这位传奇投资人在这两家传奇企业的身上栽了跟头

|

今年10月1日,通用电气宣布解雇仅就职14个月的首席执行官约翰·弗兰纳里,鲜少有人不对此感到震惊,但大名鼎鼎的激进投资者纳尔逊·佩尔茨就是其中之一。甚至连一直执着于跟踪这家风光不再的企业动态的华尔街分析师都因为弗兰纳里的突然被炒而感到惊讶。然而佩尔茨对此并非事先不知情,因为他在特里安对冲基金的合伙人爱德华·加登是通用电气的董事会成员,正是董事会炒了弗兰纳里。特里安拥有7100万股通用电气股票,通用电气也因而成为佩尔茨多年来十分成功的职业生涯中损失最惨重的投资。由于该公司最近披露的负债据说受到了联邦刑事调查,公司股票再度下跌,佩尔茨持有的股票和三年前买入时相比,已经亏损逾10亿美元,跌幅达约50%。随着弗兰纳里迅速遭到无情抛弃,佩尔茨明白变化正在酝酿中。 佩尔茨比大多数人都更能适应巨变。所谓激进投资人指的是不满足于袖手旁观的投资人,而在这类投资者中,佩尔茨在推动变化方面也是佼佼者。作为激进派投资者,他曾对多家公司发起过突袭,包括推动杜邦在与陶氏化学合并后再分拆为三家独立公司。他还促使卡夫分为卡夫食品集团和亿滋国际。他试图拆分百事可乐,但失败了。这是一位野心勃勃的投资人。 但在他诸多野心勃勃的计划中,对通用电气和位于其待办事项清单顶端的另一家公司宝洁的野心可谓最大。宝洁没有失败,因为自佩尔茨投资以来,该公司的股价小幅上涨,而且它显然比通用电气更有希望。11月,宝洁宣布了重组计划,虽然是在佩尔茨一直力推的计划上打了折扣。一年前佩尔茨和宝洁打了美国历史上最昂贵的代理权争夺战,并最终在3月加入公司董事会,但该公司远未取得佩尔茨所希冀的成功。宝洁的股价上涨缓慢,佩尔茨的股权目前价值35亿美元,是价值100亿美元的特里安目前的最大投资。因此佩尔茨要想依靠宝洁摆脱通用电气崩溃带来的困境,宝洁的表现要有显著好转才行。(因为佩尔茨是宝洁的董事,而他的女婿加登是通用电气的董事,他们拒绝了本文的采访请求。) 通用电气和宝洁一同毁掉了特里安此前优秀的投资记录:过去五年,特里安的收益率高达年均11.9%,成绩不俗;过去三年,是平淡无奇的年均6.5%;据特里安的一名投资者称,截至10月,2018年的数字大约是令人沮丧的-1%。佩尔茨的大部分个人财富和高绩效激进投资人的美誉都绑在了这两家公司身上。 佩尔茨在通用电气和宝洁公司能干成什么样非常重要,因为这两家知名公司不但都是佩尔茨的大难题,还拥有许多共同点。这两家美国公司在世界各地都被誉为公司中的贵族,拥有100多年的血脉延续。两家公司又都拥有各自独特又不容改变的企业文化,而且这些文化都形成于公司在市场上独领风骚的时期。但它们又都已经风光不再。依靠在两家公司的董事会席位,特里安正不断尝试突破它们的界限,试图实现更大目标。除了利用分拆、削减成本、借贷等激进投资者常用的工具,特里安和其他激进投资人相比,更愿意深入钻研公司运营,有时他们会花费数年时间帮助公司管理层解决经营问题。由于采取颠覆性措施对老牌大公司产生更大的威胁,所以特里安能否在通用电气和宝洁实现成功可以帮助我们判断,如果激进投资人或任何局外人想要改变曾经统治世界的公司,在这种最高难度的经营难题中他们可以取得多少成绩。 |

