怎样把用户研究透?这家公司是榜样

|

在Intuit首席执行官布拉德·史密斯办公室墙外,订着董事会成员对他的业绩评价,未经修改。还有一份性格分析,一份高管团队提供的反馈摘要,还有他安排时间的计划。评价里大部分是溢美之词,也有不好听的。“保持正常节奏就好,”他的团队说。“这家伙总是精力过剩。”有时“他的反馈过于温和,我们更希望听到他直截了当地说,‘嘿,这事你搞砸了。’”董事会成员认为他“谈话时最好随意一些,别总是那么一板一眼。”(史密斯承认他特别有条理,每天下班收件箱一定会清空,“衣柜里的衣架间隙都会严格保持两指距离。”)董事会还认为他应该“公开提供更多有建设性的反馈。”对他来说这是另一种挑战。史密斯承认,“内心深处就不愿意那么做。” 所有这些反馈都是公开的。只要花上五分钟读一读史密斯办公室门外各种反馈,你就能深入了解他,可能比某些每天共事的同事还要熟悉。当然了,Intuit里8200名员工不可能人人都去史密斯办公室门口转一圈,所以他每年都把所有反馈打包发给所有人。 |

Taped to the wall outside Intuit CEO Brad Smith’s office is his unedited performance review from the board of directors. Also a personality analysis, a compendium of feedback from his executive team, and a breakdown of how he spends his time. Most of it is laudatory; some isn’t. “A normalized pace would be good,” his team says. “This guy is always on hyperkinetic energy.” Sometimes “his feedback is wrapped in so much niceness—we’d love to hear straight up, ‘Look, you fumbled.’ ” The board thinks he should “be willing to have more unstructured conversations—not everything buttoned up.” (Smith admits he’s so highly structured that his email in-box is empty at the end of every day and “I have two fingers between the hangers in my closet.”) The board also thinks he needs “to be willing to give constructive feedback in public.” That will be another challenge. Smith says, “My heart won’t let me do that.” All of this feedback is publicly displayed. Spend five minutes reading the material next to Smith’s office door and you’ll know more about him than you know about some of the people you work with every day. Of course most of Intuit’s 8,200 employees will never walk past Smith’s office—so he emails the whole package to all of them each year. |

|

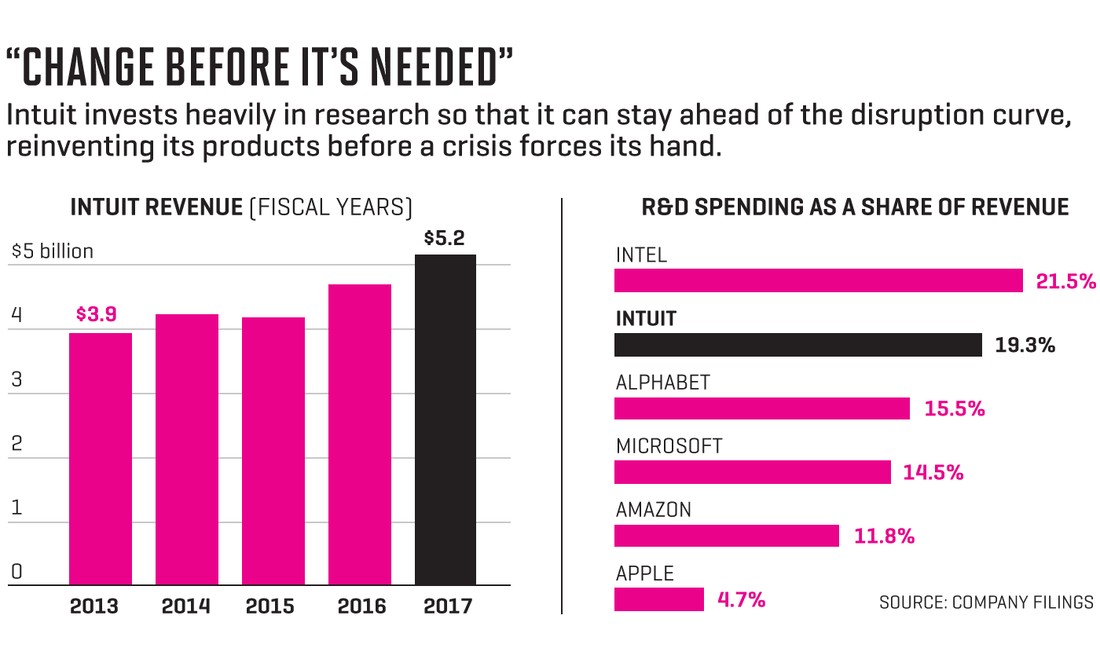

公开透明当然是好的,但做这么绝可能让人觉得荒谬。Intuit内部员工都觉得很正常,这也是解开一项秘密的线索。秘密是:为什么Intuit能长盛不衰?在新排出的《财富》未来50强里Intuit排名第八,明年发展势头更好,收入预计会大幅增长。但这家企业已经34岁了,比很多企业历史都要久。其涉及的业务是专业的个人电脑软件,面临的竞争非常激烈。1983年成立以来,很多曾经的同行(例如Flexidraw、VisiCalc等)早已消失。 然而Intuit不仅蒸蒸日上,而且发展速度极快。据EVA Dimensions咨询公司统计,其收入已达52亿美元,较2012年增长了36%;利润也创下纪录。资本回报率达到60%,资本成本仅为6.9%,所以评定Intuit的财务状况超过99%的上市公司。Intuit比很多著名的创业公司盈利还高,比很多现有同行发展速度又快很多。即便股价创下新高,几乎所有分析师还是建议买入。Intuit简直就是商界的橄榄球明星汤姆·布拉迪,汤姆在很多同龄人退役之后仍然保持着极佳的竞技水平。 部分原因是:从成立开始,Intuit就做到了现在每家企业都在学习的一点,不断颠覆自身,在竞争对手超越之前积极调整产品线和商业模型。 Intuit最初的产品是Quicken个人财务软件,遭到微软的Windows旗下DOS系统排挤后只能重找出路。上世纪90年代的新产品包括为小企业会计处理开发的QuickBooks和为个人纳税开发的TurboTax,都迅速打败了竞争对手,互联网发端后Intuit专门开发出网络版,移动互联网时代再次改版。回想起来仿佛都很简单,但每次转型都意味着思路大调整,在手机上申报税务?但Intuit确实做到了,也成功避免了常见的大企业病。 目前其自我颠覆可能比以往任何一次都要激进,五年前高管层决定Intuit不只当产品和服务提供商,应该成为开放平台。“小公司平均使用16到20款软件,我们只做了其中三款,”53岁的史密斯表示,他担任首席执行官一职已经10年。“所以我们应该开放自己的平台,相信此举可以提升客户忠诚度,也能借此更深入地了解需要解决的问题。” 如今全公司都在赌,赌的是打造在线开放平台欢迎外部开发者——也包括潜在竞争对手之后,实力只会增强而不会削弱。届时开发者可以提供与Intuit产品兼容的应用。举个例子,美国运通向运通商务信用卡持卡人提供免费应用,每日可自动将转账交易记录在QuickBooks在线账户里。这对美国运通来说是个卖点,QuickBooks用户管理账目也更方便,也会更依赖开放平台。 |

