《财富》杂志历史悠久。严格来说,这家“93岁的初创公司”属于沉默一代,不仅在互联网之前,也比邮政编码和碰撞测试假人更早,更不用说报道过的大多数《财富》美国500强公司。事实上,《财富》杂志报道重大商业事件和资本主义文化的时间太久,连自身一些贡献都已经遗忘。“群体思维”现象以及20世纪中期奇怪的投资工具“对冲基金”就是两例。两者并非《财富》杂志发明,但都由《财富》杂志命名。

不过说回来,单词或短语是如何创造出来的?

几十年来,在角落办公室,在工厂车间,在商业领袖聚会之处,《财富》杂志的编辑们轻抖手腕,不断努力开创在全球大环境下具有持久意义的表述。《财富》杂志成立于大萧条(Great Depression)之后,历经了16任总裁、5次当代市场崩溃,还有一场全球疫情,算起来比奥马哈先知沃伦·巴菲特只年长几个月,其实连巴菲特的外号可能也来源于《财富》杂志,出自前任高级主编艾伦·斯隆的笔下。不管怎样,斯隆非常确信在1985年6月为一位杰出竞争对手写文章时首次提到该绰号。

1929年《财富》杂志的发刊词中,创始人亨利·R·卢斯为《财富》杂志风格的定义是:“准确、生动、具体地描述现代商业是新闻史上最伟大的任务。”以下是过去90多年中由《财富》杂志的编辑打造的一些最具代表性的热门词语:

1952年:群体思维

你可能还记得《传播学概论101》(Intro to Communication Theory 101)课程里出现的一个词,因为期末考试中会考,所以经常要加星号、高亮再加下划线,这个词就是“群体思维”(Groupthink)。

1952年3月的一期中,编辑小威廉·H·怀特首次提到该词,灵感来自乔治·奥威尔刚出版不久的杰作《一九八四》(Nineteen Eighty-Four)中“双重思维”(doublethink)一词。小说于1948年上架,背景是反乌托邦的未来伦敦,书中强烈警告人们要反对极权主义。

作为有影响力的社会学家,怀特的职业生涯还很长,后来还吸引了很多颇具社会意识的作家在《财富》杂志发声,其中就包括伟大的城市学家简·雅各布斯的早期作品。他给群体思维的描述是“人类常年失败行为”,意思是人们经常仿效朋友、家人、同事和熟人,却不愿意听取不同意见。

怀特用“群体思维”是为了描述20世纪50年代的美国文化以及管理研究和实践,当今职场却仍然存在。看看美国史上第二大银行倒闭案,即硅谷银行(Silicon Valley Bank)破产案就知道,其背后是老式银行经营模式,只是改换成难以想象的快速版,由社交媒体推动,实际上是由超高速群体思维推动。第一波出问题的传言四散后,监管机构仅用36个小时就关闭了硅谷银行。

怀特解释称,群体思维的危险不仅在于普通人会受到群体中“社会工程师”影响,而且自己也会变成傀儡,“将群体思维当成逃生之路”。

“接受群体思维的人被教导说,人要听别人意见才能够成功,全世界最重要的事情就是成为团队的一员。”怀特写道。在你工作的地方,谁是群体思维的受害者,你自己是不是?

1953年:组织人

你的同事还会把职场中的一面当成自己的个性吗?这已经不符合当前美国职场的新趋势。

1953年5月的《财富》杂志中,当然又有怀特的贡献,该期杂志研究了新兴的管理阶层,他们背井离乡在大城市打拼,然后在适合自己生活方式的郊区定居。此类员工对雇主表现出强烈的奉献精神和忠诚,为“未来的管理方式提供了清晰的画面,”他写道。

“尽管开凯迪拉克(Cadillac)的可能是汽车经销商,还有本地瓶装厂老板,但到最后还是组织人(Organization Man)做出的决策对其他人影响最大。”怀特解释称。

简单来说:他们的生活很大程度受工作的公司影响,个人感觉有强烈的道德义务融入企业文化。

怀特警告说,这一群体正成为美国社会中日益占主导地位的力量,预言将出现缺乏独立、冒险和进步精神的无灵魂文化。

“未来并非由民间传说崇敬的独立企业家或‘粗犷的个人主义者’决定;未来将由组织人决定。”怀特写道。这一概念大受欢迎,后来怀特在同名畅销书中进一步探讨。在引入科学管理概念的“泰勒主义”之后的管理文化文献中,怀特的著作是关键转折点,衔接了1941年詹姆斯·伯纳姆的《管理革命》(The Managerial Revolution)以及1977年约翰·埃伦里奇和芭芭拉·埃伦里奇推出的《职业管理阶层》(the professional-managerial class)。

直到今天,怀特的假设依然成立,因为美国仍然由大公司主导,领导权集中在精英手里。新冠疫情和大辞职潮(Great Resignation)开创了全新的混合办公文化,强调员工的幸福感和选择,员工可以重新安排日常时间,分配育儿职责,改造工作环境,但高盛集团(Goldman Sachs)、迪士尼(Disney)和亚马逊(Amazon)等大公司已经要求员工重返办公室,证明了在个人选择和服从组织之间的紧张关系是多么普遍。

1955年:《财富》美国500强

图片来源:FORTUNE

编辑埃德加·P·史密斯将其称为“灵感乍现”,并在当时表示:“我觉得我们的读者可能会对这个榜单感兴趣。”

自那之后,《财富》美国500强榜单记录了美国顶级企业的起起落落。然而,该榜单的标志性特征在于,在商业领袖和出版商眼中,排名本身已经成为了规模和成功的代名词。

《财富》工业500强(后精简为《财富》美国500强)登上了1955年7月刊封面,并首次与世人见面。传奇人物卡罗尔·卢米斯称,在该榜单发布时,美国经济“有着异常庞大的规模,而且是全世界仰慕的对象。”当时,供职于《财富》杂志的卢米斯刚踏足记者行列。

这些年来,共有2,200多家企业登上了《财富》美国500强榜单。今年的上榜企业共计创造了16.1万亿美元的营收和1.8万亿美元的利润。

1966年:对冲基金

卡罗尔·卢米斯在其漫长而又辉煌的职业生涯中获得了众多奖项,甚至曾经担任过沃伦·巴菲特致伯克希尔-哈撒韦(Berkshire Hathaway)股东年度信函的义务编辑。然而,她对语言的最大贡献莫过于创造了“hedge fund”(对冲基金)一词。1966年4月,卢米斯做了一个有关百万富翁投资者阿尔弗雷德·温斯洛·琼斯(随后也成为了《财富》杂志的撰稿人)的人物专访。尽管阿尔弗雷德被誉为对冲基金教父,但卢米斯才是那个行业的命名者。