On Oct. 1, when General Electric announced it had fired John Flannery, its CEO of just 14 months, one of the few people not at all shocked by the news was Nelson Peltz, the legendary activist investor. Flannery’s abrupt dismissal surprised even Wall Street analysts who obsessively follow the tarnished conglomerate. Yet Peltz wasn’t caught off guard, because his partner at the Trian hedge fund, Edward Garden, is on the GE board of directors that did the deed. Trian owns 71 million shares of GE stock, qualifying GE as Peltz’s most disastrous investment in a long, successful career. He’s down over $1 billion, about 50%, since buying in three years ago, with the stock’s latest drop following word of a federal criminal investigation into recently disclosed liabilities. With the brutally swift cashiering of Flannery, Peltz now understood change was afoot. More than most, Peltz is comfortable with dramatic change. No other activist, a class of investors not content merely to watch from the sidelines, has prompted more of it. Among many activist forays, he instigated the transformation of DuPont into three independent companies after first combining with Dow Chemical. He forced the separation of Kraft into Kraft Foods Group and Mondelez International. He tried and failed to break up PepsiCo. He thinks big. He has never thought bigger than he did with GE and with the other company at the top of his to-do list, Procter & Gamble. P&G is no disaster—its shares are up slightly since Peltz invested—and it’s decidedly more promising than GE. In November, the company announced a watered-down version of the reorganization plan he had been pushing. But the company is nowhere near the success Peltz wants it to be, a year after he battled P&G in the most expensive proxy fight in U.S. history and gained a board seat in March. P&G stock is a laggard, and Peltz’s stake, recently worth $3.5 billion, is by far the biggest investment in $10 billion Trian. So Peltz needs it to perform much better if it’s to help rescue him from the GE debacle. (Because Peltz is on the P&G board, and Garden, his son-in-law, is on the GE board, they declined interview requests for this article.) Together, GE and P&G have mauled Trian’s previously sterling record: Over the past five years, Trian’s rate of return has averaged an outstanding 11.9% annually; over the past three years, a mediocre 6.5% annually; in 2018 through October, a dismal –1% or so, according to a Trian investor. Much of Peltz’s personal wealth and his reputation as a high-performing activist are tied up in those two companies. How Peltz fares with GE and P&G is important because the two famed companies share many traits besides being Peltz’s biggest problems. They’re American institutions, storied worldwide as corporate aristocrats with bloodlines stretching back more than a century. Each lives according to a unique, titanium-strength corporate culture that developed back when they were supremely dominant. Neither company has retained its stature, though. With board seats at both, Trian is pressing the boundaries of what can be accomplished at such organizations. In addition to bringing the activist’s usual tools—breakups, cost cutting, borrowing—the firm is willing to delve more deeply into operations than any other activist and sometimes spends years helping management fix a business. As disruption threatens more big, old incumbents, Trian’s success or failure will help define how much an activist, or any outsider, can hope to achieve in that hardest of managerial challenges, transforming a company that once ruled the world. |