Transparency is great, but this, you might think, is ridiculous. No one seems to think so at Intuit (INTU, +0.86%) , however, and that’s a clue to a mystery worth solving. It’s this: Why is Intuit still here? It’s No. 8 on Fortune’s new ranking of the Future 50, the companies best prepared to thrive and grow their revenue rapidly in coming years. Yet at age 34 it’s older than almost all the others. Its business, specialized personal-computing software, is brutally competitive. All its peers from 1983 (Flexidraw, VisiCalc) are long gone. Yet Intuit is not just surviving, it’s blowing the doors off. Revenue, at $5.2 billion, is up 36% since 2012; profits are at an all-time high. Return on capital is a towering 60%, while cost of capital is a measly 6.9%, according to the EVA Dimensions consulting firm, which ranks Intuit’s financial performance in the 99th percentile of all public companies. Intuit is simultaneously more profitable than glamorous startups and growing faster than established incumbents. Even as its stock hits new highs, nearly all analysts rate it a buy. This is the Tom Brady of its industry—performing at the top of its game at an age when its onetime peers have long since stopped playing. Here’s part of the explanation: Since its founding, Intuit has done what every company today must learn to do, disrupting itself continuously, reinventing its products and its business model before any competitor can beat it to it. The company’s original product, Quicken personal-finance software, had to be re-¬created when Microsoft Windows supplanted the DOS operating system. New products in the 1990s, QuickBooks for small-business accounting and TurboTax for personal tax preparation, defeated incumbents—and maintained their leads when Intuit re ¬created them online for the web’s earliest days. Those products had to be reconceived again at the dawn of the mobile era. It all seems obvious in retrospect, but each transformation was a mind bender at the time—doing taxes on a phone?—which Intuit achieved, avoiding the creeping danger of big-company disease. Its current self-disruption, arguably more radical than any before, began five years ago when top managers decided Intuit had to be more than a provider of products and services. It had to become an open platform. “The average small business uses 16 to 20 apps, and we make three,” explains Smith, 53, who has been CEO for 10 years. “So we had to open up our platform and trust that this would make our customers more loyal to us and also would give us insights into problems we could go solve.” The company gambled that it would become stronger, not weaker, by welcoming outside developers—potential competitors —onto an online platform where they can offer apps that work with Intuit products. Example: American Express offers a free app for holders of AmEx business credit cards that automatically transfers card transactions to the user’s QuickBooks Online account every day. It’s a selling point for American Express, and it ties QuickBooks customers more strongly to the platform by making their lives easier. |

|