对冲基金会集中投资者的资金,然后对股票进行卖空操作,它会使用杠杆来实现其回报的最大化。然而,他们也承担着巨额亏损的风险。在详述琼斯的殷实生活和成功职业的同时,卢米斯认为这种基金是其成功的基石。它使用了杠杆化的资本,而且具有避险特征:“即便投资者误判了大盘趋势,它也会给投资者提供一定的保护。”

卢米斯称,这些投资载体的主要优势在于,对冲基金投资者的短线操作能够让他们做出“最激进的”决策。

在20世纪70年代遭遇滑铁卢之后,随着经理们开发新的投资策略,对冲基金东山再起,在80年代日渐活跃,并于90年代走向兴盛。对冲基金研究公司(Hedge Fund Research)称,趁着牛市高涨的东风,该行业的规模从1990年的389亿美元增至2001年的5,369亿美元。

如今,对冲基金经理正在应对加息以及俄乌冲突所带来的宏观经济和地缘政治挑战。然而,该行业总的来说已经与琼斯那个年代是不可同日而语。对冲基金研究公司称,琼斯的公司在成立时资产规模为10万美元,而2022年第四季度达到了3.83万亿美元的规模。这一年,对冲基金的利润也创下了其有史以来的新高:肯·格里芬的Citadel公司斩获了160亿美元的利润。有谁可以想到,对冲基金曾几何时只不过是阿尔弗雷德·琼斯以及卡罗尔·卢米斯的一个突发奇想罢了。

1989年:花瓶妻子

如今,“花瓶妻子”(trophy wife)不再是一个光鲜靓丽的称谓,通常具有贬义色彩,往往让人联想到那些嫁给了有钱成功人士的女性,但除了自身的外表,这些女性鲜有或毫无其他个人优点。

在20世纪80年代末,人们对美国企业高管精英的离婚变得越发宽容,《财富》杂志的高级编辑朱莉·康奈利不仅杜撰了这个词语,而且预言了这类人的崛起。

康奈利在《财富》杂志1989年8月刊中写道:“人们在经历了喧闹的80年代之后才认为离婚是一件完全合乎情理的事情。”毕竟,在这个10年伊始,罗纳德·里根当选为美国总统,而且是首位处于离异状态的总统。在他入主白宫之后,他与第二任妻子南希·里根结婚。

“如果美国的首席执行官们可以转变这一观念,那么《财富》美国500强企业的首席执行官有何不可?”康奈利说。

妻子“比丈夫年轻10岁或20岁”,她们有的身高比丈夫还高一点,这些女性十分漂亮,而且成就卓著。康奈利对这一越发普遍的现象进行了调查。

康奈利说,这种伴侣“与其丈夫的地位十分相配”,然而,她还肯定地指出:“这种战利品并非像驼鹿头那样,会被挂在墙上。这些女性也会工作,而且很努力。”

2002年:花瓶丈夫

俗话说:“每一位成功人士的背后都有一位伟大的女性。”然而,这句箴言需要更新了。

在杜撰了“花瓶妻子”一词之后,朱莉·康奈利随后发现,越来越多的女性领导者走上了公司高管职位,并与家中的“花瓶丈夫”(trophy husband)共同分担照看孩子的责任。

康奈利写道:“他们有很多称谓,例如家庭主夫、居家奶爸、家务工程师。然而,正是因为他们通过退出、提前退休或做兼职而放弃了自己的职业,自己妻子的职业才能够蒸蒸日上,他的家庭才可以欣欣向荣。”

职业女性的进步十分缓慢但也十分显著:今年,女性首席执行官在《财富》美国500强公司的比例首次超过了10%。

共同育儿责任依然在不断进化。近期对2,000多名美国成人的调查显示,如今,大多数美国民众并不认为女职工就得在家陪孩子。该调查由《财富》杂志委托哈里斯民意调查(The Harris Poll)开展。

反而,超过一半(55%)的受调对象认为,赚钱更少的父母一方应该待在家中照顾孩子。

此外,美国人口普查局(U.S. Census Bureau)称,居家父亲的数量在近些年略有上升。不过,居家父亲的这个定义并未完全涵盖那些未婚或性少数群体中的父亲。

皮尤研究中心(Pew Research Center)的调查显示,2021年美国约有210万居家父亲,较1989年——也就是康奈利杜撰“花瓶妻子”一词的那一年,记录的110万增加了近一倍。

2003年:亨利一族(高收入月光族)

喜欢喝4美元一杯的星巴克咖啡么?

这是“高收入月光族”(High Earner, Not Rich Yet)的典型消费选择,他们一般生活在高消费城市,不在乎每月花了多少钱,一领到薪水就会开始“买买买”。如果你的收入达到六位数,却没有足够的储蓄或投资让自己得以跻身“富人”阶层,那你很可能就属于亨利一族(HENRYs),也是所谓的“高收入月光族”。

肖恩·塔利在1978/79财年加入《财富》杂志,任研究员一职,目前仍然是《财富》杂志的作者,2003年,他提出了“亨利一族”的说法,并在2008年11月一篇介绍年收入超过25万美元却被征收“富人税”人群的文章里重新探讨了这个话题。

出于加税目的,当时还是美国总统候选人的贝拉克·奥巴马和其他国会民主党人常将这些高收入者称为“富人”和“最富有的美国人”,但正如塔利解释的那样,这种说法值得商榷。

塔利解释说:“大多数‘亨利一族’不需要像上百万美国普通百姓那样担心还不上下个月的按揭或信用卡,但把他们和真正的富豪相提并论未免有些言过其实。”

接受塔利采访的亨利一族大多属于双职工家庭,他们表示,联邦税、州税和财产税的增加是造成他们“手头紧”的主要原因,“然后(替代性最低税)又砍了他们一刀”。在孩子身上的投资,比如私立大学的学费、日托班和私人课程(例如舞蹈、网球或体操)的费用也给他们增加了许多压力。

如今,“亨利一族”依然大有人在,和2000年代初一样,除了利率上升造成的压力,他们也在承受着全球经济调整拉低房价带来的痛苦。如今的“亨利一族”大多是千禧一代,他们背负着史上最高的学生贷款,在这代人中年龄最大的一批达到40岁前,他们已经经历了两次历史级的经济衰退。但面临重重压力,谁又能够拒绝一杯星巴克的咖啡呢?