|

佩尔茨不是一般的激进投资人,特里安也不是一般的对冲基金,通用电气也不是特里安的一般投资。现年76岁的佩尔茨将他的激进投资历史追溯至20世纪80年代中期迈克尔·米尔肯以及他资助的一票企业狙击手的鼎盛时期。 除了佩尔茨,还包括卡尔·伊坎、索尔·斯坦贝克、T·布恩·皮肯斯等。与当时的许多人不同,佩尔茨对所谓的绿票讹诈不感兴趣,这种战术指的是大量购买公司股票,威胁管理层要收购公司、迫其失业,表示如果公司高价回购绿票讹诈者所持股票就会离场。佩尔茨看到了能赚更多钱的机会。 他觉得自己能成功,因为不同于20世纪80年代的其他狙击手,也不同于今天的激进投资人,他曾经在远离华尔街的地方做过生意。他和他的兄弟将家里的食品分销业务做成了一家名为弗拉格斯塔夫(Flagstaff)的冷冻食品公司;直到今天,特里安仍然热衷于食品企业,并投资了多家食品公司,如Wendy’s、卡夫、亨氏、百事可乐等等。佩尔茨40岁时,弗拉格斯塔夫公司破产了,但他显然从中学到了教训。他和曾担任弗拉格斯塔夫首席财务官的会计师彼得·梅收购了Triangle Industries,这家自动售货机和电线公司被他们打造成了全球《财富》100强工业集团,后来在1988年被卖出。从那之后,佩尔茨和梅就一直在从事收购公司、进行业务修复再卖出公司的营生。2005年,他们和第三个合伙人、曾任瑞士信贷第一波士顿公司(Credit Suisse First Boston)投资银行家的加登共同创立了特里安。据特里安表示,曾在佩尔茨和杜邦及宝洁的代理人之争中为其提供支持的加州教师退休基金(State Teachers’ Retirement System)及其他机构投资者占公司全部资产的75%。 “采取修复措施,让公司经营好转——这就是我们的工作。”57岁的加登在3月的一次投资会议上说。“我们寻找的公司在本质上都是伟大的公司,虽然管理层在运营方面偏离轨道,但我们相信自己知道如何让他们的业务重回正轨。”如果你觉得这听起来更像是私募股权,特里安也同意这种看法。“我们认为自己是一种新的资产类别,”他说。“可以称为‘流动型私募股权’或‘混合型私募股权’。”特里安的目标是获得和私募股权同等规模的回报,但不必像私募公司那样买下整个公司或大额股份。特里安仅拥有宝洁公司1.5%的股份和通用电气公司0.8%的股份。通过改善目标公司运营,长期持有目标公司股权,特里安即使不使用杠杆,也能够获得更高收益,比仅仅依靠交易赚取更高的绩效费。 2015年春天,特里安成功结束了四项投资——达能、家庭美元百货(Family Dollar)、英格索兰(Ingersoll-Rand)和拉扎德(Lazard),准备开展其它投资项目。通用电气公司显然符合特里安的投资标准——一家脱离了轨道的伟大公司,而且碰巧,时任通用电气公司首席执行官的杰夫·伊梅尔特邀请佩尔茨买进公司股份。两年前,伊梅尔特甚至安排佩尔茨向公司顶级管理人员讲授如何削减成本。这种开放的欢迎态度几乎闻所未闻:通常情况下,特里安的目标公司会试图击退入侵者,至少在最初阶段会是如此。巨大的老牌工业公司不是佩尔茨的专长,但重点是伊梅尔特向华尔街承诺,通用电气将在2018年实现每股盈利2美元,而2015年的持续性经营每股收益仅为17美分。特里安认为通用电气甚至能表现更好,能实现2.20美元或以上的盈利;当时26美元的股价在2017年年底应该达到40到45美元之间。佩尔茨购买了23亿美元的通用电气股票并告诉伊梅尔特,特里安将确保他能够实现每股2美元收益的承诺。 