美国尚未迎来黎明。不可否认,无论从哪方面来看,乔·拜登政府领导下的美国经济都是非常强劲的,因此他开始在各大媒体用自创的新词“拜登经济学”作为竞选主题,讲述一个具有富兰克林·罗斯福色彩的里根式的故事,即产业政策和支持工会的组合“由内而外、自下而上”重建经济。但有一个重要的问题:美国大多数有影响力的选民都是中上阶层的专业人士,他们的生活比拜登上任前变得更差,而他们则是民主党的选民基础。

经过中期选举后,美国两大政党似乎越来越专注于2024年的总统大选,而经济在选民心目中扮演了重要角色。拜登总统应该感到担忧,因为本月发布的许多民调显示,面对悲观的消费者和工人,拜登很难为自己的经济政策辩护。

《纽约时报》(New York Times)在上周声称“选民不相信拜登经济学”。其与锡耶纳学院(Siena College)的联合民调显示,在摇摆州的民调中,现任总统拜登很难与共和党可能的竞选对手(和前任总统)唐纳德·特朗普对抗。美国全国广播公司(NBC)在11月9日写道:“美国人对稳健的经济异常失望。”

事实上,大部分的美国人都不满意。在Bankrate于11月8日发布的调查里,有一半受访者表示自2020年以来,其个人财务状况恶化,有近70%的受访者提到原因是生活成本的暴涨。决策情报公司Morning Consult的调查显示,消费者尤其是中等收入家庭的信心,在过去两个月持续下降。

求职网站Glassdoor的首席经济学家阿伦·特拉萨斯对《财富》杂志表示:“人们的感受与数据体现的状况之间似乎严重脱节。”

蓝领工人大获全胜

自疫情以来的经济复苏在许多方面都不同寻常,而受教育程度和收入水平较低的工人的出色表现尤其明显。

自新冠疫情爆发以来,最低收入阶层的工人工资增长速度最快,这逆转了过去三十年每次经济扩张的趋势。亚马逊(Amazon)的一位员工在今年2月匿名写道,这是“蓝领工人的复仇”。当时,雇主招聘了50万蓝领工人,但科技公司裁员10,000人。

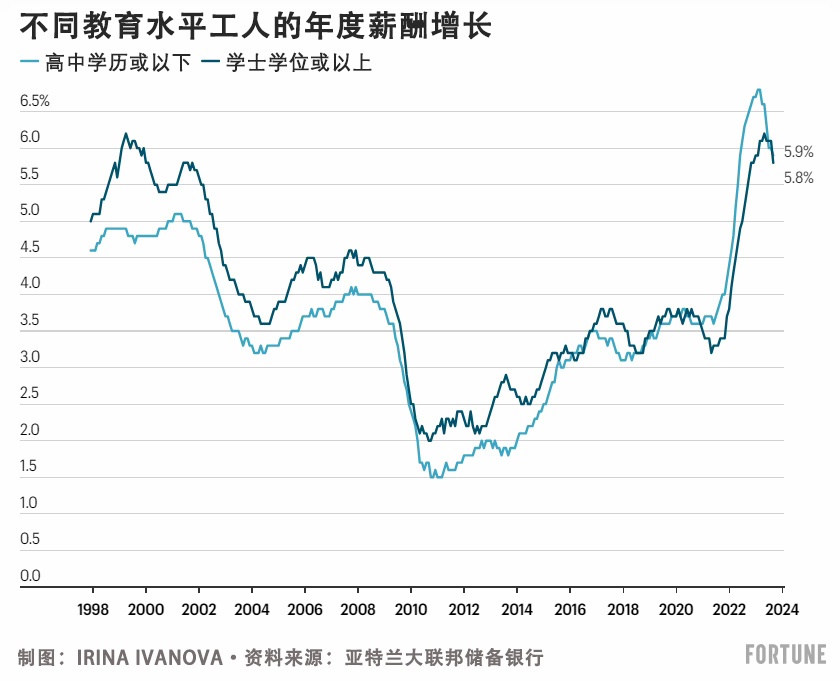

求职网站ZipRecruiter的首席经济学家朱莉娅·波拉克称:“这完全是非典型的趋势。新冠疫情和人手不足以及工人的影响力增加,对低收入工人来说是一个巨大的推动。”同样,高中学历以下的工人的薪酬增长速度,超过了大学毕业的工人,上一次出现这种情况至少是在20世纪90年代末。