2007年:PayPal黑手党

在开始打造直指火星的重型火箭、设计脑机接口、自称“推特老板”前,美国首富埃隆·马斯克还曾经是“PayPal黑手党”(PayPal Mafia)的一员。

在《财富》杂志的2007年11月刊上,《财富》记者杰弗里·奥布莱恩用“PayPal黑手党”一词报道了带领该公司快速崛起、缔造传奇的管理层,不仅让世界知道了马斯克,也让彼得·蒂尔等未来科技名人走进了大众视野。虽然奥布莱恩在报道中使用了这一名号,但他却不是该词的发明人,真正拥有“版权”的是该公司一众大名鼎鼎的创始人和开发者,包括YouTube的联合创始人陈士骏、查德·赫尔利和贾维德·卡里姆。和战后的美国有组织犯罪团伙一样,经过合并,几家彼此竞争的支付初创企业都赚得盆满钵满。在当时还处于起步阶段的PayPal,风险资本家彼得·蒂尔才是“老板”。

曾经的PayPal是马克斯·列夫钦和蒂尔的“智慧结晶”,志在“改变互联网进程”,如今,该公司已经成功跻身《财富》美国500强。

2002年,PayPal作价15亿美元卖给eBay,此后,该公司大多数关键员工离开了公司,但彼此仍然保持联络。

如今,在许多独角兽企业、初创企业、《财富》美国500强公司都可以看到这些PayPal老员工的身影,比如YouTube、Affirm、特斯拉(Tesla)、推特(Twitter)、领英(LinkedIn)、Yelp、Palantir Technologies、SpaceX和Yammer。

“PayPal的许多老员工都有一个特点,那就是他们都是擅长数学的高智商工作狂人。”奥布莱恩写道:“没有兄弟会成员、工商管理硕士或者什么运动员。”