当年秋天,特里安发布了通用电气“白皮书”,这份81页的PPT对通用电气的战略和股票都提出了有力支持。的确,公司需要降低成本、削减管理层,而且可以增加借贷。但本质上,这不过是伊梅尔特“大幅改变其商业模式”的一个例子——大幅剥离GE金融业务,从公司的服务业务而非销售中获得收入——特里安认为这“在市场上未得到充分重视”。之后股价上涨,佩尔茨卖出了一些,撤出了近4亿美元的资金,事后回想这实在是明智之举。公司股票继续上涨,达到金融危机前未曾企及的高度,于2016年12月冲上32.38美元。 让人头疼的担忧首先出现在2016年第四季度。通用电气的转型十分昂贵:该公司支付的现金超过了收入,其养老基金短缺310亿美元。仅2015年支付的股息就高达93亿美元,比通用电气的全部净现金流都要多。此外,通用电气最大的业务是为电力企业提供巨型涡轮机,相关订单量却未达预期。不过,这种和期望值之间的差距可以说成是可逆的,投资者似乎并不担心。 如果当时佩尔茨对通用电气感到担心的话,他似乎不太可能在那个时刻对另外一个陷入麻烦的巨人再下高额赌注。就在几个星期前,随着他的通用电气股价升值,佩尔茨买入了首批宝洁股票。截至2017年年初,这是特里安新近投资中最大的一笔,价值33亿美元。尽管宝洁不再从事佩尔茨最喜欢的食品生意,却仍然是他的理想目标——一家伟大却架构过于复杂、需要整顿的公司。宝洁旗下包括吉列剃须刀、佳洁士牙膏、潘婷洗发水在内的数十个最知名品牌正在失去市场份额;全部五个产品类别都失去了竞争优势。公司的其他投资者很高兴看到佩尔茨出手,这只在牛市都停滞多年的股票在佩尔茨入场后一度飙升。 华尔街喜迎佩尔茨,但宝洁公司的领导层却并不欢迎他的加入。该公司发布声明,感谢全体股东,但管理层想到未来要由外人对他们指手画脚便感到深恶痛绝。佩尔茨与首席执行官戴维·泰勒以及董事会的会议令双方都备感沮丧。2017年6月,有消息说佩尔茨提名自己担任公司董事时,投资者一片欢呼,股票再次大涨。但颇为讽刺的是,宝洁公司的领导层日后却把当时股票行情的好转当成证据,证明不需要佩尔茨的帮助他们的战略也行之有效。 佩尔茨的请求遭到了宝洁的拒绝,所以他在7月宣布开启代理权争夺战。事实证明,这种斗争费时费钱,令各方都感到不快。泰勒警告道,佩尔茨分散了管理层的注意力,会“拖累管理层正在领导公司进行的转型。”佩尔茨一再公开点名攻击泰勒,并邀请前宝洁公司首席财务官克莱顿·戴利加入其阵营讨伐戴利的前雇主。双方在这场战斗中花费巨大,高达1亿美元,最终,宝洁在两个月的股东投票中以50.01%比49.99%险胜,但二者的差距小到几乎可以忽略。董事们意识到他们的胜利实在太过微弱,没有足够立场拒绝佩尔茨的请求,因此他在今年3月加入了宝洁董事会。 很难相信佩尔茨和加登在史上最大的代理权争夺战之外还可以关注其它事情,但他们必须得关注。正在2017年中他们和宝洁的关系恶化时,通用电气垮掉了。 投资者们迅速失去信心,2018年每股2美元的盈利承诺显然无法实现了。(今天华尔街预计通用电气的每股收益为68美分。)通用电气投资者和分析师还能记起他们意识到伊梅尔特已经完蛋了的那一刻。那是2017年5月,长期担任公司首席执行官的伊梅尔特在佛罗里达州举办的年度集会上发表了讲话,该集会旨在为大型电子产品公司的首席执行官与金融界进行交流提供平台。“我从来没有见过那样的场景,”有人说。“他已经绝望了。你无法忍受直视他的眼睛。最简单的基本问题就能把他生生吃掉。” 仅19天后,伊梅尔特宣布退休,让所有人都大吃一惊。公司股票当天用20个月内的最佳表现对该新闻做出了回应。 |