这种现象的问题在于,受教育程度较高的白领上班族,现在是民主党的选民基础。(各种族的)大学毕业生更支持民主党,他们对民主党和共和党的支持率相差24个百分点,而没有大学学位的选民更支持共和党,支持率相差12个百分点。自20世纪90年代末,比尔·克林顿时期的“新民主党”开始的大转变,现在达到了最高峰。新民主党强调社会进步主义,并推行新自由主义改革,这对美国工薪阶层造成了持续性的伤害。工薪阶层选民的支持率下降甚至威胁到民主党之前在拉丁裔和亚裔美国人选民中争取到的支持,因为所有种族的工薪阶层选民都支持共和党。

拜登的经济议程试图扭转这个长达数十年的摆脱经济民粹主义的趋势,但效果有限。

不仅顶级白领的收入增长速度低于为他们端咖啡和照顾孩子的工人的收入增长速度,而且许多职场精英还要面对截然不同的就业市场:机会更少、要求更多。据路透社(Reuters)报道,最惨淡的是科技和传媒行业,自去年秋季以来,这些行业的工资下降了3%,而这种趋势在金融业同样明显,银行业者预计他们的奖金与去年相比会大幅减少。

(相比之下,建筑业的工资较去年增长了近3%,医疗和教育行业工资上涨了4%,而石油和天然气开采业的工资上涨了近5%。)

有工作的人对于被要求重返办公室或者找新工作,并不感到激动。特拉萨斯说:“员工灵活性、薪酬和福利方面的快速转变,让习惯了丰厚待遇的白领上班族非常不满。”

通胀的影响

除了就业市场以外,还有另外一个令美国人不满的主要因素,那就是生活成本。虽然年通胀率与去年的超高水平相比已经大幅下降,但官方通胀数据并没有考虑到高利率的影响,这使得购房、买车等大额消费甚至持有信用卡欠款,变得成本极其高昂。

Bankrate驻华盛顿负责人马克·哈姆里克告诉《财富》杂志:“通胀率下降,但物价并未下降。如果你现在打算买一辆普通的新车,比如50,000美元,你就需要每个月还款1,000美元。人们有理由感觉定价环境对他们不利。”

这是坏消息,因为许多研究显示,即使在选民的净资产增长速度超过物价时,他们对通胀上涨的感受,也比对工资上涨的感受更强烈。甚至有研究显示,人们最常购买的食品杂货和汽油等商品,比在他们的预算中占大部分的商品,更容易影响他们的态度。

Morning Consult的高级经济学家杰西·惠勒表示:“人们在食品杂货店支付的价格显而易见,如果你的食品杂货账单比两年前增加了30%或60%,这是非常明显的。”

他补充道:“通胀会影响所有人,而收入增长虽然会影响许多人,但并非所有人的收入都在增长。升职加薪是你努力工作所获得的,是你应得的。而当你去商店时,却需要为同样的商品支付更高的价格。前者感觉是你个人努力付出的回报;后者则感觉是你被迫付出的代价。”(财富中文网)

译者:刘进龙

审校:汪皓

美国尚未迎来黎明。不可否认,无论从哪方面来看,乔·拜登政府领导下的美国经济都是非常强劲的,因此他开始在各大媒体用自创的新词“拜登经济学”作为竞选主题,讲述一个具有富兰克林·罗斯福色彩的里根式的故事,即产业政策和支持工会的组合“由内而外、自下而上”重建经济。但有一个重要的问题:美国大多数有影响力的选民都是中上阶层的专业人士,他们的生活比拜登上任前变得更差,而他们则是民主党的选民基础。

经过中期选举后,美国两大政党似乎越来越专注于2024年的总统大选,而经济在选民心目中扮演了重要角色。拜登总统应该感到担忧,因为本月发布的许多民调显示,面对悲观的消费者和工人,拜登很难为自己的经济政策辩护。

《纽约时报》(New York Times)在上周声称“选民不相信拜登经济学”。其与锡耶纳学院(Siena College)的联合民调显示,在摇摆州的民调中,现任总统拜登很难与共和党可能的竞选对手(和前任总统)唐纳德·特朗普对抗。美国全国广播公司(NBC)在11月9日写道:“美国人对稳健的经济异常失望。”

事实上,大部分的美国人都不满意。在Bankrate于11月8日发布的调查里,有一半受访者表示自2020年以来,其个人财务状况恶化,有近70%的受访者提到原因是生活成本的暴涨。决策情报公司Morning Consult的调查显示,消费者尤其是中等收入家庭的信心,在过去两个月持续下降。