不过受负面经济环境影响,PayPal的快速增长最近画上了休止符,裁员、股价下跌随之而来,首席执行官也黯然离职。

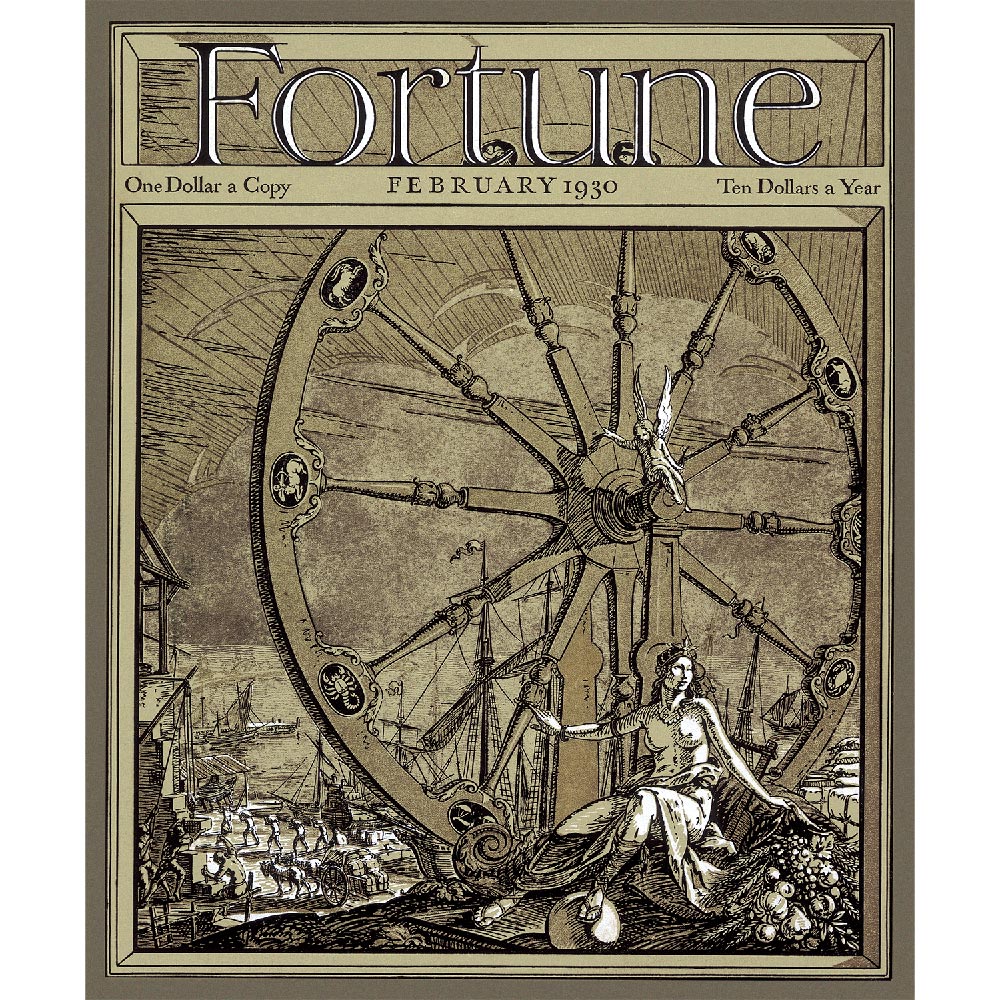

彩蛋:《财富》杂志创刊封面

首期《财富》杂志于1930年2月送到订户手中,封面上印有女神福尔图娜(Fortuna,罗马神话中的幸运女神)和她的车轮。

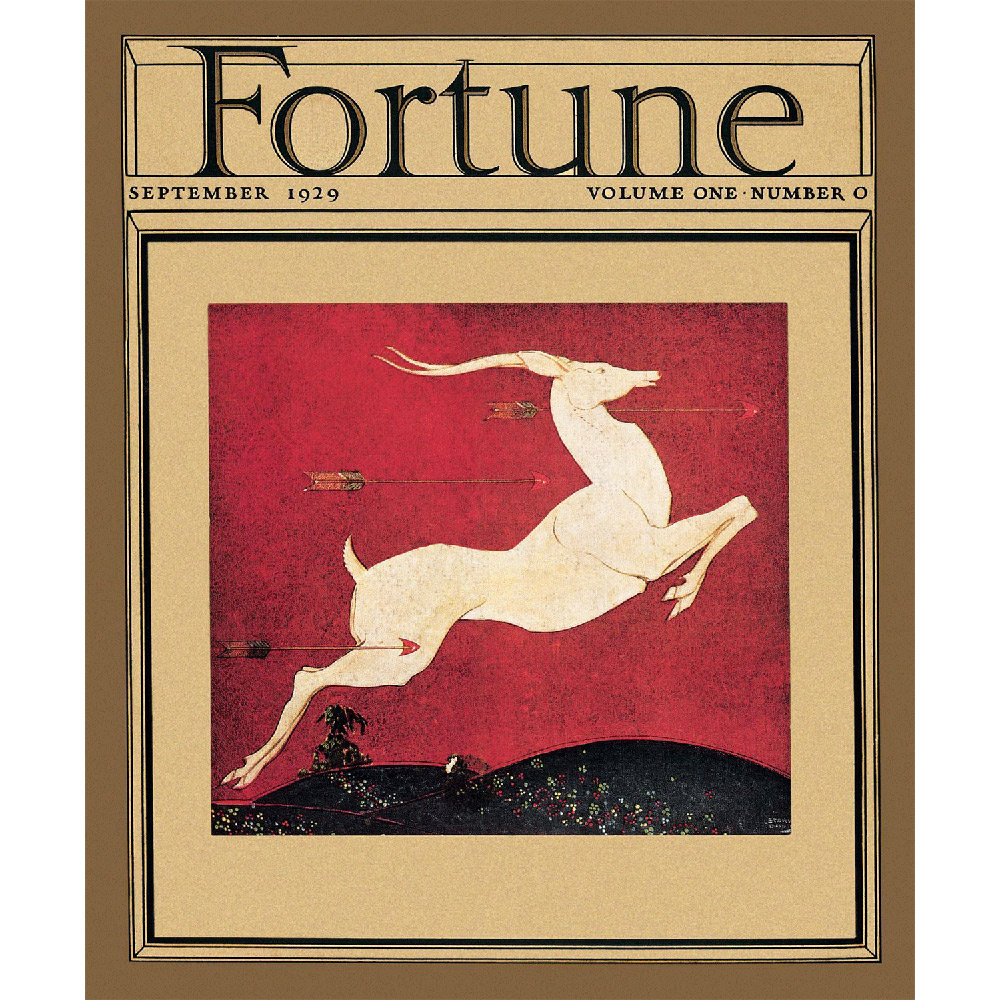

但这并非我们的创刊封面。

在1929年9月给广告商的一封信中,《时代》周刊(Time)的联合创始人亨利·卢斯提出了创办新杂志(提示:《财富》)的想法,并将其收入原型刊《第一卷第0期》之中。

后面的故事大家都知道了。(财富中文网)

译者:梁宇

审校:夏林

《财富》杂志历史悠久。严格来说,这家“93岁的初创公司”属于沉默一代,不仅在互联网之前,也比邮政编码和碰撞测试假人更早,更不用说报道过的大多数《财富》美国500强公司。事实上,《财富》杂志报道重大商业事件和资本主义文化的时间太久,连自身一些贡献都已经遗忘。“群体思维”现象以及20世纪中期奇怪的投资工具“对冲基金”就是两例。两者并非《财富》杂志发明,但都由《财富》杂志命名。

不过说回来,单词或短语是如何创造出来的?

几十年来,在角落办公室,在工厂车间,在商业领袖聚会之处,《财富》杂志的编辑们轻抖手腕,不断努力开创在全球大环境下具有持久意义的表述。《财富》杂志成立于大萧条(Great Depression)之后,历经了16任总裁、5次当代市场崩溃,还有一场全球疫情,算起来比奥马哈先知沃伦·巴菲特只年长几个月,其实连巴菲特的外号可能也来源于《财富》杂志,出自前任高级主编艾伦·斯隆的笔下。不管怎样,斯隆非常确信在1985年6月为一位杰出竞争对手写文章时首次提到该绰号。

1929年《财富》杂志的发刊词中,创始人亨利·R·卢斯为《财富》杂志风格的定义是:“准确、生动、具体地描述现代商业是新闻史上最伟大的任务。”以下是过去90多年中由《财富》杂志的编辑打造的一些最具代表性的热门词语:

1952年:群体思维

你可能还记得《传播学概论101》(Intro to Communication Theory 101)课程里出现的一个词,因为期末考试中会考,所以经常要加星号、高亮再加下划线,这个词就是“群体思维”(Groupthink)。

1952年3月的一期中,编辑小威廉·H·怀特首次提到该词,灵感来自乔治·奥威尔刚出版不久的杰作《一九八四》(Nineteen Eighty-Four)中“双重思维”(doublethink)一词。小说于1948年上架,背景是反乌托邦的未来伦敦,书中强烈警告人们要反对极权主义。

作为有影响力的社会学家,怀特的职业生涯还很长,后来还吸引了很多颇具社会意识的作家在《财富》杂志发声,其中就包括伟大的城市学家简·雅各布斯的早期作品。他给群体思维的描述是“人类常年失败行为”,意思是人们经常仿效朋友、家人、同事和熟人,却不愿意听取不同意见。

怀特用“群体思维”是为了描述20世纪50年代的美国文化以及管理研究和实践,当今职场却仍然存在。看看美国史上第二大银行倒闭案,即硅谷银行(Silicon Valley Bank)破产案就知道,其背后是老式银行经营模式,只是改换成难以想象的快速版,由社交媒体推动,实际上是由超高速群体思维推动。第一波出问题的传言四散后,监管机构仅用36个小时就关闭了硅谷银行。

怀特解释称,群体思维的危险不仅在于普通人会受到群体中“社会工程师”影响,而且自己也会变成傀儡,“将群体思维当成逃生之路”。

“接受群体思维的人被教导说,人要听别人意见才能够成功,全世界最重要的事情就是成为团队的一员。”怀特写道。在你工作的地方,谁是群体思维的受害者,你自己是不是?

