美国一直自认为是山巅闪光之城,是不必遵循旧规则的特例。自20世纪90年代中期现代互联网诞生以来,科技巨头例外论已经使硅谷成为经济界的山巅之城——一个正常规则不适用的地方。

Facebook、亚马逊(Amazon)和谷歌(Google)等巨头已经成为历史上市值最高的公司之一,被许多人视为坚不可摧的赚钱机器。即使美国在2008年经济大衰退(Great Recession)后艰难度过“失业式复苏”期,大型科技行业仍然是安·兰德式般的存在,证明美国的科技行业在所有的资本主义国家中依旧鹤立鸡群。技术一直被诟病为损害美国民主和青少年心理健康,甚至导致经济陷入长期停滞。但该行业辩称,创新使其成为例外,它可以在自己的准自由主义黄金国度里运作——监管负担不应该适用,该行业的天才应该不受任何障碍地自由工作。他们指出,FAANGs(美国市场上最受欢迎和表现最佳的五大科技股的首字母缩写)的表现优于标准普尔500指数(S&P 500)就是证明。

有一段时间,这似乎很奏效。在十多年近零利率的支持下,资本似乎全部涌向科技行业。随后,新冠疫情爆发早期推动科技股进一步飙升。但这种狂欢在一年前就结束了,马克·扎克伯格的Meta帝国遭遇了美国历史上上市公司中最大的单日跌幅。从那以后,大型科技公司在所有糟糕的方面都变得异常突出:其他辉煌一时的FAANG公司市值跌幅创下新高;科技巨头解雇了成千上万的员工,而其他经济领域却实现了增长。与此同时,作为终极风险和创新资产的加密货币已经损失了大约三分之二的价值,因为加密货币的“市值”在一年内从3万亿美元缩水到约1万亿美元。

今年3月,当风险投资行业的“思想领袖”沦为最老套的金融恐慌的受害者,那么认为创业经济中的创新领导者卓尔不群的观点就站不住脚了。硅谷银行(Silicon Valley Bank)的倒闭被归咎于美联储(Federal Reserve)监管松懈、美国前总统唐纳德·特朗普时代无能的国会削弱了规则、银行高管管理不善,甚至更令人不可思议的是,还归咎于“(对种族主义、不公等社会问题的)觉醒”或者远程工作太多。诺贝尔奖得主道格拉斯·戴蒙德最近对《财富》杂志的记者肖恩·塔利表示,硅谷银行不是一家普通的银行,该银行相对不稳定的储户群导致其异常脆弱。但事实是:在这个闪光的山谷里,惊慌失措的居民试图在一天内提取420亿美元。正如今年3月流传的一个笑话(套用了扎克伯格的话):科技行业行动太过迅速,以至于为其提供服务的银行都破产了。

显然,早在硅谷银行破产之前,金融体制就已经发生了变化——从宽松货币时代的“万物皆泡沫”,到前所未有的全球货币政策收紧。也许现在,在这种冷静的重新评估中,是时候质疑对风险的认知(在科技例外论时代,风险不断蔓延),并将其从美国创新的主流中拎出来。

创新要走向何方?

科技例外论的理念是基于作者塞巴斯蒂安·马拉比的“幂次定律”(the power law)的,即投资者和发明家可能在前100次冒险中惨败,但只要坚持下去,就有可能在第101次冒险时取得成功——或者正如Meta的首席执行官马克·扎克伯格在2016年所说的那样,要愿意“选择希望而不是恐惧”。

这种理念助长了许多对无利可图的科技股、误入歧途的初创公司和发展方向不明朗的加密货币的高风险押注,因为低息借款时代意味着投资者能够安心地押注于那些越来越荒谬的公司,从Theranos到Juicero再到WeWork。这个非理性时代的碎片包括成千上万的“僵尸”公司和加密货币公司,这些公司在经济上已经维持不下去了,但却以某种方式通过大规模举债来维持生存。这个时代给我们留下了其他各种需要计算的成本,包括肖珊娜·祖博夫所说的“监控型资本主义”,因为智能手机和社交媒体占用了人们越来越多的时间。