求职网站Glassdoor的首席经济学家阿伦·特拉萨斯对《财富》杂志表示:“人们的感受与数据体现的状况之间似乎严重脱节。”

蓝领工人大获全胜

自疫情以来的经济复苏在许多方面都不同寻常,而受教育程度和收入水平较低的工人的出色表现尤其明显。

自新冠疫情爆发以来,最低收入阶层的工人工资增长速度最快,这逆转了过去三十年每次经济扩张的趋势。亚马逊(Amazon)的一位员工在今年2月匿名写道,这是“蓝领工人的复仇”。当时,雇主招聘了50万蓝领工人,但科技公司裁员10,000人。

求职网站ZipRecruiter的首席经济学家朱莉娅·波拉克称:“这完全是非典型的趋势。新冠疫情和人手不足以及工人的影响力增加,对低收入工人来说是一个巨大的推动。”同样,高中学历以下的工人的薪酬增长速度,超过了大学毕业的工人,上一次出现这种情况至少是在20世纪90年代末。

这种现象的问题在于,受教育程度较高的白领上班族,现在是民主党的选民基础。(各种族的)大学毕业生更支持民主党,他们对民主党和共和党的支持率相差24个百分点,而没有大学学位的选民更支持共和党,支持率相差12个百分点。自20世纪90年代末,比尔·克林顿时期的“新民主党”开始的大转变,现在达到了最高峰。新民主党强调社会进步主义,并推行新自由主义改革,这对美国工薪阶层造成了持续性的伤害。工薪阶层选民的支持率下降甚至威胁到民主党之前在拉丁裔和亚裔美国人选民中争取到的支持,因为所有种族的工薪阶层选民都支持共和党。

拜登的经济议程试图扭转这个长达数十年的摆脱经济民粹主义的趋势,但效果有限。

不仅顶级白领的收入增长速度低于为他们端咖啡和照顾孩子的工人的收入增长速度,而且许多职场精英还要面对截然不同的就业市场:机会更少、要求更多。据路透社(Reuters)报道,最惨淡的是科技和传媒行业,自去年秋季以来,这些行业的工资下降了3%,而这种趋势在金融业同样明显,银行业者预计他们的奖金与去年相比会大幅减少。

(相比之下,建筑业的工资较去年增长了近3%,医疗和教育行业工资上涨了4%,而石油和天然气开采业的工资上涨了近5%。)

有工作的人对于被要求重返办公室或者找新工作,并不感到激动。特拉萨斯说:“员工灵活性、薪酬和福利方面的快速转变,让习惯了丰厚待遇的白领上班族非常不满。”

通胀的影响

除了就业市场以外,还有另外一个令美国人不满的主要因素,那就是生活成本。虽然年通胀率与去年的超高水平相比已经大幅下降,但官方通胀数据并没有考虑到高利率的影响,这使得购房、买车等大额消费甚至持有信用卡欠款,变得成本极其高昂。

Bankrate驻华盛顿负责人马克·哈姆里克告诉《财富》杂志:“通胀率下降,但物价并未下降。如果你现在打算买一辆普通的新车,比如50,000美元,你就需要每个月还款1,000美元。人们有理由感觉定价环境对他们不利。”

这是坏消息,因为许多研究显示,即使在选民的净资产增长速度超过物价时,他们对通胀上涨的感受,也比对工资上涨的感受更强烈。甚至有研究显示,人们最常购买的食品杂货和汽油等商品,比在他们的预算中占大部分的商品,更容易影响他们的态度。

Morning Consult的高级经济学家杰西·惠勒表示:“人们在食品杂货店支付的价格显而易见,如果你的食品杂货账单比两年前增加了30%或60%,这是非常明显的。”

他补充道:“通胀会影响所有人,而收入增长虽然会影响许多人,但并非所有人的收入都在增长。升职加薪是你努力工作所获得的,是你应得的。而当你去商店时,却需要为同样的商品支付更高的价格。前者感觉是你个人努力付出的回报;后者则感觉是你被迫付出的代价。”(财富中文网)

译者:刘进龙

审校:汪皓

It’s not quite morning in America. Joe Biden’s economy is undeniably strong almost every way you look at it, such that he’s begun campaigning on the media portmanteau “Bidenomics,” pitching a Reaganesque story with an FDR twist—that his combination of industrial policy and pro-union support is rebuilding the economy “from the middle out, and the bottom up.” There’s just one big problem, though: Most of America’s influential voters are upper-middle-class professionals who are a bit worse off than before he took office, and they comprise the Democratic base.