开放平台策略确实奏效,目前已提供1400余款应用。Intuit也获得了意料之外的机会。举例来说,小企业成功还是失败的关键因素之一就是有没有请会计。Intuit为60万名会计提供税务软件。所以去年Intuit启动了在线匹配功能,可为会计与QuickBooks在线用户牵线搭桥。去年估计有60万家小企业客户成为会计的新客户,主要就是靠这项匹配功能。“对会计和小企业是双赢,”史密斯表示,“对我们来说,QuickBooks用户留存率增加了16个(百分)点。”这个数字相当了不起,因为启动匹配功能之前QuickBooks在线用户续订率已在75%左右。 Intuit也由此转型为行业生态系统,包括客户、应用开发者、会计师和Intuit在内的各方以全新方式合作共赢。又是一次成功的变革。 所以Intuit一直在没有危机推动的前提下颠覆自身。这不太寻常。各行各业的企业,从零售商、汽车制造商、媒体公司到财务顾问公司都在拼命适应数字时代,免得沦为下一个玩具反斗城、柯达公司或是旧金山出租车公司Yellow Cab,下场要么是破产,要么实力大为削弱,要么彻底消失。但转型举措少见成功。几乎所有面临困境的企业都制定了数字化战略,但经常转得不够彻底,要么就是执行不力。即便成功度过危机,可能也得接受规模变小,行业地位降低,雇员减少的后果。与此相反,Intuit总能抢占先机,在纷繁芜杂的当下实现低调转型,而且越走越顺。 这就让人产生巨大的疑问:Intuit到底怎么做到的?尤其如今每家公司最担心的就是不知从哪冒出来个竞争对手,彻底颠覆自己,找出Intuit成功的原因或许对所有人都有借鉴意义。在我们看来,Intuit的成功并不容易,但原因很明确,只是经常被忽视。“现有企业里没什么类似例子,” Intuit前财务主管耐德·西格尔表示,8月他离开公司去Twitter担任首席财务官。“Intuit成功的奥秘是世界上最大的秘密之一。” 为了解开这一谜团,首先得分析Intuit成立初期经历的一些重要事件。当时Intuit唯一的产品是Quicken个人财务软件,由创始人史考特·库克在1983年开发。Intuit经常向用户发放问卷,问用户是在家还是办公室使用Quicken软件。调研结果是一半在办公室使用。这不合理,库克和同事们想,也许用户是在办公时间计算账目管自己的钱。但还是感觉不对。“我们每次问这个问题,都有一半的人如此回答,”65岁的库克回忆说,他现在担任董事会执委会主席,仍然负责公司事务。“当时我很烦,为什么总有人答错问题?后来我们仔细研究了。” 库克和同事们发现真实情况相去甚远。回答在办公室使用的客户并没有算自己的账,只是在用Quicken管理小企业账目。“为什么他们要用Quicken呢?”库克忍不住想。这款软件并不是用来管理企业的,其他不少产品才是真正商用软件。结果发现其他产品只是复制了大企业会计的记账模式,而大部分小企业记账人员根本不懂复制记账法。“对大多数用户来说,所谓‘总账’像二战英雄一样遥远,”库克回忆道。“我们的产品里基本没有结算这一道。” 结果是QuickBooks只用了两个月就超过了市场上原本领先的产品(叫DacEasy),尽管QuickBooks价格贵了一倍(99美元vs49美元),功能也比对手少一半。“我们解决了一直让人头疼的大问题,”库克说。如今QuickBooks的收入占Intuit的一半。 关键在于Intuit从未放过任何反常之处。大部分企业做得刚好相反,就像库克和同事们刚开始的反应一样。他们会忽视反常的信息,或说服自己这并不重要。但Intuit就是靠着一次又一次解开奇怪现象的谜团,用Intuit管理者的话说就是“发掘惊喜”,切实做到了不断改进自身,不给竞争对手超越的机会。举例来说,Intuit发现在线资金管理服务应用Mint的一些用户并不符合目标人群的年轻专业人士。经过调查,Intuit发现这部分客户是自由职业者,用Mint管理收入和支出,比方说Uber或Lyft司机。随着共享经济崛起,Intuit也嗅到巨大的商机,因此专门开发了适合自由职业者使用的QuickBooks。现在是全公司增长最快的产品。 如果Intuit没有将用户研究透彻,就不会得出如此深刻的认识,而了解用户也是Intuit成功的另一个关键点。所有公司都声称要了解客户,但没有一家有Intuit走得近。其最有效的用户调研工具叫“跟我回家。”几位员工一同拜访客户的家和办公室(前提是获得允许),看客户如何使用产品。参与项目的员工都经过培训:不可以问客户,只能观察。拜访完成后员工们会立刻汇报,因为每个人都有自己的感悟。“这样能尽快全面了解,”史密斯解释说。“问题会变得直观起来,因为亲身体会到了。” 此举反映的现实则是,客户的说法有时不可信,但很多公司花费巨大代价才了解这点。客户的行为才是真相。 |

The open platform is working and now offers some 1,400 apps. It has also created unexpected opportunities for Intuit. For example, a major factor in the success or failure of a small business is whether it works with an accountant. Intuit has relationships with 600,000 accountants who use its tax software. So last year Intuit launched an online matchmaking feature to connect accountants with QuickBooks Online users. In the past year an estimated 600,000 small-business customers have become new clients of accountants, thanks in large part to this feature. “That’s a huge win-win for both of them,” says Smith, “and for us it increases the retention of QuickBooks by 16 [percentage] points.” Which is saying something, because the pre-matchmaking customer renewal rate for QuickBooks Online was around 75%. Intuit thus is becoming an ecosystem in which several parties—customers, app developers, accountants, and Intuit—find new ways to interact for mutual benefit. Another reinvention. The recurring pattern is that Intuit disrupts itself without the motivation of a crisis. That’s highly unusual. Thousands of companies across the economy—retailers, carmakers, media firms, financial advisers—are trying desperately to remake themselves