斯坦福大学商学院(Stanford Graduate School of Business)的管理学讲师、风险投资家罗伯特·E·西格尔告诉《财富》杂志:“不惜一切代价的创新从来不是一项长期战略。这是在资本廉价、市场存在泡沫的时候采取的一种策略……硅谷银行的破产为低利率超级周期画上了句点,在这个周期中,资本追逐回报,大量资金涌入风险投资和初创公司等高风险高回报资产。”

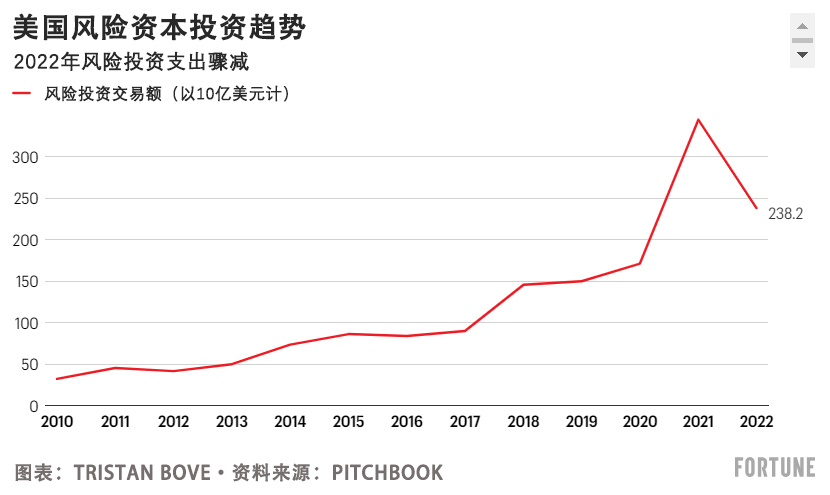

这张支票于2022年到期,当时美联储为了对抗通货膨胀而大举加息,这就像一把锤子砸向了科技行业。包括Meta、亚马逊和苹果(Apple)在内的大公司去年的市值都损失了数千亿美元,而风险投资支出下降了31%。

“冒进的风险投资项目会越来越少”

尽管过去几年科技行业进行着自残式的挥霍,但创新在美国不一定会消亡。但是,如果科技行业想要生存下去,那么就必须改变目前的创新运作方式。这可能意味着彻底抛弃科技例外论的想法。

Meta公司的马克·扎克伯格将2023年定为“效率年”,而亚马逊、谷歌和其他科技公司正在疯狂地削减不再关键的部门和项目——包括员工曾经争先恐后地参与的、几乎不考虑投资回报的“堂吉诃德式登月计划”。

为应对可能到来的经济衰退,那么转而注重提高效率是有意义的。斯坦福大学的西格尔说,美国的创新部门要想保持活力,可能也需要进行精简。他对《财富》杂志表示:“你将会看到这一点:冒进的风险投资项目会越来越少,因为流通的资金将越来越少。糟得一塌糊涂的想法获得投资的几率会越来越小,过剩资金出现的几率也会越来越小。”

科技公司可能也不必独自思考如何更有效地实现创新,因为它拉来了美国政府来解决这个烂摊子。美国国会或者美联储是否可以承担起进行全面改革,从而实现有效监管的重任,仍然有待观察。

“我持谨慎乐观态度。”总部位于纽约的风险投资公司Brooklyn Bridge Ventures的合伙人查理·奥唐奈告诉《财富》杂志。在奥唐奈投资的大约70家公司里,约有三分之一的公司受到硅谷银行破产的影响。他说,他欢迎对风投界进行有效监管:“归根结底,你只想知道规则是什么。你只想要稳定。”

这一切都意味着,科技行业不可能很快回到自由散漫的状态,但该行业能够从2022年的创伤中吸取教训。尽管面临诸多挑战,但美国的创新远未消亡。现在是时候适应这一变化了。(财富中文网)

译者:中慧言-王芳

美国一直自认为是山巅闪光之城,是不必遵循旧规则的特例。自20世纪90年代中期现代互联网诞生以来,科技巨头例外论已经使硅谷成为经济界的山巅之城——一个正常规则不适用的地方。