With the off-year elections in the rearview mirror, the two major political parties increasingly appear locked in for the 2024 presidential contest, with the economy taking a starring role in voters’ minds. And that’s a worry for the president, as a flurry of polls released this month show Biden struggling to defend his economic policies against pessimistic consumers and workers.

“‘Voters Aren’t Believing in Bidenomics,” the New York Times declared last week, showcasing a joint poll with Siena that showed the president struggling in battleground state polls against his likely GOP opponent (and predecessor), Donald Trump. “Americans are unusually down on a solid economy,” NBC wrote on November 9.

Indeed, most Americans are dour. Half of respondents to a Bankrate survey released on November 8 said that their personal finances had gotten worse since 2020, and nearly seven in 10 cited a surge in living expenses. A survey by Morning Consult, a decision intelligence company, shows consumer sentiment has been dropping for two months, particularly among middle-income households.

“There seems to be this massive disconnect between what people are feeling and what the data are saying,” Aaron Terrazas, chief economist at job site Glassdoor, told Fortune.

Blue-collar workers win big

The economic recovery since the pandemic has been unusual in many ways—but especially in how well less-educated and lower-paid workers have done.

In a reversal of every economic expansion for the last three decades, wages since the pandemic have grown fastest for workers in the lowest-paid rungs. It’s the “revenge of the blue-collar worker,” one anonymous Amazon worker wrote in February, a month that saw employers hire half a million people but tech companies lay off 10,000.

“It’s totally, totally atypical,” said Julia Pollak, chief economist for job site ZipRecruiter. “The pandemic and the labor shortages and increase in worker leverage has been a huge boost for lower-income workers.” In a similar vein, pay growth for workers with less than a high school degree has outpaced growth of college-educated workers—the first time since at least the late 1990s that this has occurred.

That’s a problem because those well-educated white-collar workers now make up the Democratic Party’s base. College graduates (of all races) support Democrats over Republicans by a 24-point margin; those without degrees favor the GOP by 12 points. It’s the culmination of a great shift that began with the Clinton-era “New Democrats” of the late 1990s, which emphasized social progressivism while pushing through neoliberal reforms that did lasting damage to America’s working class. The declining popularity among working-class voters is even threatening Democrats’ earlier gains among Hispanics and Asian-Americans, as working-class voters of all ethnicities break toward the GOP.

It’s that decades-long shift away from economic populism that Biden’s economic agenda is attempting to reverse, albeit in a limited way.

Not only is pay for the top tiers of white-collar workers growing more slowly than for the people who serve them coffee and look after their kids, but many of the office elite are facing an entirely different job market—one with fewer prospects and more requirements. It’s the most dire in the tech and media sector, where payrolls have shrunk 3% since last fall, but also visible in finance, where bankers are expecting their bonuses to shrink substantially from last year, according to Reuters.

(Compare that to employment in construction, which is up nearly 3% from last year, or health care and education, up 4%, or oil and gas extraction, up nearly 5%.)

Those who are still employed are less than thrilled at being told to return to the office—or find another job. “The rapid shift around employee flexibility, compensation, and benefits has generated a lot of resentment among white-collar workers who are used to being treated exceptionally well,” said Terrazas.

It’s the inflation, stupid

Besides the job market, there's another major factor getting Americans annoyed—the cost of living. While the annual rate of inflation has slowed substantially from its scorching-hot levels of last year, the official inflation figure leaves out the impact of high interest rates, which make big-ticket purchases like a home, a car, or even carrying a credit card balance prohibitively expensive.

“Inflation’s coming down, but prices aren’t,” Mark Hamrick, Washington bureau chief at Bankrate, told Fortune. “If you want a typical new car right now, you’re talking $50,000, and you’re looking at a payment of $1,000 a month. People rightly feel like the pricing environment isn’t in their favor.”

That’s bad news because plenty of research has shown that voters feel rising inflation much more than they do raising wages—even when their own net worth is growing faster than prices. Some research even suggests that the purchases people make most often—such as groceries and gasoline—shape their attitudes more than the items that make up the bulk of their budget.

“What people are paying in the grocery story—that’s such a visible price, and when you pay 30% or 60% more on your grocery bill than you did two years ago, that’s really noticeable,” said Jesse Wheeler, senior economist at Morning Consult.

“Inflation impacts everyone, and those income gains, while they affect a lot of people, maybe isn’t everyone,” he added. “A raise or a promotion, it’s something that you worked for, you earned it. And then you go to the store and you have to pay more for the same stuff. One feels like a personal, earned item; the other one feels like it was done to you.”