Peltz isn’t a usual activist, Trian isn’t a usual hedge fund, and GE isn’t a usual investment for it. At age 76, Peltz traces his activist roots to the mid-’80s heyday of Michael Milken and the band of corporate raiders he financed. Besides Peltz, they included Carl Icahn, Saul Steinberg, T. Boone Pickens, and others. Unlike many back then, Peltz wasn’t interested in greenmail, the strategy of buying a stake, threatening management with a takeover that would cost them their jobs, and offering to go away if the company bought back the greenmailer’s stock at a higher price. Instead, he saw a chance to make even more. He felt he could do it because, unlike virtually all the other 1980s raiders and today’s activists, he had run businesses far from Wall Street. He and his brother built the family’s food distribution business into an institutional frozen food company called Flagstaff; to this day, Trian likes food companies and has invested in many—Wendy’s, Kraft, Heinz, PepsiCo, and more. Flagstaff went bankrupt when Peltz was 40, but he apparently learned from the experience. He and Peter May, an accountant who had been Flagstaff’s chief financial officer, bought Triangle Industries, a vending machine and wire company that they built into a Fortune 100 industrial conglomerate, which they sold in 1988. He and May have been buying, fixing, and selling companies ever since. In 2005, they formed Trian with a third partner, Garden, a former Credit Suisse First Boston investment banker. Institutional investors like the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, which has backed Peltz in his proxy fights at DuPont and P&G, account for about 75% of Trian’s assets, the firm says. “Fix companies and turn businesses around—that’s what we do,” Garden, 57, told an investment conference in March. “We look for fundamentally great companies where management has gone off track operationally and where we think we understand what it takes to get the business back on track.” If that sounds to you more like private equity, Trian agrees. “We think of ourselves as a new asset class,” he said. “ ‘Liquid private equity’ or ‘hybrid private equity.’ ” The objective is to earn PE-scale returns without having to buy a whole company or a significant stake, as PE firms typically do; Trian owns only 1.5% of P&G and 0.8% of GE. By improving operations and holding positions for years, even without leverage, Trian hopes to generate higher returns and earn bigger performance fees than it could through trading alone. In the spring of 2015, Trian was successfully exiting four investments—Danone, Family Dollar, Ingersoll-Rand, and Lazard—and was ready to invest elsewhere. General Electric certainly met the spec of a great company that had gone off track, and as it happened, GE chief Jeff Immelt had invited Peltz to buy in. Two years earlier, Immelt had even arranged for Peltz to address his top managers on the subject of cost cutting. Such an embrace was almost unheard of; Trian’s targets usually try to repel the invader, at least initially. Giant, old industrial companies weren’t Peltz’s specialty, but Immelt, crucially, had promised Wall Street that GE would earn $2 a share by 2018, up from 17¢ per share from continuing operations in 2015. Trian concluded GE could do even better, $2.20 or more; the $26 shares ought to be worth $40 to $45 by the end of 2017. Peltz bought $2.3 billion of GE stock and told Immelt that Trian would hold him accountable for keeping the $2-a-share promise. That fall, Trian published a “white paper” on GE, an 81-page PowerPoint deck powerfully endorsing GE’s strategy and its stock. Yes, the company needed to cut costs and excise management layers, and it could borrow more. But this was fundamentally a case of Immelt making “a massive change in its business model”—exiting most of GE Capital and targeting more revenue from services rather than from sales—that was “under-appreciated in the market,” Trian argued. The stock rose, and Peltz sold some, taking almost $400 million off the table, which in retrospect was a wise move. The stock continued drifting up, reaching heights it hadn’t achieved since before the financial crisis and touching $32.38 in December 2016. Nagging doubts first appeared in 2016’s fourth quarter. GE’s transformation was expensive; the company was paying out more cash than it was taking in, and its pension fund was underfunded by $31 billion. Dividend payments alone, at $9.3 billion in 2015, consumed more than GE’s entire free cash flow. In addition, GE’s biggest business, which makes gigantic turbines for electric utilities, wasn’t booking as many orders as anticipated. Still, the shortfall was arguably reversible, and investors didn’t seem worried. Had Peltz been worried about GE, it seems unlikely he would have picked that moment to make another massive bet on a troubled titan. Just weeks earlier, with his GE stake appreciating, Peltz bought his first tranche of Procter & Gamble stock. By early 2017, it was Trian’s new largest investment, worth $3.3 billion. P&G no longer marketed food, Peltz’s favorite business, but this was still his ideal target, a great company that had grown far too complex and needed shaking up. Dozens of its most famous brands—including Gillette razors, Crest toothpaste, and Pantene shampoo—were losing market share; all five of its product categories had lost significant ground to competitors. Other investors were glad to see Peltz; the stock, which had gone nowhere for years while the market surged, jumped on Peltz’s entry. Wall Street gladly greeted Peltz’s arrival, but P&G’s leaders did not. The company issued the obligatory statement about appreciating all its shareholders, but managers loathed the prospect of an outsider telling them how to do things. Peltz’s meetings with CEO David Taylor and the board frustrated both sides. When word leaked in June 2017 that Peltz had nominated himself for a board seat, investors cheered, and the stock jumped again. Ironically, P&G leaders would later cite the stock’s improved performance as evidence that their strategy was working fine without Peltz’s help. P&G rejected Peltz’s request, so in July he announced a proxy fight. The ordeal proved expensive, nasty, and long. Taylor warned that by distracting management, Peltz could “derail the transformation we’re leading.” Peltz repeatedly attacked Taylor by name and enlisted former P&G CFO Clayton Daley to campaign against his former employer. The two sides spent lavishly, as much as $100 million, on the battle, and in the end, P&G won a two-month shareholder vote by the nearly invisible margin of 50.01% to 49.99%. The directors realized the victory was too narrow to deny Peltz a seat, and he joined the board this past March. It’s hard to believe that Peltz and Garden could have focused on anything besides the world’s all-time biggest proxy fight, but they had to. Just as relations with P&G were deteriorating in mid-2017, GE was melting down. Investors were fast losing faith, and it was becoming apparent that the $2-a-share earnings promise for 2018 wasn’t achievable. (Today Wall Street expects GE earnings of 68¢ per share.) GE investors and analysts recall the moment they realized Immelt was through. It was the longtime CEO’s presentation at an annual May ritual in Florida where CEOs of big companies that make electrical products speak to the financial community. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says one. “He was a broken man. You couldn’t stand to look him in the eye. He got eaten alive by basic, simple questions.” Just 19 days later, Immelt surprised everyone by announcing his retirement. The stock responded with its best day in 20 months. |