Facebook、亚马逊(Amazon)和谷歌(Google)等巨头已经成为历史上市值最高的公司之一,被许多人视为坚不可摧的赚钱机器。即使美国在2008年经济大衰退(Great Recession)后艰难度过“失业式复苏”期,大型科技行业仍然是安·兰德式般的存在,证明美国的科技行业在所有的资本主义国家中依旧鹤立鸡群。技术一直被诟病为损害美国民主和青少年心理健康,甚至导致经济陷入长期停滞。但该行业辩称,创新使其成为例外,它可以在自己的准自由主义黄金国度里运作——监管负担不应该适用,该行业的天才应该不受任何障碍地自由工作。他们指出,FAANGs(美国市场上最受欢迎和表现最佳的五大科技股的首字母缩写)的表现优于标准普尔500指数(S&P 500)就是证明。

有一段时间,这似乎很奏效。在十多年近零利率的支持下,资本似乎全部涌向科技行业。随后,新冠疫情爆发早期推动科技股进一步飙升。但这种狂欢在一年前就结束了,马克·扎克伯格的Meta帝国遭遇了美国历史上上市公司中最大的单日跌幅。从那以后,大型科技公司在所有糟糕的方面都变得异常突出:其他辉煌一时的FAANG公司市值跌幅创下新高;科技巨头解雇了成千上万的员工,而其他经济领域却实现了增长。与此同时,作为终极风险和创新资产的加密货币已经损失了大约三分之二的价值,因为加密货币的“市值”在一年内从3万亿美元缩水到约1万亿美元。

今年3月,当风险投资行业的“思想领袖”沦为最老套的金融恐慌的受害者,那么认为创业经济中的创新领导者卓尔不群的观点就站不住脚了。硅谷银行(Silicon Valley Bank)的倒闭被归咎于美联储(Federal Reserve)监管松懈、美国前总统唐纳德·特朗普时代无能的国会削弱了规则、银行高管管理不善,甚至更令人不可思议的是,还归咎于“(对种族主义、不公等社会问题的)觉醒”或者远程工作太多。诺贝尔奖得主道格拉斯·戴蒙德最近对《财富》杂志的记者肖恩·塔利表示,硅谷银行不是一家普通的银行,该银行相对不稳定的储户群导致其异常脆弱。但事实是:在这个闪光的山谷里,惊慌失措的居民试图在一天内提取420亿美元。正如今年3月流传的一个笑话(套用了扎克伯格的话):科技行业行动太过迅速,以至于为其提供服务的银行都破产了。

显然,早在硅谷银行破产之前,金融体制就已经发生了变化——从宽松货币时代的“万物皆泡沫”,到前所未有的全球货币政策收紧。也许现在,在这种冷静的重新评估中,是时候质疑对风险的认知(在科技例外论时代,风险不断蔓延),并将其从美国创新的主流中拎出来。

创新要走向何方?

科技例外论的理念是基于作者塞巴斯蒂安·马拉比的“幂次定律”(the power law)的,即投资者和发明家可能在前100次冒险中惨败,但只要坚持下去,就有可能在第101次冒险时取得成功——或者正如Meta的首席执行官马克·扎克伯格在2016年所说的那样,要愿意“选择希望而不是恐惧”。

这种理念助长了许多对无利可图的科技股、误入歧途的初创公司和发展方向不明朗的加密货币的高风险押注,因为低息借款时代意味着投资者能够安心地押注于那些越来越荒谬的公司,从Theranos到Juicero再到WeWork。这个非理性时代的碎片包括成千上万的“僵尸”公司和加密货币公司,这些公司在经济上已经维持不下去了,但却以某种方式通过大规模举债来维持生存。这个时代给我们留下了其他各种需要计算的成本,包括肖珊娜·祖博夫所说的“监控型资本主义”,因为智能手机和社交媒体占用了人们越来越多的时间。

