那次事故的罪魁祸首。也就是说,在农产品转化为人体营养的多个步骤里,任何一个微小的因素都会可能导致浪费的发生。

麻省理工学院(MIT)的经济学家迈克尔·克雷默的研究表明,当很多类型的企业面临这种连续性任务时,它们会把技能最高的员工安排在生产的最后阶段。否则,这些企业就有可能损失掉生产过程中为原材料增加的所有附加值。

在今天的现代化食品生产消费体系中,最后的环节由谁来负责呢?答案是那些疯狂的、焦头烂额的、时间和金钱都有限的消费者——也就是我们自身。在每个平凡的一天快结束的时候,我们都要千方百计为家人准备一顿营养丰富的、可口的饭菜。

然而现代化的食品生产消费体系是极其复杂的,它并不像管理一家单一的企业那样简单,因为企业只专注于追求利润最大化。普通消费者也并非克雷默设想的那种绝对理性人,能够有效管理复杂的食品消费体系的最终阶段。因此食品的生产消费链条往往最终流于失败或浪费,也就不足为奇了。

事实上,在高度碎片化的美国食品生产消费体系里,消费者在处理和准备食品方面接受的专业培训可能是最少的。而且企业并非总是想帮助消费者从购买的食品中获得最大的价值,因为这样可能会降低它们的销量。而且食品一旦长期存储,口感或者安全性就会下降,这样也会影响生产商的声誉。

杜绝浪费的三条路径

那么,有什么方法可以减少食品浪费呢?这里有几种方法。

·提升消费者的技能。

这一点能够从学生开始,比如可以对家庭教育或者消费科学教育进行投资,打造升级版和现代化的家庭经济学课程。学校也能够在现有课程中添加与食品浪费相关的模块。生物课可以教学生霉菌是怎样形成的,而数学课则能够教学生如何扩大或减少食谱。

在学校以外,人们可以通过网络或者游戏化的体验来进行自学——例如通过品牌好乐门(Hellman’s)的一个名叫“冰箱之夜任务”(Fridge Night Mission)的应用程序,它会教用户怎样从冰箱的食材里多安排出一顿饭来,而且这个过程像网游一样富有挑战感。

近期的研究表明,在新冠疫情爆发初期,很多人封闭在家,不得已重拾厨房管理技能,这时食品浪费就减少了。但是随着疫情管控逐步放开,人们逐渐恢复到新冠疫情前的生活,外出就餐越来越多,食品浪费现象也开始反弹了。

·让在家做饭变得更容易。

消费者不妨尝试购买半成品菜,它提供的食品原材料数量不多不少刚刚好。近期的一项研究表明,与传统的在家做饭相比,半成品菜的浪费量下降了38%。

半成品菜会产生更多的包装废料,但这些额外影响会被食品浪费的下降所抵消。至于它对环境的影响,则要具体问题具体分析,值得开展进一步研究。

·强调食品浪费的后果。

韩国已经开始对家庭食品浪费现象征税了,政府要求老百姓必须用价格昂贵的特殊包装袋处理废弃食品,有的公寓居民则需要通过付费回收箱来丢弃废弃食品。

最近的一项分析显示,只要对每千克的食品浪费征税6美分的税——这大概相当于对一个普通美国家庭每年征收12美元的食品浪费税,这样一来就能够减少近20%的食品浪费。这笔税收还可以促使老百姓每年多花5%的时间用来做饭——也就是每周多花1个小时左右,但却能够让普通家庭每年的食品支出下降约170美元。

没有一劳永逸的解决方案

以上三种方法都很有前景,但这个问题并没有一个单一的解决方案。并不是所有消费者都会主动学习减少食品浪费的技巧。半成品菜会导致一些物流问题,而且对一些家庭来说成本过高。另外,在美国也很少有城市会开发追踪食品浪费以及对食品浪费征税的系统。

美国国家科学、工程和医学院(National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine)在2020年的一份报告中指出,面对全球性的气候变化和营养短缺,必须拿出百花齐放的解决方案来解决食品浪费问题。联合国(United Nations)和美国国家科学基金会(U.S. National Science Foundation)都在资助这方面的研究。我希望这项工作可以帮助我们更清楚地认识食品浪费的模式,并且找到有效的方法来抑制“浪费序列”。(财富中文网)

本文作者布莱恩·E·罗(Brian E. Roe)是美国俄亥俄州立大学(The Ohio State University)农业、环境和发展经济学教授。

译者:朴成奎

You saw it at Thanksgiving, and you’ll likely see it at your next holiday feast: piles of unwanted food—unfinished second helpings, underwhelming kitchen experiments, and the like—all dressed up with no place to go, except the back of the refrigerator. With luck, hungry relatives will discover some of it before the inevitable green mold renders it inedible.