|

由于伊梅尔特的承诺彻底没有兑现,特里安关于通用电气的计划变成了一团糟,加登和佩尔茨不再只是询问有关董事会席位的情况,而是要求在董事会中取得一席。与此同时,佩尔茨在与宝洁的代理权争夺战中展示了他的凶悍。通用电气在10月让加登加入其董事会——不需要代理权争夺战。 此后,通用电气的情况一再恶化。该公司相应采取的举措中,最引人注目的是对董事会进行彻底重组,加登进入董事会后没多久董事会就开始了重组。18位董事中有一半离职——这是前所未有的叛变——被三位新董事取代,其中一位是拉里·卡尔普。这立刻引发了人们的猜测:他是不是候任首席执行官?如果是这样,背后是不是特里安在支持?该公司未就此发表评论,但在去年5月发布了一份关于本公司的情况说明书,称“三名新董事加入董事会,其中包括丹纳赫集团的前任首席执行官拉里·卡尔普”,却未提及另外两名董事的名字。有业内人士表示,卡尔普否认有出任首席执行官的想法——显然证明了存在这种可能性。 从特里安的角度来看,通用电气董事会的改革算得上是重大进展。佩尔茨进入宝洁公司董事会后,该公司也随之取得了更多进展。代理权斗争中的龃龉消失得无影无踪。“我们尊重纳尔逊·佩尔茨……并期待他以宝洁董事会成员的身份做出贡献。”泰勒在一份声明中说。佩尔茨说他“期待与泰勒紧密合作”。能看出佩尔茨正在领导变革的第一个线索是7月发布的一份证券文件,该文件披露了宝洁公司已经修改了高管的薪酬奖励计划,更多地将薪酬与个人绩效挂钩,而非公司业绩。这是典型的佩尔茨式做法,随后公司在11月进行了一次更加重大的变革,将公司重组为六个部门,赋予每个部门的负责人更多权力和更明晰的激励措施。投资者为之雀跃:宝洁公司的股票三天内上涨2.2%,同期标普500指数却下跌3%。首席执行官泰勒称其为“公司过去20年中最重大的组织变革”。 |

With Immelt’s commitment trashed and their plan for GE now a shambles, Garden and Peltz stopped asking about a board seat and started demanding one. At that same time, Peltz happened to be demonstrating his ferociousness in the proxy fight with P&G. GE added Garden to its board in October, no proxy fight needed. From then until now, GE’s news has gone from bad to worse. Its most dramatic response has been the radical restructuring of the board, a process that began soon after Garden joined. Half the 18 directors left—an unprecedented putsch—and were replaced by three new directors, one of whom was Larry Culp. Speculation followed instantly: Was he the CEO in waiting? And if so, was Trian behind it? The firm won’t comment, but it issued a fact sheet about itself last May that observed that at GE, “three new directors joined the board including Larry Culp, former CEO of Danaher,” while omitting the names of the other two. Insiders say Culp disavowed any desire to be CEO—a sure sign the possibility existed. From Trian’s perspective, the GE board revamp was significant progress. More followed when Peltz took his seat on P&G’s board. The vitriol of the proxy fight had evaporated. “We respect Nelson Peltz … and look forward to his contributions as a member of P&G’s board,” Taylor said in a statement. Peltz said he was “looking forward to working closely” with Taylor. The first hint of Peltz-led change arrived in a July securities filing disclosing that P&G had revised its incentive pay plan for top managers, tying pay more closely to individual performance and less to corporate results. That was classic Peltz, followed in November by a far more significant change reorganizing the company into six units headed by chiefs with more power and clearer incentives. Investors cheered: P&G’s stock rose 2.2% over three days when the S&P 500 dropped 3%. CEO Taylor called it “the most significant organization change we’ve made in the last 20 years.” |