斯坦福大学商学院(Stanford Graduate School of Business)的管理学讲师、风险投资家罗伯特·E·西格尔告诉《财富》杂志:“不惜一切代价的创新从来不是一项长期战略。这是在资本廉价、市场存在泡沫的时候采取的一种策略……硅谷银行的破产为低利率超级周期画上了句点,在这个周期中,资本追逐回报,大量资金涌入风险投资和初创公司等高风险高回报资产。”

这张支票于2022年到期,当时美联储为了对抗通货膨胀而大举加息,这就像一把锤子砸向了科技行业。包括Meta、亚马逊和苹果(Apple)在内的大公司去年的市值都损失了数千亿美元,而风险投资支出下降了31%。

“冒进的风险投资项目会越来越少”

尽管过去几年科技行业进行着自残式的挥霍,但创新在美国不一定会消亡。但是,如果科技行业想要生存下去,那么就必须改变目前的创新运作方式。这可能意味着彻底抛弃科技例外论的想法。

Meta公司的马克·扎克伯格将2023年定为“效率年”,而亚马逊、谷歌和其他科技公司正在疯狂地削减不再关键的部门和项目——包括员工曾经争先恐后地参与的、几乎不考虑投资回报的“堂吉诃德式登月计划”。

为应对可能到来的经济衰退,那么转而注重提高效率是有意义的。斯坦福大学的西格尔说,美国的创新部门要想保持活力,可能也需要进行精简。他对《财富》杂志表示:“你将会看到这一点:冒进的风险投资项目会越来越少,因为流通的资金将越来越少。糟得一塌糊涂的想法获得投资的几率会越来越小,过剩资金出现的几率也会越来越小。”

科技公司可能也不必独自思考如何更有效地实现创新,因为它拉来了美国政府来解决这个烂摊子。美国国会或者美联储是否可以承担起进行全面改革,从而实现有效监管的重任,仍然有待观察。

“我持谨慎乐观态度。”总部位于纽约的风险投资公司Brooklyn Bridge Ventures的合伙人查理·奥唐奈告诉《财富》杂志。在奥唐奈投资的大约70家公司里,约有三分之一的公司受到硅谷银行破产的影响。他说,他欢迎对风投界进行有效监管:“归根结底,你只想知道规则是什么。你只想要稳定。”

这一切都意味着,科技行业不可能很快回到自由散漫的状态,但该行业能够从2022年的创伤中吸取教训。尽管面临诸多挑战,但美国的创新远未消亡。现在是时候适应这一变化了。(财富中文网)

译者:中慧言-王芳

America has always seen itself as a shining city upon a hill, an exceptional country that doesn’t have to follow the old rules. And since the birth of the modern internet in the mid-1990s, tech exceptionalism has made Silicon Valley the economy’s city on a hill — a place where the normal rules didn’t apply.

Giants such as Facebook, Amazon, and Google have become some of the wealthiest corporations in history, seen by many as indestructible money-making machines. Even as the nation struggled through a “jobless recovery” after the Great Recession of 2008, Big Tech was the Ayn Randian sector proving America had the best of all capitalisms. Technology has been criticized for harming American democracy, youth mental health, and even contributing to long-term economic stagnation. But the sector argued that its innovation made it exceptional enough to operate in its own quasi-libertarian golden state — that regulatory burdens shouldn’t apply, and that its geniuses should be free to work without hurdles. They pointed to the FAANGs outperforming the S&P 500 as proof.

For a time, things seemed to work. Buoyed by over a decade of near-zero interest rates, capital was seemingly everywhere in tech. Then the early pandemic sent tech stocks soaring even higher. But that party ended a year ago, when Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta empire suffered the largest single-day drop of any publicly traded company in American history. Big tech firms have since become exceptional in all the bad ways: the rest of the once-mighty FAANG companies seeing record drops in market cap; and tech giants laying off thousands upon thousands of workers, even as the rest of the economy grows. Meanwhile the ultimate risk and innovation asset, cryptocurrencies, have lost roughly two-thirds of their value, as crypto’s “market cap” shrank from $3 trillion to roughly $1 trillion in a year marked by several huge meltdowns.