1953年:组织人

你的同事还会把职场中的一面当成自己的个性吗?这已经不符合当前美国职场的新趋势。

1953年5月的《财富》杂志中,当然又有怀特的贡献,该期杂志研究了新兴的管理阶层,他们背井离乡在大城市打拼,然后在适合自己生活方式的郊区定居。此类员工对雇主表现出强烈的奉献精神和忠诚,为“未来的管理方式提供了清晰的画面,”他写道。

“尽管开凯迪拉克(Cadillac)的可能是汽车经销商,还有本地瓶装厂老板,但到最后还是组织人(Organization Man)做出的决策对其他人影响最大。”怀特解释称。

简单来说:他们的生活很大程度受工作的公司影响,个人感觉有强烈的道德义务融入企业文化。

怀特警告说,这一群体正成为美国社会中日益占主导地位的力量,预言将出现缺乏独立、冒险和进步精神的无灵魂文化。

“未来并非由民间传说崇敬的独立企业家或‘粗犷的个人主义者’决定;未来将由组织人决定。”怀特写道。这一概念大受欢迎,后来怀特在同名畅销书中进一步探讨。在引入科学管理概念的“泰勒主义”之后的管理文化文献中,怀特的著作是关键转折点,衔接了1941年詹姆斯·伯纳姆的《管理革命》(The Managerial Revolution)以及1977年约翰·埃伦里奇和芭芭拉·埃伦里奇推出的《职业管理阶层》(the professional-managerial class)。

直到今天,怀特的假设依然成立,因为美国仍然由大公司主导,领导权集中在精英手里。新冠疫情和大辞职潮(Great Resignation)开创了全新的混合办公文化,强调员工的幸福感和选择,员工可以重新安排日常时间,分配育儿职责,改造工作环境,但高盛集团(Goldman Sachs)、迪士尼(Disney)和亚马逊(Amazon)等大公司已经要求员工重返办公室,证明了在个人选择和服从组织之间的紧张关系是多么普遍。

1955年:《财富》美国500强

编辑埃德加·P·史密斯将其称为“灵感乍现”,并在当时表示:“我觉得我们的读者可能会对这个榜单感兴趣。”

自那之后,《财富》美国500强榜单记录了美国顶级企业的起起落落。然而,该榜单的标志性特征在于,在商业领袖和出版商眼中,排名本身已经成为了规模和成功的代名词。

《财富》工业500强(后精简为《财富》美国500强)登上了1955年7月刊封面,并首次与世人见面。传奇人物卡罗尔·卢米斯称,在该榜单发布时,美国经济“有着异常庞大的规模,而且是全世界仰慕的对象。”当时,供职于《财富》杂志的卢米斯刚踏足记者行列。

这些年来,共有2,200多家企业登上了《财富》美国500强榜单。今年的上榜企业共计创造了16.1万亿美元的营收和1.8万亿美元的利润。

1966年:对冲基金

卡罗尔·卢米斯在其漫长而又辉煌的职业生涯中获得了众多奖项,甚至曾经担任过沃伦·巴菲特致伯克希尔-哈撒韦(Berkshire Hathaway)股东年度信函的义务编辑。然而,她对语言的最大贡献莫过于创造了“hedge fund”(对冲基金)一词。1966年4月,卢米斯做了一个有关百万富翁投资者阿尔弗雷德·温斯洛·琼斯(随后也成为了《财富》杂志的撰稿人)的人物专访。尽管阿尔弗雷德被誉为对冲基金教父,但卢米斯才是那个行业的命名者。

对冲基金会集中投资者的资金,然后对股票进行卖空操作,它会使用杠杆来实现其回报的最大化。然而,他们也承担着巨额亏损的风险。在详述琼斯的殷实生活和成功职业的同时,卢米斯认为这种基金是其成功的基石。它使用了杠杆化的资本,而且具有避险特征:“即便投资者误判了大盘趋势,它也会给投资者提供一定的保护。”

卢米斯称,这些投资载体的主要优势在于,对冲基金投资者的短线操作能够让他们做出“最激进的”决策。

在20世纪70年代遭遇滑铁卢之后,随着经理们开发新的投资策略,对冲基金东山再起,在80年代日渐活跃,并于90年代走向兴盛。对冲基金研究公司(Hedge Fund Research)称,趁着牛市高涨的东风,该行业的规模从1990年的389亿美元增至2001年的5,369亿美元。

如今,对冲基金经理正在应对加息以及俄乌冲突所带来的宏观经济和地缘政治挑战。然而,该行业总的来说已经与琼斯那个年代是不可同日而语。对冲基金研究公司称,琼斯的公司在成立时资产规模为10万美元,而2022年第四季度达到了3.83万亿美元的规模。这一年,对冲基金的利润也创下了其有史以来的新高:肯·格里芬的Citadel公司斩获了160亿美元的利润。有谁可以想到,对冲基金曾几何时只不过是阿尔弗雷德·琼斯以及卡罗尔·卢米斯的一个突发奇想罢了。

1989年:花瓶妻子

如今,“花瓶妻子”(trophy wife)不再是一个光鲜靓丽的称谓,通常具有贬义色彩,往往让人联想到那些嫁给了有钱成功人士的女性,但除了自身的外表,这些女性鲜有或毫无其他个人优点。

在20世纪80年代末,人们对美国企业高管精英的离婚变得越发宽容,《财富》杂志的高级编辑朱莉·康奈利不仅杜撰了这个词语,而且预言了这类人的崛起。

康奈利在《财富》杂志1989年8月刊中写道:“人们在经历了喧闹的80年代之后才认为离婚是一件完全合乎情理的事情。”毕竟,在这个10年伊始,罗纳德·里根当选为美国总统,而且是首位处于离异状态的总统。在他入主白宫之后,他与第二任妻子南希·里根结婚。

“如果美国的首席执行官们可以转变这一观念,那么《财富》美国500强企业的首席执行官有何不可?”康奈利说。

妻子“比丈夫年轻10岁或20岁”,她们有的身高比丈夫还高一点,这些女性十分漂亮,而且成就卓著。康奈利对这一越发普遍的现象进行了调查。

康奈利说,这种伴侣“与其丈夫的地位十分相配”,然而,她还肯定地指出:“这种战利品并非像驼鹿头那样,会被挂在墙上。这些女性也会工作,而且很努力。”

2002年:花瓶丈夫

俗话说:“每一位成功人士的背后都有一位伟大的女性。”然而,这句箴言需要更新了。

在杜撰了“花瓶妻子”一词之后,朱莉·康奈利随后发现,越来越多的女性领导者走上了公司高管职位,并与家中的“花瓶丈夫”(trophy husband)共同分担照看孩子的责任。