S. consumers waste a lot of food year-round, about one-third of all purchased food. That’s equivalent to 1,250 calories per person per day, or $1,500 worth of groceries for a four-person household each year, an estimate that doesn’t include recent food price inflation. And when food goes bad, the land, labor, water, chemicals, and energy that went into producing, processing, transporting, storing, and preparing it are wasted too.

Where does all that unwanted food go? Mainly underground. Food waste occupies almost 25% of landfill space nationwide. Once buried, it breaks down, generating methane, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. Recognizing those impacts, the U.S. government has set a goal of cutting food waste in half by 2030.

Reducing wasted food could protect natural resources, save consumers money, reduce hunger, and slow climate change. But as an agricultural economist and director of the Ohio State Food Waste Collaborative, I know all too well that there’s no ready elegant solution. Developing meaningful interventions requires burrowing into the systems that make reducing food waste such a challenge for consumers, and understanding how both physical and human factors drive this problem.

Consumers and the squander sequence

To avoid being wasted, food must avert a gauntlet of possible missteps as it moves from soil to stomach. Baruch College marketing expert Lauren Block and her colleagues call this pathway the squander sequence.

It’s an example of what economists call an O-ring technology, harking back to the rubber seals whose catastrophic failure caused the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986. As in that event, failure of even a small component in the multistage sequence of transforming raw materials into human nutrition leads to failure of the entire task.

MIT economist Michael Kremer has shown that when corporations of many types are confronted with such sequential tasks, they put their highest-skilled staff at the final stages of production. Otherwise the companies risk losing all the value they have added to their raw materials through the production sequence.

Who performs the final stages of production in today’s modern food system? That would be us: frenzied, multitasking, money- and time-constrained consumers. At the end of a typical day, we’re often juggling myriad demands as we try to produce a nutritious, delicious meal for our households.

Unfortunately, sprawling modern food systems are not managed like a single integrated firm that’s focused on maximizing profits. And consumers are not the highly skilled heavy hitters that Kremer envisioned to manage the final stage of the complex food system. It’s not surprising that failure—here, wasting food—often is the result.

Indeed, out of everyone employed across the fragmented U.S. food system, consumers may have the least professional training in handling and preparing food. Adding to the mayhem, firms may not always want to help consumers get the most out of food purchases. That could reduce their sales—and if food that’s been stored longer degrades and becomes less appetizing or safe, producers’ reputations could suffer.

Three paths to squash the squandering

What options exist for reducing food waste in the kitchen? Here are several approaches.

·Build consumer skills.

This could start with students, perhaps through reinvesting in family and consumer science courses: the modern, expanded realm of old-school home economics classes. Or schools could insert food-related modules into existing classes. Biology students could learn why mold forms, and math students could calculate how to expand or reduce recipes.

Outside of school, there are expanding self-education opportunities available online or via clever gamified experiences like Hellman’s Fridge Night Mission, an app that challenges and coaches users to get one more meal a week out of their fridges, freezers, and pantries. Yes, it may involve adding some mayo.

Recent studies have found that when people had the opportunity to brush up on their kitchen management skills early in the COVID-19 pandemic, food waste declined. However, as consumers returned to busy pre-COVID schedules and routines such as eating out, wastage rebounded.

·Make home meal preparation easier.

Enter the meal kit, which provides the exact quantity of ingredients needed. One recent study showed that compared to traditional home-cooked meals, wasted food declined by 38% for meals prepared from kits.

Meal kits generate increased packaging waste, but this additional impact may be offset by reduced food waste. Net environmental benefits may be case specific, and warrant more study.

·Heighten the consequences for wasting food.

South Korea has begun implementing taxes on food wasted in homes by requiring people to dispose of it in special costly bags or, for apartment dwellers, through pay-as-you-go kiosks.

A recent analysis suggests that a small tax of 6 cents per kilogram—which, translated for a typical U.S. household, would total about $12 yearly—yielded a nearly 20% reduction in waste among the affected households. The tax also spurred households to spend 5% more time, or about an hour more per week, preparing meals, but the changes that people made reduced their yearly grocery bills by about $170.

No silver bullets

Each of these paths is promising, but there is no single solution to this problem. Not all consumers will seek out or encounter opportunities to improve their food-handling skills. Meal kits introduce logistical issues of their own and could be too expensive for some households. And few U.S. cities may be willing or able to develop systems for tracking and taxing wasted food.

As the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine concluded in a 2020 report, there’s a need for many solutions to address food waste’s large contribution to global climate change and worldwide nutritional shortfalls. Both the United Nations and the U.S. National Science Foundation are funding efforts to track and measure food waste. I expect that this work will help us understand waste patterns more clearly and find effective ways to squelch the squander sequence.

Brian E. Roe is a professor of agricultural, environmental, and development economics at The Ohio State University.