The notion, too, that the big brains of the innovators in our startup economy are truly exceptional took a beating in March, when the “thought leaders” that populate the venture capital industry fell victim to the most old-fashioned kind of financial panic. The blow-up of Silicon Valley Bank has been blamed on lax regulation by the Federal Reserve, rules weakened by a feckless Trump-era Congress, mismanagement by bank executives, and even, bizarrely, on “wokeness” or too much remote working. SVB was not a normal bank, and its relatively unstable depositor base rendered it uniquely vulnerable, as Nobel laureate Douglas Diamond recently told Fortune’s Shawn Tully. But the fact remains: The panicked denizens of that shiny valley tried to withdraw $42 billion in one day. As a joke paraphrasing Zuckerberg that was going around March put it: The tech industry moved so fast it broke its own bank.

It was clear long before the collapse of SVB that there has been a financial regime change — from the “everything bubble” of the easy money era to an unprecedented global tightening of monetary policy. Perhaps now, amid this sober reappraisal, is the moment to question the magical thinking about risk that was rampant in the era of tech exceptionalism, and to extract it from the mainstream of American innovation.

W(h)ither innovation?

The idea of tech exceptionalism is grounded in what the author Sebastian Mallaby called “the power law,” the belief that investors and inventors could lose on 100 ventures as long as they succeed on the 101st — or as Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg put it in 2016, the willingness to “choose hope over fear.”

That philosophy fueled many risky bets on unprofitable tech stocks, misguided startups, and directionless cryptocurrencies, as the era of cheap money meant investors were comfortable gambling on increasingly absurd ventures, from Theranos to the Juicero to WeWork. The detritus of this irrational era includes thousands of “zombie” companies and cryptocurrencies, companies that are no longer economically viable but have somehow managed to stay alive by taking on more and more debt. And this era left us with various other costs to calculate, including that of what Shosanna Zuboff has called “surveillance capitalism,” as smartphones and social media invade ever more of people’s time.

“Innovation at all costs is never a long-term strategy,” Robert E. Siegel, a lecturer in management at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and a venture capitalist himself, told Fortune. “That’s a strategy in a moment in time when capital is cheap and there’s frothiness in the market… SVB’s implosion is a punctuation mark at the end of a supercycle of low interest rates where capital was chasing returns, and where there was so much money flowed into high-risk high-return assets like venture and startups.”

The check came due last year with steep interest rate hikes to fight inflation which came down on tech like a hammer. Major companies including Meta, Amazon, and Apple all lost hundreds of billions in market cap last year, while venture capital spending dropped 31%.

“Fewer stupid ventures”

Despite tech’s self-harming lavishness of the past few years, innovation isn’t necessarily dead in the U.S. But the type of innovation practiced by the tech industry will have to operate very differently if it wants to survive. That will likely mean putting to bed once and for all the idea of tech exceptionalism.

Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg has called 2023 the “year of efficiency,” while Amazon, Google, and other tech companies are furiously chopping unnecessary departments and projects — including the Quixotic moonshot projects employees once clamored to work on, with little thought of return on investment.

This pivot to efficiency makes sense in preparation for a possible recession. It might also be the pruning that America’s innovation sector needs to stay alive, said Stanford University’s Siegel. “We’re going to see fewer stupid ventures,” he told Fortune. "You’re going to see this because there's going to be less money to go around. Fewer bad ideas will get funded and there will be less excess.”

Tech probably won’t have to figure out how to innovate more efficiently alone either, as it has invited DC to come in and sort out the mess. It remains to be seen whether Congress or the Federal Reserve are up to the task of overhauling regulation.

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” Charlie O’Donnell, a partner at the New York-based venture capital firm Brooklyn Bridge Ventures, told Fortune. Around a third of the approximately 70 companies in O’Donnell’s portfolio were exposed to SVB’s collapse, and he said he welcomes some thoughtful oversight of the VC world: “At the end of the day, you just want to know what the rules are,” he said. “You just want stability.”

This all means that tech cannot return to its freewheeling ways anytime soon, but the sector can learn from the past year’s trauma. Despite the challenges ahead, innovation in the U.S. is far from dead. It’s time to adapt.