康奈利写道:“他们有很多称谓,例如家庭主夫、居家奶爸、家务工程师。然而,正是因为他们通过退出、提前退休或做兼职而放弃了自己的职业,自己妻子的职业才能够蒸蒸日上,他的家庭才可以欣欣向荣。”

职业女性的进步十分缓慢但也十分显著:今年,女性首席执行官在《财富》美国500强公司的比例首次超过了10%。

共同育儿责任依然在不断进化。近期对2,000多名美国成人的调查显示,如今,大多数美国民众并不认为女职工就得在家陪孩子。该调查由《财富》杂志委托哈里斯民意调查(The Harris Poll)开展。

反而,超过一半(55%)的受调对象认为,赚钱更少的父母一方应该待在家中照顾孩子。

此外,美国人口普查局(U.S. Census Bureau)称,居家父亲的数量在近些年略有上升。不过,居家父亲的这个定义并未完全涵盖那些未婚或性少数群体中的父亲。

皮尤研究中心(Pew Research Center)的调查显示,2021年美国约有210万居家父亲,较1989年——也就是康奈利杜撰“花瓶妻子”一词的那一年,记录的110万增加了近一倍。

2003年:亨利一族(高收入月光族)

喜欢喝4美元一杯的星巴克咖啡么?

这是“高收入月光族”(High Earner, Not Rich Yet)的典型消费选择,他们一般生活在高消费城市,不在乎每月花了多少钱,一领到薪水就会开始“买买买”。如果你的收入达到六位数,却没有足够的储蓄或投资让自己得以跻身“富人”阶层,那你很可能就属于亨利一族(HENRYs),也是所谓的“高收入月光族”。

肖恩·塔利在1978/79财年加入《财富》杂志,任研究员一职,目前仍然是《财富》杂志的作者,2003年,他提出了“亨利一族”的说法,并在2008年11月一篇介绍年收入超过25万美元却被征收“富人税”人群的文章里重新探讨了这个话题。

出于加税目的,当时还是美国总统候选人的贝拉克·奥巴马和其他国会民主党人常将这些高收入者称为“富人”和“最富有的美国人”,但正如塔利解释的那样,这种说法值得商榷。

塔利解释说:“大多数‘亨利一族’不需要像上百万美国普通百姓那样担心还不上下个月的按揭或信用卡,但把他们和真正的富豪相提并论未免有些言过其实。”

接受塔利采访的亨利一族大多属于双职工家庭,他们表示,联邦税、州税和财产税的增加是造成他们“手头紧”的主要原因,“然后(替代性最低税)又砍了他们一刀”。在孩子身上的投资,比如私立大学的学费、日托班和私人课程(例如舞蹈、网球或体操)的费用也给他们增加了许多压力。

如今,“亨利一族”依然大有人在,和2000年代初一样,除了利率上升造成的压力,他们也在承受着全球经济调整拉低房价带来的痛苦。如今的“亨利一族”大多是千禧一代,他们背负着史上最高的学生贷款,在这代人中年龄最大的一批达到40岁前,他们已经经历了两次历史级的经济衰退。但面临重重压力,谁又能够拒绝一杯星巴克的咖啡呢?

2007年:PayPal黑手党

在开始打造直指火星的重型火箭、设计脑机接口、自称“推特老板”前,美国首富埃隆·马斯克还曾经是“PayPal黑手党”(PayPal Mafia)的一员。

在《财富》杂志的2007年11月刊上,《财富》记者杰弗里·奥布莱恩用“PayPal黑手党”一词报道了带领该公司快速崛起、缔造传奇的管理层,不仅让世界知道了马斯克,也让彼得·蒂尔等未来科技名人走进了大众视野。虽然奥布莱恩在报道中使用了这一名号,但他却不是该词的发明人,真正拥有“版权”的是该公司一众大名鼎鼎的创始人和开发者,包括YouTube的联合创始人陈士骏、查德·赫尔利和贾维德·卡里姆。和战后的美国有组织犯罪团伙一样,经过合并,几家彼此竞争的支付初创企业都赚得盆满钵满。在当时还处于起步阶段的PayPal,风险资本家彼得·蒂尔才是“老板”。

曾经的PayPal是马克斯·列夫钦和蒂尔的“智慧结晶”,志在“改变互联网进程”,如今,该公司已经成功跻身《财富》美国500强。

2002年,PayPal作价15亿美元卖给eBay,此后,该公司大多数关键员工离开了公司,但彼此仍然保持联络。

如今,在许多独角兽企业、初创企业、《财富》美国500强公司都可以看到这些PayPal老员工的身影,比如YouTube、Affirm、特斯拉(Tesla)、推特(Twitter)、领英(LinkedIn)、Yelp、Palantir Technologies、SpaceX和Yammer。

“PayPal的许多老员工都有一个特点,那就是他们都是擅长数学的高智商工作狂人。”奥布莱恩写道:“没有兄弟会成员、工商管理硕士或者什么运动员。”

不过受负面经济环境影响,PayPal的快速增长最近画上了休止符,裁员、股价下跌随之而来,首席执行官也黯然离职。

彩蛋:《财富》杂志创刊封面

首期《财富》杂志于1930年2月送到订户手中,封面上印有女神福尔图娜(Fortuna,罗马神话中的幸运女神)和她的车轮。

但这并非我们的创刊封面。

在1929年9月给广告商的一封信中,《时代》周刊(Time)的联合创始人亨利·卢斯提出了创办新杂志(提示:《财富》)的想法,并将其收入原型刊《第一卷第0期》之中。

后面的故事大家都知道了。(财富中文网)

译者:梁宇

审校:夏林

Yes, Fortune is old. The “93-year-old startup” is technically a member of the Silent Generation, predating the invention of not just the internet but also zip codes and crash test dummies, not to mention most of the Fortune 500 companies we cover. In fact, we’ve been covering monumental business events and the culture of capitalism for so long that we’ve forgotten some of our contributions to it. Take the phenomenon of “groupthink” or the curious midcentury investment vehicle “the hedge fund.” Fortune didn’t invent either of these things, but we were first to name them.

But how does one invent a word or a phrase, anyway?