|

这是佩尔茨两大蓝筹股赌局的状态:宝洁一直在挣扎,可能仍将继续挣扎下去。最近的结构性重组会有所帮助,但宝洁的问题更深层。宝洁在国内长期外奉行建立大众消费品牌的战略与如今消费者越来越青睐小众本土品牌的心理相悖。例如,Harry’s和Dollar Shave Club的流行成功挑战了吉列的市场地位,让宝洁公司大吃一惊,这对于长期引领市场的宝洁而言是全新的经历。更广泛地说,宝洁的文化可能会阻挠任何重大变化的出现。作为拥有181年历史的公司,它或许会因为太过古老而难以做出调整。 宝洁公司还存在另外一个令佩尔茨不满意的情况。佩尔茨可以充当催化剂,推动公司缓慢改善,避免出现灾难,但会存在连续多年回报都十分微薄的情况。尽管如此,一直以来,佩尔茨都甘愿花费数年时间修复其他公司(比宝洁规模小得多),这些公司最终情况都出现好转,恢复了强势表现;Wendy's是过去十年中特里安的一场胜利,是一个正面例证。至少还有希望。 对通用电气怀抱的任何希望都是佩尔茨2015年未实现愿景的部分残留。他的投资是一场巨赌,赌一家拥有120年历史的工业公司能够适应由数字技术和相关服务引领的新时代。这个想法没错,但无论是通用电气的高层还是特里安,没有人能评估通用电气的执行能力,结果证明它的执行能力很糟糕。此外,通用电气和特里安因为全球市场对发电涡轮机的需求急剧下滑被打得措手不及。特里安的疏忽可以被原谅,但通用电气不能。之后,通用电气的全部投资者都因为公司涡轮机业务和长期护理保险业务中存在的巨额负债被曝光而情绪失控。回想起来,佩尔茨实在太过依赖伊梅尔特的保证了。对一个表现一直不怎么样的CEO充满信任是个错误。 从佩尔茨与通用电气和宝洁公司合作的艰苦征程中,可以勾画出激进主义的极限所在。由于不持有控制性股权,激进投资者不能对公司的日常经营进行管理,这意味着他们总是离解决公司的深层文化问题还有几步之遥,而在充满颠覆的当今时代,许多公司都深受文化困扰。他们能期待的最佳方案是对首次执行官的决策施加影响。但真正做出转变的决定权在首席执行官手中,而不是激进投资者。这就是为什么他们的许多提案都是结构性的,大多是对公司进行重组或分解。背后的逻辑在于,新独立的业务会因为激励措施更清晰、复杂性减少、选择增多而获益,这种策略通常都能奏效。经过特里安分解的大多数公司已经证明,拆分后的公司更值钱。但这种战略不利于维持伟大的具有悠久历史的老公司。严酷的现实可能是,在某个时刻,它们将不再值得维持。 佩尔茨押在美国商界两大垂暮贵族身上的赌注继续拖累着特里安的整体表现。现在最大的问题是,在佩尔茨实现了多年令人瞩目的成功后,这会是他职业生涯的转折点,抑或只是起起落落生意场上的一个低潮。无论结果如何,我们要清楚地看到,为了能在世界上最顽固最难修复的两家公司身上创造奇迹,以修复公司为生的佩尔茨和爱德·加登已经投入了巨额赌注。 |