for a digital world lest they become the next Toys “R” Us or ¬Kodak or San Francisco Yellow Cab: bankrupt, diminished, maybe dead. Few of those efforts will end well. Virtually all companies that get disrupted have a digital strategy; it’s usually inadequate, or they can’t execute it. Even survivors of a crisis almost always end up smaller, less significant in their industry, and employing fewer people. By contrast, Intuit preempts crises, compiling a record of prescient, low-drama transformation in a high-drama age, and thriving as a result. All of which raises the giant question: How has Intuit done it? At a time when every company’s greatest fear is being disrupted by a competitor it never saw coming, the answer holds lessons for all businesses. The key to Intuit’s success is not simple, as we’ll see, but it is clear, and it has been largely overlooked. “There’s no business quite like it,” says Ned Segal, a former Intuit finance executive who left the company in August to become Twitter’s CFO. “Intuit is one of the best-kept secrets on the planet.” To unravel the secret, start with a crucial event in the company’s early days. Its only product was Quicken personal-finance software, which founder Scott Cook had created in 1983. Intuit surveyed customers regularly, asking them among other things whether they used Quicken at home or in the office. Half said in the office. That made no sense, but Cook and his colleagues figured they were using office time to balance their checkbooks and manage their own money. Still, something seemed wrong. “Every time we asked that question, half said the same thing,” recalls Cook, 65, who now chairs the board’s executive committee and is still active at the company. “It just bugged me. Why were people answering that question wrong? So finally we dived in.” Cook and company discovered they were way off base. Those customers weren’t balancing checkbooks: They were using Quicken to run small businesses. “But why were they using Quicken?” Cook wondered. It wasn’t designed for businesses, while dozens of other software products were. It turned out the other products replicated big-company accounting—and most small-business bookkeepers knew nothing about double-entry bookkeeping. “For most of them, ‘general ledger’ was a World War II hero,” Cook recalls. “So we built an accounting product that didn’t seem to have any accounting.” The result was QuickBooks, which passed the market leader (called DacEasy) in just two months, even though QuickBooks cost twice as much ($99 vs. $49) and had fewer than half the features. “But we had solved the biggest unsolved problem,” Cook says. Today QuickBooks brings in half of Intuit’s revenue. The key, which Intuit has never forgotten, was to focus on the finding that makes no sense. Most organizations do the opposite, as Cook and his colleagues did at first. They ignore the information that doesn’t fit, or convince themselves it isn’t important. Time and again, digging into the puzzling discovery —“savoring the surprise,” as Intuit’s