With the flick of a wrist and copious time spent around copious time spent in corner offices, on factory floors, and anywhere else business leaders congregate, Fortune has been generating timeless phrases in our global vernacular for decades. Founded in the wake of the Great Depression, the magazine has persisted through 16 presidents, five contemporary market crashes, and a global pandemic. That makes us just a few months senior to Warren Buffett, the Oracle of Omaha himself, whose popular nickname may even have originated in Fortune—it was bestowed by former Fortune senior editor-at-large Allan Sloan. However, Sloan is pretty sure that he coined the moniker while writing a June 1985 article for one of our distinguished competitors.

In a 1929 prospectus for the magazine, founder Henry R. Luce defined Fortune’s style, proclaiming that “accurately, vividly and concretely to describe Modern Business is the greatest journalistic assignment in history.” Here is a sampling of some of the most iconic descriptions that Fortune editors have minted over the past nine decades:

Groupthink: 1952

You may recall from your Intro to Communication Theory 101 course one vocabulary term that was to be starred, highlighted, and underlined because it would appear on your final exam: Groupthink.

In our March 1952 issue, editor William H. Whyte Jr. introduced the term, inspired by the phrase “doublethink” in George Orwell’s recently released masterpiece, Nineteen Eighty-Four. Set in a dystopian future version of London, the novel hit bookshelves in 1948 with a strong warning against totalitarianism.

Whyte would go on to a long career as an influential sociologist and would bring the voices of many socially minded writers into Fortune’s pages, including early work by the great urbanist Jane Jacobs. He described groupthink as a “perennial failing of mankind” in which we copy our friends, family, coworkers, and acquaintances, and fail to listen to dissenting opinions.

While Whyte used “groupthink” to describe American culture and the study and practice of management in the 1950s, the phenomenon is still alive and well in our present-day workplace. Look no further than the second-biggest banking collapse in American history, the demise of Silicon Valley Bank, which featured a once unthinkably fast version of an old-school bank run, powered by social media but really by groupthink at hyperspeed. It only took 36 hours for regulators to shutter SVB after the first rumblings of trouble started.

The danger with groupthink, Whyte explains, is not only that the average person will be influenced by the “social engineers” of the group, but that they will become another puppeteer themselves and “embrace groupthink as the road to security.”

The “groupthinker is taught that one wins by being directed by others — and that the most important thing in the world is to be a team player,” Whyte writes. Who in your workplace is a victim of groupthink, or is it even you?

Organization Man: 1953

Do your coworkers make their jobs their entire personality? That’s far from a new trend in corporate America.

For our May 1953 issue, Whyte was at it again, studying the emerging class of managers who had left their hometowns to start careers in big cities before settling in suburban communities that fit their lifestyles. These workers exuded a strong commitment and loyalty to their employers, and provided the “sharpest picture of tomorrow’s management,” he writes.

“Though it may be the automobile dealer and the owner of the local bottling franchise who drive the Cadillacs, it is the organization man who now makes the decisions that most affect the lives of others,” Whyte explains.

Simply put: Their personal life is heavily influenced by the company that they work for, and the individual feels a very strong moral obligation to fit into that corporate culture.

Whyte warned that this cohort was becoming an increasingly dominant force in American society and prophesized a soulless culture lacking in independence, risk-taking, and progress.

“The future will be determined not by the independent entrepreneur or the ‘rugged individualist’ whom our folklore so venerates; the future will be determined by Organization Man,” Whyte writes. The concept was such a hit that Whyte would go on to further explore the topic in the bestselling book of the same name. In the literature on managerial culture in the aftermath of “Taylorism,” which introduced the concept of scientific management, Whyte’s book was a key pivot point spanning James Burnham’s 1941 work, “The Managerial Revolution,” and John and Barbara Ehrenreich’s coining of “the professional-managerial class” in 1977.

Whyte’s hypothesis stands true today, as America continues to be dominated by large companies with leadership concentrated in the hands of the country’s elites. The COVID-19 pandemic and Great Resignation ushered in a new culture of hybrid work with an emphasis on employee happiness and choice, allowing employees to reinvent their daily schedules, parenting duties, and work environments, but return-to-office mandates at the largest companies, including Goldman Sachs, Disney, and Amazon, demonstrate the prevalence of that tension between individual choice and organizational conformity.

Fortune 500: 1955

Editor Edgar P. Smith called it a “lightbulb moment,” saying at the time: “I think that our readers just might be interested in this list.”

The Fortune 500 list has catalogued the rise and fall of America’s biggest companies ever since, but the iconic nature of the list is clear from how the ranking itself has become synonymous among business leaders and publishers as a shorthand for big and successful.

First gracing our cover in the July 1955 edition, the “Fortune Industrial 500”—later shortened to Fortune 500—was first published at a time when the U.S. economy was “colossal in size and the envy of the world,” according to the legendary Carol Loomis, who was then a rookie reporter on the magazine’s staff.

Over the years, more than 2,200 companies have graced the Fortune 500 list. This year’s ranking collectively generated a record $16.1 trillion in revenue and $1.8 trillion in profits.

Hedge fund: 1966

Carol Loomis won many awards throughout her long and illustrious career, and even served as the pro bono editor of Warren Buffett’s annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway’s shareholders, but her biggest contribution to the language may have been when she coined the phrase “hedge fund.” In April 1966, Loomis profiled the millionaire investor Alfred Winslow Jones (who would later become a Fortune contributor himself), and while he is credited for being the father of the hedge fund industry, Loomis became the person who named an entire sector.

By pooling investors’ money and short-selling stocks, hedge funds use leverage to maximize their returns, but they also risk intensified losses. As she chronicled Jones’ affluent lifestyle and successful career, Loomis defined this kind of fund as the engine of his success. Such funds use capital that is both leveraged and “hedged,” which puts the investor in a position that “partially shelters him if he misjudges the general trend of the market.”

The main advantage to these investment vehicles, according to Loomis, is that the hedge fund investor’s short position enables them to make decisions with “maximum aggressiveness.”

After a crash in the 1970s, hedge funds benefited from a resurgence in the go-go ‘80s and subsequent boom in the ‘90s as managers developed new strategies for investing. Riding the high of a bull market, the industry grew from $38.9 billion in 1990 to $536.9 billion in 2001, according to Hedge Fund Research (HFR).