So here’s the state of Peltz’s duo of big blue-chip bets. P&G has been a hell of a struggle and will likely remain one. The new reorganization is a helpful structural change, but P&G’s problems go deeper. A long-standing strategy based on building mass-market national and international brands is at odds with today’s consumers who increasingly favor smaller, niche, and local brands. The rise of Harry’s and Dollar Shave Club as successful challengers to Gillette, for example, caught P&G flat-footed—a new experience for the longtime alpha-dog company. More broadly, P&G’s culture could sabotage any significant change. At age 181, it may be too old to adjust. Peltz faces another unsatisfying scenario at P&G. He could be the catalyst for slow improvement, avoiding disaster but returning puny gains over many years. Nonetheless, Peltz has been willing to spend years fixing other companies (much smaller than P&G) that eventually turned around and came back stronger; Wendy’s, a Trian triumph over the past decade, is a good example. At least there’s hope. Any hope for GE is a shriveled remnant of what Peltz envisioned in 2015. His investment was a huge gamble on a 120-year-old industrial company adapting to a new world of digital technology and related services. It was the right idea, but no one at the top of GE or at Trian could evaluate GE’s ability to execute it, which turned out to be poor. In addition, GE and Trian were blindsided by a vertiginous plunge in global demand for electricity-generating turbines. Trian could be forgiven for missing it; GE couldn’t. And then all GE investors got crushed by revelations of mammoth liabilities in the company’s turbine business and long-term-care insurance business. In retrospect, Peltz relied way, way too much on Immelt’s assurances. Putting that much trust in a CEO who had underperformed up to then was a mistake. Peltz’s odyssey with GE and P&G outlines the limits of activism. As investors with non-controlling stakes, activists can’t run a company day-to-day, which means they’re always a couple of steps removed from solving the deep cultural problems afflicting many companies in an age of disruption. Influencing the choice of the CEO is about the best they can hope for. But the real transformation is in that person’s hands, not in the activists’. That’s why so many of their proposals are structural, mostly for reorganizing or breaking up the company. The logic is that newly liberated business will benefit from clearer incentives, less complexity, and more options, and that strategy has often worked. Most of the companies that Trian has broken up have proved more valuable in pieces. But it isn’t a strategy that preserves great old institutions. The hard reality may be that at a certain point, they aren’t worth preserving any longer. Peltz’s wager on the aging aristocracy of American business continues to wallop Trian’s performance. The great question now is whether this is a turning point for him after years of standout success or just a low point in a business full of ups and downs. As an answer plays out, the sobering truth is that he and Ed Garden, who fix companies for a living, have staked a great deal on working wonders at two of the most fix-resistant companies in the world. |

***

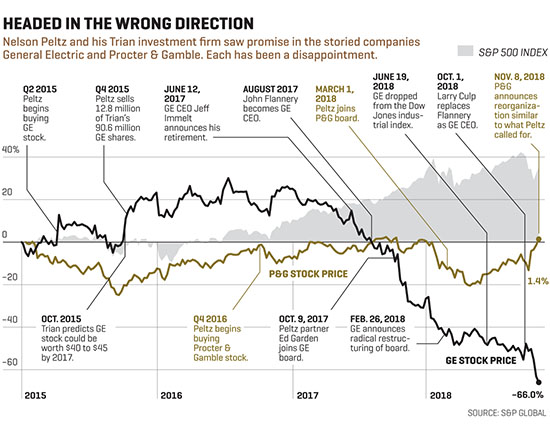

朝着错误的方向前进

纳尔逊·佩尔茨和他的特里安投资公司认为著名的通用电气和宝洁公司都有可观前景。但两家公司都令他失望了。

2015年第二季度:佩尔茨开始买入通用电气股票。

2015年10月:特里安预测通用电气股价能在2017年达到40至45美元。

2015年第四季度:佩尔茨从特里安所持9060万美元通用电气股票中出售1280万。

2016年第四季度:佩尔茨开始买入宝洁股票。

2017年6月12日:通用电气首席执行官杰夫·伊梅尔特宣布退休。

2017年8月:约翰·弗兰纳里出任通用电气首席执行官。

2017年10月9日:佩尔茨合伙人加登进入通用电气董事会。

2018年2月26日:通用电气宣布董事会洗牌。

2018年3月1日:佩尔茨加入宝洁董事会。

2018年6月19日:通用电气被道琼斯工业指数除名。

2018年10月1日:拉里·卡尔普取代弗兰纳里成为通用电气首席执行官。

2018年11月8日:宝洁宣布类似于佩尔茨提出的重组计划。

***

|

(财富中文网) 本文的另一个版本作为《2019年投资者指南》的一部分刊载于2018年12月1日的《财富》杂志。 译者:Agatha |

A version of this article appears in the December 1, 2018 issue of Fortune, as part of the “2019 Investor’s Guide.” |