leaders call it—has enabled the company to reinvent itself before competitors caught on. For example, Intuit recently found that some users of its online money management service Mint weren’t behaving like the young-professional target market. Investigating that surprise showed that these customers used Mint to manage self-employment income and spending; many were Uber or Lyft drivers, for example. With the gig economy growing, Intuit recognized a huge opportunity. So it created a version of QuickBooks especially for the self-employed. It’s the company’s fastest-growing product. These critical insights never would have happened if Intuit hadn’t been studying its customers rigorously—another vital element of its success. All companies claim they want to get close to their customers, but few do it as obsessively as Intuit. Its most effective tool is the “follow-me-home.” A few employees together visit a customer’s home or office (with permission) and watch him or her using Intuit products. The employees are trained in how to do it: You don’t interview the customer; you just observe. They debrief immediately afterward because they all will have noticed something different, “so you get a complete picture much faster,” Smith says. “It puts a face to a problem. You see the humanity.” The underlying reality is that you can’t believe what customers tell you, as most companies learn the hard way. Customer behavior is the truth. |

|

“跟我回家”项目历史也很悠久。早期用户打电话抱怨的软件问题,都是之前Intuit找用户在办公室内测时没碰到过的。库克感觉哪里不对,但不知道怎么才能弄清。后来他读到《华尔街日报》上一篇文章,内容是美国房东起诉国外汽车制造商。原告出租家中房间给附近大学的学生,结果发现所谓的“学生”都是汽车制造商的员工,他们住下是为了观察美国人如何使用自家造的车。看到这诡异招数后,库克脑中冒出了一个好主意。“我们找了本地的电脑商店,只要卖出我们的产品,里面都夹上一张纸条,写着‘我们希望亲眼看您打开包装使用软件’”,然后观察接下来的情况,由此诞生了“跟我回家”项目。现在Intuit每年花在拜访客户上的时间约有1万小时,即便史密斯每年也会花60到100小时亲自拜访客户。“去客户家得到的信息跟看数据资料完全是两回事,”他表示。“一定要看着客户的眼睛,感受他们的情绪。” 好了,Intuit非常在意与客户接触,而且非常擅长观察反常现象。这些确实是很重要的优势。但这毕竟是庞大的业务,而且每位黯然下台的首席执行官都心知肚明,业务越庞大就越没有动力改变现状。因此Intuit制定了非常聪明的管理机制,一旦出现反对变革的声音就及早摁住或打消念头。具体方案包括: 小团队。新想法最初由“探索小组”开发,一般只有三名成员。小组不用遵循正常的汇报链,可以直接向部门总经理报告。每过一到两周总经理或库克会亲自培训团队成员,如果遇到极力维护现状的人,可以勇敢发声反对。新的自由职业者版QuickBooks就是由探索小组开发的。 分享经验。新想法产生后,分享经验经常可以有效减少冲突。六七年前,史密斯希望Intuit将重点转向移动设备时就受到一些管理者极力阻挠,他们还是死守着人们不会用移送设备管钱的老观点。Intuit找到一些通过移动互联网赚到很多钱的公司,要求反对的管理者去采访别人家的高管,然后立刻汇报感悟。“结果时间不够用,”库克说。“他们根本停不下来。每个人都在拼命说服别人移动设备软件可以赚钱。”如今只要打开TurboTax就能在手机上填好整套1040税表。 分享数据,迅速决策。“以前我开员工会议,参会的就是我和12位直接下属,”史密斯表示。“现在我们每月会将会议内容发给400位高层,24小时内他们要向8200位员工传达会议精神。”如果所有人都知道高层领导在忙什么,为什么要这么做,就会减少很多内耗。决策会更迅速,遇到冲突时Intuit会采取日落原则:如果24小时内无法解决,就在下个24小时内将问题上报高层决策。“我们要做最终决定并承担责任,”史密斯表示。“如果错了,我们就从错误中学习,继续前进。” 其实这些管理原则应用起来很简单,任何公司明天都能做到,至少理论上可以。最难应用的一点,或许也是对Intuit不断自我颠覆获得成功最重要的是勇于革新的公司文化。关键一点是勇敢承认错误,容忍不足,允许失败,这些在两方面格外重要。 首先,一家企业既然要改,也就等于承认存在不足之处。企业都不愿承认。如果有地方做得不好,就得有人受罚,是吧?如果没人愿意担责,那就永远没法变革。只有管理层经常承认错误,才能铺平变革的道路。2009年,史密斯刚担任首席执行官一年时,他主持过一场100人参加的晚宴,在场的都是工程师或产品设计师,其中也有别家公司的人。“布拉德发表讲话时说,‘有好些事我都弄砸了,’”库克回忆说。“很难想象别家首席执行官说出这种话。”2015年Intuit旗下桌面产品TurboTax宣布提价,引起用户不满。业务负责任苏珊·古达兹表示,“‘决定是我做的。我没想到引起这么大反响,向所有人抱歉。以下是我们这么做的原因,’”一位亲历者回忆所。“道歉的影响很大。”如今古达兹仍然在Intuit工作,而且是冉冉新星。每家公司都声称要从错误中学习,不会施加惩罚,但很少能说到做到。 第二个好处便是打造开放且开诚布公的企业文化。