Today, hedge fund managers are navigating macroeconomic and geopolitical challenges from interest rate hikes and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but the industry overall has surged from Jones’ day to ours. Jones’ firm launched with $100,000 in assets while the industry was $3.83 trillion in size as of the fourth quarter of 2022, according to HFR. That year also saw the greatest profit in hedge-fund history: $16 billion from Ken Griffin’s Citadel. And to think, once it was a twinkle in Alfred Jones’ eye and a tickle in Carol Loomis’ brain.

Trophy wife: 1989

It’s not really okay to describe someone as a “trophy wife” anymore. Often a derogatory phrase, it can easily imply that a woman married to a wealthy, successful spouse has little to no personal merit other than her physical appearance.

In the late 1980s, during a time of growing acceptance of divorce among corporate America’s power elite, Fortune senior editor Julie Connelly not only coined the phrase but defined its rise.

As Connelly writes in the August 1989 issue, “it took the roaring Eighties to make divorce fully respectable.” After all, the decade began with the election of America’s first divorced president, Ronald Reagan, who was remarried to his second wife, Nancy Reagan, when he moved into the White House.

“If the CEO of the United States could shed and rewed, why not the CEO of a Fortune 500 company?” Connelly posited.

Connelly surveyed the rising prominence of a spouse “a decade or two younger than her husband, sometimes several inches taller, beautiful, and very often accomplished.”

This partner “certifies her husband’s status,” Connelly said, but she was sure to note: “this trophy does not hang on the wall like a moose head—she works. Hard.”

Trophy husband: 2002

As the old adage states: “behind every great man is a great woman.” But that quote needs some updates.

After coining “trophy wife,” Julie Connelly later documented the increasing number of women leaders climbing the corporate ladder while sharing parenting duties with a “trophy husband” at home.

“Call him what you will: househusband, stay-at-home dad, domestic engineer,” Connelly writes. “But credit him with setting aside his own career by dropping out, retiring early, or going part-time so that his wife’s career might flourish and their family might thrive.”

Progress for working women is slow but measurable: This year, for the first time in history, women CEOs ran more than 10% of companies on the Fortune 500.

Co-parenting duties are still evolving, too. Today, most Americans don’t assume working mothers will stay at home with their kids, according to a recent survey of more than 2,000 U.S. adults conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of Fortune.

Instead, more than half (55%) of respondents believe the parent making less money should be the one who stays home with the kids.

Additionally, the number of stay-at-home dads has increased slightly in recent years, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, though that definition doesn’t fully encapsulate the full scope of fathers including those who are unmarried or identify as LGBTQ+.

According to Pew Research Center, an estimated 2.1 million stay-at-home dads were living in the U.S. in 2021. That’s up from 1.1 million stay-at-home dads recorded in 1989, the same year Connelly coined “trophy wife.”

HENRYs (High Earners, Not Rich Yet): 2003

How about that $4 cup of Starbucks?

It’s a spending choice symbolic of a particular demographic: The person who spends money as soon as it hits the checking account, resides in a city with a high cost of living city, and usually neglects their monthly budget. If you earn six figures but don’t have enough in savings or investments to be considered “rich,” then this might be you. You’re a HENRY, a “High Earner, Not Rich Yet.”

Fortune writer Shawn Tully, who is still on staff today, having first been hired as a researcher in 1978/79, first introduced the world to the “HENRYs” in 2003, and revisited the subject in an article in the November 2008 issue that described individuals earning over $250,000 annually but getting taxed to “high heaven.”

At the time, then-presidential nominee Barack Obama and other congressional Democrats frequently referred to these high earners as the “rich” and the “wealthiest Americans” in a push for more tax increases, but that’s debatable, as Tully explains.

“Unlike millions of Americans, most HENRYs don’t need to worry about making the next mortgage or credit card payment,” Tully explains. “Still, HENRYs are getting a bad rap from those who lump them in with America’s conspicuously wealthy.”

Mostly members of two-income families, HENRYs interviewed by Tully said they were strapped for cash mainly due to rising federal, state, and property taxes, “plus the knife of the [Alternative Minimum Tax].” They blamed the squeeze on investments in their children, including paying for private colleges, day care, and private lessons, like “dance, tennis, or gymnastics.”

HENRYs are still alive and well today, and are also still feeling the pressure from falling home prices from a global correction in addition to rising interest rates, just like the early 2000s. The majority of today’s HENRYs are millennials, who are saddled with unprecedented levels of student debt and have weathered two historic recessions before the oldest of them reached the age of 40. But who can really resist a Starbucks in a time of stress?

PayPal Mafia: 2007

Before America’s richest person built rocket ships destined for Mars, designed implants for the human brain, and nicknamed himself “Chief Twit,” Elon Musk was a member of the “PayPal Mafia.”

Fortune’s Jeffrey O’Brien profiled the leaders behind the online payments company’s monumental rise in the November 2007 issue, introducing the world to not just Musk but other future tech luminaries such as Peter Thiel. While O’Brien reported this coinage, he didn’t create it; the supercharged roster of founders and developers including the likes of YouTube cofounders Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim gave themselves the name “PayPal mafia.” Like American organized crime in the postwar period, the merger of several rival payment startups made them all richer, and the title of “don” at the then-fledgling company was reserved for venture capitalist Peter Thiel.

Now a Fortune 500 company, PayPal was once a “brainchild” of Max Levchin and Thiel that “would change the course of the Internet.”

After selling out to eBay for $1.5 billion in 2002, most of PayPal’s key employees left the company but stayed in touch.

Altogether, these PayPal veterans have gone on to work with unicorns, startups, and Fortune 500 companies including YouTube, Affirm, Tesla, Twitter, LinkedIn, Yelp, Palantir Technologies, SpaceX, and Yammer.

“Many of PayPal’s early hires matched a specific profile: highly intelligent workaholics who were good at math. No frat boys, MBAs, or, God forbid, jocks,” O’Brien writes.

More recently, however, economic headwinds have halted PayPal’s history of breakneck growth, resulting in layoffs, slumping shares, and a CEO exit.

Bonus: Fortune’s First Cover

The very first issue of Fortune that was distributed to subscribers beginning in February 1930 featured the Roman goddess Fortuna with her wheel on its cover.

However, that wasn’t our first-ever cover.

In a letter to advertisers in September 1929, Time co-founder Henry Luce proposed a new magazine (hint: Fortune) and included it in a prototype issue, “Volume One, Number 0.”

The rest is history.