还记得史密斯办公室墙外的业绩评估和反馈报告么?此举就是史密斯宣布自己要改变的宣言。如果高层领导都承认要改正不足,其他人就很难坚称自己或任何业务都完美无缺。 随着Intuit业绩持续走高,放手让公司自然发展的想法日渐受欢迎。但Intuit也要清醒面对风险。最大的风险是数据泄露。用户使用TurboTax和QuickBooks时,Intuit会知道社保账号、银行账户,还有子女姓名之类隐私信息。最近研究机构Ponemon Institute的调查显示,Intuit在隐私信任公司榜单中排名第八,排在惠普后面,但高于PayPal。这是巨大的竞争优势,但一旦出现大规模泄露事件可能瞬间消失。 虽然Intuit在行业里占据优势地位,但竞争对手并未放弃。最大的竞争对手是总部位于新西兰的Xero,是一家专门服务小企业会计业务的创业公司。对于Intuit主导的美国和加拿大市场来说只是很小的因素。问题在于,Intuit在美加之外的市场里只是小因素。Intuit在全球化方面动作很慢,由于其软件可以通过云提供服务,目前在180个国家拥有少量客户。但其他大部分地区对竞争对手来说仍是机会,而且Intuit的品牌只在北美地区很强,在其他地区并不够知名。 还有个风险,可能比较小,就是美国国税局也可能变成竞争对手。2003年Intuit和其他几家软件公司与国税局达成协议,由软件公司向低收入纳税人提供免费的税务申报和填写服务;条件是国税局承诺不提供纳税软件。这项协议2020年10月即将到期。一想到要用国税局官方软件,大多数纳税人都会感觉不寒而栗,但跟国税局作对的后果显然更恐怖,届时数百万人可能要被迫使用官方软件。 目前Intuit也在谨慎地探索下一次转型机遇。去年秋天开始,Intuit召集了70位业务负责人分成小团队,分别探索与用户交互和科技领域相关的八大重要趋势——10岁以下用户如何使用科技、会话用户界面、人工智能、区块链等等。发回的报告提出了更多值得探索的领域,目前按照Intuit风格调研的共有23个。据史密斯介绍,“通过500次‘跟我回家’项目,访问了从风投基金大佬马克·安德森到爱彼迎和Uber创始人,还在五大洲进行了100项试验。” 若论起下一次颠覆到来之前就积极应对,再没有比Intuit更积极的了。因为Intuit深谙在数字世界里没有最终的成功,却有大把一败涂地的例子,而成功总是很脆弱。这就是为何一家科技老兵能牢牢占住《财富》未来50强的真正原因。库克说,现在Intuit探索23个领域其实没什么新鲜举动,只是按一贯风格行事而已。“只是又一次在必须改革之前找出机会而已。”(财富中文网) 译者:Charlie 审校:夏林 本文另一版本将发表于2017年11月1日出版的《财富》杂志。

|

The follow-me-home also has deep roots. Early customers were calling to complain of problems that hadn’t shown up when Intuit brought users into its offices to test software. Cook realized he was missing something but didn’t know how to find it. Then he read a Wall Street Journal article about American homeowners suing a foreign automaker. The plaintiffs had rented rooms in their homes to students at nearby universities, only to find that the “students” were actually employees of the automaker whose purpose was to observe how Americans use their cars. In this creepy tactic, Cook saw the kernel of a great idea. “We went to a local computer store, and every time they sold one of our products they included a note from us saying, ‘We’d like to come watch you take the shrink-wrap off the product’ ”—and then observe what follows. Thus was born the follow-me-home. Today Intuit conducts some 10,000 hours of these visits annually. Smith himself does 60 to 100 hours a year. “What you get from a follow-me-home you can’t get from a data stream,” he says. “You’ve got to look somebody in the eye and feel the emotion.” So Intuit obsesses over customer intimacy, and it has trained itself to embrace anomalies. Those are major strengths. But still, this is a big, successful business, and as every deposed CEO knows, that creates incentives to reject any change to the established order. Intuit therefore deploys clever managerial techniques to evade or defeat the organizational change-killers. Among them: Tiny teams. New ideas are initially developed by “discovery teams,” typically only three people. They don’t report up the chain of command but instead go straight to a division general manager. The teams get intensive coaching every week or two from the GM or Cook, which helps them stand up to the barrage of opposition they’ll inevitably face from those with a stake in the status quo. The new self-employed version of QuickBooks was developed by a discovery team. Shared experiences. When new ideas get further along, shared experiences can often obliterate conflicts. Six or seven years ago, when Smith wanted Intuit to focus on mobile devices, stiff pushback came from managers who believed the then-conventional view that no one makes money on mobile. So Intuit found companies that were making plenty of money on mobile and assigned managers to interview their executives. Next step was an off-site where they would report what they learned. “We didn’t have enough time,” Cook says. “They wouldn’t stop. They were convincing each other there was money to be made in mobile.” Today, using TurboTax, you can prepare and file a full 1040 from your phone. Shared data, fast decisions. “My staff meeting used to be just me and my 12 direct reports,” says Smith. “Now we broadcast it to our top 400 leaders every month, and they have 24 hours to cascade it to all 8,200 employees.” A lot of infighting disappears when everyone knows what the top leaders are doing and why. Decisions get made much faster, and when a conflict arises, Intuit follows a sunset rule: If you can’t resolve it in 24 hours, you get another 24 hours to escalate it high in the organization to get a decision. “We’re just going to make the call and live with the consequences,” Smith says. “If it’s wrong, we’ll learn from our mistake and move on.” Any company could adopt those managerial techniques tomorrow, at least in theory. Far more difficult to adopt, and perhaps more important to Intuit’s self-disruptive success, is a culture that facilitates reinvention. A key element is permission to admit mistakes, shortcomings, and failures, which is valuable in two ways. First, when an organization tries to change, it is implicitly admitting something isn’t working. No organization wants to admit that. People get punished when something isn’t working, right? And if no one will go there, change is forever blocked. Change gets unblocked when top managers routinely admit their mistakes. In 2009, when Smith had been CEO for a year, he presided over a dinner for about 100 people in engineering and product design, including some from other companies. “Brad gave a talk and said, ‘Here are the things I screwed up on,’ ” Cook recalls. “It was hard to imagine any other CEO giving that talk.” In 2015 the company raised prices on its desktop TurboTax products, and customers revolted. The business’s leader, Sasan Goodarzi, said, “ ‘I own this decision. I had no idea this would happen, and I’m sorry to you all. Here’s why we did it,’ ” reports a witness. “It made a big impact.” Goodarzi is still at Intuit and widely considered a rising star. Every company says it wants to learn from mistakes, not punish them, but few companies live that way. The second advantage of an open, fess up culture is subtly different. Remember those performance reviews and feedback reports taped up outside Smith’s office? They’re Smith’s proclamations that he himself must change. When top leaders admit that they must fix their flaws, it’s hard for others to claim that they or their business unit are beyond improvement. The temptation to leave things alone is powerful right now, with Intuit performing so well. Yet the company faces sobering risks. The most obvious is a data breach. If you use TurboTax and QuickBooks, Intuit knows your Social Security number, your bank account numbers, your credit card numbers, everything about your brokerage accounts, and your children’s names, among other things. Consumers rank Intuit No. 8 among all companies for privacy trustworthiness in the latest survey by the Ponemon Institute research firm, just behind HP and ahead of PayPal. That’s a titanium-strength competitive advantage, but it could vaporize after a major break-in. Though Intuit utterly dominates its fields, competitors aren’t giving up. Its most credible competitor is Xero, a New Zealand–based small-business accounting startup. It’s a minor factor in the U.S. and Canada, where Intuit rules; trouble is, Intuit is a minor factor in the rest of the world. Intuit is belatedly going global, and because its software is available as a service in the cloud, it has at least a few customers in 180 countries. But most of the planet remains wide open to competitors, and Intuit’s brands aren’t nearly as strong abroad as they are in North America. There’s even a danger, probably small, that the IRS might become a competitor. Intuit is one of several software companies that in 2003 agreed with the IRS to provide free tax prep and filing for low-income taxpayers; in return, the IRS promised not to offer tax software. That agreement expires in October 2020. The very thought of IRS software probably makes most taxpayers’ blood run cold, but since the prospect of crossing the IRS is even scarier, millions might opt to use such a product. Intuit, in its disciplined way, is sending scouting parties in search of the next big transformation. Starting last fall, the company grouped 70 of its leaders into small teams and told them to investigate eight major trends that arose in customer interactions and tech forums—how consumers under age 10 use technology, conversational user interfaces, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and more. Their reports sparked still more topics to pursue, all of which—23 in total—have now been investigated Intuit-style, as Smith details: “through 500 follow-me-homes, 225 interviews with everyone from Marc Andreessen to the founders of Airbnb and Uber, and 100 experiments conducted across five continents.” No company tries harder to find the next big disruption before it finds them. Intuit understands that in the digital world there are no final victories but plenty of final defeats, and success is always tenuous. That’s how a tech oldster lands on the Future 50. As Cook says, Intuit’s current 23-topic initiative is nothing new. It’s what the company does. “It’s another opportunity to change before it’s needed.” A version of this article appears in the Nov. 1, 2017 issue of Fortune. |